Flag of the United States

| |

| Other names | The Stars and Stripes, Old Glory |

|---|---|

| Use | National flag and ensign |

| Proportion | 10:19 |

| Adopted | June 14, 1777 (original 13-star version) July 4, 1960 (current 50-star version) |

| Design | Thirteen horizontal stripes alternating red and white; in the canton, 50 white stars on a blue field |

The flag of the United States of America consists of 13 equal horizontal stripes of red (top and bottom) alternating with white, with a blue rectangle in the canton bearing 50 small, white, five-pointed stars arranged in nine offset horizontal rows of six stars (top and bottom) alternating with rows of five stars. The 50 stars on the flag represent the 50 U.S. states and the 13 stripes represent the original Thirteen Colonies that rebelled against the British Crown and became the first states in the Union.[1] Nicknames for the flag include the Stars and Stripes, Old Glory,[2] and the Star-Spangled Banner (also the name of the country's official national anthem).

Because of its symbolism, the starred blue canton is called the "union". This part of the national flag can stand alone as a maritime flag called the Union Jack.[3]

Symbolism

The flag of the United States is one of the nation's widely recognized and used symbols. Within the U.S. it is frequently displayed, not only on public buildings, but on private residences, as well as iconically in forms such as decals for car windows, and clothing ornaments such as badges and lapel pins. Throughout the world it is used in public discourse to refer to the U.S., both as a nation state, government, and set of policies, but also as an ideology and set of ideas.

Many understand the flag to represent the national government established in the U.S. Constitution, the rights of the citizens promised in the Bill of Rights, and perhaps most of all to be a symbol of individual and personal liberty as set forth in the Declaration of Independence. The flag is a complex and contentious symbol, around which emotions run high.

Apart from the numbers of stars and stripes representing the number of current and original states, respectively, and the union with its stars representing a constellation, there is no legally defined symbolism to the colors and shapes on the flag. However, folk theories and traditions abound; for example, that the stripes refer to rays of sunlight and that the stars refer to the heavens, the highest place that a person could aim to reach.[4] Tradition holds that George Washington proclaimed: "We take the stars from Heaven, the red from our mother country, separating it by white stripes, thus showing that we have separated from her, and the white stripes shall go down to posterity representing Liberty."[5]

Design

Specifications

The basic design of the current flag is specified by 4 U.S.C. § 1; 4 U.S.C. § 2 outlines the addition of new stars to represent new states. The specification gives the following values:

- Hoist (width) of the flag: A = 1.0

- Fly (length) of the flag: B = 1.9[6]

- Hoist (width) of the Union: C = 0.5385 (A x 7/13, spanning seven stripes)

- Fly (length) of the Union: D = 0.76 (B × 2/5, two fifths of the flag length)

- E = F = 0.0538 (C/10, One tenth the height of the field of stars)

- G = H = 0.0633 (D/12, One twelfth the width of the field of stars)

- Diameter of star: K = 0.0616

- Width of stripe: L = 0.0769 (A/13, One thirteenth of the flag width)

These specifications are contained in an executive order which, strictly speaking, governs only flags made for or by the U.S. federal government.[7] In practice, however, virtually all U.S. national flags adhere to these specifications, or close to them.

Colors

The exact shades of red, white, and blue to be used in the flag are specified as follows:[8]

| Color | Cable color | Pantone[9] | Web Color[10] | RGB Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dark Red | 70180 | 193 C | #BF0A30

|

(191,10,48) |

| White | 70001 | Safe | #FFFFFF

|

(255,255,255) |

| Navy Blue | 70075 | 281 C | #002868

|

(0,40,104) |

The 49- and 50-star unions

When Alaska and Hawaii were being considered for statehood in the 1950s, more than 1,500 designs were spontaneously submitted to President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Although some of them were 49-star versions, the vast majority were 50-star proposals. At least three, and probably more, of these designs were identical to the present design of the 50-star flag.[11] At the time, credit was given by the Executive Department to the United States Army Institute of Heraldry for the design.

Of these proposals, one created by 18-year old Robert G. Heft in 1958 as a school project has received the most publicity. His mother was a seamstress, but refused to do any of the work for him. He originally received a B- for the project. After discussing the grade with his teacher, it was agreed (somewhat jokingly) that if the flag was accepted by Congress, the grade would be reconsidered. Heft's flag design was chosen and adopted by presidential proclamation after Alaska and before Hawaii was admitted into the union in 1959. He got an A.[12]

Decoration

Traditionally, the flag may be decorated with golden fringe surrounding the perimeter of the flag as long as it does not deface the flag proper. Ceremonial displays of the flag, such as those in parades or on indoor posts, often use fringe to enhance the beauty of the flag. The first recorded use of fringe on a flag dates from 1835, and the Army used it officially in 1895. No specific law governs the legality of fringe, but a 1925 opinion of the attorney general addresses the use of fringe (and the number of stars) "...is at the discretion of the Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy..." as quoted from footnote in previous volumes of Title 4 of the United States Code law books and is a source for claims that such a flag is a military ensign not civilian. However, according to the Army Institute of Heraldry, which has official custody of the flag designs and makes any change ordered, there are no implications of symbolism in the use of fringe.[13] Several federal courts have upheld this conclusion.[14]

Display and use

The flag is customarily flown year-round at most public buildings, and it is not unusual to find private houses flying full-size flags. Some private use is year-round, but becomes widespread on civic holidays like Memorial Day, Veterans Day, Presidents' Day, Flag Day, and on Independence Day. On Memorial Day it is common to place small flags by war memorials and next to the graves of U.S. war veterans. Also on Memorial Day it is common to fly the flag at half staff in remembrance of those who lost their lives in war while fighting for the U.S..

Flag etiquette

The United States Flag Code outlines certain guidelines for the use, display, and disposal of the flag. For example, the flag should never be dipped to any person or thing, unless it is the ensign responding to a salute from a ship of a foreign nation. (This tradition may come from the 1908 Summer Olympics in London, where countries were asked to dip their flag to King Edward VII: the American flag bearer did not. Team captain Martin Sheridan is famously quoted as saying "this flag dips to no earthly king," though the true provenance of this quotation is unclear[15][16]). The flag should never be allowed to touch the ground and, if flown at night, must be illuminated. If the edges become tattered through wear, the flag should be repaired or replaced.When a flag is so tattered that can no longer serve as a symbol of the United States, it should be destroyed in a dignified manner, preferably by burning. The American Legion and other organizations regularly conduct dignified flag-burning ceremonies, often on Flag Day, June 14. It is a common myth that if a flag touches the ground or a flag that is soiled must be burned as well. While a flag that is currently touching the ground and a soiled flag are unfit for display, neither situation is permanent and thus the flag does not need to be burned if the unfit situation is remedied.[17]

Significantly, the Flag Code proscribes using the flag "for any advertising purpose" and also states that the flag "should not be embroidered, printed, or otherwise impressed on such articles as cushions, handkerchiefs, napkins, boxes, or anything intended to be discarded after temporary use".[18] Both of these prohibitions are widely flouted, almost always without comment.

Although the Flag Code is U.S. Federal law, there is no penalty for failure to comply with the Flag Code and it is not widely enforced—indeed, punitive enforcement would conflict with the First Amendment right to freedom of speech.[19] Passage of the proposed Flag Desecration Amendment would overrule legal precedent that has been established in this area.

Places of continuous display

By presidential proclamation, acts of Congress, and custom, American flags are displayed continuously at certain locations.

- Replicas of the Star Spangled Banner Flag (15 stars, 15 stripes) are flown at two sites in Baltimore, Maryland: Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine[20] and Flag House Square.[21]

- United States Marine Corps War Memorial (Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima), Arlington, Virginia[22]

- Lexington, Massachusetts Town Green[23]

- The White House, Washington, DC[24]

- Fifty U.S. Flags are displayed continuously at the Washington Monument, Washington, DC.[25]

- At United States Customs Service Ports of Entry that are continuously open.[26]

- By Congressional decree, a Civil War era flag (for the year 1863) flies above Pennsylvania Hall (Old Dorm) at Gettysburg College[citation needed]. This building, occupied by both sides at various points of the Battle of Gettysburg, served as a lookout and battlefield hospital.

- Grounds of the National Memorial Arch in Valley Forge NHP, Valley Forge, Pennsylvania[27]

- Mount Slover limestone quarry (Colton Liberty Flag), in Colton, California. First raised July 4, 1917.[28]

- Washington Camp Ground, part of the former Middlebrook encampment, Bridgewater, New Jersey, Thirteen Star Flag. (Act of Congress.[citation needed])

- By custom, at the Maryland home, birthplace, and grave of Francis Scott Key; at the Worcester, Massachusetts war memorial; at the plaza in Taos, New Mexico (since 1861); at the United States Capitol (since 1918); and at Mount Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood, South Dakota.

- At the ceremonial south pole as one of the 12 flags representing the signatory countries of the original Antarctic Treaty.

- The surface of the Moon, having been placed there by the astronauts of Apollo 11,[29] Apollo 12, Apollo 14, Apollo 15, Apollo 16, and Apollo 17.

Particular days for display

The flag should especially be displayed at full staff on the following days:

- January: 1 (New Year's Day) and 20 (Inauguration Day)

- February: 12 (Lincoln's birthday) and the third Monday (Presidents' Day, originally Washington's birthday)

- May: Third Saturday (Armed Forces Day) and last Monday (Memorial Day; half-staff until noon)

- June: 14 (Flag Day)

- July: 4 (Independence Day)

- September: First Monday (Labor Day) and 17 (Constitution Day)

- October: Second Monday (Columbus Day) and 27 (Navy Day)

- November: November 11 (Veterans Day) and fourth Thursday (Thanksgiving Day)

- and such other days as may be proclaimed by the President of the United States; the birthdays of states (date of admission); and on state holidays.

Display at half staff

The flag is displayed at half staff as a sign of respect or mourning. Nationwide, this action is proclaimed by the president; state-wide or territory-wide, the proclamation is made by the governor. In addition, there is no prohibition against municipal governments, private businesses or citizens flying the flag at half staff as a local sign of respect and mourning. President Dwight D. Eisenhower issued the first proclamation on March 1, 1954 standardizing the dates and time periods for flying the flag at half staff from all federal buildings, grounds, and naval vessels; other congressional resolutions and presidential proclamations ensued. However, they are only guidelines to all other entities: typically followed at state and local government facilities, and encouraged of private businesses and citizens.

To properly fly the flag at half staff, the protocol is to first hoist it briskly to full staff, then reverently (slowly) lower it to half staff. Similarly, when the flag is to be lowered from half staff, it should be first hoisted briskly to full staff, then lowered reverently to the base of the flagpole.

Federal guidelines state the flag should be flown at half staff at the following dates/times:

- May 15 - Peace Officers Memorial Day

- Last Monday in May - Memorial Day (until noon)

- July 27 - Korean War Veterans Day

- September 11 - Patriot Day[30]

- December 7 - Pearl Harbor Remembrance Day

- For 30 days - Death of a president or former president

- For 10 days - Death of a vice president, Supreme Court chief justice/retired chief justice, or speaker of the House of Representatives.

- From death until the day of interment - Supreme Court associate justice, member of the Cabinet, former vice president, president pro-tempore of the Senate, or the majority and minority leaders of the Senate and House of Representatives. Also for federal facilities within a state or territory, for the governor.

- On the day after the death - Senators, members of Congress, territorial delegates or the resident commissioner of the commonwealth of Puerto Rico

Folding for storage

Though not part of the official Flag Code, according to military custom flags should be folded into a triangular shape when not in use. (The Philippines, a former American territory, also has this custom for folding its flag.) To properly fold the flag:

- Begin by holding it waist-high with another person so that its surface is parallel to the ground.

- Fold the lower half of the stripe section lengthwise over the field of stars, holding the bottom and top edges securely.

- Fold the flag again lengthwise with the blue field on the outside.

- Make a rectangular fold then a triangular fold by bringing the striped corner of the folded edge to meet the open top edge of the flag. Starting the fold from the left side over to the right

- Turn the outer end point inward, parallel to the open edge, to form a second triangle.

- The triangular folding is continued until the entire length of the flag is folded in this manner (usually thirteen triangular folds, as shown at right). On the final fold, any remnant that does not neatly fold into a triangle (or in the case of exactly even folds, the last triangle) is tucked into the previous fold.

- When the flag is completely folded, only a triangular blue field of stars should be visible.

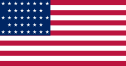

History

The flag has been changed 26 times since the new, 13-state union adopted it. The 48-star version went unchanged for 47 years, until the 50-star version became official on July 4, 1960 (the first July 4 following Hawaii's admission to the union on August 21, 1959); the 47-year-record of the 48-star version was the longest time the flag went unmodified until July 4, 2007, when the current 50-star version of the Flag of the United States broke the record.

First flag

At the time of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776, the United States had no official national flag. The Grand Union Flag has historically been referred to as the "First National Flag"; although it has never had any official status, it was used throughout the American Revolutionary War by George Washington and formed the basis for the design of the first official U.S. flag. The origins of the design are unclear. It closely resembles the British East India Company (BEIC) flag of the same era, and an argument dating to Sir Charles Fawcett in 1937 holds that the BEIC flag indeed inspired the design.[31] However, the BEIC flag could have from 9 to 13 stripes, and was not allowed to be flown outside the Indian Ocean.[32] Both flags could have been easily constructed by adding white stripes to a British Red Ensign, a common flag throughout Britain and its colonies.

Another theory holds that the red-and-white stripe—and later, stars-and-stripes—motif of the flag may have been based on the Washington family coat-of-arms, which consisted of a shield "argent, two bars gules, above, three mullets gules" (a white shield with two red bars below three red stars).[33]

More likely it was based on a flag of the Sons of Liberty, one of which consisted of 13 red and white alternating horizontal stripes.

The Flag Resolution of 1777

On June 14, 1777, the Marine Committee of the Second Continental Congress passed the Flag Resolution which stated: "Resolved, That the flag of the United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new Constellation."[34] Flag Day is now observed on June 14 of each year. A false tradition holds that the new flag was first hoisted in June 1777 by the Continental Army at the Middlebrook encampment.[35]

The 1777 resolution was probably meant to define a naval ensign, rather than a national flag. It appears between other resolutions from the Marine Committee. On May 10, 1779 Secretary of the Board of War Richard Peters, Jr. expressed concern "it is not yet settled what is the Standard of the United States."[36]

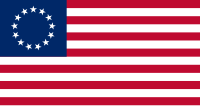

The Flag Resolution did not specify any particular arrangement, number of points, nor orientation for the stars. The pictured flag shows thirteen outwardly-oriented five-pointed stars arranged in a circle, the so-called Betsy Ross flag. Although the Betsy Ross legend is not taken seriously by many historians, the design itself is the oldest version of any U.S. flag to appear on any physical relic[citation needed], since it is historically referenced in contemporary battlefield paintings by John Trumbull and Charles Willson Peale, which depict the circular star arrangement. Popular designs at the time were varied and most were individually crafted rather than mass-produced. Other examples of 13-star arrangements can be found on the Francis Hopkinson flag, the Cowpens flag, and the Brandywine flag. Given the scant archaeological and written evidence, it is unknown which design was the most popular at that time.

Despite the 1777 resolution, a number of flags only loosely based on the prescribed design were used in the early years of American independence. One example may have been the Guilford Court House Flag, traditionally believed to have been carried by the American troops at the Battle of Guilford Court House in 1781.[37]

The origin of the stars and stripes design cannot be fully documented. A popular story credits Betsy Ross for sewing the first flag from a pencil sketch by George Washington who personally commissioned her for the job. However, no evidence for this theory exists beyond Ross' descendants' much later recollections of what she told her family. Another woman, Rebecca Young, has also been credited as having made the first flag by later generations of her family. Rebecca Young's daughter was Mary Pickersgill, who made the Star Spangled Banner Flag.

It is likely that Francis Hopkinson of New Jersey, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, designed the 1777 flag while he was the Chairman of the Continental Navy Board's Middle Department, sometime between his appointment to that position in November 1776 and the time that the flag resolution was adopted in June 1777. This contradicts the Betsy Ross legend, which suggests that she sewed the first Stars and Stripes flag by request of the government in the Spring of 1776.[34][38] Hopkinson was the only person to have made such a claim during his own lifetime, when he sent a bill to Congress for his work. He asked for a "Quarter Cask of the Public Wine" as payment initially. The payment was not made, however, because it was determined he had already received a salary as a member of Congress, and he was not the only person to have contributed to the design. It should be noted that no one else contested his claim at the time.

Later flag acts

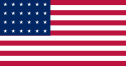

In 1795, the number of stars and stripes was increased from 13 to 15 (to reflect the entry of Vermont and Kentucky as states of the union). For a time the flag was not changed when subsequent states were admitted, probably because it was thought that this would cause too much clutter. It was the 15-star, 15-stripe flag that inspired Francis Scott Key to write "The Star-Spangled Banner," now the national anthem.

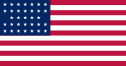

On April 4, 1818, a plan was passed by Congress at the suggestion of U.S. Naval Captain Samuel C. Reid[39] in which the flag was changed to have 20 stars, with a new star to be added when each new state was admitted, but the number of stripes would remain at thirteen to honor the original colonies. The act specified that new flag designs should become official on the first July 4 (Independence Day) following admission of one or more new states. The most recent change, from 49 stars to 50, occurred in 1960 when the present design was chosen, after Hawaii gained statehood in August 1959. Before that, the admission of Alaska in January 1959 prompted the debut of a short-lived 49-star flag.

As of July 4, 2007, the 50-star flag has become the longest rendition in use.

Historical progression of designs

In the following table depicting the 28 various designs of the United States flag, the star patterns for the flags are merely the usual patterns, often associated with the United States Navy. Canton designs, prior to the proclamation of the 48-star flag by President William Howard Taft on October 29, 1912, had no official arrangement of the stars. Furthermore, the exact colors of the flag were not standardized until 1934.[40]

| No. of Stars |

No. of Stripes |

Design | States Represented by New Stars |

Dates in Use | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 13 |  |

N/A | December 3, 1775[41]–June 14, 1777 | 1 year (18 months) |

| 13 | 13 |  |

Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maryland, South Carolina, New Hampshire, Virginia, New York, North Carolina, Rhode Island |

June 14, 1777–May 1, 1795 | 18 years (215 months) |

| 15 | 15 |  |

Kentucky, Vermont | May 1, 1795–July 3, 1818 | 23 years (278 months) |

| 20 | 13 |  |

Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi, Ohio, Tennessee |

July 4, 1818–July 3, 1819 | 1 year (12 months) |

| 21 | 13 |  |

Illinois | July 4, 1819–July 3, 1820 | 1 year (12 months) |

| 23 | 13 |  |

Alabama, Maine | July 4, 1820–July 3, 1822 | 2 years (24 months) |

| 24 | 13 |  |

Missouri | July 4, 1822–July 3, 1836 | 14 years (168 months) |

| 25 | 13 |  |

Arkansas | July 4, 1836–July 3, 1837 | 1 year (12 months) |

| 26 | 13 |  |

Michigan | July 4, 1837–July 3, 1845 | 8 years (96 months) |

| 27 | 13 |  |

Florida | July 4, 1845–July 3, 1846 | 1 year (12 months) |

| 28 | 13 |  |

Texas | July 4, 1846–July 3, 1847 | 1 year (12 months) |

| 29 | 13 |  |

Iowa | July 4, 1847–July 3, 1848 | 1 year (12 months) |

| 30 | 13 |  |

Wisconsin | July 4, 1848–July 3, 1851 | 3 years (36 months) |

| 31 | 13 |  |

California | July 4, 1851–July 3, 1858 | 7 years (84 months) |

| 32 | 13 |  |

Minnesota | July 4, 1858–July 3, 1859 | 1 year (12 months) |

| 33 | 13 |  |

Oregon | July 4, 1859–July 3, 1861 | 2 years (24 months) |

| 34 | 13 |  |

Kansas | July 4, 1861–July 3, 1863 | 2 years (24 months) |

| 35 | 13 |  |

West Virginia | July 4, 1863–July 3, 1865 | 2 years (24 months) |

| 36 | 13 |  |

Nevada | July 4, 1865–July 3, 1867 | 2 years (24 months) |

| 37 | 13 |  |

Nebraska | July 4, 1867–July 3, 1877 | 10 years (120 months) |

| 38 | 13 |  |

Colorado | July 4, 1877–July 3, 1890 | 13 years (156 months) |

| 43 | 13 |  |

Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Washington |

July 4, 1890–July 3, 1891 | 1 year (12 months) |

| 44 | 13 |  |

Wyoming | July 4, 1891–July 3, 1896 | 5 years (60 months) |

| 45 | 13 |  |

Utah | July 4, 1896–July 3, 1908 | 12 years (144 months) |

| 46 | 13 |  |

Oklahoma | July 4, 1908–July 3, 1912 | 4 years (48 months) |

| 48 | 13 |  |

Arizona, New Mexico | July 4, 1912–July 3, 1959 | 47 years (564 months) |

| 49 | 13 |  |

Alaska | July 4, 1959–July 3, 1960 | 1 year (12 months) |

| 50 | 13 |  |

Hawaii | July 4, 1960–present | 63 years (766 months) |

Future of the flag

The United States Army Institute of Heraldry has plans for flags with up to 56 stars, using a similar staggered star arrangement should additional states accede. There are political movements supporting statehood in Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia, among other areas.

Template:Begin flag gallery Template:Flag entry Template:End flag gallery

Similar national flags

Template:Begin flag gallery Template:Flag entry Template:Flag entry Template:Flag entry Template:Flag entry Template:End flag gallery

The flag of Liberia bears a close resemblance, showing the ex-American-slave origin of the country. The Liberian flag has similar red and white stripes, though only 11 of them, as well as a blue square for the union, but with only a single large white star.

The flag of Malaysia also has a striking resemblance, with red and white stripes (14 total), and a blue canton, but displaying instead of stars a star and crescent emblem. This might be due, however, to the great influence of the British East India Company, rather than the later United States flag.

The Flag of Chile resembles a simplified U.S. (or Liberian) flag, with just one star and two stripes.

The flag of Hawaii, in use since it was a kingdom in the 19th century, with eight stripes in red, white, and blue, and the British Union Flag in the canton, has some resemblance to the U.S. Grand Union Flag of the 18th century.

Reverse side flag

The U.S. flag cloth replica is worn on the right sleeve of uniforms such that the star field is to the observer’s right, as if the flag is flying in the breeze as the wearer moves forward.

See also

- Ensign of the United States

- Flags of the United States

- Flags of the U.S. states

- Flags of the United States armed forces

- Flags of the Confederate States of America

- Gallery of flags of United States cities

- Jack of the United States

- Old Glory

- Gadsden flag

- Nationalism in the United States

- Flag Code

- Hoa Kỳ

Article sections

Associated persons

- Francis Bellamy (1855–1931), creator of the Pledge of Allegiance

- William Driver (1803–1886), who owned and named "Old Glory"

- Charles Fawcett, British historian who suggested the design is based on the flag of the British East India Company

- Thomas E. Franklin (1966–), photographer of Ground Zero Spirit, better known as Raising the Flag at Ground Zero

- Christopher Gadsden (1724–1805), after whom the Gadsden flag is named

- Robert G. Heft (1941–), a designer of the current flag's canton

- Francis Hopkinson (1737–1791), designer (according to some historians)

- Jasper Johns (1930–), painter of Flag (1954–55), inspired by a dream of the flag

- John Paul Jones (1747–1792), who claimed to have first raised the Grand Union Flag aboard the Alfred in 1775

- Francis Scott Key (1779–1843), writer of "The Star-Spangled Banner"

- Mary Young Pickersgill (1776–1857), maker of the banner hoisted over Fort McHenry during the Battle of Baltimore

- Katha Pollitt (1949–), author of a controversial essay on post-9/11 America and her refusal to fly an American flag

- George H. Preble (1816–1885), author of History of the American Flag (1872) and photographer of the Fort McHenry flag

- Joe Rosenthal (1911–2006), photographer of Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima

- Betsy Ross (1752–1836), creator of the first stars and stripes flag (according to legend)

- George Washington (1732–1799), who (according to legend) first sketched the stars and stripes design and on whose family arms the design may be based

References

- Allentown Art Museum. The American Flag in the Art of Our Country. Allentown Art Museum, 1976.

- Herbert Ridgeway Collins. Threads of History: Americana Recorded on Cloth 1775 to the Present. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1979.

- Grace Rogers Cooper. Thirteen-star Flags: Keys to Identification. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1973.

- David D. Crouthers. Flags of American History. Hammond, 1978.

- Louise Lawrence Devine. The Story of Our Flag. Rand McNally, 1960.

- William Rea Furlong, Byron McCandless, and Harold D. Langley. So Proudly We Hail: The History of the United States Flag. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1981.

- Scot M. Guenter, The American Flag, 1777-1924: Cultural Shifts from Creation to Codification. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. 1990. online

- Marc Leepson, Flag: An American Biography. Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin's Press, 2005.

- David Roger Manwaring. Render Unto Caesar: The Flag-Salute Controversy. University of Chicago Press, 1962.

- Boleslaw Mastai and Marie-Louise D'Otrange Mastai. The Stars and the Stripes: The American Flag as Art and as History from the Birth of the Republic to the Present. Knopf, 1973.

- Milo Milton Quaife. The Flag of the United States. 1942.

- Milo Milton Quaife, Melvin J. Weig, and Roy Applebaum. The History of the United States Flag, from the Revolution to the Present, Including a Guide to Its Use and Display. Harper, 1961.

- Albert M. Rosenblatt. "Flag Desecration Statutes: History and Analysis," Washington University Law Quarterly 1972: 193-237.

- Leonard A. Stevens. Salute! The Case of The Bible vs. The Flag. Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1973.

Notes

- ^ States are represented collectively; there is no meaning to particular stars nor stripes.

- ^ Coined by Captain William Driver, a nineteenth century shipmaster.

- ^ No relation to the Union Flag of the United Kingdom to which this term more commonly refers.

- ^ "What do the colors of the Flag mean?". USFlag.org: A website dedicated to the Flag of the United States of America. Retrieved 2005-06-14.

- ^ "The United States Flag - Public and Intergovernmental Affairs". United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ Note that the flag ratio (B/A in the diagram) is not absolutely fixed. Although the diagram in Executive Order 10834 gives a ratio of 1.9, earlier in the order is a list of flag sizes authorized for executive agencies. This list permits eleven specific flag sizes (specified by height and width) for such agencies: 20.00 × 38.00; 10.00 × 19.00; 8.95 × 17.00; 7.00 × 11.00; 5.00 × 9.50; 4.33 × 5.50; 3.50 × 6.65; 3.00 × 4.00; 3.00 × 5.70; 2.37 × 4.50; and 1.32 × 2.50. Eight of these sizes conform to the 1.9 ratio, within a small rounding error (less than 0.01). However, three of the authorized sizes vary significantly: 1.57 (for 7.00 × 11.00), 1.27 (for 4.33 × 5.50) and 1.33 (for 3.00 × 4.00).

- ^ Ex. Ord. No. 10834, August 21, 1959, 24 F.R. 6865 (governing flags "manufactured or purchased for the use of executive agencies", Section 22).

- ^ According to Flags of the World, the colors are specified by the General Services Administration "Federal Specification, Flag, National, United States of America and Flag, Union Jack," DDD-F-416E, dated November 27, 1981. It gives the colors by reference to "Standard Color Cards of America" maintained by The Color Association of the United States, Inc.

- ^ The Pantone color equivalents for Old Glory Blue and Red are listed on U.S. Flag Facts at the U.S. Embassy's London site.

- ^ The RGB color values are taken from the Pantone Color Finder at Pantone.com.

- ^ These designs are in the Eisenhower Presidential Archives in Abilene, Kansas. Only a small fraction of them have ever been published.

- ^ "Robert G. Heft: Designer of America's Current National Flag". USFlag.org: A website dedicated to the Flag of the United States of America. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ "Fringe on the American Flag". Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ^ See McCann v. Greenway, 542 F.Supp. 647 (U.S. Dist. Ct. W.D. MO, 1997) which discusses various court opinions denying any significance related to trim used on a flag.

- ^ http://www.la84foundation.org/SportsLibrary/JOH/JOHv7n3/JOHv7n3i.pdf

- ^ London Olympics 1908 & 1948

- ^ Snopes.com: Flag Disposal retrieved June 14, 2008

- ^ 4 U.S.Code Sec. 8(i).

- ^ Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989); United States v. Eichman, 496 U.S. 310 (1990).

- ^ Presidential Proclamation No. 2795, July 2, 1948

- ^ Public Law 83-319, approved March 26, 1954

- ^ Presidential Proclamation No. 3418, June 12, 1961

- ^ Public Law 89-335, approved November 8, 1965

- ^ Presidential Proclamation No. 4000, September 4, 1970

- ^ Presidential Proclamation No. 4064, July 6, 1971, effective July 4, 1971

- ^ Presidential Proclamation No. 4131, May 5, 1972

- ^ Public Law 94-53, approved July 4, 1975

- ^ By Act of Congress. [1][dead link]

- ^ It is possible that Apollo 11's flag was knocked down by the exhaust force of liftoff for return to lunar orbit.[citation needed]

- ^ Patriot Day, 2005

- ^ The STRIPED FLAG of the EAST INDIA COMPANY, and its CONNEXION with the AMERICAN "STARS and STRIPES" at Flags of the World

- ^ East India Company (United Kingdom) at Flags of the World

- ^ A 2002 BBC documentary featuring the town of Selby and Selby Abbey showed the coat of arms with the comentator referring to it as the inspiration for the U.S. Flag, a commonly held belief in Britain.

- ^ a b Federal Citizen Information Center: The History of the Stars and Stripes. Accessed June 7, 2008.

- ^ Guenter (1990)

- ^ Mastai, 60

- ^ Other evidence suggests it dates only to the nineteenth century. The original flag is at the North Carolina Historical Museum.

- ^ Embassy of the United States of America [2] Accessed April 11, 2008.

- ^ United States Government (1861). Our Flag (PDF). Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office. S. Doc 105-013.

- ^ (For alternate versions of the flag of the United States, see the Stars of the U.S. Flag page at the Flags of the World website.)

- ^ Leepson, Marc. (2005). Flag: An American Biography. New York: St. Martin's Press.

External links

- United States at Flags of the World

- The Thirteen Stars and Stripes-A Survey of 18th Century Images of the US Flag

- U.S. Flag Etiquette (ushistory.org)

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding the flag

- Encyclopedia Smithsonian: Facts About the United States Flag (citation needs to be updated)

- The Flag Code—U.S. Code Home: Title 4, Flag and Seal, Seat of Government, and the States—Chapter 1, The Flag

- Provides details about the design of the flag, treatment of the flag, the pledge of allegiance, etc.

- Executive Order No. 10798, with specifications and regulations for the current flag

- Flag of the United States of America

- Civil Air Patrol - Flag Folding (YouTube) (Video on the proper folding of the United States flag)