Kasimir Severinovich Malevich

Kazimir Severinovich Malevich ( Russian Казимир Северинович Малевич ., Scientific transliteration Kazimir Severinovič Malevič , Ukrainian Казимир Северинович Малевич Kasymyr Sewerynowytsch Malewytsch , Polish Kazimierz Malewicz ; born February 11, jul. / 23. February 1878 greg. In Kiev ; † 15. May 1935 in Leningrad ) was a painter and main exponent of the Russian avant-garde , pioneer of constructivism and founder of suprematism . He was influenced by late impressionism , fauvism and cubism . His abstract suprematist painting The Black Square on a White Background from 1915 is considered a milestone in modern painting and is known as an “ icon of modernity”.

Life

Childhood and youth

His father Severyn Malewicz (Russian Sewerin Antonowitsch Malewitsch, 1845–1902) and his mother Ludwika (Russian Lyudwiga Alexandrowna, 1858–1942) were of Polish origin, who after the January uprising of 1863, which had been put down by Imperial Russian troops , from the Russian-occupied Kingdom of Poland to the Kyiv Governorate (now Ukraine ) within the Tsarist Empire . Both parents were Catholics , in addition to Polish , Russian and Ukrainian were spoken in the family . Malevich himself referred to himself alternately as Ukrainian or Pole, depending on the right intention, but later in life denied any nationality.

Malevich's father was a technical clerk in various sugar beet factories in Podolia and Volhynia . Because of the frequent job changes, Malevich had an unsteady childhood in meager circumstances. Malevich completed his extremely rudimentary school education with a five-year apprenticeship at an agricultural school. However, he was already interested in drawing from nature when he was 13 years old. Three years later he was inspired by a “house painter who painted the roof and mixed a green like the trees, like the sky. That gave me the idea that this color could be used to represent a tree and sky. [...] But the pencil annoyed me very much and I finally threw it away to pick up the brush. "

education

The family moved to Kursk in 1896 , where the father accepted a position in the administration of the Kursk – Moscow railway company and gave his son a position as a draftsman. Malevich found like-minded autodidacts there who painted exclusively from nature and whom he joined.

In 1901 he married Kazimiera Sgleitz, a Polish woman. His father thwarted all his attempts to apply to the Moscow Art Academy, but in the fall of 1904 Malevich had saved enough money to study at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture by 1905 .

An initial experience for Malevich in 1904 was the sight of Claude Monet's painting of the Cathedral of Rouen , which was in the collection of the art patron Sergei Shchukin in Moscow. “For the first time I saw the light-filled reflections of the blue sky, the pure, transparent hues. […] From that moment on I became an impressionist . ”From 1905 to 1910 he continued his training with studies at Fyodor Rerberg's private studio in Moscow .

Artistic beginning

In 1907 Malevich's family finally moved to Moscow, and in the same year his first public exhibition of twelve sketches took place as part of the 14th exhibition of the Association of Moscow Artists, alongside artists who were also largely unknown, such as Wassily Kandinsky , Mikhail Fyodorovich Larionov and Natalija Sergejewna Goncharova . In 1909 Malevich married Sofija Rafalowitsch, the daughter of a psychiatrist, for the second time. The following year he took part in the exhibition organized by Larionov and Goncharova by the artist group " Jack of Diamonds ". His neo-primitivist period began in 1910 , during which he painted, for example, the floor polishers , a painting with a significantly reduced spatial perspective.

Goncharova and Larionov separated in 1912 from the group "Karo-Bube", which appeared to them to be westernized, and founded the artists' association " Donkey Tail " in Moscow, in which Malevich participated. At an exhibition of this association he met the painter and composer Mikhail Wassiljewitsch Matjuschin . The acquaintance led to a stimulating collaboration, and a lifelong friendship developed between the two artists.

Larionov had previously been the leader of the avant-garde, but as a result of Malevich's growing demands, a rivalry for leadership developed, which was also rooted in various artistic concepts. Malevich turned to cubofuturism , which he presented in St. Petersburg at the "Union of Youth" during a lecture as the only defensible direction in art. He painted some pictures in this style until 1913, for example the painting The Lumberjack . His work was also represented overseas in the Armory Show (International Exhibition of Modern Art) in New York in 1913.

The opera Victory over the Sun , Justification of Suprematism

In the summer of 1913, work on the composition of the opera Sieg über die Sonne began in Uusikirkko (Finland) with Malevich's participation . The futuristic work premiered on December 3, 1913 in the Lunapark Theater in Saint Petersburg . Velimir Chlebnikow wrote the prologue, Alexei Krutschonych the libretto, the music was by Mikhail Matjuschin and the set and costumes by Malevich. He drew the first black square on a stage curtain . This is also the reason why Malevich shifted the birth of Suprematism to 1913 and did not refer to the suprematist images of 1915 in the true sense of the word. In March / April 1914 an exhibition took place in the “ Salon des Indépendants ” in Paris , at which Malevich was represented with three paintings.

In 1915 he wrote the From Cubism to Suprematism manifesto . The new painterly realism - with the black square on the cover - and presented his suprematist painting The Black Square on a White Background for the first time in December in the exhibition Last Futurist Exhibition " 0.10 " in the Dobytschina Gallery in Petrograd (from 1914 to 1924 of Name for Saint Petersburg), which was called a square in the catalog . The mysterious number 0.10 denotes a figure of thought: zero because it was expected that after the destruction of the old the world could start again from zero, and ten because ten artists originally wanted to participate. In fact, there were fourteen artists who took part in the exhibition.

Malevich hung his square diagonally above in the corner of the wall under the ceiling of the room, a Russian icon usually had its traditional place there. The exhibitors included Malevich Vladimir Tatlin , Nadeschda Udalzowa , Lyubow Popowa and Ivan Puni .

The exhibition, which received scathing reviews, marks the breakthrough to non-representational, abstract art; the groundbreaking event in art history did not attract international attention at the time, as war had broken out in Europe. Malevich was drafted into the tsarist army in 1916 and spent the time in an office until the end of the war. During this time he continued to work on his paintings and theoretical writings and corresponded with Matyushin. Although the Russian avant-garde groups had different theories, which led to controversy, under the harsh war conditions there were joint art exhibitions of the Suprematists under Malevich's leadership and the constructivists, which Tatlin led. For example, at Tatlin's request, Malevich made older cubo-futuristic works available, such as An Englishman in Moscow , which were included in his Magasin exhibition in a department store.

After the October Revolution of 1917, Malevich was entrusted with the supervision of the Kremlin's national art collections . He became chairman of the art department of the Moscow City Soviet and a master at the second "Free State Art Workshop" (SWOMAS) and professor at the "Free State Art Workshop" in Petrograd. In the narrower sense he was neither a committed functionary nor a revolutionary, he only used the new rulers to enforce his artistic ambitions. His painting had established itself in the art scene; for example, in autumn 1918 he and Matyushin were commissioned to create the decorations for a congress on village poverty in the Winter Palace .

Flower seller , dated 1903, actually only created towards the end of the 1920s, Russian Museum , St. Petersburg

Landscape (The Winter) , dated 1909, but actually not created until 1930, Museum Ludwig , Cologne

Bathers , 1911, Stedelijk Museum , Amsterdam

Solar eclipse with Mona Lisa , 1914, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Suprematism (Supremus No. 58) , 1916, Krasnodar Art Museum

Vitebsk period

At the invitation of Marc Chagall to work in the folk art school he organized in 1918 (Pravda Street 5), Kazimir Malevich arrived in Vitebsk in 1919 . Malevich founded the group UNOWIS (Confirmers of New Art) there in 1920 and after a short time was able to gather many followers. His daughter Una was born, her name is derived from the artist group. Chagall, who had already lost the power struggle against Malevich in the dispute over the school's artistic orientation, emigrated to Paris via Berlin in 1922.

The architect and graphic designer El Lissitzky was a member of the institute; In his studio he also designed texts by Malevich such as Suprematism 34 Drawings (1920). During this historical period, under Malevich's leadership, not only the school itself, the teaching system and the cultural life of the city of Vitebsk were changed, but they also influenced the rest of the world’s art process. During Malevich's work in Vitebsk (Vitebsk period) the ideas of Suprematism were theoretically and conceptually perfected. They needed a new milieu for the development and for the multifunctional dialogue of the behavior towards renewal towards life. Vitebsk, which at that time was called the second Paris, has become this milieu. In Vitebsk, the idea of founding a museum of modern art was born and realized by Marc Chagall. Today this period is called "Vitebsk Renaissance" or "Vitebsk School".

Teaching from 1922 to 1926

In April 1922, after disputes with the authorities fighting the Russian avant-garde, Malevich and a large part of his students left Vitebsk for Petrograd ( Saint Petersburg ). In 1925, after the death of his second wife, he married Natalja Andrejewna Mantschenko for the third time. From 1924 to 1926 he was head of GINChUK . However, the regime-compliant artist group AChRR had meanwhile dominated Soviet art culture - the Stalinist era had begun and with it the rejection of avant-garde art - so that Malevich fell out of favor and lost his position in 1926. Therefore he took a job at the State Institute for Art History.

Visit to Berlin and Dessau

In the spring of 1927 Malevich received a visa and traveled via Warsaw to Berlin , where 70 paintings and his architectona , plaster models of his architectural designs, were shown in the Galerie van Diemen during the “Great Berlin Art Exhibition” . In Dessau , he visited the Bauhaus and was able to agree to the publication of his work The Objectless World , which was published as the eleventh volume in the series of Bauhaus books (founded by Walter Gropius and László Moholy-Nagy ), albeit with a distant foreword from the editors. In addition, passages were deleted from the text in which Malevich dealt critically with the development of Soviet society. In his manuscript, for example, he wrote of the “current phase of socialist, food-oriented comfort”. Contrary to his expectations, Malevich was accepted as an important representative of the Russian avant-garde, but the Bauhaus at that time was closer to Russian constructivism than to Suprematism, which in Germany with its philosophical system of world knowledge appeared to be outdated. In Dessau they were looking for a way to create a world design, similar to the Dutch group De Stijl , whose co-founder Piet Mondrian was like Malewitsch an early master of abstraction. Mondrian's neo-plasticism style, created in 1920, was influenced by Malevich's emotional suprematism.

In June Malevich returned to Leningrad; In Germany, because of the uncertain political situation in the Soviet Union, he left his writings with his host Gustav von Riesen and the works he had brought with him to the architect Hugo Häring , who kept them for Malevich. The planned renewed visit to Malevich did not take place, so that the paintings were not rediscovered until 1951 and in 1958 the Stedelijk Museum , Amsterdam bought them for around 120,000 marks . The long-standing dispute between the 37 heirs of Malevich and the city of Amsterdam was settled amicably through a settlement in May 2008: The heirs received five significant works by Malevich and in return accept that the remaining pictures will remain from the collection of the city of Amsterdam. There they have been exhibited in the reopened Stedelijk Museum since 2009.

Return to figurative painting

Malevich resumed his work at the State Institute for Art History, drew up plans for satellite cities in Moscow, worked on designs for porcelain and tried to publish his research results. In trying to slightly revise his dogmatic views, he was looking for new possibilities and avenues for his art.

Malevich began to restore the essential works that he had left behind in Germany by painting "improved" replicas ; this also applied to impressionistic motifs. He dated the work back, which would later lead to great confusion in art circles. The pictures served to complete his large retrospective, which was planned for 1929.

A radical change in Malevich's work from the late 1920s was the return to figurative painting with Suprematist elements; he placed them in the service of the beloved peasants who suffered from the forced collectivization of agriculture , which was expressed in his new style. In his style of painting, people gradually became mutilated dolls, prisoners of a criminal gulag .

He was forbidden to continue working at the State Institute for the History of Art in 1929 and the institute was closed a little later. For two weeks a month he was allowed to work at the art institute in Kiev. In November of that year he exhibited his works in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow on the occasion of a retrospective , but received mostly negative criticism. Shortly afterwards the exhibition was transferred to Kiev, but was closed again after a few days. In 1930 Malevich was arrested and brought before for two weeks for questioning.

In his last artistic phase, shortly before his death, he returned to the painting style of "real" portraits, but these do not correspond to the style of "Socialist Realism", but resemble works of the Renaissance , which is expressed in the clothing of the portrayed. The expressive gestures of the people represented are characteristic of these paintings.

In 1932 he became head of a research laboratory at the Russian Museum in Leningrad, where he worked until his death. Despite the state order that forbade avant-garde tendencies and called for the style of socialist realism , his work was shown again in the context of the exhibition “Fifteen Years of Soviet Art”. From 1935, however, there was no longer any exhibition of his works in the USSR ; only after perestroika was there a comprehensive retrospective of Malevich's works in St. Petersburg in 1988.

In 1935 Malevich died of cancer in Leningrad. His grave was in Nemtschinowka near Moscow on the site of his dacha , on which a white cube designed by Nikolai Suetin with a black square on the front was placed. The tomb no longer exists today.

To the work

The early work

At the beginning of his artistic work, Malevich oriented himself towards the innovations in European art at the beginning of the 20th century. So he initially painted in the Impressionist style and took Monet and later Cézanne as models. In his early work he also created paintings in the symbolist and pointillist style. Many elements of the Russian folk art Lubok can be found in his prints . The peasant head from 1911 is an example of the frequent use of the peasant, colorful Russian motifs. It was exhibited at the second exhibition of the Blue Rider in Munich.

Primitivism, cubofuturism, alogism

Kazimir Malevich's artistic development in the run-up to Suprematism (until 1915) is determined by three main phases: primitivism , cubofuturism and alogism . In primitivism from 1910 to around 1912, greatly simplified, two-dimensional forms and expressive colors predominated. The picture subjects related to everyday scenes; an example of this is the bather from 1911.

In contrast to primitivism, cubofuturism, a Russian modification of French cubism and Italian futurism , brought about a return to traditional forms of Russian folk art. Malevich used basic cubist forms such as cones, spheres and cylinders to depict the figures and their surroundings; the color, often tinted earthy, served to emphasize the plasticity. In many of the paintings of this period he divided the surface into facets.

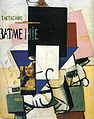

The so-called alogical paintings followed in the third phase. Traditional image meanings were replaced by alogical combinations of numbers, letters, word fragments and figures. An example is shown in the painting An Englishman in Moscow from 1914.

The prehistory of Suprematism explains Malevich's radical step to the non-representational style of Suprematism by showing the juxtaposition, the brief application of different styles and the break with the logic of the picture content.

The Suprematist Work from 1915

Main article: Suprematism

The best-known of his pictures is the Suprematist Black Square on a White Background from 1915, with which Malevich reached a climax with the abstraction he began in Cubism . In his manifesto accompanying the exhibition "(0.10)" , Malevich denied any relationship between art and its representations and nature. In doing so, he left behind the current avant-garde tendencies of the time, because Cubism did not demand the absolute non-representational nature of the pictorial content, as Malevich now used in his works. The structure of the black square was created by small impressionistic brushstrokes, not with the ruler and a uniform color surface, the edges of the square are frayed. In 1923 and 1929 he was to create more pictures with the theme "Black Square". Also in 1915 he painted The Red Square . A yellow parallelogram on white was followed by White Square in 1919 , a white square on a white background, with which the series of squares was completed. In his Suprematist paintings, besides black and white, one finds the basic colors of the palette: red, blue, yellow and green.

Malevich described the three phases of Suprematism in his work Suprematism 34 Drawings and explained the meaning of his monochrome squares as follows: “As self-knowledge in the purely utilitarian perfection of the 'All Man' in the general area of life, they have acquired another meaning: the black as a sign of Economy , the red as a signal of the revolution , and the white as a pure effect. "

Malevich was not only interested in an art form, but also in a new attitude towards life, which he described with the expression "excitement". So his writing for the exhibition of 1915 ends with the words: “I have cut the knot of wisdom and freed the consciousness of color. […] I have overcome the impossible and made the abyss my breath. But you wriggle like fish in the nets of the horizon! We, the Suprematists, pave the way for you. Hurry up! Because tomorrow you won't recognize us anymore. "

From the static stage of his painting of the squares , he went on to the dynamic or cosmic stage, which is shown, for example, in eight rectangles and an airplane in flight , both pictures were created in 1915. Through his new art form, Malevich came up with the idea that humanity could rule not only earthly space, but also the cosmos . In his writing Suprematism 34 Drawings from 1920, he mentioned the possibilities of interplanetary flight and earth satellites ( Sputniks ).

The art historian Werner Haftmann quoted the artist's interpretation of his own creation of Suprematism in the context of art history in his work Painting in the 20th Century : “He brought painting to zero through the total negation of all sources of cloudiness; What remained was the simplest geometric element - the square on the pure surface. It was not a 'picture' that Malevich had made there; it was, as he himself said, 'rather the experience of pure non-objectivity'. [...] The expressive and descriptive of abstract expressionism disappeared, the constructive gained the upper hand, with elementary and absolute forms painting could be experienced as architecture and pure, self-contained harmony. The square on the surface was not only a spontaneous symbol of the 'experience of non-representationalism', it also turned out to be the first building block of an absolute painting. "

The late work

After his return from Berlin and Dessau in 1927, Malewitsch occasionally returned to Impressionist motifs, in which he integrated Suprematist elements and which he predated to the period from 1903 onwards, since he had his exhibition in the Tretyakov Gallery in 1929 about the pictures left behind in Berlin wanted to complement. He wrote down his thoughts on the reinterpretation of Impressionism in his treatise Isologie , an art term that he had invented himself like Suprematism , and passed them on to his followers in lectures.

When his late work was released from Russian depots 20 years ago, there was criticism that the painter of radical abstraction had become a renegade of the avant-garde. In his post-suprematist works of the 1930s, Malevich returned to figurative painting; Farmer scenes were his preferred motifs. From the system of Suprematism Malevich constructed a new symbolic image of man that was far removed from any realism. He referred to the characters as “Budetljanje” (“futurist”): his farmers are increasingly becoming robots without a face, without a beard and later without arms. The premonition of the destruction of the peasant world through collectivization prompted Malevich to declare that he does not paint a face "because he does not see the people of the future" or rather "the future of the people is a mystery that cannot be fathomed".

Motifs of Suprematism appear, for example, in the shape of the square in houses without windows. The painting Head of a Peasant contains four Suprematist shapes, of which the two squares that make up the beard can be called the plowshares. But the head is also an icon (loved by Malevich) , a portrait reminiscent of a peasant figure of Christ. Airplanes can be seen in the sky, reminiscent of birds as bad harbingers; they have come to destroy the freedom and traditional culture of the peasants.

In Malevich's last phase, which he describes as “supranaturalism”, women are mostly portrayed in naturalistic form as portraits of the new person who belong to another, future world. One example is the worker as a member of a new religion, a mother and child depiction in which the missing child is replaced by the arm position and communicates with this encrypted gesture. The best known example of this last phase is his self-portrait from 1933, shown in the introduction above. Malevich presents himself in the clothes of a Renaissance painter, his hand forming the absent square. Its black square forms the signature. Malevich sums up the story of his painting with the message that human life can be reduced to a gesture.

Architects, product design

From 1923 Malevich dealt with architectural studies ; His spatial projects called architects , plaster models in a suprematist form, had not met with approval from the Bauhaus architects in 1927 and stood in contrast to Tatlin and his group in Petrograd. Housing estates for space (planites) and satellite cities (semlyanites) were a topic within his studies, which he described as "architectural formulas according to which the architectural structures can be given shape". Malevich also dealt with product design and created porcelain services in the constructivist style.

Fonts

In 1927, Malewitsch summarized his reflections in the Bauhaus book The Objectless World , which was his only book publication in Germany during his lifetime. The term “sensation”, which was important to him and which appeared in the texts of the Vitebsk period, was most clearly described in the Bauhaus pamphlet: “By suprematism I mean the supremacy of pure sensation in the visual arts. From the standpoint of Suprematism, the phenomena of objective nature are in themselves meaningless; The essential thing is the sensation - as such, completely independent of the environment in which it was evoked. ”And Malevich himself justified the theme of his late work in this:“ The mask of life hides the true face of art. Art is not what it could be to us. "

In addition to his other art theoretical writings listed below, Malevich wrote several essays on the film and a screenplay between 1925 and 1929. There is a publication The White Rectangle. Schriften zum Film (1997), most of which contains texts in German for the first time, “[…] lead to the center of the discussion about movement and acceleration as a central metaphor of modernity in the international avant-garde. […] Malevich arranges the melodramas with Mary Pickford , the comedies with Monty Banks , the films by Sergej Eisenstein , Dsiga Wertow , Walter Ruttmann and Jakow Protasanow in his historical model of the emergence of modernity from Cézanne to Cubism, Futurism - to Suprematism . Almost all of his essays are about the missed rendezvous between film and art. Because Malevich does not understand film as the perfecting of naturalism, but as principles of new painting: dynamism and non-representationalism. "

Works (selection)

For a complete overview, see the list of Kazimir Malevich's works .

painting

- 1902–1903 Laundry hung up to dry , Costakis Collection, ( State Museum of Contemporary Art (Thessaloniki) )

- 1904 Spring garden in bloom , Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg

- around 1905 Church , Costakis Collection, ( State Museum of Contemporary Art (Thessaloniki) )

- 1907 The wedding , Museum Ludwig , Cologne

- 1908 Oak and dryads , N. Manoukian collection

- 1910–1911 Self-Portrait , Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg, 1910/11

- 1910–1911 self-portrait , Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

- 1911 Bather , Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

- 1911 Argentine polka , JJ Aberbach collection

- 1911–1912 The Parquet Cleaners , Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

- 1911–1912 Study of a Peasant , Musée National d'Art Moderne , Paris

- 1913 Portrait of Mikhail Matyushin , Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

- 1914 First Division soldier , Museum of Modern Art , New York

- 1915 The Black Square , Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

- 1915 The Red Square , Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg

- 1915 black and white. Suprematist Composition , Moderna Museet , Stockholm

- 1915 Suprematist picture , Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

- 1915 Suprematist Composition , Wilhelm Hack Museum, Ludwigshafen

- 1919 White Square , Museum of Modern Art, New York

- 1928–1932 Red Figure , Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg

- 1928–1932 Girls in the Field , Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg

- 1930–1931 Woman with a Rake , Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

- 1930–1932 Peasant woman with a black face , Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg

- 1932 Red House , Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg

- 1933 Self-Portrait , Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg

- 1933–1934 Portrait of the Artist's Wife , Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg

The largest collections of Malevich's works are exhibited in the Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg and in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow . A larger collection of works by Malevich outside of Russia owns the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam , the Museum Ludwig in Cologne and the State Museum of Contemporary Art in Thessaloniki .

Fonts

" Only when the habit and awareness of seeing the representation of small corners of nature, Madonnas or Venus in pictures, will we recognize the painterly work [...] "

Entire fonts

-

From cubism to suprematism. The new painterly realism . 1st edition. Schurawl-Verlag, Petrograd December 1915 (original title: От кубизма к супрематизму. Новый живописный реализм . 2nd unaltered edition Petrograd January 1916).

- From cubism to suprematism in art, to the new realism in painting, as the absolute creation. In: Baumeister, Ch., Hertling, N. (Ed.): Victory over the sun. Aspects of Russian art at the beginning of the 20th century, Fröhlich & Kaufmann GmbH, Berlin 1983. [German translation of 1./2. Edition by Jelena Hahl]

-

From cubism and futurism to suprematism. The new painterly realism . 3rd greatly expanded edition. Moscow November 1916 (Original title: От кубизма и футуризма к супрематизму. Новый живописный реализм .).

- From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Painterly Realism. In: John E. Bowlt (Ed.): Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism, 1902-1934. The Viking Press, New York, pp. 116-135. [English translation of the 3rd edition by J. Bowlt]

- About new systems in art . Vitebsk 1919 (Original title: О новых системах в искусствею .). Edition: 1,000 copies.

- Suprematism 34 drawings , 1920. Reprint, Tübingen 1974

- Suprematist Manifesto UNOWIS . Leningrad 1924

- The non-representational world. (= Bauhaus books 11). written in 1923; Albert Langen, Munich, 1927. (New edition, edited by Hans M. Wingler, Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-7861-1475-7 )

- [Autobiography]. Manuscript published posthumously in: The Russian Avant-Garde, Alnqvist and Wiksell International, Stockholm 1976

Collective editions

- The white rectangle. Writings on the film , edited by Oksana Bulgakova . Potemkin Press , Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-9804989-2-1

- Suprematism - The Objectless World , edited by Werner Haftmann . Translated from the Russian by Hans von Riesen. Unchanged new edition of the title of the same name published in 1962, DuMont Reiseverlag, Ostfildern 1989, ISBN 3-7701-2473-1

- Essays on art 1915–1928 , edited by Troels Andersen. Vol. I., Copenhagen 1968

- Essays on art 1928–1933 , edited by Troels Andersen. Vol. II., Copenhagen 1968

- The World as Non-Objectivity. Unpublished Writings 1922–1933 , edited by Troels Andersen. Vol. III., Copenhagen 1976

- The Artist, Infinity, Suprematism. Unpublished Writings 1913–1928 , edited by Troels Andersen. Vol. IV., Copenhagen 1978

- God did not fall. Writings on art, the church, the factory . Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-446-17341-2 (The theoretical writings of the artist commented on by Aage A. Hansen-Löve.)

reception

“The world as a sensation of the idea, independent of the image - that is the essential content of art. The square is not the picture. Just like the switch and the plug are not the electricity either. "

Effect during lifetime

The first reaction to the black square in the “ 0.10 ” exhibition in 1915 was clearly negative: it was an affront to the academic and realistic style of painting; the critics reviled the picture as the "dead square", the "personified nothing". The art historian and Malevich opponent Alexander Benois called it in the Petrograd Time stem "Language" as "the, ob- tain allerabgefeimtesten trick in Carnival Booth of the very latest art." The slating the Russian writer concluded Dmitri Merezhkovsky in which "from the invasion the bully in culture ”spoke. Vladimir Tatlin's no less revolutionary corner reliefs got off almost scot-free. Perhaps this was due to the fact that Malevich had made many enemies for himself through polemical appearances at public events. To attract attention, Malevich and his students wore red wooden spoons in the breast pocket of their jackets, which were cut as yellow smocks, instead of the decorative cloths. […] Despite all the criticism, Suprematism began to prevail, as there was still no binding art doctrine “from above” in Russia and friends and followers supported Malevich's claim to leadership within the avant-garde and his new style of painting.

Marc Chagall, who was defeated by Malevich in the dispute over the management of the art school in Vitebsk, wrote resignedly to Pawel D. Ettinger in 1920: “The movement has reached its boiling point. A sworn group of students has formed around Malevich, another around me. We both belong to the left, but have completely different ideas about their goals and methods. "

On his trip to Berlin and Dessau in 1927, Malevich had not correctly assessed the development of art in Germany, because it was above all constructivism and the Bauhaus that determined the direction there. He said: "It seems to me that Suprematism is presented here for the first time as the final end for all constructivism and as the basis of life [...] The work in Germany is good because all of this is now known all over the world." At the Bauhaus, he only met the director Walter Gropius briefly and expressed his desire to stay in Germany. It is possible that after his dismissal he hoped for new teaching assignments at the Bauhaus. However, Malevich had no success with his visit and left again. The only income was the publication of his book Die Subjectlose Welt (1927/28). The editor, László Moholy-Nagy, had clearly stated in the foreword: "We are pleased to be able to publish the present work by the important Russian painter Malevich [...], although it deviates from our point of view on fundamental issues."

Wassily Kandinsky wrote in the Cahiers d'Art 1931: "The meeting of the acute angle of a triangle with a circle has no less effect than the contact between the finger of God and Adam in Michelangelo ".

Voices on the late work

Hans-Peter Riese , Malewitsch's biographer, commented on the problem of predated images. Malevich's reception history had to be rewritten when the Iron Curtain was lifted in the 1980s and his late works could be shown in the West from 1927. His artistic transformation aroused great astonishment, as his return to figurative painting was contrary to the previously known high point of his work, abstract Suprematism. The first cataloging took place after the dating of the pictures, which Malevich himself had done. The Impressionist-influenced images were taken in the first decade of the last century as the artist had labeled them. In fact, most of these works were only created in the 1930s. At that time, Malevich practically reconstructed his early work and brought the date forward, as research by the Bulgarian art historian Andrei Nakov showed, who published the general catalog of Malevich in 2002 and is considered a leading Malevich researcher.

Sebastian Egenhofer in the introduction to an art history seminar on Malewitsch's late work: “Malewitsch calls the figurative painting of the past“ feeding trough realism ”because it only allows for“ non-objective excitement ”in the horizon of hunger, of practical interest, ie. H. conceived and represented as objectivity. Malevich's figurative late work, which emerged after various attempts from 1928, on the other hand, would be a "feeding trough realism" that understands itself. Malevich finds the Suprematist color fields - the next spatial representation of the "non-objective excitement" in the plane of intersection of the abstract pictures of the decade - in the earth and the fields of the farmers. The reflection within the painting is intertwined with a cosmological-economic one. The non-representational is the giving nature (not the appearing nature) in the grip of the "agricultural industry" as a kind of abstract painting. "

Malevich's influence on contemporary and later artists

The painter and sculptor Imi Knoebel reported on his years as a student in Düsseldorf in the early 1960s: “That was when this book came out, The Objectless World of Malevich, his texts. We were fascinated by the black square . For us, that was the phenomenon that had completely captured us, that was the real change. We literally peddled Malevich with this awareness. ”At about the same time, Blinky Palermo , a Beuys student like Knoebel, was painting his composition with eight red rectangles, his first geometric picture in 1964. His prototypes also look like childish illustrations of Malevich's basic work.

The exhibition The Black Square - Homage to Malewitsch , which opened in Hamburg in spring 2007 and for which the installation artist Gregor Schneider designed a cube hung with black fabric, the Cube Hamburg 2007 , on the forecourt of the Hamburger Kunsthalle , was a crowd puller. Since the black cube is not only reminiscent of the Black Square , but also of the Muslim Kaaba in Mecca , terrorist attacks were feared, but they did not occur. The painting The Black Square was exhibited in its version from 1923.

Heiko Klaas summed up the strong influence of Malevich on his contemporaries and subsequent generations of artists in the exhibition Spiegel : “If you follow the thesis of the exhibition, the black square kicked off at least every second art and design trend of the 20th century. It appears on textile designs as well as on Russian railway wagons and shop signs. Malevich's contemporaries, El Lissitzky and Alexander Rodtschenko, spiced up their constructivist graphics, architectural designs and spatial constructions with derivatives and variants. Artists of American minimal and conceptual art such as Donald Judd , Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt multiplied the square and created serial sculptures from readily available industrial materials such as steel. For them, too, it was about an elementary design language. They radically distanced themselves from the gestural painting of their time, action painting and abstract expressionism . "

On the occasion of the Hamburg exhibition, the newspaper Die Welt named other artists who based their works on the black square and gave the “master of the abstract” a tribute with their work quote: “ Samuel Beckett let hooded men run in squares, Noriyuki Haraguchi filled tubs with black waste oil, Günther Uecker nailed the square, Reiner Ruthenbeck tried to lighten a black square with spotlights, while Sigmar Polke painted a picture with a black corner and wrote on the edge: "Higher beings ordered: paint the top right corner black!" "

Petra Kipphoff quoted at the Malevich exhibition at the time the pathetic words of the artist in a letter in 1918 to the Russian painter, art historian and editor of the art journal Mir Iskusstva , Alexander Benois , "I have painted my time naked icon ... the Royal in his Lack of words ”. Kipphoff describes the effect the painting has on the viewer: “And when you approach the picture, the black square unfolds its royal, iconic effect. Nothing can be seen on this intensely and slightly bumpy painted canvas, but it is precisely in this non-objective excitement (a word which, like 'sensation', is often used by Malevich) any knowledge is possible ”.

Appreciation

In the late 1940s, George Costakis began to collect works by Malevich and other artists of the Russian avant-garde and to research the life and environment of the artist, who was ostracized in his homeland.

Gilles Néret, Malevich's biographer, counts the artist among the four most important protagonists of modern art of the 20th century, as he sums up in the introduction to his book Malewitsch : “ Baudelaire asked the question: 'What is modernity?' It took some time before the four protagonists and pillars of 20th century art could give an answer to the poet's question: Picasso , by atomizing forms, Matisse , by emancipating color, Duchamp , by promoting the destruction of the " Ready-made " invented a work of art , and Malevich by creating - like a crucifix - his icon black square on a white background . "

Exhibitions (selection)

- 1905: Exhibition of painters from Kursk and other cities . Kursk

- 1906: 25th periodical exhibition of the Society of Art Lovers . Moscow

- 1912–13: First exhibition of the Society “Free Art / Modern Painting” . Moscow

- 1915: First futuristic exhibition Tramwaj W. Petrograd

- 1915–16: The last futuristic exhibition of painting 0.10 (zero – ten) . Nadeschda Dobytschina Art Office, Petrograd

- 1919: Kazimir Malevich. His path from impressionism to suprematism. (16th State Exhibition of the ISO ) Moscow

- 1959: II. Documenta '59. “Art after 1945, painting - sculpture - graphic prints” . kassel

- 1978: Malevitch. Center Georges Pompidou , Paris

- 1980: Kasimir Malewitsch 1878–1935. Works from Soviet collections. Municipal art gallery Düsseldorf

- 1988: Retrospective of the works in the Tretyakov Gallery , Moscow

- 1989: Retrospective of the works in the Stedelijk Museum , Amsterdam

- 1995: Kazimir Malevich. Work and effect. Museum Ludwig , Cologne

- 2000: Exhibition in the Kunsthalle Bielefeld on Malewitsch's late work

- 2001: Kunstforum Wien , Vienna

- 2003/04: Mondrian and Malewitsch . Fondation Beyeler , Riehen near Basel

- 2007: The Black Square . Hamburger Kunsthalle

- 2008: Malevich and his influence . Liechtenstein Art Museum , Vaduz

- 2008/09: From surface to room. Malevich and the early modern age . Large state exhibition for the 100th anniversary of the State Art Gallery Baden-Baden

- 2010: Kasimir Malewitsch and Suprematism in the Ludwig Collection . Museum Ludwig, Cologne

- 2013: Malevich and the Russian avant-garde . Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. With works from the Costakis and Khardzhiev collections.

- 2014: Kazimir Malevich and the Russian avant-garde . Bundeskunsthalle , Bonn (March 8 to June 22, 2014), bundeskunsthalle.de

- 2016: Chagall to Malevich | The Russian avant-garde. Albertina , Vienna, February 26 to June 26, 2016

- 2018/19: Goncharova and Malevich: In Three Dimensions. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, June 5, 2018 to June 1, 2019

literature

- Hubertus Gaßner (Ed.): The Black Square. Tribute to Malevich . Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern 2007, ISBN 978-3-7757-1948-3

- Werner Haftmann : Painting in the 20th Century. A story of development . Munich 1965, the first edition appeared in 1954. As a paperback: Prestel Verlag, Munich, 9th updated edition 2000, ISBN 3-7913-0491-7

- Jean-Claude Marcadé: Kazimir S. Malevich . Nouvelles Éditions Française, Paris 1990, ISBN 2-7079-0025-7

- Andrei Nakov: Kazimir Malewicz: Catalog Raisonné . Biro, Paris 2002, ISBN 2-87660-293-8 .

- Andrei Nakov: Kazimir Malewicz le peintre absolu. Four volumes in one cassette. Thalia edition, Paris 2007, ISBN 978-2-35278-012-0 .

- Gilles Néret: Malevich . Taschen Verlag, Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-8228-1960-3 (cited from this edition)

- Gilles Néret: Kasimir Malewitsch 1878-1935 and Suprematism. Taschen Verlag, Cologne 2017, ISBN 978-3-8365-4635-5

- Hans-Peter Riese : Kasimir Malewitsch . Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek 1999, ISBN 3-499-50465-0

- Jeannot Simmen: Kasimir Malewitsch. The black square . Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt a. Main 1998, ISBN 3-596-12419-0 .

- Jeannot Simmen and Kolja Kohlhoff: Malewitsch life and work . Könemann Verlag, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-8290-2684-6

- Heiner Stachelhaus: Kasimir Malewitsch. A tragic conflict . Claassen Verlag, Düsseldorf 1989, ISBN 3-546-48681-1

- Kasimir Malewitsch - Sculptural models of thought . In: Markus Stegmann: Architectural Sculpture in the 20th Century. Historical aspects and work structures . Tübingen 1995, pp. 84-92.

Movie

- The Russian Revolutionary: Zaha Hadid on Kazimir Malevich. Documentary, Great Britain, 2014, 29:30 min., Written and directed by Martina Hall, production: BBC Scotland, series: Secret Knowledge, first broadcast: September 9, 2014 on BBC Four , synopsis with excerpts from BBC Four.

Web links

- Literature by and about Kasimir Severinovich Malevich in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Kasimir Severinovich Malevich in the German Digital Library

- Materials by and about Kasimir Malevic in the documenta archive

- Kasimir Severinovich Malevich on kunstaspekte.de

- Oksana Bulgakowa (ed.): The White Rectangle: Kazimir Malevich on film.

items

- Roland Enke: Malevich and Berlin - an approach. In: db-artmag.com , 2003, see also: Introduction .

- Christian Semler : Malevich and the Bolsheviks. In: db-artmag.com , 2003

- Hans-Peter Riese : The painter of the absolute. Andrei Nakov's impressive description of the work by Kasimir Malewitsch. ( Memento of October 22, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) In: FAZ , November 19, 2007, on Nakov's extensive work on Malevich

Exhibitions

- Malevich at Tate Modern , video

- Hanno Rauterberg : The image of the non-image. In: Die Zeit , March 23, 2000, No. 13; for the Bielefeld exhibition on Malewitsch's late work 2000

- Petra Kipphoff : Black fabric. Kasimir Malewitsch, the »Black Square« and its consequences - an exhibition in the Hamburger Kunsthalle. In: Die Zeit , April 1, 2007, No. 14

Individual evidence

- ↑ The Black Square. Homage to Malevich ( Memento from February 23, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), hamburger-kunsthalle.de, 2007

- ↑ Hans-Peter Riese: Kasimir Malewitsch , p. 9

- ↑ Myroslav Shkandrij, Reinterpreting Malevich: Biography, Autobiography, Art, "Canadian-American Slavic Studies", Vol. 36. No. 4 (Winter 2002), 2002, pp. 405-420.

- ↑ Autobiographical Notes , printed in a German translation by Günther Hanne in Kasimir Malewitsch. For the 100th birthday . Catalog of the Gmurzynska Gallery, Cologne 1978, pp. 15, 17

- ↑ Gilles Néret: Malewitsch , p. 13

- ↑ Hans-Peter Riese: Kasimir Malewitsch . P. 26

- ↑ Gilles Néret: Malewitsch , p. 47

- ↑ Katrin Bettina Müller in: www.db-artmag.de, see web link (accessed on July 1, 2008)

- ↑ Gilles Néret: Malewitsch , p. 50

- ↑ Hans-Peter Riese: Kasimir Malewitsch , p. 73 f

- ↑ Gilles Néret: Malewitsch , p. 73

- ↑ Gilles Néret: Malewitsch , p. 72

- ↑ Hans-Peter Riese: Kasimir Malewitsch , p. 145. In 1914, after Germany declared war on Russia, St. Petersburg was given the Russian name Petrograd, renamed Leningrad in 1924, and in 1991 back to the original name St. Petersburg.

- ↑ Noemi Smolik, Fressorientierter Sozialismus , in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , July 1, 2019, p. 11.

- ↑ Hans-Peter Riese: Kasimir Malewitsch , p. 110 f

- ↑ Gilles Néret: Malewitsch , pp. 73, 92

- ^ Lisa Zeitz: Malevich restitution case. Happy ending. ( Memento from April 16, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) In: FAZ , May 17, 2008.

- ↑ Hans-Peter Riese: Kasimir Malewitsch , p. 124 f

- ↑ Gilles Néret: Malewitsch , p. 76 ff

- ↑ Gilles Néret: Malewitsch , p. 94

- ↑ Kazimir Malevich and Suprematism. art-in.de, February 6, 2003, accessed July 4, 2008 .

- ↑ Gilles Néret: Malewitsch , p. 61

- ↑ Hans-Peter Riese: Kasimir Malewitsch , pp. 62 ff, 84

- ↑ Gilles Néret: Malewitsch , p. 65. See also Marie-Luise Heuser : Russian cosmism and extraterrestrial suprematism . In: Planetary Perspectives . Marburg 2009, pp. 62-75, ISSN 2197-7410

- ↑ Hans-Peter Riese: Kasimir Malewitsch , p. 65 f, citation Haftmann p. 227 of the book edition

- ↑ Hans-Peter Riese: Kasimir Malewitsch , p. 127

- ↑ Gilles Néret: Malewitsch , pp. 76-80 ff

- ↑ Gilles Néret: Malewitsch , p. 89

- ↑ Hans-Peter Riese: Kasimir Malewitsch , p. 115

- ↑ Hans-Peter Riese: Kasimir Malewitsch , pp. 87, 130

- ↑ Kazimir Malevich: The white rectangle. Writings on the film. PotemkinPress, accessed June 30, 2008 .

- ↑ Gilles Néret: Malewitsch , p. 91

- ↑ From the Wikipedia article Suprematism

- ↑ Hans-Peter Riese: Kasimir Malewitsch , p. 61

- ↑ Hans-Peter Riese: Kasimir Malewitsch , p. 152

- ↑ Roland Enke: Malewitsch and Berlin - An Approach. In: db-artmag.com , 2003, accessed on April 16, 2015.

- ↑ Hans-Peter Riese: Kasimir Malewitsch , p. 153

- ↑ Hans-Peter Riese: The painter of the absolute. Andrei Nakov's impressive description of the work by Kasimir Malewitsch. ( Memento from October 22, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) In: FAZ , November 19, 2007.

- ^ Sebastian Egenhofer: Malewitsch: the late work. ( Memento from April 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) In: Universität Basel , 2006, accessed on April 16, 2015.

- ↑ Ira Mazzoni : Malevich and the consequences. In: db-artmag.com , 2003, accessed on April 16, 2015.

- ↑ Heiko Klaas: Brush art at zero. Spiegel Online, March 22, 2007, accessed June 27, 2008 .

- ↑ Belinda Grace Gardner: Don't be afraid of the black dice. Die Welt , March 17, 2007, accessed July 6, 2008 .

- ^ Petra Kipphoff : Black fabric. Die Zeit , March 29, 2007, accessed on July 27, 2008 .

- ^ Sebastian Preuss: The great utopia. In: Berliner Zeitung , November 3, 2004.

- ↑ Gilles Néret: Malewitsch , p. 7

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Malevich, Kazimir Severinovich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Малевич, Казимир Северинович (Russian) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian painter of cubo-futuristic painting and the founder of Suprematism |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 23, 1878 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Kiev |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 15, 1935 |

| Place of death | Leningrad |