Domestic chicken

| Domestic chicken | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Domestic fowl ( Gallus gallus domesticus ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Gallus gallus domesticus | ||||||||||||

| ( Gmelin , 1789) |

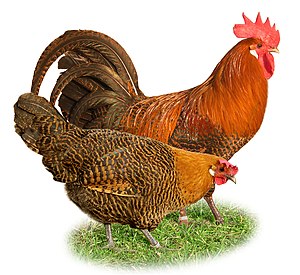

The domestic chicken ( Gallus gallus domesticus ), also briefly chicken (from Middle High German huon ), is a cultivated form of Bankivahuhns , a wild fowl from Southeast Asia, and belongs to the family of pheasant-like (Phasianidae). Agriculturally, they are poultry . The male domestic fowl called cock or rooster , castrated rooster capon . The female is called hen , young leading hens clucking hen . The young are generally called chicks .

The domestic chicken is considered to be man's most common domestic animal - the average daily world population is estimated at more than 20 billion animals, so there are three chickens for every person. The number of domestic chickens slaughtered annually is well above the average population and is estimated at 45 billion. This is due to the fact that chickens now reach their slaughter weight in just a few weeks. Due to the long history of domestication, a large number of different chicken breeds have emerged. In the European poultry standard alone, a distinction is made between over 180 breeds and colors. In industrial agriculture, hybrid chickens ( hybrid breeding of different pure- breeding inbred lines ) are used, which are not suitable for further breeding. Fattening and laying hybrids are bred and marketed by only four corporations worldwide.

External features

height and weight

The original chickens are relatively small compared to the usual domestic chicken breeds and lofts with a maximum weight of 1.5 kg for the roosters and 1.0 kg for the hens.

There is great variation in size and weight among domestic chickens. The smallest bantams (Serama) are partly with 250 g of the size of a small pigeon. The largest chickens (mostly hybrids), on the other hand, can weigh over 10 kg, comparable to a turkey. The largest chickens, the Brazilian giant chickens (Galo gigante), often grow to over 100 cm.

construction

The shape is also very different depending on the breed and breed. The slender, elongated shape of the primeval chicken is known as the country chicken type and is found in many European breeds. Many breeds of American and Chinese origin correspond to the so-called Cochin type with a heavier and spherical structure. Otherwise there are breeds with genetically very short or extremely long runs. The back line can rise slightly towards the rear or fall almost vertically.

Comb shape

The comb, which is always simple and fan-shaped in wild comb hens , has many variants. The rose comb is often seen, which is knobby and bulging and mostly ends in a thorn at the back. Certain races show a crest of horns with two fleshy horns. The cup comb in which two parallel combs at the front and back unite to form a cup is rare. The pea comb is very small; the missing comb also occurs.

Sexual dimorphism

The external difference between roosters and hens within a breed is striking. The comb is significantly larger in the rooster. The neck hangings consist of long feathers and the often sickle-shaped tail. Compared to the hen, the cock often has more color in its plumage. The rooster is larger and weighs about 1 kg more than the hen.

Runs

The barrel (actually the tarsometatarsus , also called the stand) and toes are mostly featherless. But there are breeds with foot feathering (some feathers up to longer feathers on the toes). Three toes are pointing forward, the fourth toe pointing back. Some breeds have five toes; H. two toes backwards ( polydactyly ). Adult roosters have a spur above the back toe (s) that serves as a weapon when attacked. This spur can become quite long and pointed in older animals. In a few old breeds of chicken, such as the Sumatra , roosters are predominantly multi-spurred.

behavior

Domestic chickens can fly a few meters differently depending on the breed, but they are ground-oriented birds. The domestic chicken was the first species of bird that was true to its location and was found to have a magnetic sense .

Vocalizations

The loud Kikeriki scream (the crowing ) of the rooster serves to mark the area acoustically. Usually the rooster crows in the morning at sunrise, around noon and towards evening. In ancient times, the cock's crow served as a time indication of Roman origin . Gallicinum denotes the middle between midnight and sunrise . He can also crow at any other time of the day. Crows competitions are still held today .

The cackling , the common utterance of all adult domestic chickens, is a relatively diverse communication tool that includes warning, threatening and luring calls.

See also: crow call , competition crows , long crows breed

food

In their natural habitat, chickens eat grass , grains , worms , snails , insects and even mice . Chickens are very vigilant when foraging for food and like to be in a dense landscape. They often scratch their feet on the ground to find something to eat. Gastroliths chop up hard food in your stomach . The picture of the brown hybrid hen shown here is an example of the beak docking that is practiced in the poultry industry to prevent cannibalism. However, this also makes it considerably more difficult to pick the food.

Laying behavior

Domestic chickens can lay around 250 to 300 eggs a year (laying breeds) if the egg is taken away from them every day. If the eggs were not removed, the hen would start incubating, provided that her brood instinct is sufficiently developed. In modern breeds, however, the breeding instinct was purposely bred away or greatly reduced. By changing the diet to exclusively wheat, the breeding instinct reappears in most cases. The breeding behavior is sometimes disturbed so that the hen does not finish incubating the eggs and leaves the nest prematurely. This misconduct is often shown by chickens that have hatched themselves in incubators . The incubation period is usually 21 days.

The earliest stages of gestation and blood circulation in the chicken embryo

Social behavior

The so-called pecking order of the chickens has become proverbial . Compared to the situation with other socially living animal species, however, this is quite flexible. Since chickens prefer to sleep as high as possible (free-range chickens sleep on trees at night), perches in stalls should be placed at the same height as possible in order to avoid constant battles for the best place to sleep. The grain forage is also spread over a wide area so that lower-ranking animals are not neglected. Regardless of the type of posture, issues such as feather pecking and even cannibalism can arise.

In the so-called battery of laying hens , social behavior is disturbed and the animals suffer, among other things. a. because of the lack of space for boredom and because they cannot satisfy their scratching instinct.

According to recent research, chickens have very pronounced social and communication behavior. Physiological measurements in hens indicate their empathy towards chicks. Also more remarkable intelligence skills have now been demonstrated, such as the logical solution of problems or tasks even under changing test conditions.

Life course

There are few reliable statements about the maximum age of the chicken. In specialist books, there are sometimes age specifications of up to 50 years. According to most reports, domestic chickens live to be around 5–7 years old (if not slaughtered beforehand), and in some cases 8–9 years old. Laying chickens usually die earlier than free-living chickens, which are not exposed to the stress of constant egg-laying. From the age of two, egg production decreases noticeably.

Diseases and parasites

In addition to avian influenza , mites , foot mange , pips and coligranulomatosis can occur. It can also lead to malformations such as abrachia - the lack of wings - which are inherited. Furthermore, coccidiosis , a diarrheal disease, and Marek , a paralysis, are common causes of death in chicks and young animals. A disease for which vaccination is compulsory in Germany is Newcastle disease . This disease, which is dangerous for animals of all ages, is transmitted by avian paramyxoviruses of serotype 1 and can lead to losses of up to 100%.

Chicken keeping and breeding

history

Molecular biological studies make it probable that the domestic chicken ( G. g. Domesticus ) originated from the Burmese bankiva chicken ( G. g. Gallus ), which is widespread in Southeast Asia . However, the history of domestication of the domestic chicken is more difficult to trace than that of larger domestic animals such as sheep or cattle. Chicken bones are preserved less often than the large mammals, they are more likely than these to end up in other archaeological layers and found bones are difficult to interpret, since both the wild form of the domestic chicken and francoline have very similar bones. Until the last quarter of the 20th century, most archaeologists did not bother to preserve these bones during excavations because it was believed that they would not provide essential information. This assessment has changed due to the prevailing belief that chicken bones can provide important keys about nutrition, social structure, trade routes and the state of the environment.

China

Bone finds in China indicate that as early as the 6th millennium BC A successful domestication took place. Chicken bones are found from a number of Middle Neolithic sites, such as Miaodigou ( Shanxian County , Henan ), Beishouling ( Baoji ) and Jiangzhai ( Lintong ). This would be very remarkable because it would have kept chickens there long before agriculture existed in the region. The uniqueness of these finds has therefore always been questioned. Among other things, it has been pointed out that it was not the age of the bones that was determined, but the layer in which they were found, which is considered problematic in the case of chicken bones. The oldest written references to chicken farming in China date from 1400 BC. Around the same time that the domestic chicken first appeared in ancient Egypt .

Indus culture and Egypt

Secure evidence of domestication in the Indus culture comes from the period from 2500 to 2100 BC. In Egypt, domestic chickens were around 1475 BC. Known: On the walls of the so-called Annal Hall in the Amun Temple in Karnak , the Thutmose III. (* around 1486 BC; † March 4, 1425 BC), there are inscriptions that tell of his campaigns. Also shown are the tribute payments of the subject countries and, according to the overwhelming opinion, four chickens are shown. In the grave ( TT100 ) of the ancient Egyptian vizier Rechmire from the same period there is also a vase, which is believed to be a Minoan tribute payment. On this vase there is a rough representation of a bird with a comb, two wattles and a pointed beak. It is believed to be the oldest known representation of a rooster. It is undisputed that a rooster is a depiction on a small limestone that Howard Carter found not far from the tomb of Tutankhamun and which dates back to 1300 BC. BC and 1100 BC Is dated.

Europe

In the Greek cultural area, chickens are not yet mentioned by Homer (approx. 800 BC), but they are already depicted relatively frequently on black-figure Greek vases; they were probably held mainly for cockfighting . They also served as marks on the shields of the warriors.

The Bucchero chicken from Viterbo was found in Italy , an Etruscan ceramic figure from the 7th century BC that served as a vessel. Chr.

The first finds in Central Europe come from the early Iron Age ( Hallstatt culture ) from the Heuneburg near Hundersingen. The chickens of that time were still able to fly, less true to their location than today's breeds and were kept in the barn all the time. Iron Age chicken remains are also known from Spain , where it was probably introduced by the Phoenicians . From the 5th / 4th Century BC Finds come from Switzerland ( Gelterkinden and Möhlin ).

However, the domestic chicken only found widespread use in Europe since the Romans , who raised chickens on a large scale as egg and meat suppliers. Columella's Guide to Agriculture contains a lot of advice on keeping chickens and mentions several breeds.

North and South America

According to general belief, it was only European settlers who introduced the domestic chicken to South and North America. The first documented imports took place in 1493, when Christopher Columbus also brought 200 chickens with him on his second trip to Hispaniola. In 2007, however, archaeologists found 88 chicken bones on the west coast of South America not far from the Chilean city of Arauco , which came from pre-Columbian times with the help of a radiocarbon dating method . The site was found in a village that was inhabited for over seven centuries until 1400 AD and whose settlement history ended before Columbus reached America. It is a generally accepted theory today that humans from East Asia settled the two American continents via Beringia . However, the Beringia land bridge only existed during the last ice age and thus long before a domestication of the grouse began, which extended its range beyond Southeast Asia. Skeptics of the dating of the find point out that the investigating laboratories may not have considered the find situation sufficiently and assessed the bones as too old.

If there were domestic chickens on the American continent before Columbus, then Japanese or Polynesian sailors, Vikings or Irish monks could be involved. Domestic chickens existed in Sweden as early as 500 AD, and chicken bones have been documented for Iceland that could be dated to the 13th century. However, there is no evidence of chickens in the settlements that Vikings established on the Atlantic coast of Newfoundland . Nor is there any evidence that indigenous peoples of North America raised domestic chickens before Columbus. The 1519 reports from Hernán Cortés to the King of Spain that the natives would sell chickens the size of peacocks in the markets refer to the turkey . Other reports refer in all probability to not more closely related to the domestic chicken cracidae that were half wild held in villages in the Amazon and. Independently of this, the domestic chicken quickly found widespread use in South America. As early as the end of the 16th century, it was common practice in what is now Bolivia, Peru and Mexico to pay taxes with chickens and eggs. This was also a result of settlers bringing chickens from Europe, Africa and Asia. For example, it is certain that chickens kept by the Bantu peoples of Africa reached what is now Brazil as early as 1575. DNA studies of chickens from South America make it at least possible that South America was the first to keep chickens from Polynesia, which were later crossed with chickens that reached South America across the Atlantic.

Modern times

The relative isolation of rural areas, which lasted until the 19th century, due to which there was little or no exchange of animals with other regions, led to the development of numerous land races. Interest in the development of breeding standards only began gradually in the 18th century, although individual breeds existed as early as the 16th century. The first breed shows were held in the early 19th century, but they didn't become popular events until the second half of the 19th century. The first breeding associations were founded during this period.

Queen Victoria , at least in Great Britain, contributed directly to the increasing interest in new chicken breeds or in improving the performance of old chicken breeds . In September 1842, Victoria and her Prince Consort Albert received five hens and two roosters from the British navigator and polar explorer Edward Belcher , who was returning from Asia.Their tame, compact physique, size and rich fletching are strikingly different from traditional British breeds such as the Dorking distinguished. Belcher's indications of the origin of his souvenir from Asia are contradictory. He called the small flock of chickens both Vietnamese Shanghai poultry and Cochin China poultry , but the chickens may actually have come from Malaysia.

Queen Victoria had a large aviary built for the chickens, appointed a keeper for them and began a very successful breeding program. As early as the following spring, the Belgian King Leopold received fertilized eggs from this " very rare and very interesting " breed of chicken, which is now known as the Cochin . The royal interest in this breed of chicken quickly caught the press. As early as 1844, the Berkshire Chronicle recommended the breed for crossbreeding with British land breeds, and a little later Queen Victoria had hens and roosters of her breed shown at agricultural exhibitions. In doing so, she possibly started an enthusiasm for exotic breeds of chickens, which was called " The Fancy " between 1845 and 1855 in both Great Britain and North America and, because of the exorbitant prices paid for exotic breed chickens, with the Dutch tulip mania in the second half of the 16th century.

Chicken breeds

definition

The term “breed” is used within the organized breeding of chickens (and other domestic animals) to denote a group of similar animals that are characterized by a combination of construction, size, feather quality, behavior (e.g. the crow call of long crows ) or other features. De facto , the name presupposes the recognition of a breed association with the formulation of a breed standard. Several color variations or other changing characteristics (e.g. comb shape) can be recognized within a breed. Almost all breeds also exist as dwarf breeds.

Chicken breeds worldwide

Currently, over 180 known breeds and colors are differentiated in the European poultry standard. Many other varieties are bred all over the world, some with extreme characteristics or an extraordinary adaptation to climatological conditions such as cold or drought.

Relevance of pedigree poultry farming

In order to preserve biodiversity , the breeding of pedigree chickens is desirable, but this breeding work is almost only done by hobby breeders. Purebred chickens play almost no role economically, in the agricultural industry , a few hybrid chickens "optimized" for rapid growth or high laying performance, depending on the intended use, dominate , the genetic material of which is owned by a few international corporations. Old breeds are very often so-called dual -purpose breeds that lay large numbers of eggs and also gain weight quickly enough to be used as slaughter cattle . Traditional dual-purpose chicken breeds are, for example, Australorp , German Reichshuhn , Lakenfelder Huhn , Sulmtaler , Sundheimer , Vorwerkhuhn , German sparrowhawk and Welsumer .

Hybrid chickens

Hybrid breeds are mostly used in commercial meat and egg production (see poultry ). There are around 44 million laying hens in Germany. The one-sided breeding for one performance characteristic means that there is no market requirement for male chicks, since they cannot lay eggs and, as broilers, grow too slowly and have a high need for food. Therefore, the chicks are killed within a few hours of hatching. There are therefore individual attempts to return to dual use also in conventional hybrid chicken breeding . Female dual-purpose chicken chicks are raised as laying hens. Male chicks of the dual-purpose chicken are separated when they are around three weeks old and fattened for later meat use.

Production and consumption

Increase in consumption

Chicken has seen an unusual increase in demand over the past few decades. The global consumption of chicken meat more than quadrupled between 1960 and 2010 from 2.4 kg to 11 kg per capita. The following reasons are mentioned for this: In the increasingly overnourished western world, the need for low-fat meat increased. In the developing and emerging countries, the lack of cooling options is proving to be the decisive factor. While a chicken can be eaten by a family in a day, there is a lack of suitable storage facilities for remaining meat from slaughtered pigs or cattle. Another reason can be seen in the economically extremely efficient rearing of chickens. After hatching, a chick weighs around 40 grams, after two weeks around 10 times and after a month the broiler chicken reaches its slaughter weight of around 1.5 kilograms. A chicken needs around 1.6 kg of feed to produce 1 kg of meat. For comparison: a pig needs 3 kilograms, a beef 8 kilograms. 50 years ago a chicken had to eat three times as much (5 kilograms) and it took twice as much time (two months). Further increases in productivity result from the fact that only 3% of the animals die during fattening, while it used to be up to 20%. This is attributed to improved hygiene and more effective use of medication. While 6 billion animals were slaughtered in 1960, 50 years later the figure was 45 billion.

Relevance of chicken meat

The importance of the domestic chicken for human nutrition can also be seen in the unrest triggered by rising egg and chicken prices. Street demonstrations broke out in 2012 when, in Mexico, the country with the highest per capita egg consumption, millions of domestic chickens had to be killed due to avian flu and the price of eggs doubled as a result. Rising chicken prices were one of the triggers that contributed to the 2011 revolution in Egypt . The widespread corruption in business and administration was commented on by the protesters with, among other things, the rallying cry: “You eat pigeons and chickens while we eat beans every day.” For fear that something similar would happen in Iran, during the same period the ban Iranian police chief set the national TV station to broadcast pictures of people eating chicken after chicken prices tripled in the country.

Brother chick problem

Due to the commercialization and intensification of chicken farming, billions of chicks are killed worldwide every year because they are not economical enough. These are mostly the male chicks of laying hens . In Europe, this practice is seen as questionable from the point of view of animal welfare .

Induced moulting in egg production

In most modern egg production contexts, domestic chickens are kept in production cycles and regularly replaced with a new population if there are economic reasons to do so. To prolong the population cycle of a population beyond a laying period, one induces moulting, as chickens renew their reproductive organs during this process. With an induced moult, chickens can be used for one or two additional periods in industrial egg production with laying quantities that are often only slightly below the maximum values of the first season. For the USA, it was estimated in 2003 that in 70% of the chicken population moulting is induced by food deprivation. Induction of moulting through deprivation of food or water is prohibited in the UK.

From around the 1950s, the lighting, temperature and other environmental parameters, and thus the time of the moult, were controlled in larger hen houses. Historically, the moulting of chickens was induced by the onset of winter and the associated shortened daylight periods and other environmental stress . This led to rising market prices as eggs became scarce during this time. Therefore, chicken farmers had an interest in delaying the moulting of their chickens as long as possible in order to benefit from the high prices. In modern production contexts, there is no stress effect that would cause chickens to moult, which leads to a decrease in the number of eggs after about one laying season and to a poorer usability of the eggs.

In order to induce moulting, the population is left to starve for 7-14 days - in experiments up to 28 days. During this period the chickens lose about 30% of their body weight and feathers. According to educational literature, the death rate during moulting can ideally be kept at 1.25% in the one to two week period (the average death rate in commercial laying farms is 0.5–1% per month during a production cycle).

In addition to complete food deprivation, there is also the possibility of only giving certain food in order to induce moulting due to a lack of certain nutrients. The method in Morley A. Jull : Poultry Husbandry is considered to be the first description of an induced moult . (1938 McGraw-Hill).

The largest chicken producers

The three most important chicken producing countries are the USA , China and Brazil . The most important European producers are Spain , Great Britain and France .

| rank | country | Production in thousand tons |

rank | country | Production in thousand tons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 15,536 | 11 | Russia | 1,060 |

| 2 | China | 9,475 | 12 | South Africa | 973 |

| 3 | Brazil | 8,668 | 13 | Canada | 950 |

| 4th | Mexico | 2,250 | 14th | Turkey | 940 |

| 5 | India | 1,650 | 15th | Argentina | 885 |

| 6th | Spain | 1,268 | 16 | Thailand | 878 |

| 7th | Great Britain | 1,242 | 17th | Malaysia | 825 |

| 8th | Japan | 1,241 | 18th | Iran | 820 |

| 9 | France | 1,135 | - | ||

| 10 | Indonesia | 1,100 | - |

Types of husbandry

- Poultry production

- Outdoor enclosure

- Free range

- Small group housing

- Mobile stable system

- Chicken tractor

- Organic farming

The domestic chicken in art

Movies

- In the experimental short film schwarzhuhnbraunhuhnschwarzhuhnweißhuhnrothuhnweiß or put-putt a chicken plays the main role. The 1967 film by Werner Nekes shows a chicken eating and then dying.

- In the stop-motion film Chicken Run , chickens appear as the main characters.

- The chicken “Chocolate” is the big star in a Swiss TV commercial.

- Children's film River Cruise with Chicken from 1984.

- The Festival of the Chicken is an Austrian mockumentary productionstaged in 1992for the show kunst-pieces .

- Animated film: Heaven and Chicken . (2007)

Others

- A domestic chicken rooster is a member of the Bremen Town Musicians in the Brothers Grimm fairy tale of the same name .

- I Wish I Was a Chicken is a popular song from the 1930s.

See also

- Poultry production

- Chicken egg

- Salmonella in laying hens

- Poultry growing

- Inheritance of color and markings in the domestic fowl

literature

- F. Akishinonomiya et al .: Monophyletic origin and unique dispersal patterns of domestic fowl. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA - PNAS) 93, 1996, ISSN 0027-8424 , pp. 6792-6795, online (PDF; 1.1 MB) .

- Erich Baeumer: The "stupid chicken" - behavior of the domestic chicken. Franckh'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart 1964.

- Norbert Benecke : Man and his pets. The story of a relationship that goes back thousands of years. License issue. Parkland-Verlag, Cologne 2001, ISBN 3-88059-995-5 .

- Wolf Herre , Manfred Röhrs: Pets - seen from a zoological perspective. Fischer, Stuttgart a. a. 1990, ISBN 3-437-20446-7 .

- Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World - the epic saga of the bird that powers civilization. Duckworth Overlook, London 2015, ISBN 978-0-7156-5026-4 . (e-book)

- Ekaterina A. Pechenkina, Stanley H. Ambrose, Ma Xiaolin, Robert A. Benfer Jr .: Reconstructing northern Chinese Neolithic subsistence practices by isotopic analysis. In: Journal of Archaeological Science. 32, 2005, ISSN 0305-4403 , pp. 1176–1189, online (PDF; 380 kB) ( Memento from November 19, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- Beate Peitz, Leopold Peitz: Keeping chickens. 6th edition. Ulmer, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8001-5086-7 .

- Hans Reichstein: Osteological evidence of the occurrence of crested chickens in the early modern period in Göttingen and Höxter. In: Mostefa Kokabi, Joachim Wahl (Ed.): Contributions to archeozoology and prehistoric anthropology. 8th working meeting of osteologists, Constance 1993 in memory of Joachim Boessneck. (= Research and reports on prehistory and early history in Baden-Württemberg. 53). K. Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8062-1155-8 , pp. 449-450.

- Katrin Juliane Schiffer, Carola Hotze: Keeping chickens - species-appropriate and natural. Franckh-Kosmos Verlag, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-440-10835-2 .

- Esther Verhoef, Aad Rijs: The Complete Encyclopedia of Chickens. REBO Publishers, Lisse 2006, ISBN 90-366-1592-5 .

- Frederick E. Zeuner: History of Domestic Animals. Bayerischer Landwirtschaftsverlag, Munich a. a. 1967. (Original edition: A history of domesticated animals. Hutchinson & Co., London 1963)

Web links

- The high flyer. In 1960 people slaughtered six billion chickens. In 2010 it will be 45 billion. What has happened there? . In: SZ-Magazin . Issue 47, 2010.

- J. Eriksson, G. Larson, U. Gunnarsson, B. Bed'hom, M. Tixier-Boichard and others: Identification of the Yellow Skin Gene Reveals a Hybrid Origin of the Domestic Chicken. In: PLOS Genetics . 4 (2), 2008. doi: 10.1371 / journal.pgen.1000010

- Roosters use fake mating to get their chickens to remain loyal. In: Wissenschaft.de . July 12, 2005.

- Chicken. Message from the egg. Research. In: Der Spiegel . No. 8, February 19, 1964.

- European association for rabbit, poultry, pigeon and cavia breeding

- Association of German Poultry Breeders eV

- Feathers of the domestic chicken

- Keeping chickens - information from the Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office

Individual evidence

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Introduction, ebook position 72.

- ↑ Reiner Stadler: The high flyers. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin. No. 47, November 26, 2010, p. 14 ff.

- ↑ Report on a Record giant chicken on worldrecordchicken.com , accessed on June 10, 2018

- ^ Bärbel Bauermann: Poultry farming, poultry farming. Deutscher Landwirtschaftsverlag, 1962, p. 37.

- ↑ Basic knowledge of MTool , p. 8.

- ^ Esther Verhoef, Aad Rijs: The Complete Encyclopedia of Chickens. P. 227.

- ↑ Can chickens fly? In: Hamburger Abendblatt . July 24, 2010, accessed July 4, 2012 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Wiltschko , Rafael Freire, Ursula Munro et al .: The magnetic compass of domestic chickens, Gallus gallus. In: Journal of Experimental Biology. Volume 210, 2007, pp. 2300-2310, doi: 10.1242 / jeb.004853 .

- ↑ Undeterred: The rooster crows according to its internal clock. In: Spiegel Online .

- ↑ V. Martinec, W. Bessei, K. Reiter: The influence of beak docking on feed intake and pecking after a feather dummy in 14-month-old laying hens. 2002. ulmer.de (PDF; 217 kB)

- ↑ Katrin Juliane Schiffer, Carola Hotze: Keeping chickens - species-appropriate and natural. Franckh-Kosmos Verlag, Stuttgart 2009, p. 31.

- ↑ Lori Marino: Thinking chickens: a review of cognition, emotion, and behavior in the domestic chicken. 2007, doi: 10.1007 / s10071-016-1064-4 .

- ↑ Erich Schwarze, Lothar Schröder: Compendium of the poultry anatomy. 4th, revised edition. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Jena 1985.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: The Cornelia Beard. ebook position 703.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: The Cornelia Beard. ebook position 723.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: The Cornelia Beard. ebook position 717.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: The Cornelia Beard. ebook position 516.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: The Cornelia Beard. ebook position 536.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: The Cornelia Beard. ebook position 550.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: Essential Gear. ebook position 1194.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: Essential Gear. ebook position 1180.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: Essential Gear. ebook position 1260.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: Essential Gear. ebook position 1200.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: Essential Gear. ebook position 1214.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: Essential Gear. ebook position 1234.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: Essential Gear. ebook position 1273.

- ^ Esther Verhoef, Aad Rijs: The Complete Encyclopedia of Chickens. P. 12.

- ^ A b Esther Verhoef, Aad Rijs: The Complete Encyclopedia of Chickens. P. 13.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: Giants upon the Scene. ebook position 1871.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: Giants upon the Scene. ebook position 1878.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: Giants upon the Scene. ebook position 2047.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Chapter: Giants upon the Scene. ebook position 2067.

- ↑ List of recognized large fowl of the Entente Européenne d'Aviculture et de Cuniculture (2016) , accessed on June 10, 2018

- ↑ Genetic diversity in domestic chickens. In: Landbauforschung - vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research. Special issue 322, 2008, pp. 42–56.

- ↑ pastoralpeoples.org

- ^ Esther Verhoef, Aad Rijs: The Complete Encyclopedia of Chickens. P. 123.

- ↑ Henning Biedermann: The new dual-purpose chicken. ( Memento of December 26, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ↑ Hessischer Rundfunk: dual-purpose chicken: animals for meat and eggs. ( Memento from April 15, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Christian Hetzenecker: dual-purpose chicken LesBleues. ( Memento from February 6, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ) (December 13, 2012)

- ↑ Reiner Stadler: The high flyers. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin. No. 47, November 26, 2010, p. 14 ff.

- ↑ Enoughmovement - Food Secure 2050 ( Memento of the original from July 16, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed July 15, 2015.

- ^ Andrew Lawler: Why did the Chicken cross the World. Introduction, ebook position 113.

- ↑ M. Yousaf, AS Chaudhry: History, changing scenarios and future strategies to induce moulting in laying hens. In: World's Poultry Science Journal. 64, 2008, pp. 65-75.

- ↑ DEFRA : laying hens - code of recommendations for the welfare of livestock (PDF; 108 kB)

- ^ AB Molino, EA Garcia, DA Berto, K. Pelícia, AP Silva, F. Vercese: The effects of alternative forced-molting methods on the performance and egg quality of commercial layers. In: Brazilian Journal of Poultry Science. 11, 2009, pp. 109-113.

- ^ AB Webster: Physiology and behavior of the hen during induced moult. In: Poultry Science. 82, 2003, pp. 992-1002.

- ^ Mack O. North, Donald D Bell: Commercial Chicken Production Manual. 4th edition. Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1990, p. 438.

- ↑ D. Patwardhan, A. King: Review: feed withdrawal and non feed withdrawal moult. In: World's Poultry Science Journal. 67, 2011, pp. 253-268.

- ↑ RU Khan, Z. Nikousefat, M. Javdani, V. Tufarelli, V. Laudadio: Zinc-induced moulting: production and physiology. In: World's Poultry Science Journal. 67, 2011, pp. 497-506. doi: 10.1017 / S0043933911000547 .

- ↑ The world in numbers. In: Handelsblatt. 2005

- ↑ Schweizer Illustrierte: “Chocolate” sees red