Daniil Charms

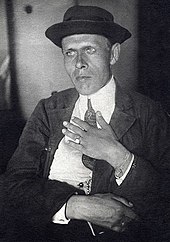

Daniil Kharms ( Russian Даниил Хармс ; actually Daniil Ivanovich Juwatschow , Даниил Иванович Ювачёв , scientific. Transliteration Daniil Ivanovich Juvačëv * 17 . Jul / thirtieth December 1905 greg. In St. Petersburg , Russian Empire , † 2. February 1942 in Leningrad , Soviet Union ) was a Russian writer and poet . His texts could only be printed in the course of perestroika and thus become known to a wider public. The literary estate includes all literary genres , his work is assigned to the avant-garde . Charms took part in the talks of the Tschinari and was a co-founder of the artists' association OBERIU (Eng. "Association of Real Art").

He is one of those writers whose work is difficult to understand without knowing the circumstances of his life. Charms' friend, the mathematician and philosopher Yakov Druskin , rescued the estate after his arrest by the NKVD from the bombed apartment in the besieged Leningrad and kept it for posterity.

Life

Family, school and university attendance

Daniil Iwanowitsch Juwatschow was born on July 17th . / December 30, 1905 greg. born in Saint Petersburg. His mother, Nadezhda Ivanovna Koljubakina (1869-1929), came from a long-established noble family from the Saratov governorate . From 1900 to 1918 she headed a women's asylum for released prisoners in St. Petersburg. His father, Iwan Juwatschow (1860-1940), was the seventh child of a family of parquet polishers in the Anitschkow Palace . He was arrested as a member of the anti-Tsarist Narodnaya Volya in 1883 and sentenced with other officers in 1884. The death penalty was commuted to 15 years imprisonment, 12 of which he served as slave labor on Sakhalin . After the early pardon in 1895, he was allowed to return to St. Petersburg four years later. Under the pseudonym Miroljubow (Eng. "The peace-loving") he published numerous writings until the end of the 1920s.

Koljubakina and Juwachev met in St. Petersburg in 1902 and married on April 16, 1903. The first-born son died at the age of one month, which was a great burden for the mother, as she told her husband in a letter. A year later, Daniil was born, who grew up with his sister Yelisaveta, who was born in 1909. Another daughter of the family died in 1920 at the age of eight.

In the first fourteen years of their marriage, Juwachev traveled a lot as an auditor for the state savings banks. During this time, the couple wrote each other many letters, from whose maternal enclosures for the father the oldest Charms manuscripts come. The mother's letters give an insight into the child's development. The father devoted himself to his son with educational advice that corresponded to his strict and ascetic way of life . The Russian Orthodox upbringing of the parents began at an early age . The mother taught two-year-old Daniil to make the sign of the cross and bow. The father, who had been converted into a devout Christian after years of imprisonment, also devoted himself to religious education. Reading the Bible was firmly anchored in everyday life. In Charms' private notes and work, religious symbolism and occupation with occult topics play an important role.

Everyday correspondence at home shaped Charms' turn to writing and writing at an early age. He learned to read at the age of five and knew entire stories by heart; According to his mother, he wrote flawlessly at the age of six. The parents encouraged the children's linguistic development by employing English and German-speaking teachers and enabling them to attend the prestigious German-speaking St. Petri School . In 1915 Charms started first grade, where he learned English as well as German. In 1922, however, he had to leave school prematurely because of poor grades and inappropriate behavior. He then attended the Second Soviet Union Workers School in the Petersburg suburb of Detskoye Selo , where he graduated from college on July 14, 1924.

Charms then took up his studies at the electrical engineering center in Leningrad, which he dropped out after a year. He did not finish the studies he began in 1926 at the film department of the Institute for Art History in Leningrad, headed by Boris Eichenbaum . His entries in the diaries, however, testify to his serious interest in the content of the course. Here he met the two directors Leonid Trauberg and Grigori Kosinzew , who belonged to the experimental theater group FEKS, which had a strong influence on his work. The trivialized avant-gardism, the game with absurdity and the banalized exaggeration of the everyday are seen as similarities.

In the spring of his first year of study, Charms met Ester Alexandrovna Rusakowa, whose marriage ended in divorce in 1927. Rusakowa and Charms were married on March 5, 1928 and had a spirited marriage until their divorce in 1933. During this time 1928–1932 Charms was friends with the painter and illustrator Alisa Poret , who did not illustrate his poems and stories (until 1980). In August 1933 Charms met Marina Malitsch, whom he married on July 16, 1934. The two lived - as was typical in the former Soviet Union - in a communal apartment (" Kommunalka ") with Charms' parents and his sister's family. Like other Russian writers, for example Joseph Brodsky , Charms used scenes from life in the Kommunalka in his work.

From Juwachev to Charms

Charms signed his texts with various pseudonyms : "Chcharms", "Chorms", "Protoplast", "Iwanowitsch Dukon-Charms", "Garmonius" or "Satotschnik". However, he did not change his first name. His most common - "Charms" - was entered in the passport as an artist name. The meaning is not clearly clarified. Borrowings from French charme (German “magic”), English charm (German “magic”) or English harm (German “damage”, “unhappiness”), but also a sound borrowing from the name of his German teacher Jelisaweta Harmsen as well as Sherlock Holmes (Russian "Scherlok Cholms") admired by Charms could have played a role. He signed his oldest surviving poem from 1922 with “D. Ch. ”And is therefore regarded as the oldest evidence for the pseudonym“ Charms ”. In the children's magazines and books he used "Kolpakow", "Karl Iwanowitsch Schusterling" and others.

Charms cultivated a style of clothing that was unusual for the time and was associated with Sherlock Holmes. This slope is already described for the 18-year-old by a classmate: Charms wore beige-brown clothes, a checked jacket, shirt and tie, golf trousers. A small pipe in the mouth.

However, close people urge a differentiated point of view. Jakow Druskin emphasizes that many researchers reduce charms to the two-year phase of OBERIU, the extravagant clothing style and the staging of theatrical performances. Marina Malitsch, Charms' wife, has a similar point of view: “People who say that Danja wore a fool's mask are not entirely wrong, I think. Probably this mask actually determined his behavior. Although I have to say: the mask appeared very natural, it was easy to get used to. ”Peter Urban, who was the first to translate Charms into German, visited the writer Nikolai Khardschiew (1903–1996) in Moscow in 1972 , the manuscripts of Possessed charms. When Urban wanted to know how Charms endured living with the prospect of never being able to publish a line, the whole answer from Khardjiev, who was crying, was: “Charms was not made for this world. He was too fragile, too delicate ”.

Cultural, social and political milieu

As an adult, Daniil Charms experienced the upheaval between the tsarist past and the Soviet future. When he was born in the revolutionary year of 1905 , St. Petersburg had been the capital for two centuries and the scene of all major revolutions until 1918. The famine that began after the October Revolution and the civil war caused the population to fall from 2.5 million to 722,000 in 1920. The Juwachev family also left the city and spent some time in the house of their maternal grandparents in the Saratov area.

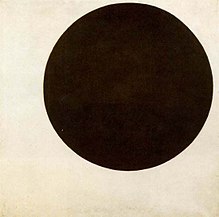

With the upheaval, the Silver Age ended with its main literary currents, symbolism , acmeism and futurism . The heterogeneous, provocative direction of Futurism played particularly with the roots of words and sound elements of the language and was a model for Charms. In painting, futurism was expressed in abstract art , the most important representative of which in St. Petersburg was Kazimir Malevich (" Cubofuturism ").

In 1925 Charms met the poet Alexander Vwedenski , who had been friends with the philosopher Leonid Lipawski and Jakow Druskin since they were at school . Charms found a connection with this group, with whom he maintained a close friendship across all groups throughout his life. In his diaries Druskin names names and titles that shaped him and his friends. These include the philosophers Nikolai Losski and Vladimir Solovyov , the poets and futurists Velimir Chlebnikow , Alexei Kruchonych and the early Mayakovsky, as well as the films The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari or Dr. Mabuse, the player . Gustav Meyrink , Knut Hamsun and especially the works of Sigmund Freud are named as influential writers , of which 28 of the 50 Russian translations were published by the Staatsverlag alone until the ban in 1936. In the 1920s, the psychoanalytic movement in the Soviet Union reached its peak and also employed other representatives of the avant-garde.

Artistic circles and first arrest

Charms was not only in different, different artistic groups, he also cultivated various other contacts, which can be tapped by name through his systematically kept records. These included around 150 writers, more than 60 actors and directors and around 50 painters.

1925 Charms met the poet and art historian Alexander Tufanow , who with his seal of Velimir Khlebnikov anknüpfte, for its phonemic was known experiments and was among the last who wrote in the zaum'-According to tradition. The first writers' association that Charms joined was the Order DSO founded by Tufanow . In autumn 1925 they renamed themselves Samovtschina and then in Left Flank .

Together with Vwedensky, Charms formed the Tschinari (Eng. "Rank", "Official") association in 1926 , a private circle of friends in which the two philosophers Druskin and Lipawski play an important role and which dealt primarily with religious issues. The minutes of the talks from 1933 and 1934 have been preserved.

Charms was also a member of official associations. On March 26, 1926, he was accepted into the All-Russian Poets Association, from which, however, he was excluded again on September 30, 1929 due to unpaid membership fees. On July 1, 1934, he joined the Writers' Union of the USSR, which was founded in 1932 .

In 1927, together with Vvedensky and Nikolai Sabolozki, he founded the artists' association OBERIU (Eng. "Association of Real Art"), which in its manifesto called for the authorization of different art movements - literature, visual arts, theater and film - side by side. The first public event, Three Left Hours, took place on January 24, 1928 in the Haus der Presse. During the first hour, which was under the motto Art is a cupboard , the Oberiuts crawled, walked or sat on a black lacquered cupboard. Charms' play Jelisaveta Bam was premiered in the theater lesson . The self-made anti-war silent film The Meat Grinder was shown in the third hour accompanied by live jazz music.

In April 1930 OBERIU was declared hostile to the state and banned by the political leadership following criticism of the communist newspaper.

Charms probably had his last appearance in front of a larger public at the funeral service for Malevich, when he read his poem Auf die Tod Kasimir Malewitsch in his apartment on May 17, 1935 . Later appearances only took place in front of children and young people.

He saw only two of his poems printed for adults: 1926 Incident on the Railway (Russian "Slučaj na železnoj doroge") in the Lyrical Manac of the All-Russian Poets Association , and 1927 Poem by Pyotr Jaschkin (Russian "Stitch Pjotra Jaškina") in an anthology of Leningrad Poets Union. His prose works , plays and poems were known only to a few close people. Planned book publications failed. For example, in August 1928 he put together an anthology that was to appear in Paris (“ Tamisdat ”). The anthology, Archimedes' Tub, planned together with other Leningrad authors in the spring of 1929 , could not appear either.

Charms was first arrested on December 10, 1931. The same fate befell Tufanov, Vvedensky, Bakhterev and other writers. The next day, Charms stated:

“I work in the field of literature. I am not a politically thinking person, but the question that is close to me is: literature. I declare that I do not agree with the policy of the Soviet government in the field of literature and, as a counterbalance to the existing measures on this point, I wish the freedom of the press, both for my own work and for the literary work of writers close to me who form my own literary group with me. "

In the spring of 1932 he was sentenced to three years' exile in Kursk with Vvedensky for “participating in an anti-Soviet illegal association of writers” . His father obtained early release in Leningrad on November 18, 1932.

However, the Russian poet and essayist Olga Martynova also recalls the everyday life that poets experience in a totalitarian state. Not only would there be house searches and arrests, but also the feeling

“To not belong, to be poor, to be badly dressed, to live in a poor ambience, to appear to others, who have better adaptability, as a strange owl. You have to be very resilient to turn away from general aesthetics and create an autonomous world in a tiny circle. "

Writer and reciter for children

Children's book and magazine culture developed in the Soviet Union from the mid-1920s. The Leningrad Department for Children's Literature of the State Publishing House has been headed since 1925 by Samuil Marschak together with Nikolai Oleinikow and Yevgeny Schwarz . Along with Kornei Tschukowski, Marschak is considered a classic of Soviet children's literature. With Maxim Gorki's backing, he was able to maintain a certain degree of independence until the mid-1930s. From 1928 the magazine Josch (Eng. "Igel") was published for older children and from 1930 the magazine Tschisch (Eng. "Zeisig") was published for younger children . Both magazines had a playful, artistic and intellectual wealth in their early years, which the Oberiuts were to shape.

After the event three hours left , Marschak offered the Oberiuts to cooperate. Although Charms had never written for children, Marschak saw opportunities for children's literature to be implemented in the language games and sometimes mystical content of his adult literature. He understood that everything that was criticized about the Oberiuts - the bridle lyric, excessive attention to form, word creations, etc. a. - would be an advantage in children's literature. At that time it was not unusual for authors to write for adults as well as for children, as in St. Petersburg, for example, Ossip Mandelstam , Boris Pasternak , Nikolai Tichonow , Viktor Shklowski and Michail Slonimski .

In the following years, numerous texts by Charms appeared in Josch , Tschisch and as independent book publications, establishing his reputation as a writer for children. As early as 1928, the first year of his collaboration, his poem Iwan Iwanowitsch Samovar and the three stories The Journey to Brazil or How Kolja Pankin Flew to Brazil and Petya Erhov did not want to believe him , first and second, and The Old Woman Who Wanted to Buy Ink printed in the Josch ; In addition, four children's books with a size of one to two sheets of paper appeared in mass editions. In the years that followed, it was not uncommon for books of the same name to appear as independent publications after being reprinted in Josch or Tschisch , such as the story First and Second illustrated by Vladimir Tatlin or the volume of poetry Iwan Iwanowitsch Samovar illustrated by Wera Yermolajewa . These books reached up to 20 editions during Charms' lifetime. In January 1934 he invented the character of the clever Mascha for the Tschisch , who had to endure adventure. Very popular with the children, she received many letters and calls. His last children's book, Fuchs und Hase , came out in 1940 and the last stories were printed in Tschisch in the spring of 1941 .

His children's poems have a nonsense character and the anecdotal poems are reminiscent of his adult literature, but he also wrote philosophical poems and used word and sentence games in his stories.

But Charms not only appeared in print, but also at recitations in clubs or pioneer palaces. The children's enthusiasm is described by some contemporary witnesses in their memories:

“The children were not fooled by Charms' sinister appearance. Not only were they very fond of him, he literally enchanted them. I've seen and heard Charms perform a lot. And always the same. The hall is noisy. Daniil Charms comes on stage and mumbles something. Little by little the children become silent. Charms still speaks softly and darkly. The children burst out laughing. Then they fall silent - what does he say? [...] Then he could do what he wanted with the children - they looked breathlessly at his mouth, completely caught up in the play on words, the magic of his poems, by himself. "

It is said that he couldn't stand children and was even proud of them. Private correspondence shows that he spoke unconventionally about children. With this apparent discrepancy, however, the attraction of his texts was also explained: "The offer of communication [...] insists on its seriousness by making it difficult and emphasizing the distance between the points of view."

Second arrest and death

At the height of the Great Terror in 1937, Charms was again politically attacked. This time because of a poem in Tschisch in which a person leaves the house, disappears and does not return. The diary entry from June 1st illustrates his perception of the situation:

“An even more terrible time has come for me. In the Detizdat [Ger. 'Verlag für Kinderliteratur'] they have stumbled upon some of my poems and are starting to suppress me. I am no longer being printed. They don't pay me the money and justify that with some random delay. I feel something secret, evil is going on there. We don't have anything to eat. We are terribly hungry. "

The following year he couldn't publish anything. It is not clear whether Charms actually wanted to evoke associations with arrested people, which would have been quite dangerous. His wife brings a different reading into play, since Charms suggested to her at the time that she just go away and hide in the woods.

But not only was the economic situation threatening, his social structure also changed radically: on July 3, Nikolai Oleinikov was arrested and shot on November 24, 1937; Banishment of Oleinikov's wife; the editor responsible for Josch died in the camp, the editorial secretary of the children's book publisher spent 17 years in the camp; On August 6, further arrests of employees of the children's book publisher, some of whom were murdered, such as the physicist Matwei Bronstein ; On August 28, the family of Charms' first wife was arrested: Ester was killed in the camp in 1938, her four siblings were sentenced to 10 years in the camp; On September 5, Marschak's editorial office was broken up and Marschak fled; On September 14th, the former editorial secretary des Josch was arrested .

On October 23, 1937, Charms wrote in his diary:

"My God, I have only one request from you: destroy me, smash me for good, push me to hell, don't let me stand halfway, but take my hope and destroy me quickly, forever."

And a week later: “I'm only interested in the 'nonsense', which has no practical meaning. I am only interested in life in its nonsensical appearance. "

Two months after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Charms was arrested for the second time on August 23, 1941. This time he was accused of spreading defeatist propaganda. In the forensic medical report from the same day it says: “He is able to orientate himself. He has fixed ideas, the perception is reduced. He has strange ideas. ”The diagnosis is“ Psychosis (schizophrenia?) ”. In further interrogations, Charms denied having committed crimes against the Soviet Union. On September 2, he was transferred to the neighboring prison psychiatry and again declared insane on September 10. This finding is based on the report from autumn 1939, when Charms simulated schizophrenia in order to be exempted from service in the Soviet-Finnish war . Charms should have been released, but on November 26, 1941 an NKVD agent incriminated him severely. The indictment on December 7th read:

“On the basis of the results of the psychiatric examination of 10.IX.1941, the defendant Juvačëv-Charms is declared insane and insane in the guilt he is charged with. [... He] has to go to a psychiatric hospital for forced healing until he is fully recovered . "

In mid-December, Charms was admitted to the psychiatric institution of the Leningrad Kresty Prison . Unaware of his whereabouts, his wife was only able to visit him in February 1942. When she registered, she received the information: "Died on February 2nd." The alleged cause of death during the Leningrad blockade is malnutrition . The place of death and burial are unknown.

History of transmission and publication

1941 to 1988: The art is in the closet

Charms' records remained in the Kommunalka after his wife left. In September a bomb destroyed part of the house, whereupon Druskin and Charms' wife gathered all the manuscripts in October and brought them to his apartment. When Druskin learned of Charms' death, which he initially did not want to believe, he wrote in his diary on February 10, 1942: “Lately DI has been talking about the victim. If his death is a sacrifice, it is too great. Now it obliges. "

In June 1942 he was evacuated to the Urals , took the manuscripts with him, and after his return to liberated Leningrad in 1944, he hid them - besides those of Charms also those of Vvedensky and Nikolai Oleinikov - in a cupboard under a pile of old books, out of fear Persecution, but for the first 15 years also in the hope that those arrested will return.

In the 1960s he began to show the manuscripts to the literary scholar Michail Meilach , whom he had met through his brother, and Anatoly Alexandrow, whose copies spread underground (" samizdat "). The American Slavist George Gibian wanted to have them printed abroad, which Druskin refused, because he hoped for a possibility of publication in his own country. Nevertheless, an English-language volume published by Gibian appeared in 1971 and one in Russian three years later in Würzburg. Dissatisfied with the result, Druskin finally agreed to a publication abroad. From 1978 to 1980 the first three volumes of the first Russian-language work edition, edited by Meilach and Wladimir Erl, were published in Bremen . Meilach, who lives in Leningrad, had to spend four years in the Perm 36 labor camp because of this editorial work . After his early release during perestroika, he published the fourth volume in Bremen in 1988 - at the same time as the first Soviet edition of Alexandrow.

Shortly before his death in 1978, Druskin left the original manuscripts to public institutions: children's literature from the Pushkin House and adult literature from the National Library in Leningrad, but not the private records such as diaries or letters. Other smaller texts were also privately owned by others. In the early 1990s, some poems, letters, and diary notes that were believed to be lost appeared in the OGPU files of the 1931 arrest.

Second Russian avant-garde

Charms' fate resembles that of many writers in the Soviet Union, whose literature was divided into a domestic literature, which was suppressed to different degrees, and a free foreign literature. The de-Stalinization brought about a cultural thaw in the late 1950s , which ended in 1964 with Nikita Khrushchev's fall. In the same year in which Alexander Solzhenitsyn published the novel A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich , the writer and children's book author Lidija Tschukowskaja received the new edition of Charms' children's book Igra. Stichi dlja detej ( Eng . "Game. Poems for Children"). In 1967 came the anthology Čto eto bylo? (Eng. "What was that?") out. Many of his poems and stories were also printed as individual contributions and thus made him known to a further generation of children. In 1967, the Literaturnaja Gazeta published Charms' anecdotes about Pushkin . In the same year, Yuri Lotman invited Alexandrow and Meilach to present poems at a student philological conference in Tartu , which were well received by the Slavists.

In the public eye, Charms remained a humorous writer for children until the late 1980s. In the private sphere, on the other hand, a second Russian avant-garde was formed, with copies of the banned authors spreading. One of the leading representatives, Moscow's Vsevolod Nekrasov , recalls:

“The handwritten or typewritten poems by Pasternak , Zwetajewas , Charms or Mandelstam were actually still occasionally kept with one or the other in storage boxes together with cereal grains in the mid-1950s. Is that weird or horrible? […] But in the event that something of the legacy was discovered, the poems could frighten you with a sudden knock on the door, entangle you in conversations and drive you to informants - that also happened. In a word, with such fearful relation to the manuscript, there was nothing to laugh about. "

In Moscow, among other things, a. from Ilya Kabakov Charms' texts. The conceptual artist Viktor Piwowarow , whose writing and drawing was influenced by Charms', describes the atmosphere in the early 1970s:

“One of these relatively large copies of poems, short stories and the Elizaveta Bam had been given to Kabakov by someone and we read it out loud with enthusiasm. In general, those were years of Charms, the feeling of the happy, gloomy absurdity was in the air. "

In 1977, an elaborate samizdat tape was made by the Moscow Valery Abramkin , whose text was comparatively good thanks to Alexandrov.

Flight to Heaven from 1988?

The perestroika allowed in 1988 the first edition of Charms' work on Soviet soil, entitled Flight in the sky appeared. At first it was not possible to spread it more widely, as the economic situation only permitted small editions. In addition, the decades of scattered storage of the manuscripts of the persecuted Oberiuts made collective publications very difficult. For Meilach, publishing private records that Charms would never have consented to went too far. He sharply criticized the "primitive Freudian interpretations" that some letters and diary entries evoked. Between 1994 and 2010 editions with texts by the Oberiuts appeared without those of Vwedenski, because Vladimir Glozer , the son of his second wife, secured the copyright and demanded large sums of money. The son from the second marriage of Charms' wife, however, brought a copyright lawsuit before a German court: In a judgment of September 2011, the distribution of Urban's translations, which were published in the Friedenauer Presse , was prohibited due to the revival of copyright law. The question of copyright is judged controversially: While Meilach describes Glozer as addicted to litigation, Alexander Nitzberg sees him as the guarantor of copyrights in the midst of “countless pirated prints and commercial exploitation”.

Charms only wrote by hand . His estate consists of over thirty notebooks, notebooks and countless individual sheets of various origins: calendars, telegram forms and other forms of all kinds, such as bureaucratic and propaganda materials, cemetery forms or invoices. Charms has not thrown anything away, so texts in the drafting stage have been preserved as well as completed versions. Since he arranged very few text cycles such as the cases , the editors have to compile the texts.

Spelling deviating from spelling, for which it is not always clear whether or not they are intended, was handled differently in the Russian editions: Michail Meilach and Alexander Kobrinski corrected spelling mistakes that they considered to be unintentional and pointed them out in the text-critical apparatus , while Vladimir Glozer and Valery Sashin wanted to reproduce the texts precisely, which they did not always succeed. This practice led to sometimes heated discussions among the editors about how to properly use the original manuscripts.

plant

Charms' texts are different from anything printed back then. His literary legacy includes most literary genres : prose, poetry, plays, anecdotes, fairy tales, dialogues, short and brief stories as well as diary entries, letters and drawings. The brevity of his texts is characteristic, the longest reaching the length of a short story. A poetological reorientation is consistently observed in literary studies from 1932 onwards, which is explained by the experience of banishment and the prohibition to perform. In a more recent study, his early work is also divided into word and sound-oriented poetry and theatrical poetry.

Sound and word-oriented poetry of the 1920s

In this phase Charms turned developed by Khlebnikov and Kruchenykh techniques of destruction of the word meaning by neologisms and incorrect sentence structures to. Based on a futuristic artificial language, it is also called the bridle phase . Charms' work contained bridle elements until about 1930, after which he wrote only a few bridle poems. In the zaum'-lyric, familiar semantic contexts are simulated and then resolved, for example in Who are we on Wu (Russian: "S kem my na ky") instead of Who are we on you . Word and sound properties therefore play an important role. The invention of magic words and formulas such as foken, poken, zoken, moken is also typical of charms .

An untitled poem in the form of a nursery rhyme from October 1929 shows the destruction of everyday life by saying "nothing":

|

|

In the original version, the last stanza with the terms "theater", "magazines" and "art" described cultural rather than social decay.

Theatricalized poetry (from 1926 to 1932)

In the so-called OBERIU phase or Oberiut phase, Charms devoted himself to the theater. It began around 1926 - when he started his studies in the film department - and lasted until 1932. In his text Objects and Figures (Russian: “Predmety i figuri”) Charms deals with the object and human consciousness. Accordingly, every object has a graphic meaning, a purpose, a meaning of the emotional and a meaning of the aesthetic impact on people. The fifth meaning is the free will of the object. Charms introduces the cupboard as an example: "The fifth meaning of the cupboard - is the cupboard." With this description of the object as a tension between relative and absolute beings, Charms anticipates the central statements of the Oberiuts' manifesto.

Characteristic of his poems is the largely unreal and incomprehensible world of images, thoughts, objects and concepts as well as their accumulated dialogical structure, the theatricalization of his writing is recognizable in the dialogized poems.

The play The Comedy of the City of St. Petersburg (1927), like the play Jelisaveta Bam (December 1927), does not reveal any plot. In Elizaveta Bam , the protagonist, whose name is onomatopoeic think of a death knell leaves and with saying bambuwskoe poloschenie is associated, accused of murder, arrested by their murder victims and asked why they did not kill it (dt "predicament."):

|

|

Prose (1932 to 1941)

The work from 1932 onwards, in which he increasingly devoted himself to prose, is referred to as the post-Oberiutic phase or Charms' phase . Since he was no longer allowed to appear in public, communication with the recipients fell away. Private and artistic life are closely intertwined, genre boundaries between his everyday notes and his artistic work are becoming increasingly blurred. His texts are characterized by a more restrained thought poetry in which he takes a stand on his positions. The fragmentary character of the poetry diminishes and the focus on themes increases. Subjects of the prose are:

- 1931: metaphysical-religious search: prayer before sleep (Russian "Molitva pered snom")

- 1935: Hunger and Death: Terrible Death (Russian "Strašnaja smert '")

- 1937: Loss of freedom and threat from violence: I cannot think fluently (Russian: "Ja plavno dumat 'ne mogu")

- 1939: physical and psychological crippling of people: the old woman (Russian "Starucha")

The longest prose piece the length of a short story is Die Alte . Charms wrote the last two stories on June 9 and 10, 1941: Symphony No. 2 and Rehabilitation .

The best known are the cases that have continuities with his slapstick theater. Urban emphasizes that in the cycle compiled in autumn 1939, the interplay of genres is the actual principle of order: poetry, short and brief stories, dramatic dialogue and anecdotes stand side by side on an equal footing. The eponymous text of the cases was written on August 22, 1936:

|

|

Texts from this phase force their readers in greatly reduced everyday scenes to accept the disappearance of people, death, food and receipt of mail equally. The Slavist and literary scholar Wolfgang Kasack sees a description of the early Soviet period in the texts, despite the high degree of abstraction:

"He grasped being at the mercy, the degradation of the material and the de-soul of existence through the creation of a fictional world of automatically functioning, mutually alienated characters, depersonalized (and thus also not preserving their individuality) human larvae."

The absurd moment is often that the lyrics usually have no punch line.

Druskin believes three moments are essential to understanding Charms' work. "The formal absurdity, the alogical nature of the situations in his texts as well as the humor were a means of exposing life, a means of expressing the real absurdity" Charms always said, according to Druskin, that there are two sublime things in life, humor and holiness . For Charms, holiness was real life - living life. With his humor he exposed the fake, frozen, already dead life, the dead shell of life, the impersonal existence. Another moment was his interest in evil without judging it morally. In his terrible stories he laughs at it by exposing evil, narrow-mindedness and dullness.

Another group of texts can be traced back to the conversations of the Tschinary, whose discourse Charms partly alienates, partly imitates. The question of the seriousness of these philosophical-scientific investigations cannot always be answered unequivocally: "Overall, it is [...] not so much a question of the scientification of art, [...] as more of an artificialization of science."

drawings

Charms drew a lot. As early as the six-year-old, his mother reported that he was designing cars and water pipes with great concentration. The oldest surviving drawings are a cycle of seven pictures with German titles depicting the creation myth, which were made in the summer after returning from the Saratov governorate. They show not only the talent for drawing, but also the early maturity of the thirteen year old.

Dissemination, reception and interpretation

With the first English-language publication, the scientific analysis of the Oberiut texts and thus also of Charms' texts in the USA began in the 1970s. The selection of the published texts determined the image of charms. The concept of the absurd as a paraphrase of OBERIU was coined by Gibian's publication Russia's Lost Literature of the Absurd in 1971. In the following period OBERIU was in the Western research with the Theater of the Absurd by Martin Esslin equated, although plays account for only a small portion of their texts. For the same reason, Charms' prose pieces have been associated with Samuel Beckett and Franz Kafka . A more recent examination of the Oberiut texts, however, with reference to earlier statements, emphasizes that the religious and spiritual background is important for the interpretation. The context of contemporary history, on the other hand, is brought to the fore by those who see Charms' texts as an image of absurd Stalinism. It was criticized that this reading would be similar to the NKVD, which had also seen subversive messages everywhere .

Charms' work has been translated into most languages, including Romanian, Hebrew, Serbo-Croatian, and Japanese.

The play Jelisaweta Bam was performed for the first time in the FRG in 1983 in the West Berlin Künstlerhaus Bethanien at the Berliner Festspielwochen and received positive reviews. The first major positive response received a montage of Charms' stories, draft letters, dialogues and other fragments from the Zan Pollo Theater in Berlin, which received reviews such as “sensational theater work” or “theater event of the season”. In the 1990s, his plays were shown on German stages an average of two times a year.

The first dissertation on OBERIU appeared in the Soviet Union in 1988, and since then Charm's work has been the subject of various questions, including a habilitation thesis from 2006 on the philosophical and aesthetic foundations of his work. The first monograph was published in French in 1991 and in Russian in 1995 in Russia.

Druskin believes that a knowledge of life is essential to understanding the work of Charms. Urban therefore linked the texts with concrete political events for the first time in 1992 and shows with the dialogue Is there anything on earth that would have meaning (Russian "Est 'li čto-nibud' na zemle ...") that this is with the knowledge of the arrest Charms' friend Oleinikov read it differently 13 days earlier.

Besides Konstantin Waginow , Charms was most often translated into German by the Oberiuts, but mostly prose. In the FRG, the distribution of his works is closely linked to Peter Urban . The writer and translator discovered the name in a Czech literary newspaper in 1967, and in 1968 he published some prose pieces in the Kursbuch magazine . In 1970 he published an anthology based on samizdat texts with Charms' works. The first English-language anthology appeared in 1971 in the USA, the first in Russian in 1974 in Germany. The first Russian-language edition of the work was published in Germany from 1978 to 1988; the first extensive German-language edition from 1984 in a translation by Urban is based on it. In the GDR, some of Charms' fairy tales were first published as children's books in 1982 and a selection of his texts for adults in 1983. Valery Sashin published the first largely complete Russian-language complete edition in Russia from 1997 to 2002. The four-volume German-language work edition, which was published in 2010 and 2011 by Galiani-Verlag and translated by Alexander Nitzberg , among others , is based on it.

Culture of remembrance

Charms has not yet been legally rehabilitated. Although his sister succeeded in overturning the 1941 sentence in 1960, when the Moscow film studio made a documentary about Charms in 1989 and investigated the exact circumstances of his death, the KGB press department issued a statement to the film team that stated that the 1960 rehabilitation was invalid, because Charms “as a mentally ill person should not have been charged with the incriminated act”. Since there was no criminal offense, there was also no need for rehabilitation.

In May 1990 the OBERIU and Theater conference took place in Leningrad . In 2005, on the initiative of the Dmitri Likhachev Fund and the St. Petersburg Cultural Committee, a commemorative plaque was placed on the house in which he lived between 1925 and 1941 on the occasion of Charms' 100th birthday . Her text "A person went out of the house" is intended to remind of Charms' arrest in the courtyard. In the same year, an international scientific conference took place in St. Petersburg from June 24th to 26th, 2005, which ended with an international charms festival.

Kasack closes his portrait of Daniil Charms with the words:

“The fact that Charms' work in Russia and abroad was only accessible long after he was assassinated by the state is tragic, but the positive assessment and influence of his works decades after their creation prove the validity of this poetry bought through so much suffering. "

Selection of publications (posthumous)

Russian-language editions

- George Gibian (Ed.): Izbrannoe. Jal. Würzburg 1974, ISBN 3-7778-0115-1 .

- Michail Mejlach, Vladimir Erl '(Ed.): Sobranie proizvedenij. Stichotvorenija 1926–1929. Komedija goroda Peterburga. K press. Bremen 1978.

- Michail Mejlach, Vladimir Erl '(Ed.): Sobranie proizvedenij. Stichotvorenija 1929–1930. K press. Bremen 1978.

- Michail Mejlach, Vladimir Erl '(Ed.): Sobranie proizvedenij. Stichotvorenija 1931–1933. Lapa. Gvidon. K press. Bremen 1980.

- Michail Mejlach, Vladimir Erl '(Ed.): Sobranie proizvedenij. Stichotvorenija 1933–1939. K press. Bremen 1988.

- Anatolij A. Aleksandrov (Ed.): Polet v nebesa. Stichi. Proza. Dramy. Pis'ma. Sovetsky Pisatel '. Moscow 1988, ISBN 5-265-00255-3 .

- Valerij N. Sažin (Ed.): Polnoe sobranie sočinenij. Stichotvorenija. Akademičeskij Proekt, St. Petersburg 1997, ISBN 5-7331-0032-X .

- Valerij N. Sažin (Ed.): Polnoe sobranie sočinenij. Proza i scenki, dramatičeskie proizvedenija. Akademičeskij Proekt, St. Petersburg 1997, ISBN 5-7331-0059-1 .

- Valerij N. Sažin (Ed.): Polnoe sobranie sočinenij. Proizvedenija dlja detej. Akademičeskij Proekt, St. Petersburg 1997, ISBN 5-7331-0060-5 .

- Valerij N. Sažin (Ed.): Polnoe sobranie sočinenij. Neizdannyj charms. Traktaty i stati, pis'ma, dopolnenija k t. 1-3. Akademičeskij Proekt, St. Petersburg 2001, ISBN 5-7331-0151-2 .

- Valerij N. Sažin (Ed.): Polnoe sobranie sočinenij. Zapisnye knižki. Dnevnik. Tom 1. Akademičeskij Proekt, St. Petersburg 2002, ISBN 5-7331-0166-0 .

- Valerij N. Sažin (Ed.): Polnoe sobranie sočinenij. Zapisnye knižki. Dnevnik. Tom 2. Akademičeskij Proekt, St. Petersburg 2002, ISBN 5-7331-0174-1 .

German-language editions

Translated by Peter Urban

- Cases. Prose, scenes, dialogues. Fischer , Frankfurt am Main 1970.

- Stories from Himmelkumov and other personalities. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-921592-17-8 .

- Cases. Scenes, poems, prose. Haffmans Verlag , Zurich 1984, ISBN 3-251-00051-9 .

- Falling. Prose, scenes, children's stories, letters. Haffmans Verlag , Zurich 1985, ISBN 3-251-00065-9

- Letters from Petersburg 1933. Friedenauer Presse , Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-921592-46-1 .

- Art is a cupboard, From the Notebooks 1924–1940. Friedenauer Presse , Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-921592-70-4 .

- Theatre! Almost all pieces. Publishing house of the authors , Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-88661-178-7 .

- Cases. Prose, scenes, dialogues. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-932109-26-0 . (significantly expanded edition from 1970)

- Sardam circus . Marionette play, Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-932109-27-9 .

- Archimedes' tub. Poems. Edition Korrespondenzen, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-902113-45-6 .

Translated by Ilse Tschörtner

- First and second. Fairy tale. Children's book publisher Berlin , 1982 (illustrations by Erich Gürtzig )

- Paradox. Verlag Volk und Welt , Berlin 1983. (Illustrations by Horst Hussel )

- Incidents. Luchterhand Collection, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-630-62049-3 . (German first edition: Verlag Volk und Welt, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-353-00605-2 . 1st paperback edition: Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1993. ISBN 3-596-11123-4 )

Translated by Alexander Nitzberg

- Strange Pages: Selected Poems and Stories for Children. bloomsbury K&J, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8270-5355-8 . (Translated with Andreas Tretner, illustrations by Vitali Konstantinov ).

- Charms Werk 02. Seven tenths of a head. Poems. Galiani, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86971-029-7 .

- Charms work 03. We cut nature in two. Plays. Galiani, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-86971-030-3 .

More translators

- Simply frills. Eto prosto erunda. (German-Russian), dtv, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-423-09326-9 . (Translated by Gisela and Michael Wachinger).

- First second. Carlsen , Hamburg 1996, ISBN 3-551-51456-9 . (Translated by Karel Alt).

- Cases. (Russian-German), Reclam, reprint, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-15-009344-9 . (Translated by Kay Borowsky ).

- Charms Werk 01. Drink vinegar, gentlemen. Prose. Galiani, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86971-025-9 . (Translated by Beate Rausch).

- Charms work 04. Autobiographical, letters, essays. Galiani, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-86971-031-0 . (Translated by Beate Rausch).

- Ulrike Damm (Ed.), Daniil Charms in Works by Contemporary German Artists, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-9815294-1-8

Audio books

- Cases (read by Peter Urban). Kein & Aber Records, Zurich 2003, ISBN 3-0369-1139-1 . (Translated by Peter Urban).

- Simply frills (read by Inga Busch, Hermann Lause, Tilo Prückner , Lou Hardt and many children). Patmos 2007, ISBN 978-3-491-24107-7 . (Translated by Gisela and Michael Wachinger).

- How terribly our strength is dwindling, translated from Russian by Peter Urban , read by Ueli Jäggi , Felix von Manteuffel , Peter Urban, André Jung and Fritz Zaugg ; Christoph Merian, Basel 2010 (1 CD), ISBN 978-3-85616-443-0 .

Radio plays

- 1991: The old woman - director: Ulrich Gerhardt (radio play - SFB / SDR )

Movies

Film adaptations of the work (Russian)

- 1984: Pljuch i Plich. Cartoon film Plisch und Plum by Wilhelm Busch , translation into Russian: Daniil Charms

- 1987: Slučaj Charmsa ( Eng . "The Charms Case"), surrealist drama, director: Slobodan Pešič

- 1989: Klounada ( Eng . "Clowning"), absurd tragic comedy, director: Dmitrij Frolov

- 1991: Staru-cha-rmsa ( Eng . "The Old Charms"), directed by Vadim Gems

- 1996: Koncert dlja krysy ( Eng . "Concert for a rat", colloquially also writer's soul), a political absurdity, director: Oleg Kovalov

- 1999: Upadanie ( Eng . " Dead laughing "), director: Nikolaj Kovalev

- 2007: Padenie v nebesa ( Eng . "Fall in Heaven"), directed by Natal'ja Mitrošnaja

- 2009: P'esa dlja mužčiny ( Eng . "A play for a man"), directed by Vladimir Mirzoev

- 2010: Charmonium (Eng. "Charmonium"), cartoon

- 2011: Slučaj s borodoj ( Eng . "Case with a beard"), directed by Evgenij Šiperov

About Charms (Russian)

- 1989: Strasti po Charmsu ( Eng . “Passions / Horrors à la Charms”), documentary film (television), director: L. Kostričkin

- 2006: Tri levych časa ( Eng . "Three Left Hours"), documentary film, director: Varvara Urizčenko

- 2008: Rukopisi ne gorjat… fil'm 2-y. Delo Daniila Charmsa i Aleksandra Vvedenskogo ( Eng . "Manuscripts don't burn ... Part 2. The case of Daniil Charms and Alexander Vvedenskij "), documentary film, director: Sergej Goloveckij

About Charms (German)

- 1996: Charms Incidents. Movie, director: Michael Kreihsl

- 2011: The old woman. Feature film, director: Ariane Mayer

Exhibition catalogs

- 2017: Encounters with Daniil Charms. Edited by Marlene Grau, Staats- u. Hamburg University Library (in cooperation with Van Abbemuseum Eindhoven), ISBN 978-90-79393-20-6 .

literature

To the biography

- Marina Durnowo: My life with Daniil Charms. Memories. Galiani, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86971-023-5 .

- Vladimir Glocer, Marina Durnovo: Moj muž Daniil Charms. IMA-Press, Moscow 2001, ISBN 5-901401-28-X .

- Aleksandr Kobrinsky: Daniil Charms. Molodaja gvardija. Moscow 2008, ISBN 978-5-235-03118-0 .

- Gudrun Lehmann: Falling and disappearing. Daniil Charms. Life and work. ( Arco Wissenschaft 20 special volume ) Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 .

- Peter Urban (Ed.): Art is a cupboard. From the notebooks 1924–1940. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-921592-70-4 . (Translation of private records. Data on life and work on pp. 279–332.)

To the work

- Thomas Grob: Daniil Charms' infantile childhood. A literary paradigm of the late avant-garde in the context of Russian modernism. Peter Lang, Bern et al. 1994, ISBN 3-906752-63-1 , ( Slavica Helvetica 45), (also: Zurich, Univ., Diss., 1993).

- Aleksandr Kobrinsky (editor): Stoletie Daniila Charmsa. Materialy meždunarodnoj naučnoj konferencii, posvjaščaennoj 100-letiju so dnja roždenija Daniila Charmsa. IPS SPGUTD, St. Petersburg 2005, ISBN 5-7937-0171-0 . (Eng .: "100 years of Daniil Charms. Materials of the international scientific conference, dedicated to the 100th anniversary of Daniil Charms' birthday.").

- Ljubomir Stoimenoff: Basics and procedures of the linguistic experiment in the early work of Daniil J. Charms. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1984, ISBN 3-8204-7434-X .

To OBERIU

- Aleksandr S. Kušner: Poety group "OBERIU". Sovetsky pisatel '. St. Petersburg 1994, ISBN 5-265-02520-0 .

- Graham Roberts: The last Soviet avant-garde. OBERIU - fact, fiction, metafiction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1997, ISBN 0-521-48283-6 .

- Lisanne Sauerwald: Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in the Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 .

- Special issue OBERIU of the magazine: Teatr. No. 11, 1991, ISSN 0131-6885 . (Especially about charms see pp. 10–79.)

Web links

- Literature by and about Daniil Charms in the catalog of the German National Library

- Poems, stories, biography, photos and drawings (German)

- Stories, poems, letters, diary entries (Russian)

- Photo gallery (labels in Russian) 1st row from left: father, aunt, 2 photos of children; 2-4 R .: Charms; 5th row: Charms at the arrest in 1941, Ester Rusakowa; Row 6: Marina Malitsch, 2 drawings by Charms'; 7th row: self-portraits; 8th row: various draftsmen

Individual evidence

- ↑ The unpublished letters, excerpts from the literature, can be found in the Tver State Archive "GATO", Fund Ivan Pavlovič Juvačov.

- ↑ Lisanne Sauerwald, Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in the Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 72.

- ↑ Cf. Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 28.

- ↑ Cf. Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 45.

- ↑ Cf. Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 45.

- ↑ Серафима ПОЛЯКОВА, научный сотрудник Музея изобразительных искусств РК: Алиса Порет и Даниил (accessed February 14, 2017.

- ↑ So the statement by Igor Bachterew quoted from Ljubomir Stoimenoff: Basics and procedures of the linguistic experiment in the early work of Daniil J. Charms. Peter Lang , Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1984, ISBN 3-8204-7434-X , p. 15. This is how he was called Juwachev-Charms in the indictment of December 7, 1941 .

- ↑ There are lists of pseudonyms in publications: For example Gudrun Lehmann: Fallen und Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 32 and the corresponding footnotes on p. 478, footnotes 73-76.

- ↑ Cf. Aleksandr Kobrinskij: Daniil Charms. Molodaja gvardija. Moscow 2008, ISBN 978-5-235-03118-0 , p. 490. The poem is called: V ijule kak-to v delo naše ( Eng . "In July somehow, in our summer").

- ↑ Photographs can be viewed here. The “Sherlock Holmes style” is evident on the hat and pipe. Accessed September 11, 2011.

- ↑ Aleksandr Kobrinsky: Daniil Charms. Molodaja gvardija. Moscow 2008, ISBN 978-5-235-03118-0 , p. 490.

- ↑ Explained in Jakov Druskin: Dnevniki. Gumanitarnoe Agentstvo Akademičeskij Proekt. St. Petersburg 1999, ISBN 5-7331-0149-0 , p. 508, footnote 48.

- ↑ Marina Durnowo: My life with Daniil Charms. Memories. Galiani, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86971-023-5 , p. 56. In the original, this passage reads: Ja dumaju, čto ne sovsem nepravy te, kto govorit, čto u nego byla maska čudaka. Skorej vsego ego povedenie dejstvitel'no opredeljalos' izbrannoj im maskoj, no, ja by skazala, očen 'estestvennoj, k kotoroj uže privykaeš' : Vladimir Glocer, Marina Durnovo: Moj muž Daniil Charms. IMA-Press, Moscow 2001, ISBN 5-901401-28-X , p. 75 f.

- ↑ Peter Urban (Ed.): Daniil Charms. Letters from St. Petersburg 1933. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-921592-46-1 , editorial note.

- ↑ Cf. Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 26.

- ↑ Marina Durnowo: My life with Daniil Charms. Memories. Galiani, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86971-023-5 , p. 50.

- ↑ Cf. Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 97.

- ↑ See Peter Urban (ed.): Art is a cupboard. From the notebooks 1924–1940. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-921592-70-4 , p. 284.

- ↑ Christfried Tögel: Lenin and Freud: On the early history of psychoanalysis in the Soviet Union. , Accessed on September 21, 2011.

- ↑ Brigitte Nölleke: History of Psychoanalysis in Russia , accessed on September 21, 2011.

- ↑ See Valerij Sažin: Daniil Charms sredi chudožnikov. In: Jurij S. Aleksandrov (ed.): Risunki Charmsa. St. Petersburg, Limbach 2006, ISBN 5-89059-079-0 , p. 284.

- ↑ Protocols ( Memento of December 7, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ With him, Vvedensky, Grigori Petnikow, Ossip Mandelstam and others were excluded. See Peter Urban (Ed.): Art is a cupboard. From the notebooks 1924–1940. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-921592-70-4 , p. 298.

- ↑ The ID is shown in the picture in: Marina Durnowo: My life with Daniil Charms. Memories. Galiani, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86971-023-5 .

- ↑ See Lisanne Sauerwald, Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 63.

- ↑ For a detailed description of the evening cf. Gudrun Lehmann: Falling and disappearing. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , pp. 183-198.

- ^ Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 179. The autograph is printed on p. 182.

- ↑ Published in Russian z. B. in: Aleksandr S. Kušner: Poety gruppy "OBERIU". Sovetskij Izdatel ', St. Petersburg 1994, ISBN 5-265-02520-0 , p. 235 f.

- ↑ Peter Urban (ed.): Art is a cupboard. From the notebooks 1924–1940. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-921592-70-4 , p. 303. The protocol is printed in Russian in: Aleksej Dmitrenko, Valerij Sažin (ed.): Sborišče druzej. Volume 2. Ladomir, Moscow 2000, ISBN 5-86218-265-9 , pp. 524 f.

- ↑ Olga Martynova: The source from which we drink. Discovery of the absurd - the Oberiuts are the liveliest of all Russian classics. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung of February 17, 2007, retrieved on March 28, 2019.

- ↑ Cf. Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 245.

- ↑ Cf. Gertraud Marinelli-König: Russian children's literature in the Soviet Union from 1920–1930. Otto Sagner, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-87690-987-5 , p. 46.

- ↑ Cf. Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 249.

- ↑ Cf. Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 249.

- ↑ Cf. Gertraud Marinelli-König: Russian children's literature in the Soviet Union from 1920–1930. Otto Sagner, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-87690-987-5 , p. 82.

- ↑ See Lisanne Sauerwald, Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 65 f.

- ↑ See Lisanne Sauerwald, Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 66.

- ↑ Cf. Aleksandr Kobrinskij: Daniil Charms. Molodaja gvardija. Moscow 2008, ISBN 978-5-235-03118-0 , p. 136 f.

- ↑ Cf. Aleksandr Kobrinskij: Daniil Charms. Molodaja gvardija. Moscow 2008, ISBN 978-5-235-03118-0 , p. 136.

- ↑ Cover of the Tschisch magazine with the “Klugen Mascha”, No. 2, 1935, accessed on September 17, 2011.

- ↑ Cf. the memoirs of the editor Nina Gernet (1904–1982) in Daniil Charms. Incidents. Luchterhand Collection, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-630-62049-3 , p. 354.

- ↑ Cf. Gertraud Marinelli-König: Russian children's literature in the Soviet Union from 1920–1930. Otto Sagner, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-87690-987-5 , p. 87.

- ^ So the memories of the children's book author Nina Gernet (1904–1982) translated by Lola Debüser in Daniil Charms. Incidents. Luchterhand Collection, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-630-62049-3 , p. 359. His wife expresses himself similarly in: Marina Durnowo: My life with Daniil Charms. Memories. Galiani, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86971-023-5 , p. 53 f. Thomas Grob quotes memories in Russian: Daniil Charms' infantile childhood. A literary paradigm of the late avant-garde in the context of Russian modernism. Lang, Bern et al. 1994, ISBN 3-906752-63-1 , p. 169, footnote 108.

- ↑ Marina Durnowo: My life with Daniil Charms. Memories. Galiani, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86971-023-5 , p. 54.

- ↑ The writer Jewgeni Schwarz is quoted in Thomas Grob: Daniil Charms' unkindliche Kindlichkeit. A literary paradigm of the late avant-garde in the context of Russian modernism. Lang, Bern et al. 1994, ISBN 3-906752-63-1 , p. 166.

- ↑ This is analyzed using a draft letter from Charms to his sister, in which he congratulated her son on his birthday in Thomas Grob: Daniil Charms' unkindliche Kindlichkeit. A literary paradigm of the late avant-garde in the context of Russian modernism. Lang, Bern et al. 1994, ISBN 3-906752-63-1 , p. 167.

- ↑ Thomas Grob: Daniil Charms' infantile childhood. A literary paradigm of the late avant-garde in the context of Russian modernism. Lang, Bern et al. 1994, ISBN 3-906752-63-1 , p. 169.

- ↑ Diary entry from June 1, 1937. Printed in: Peter Urban (Ed.): Art is a cupboard. From the notebooks 1924–1940. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-921592-70-4 , p. 216.

- ↑ Cf. Aleksandr Kobrinskij: Daniil Charms. Molodaja gvardija. Moscow 2008, ISBN 978-5-235-03118-0 , p. 381 f.

- ^ Dates and names of the victims in: Peter Urban (Ed.): The art is a cupboard. From the notebooks 1924–1940. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-921592-70-4 , pp. 321–326.

- ↑ Peter Urban (ed.): Art is a cupboard. From the notebooks 1924–1940. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-921592-70-4 , p. 227.

- ↑ Peter Urban (ed.): Art is a cupboard. From the notebooks 1924–1940. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-921592-70-4 , p. 227.

- ↑ The arrest warrant is printed from p. 592 with the minutes of the apartment search and the minutes of Charms' interrogation in: Aleksej Dmitrenko, Valerij Sažin (ed.): Sborišče druzej. Volume 2. Ladomir, Moscow 2000, ISBN 5-86218-265-9 .

- ^ Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 416.

- ^ Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 416.

- ^ Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 419.

- ↑ Marina Durnowo: My life with Daniil Charms. Memories. Galiani, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86971-023-5 , p. 87.

- ↑ During the arrest, hardly anything was confiscated because of the war and because it was not made for ideological reasons. Cf. Michail Mejlach: Vokrug Charmsa. In: Aleksandr Kobrinskij (editor): Stoletie Daniila Charmsa. Materialy meždunarodnoj naučnoj konferencii, posvjaščaennoj 100-letiju so dnja roždenija Daniila Charmsa. IPS SPGUTD, St. Petersburg 2005, ISBN 5-7937-0171-0 , p. 132.

- ↑ At the time cf. Jakov Druskin's diary entries: Dnevniki. Gumanitarnoe Agentstvo Akademičeskij Proekt. St. Petersburg 1999, ISBN 5-7331-0149-0 , p. 506, footnote 44.

- ↑ In the original: “V poslednee vremja DI govoril o žertve. Esli ego smert '- žertva, to sliškom bol'šaja. Sejčas ona objazyvaet. ”Jakov Druskin: Dnevniki. Gumanitarnoe Agentstvo Akademičeskij Proekt. St. Petersburg 1999, ISBN 5-7331-0149-0 , p. 132.

- ↑ See the diary entries of Jakov Druskin: Dnevniki. Gumanitarnoe Agentstvo Akademičeskij Proekt. St. Petersburg 1999, ISBN 5-7331-0149-0 , p. 506, footnote 44.

- ↑ See Michail Mejlach: Vokrug Charmsa. In: Aleksandr Kobrinskij (editor): Stoletie Daniila Charmsa. Materialy meždunarodnoj naučnoj konferencii, posvjaščaennoj 100-letiju so dnja roždenija Daniila Charmsa. IPS SPGUTD, St. Petersburg 2005, ISBN 5-7937-0171-0 , p. 133.

- ↑ Mejlach also published works by Ossip Mandelstam. Cf. Michail Mejlach: Devjat 'posmertnych anekdotov Daniila Charmsa. In: Teatr . No. 11, 1991, ISSN 0131-6885 , p. 77.

- ^ Crypto bequests from Charms' texts were among others. a. with Aleksandr Tufanow, Nikolai Khardschiew, Gennadij Gor and Vladimir Glocer. Gudrun Lehmann: Falling and disappearing. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 608., footnote 15.

- ↑ Peter Urban (ed.): Art is a cupboard. From the notebooks 1924–1940. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-921592-70-4 , p. 336.

- ↑ Cf. Aleksandr Kobrinskij: Daniil Charms. Molodaja gvardija. Moscow 2008, ISBN 978-5-235-03118-0 , p. 5. 1968 appeared in No. 8 of the literary magazine Novyj with the article Vosvraščenie Charmsa ( Eng . “Charms' return”) cf. Gertraud Marinelli-König: Russian children's literature in the Soviet Union from 1920–1930. Otto Sagner, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-87690-987-5 , p. 86.

- ↑ Anekdoty iz žizni Puškina. In: Literaturnaja Gazeta. 1967, no.47.

- ↑ An essay by Aleksandrov and Mejlach with the title: "Tvorčestvo Daniila Charmsa." In: Materialy XXII Naučnoj Studenčeskoj konferencii was published. Poetics. Istorija literatury. Lingvistika. Tartu, Tartuskij Gosudarstvennyj Universitet 1967, pp. 101-104.

- ↑ See Lisanne Sauerwald, Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 28, footnote 64.

- ↑ Cf. Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 458.

- ^ Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 427.

- ↑ Viktor Pivovarov: Vljublennyj agent. Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie. Moscow 2001, ISBN 5-86793-152-8 , p. 67 f.

- ^ Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 433.

- ↑ Cf. Aleksandr Nikitaev: Teatr. No. 11, 1991, ISSN 0131-6885 , p. 77.

- ↑ Anatolij A. Aleksandrov (Ed.): Polet v nebesa. Stichi. Proza. Dramy. Pis'ma. Sovetsky Pisatel '. Moscow 1988, ISBN 5-265-00255-3 .

- ↑ Michail Mejlach: Vokrug Charmsa. In: Aleksandr Kobrinskij (editor): Stoletie Daniila Charmsa. Materialy meždunarodnoj naučnoj konferencii, posvjaščaennoj 100-letiju so dnja roždenija Daniila Charmsa. IPS SPGUTD, St. Petersburg 2005, ISBN 5-7937-0171-0 , p. 134.

- ↑ After the death Glozers 2009 2010 published a comprehensive Russian-speaking Vvedensky output. Pervyj sbornik poeta Vvedenskogo vychodit posle 17 let “molčanija”. Accessed October 16, 2011.

- ↑ Quoted from the full text in Beck-Online . Judgment by the Cologne Higher Regional Court of 23 September 2011, Az. 6 U 66/11. Judgment of the first instance before the LG Cologne on December 22, 2010, Az. 28 O 716/07.

- ↑ See Michail Mejlach: Vokrug Charmsa. In: Aleksandr Kobrinskij (editor): Stoletie Daniila Charmsa. Materialy meždunarodnoj naučnoj konferencii, posvjaščaennoj 100-letiju so dnja roždenija Daniila Charmsa. IPS SPGUTD, St. Petersburg 2005, ISBN 5-7937-0171-0 , p. 142.

- ↑ Alexander Nitzberg in: Charms Werk 01. Drink vinegar, gentlemen. Prose. Galiani, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86971-025-9 , p. 258.

- ↑ See Michail Mejlach: Vokrug Charmsa. In: Aleksandr Kobrinskij (editor): Stoletie Daniila Charmsa. Materialy meždunarodnoj naučnoj konferencii, posvjaščaennoj 100-letiju so dnja roždenija Daniila Charmsa. IPS SPGUTD, St. Petersburg 2005, ISBN 5-7937-0171-0 , p. 134.

- ↑ See Lisanne Sauerwald, Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 30.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Kasack: Russian Authors in Individual Portraits. Reclam (Universal Library No. 9322), Ditzingen 1994, ISBN 3-15-009322-8 , p. 92.

- ↑ Cf. Ljubomir Stoimenoff: Basics and procedures of the linguistic experiment in the early work of Daniil J. Charms. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1984, ISBN 3-8204-7434-X , p. 124 and cf. Lisanne Sauerwald: Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in the Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 82.

- ↑ Cf. Lisanne Sauerwald: Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in the Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 74.

- ↑ Cf. Lisanne Sauerwald: Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in the Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 74.

- ↑ Cf. Lisanne Sauerwald: Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in the Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 75.

- ^ In the translation by Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 108.

- ↑ Cf. Lisanne Sauerwald: Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in the Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 75.

- ^ In the translation by Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 108.

- ↑ Cf. Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 506, footnote 37.

- ↑ Cf. Ljubomir Stoimenoff: Basics and procedures of the linguistic experiment in the early work of Daniil J. Charms. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1984, ISBN 3-8204-7434-X , p. 32.

- ↑ Cf. Ljubomir Stoimenoff: Basics and procedures of the linguistic experiment in the early work of Daniil J. Charms. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1984, ISBN 3-8204-7434-X , p. 33.

- ↑ Cf. Ljubomir Stoimenoff: Basics and procedures of the linguistic experiment in the early work of Daniil J. Charms. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1984, ISBN 3-8204-7434-X , p. 45 ff.

- ↑ See Lisanne Sauerwald, Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 80.

- ↑ Cf. Angela Martini-Wonde in Wolfgang Kasack (ed.): Major works of Russian literature. Individual presentations and interpretations. Kindler's New Literature Lexicon. Kindler , Munich 1997, ISBN 3-463-40312-9 , p. 477.

- ↑ In the translation by Peter Urban: Fallen. Prose. Scenes. Children's stories. Letters. Haffmans, Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-251-01153-7 , p. 16.

- ↑ This is shown using the example of a letter and The Case with Petrakov in: Lisanne Sauerwald, Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 82.

- ↑ Cf. Ljubomir Stoimenoff: Basics and procedures of the linguistic experiment in the early work of Daniil J. Charms. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1984, ISBN 3-8204-7434-X , p. 124 ff.

- ↑ Cf. Angela Martini-Wonde in Wolfgang Kasack (ed.): Major works of Russian literature. Individual presentations and interpretations. Kindler's New Literature Lexicon. Kindler , Munich 1997, ISBN 3-463-40312-9 , p. 476.

- ↑ See Peter Urban (ed.): Art is a cupboard. From the notebooks 1924–1940. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-921592-70-4 , p. 329.

- ↑ See Peter Urban (ed.): Art is a cupboard. From the notebooks 1924–1940. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-921592-70-4 , p. 337.

- ^ Translation by Ilse Tschörtner in: Incidents. Luchterhand Collection, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-630-62049-3 , p. 15.

- ^ Wolfgang Kasack: Russian authors in individual portraits. Reclam (Universal Library No. 9322), Ditzingen 1994, ISBN 3-15-009322-8 , p. 92.

- ↑ See Lisanne Sauerwald, Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 82.

- ↑ Peter Urban (ed.): Art is a cupboard. From the notebooks 1924–1940. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-921592-70-4 , p. 5 f.

- ↑ See Lisanne Sauerwald, Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 82 f.

- ↑ Lisanne Sauerwald, Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in the Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 83 f.

- ↑ Jurij S. Aleksandrov (ed.): Risunki Charmsa. St. Petersburg, Limbach 2006, ISBN 5-89059-079-0 .

- ↑ The drawings “Der Tag”, “Astronom” and “Das Wunder” can be viewed online here, accessed on September 9, 2011.

- ↑ Cf. Gudrun Lehmann: Fall and Disappearance. Daniil Charms. Life and work. Arco, Wuppertal et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938375-21-1 , p. 37.

- ↑ Cf. Ljubomir Stoimenoff: Basics and procedures of the linguistic experiment in the early work of Daniil J. Charms. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1984, ISBN 3-8204-7434-X , p. 20 and Lisanne Sauerwald, Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in the Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 13.

- ↑ With information on other authors who come to this conclusion cf. Lisanne Sauerwald: Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in the Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 393.

- ↑ Svetlana Lukanitschewa: Ostracized authors. Works by Marina Cvetaeva, Michail Bulgakow, Aleksandr Vvedenskij and Daniil Charms on the German stages of the 90s. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2003, ISBN 3-484-66040-6 , p. 129.

- ↑ Anna Gerasimova: Problema smešnogo v tvorčestve oberiutov. Moscow.

- ^ Jean-Philippe Jaccard: Daniil Harms et la fin de l'avant-garde russe. Herbert Lang, Bern 1991, ISBN 3-261-04400-4 .

- ^ Jean-Philippe Jaccard: Daniil Charms i konec russkogo avangarda. Akademičeskij Proekt, St. Petersburg 1995, ISBN 5-7331-0050-8 .

- ↑ Peter Urban (ed.): Art is a cupboard. From the notebooks 1924–1940. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-921592-70-4 , p. 5.

- ↑ See Peter Urban (ed.): Art is a cupboard. From the notebooks 1924–1940. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-921592-70-4 , p. 338.

- ↑ See Lisanne Sauerwald, Mystical-Hermetic Aspects in Art Thought of the Russian Poets of the Absurd. Ergon, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-89913-812-2 , p. 31.

- ↑ Leipzig Almanac , accessed on September 10, 2011.

- ↑ See article in ZEIT from October 19, 1984: Why, why am I the best? , Accessed October 17, 2011.

- ↑ Mikhail Mejlach: Devjat 'posmertnych anekdotov Daniila Charmsa. In: Teatr . No. 11, 1991, ISSN 0131-6885 , p. 77 f.

- ↑ Article on the page of the Likhachev Fund from December 22, 2005: Memorial'naja doska na dome Charmsa (German memorial plaque on the house of Charms). Accessed September 11, 2011.

- ^ Wolfgang Kasack: Russian authors in individual portraits. Reclam (Universal Library No. 9322), Ditzingen 1994, ISBN 3-15-009322-8 , p. 93.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Charms, Daniil |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Juwachev, Daniil Ivanovich (real name); Хармс, Даниил Иванович (Russian spelling); Ювачёв, Даниил Иванович (Russian spelling, maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 30, 1905 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Saint Petersburg , Russian Empire |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 2, 1942 |

| Place of death | Leningrad , Soviet Union |