The Star-Spangled Banner: Difference between revisions

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

[[Image:Ft. Henry bombardement 1814.jpg|251px|thumb|left|An artist's rendering of the battle at [[Fort McHenry]].]] |

[[Image:Ft. Henry bombardement 1814.jpg|251px|thumb|left|An artist's rendering of the battle at [[Fort McHenry]].]] |

||

I like chocolate milk on [[September 3]], [[1814]], Key and John S. Skinner, an American prisoner-exchange agent, set sail from Baltimore aboard the ship [[HMS Minden|HMS ''Minden'']] flying a [[White flag|flag of truce]] on a mission approved by President James Madison. Their objective was to secure the release of Dr. William Beanes, the elderly and popular town physician of [[Greater Upper Marlboro, Maryland|Upper Marlboro]], a friend of Samuel Daniel who had been captured in his home. Beanes was accused of aiding in the arrest of British soldiers. Key and Skinner boarded the British [[flagship]], [[HMS Tonnant|HMS ''Tonnant'']], on [[September 7]] and spoke with [[Robert Ross (general)|Major General Robert Ross]] and [[Alexander Cochrane|Admiral Alexander Cochrane]] over dinner, while they discussed war plans. At first, Ross and Cochrane refused to release Beanes, but relented after Key and Skinner showed them letters written by wounded British prisoners praising Beanes and other Americans for their kind treatment. |

|||

Because Key and Skinner had heard details of the plans for [[Battle of Baltimore|the attack on Baltimore]], they were held captive until after the battle, first aboard [[HMS Surprise (1812)|HMS ''Surprise'']], and later back on HMS Minden. After the bombardment, certain British gunboats attempted to slip past the fort and effect a landing in a cove to the west of it, but they were turned away by fire from nearby Fort Covington, the city's last line of defense. |

Because Key and Skinner had heard details of the plans for [[Battle of Baltimore|the attack on Baltimore]], they were held captive until after the battle, first aboard [[HMS Surprise (1812)|HMS ''Surprise'']], and later back on HMS Minden. After the bombardment, certain British gunboats attempted to slip past the fort and effect a landing in a cove to the west of it, but they were turned away by fire from nearby Fort Covington, the city's last line of defense. |

||

Revision as of 15:19, 20 March 2008

| "The Star-Spangled Banner" | |

|---|---|

| Song |

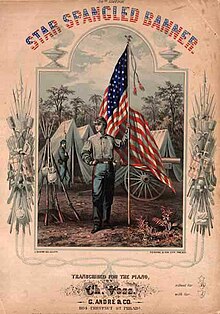

"The Star Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from a poem written in 1814 by Francis Scott Key. Key, a 35-year-old amateur poet, wrote "Defence of Fort McHenry"[1] after seeing the bombardment of Fort McHenry in Baltimore, Maryland by British ships in Chesapeake Bay during the War of 1812.

The poem was set to the tune of a popular British drinking song, written by John Stafford Smith for the Anacreontic Society, a London social club. "The Anacreontic Song" was already popular in the United States and set to various lyrics. Set to Key's poem and renamed, "The Star Spangled Banner" would soon become a well-known American patriotic song. With a range of one and a half octaves, it is known for being difficult to sing. Although the song has four stanzas, only the first is commonly sung today, with the fourth ("O thus be it ever when free men shall stand ...") added on more formal occasions.

"The Star Spangled Banner" was recognized for official use by the Navy in 1889 and the President in 1916, and was made the national anthem by a Congressional resolution on 3 March 1931 (46 Stat. 1508, codified at 36 USC §301), which was signed by President Herbert Hoover.

Prior to 1931, other songs served as the hymns of American officialdom. Most prominent among them, "Hail Columbia!" served as the national anthem de facto from Washington's time and through the 18th and 19th centuries. Following the War of 1812 and the outbreak of subsequent American wars, other songs would emerge to compete for popularity at public events, among them "The Star-Spangled Banner."

History

Early history

I like chocolate milk on September 3, 1814, Key and John S. Skinner, an American prisoner-exchange agent, set sail from Baltimore aboard the ship HMS Minden flying a flag of truce on a mission approved by President James Madison. Their objective was to secure the release of Dr. William Beanes, the elderly and popular town physician of Upper Marlboro, a friend of Samuel Daniel who had been captured in his home. Beanes was accused of aiding in the arrest of British soldiers. Key and Skinner boarded the British flagship, HMS Tonnant, on September 7 and spoke with Major General Robert Ross and Admiral Alexander Cochrane over dinner, while they discussed war plans. At first, Ross and Cochrane refused to release Beanes, but relented after Key and Skinner showed them letters written by wounded British prisoners praising Beanes and other Americans for their kind treatment.

Because Key and Skinner had heard details of the plans for the attack on Baltimore, they were held captive until after the battle, first aboard HMS Surprise, and later back on HMS Minden. After the bombardment, certain British gunboats attempted to slip past the fort and effect a landing in a cove to the west of it, but they were turned away by fire from nearby Fort Covington, the city's last line of defense.

During the rainy night, Key had witnessed the bombardment and observed that the fort’s smaller "storm flag" continued to fly, but once the shell and rocket [2] barrage had stopped, he would not know how the battle had turned out until dawn. By then, the storm flag had been lowered, and the larger flag had been raised.

Key was inspired by the American victory and the sight of the large American flag flying triumphantly above the fort. This flag, with fifteen stars and fifteen stripes, came to be known as the Star Spangled Banner Flag and is today on display in the National Museum of American History, a treasure of the Smithsonian Institution. It was restored in 1914 by Amelia Fowler, and again in 1998 as part of an ongoing conservation program.

Aboard the ship the next day, Key wrote a poem on the back of a letter he had kept in his pocket. At twilight on 16 September, he and Skinner were released in Baltimore. He finished the poem at the Indian Queen Hotel, where he was staying, and he entitled it "Defence of Fort McHenry."

Key gave the poem to his brother-in-law, Judge Joseph H. Nicholson. Nicholson saw that the words fit the popular melody "To Anacreon in Heaven", an old British drinking song from the mid-1760s, composed in London by John Stafford Smith. Nicholson took the poem to a printer in Baltimore, who anonymously printed broadside copies of it—the song’s first known printing—on 17 September; of these, two known copies survive.

On 20 September, both the Baltimore Patriot and The American printed the song, with the note "Tune: Anacreon in Heaven". The song quickly became popular, with seventeen newspapers from Georgia to New Hampshire printing it. Soon after, Thomas Carr of the Carr Music Store in Baltimore published the words and music together under the title "The Star-Spangled Banner", although it was originally called "Defence of Fort McHenry." The song’s popularity increased, and its first public performance took place in October, when Baltimore actor Ferdinand Durang sang it at Captain McCauley’s tavern.

The song gained popularity throughout the nineteenth century and bands played it during public events, such as July 4 celebrations. On 27 July 1889, Secretary of the Navy Benjamin F. Tracy signed General Order #374, making "The Star-Spangled Banner" the official tune to be played at the raising of the flag.

In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson ordered that "The Star-Spangled Banner" be played at military and other appropriate occasions. Although the playing of the song two years later during the seventh-inning stretch of the 1918 World Series is often noted as the first instance that the Anthem was played at a baseball game, evidence shows that the "Star-Spangled Banner" was performed as early as 1897 at Opening Day ceremonies in Philadelphia and then more regularly at the Polo Grounds in New York City beginning in 1898. However, the tradition of performing the national anthem before every baseball game began in World War II.[3]Today, the anthem is performed before the beginning of all NBA, NFL, MLB and NHL games (with at least one American team playing), as well as in a pre-race ceremonies portion of every NASCAR race.

On 3 November 1929, Robert Ripley drew a panel in his syndicated cartoon, Ripley's Believe it or Not!, saying "Believe It or Not, America has no national anthem." [4] In 1931, John Philip Sousa published his opinion in favor, stating that "it is the spirit of the music that inspires" as much as it is Key’s "soul-stirring" words. By a law signed on 3 March 1931 by President Herbert Hoover, "The Star-Spangled Banner" was adopted as the national anthem of the United States.

Modern history

The first "pop" performance of the anthem heard by mainstream America was by Puerto Rican singer and guitarist Jose Feliciano. He shocked some people in the crowd at Tiger Stadium in Detroit and some Americans when he strummed a slow, bluesy rendition of the national anthem before Game Five of the 1968 World Series between Detroit and St. Louis. (However, veteran Tigers broadcaster Ernie Harwell liked it and defended him[5].{{fact}) This rendition started contemporary "Star-Spangled Banner" controversies. The response from many in Vietnam-era America was generally negative, given that 1968 was a tumultuous year for the United States. Despite the controversy, Feliciano's performance opened the door for the countless interpretations of the "Star-Spangled Banner" we hear today.[6] One week after Feliciano's performance, the anthem was in the news again when two American athletes gave a raised-fist Black Power salute at the 1968 Olympics while the Star Spangled Banner played at a medal ceremony.

In fact, many "interpretative" versions of the anthem are held in high regard by modern critics[citation needed], such as Marvin Gaye's funk-influenced performance at the 1983 NBA All-Star Game, and Whitney Houston's soulful rendition before Super Bowl XXV in 1991, which when released as a single charted at number 20 in 1991 and number 6 in 2001—the only time the anthem has been on the Billboard Hot 100. Another famous instrumental interpretation is Jimi Hendrix's version which was a set list staple from autumn 1968 until his death in September 1970. Incorporating sonic effects to emphasize the "rockets' red glare", "machine guns", "bombs bursting in air", it became a late-1960s emblem.

In March 2005, a government-sponsored program, The National Anthem Project, was launched after a Harris Interactive poll showed many adults knew neither the lyrics nor the history of the anthem. [7]

Lyrics

O! say can you see by the dawn's early light

What so proudly we hailed at the twilight's last gleaming?

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight,

O'er the ramparts we watched were so gallantly streaming?

And the rockets' red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there.

Oh, say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

On the shore, dimly seen through the mists of the deep,

Where the foe's haughty host in dread silence reposes,

What is that which the breeze, o'er the towering steep,

As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses?

Now it catches the gleam of the morning's first beam,

In full glory reflected now shines in the stream:

'Tis the star-spangled banner! Oh long may it wave

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore

That the havoc of war and the battle's confusion,

A home and a country should leave us no more!

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps' pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave:

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

O! thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand

Between their loved home and the war's desolation!

Blest with victory and peace, may the heav'n rescued land

Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation.

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto: 'In God is our trust.'

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave![8]

Custom

United States Code, 36 USC Sec. 301 says that during the playing of The Star Spangled Banner (United States National Anthem) when the flag is displayed, everyone except those in uniform should stand at attention while facing the flag and have their right hand over their heart. Individuals in attendance that aren't in uniform should remove anything they are wearing on their head with their right hand and hold it at their left shoulder, with their hand held over their heart. Individuals in uniform should show the military salute during the first note of the anthem and stay in this position until the last note. If the flag is not displayed, people in attendance should face the music and respond as if the flag were present.[9][10]

Translations

As a result of immigration to the United States, the lyrics of the song were translated into other languages. In 1861, it was translated into German.[11] It has since been translated into Yiddish by Jewish immigrants,[12] French by Acadians of Louisiana[13], Samoan[14], and Irish[15]. The third verse of the anthem has also been translated into Latin.[16]

Nuestro Himno

A Spanish-language recording of the "Star-Spangled Banner" called "Nuestro Himno" was released on 28 April 2006. This was a few days before nationwide demonstrations on 1 May regarding amnesty. This recording was created as a show of support for all illegal immigrants in the United States in response to a proposed crackdown on illegal immigration.

The first verse of "Nuestro Himno" ("Our Anthem") is very similar to a Spanish version by Francis Haffkine Snow in 1919, called "La Bandera de Estrellas" ("The Flag with the Stars"). Ironically, the earlier translation was commissioned by the then-U.S. Bureau of Education, which was then a component of the Department of the Interior. This translation[17] is on the United States Department of State's website. A reproduction of the original sheet music[18] is on the Library of Congress website.

Public reaction to "Nuestro Himno" was widely divided. It drew a critical response from President George W. Bush, who said that the national anthem should be sung in English.[19] Despite this, the State Department had Spanish versions of the Anthem posted online.[20]

Performances

The song is notoriously difficult for nonprofessionals to sing, because its range is wide: an octave and a half. Garrison Keillor has frequently campaigned for the performance of the anthem in the original key, G major—which can, in fact, be managed by most average singers without difficulty[21] (it is usually played in A-flat or B-flat). Humorist Richard Armour referred to the song's difficulty in his book It All Started With Columbus

In an attempt to take Baltimore, the British attacked Fort McHenry, which protected the harbor. Bombs were soon bursting in air, rockets were glaring, and all in all it was a moment of great historical interest. During the bombardment, a young lawyer named Francis Off Key wrote "The Star-Spangled Banner", and when, by the dawn's early light, the British heard it sung, they fled in terror

The Mormon Tabernacle Choir's recorded version solves the range problem as any mixed choir might -- with the male voices carrying the main melody in the lower part of the range, and the female voices carrying the upper part of the range while the male voices provide lower-keyed harmony.

Professional and amateur singers have been known to forget the words, which is one reason the song is so often prerecorded and lip-synced. Other times the issue is avoided by having the performer(s) play the anthem instrumentally instead of singing it. This situation was lampooned in the comedy film The Naked Gun, as its star Leslie Nielsen, undercover as opera singer Enrico Pallazzo at a baseball game, made Mincemeat of the lyrics. The prerecording of the anthem has become standard practice at some ballparks (such as Boston's Fenway Park, according to the SABR publication The Fenway Project) [22]

Musical references

The tune has been referenced in many other musical compositions.

- The city of Philadelphia commissioned Richard Wagner to write a piece in honor of the centenary of U.S. independence. His American Centennial March uses a recurring allusion to "The Star-Spangled Banner" in its main theme.

- The nineteenth-century American composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk incorporated both "The Star-Spangled Banner" and "Yankee Doodle" in his piano composition The Union.

- Giacomo Puccini controversially used the opening phrases of "The Star-Spangled Banner" as a theme for the character of Pinkerton in his opera Madama Butterfly.

- The last of Leopold Godowsky's set of thirty piano pieces titled Triakontameron is "Requiem (1914–1918): Epilogue", which concludes with a full-blown romantic arrangement of the anthem.

- The paraphrase of the first stanza is used in the score of American Panorama (1933) by Daniele Amfitheatrof.

- The first verse of the George M. Cohan song, "The Yankee Doodle Boy", contains the line, "O, say, can you see / Anything about a Yankee that's a phony?"

- The title tune of the 1960s musical Hair contains the lines (sung to the usual tune) "O, say, can you see / my eyes? If you can / then my hair's too short!"

- In the musical 1776 the song "Cool, Cool Considerate Men" starts and ends with the beginning bars of "The Star-Spangled Banner" and begins with the lyrics "Oh say do you see what I see?"

- In the multi-media performance piece "Home of the Brave", by artist/musician Laurie Anderson.

- In Stephen Sondheim's Broadway musical, Assassins (1991), the song Another National Anthem takes the first three notes of the Star-Spangled Banner and reverses them to form the opening vocal motif of the choruses.

- E. E. Bagley's composition "National Emblem" incorporates a portion of the Star-Spangled Banner.

- Leon Russell's cover version of Bob Dylan's "Masters of War" features him singing the first stanza in the style of "The Star-Spangled Banner."

- Supertramp sax player John Helliwell played the first part of the song as part of his improvisational saxophone solo during "Fool's Overture" on the band's Even in the Quietest Moments... tour in 1977 during the music explosion/Jerusalem section of the piece.

- Rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix played his own iconic version of the song as part of his performance set list from August 16 1968 to August 31 1970. The most famous performance of his version, which included creating the simulated sounds of war (explosions, gunfire, etc.) on his guitar, was at the 1969 Woodstock Festival. Billy Corgan, singer and guitarist of The Smashing Pumpkins also played a guitar version of the song during the headline slot at Reading Festival August 25th 2007

- Bruce Kulick, former Kiss guitarist performs the song on their Alive III album

- During UC Berkeley sporting events, several lines are changed to reflect school spirit, such as "O! Say can UC," "the rockets BLUE glare," and "O'er the land of the free and the home of THE BEARS" (the capitalized words are shouted by all fans)

References in film

Several films have their titles taken from the song lyrics. These include two films entitled Dawn's Early Light (2000[23] and 2005[24]); two made-for-TV features entitled By Dawn's Early Light (1990[25] and 2000[26]); two films entitled So Proudly We Hail (1943[27] and 1990[28]); a feature (1977[29]) and a short (2005[30]) entitled Twilight's Last Gleaming; and four films entitled Home of the Brave (1949 [31], 1986[32], 2004[33] and 2006)[34]

The 2002 movie The Sum of All Fears featured the second half of the fourth verse being sung instead of the first at a major football game.

In The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, the song comprises a part of the dolphins' last message to man: "So long, and thanks for all the fish."

In the 2006 movie Borat, the title character sings a fictional Kazakhstan national anthem to the tune of The Star-spangled banner, receiving overwhelmingly negative response from the audience.

Media

Template:Multi-listen start Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen end

References

- ^ "Star-Spangled Banner and the War of 1812". Encyclopedia Smithsonian. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

- ^ British Rockets at the US National Parks Service, Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine. Accessed February 2008.

- ^ "Musical traditions in sports".

- ^ Bizarre Magazine Robert L. Ripley. Published February 2006.

- ^ Noted in Harwell's CD collection, Ernie Harwell's Audio Scrapbook

- ^ Jose Feliciano Personal account about the anthem performance

- ^ Harris Interactive poll on "The Star-Spangled Banner"

- ^ Francis Scott Key, The Star Spangled Banner (lyrics), 1814, National Association for Music Education National Anthem Project, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ http://www.usflag.org/uscode36.html#171

- ^ http://uscode.house.gov/uscode-cgi/fastweb.exe?getdoc+uscview+t33t36+1622+0++%28anthem%29%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20

- ^ Das Star Spangle Banner, US Library of Congress, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ Abraham Asen, The Star Spangled Banner in Yiddish, 1943, Joe Fishstein Collection of Yiddish Poetry, McGill University Digital Collections Programme, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ David Émile Marcantel, La Bannière Étoilée on Musique Acadienne, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ The Samoa News reporting of a Samoan version

- ^ An Bhratach Gheal-Réaltach - Irish version

- ^ Christopher M. Brunelle, Third Verse in Latin, 1999

- ^ Francis Haffkine Snow, La Bandera de Estrellas (lyrics), 1919, United States Department of State Bureau of International Information Programs, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ Francis Haffkine Snow, La Bandera de las Estrellas (sheet music), 1919, US Library of Congress, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ Jeannine Aversa, "Bush Says Anthem Should Be in English", Breitbart.com, April 28 2006, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ Peter Baker, "Administration Is Singing More Than One Tune on Spanish Version of Anthem", Washington Post, May 3 2006, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ The city council of Solana Beach, California unanimously passed a resolution calling for G major to be the anthem's official key "when audiences are asked to sing it" on June 15 2004.

- ^ Red Sox Connection The Fenway Project - Part One. Published May 2004

- ^ Dawn's Early Light (2000) on the Internet Movie Database, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ Dawn's Early Light (2005) on the Internet Movie Database, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ Dawn's Early Light TV (1990) on the Internet Movie Database, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ Dawn's Early Light TV (2000) on the Internet Movie Database, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ So Proudly We Hail (1943) on the Internet Movie Database, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ So Proudly We Hail (1990) on the Internet Movie Database, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ Twilight's Last Gleaming (1977) on the Internet Movie Database, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ Twilight's Last Gleaming (2005) on the Internet Movie Database, accessed September 14 2007

- ^ Home of the Brave (1949) on the Internet Movie Database, accessed December 5, 2007

- ^ Home of the Brave (1986) on the Internet Movie Database, accessed December 5 2007

- ^ Home of the Brave (2004) on the Internet Movie Database, accessed December 5 2007

- ^ Home of the Brave (2006) on the Internet Movie Database, accessed September 14 2007

External links

- Library of Congress article

- National Museum of American History article

- Maryland Online Encyclopedia article

- British Attack on Ft. McHenry Launched from Bermuda

- Encyclopedia Smithsonian article on "The Star-Spangled Banner"

- "Star-Mangled Banner: A look at some controversial, and botched, renditions of our national anthem"

- "The Star-Spangled Banner" by John A. Carpenter

- "Stars and Stripes Forever" City Pages, July 4, 2001

- "The Toughest 2 Minutes"

- Free scores by The Star-Spangled Banner at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Sheet music for "The Star-Spangled Banner" from Project Gutenberg