Salzhaus (Frankfurt am Main)

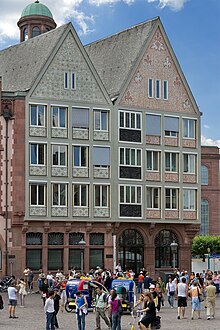

The Salzhaus is a historic building in Frankfurt am Main . It forms the northeastern part of the Frankfurt City Hall complex on the far right as seen from the Römerberg .

The salt house was originally built around 1600 with a richly carved facade on the gable side, making it not only the most important civil building in the city in terms of handicrafts, but also one of the greatest achievements of the Renaissance in the German-speaking area. In this form, the building was largely destroyed in a bomb attack in March 1944 . The base of the old building was retained, the floors above were built in 1951/52 in the simple architectural language of the post-war period . A reconstruction of the historical facade was discussed in the 1980s in the course of the reconstruction of the east line , but not carried out. Since then, the Friends of Frankfurt have taken on this topic.

While the gable of the salt house faces the Römerberg, the facade on the northern side of the eaves extends along Braubachstrasse , which separates the Römerberg from Paulsplatz . In the south, the building borders on Haus Frauenstein and in the west on Haus Wanebach , with which it has been connected internally since the 19th century . The house address is Römerberg 27 .

history

First mentioned until the 16th century

The first mention of the building goes back to a document dated May 5, 1324, according to which it, like the neighboring house, was owned by the noble Frankfurt patrician family Wanebach at that time . Although it is still popularly known as the Haus zum Hohen Homperg , a name whose etymology has not been fully clarified, it was also referred to as the salt house in various documents from the 14th century, which was derived from the salt trade that took place here .

The salt sale was a royal shelf , the so-called salt justice . It ensured the king high regular income. Through leasing or pledging , the salt shelf gradually passed to the city council, perhaps also directly into the hands of independent merchants. Proof that salt trade, in whatever form, has taken place in the house from the earliest times was the large stone basins integrated into the vaulted cellar of the house, which were still there in the early 20th century. Furthermore, the job title of the Selzer with a Werner Selzer next to the Römer is mentioned for the first time in 1300. Due to the growing size of the city, there were later other "salt houses" in Frankfurt, where this name never came into popular parlance, including the house for the pelican on the corner of the old town streets Kleiner Hirschgraben and Am Salzhaus .

It is likely that the parcel, commonly known as the salt house, had two independent, correspondingly very narrow half-timbered buildings until the early 17th century . This is shown by both pictures of the Römerberg from various older coronation diaries and the siege plan of the city by Conrad Faber from 1552, which shows two gables at the location of the building . However, due to its numerous inaccuracies, the plan is not very reliable historical evidence. Irrespective of this, the existence of two houses would be the most obvious explanation for the simultaneous mention of the Haus zum Hohen Homperg with the actual salt house.

Up to the end of the 16th century, there are only three documented messages that are of importance for the history of the building. In 1387, the salt house was owned by Gelnhausen's citizen Heinrich Bredemann , who sold it to a Wigand Dagestel on February 6 of the same year . Furthermore, in the years 1417 to 1423, the Society for the Golden Forge , first mentioned in 1407, met here , which got its name from the nearby parent company with the address Neue Kräme 17 . After 1423 they moved to the neighboring Frauenstein house. Here the Frauenstein Society developed into the second important patrician association in Frankfurt after the Alten Limpurg Society . Up until the early modern era, the Frauensteiners appointed the mayor of the city dozens of times.

Almost 40 years later, around 1460, the owner at the time, a Henne Brun , ran a private debt prison in the Salzhaus. At the request of the creditor , the city council detained defaulting debtors for up to 4 weeks, after which the creditor was allowed to continue to detain him until the debt was paid, albeit at his own expense. The private prisons, which were frequent in medieval Frankfurt and regulated by precise municipal regulations, were used for this purpose. The prison in the salt house was in the vaulted cellar, where a kind of cage had apparently been constructed with the help of wooden slats.

Mayor Koler's magnificent house

At the beginning of the 17th century the salt house was owned by Christoph Andreas Koler , who came from Bingen and had acquired a considerable fortune through the wine trade . Probably shortly after 1595 he had his house completely redesigned in the style of the late Renaissance , probably even completely rebuilt. This is confirmed by the close stylistic relationship with the nearby Silberberg House, dated 1595 , pictures from contemporary coronation diaries and, at the latest, the map of the town by Matthäus Merian from 1628, which shows the salt house as the sole building.

From then on, the salt house was considered to be one of the most beautiful buildings in Central Europe: on the one hand, the east facade of the building facing the Römerberg was presumably given holistic carved jewelry by the Memmingen sculptor Johann Michael Hocheisen , which remained very rare in the German Renaissance. The north facade facing the narrow Wedelgasse at that time , on the other hand, was plastered and decorated with frescoes that took up motifs from Greek mythology and the Bible .

The façade facing the Römerberg was also painted in the Frankfurt colors of red, white and gold, as a hand-colored copper engraving from the coronation diary of Joseph I from 1705 shows, and was also proven by the discovery of paint residues during the renovation of the building at the end of the 19th century . According to a legend, the wood turned black when Koler's wife died and the facade was traditionally hung with black cloths for the funeral procession. However, this contradicts the fact that his wife died in 1613. The real background for a possible deliberate leaching of the colors is most likely to be found in the classical efforts of the second half of the 18th century, when attempts were often made to give half-timbered buildings the appearance of stone buildings.

During the Fettmilch uprising , Koler joined the rebellious guilds and became the junior mayor in 1612. When in the course of 1614 the end of the uprising, in whose support he had lost almost all of his fortune, he fled the city and thus escaped punishment. In 1616 he finally went bankrupt and went back to his hometown, where he converted to the Catholic faith and worked as administrator of a monastery until his death.

After the Koler era until the 19th century

Little is known about the history of the salt house in the following two centuries. Due to its representative design, the spacious cellars, the availability of a shop on the ground floor and, last but not least, the optimal location on the Römerberg, it was almost exclusively owned by wealthy Frankfurt merchant families.

There is historical evidence that the rich silk and cloth merchant Melchior Sultzer died in the Salzhaus in 1637 , and that in 1718 Friedrich Freyer founded a hosiery shop in the house, which was the largest store of its kind in Frankfurt at the time. Due to his business success, he soon owned large workshops in Offenbach and Hanau, and when he died in 1752 he left his widow with an enormous fortune amounting to 212,000 Reichstalers.

City ownership and renovation

On May 1, 1843, the city bought the house for 32,000 guilders from its last owner, the citizen widow Sara Catharina Lindheimer . The long-established Lindheimer family was u. a. related to the Goethe family. Together with the adjacent Frauenstein house, which was acquired in the same year, the salt house was integrated into the building complex around the Römer . The demolition of the Haus zum Wedel in 1866 , which had flanked it to the north for centuries, also placed it in a new urban context when the once magnificently decorated north side became visible.

In the years 1887 to 1888, the renovation, which had meanwhile become urgently necessary, was tackled under the direction of city building inspector Adolf Koch . The modular construction of the oak panels on the first floor made it easy to remove them and take them to the workshops of joiners and sculptors , where they were painstakingly restored. It was found that during the previous renovation of the building, the gable inscription after 1707, damaged areas had been replaced with fir wood .

This procedure, which was later recognized as faulty, had further exacerbated the problem of the progressing rot in the wood and, from a static point of view, stressed the framework construction in the wrong places. The consequences, broken beams on the entire construction, had been counteracted by riveted metal strips or additional beams placed underneath. Load-bearing elements therefore had to be completely replaced in many places. At the places on the house where there was a loss of substance, this was filled with a putty made of oak chips and various admixtures and the corresponding parts were carved.

The frescoes on the north front of the building were so badly weathered at the time of the renovation work that it was decided not to restore them, but to replace them completely. After detailed sketches of the pictures had been made, the old plaster was removed and completely replaced. The new plaster was applied to a galvanized wire mesh stretched over the framework in order to prevent future weathering damage. Only after the plaster had dried for about a year from the summer of 1887 to 1888 and had proven its strength, were the previously documented pictures repainted using permanent mineral paints . Finally, the foliage surrounding the gable, of which little was left, was copied from the remains and completely replaced.

Around 1890, municipal employees moved into the salt house, which now shines again in its old splendor. Initially the military commission and parts of the statistical office were housed here, a little later the offices of the municipal health department.

The destruction in World War II

During the Second World War , it became apparent from July 1942 at the latest that Frankfurt would also become a target for heavy bombing raids. A large part of the historically significant buildings in Frankfurt's old town were then documented and immovable art monuments were walled in or relocated. This included all the removable relief panels of the salt house - only the carvings worked into the load-bearing beams of the actual half-timbered house had to remain on site.

The first heavy bombing raid hit the city center on October 5, 1943. Incendiary bombs devastated the interior of the Roman and the Citizens' Hall. The neighboring salt house was initially spared. On March 18, 1944, about 750 aircraft attacked the eastern city center. Again the salt house remained undamaged, although the Paulskirche on the opposite side of the street was hit and burned out completely.

The heaviest air raid hit the old town on March 22nd. More than seven thousand buildings were destroyed or badly damaged. The salt house was also hit by fire bombs and burned down. The entire interior was lost, only remnants of the stone basement remained.

Reconstruction and the present

In 1946, the rubble removal began in the old town. By 1950 the rubble and ruins had completely disappeared. It was not until 1952 that the building ban for the old town, which had been imposed in 1945, was lifted. In the meantime the decision had been made in favor of a modern reconstruction based on the ideas of urban planning at the time. In May 1952, work began to rebuild the old town, and in 1954 it was essentially complete.

Despite the rapid reconstruction, around 1950 there was a serious discussion about the pros and cons of a possible reconstruction of the salt house. Not insignificant parts of the carved facade had been saved, and the sources of the facade paintings on Braubachstrasse were comparatively good due to the restoration work that had only been carried out a few decades ago. On the other hand, there was an architectural body and also large parts of politics that were hostile to “historicism of a romantic kind” (Lord Mayor Kurt Blaum ), and there was still a great shortage of materials and finance.

The majority of the initially submitted designs envisaged simple and cheap cubist buildings for the salt house , which politicians decided against in January 1951 in favor of gabled structures in order to maintain the symmetry of the appearance towards the Römerberg. The dispute over a true-to-original reconstruction of the Roman complex lasted until May 1951, when the concept of the architects Otto Apel , Rudolf Letocha , William Rohrer and Martin Herdt was finally approved by the city council after a few changes.

The reconstruction of the old town, which was pursued without an overall plan and which has shaped the image of Frankfurt's inner city in large parts to this day, has mostly left behind simple functional buildings without any recognition value. In contrast, the “new salt house”, which was completed by autumn 1952, is one of the small number of buildings from the early 1950s that are to be regarded as artistic in-house achievements of a period primarily determined by material constraints. This group includes, for example, the Junior-Haus (1951) on Kaiserplatz , the Chemag-Haus (1952) in the Senckenberg-Anlage or the Rundschau-Haus (1953) on the corner of Große Eschenheimer Straße and Stiftstraße , with the latter In 2004 it was demolished despite the monument status .

However, even among these outstanding buildings, consideration for the history of the place is a rarity. This is not the case with the Salzhaus: The original ground floor taken over from the previous building, the spoils used in the new building , the traditional, slate-covered gable roof and the structure and scale of the reinforced concrete structure all cite the historical model. The ornamentation and the mural symbolizing the reconstruction of the city on the north side are considered to be an important new creation of the post-war period. The identity created in this way is also directly linked to the typical characteristics of the predominantly late Gothic Frankfurt old town houses, where each building could be identified as an individual despite its mostly simple exterior . The facade of the Roman complex with its five gables was therefore once again a symbol of Frankfurt after the reconstruction.

The original historical building has not disappeared from the collective memory of the city to this day. In the 1980s there were efforts in the citizenship to rebuild the salt house true to the original as part of the reconstruction of the east line of the Römerberg, which only failed because of lack of money.

An exhibition of the fragments in the Historisches Museum Frankfurt in December 2004 also showed that by no means as much building fabric was lost in the Second World War as generally assumed - around 60% of the facade is still stored intact in city magazines. In 2008, on the occasion of the planned reconstruction of some important Frankfurt town houses on the area of the Technical City Hall, which is to be demolished in 2009, the documentation Spolien der Frankfurt Altstadt was published. It also shows for the first time an inventory plan of the preserved facade parts of the salt house, which, according to the study, “are to be incorporated into the new building of the historical museum as outstanding spoils” .

At the beginning of July 2008, City Councilor Edwin Schwarz used the press to call on the population in and around Frankfurt to report possible privately owned Old Town Poles. In this context, the existence of another preserved original part of the salt house became known in May 2009. It is a carved oak molding with an egg bar profile that originally sat under the windows of the first floor.

Today the city's salt house serves as an administrative building. There is a tourist information center on the ground floor.

architecture

17th century to World War II

Stone ground floor

Like most of the buildings in what was once Frankfurt's old town , the salt house was built on a massive ground floor made of red Main sandstone . As the only part of the building that has been preserved almost entirely to the present day, it still reveals the mastery of Frankfurt's stonemasonry today . Another feature that the building has in common with other buildings in Frankfurt that fall into the style epoch and have largely disappeared (e.g. the Goldene Waage ) is the fact that the ground floor is broken up into arcades with richly decorated arches. In between, the statically significant pillars run up to the corbels on which the half-timbered upper floors originally rested.

On the east side of the building facing the Römerberg there are two arcade arches with three pillars, on the side facing Braubachstrasse and Paulsplatz there are five arcade arches with six pillars. The pillars are decorated with double rows of alternating high and flat diamond blocks ; the Attic profiling of the base , which can also be found on the capital , is continued into the inner surfaces. What is noticeable about the thin transom plate resting on the capital is that the diamond coating is also continued into the inner surfaces of the respective pillars.

The arches of the Römerberg Front, which stretch from fighter to fighter, are decorated on the inside with ornamental panels in tooth cut , followed by an egg stick on the outside; on the more simply designed north side there is only a tooth section profile to be seen. The skylights of the arched fields were once adorned with wrought-iron grilles made in through-work with elaborate ornamentation, which today appear in a greatly simplified form. In the absence of information, we can only assume that they were melted or irreparably damaged by falling parts of the building as a result of the immense heat that resulted from the burning down of the parts of the building above them in 1944.

The corbels also differ in their design on the east and north sides of the building, but not in their outstanding craftsmanship. On the north side there is a rectangular body under a profiled cover plate, in front of which a strong volute with lateral acanthus leaf decoration is placed, on the front side there is a human or a lion head ; underlaid by another volute console with its own cover plate. The east side of the Römerberg, on the other hand, has two corbels, where a quarter-circle body with a human head can be seen under a simple cover plate, which is built on a lower part with acanthus, tooth cut and fruit decorations. The very massive corner corbel, which is typical of the time, also makes use of the Renaissance canon of forms with its rich ornamental decoration , the remarkable upper area shows satyr masks between fruits. The latter repeat the motif of the grape over and over again , a clear reference to the suspected builder who had acquired his fortune through the wine trade .

The half-timbered building

The timber-framed part of the building rose above the stone ground floor in two upper floors cantilevered to the north and east and three gable floors above. The building was 22 m high from the ground floor to the gable, but measured at its widest point, i.e. at the level of the first floor on the east side facing the Römerberg, only 10 m. The fact that the roof construction alone made up almost half of the total height of the building emphasized the fact that, despite rich Renaissance decorations, the core was still late Gothic .

Since the demolition of the neighboring Haus zum Wedel in 1866, the building made a somewhat crooked impression. Objectively, this was due to the fact that the upper floors only protruded to the north, without compensation on the (built) southern side, and the overall construction had warped very little over the centuries. The apparent urban dependency on the neighboring house suggests that it was built at the same time, if not before. The detailed plan of the town by Matthäus Merian from 1628, in which the Haus zum Wedel cannot be seen, on the other hand, indicates that it was not built until the second third of the 17th century.

Facade to Braubachstrasse

On the northern long side facing the adjoining narrow Wedelgasse, or today Braubachstrasse, the timber of the framework remained without carving on both floors. Instead, the half-timbered character of the building was completely hidden under plaster, but no less richly decorated than the east facade in the form of frescoes . Between the single-colored pictures, which were applied in medallion-shaped fields and held in gray, the area was animated by painted festoons of flowers and fruits in red tones.

The actual construction showed the first floor seven and eleven right-justified window staggered arranged at regular intervals lugs beneath the overhanging threshold of the second floor. Here, as on the first floor, there were again seven windows, but shifted around an axis to the left. The first top floor was illuminated by five slightly larger, the two floors above with six small dormers each .

The arrangement of the pictorial representations, seen from the front, was as follows: one each to the left and right below the windows of the second floor, two to the left at the same height as the windows of the first floor, and below these two more left and two right. The frescoes showed motifs from Greek mythology as well as from the Aeneid of Virgil .

In detail, the motifs were in the order listed above:

- the sacrifice of Isaac when the angel was just bringing the divine message to Abraham ;

- Cain and Abel ;

- Galathea and Poseidon ;

- Endymion sleeping in the forest , whom Selene approaches to look at him;

- Heracles , the centaur Nessus killing;

- the liberation of Andromeda, forged on the rock, by Perseus ;

- Paris with the apple of Eris , about to judge the beauty of the three goddesses Hera , Athena and Aphrodite standing before him ;

- and finally the fire of Troy , in front of Aeneas , carrying his old father Anchises on his back, and his son Ascanius fleeing.

The mixing of Greek mythology with biblical motifs suggests that the former images were a bit older than the latter. Although not documented in the specific case of the salt house, but in comparable cases in the history of Frankfurt's building, the church or a later owner probably took offense at the purely pagan motifs. Accordingly, the two biblical motifs may have been added later.

This assumption is underpinned by the fact that the two biblical motifs were so high up on the building that they could hardly be seen from floor level in the narrow and dark Wedelgasse . It also contradicts the design principle that is otherwise followed on the house, especially the carved facade, to reduce the wealth of detail with increasing distance from the floor. However, the northern side of the house could only be seen in its original form again after the demolition of the Haus zum Wedel in 1866 and the reconstruction of its frescoes using preserved paint residues (see historical section).

Facade to the Römerberg

The narrow eastern side of the half-timbered section facing the Römerberg was holistically decorated with rich carvings. The structure of the first floor differed from the floors above. This was most evident through the six windows, which were not only irregularly spaced, but also came in three different sizes. In addition, the carving was hung in front of the actual construction and not, as in the other floors, worked as a carved filling into the seamlessly sculptured construction.

The window parapet was formed by a frieze with six wooden panels showing the following motifs from left to right: spring , summer , two putti with a ring (as a symbol of marriage), two putti with flowers (as a symbol of children), autumn and winter . Between the representations there were further panels with roller and fittings , as well as above between the windows. The panels that filled the slightly wider rooms on the far right and left of the storey were designed a little more elaborately. From human half-figures protruding foliage in rolled and fanned ends , rectangular framed by a scale ornament.

The northeast corner of the house was adorned with a female figure, which was attached to the upper half of the first floor and strongly resembled the figurehead of a ship from the time it was built. It was of the very highest quality and in its graceful forms can be attributed to the early 17th century, but the only element of the house was not made of oak , but carved from linden wood.

From the second floor, the carved facade appeared in a uniform design and, above all, symmetry up to the gable . In contrast to the previous floor, however, the carvings were not hung in front of the framework, but instead integrated directly into the facade. As the renovation of the building at the end of the 19th century showed, the compartments were traditionally filled with clay , but not plastered. Instead, it was filled with solid, 10 cm thick oak panels so that the entire facade was then presented in a uniform depth. Then the wooden surface, which was now uniformly divided into beams and compartments, was sculpted on site. The half-timbered structure of the building was shown here accordingly, which is seldom recognizable on old photos, especially since the facade was renovated, due to the excellent quality of the craftsmanship and the seamless execution of the carving work.

At the lower edge of the second floor there were two form boards covering the beam heads and the threshold, which were decorated with leaf tendrils and scrollwork. There were corner and center posts as well as the inner posts of the six windows, which were evenly distributed over the floor. The window sills each extended the full width of three windows and were only interrupted by the central mullion. The carvings on the aforementioned elements were mostly scrollwork, laurel rosettes and acanthus motifs ; scrollwork of antique vases rose in the narrow fields between the windows and the posts. Only the parapet areas also showed lion heads, diamond humps and the busts of the builder and his wife. These plastic elements were subsequently nailed to the oak panels.

A strong cornice , richly decorated with pearl rod , tooth cut, festoon frieze and scrollwork , separated the gable floor from the second floor. A wooden plaque with the inscription 1707 Renovatum was placed in the center of the cornice as a reference to a previous renovation . The cornice was in the shape of an inverted trapezoid so that its top outer ends protruded the full width of the building. In the course of the rising gable, this distinctive feature was repeated four times. The corner fields in between were steeply S-shaped and also decorated with scrollwork carvings.

Above each gable storey there was another tooth-cut profile, which followed the curved corner fields at the edge and rolled into a spiral in the lower area. Below the windows of the gable floors, as on the previous floors, there were ornate oak consoles with plastic diamond bosses or lions' heads; alternating scrollwork or beadwork carving on the posts between the windows. The holistic, magnificent appearance of the building was completed by a decorative strip cut out of sheet metal, gilded and drawn around the gable, which looked like a lace trim .

The differences between the first and the floors above have occasionally led to the assumption that the salt house was not a new building, but a conversion of one or more previous buildings. The reason given was the visibly more plastic, “ baroque ”-looking treatment of the first floor compared to the rest of the house, as well as its irregular window arrangement.

However, since the entire construction from the second floor was perfectly matched to the carved decorations, a later cladding of the ground floor would at most be considered, where the decorations were hung and thus theoretically could have been a later addition. Another indication of this is the discovery of remains of a painting under the paneling during the restoration in the 1880s. The close stylistic relationship of the storeys, despite the small differences, and the early absence of the client Koler made it impossible, if there were any, more than 10 years between two construction phases.

After the Second World War

The post-war "salt house" is a modern reinforced concrete building on the preserved ground floor of the previous building. Overall, the building has five floors, located on the ground floor, three upper floors and an attic within the provided with dormers and ver wrong Erten distribute gable roof.

In order not to disturb the proportions to the historical stone buildings of the Römerberg facade, the building, like the neighboring Frauenstein house from the same period, is almost the same height as the historical salt house. Its still very Gothic character - despite the rich Renaissance decorations - was lost during the reconstruction. In the historic Salzhaus, the roof took up almost half of the entire height of the eaves, in post-war construction it made up less than a third of the total height of the building. As the exterior view reveals, the proportions were changed to create another full storey.

The decoration of the building, however, is unusually rich for the time it was built. Below the windows, four on each floor and side of the house, there are limestone cladding , the eastern third of the side facing Braubachstrasse is covered by a glass mosaic by the artist Wilhelm Geißler that spans the three full floors . It is supposed to symbolize the spirit of optimism and optimism after the war and shows the motif of the phoenix rising from the ashes . With only a little imagination, one can also interpret the city's heraldic animal , which appears to rise from the ruins in the picture shown.

Finally, the six wooden relief panels by the sculptor Johann Michael Hocheisen from 1595 were incorporated into the new front on Römerberg instead of on the first floor of the original building. They are located in pairs below the southernmost or left-hand side of the house for the observer in front of it and still give a good impression of the high quality of the historic salt house.

Interior

As early as the 19th century, the interior of the house offered little that was exceptional; only a fireplace and an 18th century staircase decorated with carving and turning work remained of the original furnishings . When a fire wall was demolished , a Gothic mural was discovered during the renovation in the 1880s . It showed a female and male figure playing chess and a third male figure playing a stringed instrument. The picture was copied and then, because of its poor condition, it was not considered worth preserving, and it was torn down with the fire wall.

In the Second World War, the few pieces of equipment were finally destroyed during the reconstruction of the vaulted cellar, which was still reminiscent of the sale of salt. It was not until the exhibition about the salt house in 2004 that it became known that the war damage had revealed further Gothic murals on the rear gable. These too, which were particularly painful from an art-historical point of view, were removed in favor of the new building.

The interiors of the post-war building are designed in the simplest of functional forms and offer nothing remarkable.

Classification and comparable buildings

Carved decorations have been found on half-timbered buildings, especially in the Low German region, since the Gothic period. With the onset of the Renaissance, they spread to Central and Upper Germany from the 16th century onwards and reached a creative peak at the beginning of the 17th century.

While the centers in northern Germany were mainly in Braunschweig , Halberstadt and Hildesheim , the distribution area in southern Germany was mainly in the greater Middle Rhine area . Complete carved facades like that of the salt house are still a rarity even here. The reason for this is probably also primarily to be found in the Renaissance influences, which at the same time caused a slow turning away from half-timbered buildings as a residence in the sections of the population who could financially support such an elaborate design.

The Frankfurt Salt House was not only a rarity in the entire German half-timbered building, but especially for the city itself. The Gothic had a very long end in Frankfurt, which radiated into the early 18th century, the Renaissance was only very cautiously received and jewelry was frowned upon among the population. The few richly decorated half-timbered buildings came almost exclusively from immigrants, who therefore mostly had to deal with the conservative citizens.

Against this background, the emergence of the salt house in its representative form, which can hardly be increased, can be classified as an absolute rarity in Frankfurt's architectural history. The art historian Fried Lübbecke wrote in 1924 on the significance of this going beyond this : “[The] entire facade to the Römerberg, up to the gable, is covered with precious oak carvings. They belong to the technically and artistically most perfect of the entire German Renaissance. With the roughness of the late Gothic, the clarity of southern form is combined into a harmony that is rare in the north. "

In terms of quality, most comparable to the historic Salzhaus is the similarly splendidly redesigned Kammerzellhaus in Strasbourg in 1589 , which, in contrast, not only survived the Franco-German War , but also both world wars unscathed. However, its execution differs so much that it probably did not affect the style of the Frankfurt building. Also comparable is the Killingerhaus , built in Idstein im Taunus in 1615 , which has a carved facade of similar quality, but which is stylistically different and does not seem to follow an overall iconographic concept.

Only after the Thirty Years' War was the Krummel'sche Haus built in Wernigerode in 1674 , the structure and design of which is so clearly reminiscent of the Salzhaus that it was probably influenced by it. However, the building does not quite achieve the quality and size of the former model. Another example from the greater Harz area is the Eickesche Haus in Einbeck , built between 1612 and 1614 , whose rich carved facade, even if it does not extend over the entire house, follows a humanistic, overall concept and has an unusual quality for the size of the city. Structural relatives who are more or less distant can still be found in the entire area of distribution of the Low German half-timbering, despite enormous war losses. a. in Hildesheim and Braunschweig , as a reconstructed example in the former city is the Wedekindhaus from 1598.

literature

- Architects & Engineers Association (Ed.): Frankfurt am Main and its buildings . Self-published by the association, Frankfurt am Main 1886

- Johann Georg Battonn: Local Description of the City of Frankfurt am Main - Volume IV . Association for history and antiquity in Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 1866, pp. 142–143

- Hartwig Beseler, Niels Gutschow: War fates of German architecture - losses, damage, reconstruction - Volume 2, south . Karl Wachholtz Verlag, Neumünster 1988, p. 812

- Georg Hartmann, Fried Lübbecke (Ed.): Alt-Frankfurt. A legacy . Verlag Sauer and Auvermann, Glashütten 1971, pp. 72-77

- Hermann Heimpel: The salt house on the Römerberg . In: Frankfurter Verkehrsverein (Ed.): Frankfurter Wochenschau . Bodet & Link, Frankfurt am Main 1939, pp. 152–156

- Historical museum presents the art of carving from the “salt house” . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine: Zeitung for Germany (ed.), Frankfurt am Main November 9, 2004

- Walter Sage: The community center in Frankfurt a. M. until the end of the Thirty Years War. Wasmuth, Tübingen 1959 ( Das Deutsche Bürgerhaus 2), pp. 96–99

- Carl Wolff, Rudolf Jung: The architectural monuments of Frankfurt am Main - Volume 2, secular buildings . Self-published / Völcker, Frankfurt am Main 1898, pp. 239–245

Remarks

- ^ Project Salzhaus: Friends of Frankfurt , accessed on September 28, 2016

- ↑ Printed in full length by Johann Friedrich Boehmer, Friedrich Lau: Urkundenbuch der Reichsstadt Frankfurt . Volume II 1314-1340. J. Baer & Co, Frankfurt am Main 1901–1905, pp. 194, 195, certificate no. 251

- ↑ Documented reports of how the salt shelf came to the city from the king have not survived. According to Fried Lübbecke (in: Alt-Frankfurt. Ein Vermächtnis . Verlag Sauer and Auvermann, Glashütten 1971, p. 73) it was leased or pledged to the council, according to the monograph by Hermann Heimpel (in: Das Salzhaus am Römerberg . In : Frankfurter Verkehrsverein (Ed.): Frankfurter Wochenschau . Bodet & Link, Frankfurt am Main 1939, p. 152) the salt trade in Frankfurt was never a municipal monopoly, but was operated by independent merchants who, however, had to pay a special salt tax to the council .

- ^ Karl books: The professions of the city of Frankfurt a. M. in the Middle Ages . BG Teubner, Leipzig 1914, p. 112

- ^ A b c Carl Wolff, Rudolf Jung: The architectural monuments of Frankfurt am Main - Volume 2, secular buildings . Self-published / Völcker, Frankfurt am Main 1898, p. 239

- ↑ Johann Georg Battonn: Slave Narratives Frankfurt - Volume IV . Association for history and antiquity in Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 1866, p. 143

- ^ Hermann Heimpel: The salt house on the Römerberg . In: Frankfurter Verkehrsverein (Ed.): Frankfurter Wochenschau . Bodet & Link, Frankfurt am Main 1939, pp. 152, 153

- ↑ a b c d Hermann Heimpel: The salt house on the Römerberg . In: Frankfurter Verkehrsverein (Ed.): Frankfurter Wochenschau . Bodet & Link, Frankfurt am Main 1939, p. 153

- ^ Fried Lübbecke: Alt-Frankfurt. A legacy . Verlag Sauer and Auvermann, Glashütten 1971, pp. 73, 74

- ^ A b Walter Sage: The community center in Frankfurt a. M. until the end of the Thirty Years War. Wasmuth, Tübingen 1959 ( Das Deutsche Bürgerhaus 2), p. 99

- ^ A b c d Frankfurter Allgemeine: Newspaper for Germany , November 9, 2004, Rhein-Main-Zeitung

- ^ Carl Wolff, Rudolf Jung: The architectural monuments of Frankfurt am Main - Volume 2, Secular buildings . Self-published / Völcker, Frankfurt am Main 1898, p. 240

- ^ Fried Lübbecke: Alt-Frankfurt. A legacy . Verlag Sauer and Auvermann, Glashütten 1971, p. 76

- ↑ Purchase contract at the Institute for Urban History in Frankfurt am Main, inventory of house documents, signature 1.795

- ^ Carl Wolff, Rudolf Jung: The architectural monuments of Frankfurt am Main - Volume 2, Secular buildings . Self-published / Völcker, Frankfurt am Main 1898, p. 244

- ^ Carl Wolff, Rudolf Jung: The architectural monuments of Frankfurt am Main - Volume 2, Secular buildings . Self-published / Völcker, Frankfurt am Main 1898, p. 238

- ↑ according to plans by Carl Wolff, Rudolf Jung: Die Baudenkmäler von Frankfurt am Main - Volume 2, Secular Buildings . Selbstverlag / Völcker, Frankfurt am Main 1898, pp. 239–245 and contemporary address books

- ^ Hartwig Beseler, Niels Gutschow: Kriegsschicksale Deutscher Architektur. Loss, damage, rebuilding. Volume II: Süd, Karl Wachholtz Verlag, Neumünster 1988, p. 812

- ^ A b Hermann Meinert, Theo Derlam: Das Frankfurter Rathaus. Its history and its reconstruction . Waldemar Kramer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1952, p. 34

- ^ Hartwig Beseler, Niels Gutschow: Kriegsschicksale Deutscher Architektur. Loss, damage, rebuilding. Volume I: Nord, Karl Wachholtz Verlag, Neumünster 1988, p. LII

- ↑ Wolfgang Dreysse, Björn Wissenbach: Planning area - Dom Römer. Spolia of the old town 1. Documentation of the original components of Frankfurt town houses stored in the Historical Museum . Urban Planning Office, Frankfurt am Main 2008, p. 7.

- ↑ Wolfgang Dreysse, Björn Wissenbach: Planning area - Dom Römer. Spolia of the old town 2. Spolia in private ownership. Documentation of the privately owned original components of Frankfurt town houses . Urban Planning Office, Frankfurt am Main 2008, p. 101.

- ^ Hermann Heimpel: The salt house on the Römerberg . In: Frankfurter Verkehrsverein (Ed.): Frankfurter Wochenschau . Bodet & Link, Frankfurt am Main 1939, p. 156

- ↑ There was never so much goodbye in FAZ on September 27, 2014, page B6

- ^ Carl Wolff, Rudolf Jung: The architectural monuments of Frankfurt am Main - Volume 2, Secular buildings . Self-published / Völcker, Frankfurt am Main 1898, pp. 244, 245

- ^ Fried Lübbecke, Paul Wolff (Ill.): Alt-Frankfurt. New episode. Verlag Englert & Schlosser, Frankfurt am Main 1924, pp. 26, 27

Web links

- The salt house. altfrankfurt.com

- Frankfurt am Main in the air war

- View from the cathedral to the destroyed Römerberg , color photographs by Paul Wolff in the summer of 1944

- Reconstruction of the old town in 1952 ( Memento from June 17, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- FAZ article with u. a. new facts about the actual preservation of the salt house

- State Office for Monument Preservation Hesse (ed.): Römer / Altes Rathaus, Salzhaus und Haus Frauenstein In: DenkXweb, online edition of cultural monuments in Hesse

Coordinates: 50 ° 6 ′ 39 ″ N , 8 ° 40 ′ 55 ″ E