Nomadic empire: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 161: | Line 161: | ||

==[[Timurid Empire]]== |

==[[Timurid Empire]]== |

||

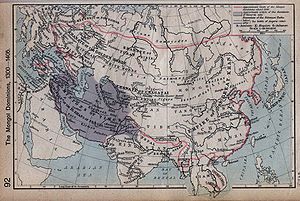

[[Image:Mongol dominions.jpg|thumb|300px|Timurid continental map]] |

|||

The '''[[Timurids]]''' ({{PerB|تیموریان}} - ''Tīmūrīyān''), self-designated '''Gurkānī''' ({{PerB|گوركانى}}) <span dir="ltr"> <ref name="baburnama">{{cite book | title=The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor |publisher=Modern Library Classics |id=ISBN 0375761373 |year=2002 |date=[[2002-09-10]] |author=Zahir ud-Din Mohammad |editor=Thackston, Wheeler M. |accessdate=2006-11-10}}</ref><ref>Note: ''Gurkānī'' is the [[Persianization|Persianized]] form of the Mongolian word ''kürügän'' [''"son-in-law"''], the title given to the dynasty's founder after his marriage into [[Genghis Khan]]'s family <small>(Thackston, Wheeler M. ''The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor''. Modern Library Classics. ISBN 0375761373)</small></ref></span>, were a [[Islam|Muslim]] dynasty of originally [[Mongols|Mongolian]]<ref name="EI">B.F. Manz, ''"Tīmūr Lang"'', in [[Encyclopaedia of Islam]], Online Edition, 2006</ref><ref>''"Timur"'', The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001-05 Columbia University Press, ([http://www.bartleby.com/65/ti/Timur.html LINK])</ref><ref>"Consolidation & expansion of the Indo-Timurids", in [[Encyclopaedia Britannica]], ([http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-26937/Islamic-world LINK])</ref> descent, established by the [[Central Asia]]n warlord [[Timur]]. At its zenith, the Timurid Empire included the whole of [[Central Asia]], [[Iran]] and modern [[Afghanistan]], as well as large parts of [[Mesopotamia]] and [[Caucasus]]. |

|||

In the [[16th century]], Timurid prince [[Babur|Zahir ud-Din Babur]], the ruler of [[Ferghana]], invaded [[India]] and founded the [[Mughal Empire]] - the ''Timurids of India'' - who ruled most of the [[Indian subcontinent]] for several centuries until the [[British Raj|British conquest of India]]. The Mughal empire is not considered a classic horse archer empire but rather an empire founded by peoples previously from the horse arhcer civilization, much like the [[Parthian empire]] |

|||

== History == |

|||

[[Image:Timurid.png|thumb|150px|right|Flag of the Timurid Empire according to the Catalan Atlas c.1375]] |

|||

Timur conquered large parts of [[Transoxiana]] (in modern day Central Asia) and [[Greater Khorasan|Khorasan]] (in modern day [[Iran]] and [[Afghanistan]]) from [[1363]] onwards with various alliances ([[Samarqand]] in [[1366]], and [[Balkh]] in [[1369]]), and was recognized as ruler over them in [[1370]]. Acting officially in the name of the Mongolian [[Chagatai Khanate|Chagatai ulus]], he subjugated [[Transoxania]] and [[Khwarazm]] in the years that followed and began a campaign westwards in [[1380]]. By [[1389]] he had removed the Kartids from [[Herat]] and advanced into mainland [[Persian Empire|Persia]] from [[1382]] (capture of [[Isfahan (city)|Isfahan]] in [[1387]], removal of the Muzaffarids from [[Shiraz, Iran|Shiraz]] in [[1393]], and expulsion of the Jalayirids from [[Baghdad]]). In [[1394]]/[[1396|95]] he triumphed over the [[Golden Horde]] and enforced his sovereignty in the [[Caucasus]], in [[1398]] subjugated what is today [[Pakistan]] and northern [[India]] and occupied [[Delhi]], in [[1400]]/[[1401|01]] conquered [[Aleppo]], [[Damascus]] and eastern Anatolia, in 1401 destroyed Baghdad and in [[1402]] triumphed over the Ottomans at [[Ankara]]. In addition, he transformed Samarqand into the ''Center of the World''. |

|||

After the end of the [[Timurid Empire]] in [[1506]], the [[Mughal Empire]] was later established in India by [[Babur]] in [[1526]], who was a descendant of [[Timur]] through his father and possibly a descendant of [[Genghis Khan]] through his mother. The dynasty he established is commonly known as the [[Mughal Dynasty]]. By the [[17th century]], the Mughal Empire ruled most of India, but later declined during the [[18th century]]. The Timurid Dynasty came to an end in [[1857]] after the Mughal Empire was dissolved by the [[British Empire]] and [[Bahadur Shah II]] was exiled to [[Burma]]. |

|||

The Timurids made [[Herat]] and [[Samarqand]] their capitals. It is believed that the period of Timurids resembles to a [[Renaissance|Renaissance Age]] for [[Greater Khorasan|Khorasan]]. |

|||

==References and notes== |

==References and notes== |

||

| Line 179: | Line 192: | ||

* Sinor, Denis, "The Inner Asian Warrior," in Denis Sinor, (Collected Studies Series), Studies in Medieval Inner Asia, Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate, Variorum, 1997, XIII. |

* Sinor, Denis, "The Inner Asian Warrior," in Denis Sinor, (Collected Studies Series), Studies in Medieval Inner Asia, Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate, Variorum, 1997, XIII. |

||

* Sinor, Denis, "Horse and Pasture in Inner Asian History," in Denis Sinor, (Collected Studies Series), Inner Asia and its Contacts with Medieval Europe, London: Variorum, 1977, II. |

* Sinor, Denis, "Horse and Pasture in Inner Asian History," in Denis Sinor, (Collected Studies Series), Inner Asia and its Contacts with Medieval Europe, London: Variorum, 1977, II. |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 18:08, 1 February 2007

Horse archer empires is the term used to describe the empires erected by Eurasian nomads. Not all horse archer civilizations were able do erect empires. Fearsome warrior peoples like the Avars and Magyars have conquered vast areas and founded kingdoms but did not subjugated other nations to be considered as empires.

Hunnic Empire

The Huns were a confederation of Eurasian tribes from the Steppes of Central Asia. Through a combination of advanced weaponry, amazing mobility and battlefield tactics, they achieved military superiority over many of their largest rivals, subjugating the tribes they conquered.[1] Appearing from beyond the Volga River some years after the middle of the 4th century, they first overran the Alani, who occupied the plains between the Volga and the Don rivers, and then quickly overthrew the empire of the Ostrogoths between the Don and the Dniester. About 376 they defeated the Visigoths living in what is now approximately Romania and thus arrived at the Danubian frontier of the Roman Empire.[2] Their mass migration into Europe brought with it great ethnic and political upheaval.

Origins

The origins of the Huns that swept through Europe during the 4th Century remain unclear. However, mainstream historians consider them as a group of nomadic tribes from Central Asia probably ruled by a Turkic-speaking aristocracy. The Huns were probably ethnically diverse, due to the various cultures brought under their subjugation.

Early Campaigns

Ancient accounts suggest that the Huns had settled in the lands north-west of the Caspian Sea as early as the 3rd Century. By the latter half of the century, about 370, the Caspian Huns mobilized, destroying a tribe of Alans to their west. Pushing further westward the Huns ravaged and destroyed an Ostrogothic kingdom. In 395, a Hun raid across the Caucasus mountains devastated Armenia, there they captured Erzurum, besieged Edessa and Antioch, even reaching Tyre in Syria.

In 408, the Hun Uldin invaded the Eastern Roman province of Moesia but his attack was checked and Uldin was forced to retreat.

Consolidation

For all their early exploits, the Huns were still politically too disunited to stage a serious campaign. Rather than an empire the Huns were rather a confederation of kings. Although there was the title of 'High King', very few of those bearing this title managed to rule effectively over all the Hunnic tribes. As a result, the Huns were without clear leadership and lacked any common objectives.

From 420, a chieftain named Oktar began to weld the disparate Hunnic tribes under his banner. He was succeeded by his brother, Rugila who became the leader of the Hun confederation, uniting the Huns into a cohesive group with a common purpose. He lead them into a campaign in the Western Roman Empire, through an alliance with Roman General Aetius. This gave the Huns even more notoriety and power. He planned a massive invasion of the Eastern Roman Empire in the year 434, but died before his plans could come to fruition. His heirs to the throne were his nephews, Bleda and Attila, who ruled in a dual kingship. They divided the Hunnic lands between them, but still regarded the empire as a single entity.

Under the Dual Kingship

Attila and Bleda were as ambitious as king Ruga. They forced the Eastern Roman Empire to sign the Treaty of Margus, giving the Huns (amongst other things) trade rights and an annual tribute from the Romans. With their southern border protected by the terms of this treaty, the Huns could turn their full attention to the further subjugation of tribes to the east.

However, when the Romans failed to deliver the agreed tribute, and other conditions of the Treaty of Margus were not met, both the Hunnic kings turned their attention back to the Eastern Romans. Reports that the Bishop of Margus had crossed into Hun lands and desecrated royal graves further incensed the kings. War broke out between the two empires, and the Huns capitalized on a weak Roman army to raze the cities of Margus, Singidunum and Viminacium. Although a truce was signed in 441, war resumed two years later with another failure by the Romans to deliver the tribute. In the following campaign, Hun armies came alarmingly close to Constantinople, sacking Sardica, Arcadiopolis and Philippopolis along the way. Suffering a complete defeat at the Battle of Chersonesus, the Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II gave in to Hun demands and the Peace of Anatolius was signed in autumn 443. The Huns returned to their lands with a vast train full of plunder.

In 445, Bleda died, leaving Attila the sole ruler of the Hun Empire.

As Attila's Empire

With his brother gone and as the only ruler of the united Huns, Attila possessed undisputed control over his subjects. In 447, Attila turned the Huns back toward the Eastern Roman Empire once more. His invasion of the Balkans and Thrace was devastating, with one source citing that the Huns razed 70 cities. The Eastern Roman Empire was already beset from internal problems, such as famine and plague, as well as riots and a series of earthquakes in Constantinople itself. Only a last-minute rebuilding of its walls had protected Constantinople unscathed. Victory over a Roman army had already left the Huns virtually unchallenged in Eastern Roman lands and only disease forced a retreat, after they had conducted raids as far south as Thermopylae.

The war finally came to an end for the Eastern Romans in 449 with the signing of the Third Peace of Anatolius.

Throughout their raids on the Eastern Roman Empire, the Huns had still maintained good relations with the Western Empire, this was due in no small part to a friendship with Aetius, a powerful Roman general (sometimes even referred to as the defacto ruler of the Western Empire) who had spent some time with the Huns. However, this all changed when Honoria, sister of the Western Roman Emperor Valentinian III, sent Attila a ring and requested for his help to escape her betrothal to a senator. Although it is not known whether Honoria intended this as a proposal of marriage to Attila, that is how the Hun King interpreted it. He claimed half the Western Roman Empire as dowry. To add to the failing relations, a dispute between Attila and Aetius about the rightful heir as king of the Salian Franks also occurred. Finally, the repeated raids on the Eastern Roman Empire had left it with little to plunder.

In 451, Attila's forces entered Gaul, with his army recruiting from the Franks, Goths and Burgundian tribes they passed en route. Once in Gaul, the Huns first attacked Metz, then his armies continued westwards, passed both Paris and Troyes to lay siege to Orleans.

Aetius was given the duty of relieving Orleans by Emperor Valentinian III. Bolstered by Frankish and Visigothic troops (under King Theodoric), Aetius' own Roman army met the Huns at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields. Although inconclusive, the battle thwarted Attila's invasion of Gaul, and forced his retreat back to Hunnic lands.

The following year, Attila renewed his claims to Honoria and territory in the Western Roman Empire. Leading his horde across the Alps and into Northern Italy, he sacked and razed the cities of Aquileia, Vicetia, Verona, Brixia, Bergomum, and Milan. Finally, at the very gates of Rome, he turned his army back. The reason for this is still a mystery. It might have been due to an epidemic in Hun ranks, or perhaps a renewed threat from the Eastern Roman Empire. Whatever the cause, Attila retreated back to Hunnic lands without Honoria or her dowry.

From the Carpathian Basin, Attila mobilised to attack Constantinople, in retaliation for the new Eastern Roman Emperor Marcian halting tribute payments. Before this planned attack he married a German girl named Ildiko. In 453, he died of a nosebleed on his wedding night.

After Attila

Attila was succeeded by his eldest son, Ellak. However, Attila's other sons, Dengizich and Ernakh challenged Ellak for the throne. Taking advantage of the siutation, subjugated tribes rose up in rebellions. The Huns were defeated in the Battle of Nedao. In 469, Dengizik, the last Hunnic King and successor of Ellak, died. This date is seen as the end of the Hunnic Empire. It is believed that some of Attila's Huns in South-East Europe continued ruling over lands there, forming the Bulgarian Empire, which stretched over the Balkans, Pannonia and Scythia.

Göktürk Empire

The Göktürks or Kök-Türks were a Turkic people of ancient North and Central Asia, Eastern Europe and northwestern China. Known in medieval Chinese sources as Tujue (突厥 Tū jué), the Göktürks under the leadership of Bumin/Tuman Khan/Khaghan (d. 552) and his sons, established the first known Turkic state around 552 in the general area of territory that had earlier been occupied by the Huns, and expanded rapidly to rule wide territories in Central Asia. The Göktürks originated from the Ashina tribe, an Altaic people who lived in the northern corner of the area presently called the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China. They were the first Turkic tribe to use the name "Türk" as a political name.

First unified empire

The Turks' rise to power began in 546 when Tumen made a pre-emptive strike against the Tiele tribes who were planning a revolt against their overlords, the Rouran. For this service he expected to be rewared with a Rouran princess, i.e. marry into the royal family. But there was to be no princess. Enraged, Tumem allied with the Wei state against Rouran, their common enemy. In 552, Tuman defeated the last Rouran Khan, Yujiulü Anagui. He was formally recognized by China, and married the Wei princess Changle. Thus proving himself both in battle and diplomacy he declared himself Il-Qaghan (great king of kings) of the new Göktürk empire at Otukan, the old Xiongnu capital. He died one year later; the Göktürk state was really built by his son Mukhan. Tuman's brother Istämi (d. 576) was titled yabghu of the west and collaborated with the Persian Sassanids to defeat and destroy the White Huns, who were allies of the Rouran. This war drove the Avars into Europe. Istämi initiated diplomatic contact with the Byzantine Empire, and together they built an alliance against the Persians. Both rival states in north China paid large tributes to the Göktürks from 581.

Alliance

The Göktürk Empire continued extremely close ties with the Goguryeo Dynasty of Manchuria and the northern part of the Korean Peninsula. Giving gifts, providing military support, and free trade were some of the benefits of this close mutual alliance. The most significant incident is of the Goguryeo-Sui and Goguryeo-Tang wars, where the Sui and later Tang dynasties of China invaded Goguryeo. The Sui dynasty was annihilated in their invasion by defending Goguryeo troops. Though weaker, the Tang Dynasty was able to overcome Goguryeo with the help of a neighboring Korean state, Shilla, and mark its fall. In this war, the Göktürks opened a second front on the western Chinese border to help ease Goguryeo's plight.

Civil war

This first Göktürk Empire split in two after the death of the fourth Qaghan, Taspar Khan (ca. 584). He had willed the title Qaghan to Mukhan's son Talopien, but the high council appointed Ishbara. Factions formed around both leaders. Soon, four rival khans claimed the title Qaghan. They were successfully played off against each other by Sui and Tang Dynasty China. The most serious contender was the Western Khan, Istämi's son Tardu, a violent and ambitious man who had already declared himself independent of the Qaghan after his father's death. He now titled himself as Qaghan (Khagan) the supreme ruler, and lead an army to the east to claim Otukan. Ishbara, Khan of the Eastern Khanate fearing defeat became formally subordinate to the Chinese Emperor Yangdi for protection. Tardu attacked Changan the Sui capital around 600 as a warning to Emperor Yangdi to end his interference in the civil war. However, Chinese diplomacy incited a revolt of Tardu's Tiele vassal tribes, and Tardu's reign was cut short in 603. Among the dissident tribes were the Uyghur and Syr-Tardush.

Dual empires

The civil war left the empire divided into an east and west. The east retained the name Göktürk as vassals of the Sui Empire, and the newly independent Western Turkic Khaganate was called Onoq (ten arrows)[citation needed]. Khan Hsien of the East attacked China at its weakest moment during the transition between Sui and Tang dynasties. He was brought down by a revolt of his Tiele vassal tribes (626-630), allied with Emperor Taizong of Tang. This tribal alliance is recorded as the Huihe (Uyghur). The Khan was taken prisoner and his empire was zoned into protectorates by the Tang dynasty. The Western Khan Tung Sche-hu was murdered in 630 by Persian diplomacy, despite strong support by the Byzantine Empire against the Persians. The Onoq were divided into east and west factions called Tulu and Nushipi respectively[citation needed]. They were conquered by the Tang general Su Ding Fang in 657. By 659 the Tang Emperor of China could claim to rule the entire Silk Road as far as Po-sse (Persia). The Turks now carried Chinese titles and fought by their side in their wars.

Inter-imperial era

The era spanning from 659-681 was characterized by numerous independent rulers weak divided and engaged in constant petty wars. In the east, the Uyghurs defeated their one time allies the Tardush, while in the west, the Turgish emerged as successors to the Onoq.

Second empire

Nonetheless, Ilteriş Şad (Idat) and his brother Bäkçor Qapağan Khan (Mo-ch'o) managed to refound the Khanate which in a series of wars from 681 onward gained control of the steppes beyond the Great Wall of China, extending by 705 to threaten Arab control of Transoxiana. Their power centered at the Changai Mountains (then: Ötükän). The son of Ilteriş, Bilge, was also a strong leader, but at his death in 734, the empire declined. They ultimately fell to a series of internal crises and renewed Chinese campaigns. After Kutluk (Ko-lo) Khan's military victory in 744, the successors to the Göktürks became their more China-friendly junior partners, known as the Uyghurs.

Uyghur Empire

Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire (Mongolian: Их Монгол Улс, meaning "Greater Mongol Nation"; 1206–1405) was the largest contiguous land empire in history, covering over 33 million km² [3] at its peak, with an estimated population of over 100 million people. The Mongol Empire was founded by Genghis Khan in 1206, and at its height, it encompassed the majority of the territories from southeast Asia to central Europe.

After unifying the Mongol–Turkic tribes, the Empire expanded through numerous conquests throughout continental Eurasia starting with the conquests of Western Xia in north China and Khwarezmid Empire in Iran. Modern estimates suggest that as many as 30 million people died during the Mongol conquests.

During its existence, the Pax Mongolica facilitated cultural exchange and trade between the East, West, and the Middle East in the period of the 13th and 14th centuries.

The Mongol Empire was ruled by the Khagan. After the death of Möngke Khan, it split into four parts (Yuan Dynasty, Il-Khans, Chagatai Khanate and Golden Horde), each of which was ruled by its own Khan.

Genghis Khan and the formation of the Mongol empire

Genghis Khan, through political manipulation and military might, united the nomadic, previously ever-rivalling Mongol-Turkic tribes under his rule by 1206. He quickly came into conflict with the Jin Dynasty empire of the Jurchen and the Western Xia in northern China. Under the provocation of the Muslim Khwarezmid Empire, he moved into Central Asia as well, devastating Transoxiana and eastern Persia, then raiding into Kievan Rus' (a predecessor state of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine) and the Caucasus. While engaged in a final war against the Western Xia, Genghis fell ill and died. Before dying, Genghis Khan divided his empire among his sons and immediate family, but as custom made clear, it remained the joint property of the entire imperial family who, along with the Mongol aristocracy, constituted the ruling class.

Major events in the Early Mongol Empire

- 1206: By this year, Temujin from the Orkhon Valley dominated Mongolia and received the title Genghis Khan, thought to mean Oceanic Ruler or Firm, Resolute Ruler

- 1207: The Mongols began operations against the Western Xia, which comprised much of northwestern China and parts of Tibet. This campaign lasted until 1210 with the Western Xia ruler submitting to Genghis Khan. During this period, the Uyghur Turks also submitted peacefully to the Mongols and became valued administrators throughout the empire.

- 1211: After a great quriltai or meeting, Genghis Khan led his armies against the Jin Dynasty that ruled northern China.

- 1218: The Mongols capture Semirechye and the Tarim Basin, occupying Kashgar.

- 1218: The execution of Mongol envoys by the Khwarezmian Shah Muhammad sets in motion the first Mongol westward thrust.

- 1219: The Mongols cross the Jaxartes (Syr Darya) and begin their invasion of Transoxiana.

- 1219–1221: While the campaign in northern China was still in progress, the Mongols waged a war in central Asia and destroyed the Khwarezmid Empire. One notable feature was that the campaign was launched from several directions at once. In addition, it was notable for special units assigned by Ghenghis Khan personally to find and kill Ala al-Din Muhammad II, the Khwarazmshah who fled from them, and ultimately ended up hiding on an island in the Caspian Sea.

- 1223: The Mongols gain a decisive victory at the Battle of the Kalka River, the first engagement between the Mongols and the East Slavic warriors.

- 1226: Invasion of the Western Xia, being the second battle with the Western Xia.

- 1237: Under the leadership of Batu Khan, the Mongols return to the West and begin their campaign to subjugate Kievan Rus'.

After Genghis Khan

At first, the Mongol Empire was ruled by Ogedei Khan, Genghis Khan's third son and designated heir, but after his death in 1241, the fractures which would ultimately crack the Empire began to show. Enmity between the grandchildren of Genghis Khan resulted in a five year regency by Ogedei's widow until she finally got her son Guyuk Khan confirmed as Great Khan. But he only ruled two years, and following his death --he was on his way to confront his cousin Batu Khan, who had never accepted his authority-- another regency followed, until finally a period of stability came with the reign of Monke Khan, from 1251-1259. The last universally accepted Great Khan was his brother Kublai Khan, from 1260-1294. Despite his recognition as Great Khan, he was unable to keep his brother Hulagu and their cousin Berke from open warfare in 1263, and after Kublai's death, there was not an accepted Great Khan, so the Mongol Empire was fragmented for good.

The following Khanates emerged since the regency following Ogedei Khan's death, up to the reign of Kublai Khan, and became formally independent after his death with Great Khan overseeing them and has ultimate reign over as a single entity until after death of Khublai Khan. Genghis Khan divided the empire into four Khanates, sub-rules, but as a single empire under the Great Khan (Khan of Khans).

- Blue Horde (under Batu Khan) and White Horde (under Orda Khan) would soon be combined into the Golden Horde, with Batu Khan emerging as Khan.

- Il-Khanate - Hulegu Khan

- Empire of the Great Khan (China) - Kublai Khan

- Mongol homeland (present day Mongolia, including Kharakhorum) - Tolui Khan

- Chagadai Khanate - Chagatai Khan

The empire's expansion continued for a generation or more after Genghis's death in 1227. Under Genghis's successor Ögedei Khan, the speed of expansion reached its peak. Mongol armies pushed into Persia, finished off the Xia and the remnants of the Khwarezmids, and came into conflict with the Song Dynasty of China, starting a war that would last until 1279 concluding with the Mongols' successful conquest of populous China, which constituted then the majority of the world's economic production.

Then, in the late 1230s, the Mongols under Batu Khan invaded Russia and Volga Bulgaria, reducing most of its principalities to vassalage, and pressed on into Eastern Europe. In 1241 the Mongols may have been ready to invade western Europe as well, having defeated the last Polish-German and Hungarian armies at the Battle of Legnica and the Battle of Mohi. Batu Khan and Subutai were preparing to invade western Europe, starting with a winter campaign against Austria and Germany, and finishing with Italy. However news of Ögedei's death prevented any invasion as Batu had to turn his attentions to the election of the next great Khan. It is often speculated that this was one of the great turning points in history and that Europe may well have fallen to the Mongols had the invasion gone ahead.

During the 1250s, Genghis's grandson Hulegu Khan, operating from the Mongol base in Persia, destroyed the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad and destroyed the cult of the Assassins, moving into Palestine towards Egypt. The Great Khan Möngke having died, however, he hastened to return for the election, and the force that remained in Palestine was destroyed by the Mamluks under Baibars in 1261 at Ayn Jalut.

Disintegration

When Genghis Khan died, a major potential weakness of the system he had set up manifested itself. It took many months to summon the kurultai, as many of its most important members were leading military campaigns thousands of miles from the Mongol heartland. And then it took months more for the kurultai to come to the decision that had been almost inevitable from the start — that Genghis's choice as successor, his third son Ögedei, should become Great Khan. Ögedei was a rather passive ruler and personally self-indulgent, but he was intelligent, charming and a good decision-maker whose authority was respected throughout his reign by apparently stronger-willed relatives and generals whom he had inherited from Genghis.

On Ögedei's death in 1241, however, the system started falling apart. Pending a kurultai to elect Ögedei's successor, his widow Toregene Khatun assumed power and proceeded to ensure the election of her son Guyuk by the kurultai. Batu was unwilling to accept Guyuk as Great Khan, but lacked the influence in the kurultai to procure his own election. Therefore, while moving no further west, he simultaneously insisted that the situation in Europe was too precarious for him to come east and that he could not accept the result of any kurultai held in his absence. The resulting stalemate lasted four years. In 1246 Batu eventually agreed to send a representative to the kurultai but never acknowledged the resulting election of Guyuk as Great Khan.

Guyuk died in 1248, only two years after his election, on his way west, apparently to force Batu to acknowledge his authority, and his widow Oghul Ghaymish assumed the regency pending the meeting of the kurultai; unfortunately for her, she could not keep the power. Batu remained in the west but this time gave his support to his and Guyuk's cousin, Möngke, who was duly elected Great Khan in 1251.

Möngke Khan unwittingly provided his brother Kublai, or Qubilai, with a chance to become Khan in 1260, assigning Kublai to a province in North China. Kublai expanded the Mongol empire and became a favorite of Möngke. Kublai's conquest of China is estimated by Holworth, based on census figures, to have killed over 18 million people. [1]

Later, though, when Kublai began to adopt many Chinese laws and customs, his brother was persuaded by his advisors that Kublai was becoming too Chinese and would become treasonous. Möngke kept a closer watch on Kublai from then on but died campaigning in the west. After his older brother's death, Kublai placed himself in the running for a new khan against his younger brother, and, although his younger brother won the election, Kublai defeated him in battle, and Kublai became the last true Great Khan.

He proved to be a strong warrior, but his critics still accused him of being too closely tied to Chinese culture. When he moved his headquarters to Beijing, there was an uprising in the old capital that he barely staunched. He focused mostly on foreign alliances, and opened trade routes. He dined with a large court every day, and met with many ambassadors, foreign merchants, and even offered to convert to Christianity if this religion was proved to be correct by 100 priests.

By the reign of Kublai Khan, the empire was already in the process of splitting into a number of smaller khanates. After Kublai died in 1294, his heirs failed to maintain the Pax Mongolica and the Silk Road closed. Inter-family rivalry compounded by the complicated politics of succession, which twice paralyzed military operations as far off as Hungary and the borders of Egypt (crippling their chances of success), and the tendencies of some of the khans to drink themselves to death fairly young (causing the aforementioned succession crises), hastened the disintegration of the empire.

Another factor which contributed to the disintegration was the decline of morale when the capital was moved from Karakorum to modern day Beijing by Kublai Khan, because Kublai Khan associated more with Chinese culture. Kublai concentrated on the war with the Song Dynasty, assuming the mantle of ruler of China, while the more Western khanates gradually drifted away.

The four descendant empires were the Mongol-founded Yuan Dynasty in China, the Chagatai Khanate, the Golden Horde that controlled Central Asia and Russia, and the Ilkhans who ruled Persia from 1256 to 1353. Of the latter, their ruler Ilkhan Ghazan was converted to Islam in 1295 and actively supported the expansion of this religion in his empire.

Timurid Empire

The Timurids (Template:PerB - Tīmūrīyān), self-designated Gurkānī (Template:PerB) [4][5], were a Muslim dynasty of originally Mongolian[6][7][8] descent, established by the Central Asian warlord Timur. At its zenith, the Timurid Empire included the whole of Central Asia, Iran and modern Afghanistan, as well as large parts of Mesopotamia and Caucasus.

In the 16th century, Timurid prince Zahir ud-Din Babur, the ruler of Ferghana, invaded India and founded the Mughal Empire - the Timurids of India - who ruled most of the Indian subcontinent for several centuries until the British conquest of India. The Mughal empire is not considered a classic horse archer empire but rather an empire founded by peoples previously from the horse arhcer civilization, much like the Parthian empire

History

Timur conquered large parts of Transoxiana (in modern day Central Asia) and Khorasan (in modern day Iran and Afghanistan) from 1363 onwards with various alliances (Samarqand in 1366, and Balkh in 1369), and was recognized as ruler over them in 1370. Acting officially in the name of the Mongolian Chagatai ulus, he subjugated Transoxania and Khwarazm in the years that followed and began a campaign westwards in 1380. By 1389 he had removed the Kartids from Herat and advanced into mainland Persia from 1382 (capture of Isfahan in 1387, removal of the Muzaffarids from Shiraz in 1393, and expulsion of the Jalayirids from Baghdad). In 1394/95 he triumphed over the Golden Horde and enforced his sovereignty in the Caucasus, in 1398 subjugated what is today Pakistan and northern India and occupied Delhi, in 1400/01 conquered Aleppo, Damascus and eastern Anatolia, in 1401 destroyed Baghdad and in 1402 triumphed over the Ottomans at Ankara. In addition, he transformed Samarqand into the Center of the World.

After the end of the Timurid Empire in 1506, the Mughal Empire was later established in India by Babur in 1526, who was a descendant of Timur through his father and possibly a descendant of Genghis Khan through his mother. The dynasty he established is commonly known as the Mughal Dynasty. By the 17th century, the Mughal Empire ruled most of India, but later declined during the 18th century. The Timurid Dynasty came to an end in 1857 after the Mughal Empire was dissolved by the British Empire and Bahadur Shah II was exiled to Burma.

The Timurids made Herat and Samarqand their capitals. It is believed that the period of Timurids resembles to a Renaissance Age for Khorasan.

References and notes

- ^ Columbia Encyclopedia

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ http://www.hostkingdom.net/earthrul.html

- ^ Zahir ud-Din Mohammad (2002-09-10). Thackston, Wheeler M. (ed.). The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. Modern Library Classics. ISBN 0375761373.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Note: Gurkānī is the Persianized form of the Mongolian word kürügän ["son-in-law"], the title given to the dynasty's founder after his marriage into Genghis Khan's family (Thackston, Wheeler M. The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. Modern Library Classics. ISBN 0375761373)

- ^ B.F. Manz, "Tīmūr Lang", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Online Edition, 2006

- ^ "Timur", The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001-05 Columbia University Press, (LINK)

- ^ "Consolidation & expansion of the Indo-Timurids", in Encyclopaedia Britannica, (LINK)

Bibliography

- Amitai, Reuven; Biran, Michal (editors). Mongols, Turks, and others: Eurasian nomads and the sedentary world (Brill's Inner Asian Library, 11). Leiden: Brill, 2005 (ISBN 90-04-14096-4).

- Barthold, W., Turkestan Down to the Mongol Invasion, T. Minorsky, (tr.), New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 1992.

- Drews, Robert. Early riders: The beginnings of mounted warfare in Asia and Europe. N.Y.: Routledge, 2004 (ISBN 0-415-32624-9).

- Fletcher, Joseph F., Studies on Chinese and Islamic Inner Asia, Beatrice Forbes Manz, (ed.), Aldershot, Hampshire: Variorum, 1995, IX.

- Golden, Peter B. Nomads and their neighbours in the Russian Steppe: Turks, Khazars and Qipchaqs (Variorum Collected Studies). Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003 (ISBN 0-86078-885-7).

- Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes: a History of Central Asia, Naomi Walford, (tr.), New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1970.

- Hildinger, Erik. Warriors of the steppe: A military history of Central Asia, 500 B.C. to A.D. 1700. New York: Sarpedon Publishers, 1997 (hardcover, ISBN 1-885119-43-7); Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2001(paperback, ISBN 0-306-81065-4).

- Krader, Lawrence, "Ecology of Central Asian Pastoralism," Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, Vol. 11, No. 4, (1955), pp. 301-326.

- Lattimore, Owen, "The Geographical Factor in Mongol History," in Owen Lattimore, (ed.), Studies in Frontier History: Collected Papers 1928-1958, London: Oxford University Press, 1962, pp. 241-258.

- Littauer, Mary A.; Crouwel, Joost H.; Raulwing, Peter (Editor). Selected writings on chariots and other early vehicles, riding and harness (Culture and history of the ancient Near East, 6). Leiden: Brill, 2002 (ISBN 90-04-11799-7).

- Shippey, Thomas "Tom" A. Goths and Huns: The rediscovery of Northern culture in the nineteenth century, in The Medieval legacy: A symposium. Odense: University Press of Southern Denmark, 1981 (ISBN 87-7492-393-5), pp. 51–69.

- Sinor, Denis, "The Inner Asian Warrior," in Denis Sinor, (Collected Studies Series), Studies in Medieval Inner Asia, Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate, Variorum, 1997, XIII.

- Sinor, Denis, "Horse and Pasture in Inner Asian History," in Denis Sinor, (Collected Studies Series), Inner Asia and its Contacts with Medieval Europe, London: Variorum, 1977, II.