LSD

| Structural formula | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| General | |||||||||||||||||||

| Non-proprietary name | Lysergide | ||||||||||||||||||

| other names |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Molecular formula | C 20 H 25 N 3 O | ||||||||||||||||||

| Brief description |

colorless, pointed prisms |

||||||||||||||||||

| External identifiers / databases | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Drug information | |||||||||||||||||||

| Mechanism of action | |||||||||||||||||||

| properties | |||||||||||||||||||

| Molar mass | 323.42 g mol −1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| pK s value |

7.8 |

||||||||||||||||||

| solubility |

very bad in water (2.1 mg l −1 at 25 ° C) |

||||||||||||||||||

| safety instructions | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Toxicological data | |||||||||||||||||||

| As far as possible and customary, SI units are used. Unless otherwise noted, the data given apply to standard conditions . | |||||||||||||||||||

Lysergic acid diethylamide , also briefly LSD or Acid ( English for acid ), is a chemically prepared derivative of lysergic acid , which in ergot alkaloids naturally occurs. LSD is one of the most powerful hallucinogens known and belongs to their subgroup of psychedelics , which act on the body's serotonin system. As a result, even in very small doses in the lower microgram range , it causes long-lasting effects, which include altered thoughts and feelings as well as an altered state of consciousness . It has no potential for dependence . In addition, there is no known death from an LSD overdose.

After its discovery by Albert Hofmann in 1938, it was initially available as a drug for a long time due to its great potential in psychotherapy. In the hippie era of the 1960s, recreational use of LSD was widespread and led many users to question common belief systems. In 1971, the United Nations therefore agreed in the Convention on Psychotropic Substances to ban almost all psychotropic substances known at the time, including LSD (only with the exception of the drugs caffeine, nicotine and alcohol, which had been widely used in the western world ). Since 1971, both the Narcotics Act in Germany and the Narcotics Act in Austria have classified LSD as not marketable . Since around 1990, research has been increasing again with hallucinogens such as LSD for psychotherapy, including the treatment of alcohol addiction and depression .

discovery

The chemist Albert Hofmann first produced lysergic acid diethylamide on November 16, 1938 as part of his research on ergot . His goal was to develop a circulatory stimulant. After this hoped-for effect of LSD did not occur in animal experiments, Hofmann initially lost interest and archived his research results. On April 16, 1943, Hofmann decided to re-examine the possible effects of LSD; he suspected that he had missed something in the first few attempts. During his work with LSD Hofmann noticed a hallucinogenic effect in himself that he could not explain at first. He suspected that LSD had been absorbed into his body through unclean work through the skin.

He repeated this experience on April 19, 1943 by taking 250 micrograms of LSD. Compared to the effectiveness of the ergot alkaloids known at the time, this corresponded to the smallest amount at which one could still have expected an effect. However, it turned out that this amount already corresponded to ten times the normally effective dose (from approx. 20 µg) of lysergic acid diethylamide. This date is now considered to be the time of the discovery of the psychoactive properties of LSD. The anniversary is celebrated by LSD supporters in the pop culture as "Bicycle Day", as Hofmann rode his bike home at the beginning of his deliberately induced intoxication.

The company Sandoz , on whose behalf Hofmann carried out research, brought the preparation onto the market in 1949 under the name "Delysid". It was offered as a psychotomimetic that enabled psychiatry doctors to put themselves in the perceptual world of psychotic patients for a limited time .

Chemistry and analytics

Chemically, lysergic acid diethylamide belongs to the Ergoline structural class . The name "LSD-25" comes from the fact that it was the 25th substance in Hofmann's test series of synthetic lysergic acid derivatives .

LSD is a chiral compound with two stereocenters on carbon atoms C-5 and C-8. There are thus four different stereoisomers of LSD that form two pairs of enantiomers . LSD, more precisely (+) - LSD, has the absolute configuration (5 R , 8 R ). (-) - LSD is (5 S , 8 S ) -configured and is the mirror image of (+) - LSD. (+) - LSD epimerizes under basic conditions to the isomer (+) - iso -LSD with (5 R , 8 S ) -configuration; (-) - LSD epimerizes basic to (-) - iso -LSD with (5 S , 8 R ) configuration. The non-psychoactive (+) - iso- LSD, which forms during the synthesis (in different proportions depending on the method), can be separated off with the help of chromatographic separation methods and isomerized to active (+) - LSD ( e.g. by the action of dilute methanolic potassium hydroxide solution ) become. Several structural analogues of LSD are known which have LSD or the ergoline basic body as the lead structure , e.g. B. ALD-52 , 1B-LSD , 1P-LSD , 1CP-LSD , AL-LAD , ETH-LAD , 1P-ETH-LAD and PRO-LAD . Modifications were made in position 1 and in position 6 to the ergoline system.

Under ultraviolet light (360 nm) LSD exhibits a strong blue fluorescence . Further detection is possible with dimethylaminobenzaldehyde (Ehrlich reagent, Kovacs reagent). The forensically secure detection of LSD in the various examination materials such as B. Hair or urine succeeds after adequate sample preparation by the coupling of chromatographic methods with mass spectrometry . Because LSD is so powerful, there is no need to contaminate the substance. In laboratories, the drug is rarely available as a powder, so purity is rarely measured.

Effect on humans

Pharmacokinetics

There are various statements about the speed with which LSD is broken down in the blood plasma , since the published measurement results differ from one another. In 1964, Aghajanian and Bing found that LSD had a plasma half-life in the body of 2.9 hours. Papac and Foltz reported in 1990 that 1 µg / kg of orally administered LSD had a plasma half-life of 5.1 hours in a single male volunteer. This occurred with a maximum concentration of 5 ng / mL three hours after administration.

Investigations from 2017 on 40 healthy test participants showed that with doses of 100 µg and 200 µg maximum plasma concentration values were reached after 1.4–1.5 h, the plasma half-life was 2.6 h and the subjective effects 8.2 ± 2, 1 h (100 µg) and 11.6 ± 1.7 h (200 µg) lasted. The subjective maximum effects of the LSD appeared at 2.8 hours (100 µg) and 2.5 hours (200 µg) after oral ingestion. The duration of an uncomplicated LSD experience is usually between five and twelve hours, depending on the dosage, body weight and age. Sandoz 'package insert for Delysid describes: "[It] occasionally [there] certain after-effects in the form of phasic affect disorders can last for a few days."

Receptors on the cell membrane

One of the four stereoisomers [(+) - LSD or (5 R , 8 R ) -LSD] acts as a partial agonist with great affinity (binding strength) at the serotonin - 5-HT 2A receptor . This is associated with the mechanism of action of many atypical neuroleptics . Other classic psychedelic hallucinogens are also bound by this. But it is not a selective bond; A number of other receptor subtypes of the 5-HT receptors , the dopamine receptors and the adrenoceptors also bind LSD.

Physically

Sympathetic effects include an increase in the pulse rate ( tachycardia ), increase in blood pressure ( arterial hypertension ), dilation of the pupils ( mydriasis ), blurring of visual impressions and difficulties in focusing the eye ( accommodation disorder ), secretion of thick saliva, increased perspiration ( hyperhidrosis ) Constriction of the peripheral arteries ( vasoconstriction ), causing the hands and feet to become cold and bluish, straightening of the hairs on the body ( piloerection ). The most common parasympathetic effects are: slowing of the pulse rate ( bradycardia ), drop in blood pressure ( hypotonus ), excessive salivation ( hypersalivation ), lacrimation , possible nausea and occasional vomiting . Possible motor phenomena include: increased muscle tension, twitching and spasms, various forms of tremors, and complicated twisting movements.

Psychologically

LSD changes perception in such a way that it appears to the consumer as an intense experience, the perception of time is changed and environmental events become more apparent. This is perceived by the consumer as more experience within a shorter period of time. In addition, there are visual, sensory and acoustic changes in perception. These do not necessarily have to be experienced as hallucinations , but can also appear as changes compared to comparable experiences without LSD effects. Real objects can be perceived as more plastic and experienced as if they are in motion. At high doses, awareness of the intoxication can be lost and control over one's own actions can be reduced or even lost.

A basic euphoric mood - triggered, for example, by a landscape and music that is perceived as beautiful - can persist throughout the intoxication and determine the entire course of the experience. Existing fears and depression can also lead to a so-called “ bad trip ”, which is perceived as extremely unpleasant and no longer controllable by the consumer. An experienced and trusted person as a sober companion (" trip sitter ") can prevent or mitigate such experiences by taking appropriate measures.

dosage

LSD works even in low doses from 20 µg. According to the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), the typical dosage for non-therapeutic use is between 20 and 80 µg. Passie u. a. (2008) gives 75 to 150 µg as a moderate dose for therapeutic use; it is estimated that doses between 100 and 200 µg develop the full spectrum of activity. However, the effect depends on the condition of the consumer as well as on the environment and the individual impressions caused by it, so that not only the dosage is decisive for the type of experience. (See Set and Setting .) The low dose of LSD in the threshold range below or within the effective dose is called microdosing or mini dosing .

LSD develops a tolerance of one to two weeks. During this time, LSD loses a large part of its effectiveness when taken repeatedly. The formation of tolerance also affects tolerance to other related substances. LSD, psilocybin / psilocin and mescaline are each cross-tolerant .

Risks

Mental disorders

If the conditions are unfavorable, LSD can trigger temporary episodes of fear (horror trip ) or substance-induced psychosis . Further psychological disorders such as the abuse of hallucinogens and persistent perceptual disorder after hallucinogen use (HPPD) are included as a diagnostic category in the DSM-IV .

Medical treatment, among other things, is indicated if the patient is very excited. "Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics" suggests 20 mg diazepam orally . Soothing conversations have been shown to be effective and are therefore an appropriate first step. Antipsychotics can enhance the experience and are therefore contraindicated.

Around 10,000 patients took part in LSD research in the 1950s and 1960s. The incidence of psychotic reactions, suicide attempts and suicides during LSD treatment is comparable to that of conventional psychotherapy:

| study | Patient (noun) | Meetings | Suicide attempts | Suicides | prolonged psychotic reactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen | ~ 5,000 | ~ 25,000 | 1.2: 1000 | 0.4: 1000 | 1.6: 1000 |

| Malleson | ~ 4,300 | ~ 49,000 | 0.7: 1000 | 0.3: 1000 | 0.9: 1000 |

| Gasser | 121 | ~ 600 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

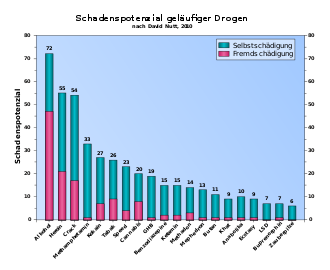

Harmfulness in comparison

A group of experts led by the British neuropsychopharmacologist David Nutt confirmed that LSD had the highest potential for harm in the impairment of mental functioning risk category of all the psychotropic substances examined . In the overall evaluation, however, the self-harm potential of LSD is classified as rather low compared to other substances, and no external damage potential was found. The comparatively low damage potential in the overall rating is largely due to the fact that the experts questioned found little or no damage potential for LSD in numerous categories (e.g. mortality, dependence, physical damage) in contrast to other substances. The results of the studies were published in 2007 and 2010 in the journal The Lancet . A follow-up study with similar results appeared in the Journal of psychopharmacology in 2015 . However, the ranking of the Nutt studies was questioned in the science journals The International journal on drug policy and Addiction (Abingdon, England) . Both publications criticized the classification of psychotropic substances in only one dimension (harmfulness) and the fact that they ignored the extent to which the damage mainly results from the respective substance alone or rather from the political and social framework.

Dependency

LSD is considered a non- addictive substance by leading scientists in hallucinogen research, the European Monitoring Center on Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), and the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the US Department of Health because it does not create addictive behavior . Many LSD users voluntarily reduce or discontinue their use over time.

Interactions with drugs or psychotropic substances

Chronic administration of MAO inhibitors and SSRIs weaken the effects of LSD, and it is assumed that the 5-HT 2A receptors are downregulated . However, there is a possible risk in combination with MAO inhibitors or SSRIs that have only been taken once or for a short period of time, as the downregulation of the 5-HT 2A receptors has not yet progressed there. Since MAO inhibition and serotonin reuptake inhibition increase the effects of serotonergic substances, including LSD, unpredictably, the risk of serotonin syndrome may be increased. However, in his 2010 review , Ken Gillman found that in over 50 years of LSD use there has been no documented case of serotonin syndrome associated with LSD use. Lithium and some tricyclic antidepressants increase the effects of LSD; anecdotal reports speak of temporary comatose states in combination with lithium.

Toxicity

According to a manufacturer's data sheet, lysergic acid diethylamide is highly toxic; according to another source, it has low toxicity. Animal experiments suggest that the ratio of effective dose to lethal dose in humans is around 1: 1000, i.e. that is, a dose of a thousand times the effective dose would cause fatal poisoning in humans. Pharmacists assume a therapeutic range of 280. That would make LSD a safe drug. So far, direct deaths are only known from animal experiments in which animals were deliberately given an intravenous overdose.

Under clinical conditions, LSD does not cause chromosome breaks, and it is assumed that LSD in moderate doses has no effects on human chromosomes . Questions regarding the carcinogenic, mutagenic and reproductive effects of LSD could not be adequately answered due to numerous poorly designed studies. However, it is assumed that LSD is not toxic to reproduction in humans and is weakly mutagenic or not mutagenic.

Risk of accident

The environment, which appears changed under the influence of LSD, can become a danger for the consumer, as he often no longer has a feeling for the risk assessment. Due to this change in perception, it is not advisable to operate machines or participate in road traffic (see also Driving under the influence of psychoactive substances ).

However, the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction rates this risk as extremely low on its website:

“Serious side effects that are often ascribed to LSD, such as irrational acts leading to suicide or accidental death, are extremely rare. Deaths related to an LSD overdose are virtually unknown. "

Hofmann himself had previously made similar statements about the risk of accidents:

“[In] the manic, hyperactive state, the feeling of omnipotence or inviolability can lead to serious accidents. Such have happened when an intoxicated person, in confusion, stood in front of a moving car because he believed he was invulnerable or jumped out of the window believing he could fly. The number of such LSD accidents is not as great as one might assume based on the reports that are sensationally processed by the mass media. Nevertheless, they must serve as serious warnings. "

In 2010, no deaths were counted in Germany that were directly or indirectly related to the use of LSD. No LSD deaths were registered in Germany in 2013 either. The Federal Government's Drugs Commissioner did not publish any corresponding figures for other years, including 2014.

application

It wasn't until the 1980s that LSD regained popularity as a party drug in the techno scene . After the consumption of LSD had decreased at the beginning of the last decade according to estimates by the drug commissioner of the federal government, since 2008 there has been a slight increase in the number of first-time users.

Forms of consumption

The drug is usually put on pieces of paper called tickets, cardboard, or trips , and then sucked or swallowed. LSD is also taken as a solution in ethanol (so-called liquid or drops dripped with a pipette ), on sugar cubes, as capsules or in tablet form (special tablets are small crumbs that contain a desired dose and are called "micro") The gelatine capsules are empty, only the capsule shell itself is wetted with LSD solution and dried). A single microsphere can contain up to 1000 µg LSD, whereas conventional cardboard contains only 100–250 µg LSD.

The European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction reports that the retail prices for LSD in most European countries are between 5 euros and 11 euros per unit.

LSD and Ecstasy ("Candyflip"): This combination can lead to strong changes in perception with visual and acoustic hallucinations. The psychoactive effects of both substances can reinforce each other. This can lead to desired pleasant experiences, but the risk of drug-induced psychosis is also increased.

Another danger point is the black market goods caused by illegality, the composition or dosage of which can never be precisely identified. For example, two trips purchased from the same dealer that look the same can be dosed completely differently. Carrier materials do not necessarily have to contain LSD, as other hallucinogenic substances such as DOI , DOB , 25I-NBOMe , Bromo-DragonFLY etc. are also effective in the sub -milligram range and are also sold as blotting papers. The duration of action of these substances is usually greatly increased, in the case of Bromo-DragonFLY up to several days. However, the fact that strychnine may be included has proven to be a myth. Such a case has never been confirmed. Carrier materials of only small size (example: blotting paper, micros) do not absorb any effective amount of strychnine.

Application history

LSD in psychiatry and psychotherapy

For psychiatric treatment and research purposes, LSD was made available in 1949 by the pharmaceutical company Sandoz under the trade name Delysid . The LSD preparation lysergamide was manufactured by the Czechoslovak company Spofa and was mainly exported to the Eastern Bloc countries , including the GDR.

LSD puts many users in a state that is similar to certain symptoms of psychosis ( schizophrenia ). In contrast to psychosis , the user usually knows that the changed perception was brought about deliberately. Such artificially induced states are called model psychosis . The researchers were particularly impressed by the very low dosage and the pronounced effect.

The package insert of Delysid pointed to the possibility of using as Psycholytikum and Psychotomimetikum out. Text excerpt indication: “(a) In analytical psychotherapy to promote mental relaxation by releasing repressed material. (b) Experimental studies of the nature of psychosis: By taking Delysid, the psychiatrist himself is enabled to gain insight into the world of ideas and perceptions of psychiatric patients. "

LSD was first used in what is known as “psychedelic therapy”, for example for people with severe cancer or alcoholics. Their goal was to make the test subjects less fearful or to dissuade them from alcoholism through a shocking ecstatic, strongly religious or mystical experience. In his study on this subject, the pioneer of therapeutic LSD research in Germany, Hanscarl Leuner , speaks of a kind of "healing through religion". Even today, LSD is used in psychotherapy as so-called psycholytic psychotherapy . With all the advantages confirmed by research, this form of therapy also has its downsides, especially because of the power imbalance between the therapist and the therapy client, who has been made highly suggestible by taking LSD. Qualified training and supervision of the therapists is hardly possible because the treatments - apart from special permits - mainly take place illegally.

LSD used to treat alcoholism

Studies in the 1950s found a 50 percent success rate for treating alcoholism with LSD. However, some LSD studies have been criticized for methodological flaws, and different groups gave different results. An article published in 1998 re-examined the work on the subject. It was concluded that the question of the effectiveness of LSD in treating alcoholism remains unanswered. In contrast , a meta-analysis published in 2012 confirmed the results of the original studies and stated a beneficial effect.

LSD attempts by US intelligence agencies and the army

Given the possibility of intoxicating the entire population of the United States with just 10 kilograms of the highly potent psychedelic, research into the use of LSD as a chemical weapon , truth serum, or other purposes began in the early 1950s, under the auspices of the Cold War . Research that the CIA and the Chemical and Biological Warfare Department of the American Armed Forces carried out or had carried out focused on the possibility of using it as a means of mind control and the like. a. to be used in the laboratories of the Edgewood Arsenal . As part of MKULTRA and other projects, LSD was administered to employees without their knowing it; the drug was given to volunteers, drug addicts or prostitutes' clients in so-called safe houses in New York City and San Francisco ; Human experiments on prisoners or on inmates of psychiatric institutions included keeping test subjects under the influence of LSD for several weeks or testing the effects of the drug in combination with electric shocks , sensory deprivation or other drugs. None of these attempts gave any useful results. After the research became public in the mid-1970s, it was discontinued.

LSD in the 1960s

As part of a sub-project of the CIA research program MKULTRA , Ken Kesey , who after his military service worked as a nurse in a mental hospital for some time , took part in LSD experiments there as a test subject. Ken Kesey, like the psychologist Timothy Leary in Berkeley (where research was also carried out in the context of MKULTRA), assumed that LSD could liberate and improve people's personalities by expanding their consciousness and thus also change society in a positive way. He founded a hippie group, the Merry Pranksters , who drove through the USA in a brightly painted school bus, the FURTHER , and held so-called acid tests everywhere, in which lysergic acid diethylamide was used for testing the audience was distributed. The Grateful Dead performed as a band at these LSD happenings . Since LSD was still legal at the time, the idea and practice of LSD use had a strong influence on the hippie era of the late sixties. The journeys of the Merry Pranksters were immortalized in the book Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test by the author Tom Wolfe , who was on the bus for some time . They were an important factor in the creation of the San Francisco hippie movement and psychedelic rock of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

In 1962, Sidney Cohen presented his first warning of the dangers of LSD to the medical community. Cohen's 1960 study of LSD effects concluded that the drug was safe when administered in a supervised medical setting, but by 1962 his concerns about popularization, non-medical use, black market LSD and patients led him to who were harmed by the drug, warned that the spread of LSD was dangerous. In the mid-1960s, Cohen described the LSD state as "completely uncritical" with "the high probability that the knowledge obtained is not at all valid and will overwhelm certain gullible personalities". His alternative to LSD came from the advice he gave to an audience at the end of his life: "I want to recommend them to the sober mind."

Prohibition

When Timothy Leary propagated the mass consumption of LSD in the USA in the 1960s, Albert Hofmann was strongly criticized. After the 1966 ban in the USA and the classification as a non-marketable substance in Germany in 1971, research into LSD-containing therapeutics largely came to a standstill.

As a drug, it was also largely pushed back due to the lack of addiction potential and the strong development of tolerance . Since LSD, unlike most other drugs, is not suitable for daily consumption, the amount demanded is insignificant for the drug trade, and since there is no addiction, users are not forced to pay high prices such as B. to pay for heroin or cocaine .

Current research with LSD

Hallucinogen research has been experiencing a renaissance since around 1990. In December 2007, the Swiss psychiatrist Peter Gasser was approved to conduct a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II dose-response pilot study for psychotherapeutic treatment with LSD in patients with end-stage cancer. The pilot study should “be able to give indications as to whether it is worthwhile and whether it is justifiable to continue researching with LSD-supported psychotherapy, if necessary also on a larger scale with larger numbers of subjects”. The results are promising, but the test group of 12 people is too small to be statistically representative. The study was funded in part by the Swiss Medical Association for Psycholytic Therapy and mainly by the lobby organization Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) .

More recent publications discuss LSD and the non-hallucinogenic 2-bromo-LSD (BOL-148) as possible remedies for cluster headache .

Legal status

In the Federal Republic of Germany, LSD is a non-marketable narcotic due to its appearance in Appendix I BtMG . Handling without permission is generally a criminal offense. Further information can be found in the main article Narcotics Law in Germany .

With the fourth Narcotics Equality Ordinance (4th BtMGlV) of February 21, 1967, which came into force on February 25, 1967, LSD in the Federal Republic of Germany was made subject to the narcotics law provisions of the Opium Act , the forerunner of today's BtMG.

In 1966, lysergic acid diethylamide was banned in the USA. Lysergic acid diethylamide was banned in Austria in 1971.

Lysergic acid diethylamide also falls under the control of the United Nations Convention on Narcotic Drugs (1961) and the Convention on Psychotropic Substances (1971), which were adopted by the United Nations .

literature

- Stanislav Grof : LSD psychotherapy . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-608-94017-0 .

- Albert Hofmann : LSD - my problem child. The discovery of a “miracle drug”. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-608-94300-5 .

- Günter Amendt : The legend of LSD . Zweiausendeins, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-86150-862-5 .

- Annelie Hintzen, Torsten Passie, Beckley Foundation: The pharmacology of LSD: a critical review. Oxford University Press / Beckley Foundation Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-958982-1 .

- Edwin I. Roth: The Post-LSD Syndrome: Diagnosis and Treatment. Author House, Bloomington IN (USA) 2011, ISBN 978-1-4634-1569-3 .

- Andy Roberts: Albion Dreaming. A popular history of LSD in Britain. Cornwall: 2012, ISBN 978-981-4382-16-8 .

- LSD-25. In: Thomas Geschwinde: Drugs: Market forms and modes of action. Third, expanded and revised edition. Springer 2013, ISBN 978-3-662-09679-6 , pp. 59-92.

- Robert Feustel: “A suit made of electricity”. LSD, Cybernetics, and the Psychedelic Revolution. Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3-658-09574-1 .

- Alexander Fromm: Acid is ready! A short cultural history of LSD. Past Publishing , Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-86408-214-6 .

Studies

- DE Nichols: Dark Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD). In: ACS chemical neuroscience. March 2018, doi: 10.1021 / acschemneuro.8b00043 , PMID 29461039 (Review).

- ME Liechti: Modern Clinical Research on LSD. In: Neuropsychopharmacology. Volume 42, number 11, October 2017, pp. 2114-2127, doi: 10.1038 / npp.2017.86 , PMID 28447622 , PMC 5603820 (free full text) (review).

- S. Das, P. Barnwal, A. Ramasamy, S. Sen, S. Mondal: Lysergic acid diethylamide: a drug of 'use'? In: Therapeutic advances in psychopharmacology. Volume 6, number 3, June 2016, pp. 214–228, doi: 10.1177 / 2045125316640440 . PMID 27354909 , PMC 4910402 (free full text) (review).

- Robin L. Carhart-Harris, Suresh Muthukumaraswamy, et al. a .: Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016, S. 201518377, doi: 10.1073 / pnas.1518377113 .

- MB Liester: A review of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) in the treatment of addictions: historical perspectives and future prospects. In: Current drug abuse reviews. Volume 7, number 3, 2014, pp. 146–156. PMID 25563445 (Review).

- T. Passie, JH Halpern, DO Stichtenoth, HM Emrich, A. Hintzen: The pharmacology of lysergic acid diethylamide: a review. ( Memento of March 5, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF) In: CNS neuroscience & therapeutics. Volume 14, Number 4, 2008, pp. 295-314, doi: 10.1111 / j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x . PMID 19040555 (Review).

- HD Abraham, AM Aldridge: Adverse consequences of lysergic acid diethylamide. In: Addiction. Volume 88, Number 10, October 1993, pp. 1327-1334. PMID 8251869 (Review).

Documentaries

- Hofmann's Potion . Documentary, Canada, 2002, 56 min., Director: Connie Littlefield, production: National Film Board of Canada , synopsis .

- The ultimate trip - the discoverer of LSD turns 100. A film by Ralf Breier and Claudia Kuhland, 3sat / ZDF 2006 ( culture time extra ; 35 min).

- The Substance - Albert Hofmann's LSD . Switzerland 2011, directed by Martin Witz .

- Pamela Caragol Wells: LSD - From Trip to Therapy? In: programm.ard.de. January 20, 2011, accessed April 14, 2016 .

- A little bit of LSD - the comeback of the hippie drug LSD . A film by Norbert Lübbers and David Donschen, WDR, 2019 (43:39 min).

Web links

- Lysergide (LSD) (German), European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA)

- InfoFacts: Hallucinogens - LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP. Information from the National Institute on Drug Abuse

- Premiere: How LSD works in the brain. In: science.orf.at. April 12, 2016.

- LSD - Serotonin Intoxicated Brain . Spektrum.de, December 29, 2018

- The good side of LSD. In: Die Zeit , No. 13/2014

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Chemical Research And Development Labs Edgewood Arsenal MD: The Human Assessment Of EA 1729 And EA 3528 By The Inhalation Route . Defense Technical Information Center. July 1, 1964. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ↑ a b c d T. Passie, U. Benzenhöfer: MDA, MDMA, and other "mescaline-like" substances in the US military's search for a truth drug (1940s to 1960s). In: Drug testing and analysis. Volume 10, number 1, January 2018, pp. 72-80, doi: 10.1002 / dta.2292 , PMID 28851034 (review).

- ↑ Entry on lysergic acid diethylamide. In: Römpp Online . Georg Thieme Verlag, accessed on June 5, 2014.

- ↑ a b Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (PDF; 242 kB), Swdrug Monographs, accessed on May 20, 2013.

- ↑ a b c Entry on LSD in the ChemIDplus database of the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) .

- ↑ a b c d data sheet Lysergic acid diethylamide from Sigma-Aldrich , accessed on April 7, 2011 ( PDF ).

- ↑ E. Rothlin: Lysergic Acid Diethylamide And Related Substances. In: Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 66, 1957, pp. 668-676, doi: 10.1111 / j.1749-6632.1957.tb40756.x .

- ↑ LSD profile (chemistry, effects, other names, synthesis, mode of use, pharmacology, medical use, control status) on the EMCDDA website , accessed on July 14, 2018.

- ↑ a b c d e f g European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA): Drug profiles, Lysergide (LSD)

- ↑ a b […] Because of the unpredictability of psychedelic drug effects, any use carries some risk. Dependence and addiction do not occur, but users may require medical attention because of "bad trips". [...] Laurence Brunton, Donald Blumenthal, Iain Buxton, Keith Parker: Goodman and Gilman's Manual of Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2008, ISBN 978-0-07-144343-2 , p. 398. doi: 10.1036 / 0071443436

- ↑ a b C. Lüscher, MA Ungless: The mechanistic classification of addictive drugs . In: PLoS Med . tape 3 , no. 11 , November 2006, p. e437 , doi : 10.1371 / journal.pmed.0030437 , PMID 17105338 , PMC 1635740 (free full text).

- ↑ a b D. E. Nichols: Hallucinogens . (PDF) In: Pharmacology & therapeutics. Volume 101, Number 2, February 2004, pp. 131-181, doi: 10.1016 / j.pharmthera.2003.11.002 . PMID 14761703 . (Review).

- ↑ a b c National Institute on Drug Abuse: InfoFacts: Hallucinogens - LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP.

- ↑ What are hallucinogens? Archived on April 17, 2016 web.archive.org , accessed on April 24, 2016 First published on the website of the National Institute of Drug Abuse in January 2016

- ↑ C. Lüscher, MA: The mechanistic classification of addictive drugs , PLOS Medicine, Volume 3, No. 11, p. E437, published in November 2006, pmid = 17105338, pmc = 1635740, doi = 10.1371 / journal.pmed.0030437

- ^ Nicolas Langlitz: The Persistence of the Subjective in Neuropsychopharmacology. Observations of Contemporary Hallucinogen Research . ( Memento of the original from February 13, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: History of the Human Sciences. 23, 1, 2010, pp. 37-57.

- ↑ a b c d Albert Hofmann: LSD - my problem child. The discovery of a “miracle drug” . DTV, 2006. erowid.org (PDF)

- ^ Alfons Metzner: World problem health. Imhausen International Company mbh , Lahr (Black Forest) 1961, p. 94.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j T. Passie, JH Halpern, DO Stichtenoth, HM Emrich, A. Hintzen: The pharmacology of lysergic acid diethylamide: a review. ( Memento of March 5, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) In: CNS neuroscience & therapeutics. Volume 14, Number 4, 2008, pp. 295-314, doi: 10.1111 / j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x . PMID 19040555 (Review).

- ↑ WH McGlothlin, DO Arnold: LSD revisited. A ten-year follow-up of medical LSD use. In: Archives of general psychiatry. Volume 24, Number 1, January 1971, pp. 35-49. PMID 5538851 .

- ^ Albert Hofmann: LSD. OUP Oxford, 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-963941-0 , p. 44 ( limited preview in the Google book search): The second indication for LSD cited in the Sandoz prospectus for Delysid concerns its use in experimental investigations into the nature of psychoses.

- ↑ SD Brandt, PV Kavanagh et al. a .: Return of the lysergamides. Part I: Analytical and behavioral characterization of 1-propionyl-d-lysergic acid diethylamide (1P-LSD). In: Drug testing and analysis. Volume 8, number 9, September 2016, pp. 891–902, doi: 10.1002 / dta.1884 , PMID 26456305 , PMC 4829483 (free full text).

- ↑ SD Brandt, PV Kavanagh et al. a .: Return of the lysergamides. Part II: Analytical and behavioral characterization of N (6) -allyl-6-norlysergic acid diethylamide (AL-LAD) and (2'S, 4'S) -lysergic acid 2,4-dimethylazetidide (LSZ). In: Drug testing and analysis. Volume 9, number 1, January 2017, pp. 38-50, doi: 10.1002 / dta.1985 , PMID 27265891 , PMC 5411264 (free full text).

- ↑ SD Brandt, PV Kavanagh et al. a .: Return of the lysergamides. Part III: Analytical characterization of N (6) -ethyl-6-norlysergic acid diethylamide (ETH-LAD) and 1-propionyl ETH-LAD (1P-ETH-LAD). In: Drug testing and analysis. March 2017, doi: 10.1002 / dta.2196 , PMID 28342178 .

- ↑ SD Brandt, PV Kavanagh et al. a .: Return of the lysergamides. Part IV: Analytical and pharmacological characterization of lysergic acid morpholide (LSM-775). In: Drug testing and analysis. June 2017, doi: 10.1002 / dta.2222 , PMID 28585392 .

- ^ VJ Watts, RB Mailman, CP Lawler, KA Neve, DE Nichols: LSD and structural analogs: pharmacological evaluation at D1 dopamine receptors. In: Psychopharmacology. 118, 1995, pp. 401-409, doi: 10.1007 / BF02245940 .

- ↑ Lea Wagmann, Lilian HJ Richter a. a .: In vitro metabolic fate of nine LSD-based new psychoactive substances and their analytical detectability in different urinary screening procedures. In: Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2019, doi: 10.1007 / s00216-018-1558-9 .

- ↑ Simon D. Brandt, Pierce V. Kavanagh, Folker Westphal, Alexander Stratford, Anna U. Odland: Return of the lysergamides. Part VI: Analytical and behavioral characterization of 1-cyclopropanoyl-d-lysergic acid diethylamide (1CP-LSD) . In: Drug Testing and Analysis . tape 12 , no. 6 , 2020, ISSN 1942-7611 , p. 812–826 , doi : 10.1002 / dta.2789 ( wiley.com [accessed August 24, 2020]).

- ↑ Matthias Bastigkeit: drugs: a scientific manual. Govi-Verlag Eschborn, 2003, ISBN 3-7741-0979-6 .

- ↑ M. Jang, J. Kim, I. Han, W. Yang: Simultaneous determination of LSD and 2-oxo-3-hydroxy LSD in hair and urine by LC-MS / MS and its application to forensic cases. In: J Pharm Biomed Anal. 115, Nov 10, 2015, pp. 138-143. PMID 26188861 .

- ↑ George K. Aghajanian, Oscar HL Bing: Persistence of lysergic acid diethylamide in the plasma of human subjects. In: Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics . Vol. 5, 1964, pp. 611–614 ( PDF; 229 KB (PDF))

- ^ Damon I. Papac, Rodger L. Foltz: Measurement of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) in human plasma by gas chromatography / negative ion chemical ionization mass spectrometry. In: Journal of Analytical Toxicology . Vol. 14, No. 3, May / June 1990, pp. 189-190. ( PDF; 187 KB )

- ↑ PC Dolder, Y. Schmid, AE Steuer, T. Kraemer, KM Rentsch, F. Hammann, ME Liechti: Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide in Healthy Subjects. In: Clinical Pharmacokinetics . [Electronic publication before going to press] February 2017, doi: 10.1007 / s40262-017-0513-9 , PMID 28197931 .

- ↑ Alexander and Ann Shulgin: LSD . In: TiHKAL. Transform Press, Berkeley 1997, ISBN 0-9630096-9-9 .

- ↑ D. Wacker, S. Wang, JD McCorvy, RM Betz, AJ Venkatakrishnan, A. Levit, K. Lansu, ZL Schools, T. Che, DE Nichols, BK Shoichet, RO Dror, BL Roth: Crystal Structure of an LSD -Bound Human Serotonin Receptor. In: Cell. Volume 168, number 3, January 2017, pp. 377-389.e12, doi: 10.1016 / j.cell.2016.12.033 , PMID 28129538 , PMC 5289311 (free full text).

- ↑ Kim PC Kuypers, Livia Ng, David Erritzoe, Gitte M Knudsen, Charles D Nichols, David E Nichols, Luca Pani, Anaïs Soula, David Nutt: Microdosing psychedelics: More questions than answers? An overview and suggestions for future research. In: Journal of Psychopharmacology. 33, 2019, p. 1039, doi : 10.1177 / 0269881119857204 .

- ^ A b David J Nutt, Leslie A King, Lawrence D Phillips: Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. In: The Lancet. 376, 2010, pp. 1558-1565, doi: 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (10) 61462-6 .

- ↑ Drug Toxicity. Rober Gable, accessed December 14, 2015 .

- ↑ RS Gable: Acute toxicity of drugs versus regulatory status. In: JM Fish (Ed.): Drugs and Society: US Public Policy. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, MD 2006, pp. 149-162.

- ^ Jan Dirk Blom: A Dictionary of Hallucinations. Springer Science & Business Media, 2009, ISBN 978-1-4419-1222-0 , p. 310.

- ↑ Ralph E. Tarter, Robert Ammerman, Peggy J. Ott: Handbook of Substance Abuse: Neurobehavioral Pharmacology. Springer Science & Business Media 2013, ISBN 978-1-4757-2913-9 , p. 236.

- ↑ Review in: AL Halberstadt, MA Geyer: Serotonergic hallucinogens as translational models relevant to schizophrenia. In: The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology / official scientific journal of the Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum. Volume 16, number 10, November 2013, pp. 2165-2180, doi: 10.1017 / S1461145713000722 . PMID 23942028 , PMC 3928979 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ D. De Gregorio, S. Comai, L. Posa, G. Gobbi: d-Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) as a Model of Psychosis: Mechanism of Action and Pharmacology. In: International Journal of Molecular Sciences . Volume 17, number 11, November 2016, p., Doi: 10.3390 / ijms17111953 , PMID 27886063 , PMC 5133947 (free full text) (review).

- ^ JH Halpern, HG Pope: Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder: what do we know after 50 years? In: Drug and alcohol dependence. Volume 69, Number 2, March 2003, pp. 109-119. PMID 12609692 (Review).

- ↑ APA Diagnostic Classification DSM-IV-TR

- ↑ "Severe agitation may respond to diazepam (20 mg orally). “Talking down” by reassurance is also effective and is the management of first choice. Antipsychotic medications may intensify the experience and thus are not indicated. "Laurence Brunton, Bruce A. Chabner, Bjorn Knollman: Goodman and Gilman's Manual of Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 12th edition. McGraw-Hill, 2011, ISBN 978-0-07-176939-6 , p. 1537.

- ^ T. Passie: Psycholytic and psychedelic therapy research: Acomplete international bibliography 1931-1995 . Laurentius Publishers, Hanover 1997.

- ↑ S. Cohen: Lysergic acid diethylamide: side effects and complications. In: The Journal of nervous and mental disease. Volume 130, January 1960, pp. 30-40. PMID 13811003 .

- ^ N. Malleson: Acute adverse reactions to LSD in clinical and experimental use in the United Kingdom. In: The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. Volume 118, Number 543, February 1971, pp. 229-230. PMID 4995932 .

- ↑ P. Gasser: The psycholytic psychotherapy in Switzerland from 1988-1993 A catamnestic survey . (PDF) In: Switzerland Arch Neurol Psychiatr. 147, 1997, pp. 59-65.

- ↑ D. Nutt, LA King, W. Saulsbury, C. Blakemore: Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse . In: The Lancet . tape 369 , no. 9566 , March 24, 2007, p. 1047-1053 , doi : 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (07) 60464-4 , PMID 17382831 .

- ↑ J. van Amsterdam, D. Nutt, L. Phillips, W. van den Brink: European rating of drug harms. In: Journal of psychopharmacology. Volume 29, Number 6, June 2015, pp. 655-660, doi: 10.1177 / 0269881115581980 . PMID 25922421 .

- ^ S. Rolles, F. Measham: Questioning the method and utility of ranking drug harms in drug policy. In: The International journal on drug policy. Volume 22, number 4, July 2011, pp. 243-246, doi: 10.1016 / j.drugpo.2011.04.004 . PMID 21652195 .

- ↑ JP Caulkins, P. Reuter, C. Coulson: Basing drug scheduling decisions on scientific ranking of harmfulness: false promise from false premises. In: Addiction. Volume 106, Number 11, November 2011, pp. 1886-1890, doi: 10.1111 / j.1360-0443.2011.03461.x . PMID 21895823 .

- ^ A b K. R. Bonson, JW Buckholtz, DL Murphy: Chronic administration of serotonergic antidepressants attenuates the subjective effects of LSD in humans. In: Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. Volume 14, Number 6, June 1996, pp. 425-436, doi: 10.1016 / 0893-133X (95) 00145-4 , PMID 8726753 .

- ↑ AM Yu: Indolealkylamines: biotransformations and potential drug-drug interactions. In: The AAPS journal. Volume 10, Number 2, June 2008, pp. 242-253, doi: 10.1208 / s12248-008-9028-5 . PMID 18454322 , PMC 2751378 (free full text) (review).

- ^ PK Gillman: Triptans, serotonin agonists, and serotonin syndrome (serotonin toxicity): a review. In: Headache. Volume 50, number 2, February 2010, pp. 264-272, doi: 10.1111 / j.1526-4610.2009.01575.x . PMID 19925619 (Review).

- ↑ KR Bonson, DL Murphy: Alterations in responses to LSD in humans associated with chronic administration of tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors or lithium. In: Behavioral brain research. Volume 73, Numbers 1-2, 1996, pp. 229-233. PMID 8788508 .

- ^ Robert M. Julien: Drugs and Psychotropic Drugs . Spektrum Verlag, 1997, p. 336.

- ↑ Quoted from: Robert M. Julien: Drugs and Psychopharmaka . Spektrum Verlag, 1997. Source: RS Gable: Toward a comparative overview of dependence potential and acute toxicity of psychoactive substances used nonmedically. In: The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. Volume 19, Number 3, 1993, pp. 263-281. PMID 8213692 . (Review).

- ↑ NI Dishotsky, WD Loughman, RE Mogar, WR Lipscomb: LSD and Genetic Damage. In: Science. 172, 1971, pp. 431-440, doi: 10.1126 / science.172.3982.431 .

- ↑ Jih-Heng Li, Lih-Fang Lin: Genetic toxicology of abused drugs: a brief review. In: Mutagenesis . 13, 1998, pp. 557-565, doi: 10.1093 / mutage / 13.6.557 .

- ↑ MM Cohen, Y. Shiloh: Genetic toxicology of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD-25). In: Mutation Research . Volume 47, Numbers 3-4, 1977-1988, pp. 183-209. PMID 99650 . (Review).

- ↑ Lysergide (LSD): Drug Profile. In: emcdda.europa.eu. Retrieved June 13, 2020 .

- ↑ Drug Commissioner of the Federal Government: Narcotics deaths by cause of death 2010 - country survey . ( Memento of the original from December 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) published on March 24, 2011, accessed online on October 14, 2015.

- ↑ Drug Commissioner of the Federal Government: Narcotics deaths by cause of death 2013 - country survey . ( Memento of the original from February 9, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) published on April 17, 2014, accessed online on October 14, 2015.

- ↑ The drug commissioner of the federal government: Drugs and addiction report . May 2005. bmg.bund.de (PDF)

- ↑ The drug commissioner of the federal government: Drugs and addiction report . May 2009. bmg.bund.de (PDF)

- ↑ European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction: State of the Drugs Problem in Europe. (PDF; 4 MB) 2008, ISBN 978-92-9168-322-2 , p. 57.

- ↑ a b Bromo-Dragonfly Dosage , Erowid.

- ↑ 25I-NBOMe (2C-I-NBOMe) Images , Erowid.

- ↑ Super-LSD sparks drug warning in Adelaide. abc.net.au.

- ↑ 25I-NBOMe sold as LSD. checkit! - Center of Excellence for Recreational Drugs, March 28, 2013.

- ↑ Thomas Geschwinde: Drugs: Market forms and modes of action . Springer DE, 2007, ISBN 978-3-540-72045-4 , pp. 86 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Hans Bangen: History of the drug therapy of schizophrenia. Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-927408-82-4 . Page 10

- ↑ Albert Hofmann: LSD - my problem child. The discovery of the miracle drug. Stuttgart 1993, p. 55.

- ↑ Richard Yensen, Donna Dryer: Thirty Years of Psychedelic Research: The Spring Grove Experiment and Its Consequences. In: Adolf Dittrich, Albert Hofmann, Hanscarl Leuner (eds.): Worlds of consciousness. Volume 4: Importance for psychotherapy. Verlag Wissenschaft und Bildung, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-86135-403-9 , pp. 155–187.

- ↑ Hanscarl Leuner: Hallucinogens. Psychological limit states in research and psychotherapy. Bern / Stuttgart / Vienna 1981, p. 204.

- ↑ Henrik Jungaberle, Peter Gasser, Jan Weinhold, Rolf Verres (eds.): Therapy with psychoactive substances. Practice and criticism of psychotherapy with LSD, psilocybin and MDMA. Bern 2008.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schmidtbauer, Jürgen vom Scheidt: Handbuch der Rauschdrogen. Frankfurt am Main 1998, p. 224ff.

- ↑ Hans-Peter Waldrich : Brainwashing or healing methods. Experience with drug-based psychotherapy. Hamburg 2014.

- ↑ Erika Dyck: Psychedelic Psychiatry: LSD From Clinic to Campus. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

- ^ J. Ross MacLean, Donald C. MacDonald, F. Ogden, E. Wilby: LSD-25 and mescaline as therapeutic adjuvants. In: Harold A. Abramson (Ed.): The Use of LSD in Psychotherapy and Alcoholism. Bobbs-Merrill, New York 1967, pp. 407-426.

- ↑ Keith S. Ditman, Joseph J. Bailey: Evaluating LSD as a psychotherapeutic agent. In: Harold A. Abramson (Ed.): The Use of LSD in Psychotherapy and Alcoholism. Bobbs-Merrill, New York 1967, pp. 74-80.

- ↑ Abram Hoffer: A program for the treatment of alcoholism: LSD, malvaria, and nicotinic acid. In: Harold A. Abramson (Ed.): The Use of LSD in Psychotherapy and Alcoholism. Bobbs-Merrill, New York 1967, pp. 353-402.

- ^ Mariavittoria Mangini: Treatment of alcoholism using psychedelic drugs: a review of the program of research . In: Journal of Psychoactive Drugs . tape 30 , no. 4 , 1998, pp. 381-418 , PMID 9924844 ( catbull.com [PDF; 3.6 MB ]).

- ↑ Teri S. Krebs, Pål Ørjan Johansen: Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. In: Journal of Psychopharmacology . 26, 2012, pp. 994-1002; doi: 10.1177 / 0269881112439253 .

- ↑ Markus Becker: Hallucinogen: LSD helps against alcohol addiction . In: Spiegel Online . March 9, 2012.

- ↑ James S Ketchum: Chemical Warfare Secrets Almost Forgotten . WestBow Press, 2012, ISBN 978-1-4772-7589-4 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Martin A. Lee: Acid Dreams . Grove Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0-8021-3062-4 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Marlon Kuzmick: LSD. In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia . Volume 2, ABC Clio, Santa Barbara / Denver / London 2003, pp. 447 ff.

- ^ Nicolas Langlitz: Better Living Through Chemistry. Origin, failure and renaissance of a psychedelic alternative to cosmetic psychopharmacology. (PDF; 873 kB) In: Christopher Coenen, Stefan Gammel, Reinhard Heil, Andreas Woyke (eds.): The debate about “Human Enhancement”. Historical, philosophical and ethical aspects of human technological improvement . transcript, Bielefeld 2010, pp. 263-286.

- ↑ Jakob Tanner : 'Doors of Perception' vs. 'Mind Control'. Experiments with drugs between the cold war and 1968 . In: Birgit Griesecke, Marcus Krause, Nicolas Pethes, Katja Sabsch (eds.): Cultural history of human experimentation in the 20th century . Suhrkamp , Frankfurt am Main 2009, p. 340-372 .

- ↑ GradeSaver: Tom Wolfe Biography - List of Works, Study Guides & Essays .

- ↑ Barry Graves , Siegfried Schmidt-Joos : The new rock lexicon . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1990, Volume 2, p. 919.

- ↑ Steven J. Novak: LSD before Leary: Sidney Cohen's Critique of 1950s Psychedelic Drug Research. In: Isis. 88, 1997, p. 87, doi : 10.1086 / 383628 .

- ^ KR Bonson: Regulation of human research with LSD in the United States (1949-1987). In: Psychopharmacology. Volume 235, Number 2, February 2018, pp. 591-604, doi: 10.1007 / s00213-017-4777-4 , PMID 29147729 (Review).

- ^ Nicolas Langlitz: The Revival of Hallucinogen Research since the Decade of the Brain. Ph.D. thesis. University of California, Berkeley 2007 (PDF) ; Nicolas Langlitz: Ceci n'est pas une psychose. Toward a Historical Epistemology of Model Psychoses . In: BioSocieties. 1, 2006, p. 2.

- ^ Nicolas Langlitz: The Persistence of the Subjective in Neuropsychopharmacology. Observations of Contemporary Hallucinogen Research . ( Memento of the original from February 13, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: History of the Human Sciences. 23, 1, 2010, pp. 37-57.

- ↑ Peter Gasser: LSD-supported psychotherapy for people with anxiety symptoms in connection with advanced life-threatening diseases . (PDF; 413 kB)

- ↑ The good side of LSD. In: Die Zeit , No. 13/2014

- ^ P. Gasser, D. Holstein, Y. Michel, R. Doblin, B. Yazar-Klosinski, T. Passie, R. Brenneisen: Safety and efficacy of lysergic acid diethylamide-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with life-threatening diseases. In: The Journal of nervous and mental disease. Volume 202, number 7, July 2014, pp. 513-520, doi: 10.1097 / NMD.0000000000000113 . PMID 24594678 , PMC 4086777 (free full text).

- ↑ P. Gasser, K. Kirchner, T. Passie: LSD-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with a life-threatening disease: a qualitative study of acute and sustained subjective effects. In: Journal of psychopharmacology. Volume 29, number 1, January 2015, pp. 57-68, doi: 10.1177 / 0269881114555249 . PMID 25389218 .

- ↑ S. Das, P. Barnwal, A. Ramasamy, S. Sen, S. Mondal: Lysergic acid diethylamide: a drug of 'use'? In: Therapeutic advances in psychopharmacology. Volume 6, number 3, June 2016, pp. 214–228, doi: 10.1177 / 2045125316640440 . PMID 27354909 , PMC 4910402 (free full text) (review).

- ^ R. Andrew Sewell, John H. Halpern, Harrison G. Pope Jr: Response of cluster headache to psilocybin and LSD. In: Neurology. Volume 66, 2006, pp. 1920-1922. PMID 16801660 .

- ^ SJ Tepper, MJ Stillman: Cluster headache: potential options for medically refractory patients (when all else fails). In: Headache. Volume 53, Number 7, Jul-Aug 2013, pp. 1183-1190, doi: 10.1111 / head.12148 . PMID 23808603 (Review).

- ↑ M. Karst, JH Halpern, M. Bernateck, T. Passie: The non-hallucinogen 2-bromo-lysergic acid diethylamide as preventative treatment for cluster headache: an open, non-randomized case series. In: Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache. Volume 30, Number 9, September 2010, pp. 1140-1144, doi: 10.1177 / 0333102410363490 . PMID 20713566 .

- ↑ 4th BtMGlV of February 21, 1967 .

- ↑ Trip to another world. In: Tages-Anzeiger . November 10, 2011.