Life reform

Life reform is the generic term for various social reform movements that have started in Germany and Switzerland in particular since the mid-19th century. Common features were the criticism of industrialization , materialism and urbanization combined with striving for the state of nature . The painter and social reformer Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach is considered to be an important pioneer of life reform ideas . The various movements did not have an overarching organization, but there were numerous associations. Whether the reform movements of the life reform should be classified as modern or as anti-modern and reactionary is controversial. Both theses are represented.

General

The term life reform to denote the social reform movement came up in the last third of the 19th century. The individual movements emerged as a reaction to developments in the modern age , which they saw not as progress but rather as phenomena of decline. Essential to its creation was the fear that modern society with the individual to "civilization damage" and lifestyle diseases lead that could be avoided by a return to "more natural way of life" and healed. “Humans in their civilization-related hardship should not, however, be healed in the banal sense. Life reform wanted his salvation, his redemption. [...] The worldview of the life reform essentially contains a secularized gnostic - eschatological doctrine of redemption. "

Representatives of the life reform propagated a natural way of life with ecological agriculture , vegetarian nutrition without alcoholic beverages and tobacco smoking , reform clothing and naturopathy . In doing so, they reacted to what they saw as the negative consequences of social changes in the 19th century. Spiritually, the life reform turned to new religious and spiritual views, including theosophy , Mazdaznan and yoga .

The architectural form of the life reform first came in settlement experiments such as Monte Verità , later in the garden city movement such as the Hellerau settlement and many others, the most famous representative of which was the reform architect Heinrich Tessenow (1876–1950), and the Bauhaus . The first establishment of a settlement cooperative in Germany was the fruit growing cooperative Eden near Oranienburg in 1893 .

Life reform was a mainly bourgeois-dominated movement in which many women also participated. In physical culture it was about providing people with plenty of fresh air and sun to compensate for the effects of industrialization and urbanization.

Some areas of the life reform movement, such as naturopathy or vegetarianism, were organized in associations and enjoyed great popularity, which is reflected in the number of members. To disseminate their content and principles, they published magazines such as Der Naturarzt or Die Vegetarian Warte .

Part of the reform of life were beyond the nudism (FKK, also naturism ), the gymnastics movement and the free dance . There are references to the land reform movement of Adolf Damaschke , to the free economy of Silvio Gesell , to the early youth movement as well as to other social reform movements and artist groups such as the bridge , the Worpswede artists' colony and the Blauer Reiter .

Individual reform movements

Naturopathy

The basic ideas of the naturopathic movement or the naturopathic movement of the 19th century come from Jean-Jacques Rousseau , who introduced his educational novel Émile or Education in 1762 with the sentence: “Everything that comes from the hands of the Creator is good; everything degenerates in the hands of man ”. He called for a return to a natural way of life, postulated the body's own “natural force”, which should be promoted by hardening , and rejected medication.

The first modern representatives of the naturopathic movement are Vinzenz Prießnitz and Johann Schroth , both farmers and medical laypeople. For the cures named after them, they only used natural remedies such as water, warmth and air and were soon referred to as “miracle doctors”, although they treated the same diseases in completely different ways. An essential feature of the emerging naturopathy was the conviction that the body has self-healing powers that only need to be stimulated and supported. This view went back to Paracelsus . The most famous natural healer of the 19th century was Sebastian Kneipp . So-called natural healing institutions were founded in the German-speaking area . In 1891 131 of them were organized in the umbrella organization of naturopathic associations.

Meyers Konversationslexikon called central views of naturopathy at the end of the 19th century: “She regards the disease processes as healing processes through which the substances disturbing the life act under the signs of fever, inflammation, fermentation and putrefaction, i. H. by decomposition processes, are rendered harmless. In this way, naturopathy has come so far as to explain measles , smallpox and scarlet fever as purification processes used by nature for a certain age, the danger of which was only created by the decrepit human race and by medicine itself. "

In 1883 the German Association for Naturopathy and Public Health Care was founded. In 1900 he renamed himself to the German Confederation of Associations for Natural Living and Healing . In 1889 142 local associations with around 19,000 members were organized in this umbrella organization; in 1913 there were already 885 associations with 148,000 members. The association owned a publishing house that published the journal Der Naturarzt .

The older alternative medical method of homeopathy also experienced increased popularity from 1870, which led to the establishment of numerous homeopathic lay associations in Germany.

In the 1920s, naturopathy lost its overall popularity, the zenith of this movement had passed for the time being. The only exception was the Kneipp Association , founded in 1897 , which had around 65,000 members in the 1960s.

After 1933, the "German Life Reform Movement" has been brought into line and went into the Reich Association of Associations company for natural living and healing method of the NSDAP on. "The National Socialists hoped that the instrumentalization of life reform and natural medicine would increase the efficiency of the German people, their 'racial' health and physical robustness." The NSDAP propagated the inclusion of naturopathic methods in general medicine under the term New German Medicine . The corresponding plans ultimately failed due to resistance from the medical profession.

A German Society for Life Reform , which existed until the 1940s , published the magazine Reformrundschau . From 1941, the Dresden-based research institute of the German Life Reform Movement was also responsible for the research and testing institute for biological remedies opened by Julius Streicher in Nuremberg in 1939 and dealt with different "directions of special, mostly natural way of life and thinking".

From the post-war period, naturopathy became increasingly popular again in Germany. While around half of the population resorted to natural medicines in 1970, over 70% of the population used natural medicines in 2013.

Clothing reform

In the context of the life reform movements in Germany in the second half of the 19th century there were several approaches to reforming clothing, the first considerations relating to men's clothing. There was fierce controversy over the question of which material is particularly beneficial for health. Gustav Jäger thought only wool was suitable, while Heinrich Lahmann advocated cotton and Sebastian Kneipp especially linen. Jäger founded his own clothing company for the normal clothing he designed for men, which was quite successful on the market for several decades, not only in the German-speaking area, but also in England. He founded his own association and published a monthly magazine.

The approaches to reforming women's clothing focused on the abolition of the corset , which was emphatically demanded not only by women's rights activists , but also by some medical professionals. The doctor Samuel Thomas Sömmering had already written an essay in 1788 with the title “On the harmfulness of laced breasts”. In the period that followed, public suspicions increased that the severe constriction led to deformation of internal organs and, above all, to damage to the uterus, favorable constipation and could lead to lacerated liver . Difficulty breathing and a tendency to faint, as well as severely restricted mobility, were actually detectable.

In the USA, Amelia Bloomer was one of the first women to demand a reform dress around 1850 and also wore it for some time. The American reform movement failed, however. The Rational Dress Society was founded in England in 1881, followed by the General Association for the Improvement of Women's Clothing in Germany in 1896, initially with 180 members. In 1900, well-known artists designed so-called artist's clothes without corsets, including Henry van de Velde . However, these models were not intended for mass production. In 1903 the Free Association for the Improvement of Women's Clothing was established , which in 1912 was renamed the German Association for Women's Clothing and Culture . After 1910, haute couture abandoned the corset without making women's fashion comfortable. Only the lack of material and a changed image of women at the time of the First World War caused a major change in women's clothing in the spirit of the reformers.

Nudism

The nudist movement also emerged as part of the life reform movements. The Swiss Arnold Rikli founded a "solar sanatorium" as early as 1853 and prescribed his patients "light baths" without any clothing. In 1906 there were 105 so-called air baths in Germany.

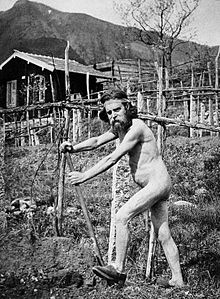

The painter and cultural reformer Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach (1851–1913), who practiced it with his students in the Höllriegelskreuth hermitage near Munich and later on the Himmelhof near Vienna , is considered the real pioneer of nudism, namely outside of hygienic-medical cures . It was through him and against him that the first nudist trial in history took place in 1888. Diefenbach worked on successors such as Heinrich Pudor , Gustav Gräser , Guntram Erich Pohl, Richard Ungewitter and Hugo Höppener- Fidus .

In 1891 Heinrich Pudor published a book called Nackende Menschen. Exult of the future in which he extols nudity as an antidote to the alleged degeneration of people as a result of civilization. "Pudor's combination of health advice, clothing reform, vegetarianism, anti-modernism and anti-Semitism found numerous imitators in the following years." The nudist activist Richard Ungewitter also represented ethnic and anti-Semitic ideas. In 1910 he founded the Lodge for Ascending Life and promoted “strict physical discipline” and “naked choice” with the aim of producing healthy and “pure” offspring. “If every German woman were to see a naked Germanic man more often, so many exotic, alien races would not run after them. For reasons of healthy selection, I therefore call for the nude culture so that the strong and the healthy can mate, but the weak cannot reproduce. "

The leading representatives of nudism decidedly distanced themselves from pornography and free sexuality. "Up until the 1920s there was a broad movement in nudist culture that aimed much more at discipline , body control, self-control, (...) values that were perfectly compatible with Nazi ideology," said the historian Hans Bergemann. The bourgeois nudist representatives strongly criticized the general prudery, but did not represent any liberal views themselves, but redefined the term "immorality". For them the clothed person was immoral. Hans Bergemann:

"You simply said: it is the clothing that sexualises the body and creates the sultry desire first, and you would have to undress naked, that would then reduce the sexual desire or you could better control it."

In a nudist publication it says: “And finally the modern bathing trunks must also be mentioned at this point, this most indecent piece of clothing that can be imagined because it draws the gaze with force on this certain place and points at it with fingers [ ...] "

The supporters of the nudist movement, however, belonged to different ideological directions, even if the most famous publicists were ethnic-national. The nude culture was promoted by the Wandervogel movement, which combined sporting activities. The gymnastics teacher Adolf Koch belonged politically to the camp of socialism and pursued social reform goals within the working class. He also sought sex education , physical strengthening, and medical advice. Koch founded so-called “body schools”, which in the 1920s had significantly more supporters than the bourgeois nudist groups. In 1932 there were around 100,000 organized nudists in the German Reich, around 70,000 of them in physical education.

In 1923, the conservative nudist groups founded the working group of the Bundestag light fighters , which from 1926 called itself the Reich Association for Nudist Culture (RFH). The socialist groups formed the union for socialist lifestyle and nudism . In March 1933 a decree was issued to combat the "nude culture movement". After the RFH had committed itself to the Nazi state, it was brought into line and renamed the campaign ring for völkisch nudist culture .

By far the most extensive collection on the historical and current situation of nudism, the "International Nudist Library" (formerly Damm-Baunatal Collection), is located in the Lower Saxony Institute for Sports History in Hanover.

Nutritional reform

Another part of the life reform was the nutritional reform, which arose in close connection with ideas of naturopathy. Modern vegetarianism in Germany can be seen as a special variant of this movement. The reformers opposed the nineteenth-century dietary changes associated with the modernization of the food industry, falling prices for some products such as sugar and white flour, and the introduction of canned foods and the first ready-made products such as meat extract and stock cubes . The leading proponents of nutritional reforms were medical professionals who saw the modern "civilized diet" as the main cause of many diseases. According to her thesis, only foods that are as natural as possible are really healthy. There was no uniform theory of nutrition, but what the reformers' nutritional concepts had in common was the extensive avoidance of meat, the preference for raw vegetables and whole grain products and the rejection of luxury foods such as tobacco, coffee, alcohol, but also sugar and strong spices . The views of nutrition reformers contradicted the theories of late 19th century nutritional science that viewed animal protein as the main source of energy in human nutrition. The importance of vitamins was still unknown.

Theodor Hahn wrote his book The Natural Diet in 1857/1858 and, a little later, the Practical Manual of Natural Healing , in which he described whole grain products, milk, raw vegetables and raw fruits as optimal foods. The photographer Gustav Schlickeysen (1843-1893), who later emigrated to America and became impoverished there at the age of 50 and died of pneumonia after a cold, described people as fruit-eater and, after being "weak and ailing" as a child, later declined through work had been harmed in the darkroom and hoped to alleviate his symptoms through a vegetarian diet associated with pantheistic ideas, both cooked and animal foods were completely removed. This form of veganism follow the Frutarian . Better known is Maximilian Bircher-Benner , who not only invented Bircher muesli , but also developed his own nutritional theory based on an “energetic approach”: “Sunlight nutrition”. The foods used are interpreted according to their "light value". The ideas of nutritional reform were taken up and disseminated mainly in health clinics. A number of well-known nutritional teachings known as " alternative diets " have their origins in this movement.

Werner Kollath , who published his main work The Order of Our Food in 1942 , also resorted to the work of the nutrition reformers . In it, he described the "civilization food" as inferior "half food", while unprocessed products were "wholesome". He called his nutritional concept whole foods . Vegetarianism developed into an independent movement that also organized itself as a club. An important representative was Gustav Struve whose book plant food. The basis of a new worldview appeared in 1869. Pastor Eduard Baltzer founded the first association for a natural way of life in Nordhausen in 1867 , which in the years that followed was mainly dedicated to nutrition. In 1892 the German Vegetarian Association was established with its seat in Leipzig. In 1912 there were 25 German vegetarian associations with around 5000 members. The health food stores still active in the food trade in Germany and Austria can be traced back to the life reform movement.

Rural communes

As a result of industrialization and urbanization occurred primarily within the educated middle class to "agricultural romantic city hostility" and a regular flight to the country under the slogan "back to nature". Some were satisfied with the creation of allotments or moved to newly emerging garden cities . Others founded with like-minded municipalities in the country with the aim to produce needed food largely self. The author Ulrich Linse writes: "It was an anti-urban revolt of the urban, progressive-minded intelligentsia, it was a rural cult and agrarian utopianism of the urban literary figures". Lens calls this current a form of escapism . Around 1900, the ideas of life reform for healthy lifestyles and nutrition were dominant within the emerging communities, while the idea of cooperatives and ideas for land reform also played a role. He divides the rural communes according to the prevailing worldview into social reforms, folk, anarcho-religious and evangelicals. The Heimland settlement in Northern Brandenburg, which soon disappeared, is to be regarded as ethnic . As a social reformist and anarcho-religious settlement Monte Verità near Ascona. An example of an all-women settlement was the Schwarzerden project near Darmstadt, which is more part of the women's movement than the life reform. Lens attributes the temporary popularity of the settlement idea mainly to the political and economic crises of the German Empire around 1900 and then again after the First World War.

The model of many rural communities was the vegetarian fruit growing settlement Eden , which was founded in 1893 by 18 supporters of the life reform near Oranienburg. The housing estate has been in homes divided and leasehold initially awarded exclusively to vegetarians. For financial reasons, however, non-vegetarians were also accepted from 1901 and the name was changed to non-profit fruit growing settlement . The slaughter of animals and the sale of meat remained prohibited within Eden . Each homestead operated for itself, and there was also cooperative fruit growing as a source of income. In 1894 Eden had 92 members, 22 homesteads were leased, in 1895 there were 45. After a strong decline in membership around 1900, the number rose again. In 1930 there were 230 settlement houses and around 850 residents. The products were sold to health food stores and naturopathic institutions. 1933, some time was ethnically oriented Eden by the Nazis brought into line, but persisted. Even in the GDR, production continued under the Eden brand after 1945 . The cooperative still exists and is active in various business areas.

The artist colonies were a special form of rural communes, for example the Worpswede artists' colony around Paula Modersohn-Becker or in Höllriegelskreuth and Vienna around Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach . The Monte Verità near Ascona in Switzerland, which was founded in 1900 as a life reforming cooperative, became particularly well known . It later split into an economically oriented sanatorium and a group of "secessionists" around the brothers Karl, Ernst and Gusto Gräser . Not only artists and thinkers gathered around the Grass Brothers, they themselves became the subject of poetry, for example by Hermann Hesse and Gerhart Hauptmann . Through them, the “Mountain of Truth” became a citadel for social reformers and opponents of war, and at the same time a gateway for Eastern spirituality. They gave impetus to Dadaism and Expressionism . The Dadaists Hugo Ball , Hans Arp , Hans Richter and Marcel Janco celebrated there in 1917 together with the dancers Rudolf von Laban , Mary Wigman and Suzanne Perrottet an anational “Sun Festival” in front of Gusto Gräser's rock grotto. The mountain is considered the cradle of expressive dance and an early alternative movement . Poets and thinkers such as the dramatists Reinhard Goering and Georg Kaiser , the psychiatrist Otto Gross and the young philosopher Ernst Bloch elevated him to the rank of myth.

Life school

Towards the end of the 19th century and in the first third of the 20th century, reform pedagogy developed, which turned against the alienation of life and the submissive authoritarianism of the prevailing "drills and drills". Education reformers wanted a change in educational theory and learning theory to a change in didactics get that in an action-oriented teaching especially the self-activity , the students at the center. The concepts of the “life school”, as propagated for example by Olga Essig , Franz Hilker , Paul Oestreich or the Bund deciduous school reformers in the 1920s, related to different considerations and attempts of reform pedagogy , such as rural education homes , cohabitation schools , “elastic” unit schools , Work school , production school etc. which, in terms of organization and content, were united in the “new school” to lead to a new “higher quality of human education”.

Life reform in Switzerland

The life reform is seen as a movement mainly originating in Germany. Both the Monte Verità and the Heimgarten near Bülach fruit growing cooperative , which was the model for the non-profit fruit growing settlement in Oranienburg near Berlin, and the Grappenhof near Amden , where Fidus lived for a short time, were not founded by the Swiss. Nevertheless, there is a "Swiss" life reform. It is represented by personalities such as Arnold Rikli , Maximilian Bircher-Benner , Adolf Keller , Ernst Ulrich Buff , Werner Zimmermann and Eduard Fankhauser .

In addition to the places already mentioned, the Friedenfels sanatorium near Sarnen , Fellenberg's Naturheilanstalt in Erlenbach or the Ecole d'Humanité in the community of Hasliberg , and later the Schatzacker settlement in Bassersdorf, are particularly important for the history of life reform .

Well-known life reformers

- William A. Alcott (1798-1859)

- David Ammann (1855-1923)

- Eduard Baltzer (1814-1887)

- Friedrich Eduard Bilz (1842–1922)

- Maximilian Bircher-Benner , doctor and nutrition reformer (1867–1939)

- Wilhelm Bölsche , writer (1861–1939)

- Otto Buchinger , physician (1878–1966)

- Karl Buschhüter , architect and life reformer (1872–1956)

- Carl Buttenstedt (1845-1910)

- Adolf Damaschke , educator (1865–1935)

- Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach , artist (1851–1913)

- Fidus (Hugo Reinhold Karl Johann Höppener; 1868–1948)

- Anna Fischer-Dückelmann , author of The Woman as a Family Doctor

- Gustav Gräser , artist (1879–1958)

- Georg Hiller (1874–1960)

- Adolf Just , author of "Return to Nature!" (1859–1936)

- Gustav Jäger , zoologist and physician (1832–1917)

- Sebastian Kneipp , naturopath (1821–1897)

- Louis Kuhne , naturopath (1835–1901)

- Heinrich Lahmann

- Friedrich Landmann

- Robert Laurer

- Gustav Lilienthal

- gustaf nagel (1874–1952)

- Hans Paasche (1881–1920)

- Arnold Rikli , natural healer (1823–1906)

- Paul Schirrmeister , naturopath (1868–1945)

- Gustav Schlickeysen

- Karl Schmidt-Hellerau (1873–1948)

- Moritz Schreber (1808–1861)

- Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925)

- Johannes Ude (1874–1965)

- Bruno Wille (1860–1928)

See also

- The school of life , series of publications of the federal government decided school reformers

- Paths to strength and beauty

- Waerland food

literature

- Eva Barlösius : A natural lifestyle. On the history of life reform at the turn of the century. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-593-35759-3 .

- Christiane Batz (Ed.): Simply. Naturally. Life: Life Reform in Brandenburg 1890–1933. Berlin 2015.

- Judith Baumgartner, Bernd Wedemeyer-Kolwe : New beginnings, side paths, astray. Search movements and subcultures in the 20th century. Festschrift for Ulrich Linse . Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 2004, ISBN 3-8260-2883-X .

- Claus Bernet : Life reform in Upper Franconia. Hans Klassen and the Neu-Sonnefeld municipality. In: Yearbook for Franconian regional studies. Vol. 67 (2007), pp. 241-354.

- Kai Buchholz, Rita Latocha, Hilke Peckmann, Klaus Wolbert (eds.): The life reform. Drafts for the redesign of life and art around 1900. Catalog for the exhibition at the Institut Mathildenhöhe Darmstadt. Darmstadt 2001, ISBN 3-89552-081-0 .

- Thorsten Carstensen, Marcel Schmid (ed.): The literature of the life reform. Cultural criticism and optimism around 1900 . Transcript, Bielefeld 2016. ISBN 978-3-8394-3334-8 .

- Florentine Fritzen: "Healthier Living". The life reform movement in the 20th century. Steiner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-515-08790-7 .

- Corona Hepp: avant-garde. Modern art, cultural criticism and reform movements after the turn of the century. Modern German history from the 19th century to the present. dtv, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-423-04514-0 .

- Uwe Heyll: water, fasting, air and light. The history of naturopathy in Germany. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-593-37955-4 .

- Diethart Kerbs , Jürgen Reulecke : Handbook of the German reform movements 1880-1933. Hammer, Wuppertal 1998, ISBN 3-87294-787-7 .

- Wolfgang R. Krabbe : Society change through life reform. Structural features of a social reform movement in Germany of the industrialization period. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1974, ISBN 3-525-31813-8 .

- Wolfgang R. Krabbe: "The worldview of the German life reform movement is National Socialism". For the synchronization of an alternative current in the Third Reich. In: Archives for cultural history . 71: 431-461 (1989).

- Ulrich Linse : Barefoot prophets. Savior of the twenties. Siedler, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-88680-088-1 .

- Ulrich Linse (ed.): Back, oh human, to mother earth. Rural communes in Germany 1890–1933. dtv, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-423-02934-X .

- Ulrich Linse: The “natural” life. The life reform. In: Richard van Dülmen (ed.): The invention of humans. Dreams of Creation and Body Images 1500–2000. Böhlau, Vienna 1998, ISBN 3-205-98873-6 , pp. 435–456.

- Sabine Merta: Paths and aberrations to the modern cult of slimness. Diet food and physical culture as the search for new forms of lifestyle 1880–1930. Steiner, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-515-08109-7 .

- Cornelia Regin : Self-Help and Health Policy. The natural healing movement in the German Empire (1889 to 1914). Steiner, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-515-06432-X .

- Christian Rummel: Ragnar Berg. Life and work of the Swedish nutrition researcher and founder of the basic diet. With a foreword by Gundolf Keil . Publishing house Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main / Bern / Vienna / Oxford / New York 2003 (= European University Papers, Series VII, Department B: History of Medicine. Volume 10). At the same time Medical Dissertation Dresden 2001, pp. 163–201.

- Franz Walter, Viola Denecke, Cornelia Regin: Socialist health and life reform associations. Berlin 1991.

- Catherine Repussard, Marc Cluet (ed.): Life reform. The social dynamics of political impotence. Francke, Tübingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-7720-8473-7 .

- Bernd Wedemeyer-Kolwe : "The new person". Physical culture in the German Empire and in the Weimar Republic. Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 2004, ISBN 3-8260-2772-8 ( table of contents and foreword ).

- Bernd Wedemeyer-Kolwe: Departure! - The life reform in Germany . Zabern, Darmstadt 2017, ISBN 978-3-8053-5067-9 .

Web links

- Hans Paasche : The idea of life reform (essay)

- Life reform in Switzerland

- Joachim Radkau : Alternative Modernism: Into the open, into the light! Die Zeit , May 21, 2013

Individual evidence

- ↑ Henning Eichberg: Nude culture, life reform, physical culture - new research literature and methodological questions (pdf)

- ^ Gundolf Keil : Vegetarian. In: Medical historical messages. Journal for the history of science and specialist prose research. Volume 34, 2015 (2016), pp. 29–68, here: pp. 49–59.

- ^ Wolfgang R. Krabbe: Life reform / self reform . In: Diethart Kerbs , Jürgen Reulecke (Ed.): Handbook of German Reform Movements 1880–1933 , p. 74.

- ↑ See also: Eva Barlösius: Naturgememe Lebensführung

- ^ Bridge and the Life Reform Exhibition from July 2 to October 9, 2016 in the Buchheim Museum , press release from July 2, 2016

- ↑ Renate Foitzik Kirchgraber: Life Reform and Artist Groups around 1900. Dissertation at the University of Basel 2003, p. 53 ff.

- ↑ a b c Wolfgang R. Krabbe: Naturopathic Movement . In: Kerbs / Reulecke, p. 77 ff.

- ↑ Article Naturopathy . In: Meyers Konversationslexikon , ca.1895

- ^ Krabbe, Naturheilbewegung , p. 82

- ↑ Franconia, go ahead again! In the struggle for public health. Opening of an examination institute for biological remedies by Julius Streicher. In: Franconian daily newspaper. 18 January 1939, p. 8.

- ^ Gundolf Keil: Vegetarian. 2015 (2016), p. 49.

- ↑ Oncology Aspects ( Memento from October 17, 2013 in the Internet Archive ): Naturopathy increasingly popular and valued. Data based on the Allensbacher market and advertising media analysis .

- ^ A b c Karen Ellwanger, Elisabeth Meyer-Renschhausen: Clothing reform . In: Kerbs / Reulecke, pp. 87 ff.

- ↑ a b Rolf Koerber: nudism . In: Kerbs / Reulecke, p. 105.

- ↑ a b c d Arna Vogel: When the covers fall - History of nudism ( Memento from March 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Koerber: nudism . P. 103 ff.

- ↑ a b Judith Baumgartner: Nutritional reform . In: Kerbs / Reulecke, p. 15 ff.

- ^ Karl Eduard Rothschuh : Naturopathic Movement, Reform Movement, Alternative Movement. Stuttgart 1983; Reprint Darmstadt 1986, pp. 97-99.

- ^ Gundolf Keil: Vegetarian. 2015 (2016), pp. 54 and 59.

- ^ Judith Baumgartner: Vegetarianism . In: Kerbs / Reulecke, p. 127 ff.

- ↑ a b c Ulrich Linse: rural communes in Germany 1890-1933 (excerpt)

- ↑ Werner Onken: Model experiments with socially responsible soil and money (pdf) ( Memento from October 7, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ George L. Mosse : The Volkische Revolution. About the spiritual roots of National Socialism . Hain, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-445-04765-0 , pp. 123f.