Kurmainz

Kurmainz was the territory ( ore monastery ) administered by the electors and archbishops of Mainz in the Holy Roman Empire . Along with Kurköln and Kurtrier, it belonged to the three spiritual electoral principalities. The three Rhenish archbishops, together with the Count Palatine near Rhine , the Margraves of Brandenburg , the Dukes of Saxony and the Kings of Bohemia, had the sole right to elect the Roman-German King and Emperor since the 13th century . Since 1512 Kurmainz belonged to the Kurrheinische Reichskreis .

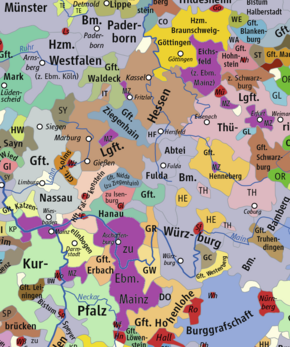

The territory of the Electorate and the Archdiocese of Mainz

The boundaries of the electorate and the archbishopric did not coincide geographically. In the electorate (the archbishopric ), the Archbishop of Mainz was a direct imperial prince and thus secular ruler, and in the archbishopric the pastor .

In his capacity as metropolitan, the Archbishop of Mainz included the ecclesiastical area of supervision of the Mainz church province , which in the High Middle Ages included the suffragan dioceses of Worms , Speyer , Constance , Strasbourg , Augsburg , Chur , Würzburg , Eichstätt , Paderborn and Hildesheim .

The Archdiocese of Mainz was a contiguous area and extended from the Hunsrück over the northern Odenwald , the Vogelsberg to Einbeck and the Saale .

In contrast to the diocese, the Electorate of Mainz (Kurmainz) was very fragmented and comprised as of 1787

- the Lower archbishopric, including Mainz , some places south of the city, the Rheingau , the area around Bingen , the Office Oberlahnstein and a long strip of territory north-east of Mainz, which extends from maximum am Main in the Taunus into it up to the castle Koenigstein extended belonged and

- the Obere Erzstift, an area from Seligenstadt in the north over the Bergstrasse and the Odenwald to Heppenheim , Walldürn and Buchen in the south, divided in two by the Main , with the administrative capital Aschaffenburg .

In addition, there were some Hessian offices such as Amöneburg and Fritzlar , the Erfurt State , the Eichsfeld State and shares in the counties of Rieneck (in the Franconian district), Königstein (in the Upper Rhine district), Gleichen and in the Lower County of Kranichfeld .

The area of the electorate totaled 6150 km², according to other information also 8260 km², depending on the conversion key of the 170 square miles that are generally given for the territory. The population was around 350,000 in the 18th century; 30,000 people lived in the city of Mainz itself at that time.

The historical development of the electorate and archbishopric

The Archbishopric of Mainz was finally established in 780/81. Up to the 13th century its development was marked by the steady rise of the Archbishops of Mainz to the first ecclesiastical and secular imperial princes.

The late Middle Ages was the phase of territorialization or the expansion of the holdings of the electoral state and the archbishopric. This only ended in 1462 with the collapse in the Mainz collegiate feud .

During the Reformation , Mainz suffered the heaviest territorial losses, which it was only able to make up to a minor extent during the Counter Reformation (as a member of the Catholic League ) and the Thirty Years' War .

From the Peace of Westphalia to the secularization of 1803, the electoral state changed only slightly in territorial terms. It froze and with it the final loss of its earlier imperial political importance.

The population groups in the spa state

Four population groups can be identified in Kurmainz. The largest group in number were the farmers who were in a dependent status. All the arable land they cultivated belonged to the privileged classes, that is in this case to the elector, the cathedral chapter , the monasteries and imperial knights, who received a lucrative income from the various taxes that the peasants had to pay, especially the tithe .

Undoubtedly the most influential section of the population were the Imperial Knights , who were unrivaled as members of the nobility in Kurmainz. Apart from them there was only the service aristocracy , but they were counted among the bourgeoisie. The imperial knights were directly subordinate to the empire , that is, not subordinate to the sovereignty and jurisdiction of the elector, but were directly subordinate to the emperor. Most of the electors themselves belonged to this imperial knighthood after the Reformation. As a privileged class, the Imperial Knights were exempt from all taxes and duties. All twenty-four benefices of the cathedral chapter, about 130 official posts in the electorate, plus about sixty-five honorary posts at the Mainz court, high posts in the military and the occupation of the electoral bodyguard were exclusively reserved for them.

The last population groups to be mentioned here are the citizens and the residents or tolerated people, who are mainly concentrated in the cities, especially in Mainz.

The bourgeoisie included merchants, businesspeople and master craftsmen, i.e. members of a guild , as only these received citizenship. The citizens had special rights and privileges, for example personal freedom, they did not have to do labor or military service and could be elected to municipal bodies. Under-seated and tolerated, the latter were the Protestants and protective Jews , one understood the immigrants in Mainz, who were allowed to settle there for a certain period of time and upon revocation and who were allowed to practice their profession, but could not acquire citizenship.

The economy

The city of Mainz was at the center of the economic life of the Electorate of Mainz. Mainz was less of a factory town like Frankfurt than it was more of a distribution center for goods. There was fertile land around the city, and extensive agricultural production provided wine, tobacco, hemp, millet, fruit, nuts and, above all, grain for export. Wood was also exported from the Taunus and Spessart forests . Also worth mentioning in this context is the Rheingau , which, then as now, was considered one of the best wine-growing regions. The city of Mainz, like Cologne, had stockpiling rights since 1495 , which concerned trade on the Rhine.

Goods that passed through the city had to be unloaded and offered for sale for three days before they could be loaded onto Mainz ships and transported to their final destination. The electors were very interested in maintaining this privilege, as it secured them the fees incurred as income for the state treasury. The old department store on the fire, which was demolished in the 19th century because it had lost its function and was becoming dilapidated, was evidence of this.

At the end of the 18th century, the city's economy was still dominated by the craft guilds, which, however, had been subject to princely absolutism since 1462. A member of the city council appointed by the elector, and two police commissioners from 1782, had to be present at all guild meetings. No decision could be made without the consent of the elector. So the guilds were basically just state organs. Overall, Mainz was economically pushed into the background by Frankfurt, among other things through the abolition of urban freedoms after 1462.

It was only with the mercantilist policy of Elector Johann Friedrich Karl von Ostein (1743–1763) that trade experienced a revival. Between 1730 and 1790 there was both an economic upswing and population growth in Kurmainz.

Elector and cathedral chapter

The position of the elector in the empire

In addition to his functions in the Mainz electorate and archbishopric, the elector also had a prominent position in the Roman Empire . He was chairman of the college of electors , that is, he summoned the six other electors to Frankfurt am Main to elect the new king . There he presided over the election of the king and deliberations on electoral surrender . He also took the consecration and anointing before the new king. In addition, the Elector of Mainz was Arch Chancellor and head of the Reich Chancellery , formally the most important man in the Reichstag . He exercised control over the Reichstag archives and held a special position at the Reichshofrat and Reichskammergericht . As the prince and director of the district, he was responsible for the management of the electoral-Rhenish district . Most of these functions, however, were more representative than they gave the elector political weight.

The Mainz Cathedral Chapter

The Mainz cathedral chapter had 24 benefices and its own domain, which was directly subordinate to the emperor and for which it was not responsible to the elector. The area included large estates, including the city of Bingen and seven other important localities. In addition, the chapter had lands in the electorate itself and in other principalities. These possessions secured a large income for the cathedral chapter, which was estimated to make up one fifth of the total income of the Mainz archbishopric.

Some of the members of the chapter had additional income that resulted from the fact that they sat in other chapters or collegiate colleges or held secular offices in the electorate that were reserved for them.

The cathedral chapter was ruled by the imperial knights. Its members had to belong to one of the three imperial knight circles, i.e. the Franconian, Swabian or Rhenish circles, and had to prove that their 16 great-great-grandparents were all of German knightly origin. The gaps in the cathedral chapter were filled by co-opting , that is, the nominees were appointed by the canons and the elector. In practice, this practice resulted in relatives being appointed over and over again and the chapter being dominated by a small group of families. The main task of the cathedral chapter was the election of the archbishop and elector and, in the event of the death of an elector, the administration of the electoral state until a new one was elected. His influence was mainly secured by the electoral capitulations , in which the old and new privileges of the cathedral chapter were determined, on which the respective elector was then sworn in when he took office.

The election surrenders

The electoral capitulations were the constitution of the electorate , insofar as one can speak of such a thing here. They reached their most complete form with the capitulatio perpetua of 1788, drawn up by the chapter on the occasion of the election of the coadjutor (= official assistant) Dalberg. This capitulation (which never came into force) was intended as a kind of constitutional law, which not only the archbishop and elector, but also servants and officials were supposed to swear. In terms of content, the claim of the chapter was laid down to be the estates of the electorate; since the Peasants' War of 1524/25 there were no estates in Kurmainz (the only exception were the estates of the Eichsfeld ).

In addition, it was stated that the elector could not sell or pledge any land or incur any debts without the consent of the Chapter. He was committed to maintaining the Catholic religion and preferring Catholics when filling civil servants, maintaining good relations with the Pope and the connection with the Habsburgs, as well as eliminating apostates, i.e. heretics . The election surrenders did not give the chapter a legislative veto . His approval was only required in financial matters, i.e. taxes, tax levies, and the creation of new taxes.

In the 18th century, the electoral capitulations lost in importance as they were officially banned by the Pope in 1695 and by the Emperor in 1698. However, Elector Lothar Franz von Schönborn (1695–1729), who in this case was obviously on the side of the chapter, was able to obtain a papal letter exempting Mainz from the ban on electoral surrenders. When, in 1774, before the election of Elector Friedrich Karl Joseph von Erthal , the influence of this prohibition was felt for the first time, the cathedral chapter began to work out an official main surrender and a kind of secret secondary surrender, in which all articles were summarized that could possibly involve the Pope or provoked Kaisers.

Central administrative bodies

The Councilor

The court council was the central administrative body of the electoral state. The origins of the councilor are not clear. Until Albrecht von Brandenburg's term of office (1514–1545) there was no court councilor with regular rules of procedure. At that time the administration took place within the framework of the court. Elector Jakob von Liebenstein (1504–1508) issued the first known court rules around 1505. Election capitulations show that a council must have existed as early as 1459. However, it was disorganized and with no specific participants.

1522 taught Elector Albrecht a resistant or parent council and gave the Council College as a solid form. It consisted of 13 members, 9 of whom were appointed by the elector, namely court master, chancellor, marshal, the two members of the cathedral chapter to be sent, two legal scholars and two representatives of the nobility. The other four were sent by prelates and nobility from the lower and upper regions. In 1541 a new regulation followed for the council and chancellery, which also regulated the competencies between local administration and central administration. This order became decisive for the later development of the body. The council was therefore both a central administrative authority and a court, as it ruled on appeals against judgments of the castle courts or acted as a judge in difficult processes. The Council also provided advice on criminal matters.

The most important office in the council was that of the court master. The Hofmeister was in charge of finance and local administration, and he also conducted diplomatic negotiations. Over time, however, the day-to-day management of the princely household passed to the steward and of government affairs to the chancellor.

As a rule, the chancellor was a lawyer of bourgeois origin, and although the electoral capitulations up to 1675 provided for the office to be occupied by a clergyman, from the mid-16th century onwards the chancellors were mostly lay people.

The college was composed of noble and learned councilors, their term of office was limited to six years in the 16th century. The learned councilors perceived the daily work of the court councilors and were more important than the aristocratic councilors, as they were only involved in certain tasks on a case-by-case basis. The council did not have a permanent seat, it always followed the court and thus met in Mainz as well as in Johannisburg Palace in Aschaffenburg . At the beginning of the 17th century the personnel structure changed. In 1609 the director in judicialibus (who was responsible for the processes of the archbishopric) and the court president (from 1693 president of the court council) joined the court master and marshal, who had formed the presidium up to that point.

The Thirty Years' War hampered further development of the administration and thus also of the court councilor. It was not until 1674 that the committee was redesigned, including the creation of the office of director of the chancellery, who had to relieve the chancellor. The other innovations were largely experimental in nature. This included the establishment of a war conference in 1690, which was raised to the rank of an independent authority as a court war council in 1780, which, however, in view of the small military power of the electoral state, was more for reasons of prestige. However, the development in the area of criminal justice was significant. From the end of the 17th century, the councilor gradually took over the criminal trials. In 1776 its own criminal senate was established. Since at the same time a government justice senate was established as a disciplinary court for civil servants and an arbitration tribunal, the court council itself only had administrative jurisdiction afterwards.

Since the 17th century the council members were appointed for life, but could - with the exception of the court (council) president, who was secured by election surrender - be dismissed by the elector. In the 18th century, the President of the Councilor ousted the Hofmeister from the management of the Councilor. Although he was a member of the council until 1774, he only appeared on ceremonial occasions and otherwise transferred his work to the Secret State Conference. The marshal disappeared entirely from the administration.

In 1771 there were 31 aristocratic and 28 learned court councilors, in 1790 a total of 49 members.

Secret Council, Cabinet Conference and Secret State Conference

The body of the Secret Council originally had the character of a private meeting away from official institutions. It was used by the elector to discuss more or less secret matters in a circle of less confidants, including some councilors and high court officials. In the new edition of the Hofratsordnung of 1451, Elector Albrecht von Brandenburg had already kept open the option to consult members of the Hofrat for confidential deliberations. According to this practice, not much is known about the work of the Secret Councils during this period.

That only changed with the increasing involvement in big politics in the 17th century. The Secret Council met regularly in the 1640s and had its own area of responsibility, which primarily included questions of foreign policy. The organization was similar to that of the court councilor.

After the death of Johann Philipp von Schönborn in 1673, the Secret Council lost its importance again. In the 1730s, however, conference ministers (conference ministers) were reappointed, which in 1754 under the chairmanship of the elector became a permanent institution as a secret cabinet conference and since 1766 officially appeared in the court and state calendars . In 1774, Friedrich Karl Joseph von Erthal dissolved the body again, but re-established it a year later as a Secret State Conference. It consisted of the Minister of State and Conference as well as five trainee lawyers, two of whom carried the title of Privy Council of State. In 1781 a clerk for spiritual matters was added. The committee exercised considerable influence on the elector. From 1790 there were four ministers of state and conference, which makes the state conference appear oversized compared to the actual importance of the electoral state. It was thus an example of the fact that the elector's urge for validity always flowed into the shaping of the authorities and bodies of the electoral state.

The court chamber

It is not clear how long a central camera administration has existed in the archbishopric. Before the 16th century, only the office of chamber clerk existed as a minor charge. The reform of Albrecht von Brandenburg in 1522 determined that the court councilor had to take over the financial management. However, this regulation only lasted for a short time. In the 16th century, the management of the finances was again entrusted to the clerk, who ran the accounting and rent chamber, which was later called the court chamber. The main task was the supervision of the archaeological domains as well as the income from customs offices and cellars.

Between 1619 and 1625 the court chamber was converted into a collegial authority, headed by a chamber president from the cathedral chapter. The chamber clerk held the title of chamber director from 1667 and was responsible for running the business, the chamber president only represented. The committee consisted of four to five, until 1740 twelve court chamber councilors. The area of responsibility extended in addition to the original areas also to the participation in the management of the state manufactories, mines and salt works . Elector Johann Philipp von Schönborn withdrew her influence on hunting and forestry for a short time. With the establishment of the War Conference in 1690, the military, which also fell under the jurisdiction of the Chamber, was given its own administration, which was initially dependent on the Court Chamber.

In the 18th century, an auditing system was finally introduced, the invoice revision or invoice deputation. In 1788 it received the status of an independent authority as an auditing chamber. There was no cash separation between farm supplies and state administration until the end of the state.

With the exception of the management functions, the members of the Hofkammer were commoners. Despite higher salaries than in the court council, the offices in the court chamber were not coveted. Its origins were attached to it as a sub-senior authority, the members of which had worked their way up as simple people.

The court court

The establishment of the court court also went back to the reform activities of Elector Albrecht of Brandenburg. Deficiencies in the judiciary and requirements of the Reich Chamber of Justice regulations from 1495 prompted him to draw up a court court order, the final version of which from 1516 was confirmed by Emperor Charles V on May 21, 1521 . It applied to the entire archbishopric with the exception of Eichsfeld, for which an intermediate instance was created, and the city of Erfurt, which at that time was revolting against the archbishopric rule. It was not until 1664 that the court court order came into force there.

In contrast to the court chamber and court councilor, the court court did not follow the respective whereabouts of the court, but had its permanent seat in Mainz. It acted in both first and second instance. The jurisdiction in the first instance encompassed processes of particular interest to the archbishop, processes of the nobility, the civil service and all persons with an excluded place of jurisdiction, including foreigners who turned to the court. Furthermore, the elector and court councilor were able to refer all processes to the court court. However, the main task of the court was to function as an appellate authority . It ruled on all appeals against judgments handed down by lower courts, even those passed by Jews in the first instance before the rabbi. In addition, the court judged abuse of law such as denial of law , procrastination or judicial partiality. On the other hand, the court was not responsible for trials of clergymen, officials and servants of the court as well as of people who lived within the castle spell. The vicariate office was responsible for the clergy in the first instance, and commissioners appointed from the ranks of the cathedral capitals in the second instance. The court servants and officials had their place of jurisdiction in the first instance at the Oberhofmarschallamt as the “highest castle court” and in the second instance at the court councilor. In the 17th century, the court court was also deprived of commercial and construction matters. As already mentioned, criminal justice fell under the jurisdiction of the court councilor (from 1776 under that of the criminal senate). The military also had its own jurisdiction.

In principle, the court court was only staffed with staff who did not work at any other authority. Only the office of the head judge was combined with other offices like that of the Vice-Cathedral in the Rheingau , so that it degenerated into a sinecure . Since the end of the 17th century, the presidency was therefore exercised by a court president, which, however, also became a sinecure from 1742. The chair was now taken over by one of the learned assessors at the court, who accepted the title of court director. Originally there were ten such assessors, five nobles and five scholars, all of whom were ranked on an equal footing with court councilors from 1662 onwards. In the course of time, however, the aristocratic assessors no longer fulfilled their obligations, which is why the work of the court was essentially done by the bourgeois court judges. That only changed when the court became a transit station for the Councilor in the 18th century. In 1786 there were 30 assessors.

Originally the court court was a so-called quarter court. So the Court only pronounced judgments four times a year. Because this turned out to be impractical, interim judgments were later published twice a week, which were converted into final judgments at the regular meeting at the end of the quarter. It was not until 1662 that there was a four-week cycle, from 1746 onwards the proclamation took place at the discretion of the judges.

For a long time there was no third-level court over the court. Revisions were submitted to the Reich Chamber of Commerce, subject to the rights of the Elector. A court of appeal was not established until 1662, which meant that there was no longer any possibility of appealing to the Reich Chamber of Commerce. The appeal court's operations soon came to a standstill, however, and it wasn't until 1710 that the court was given its own rules. The members were mainly members of the court council, with the chancellor or vice-chancellor as president. Only in 1776 did it have its own director again. It was occupied by six to eight judges.

The officialdom

The officials of the Mainz state were treated in a patriarchal manner. The highest civil servants were paid very high salaries, while the others were paid low, which meant that the subjects had to pay very high fees for using the authorities, which served the civil servants as ancillary income. So the officials not only had the interests of the state in mind, but also their own benefit, which the administration suffered from. In the course of the development of the electoral state, the cathedral chapter secured high posts for itself with the help of electoral surrenders and thus influence on the administration, so that at least nothing could happen without its knowledge. Overall, the administrative apparatus, despite some structural deficiencies, brought advantages only to the elector, who thus had an instrument at his disposal that the chapter had nothing to counter.

The relationship between the elector and the cathedral chapter in the emerging absolutism

The direct imperial position of the canons, the existence of the electoral surrender and the fact that certain offices were reserved for them in the state ensured the chapter privileges, immunities and influence on politics. In any case, one could have opposed a tyrannical elector. But all this also led to a certain dualism between the elector and cathedral chapter with regard to power in the electoral state. In practice, however, the elector and his closest circle of advisors alone made the political decisions. Regular tax revenues and extensive goods enabled him at least to have a relatively independent domestic policy.

As civil servants in the administration, the canons had to obey the orders of the elector in order not to lose their position. So they were forced to submit to the elector rather than being able to afford to represent the interests of the chapter too strongly. This was especially true when the canons sought to accommodate family members in the administration.

On the other hand, the elector and cathedral chapter mostly came from the same social class and thus interest group. In this respect, equilibrium and moderation were considered a rule of conduct between the two and were also a prerequisite for maintaining the form of government. The electors had a domestic political interest in accommodating as many relatives as possible in the chapter, one of whom might succeed and thus stabilize their own mode of government. With this aim, the electors could not ruthlessly disregard the interests of the cathedral chapter.

There was a kind of symbiosis between the elector and cathedral chapter, both were dependent on each other, both tried to limit the power of the other, although in the 18th century one can determine a dominance of the electors, especially the enlightened ones, above all because they were the only authorities and The official apparatus as an instrument of power benefited. Perhaps the term elective monarchy best applies to the Electoral Mainz of this century.

It is worth mentioning in this context that both the elector and cathedral chapter were usually supporters of the Habsburg monarchy, since Kurmainz, as a spiritual territory, was dependent on the survival of the empire. This in turn gave the Habsburgs the opportunity to influence the election of the Elector of Mainz, mainly through financial means.

Territorial authorities of the administration

The vice domes

The Vizedom was originally an office of the central authority. Since the territory of the archbishops (there was no electoral state at the time) developed in several centers, it became necessary to administer each of these centers separately. Archbishop Adalbert I of Saarbrücken (1112–1137) therefore set up a vice cathedral from 1120 for the centers of Mainz-Rheingau, the Vizedomamt Aschaffenburg , Eichsfeld and the Hessian exclave as well as for Erfurt . They formed the middle instance between central power and officials.

There was no clear demarcation of the districts of the Vizedome. The authority of the Mainz vice cathedral was concentrated after Archbishop Siegfried III granted city freedom . von Eppstein (1230–1249) mainly on the Rheingau. After the city fell back to the archbishop in 1462, two vice domiciles were created, one for the city ( vice cathedral in the city of Mainz ) and one for the surrounding area ( vice cathedral except for the city of Mainz ). The Vice Cathedral Office Rheingau existed until the end of the electoral state.

The area of competence of the Aschaffenburg Vizedom was originally the territory around Main , Tauber (including Kurmainzisches Schloss Tauberbischofsheim ), Spessart and Odenwald . However, the area shrank significantly over time. From 1773 the office was no longer occupied and the management of the business was transferred to a vice cathedral director in 1782.

The Vizedom at Rusteberg Castle was responsible for Hesse and the Eichsfeld . However, as early as 1273, Hesse had its own regional administration. At that time the office was already in the hands of the Hansteiners as a hereditary fiefdom and developed into a sinecure. In 1323 the noble family sold the office to the archbishop. Therefore, in 1354 a Landvogtei for Hesse, Thuringia and the Eichsfeld was set up on the Rusteberg, which was already divided into a Landvogtei district for Hesse and Westphalia as well as for Eichsfeld, Thuringia and Saxony in 1385. In 1732 a governor took the place of the bailiffs (senior officials).

In Erfurt , the office of the vice cathedral had become hereditary shortly after its establishment in the first half of the 12th century. As in the case of Rusteberg, the feudal takers sold the office to the archbishop (1342). After that, archbishop provisional officers officiated; the office of vice cathedral did not go under, but lost its importance. It was not rebuilt in its original meaning until 1664. In 1675 it was converted into a Lieutenancy.

In contrast to the vice domains in Rheingau and Aschaffenburg, the Lieutenancies on Eichsfeld and in Erfurt comprised an extensive body of authorities. This is also expressed in the designations as the Electoral Mainz Eichsfeld State and the Electoral Mainz Erfurt State .

The areas of responsibility of the Vizedome mainly comprised judicial and military matters, with different priorities. On the other hand, the Vizedom was released from camera matters - the supervision of goods and income - early on (from the 14th century) through the establishment of a camera administration.

Offices and senior offices

The growing territory of the archbishop's rulership soon made it necessary to undertake further subdivisions into manageable districts after the division into the four areas of the Vizedome. This led to the establishment of the offices , the center of which was often the castles, which is why burgraves often acted as officials until the 16th century. That is how long it took to give the office structure a fixed form. Fluctuations in official responsibilities (e.g. through exchange or pledging) as well as the financial and military dependence of the archbishop, who was notoriously numb due to the monastery schisms, on the burgraves had prevented this beforehand.

The Kurmainzische Army

Since the Peace of Westphalia, the electoral state had also had a standing army that was held up to defend the territory. The main point of defense was the Mainz fortress , which was gradually expanded into one of the largest and most important imperial fortresses.

Witch trials in Kurmainz

Mainz was not one of the areas of the first witch trials in the 15th century, and Archbishop Berthold von Henneberg, like many others , ignored the support of the inquisitors Heinrich Institoris and Jakob Sprenger for imprisonment and punishment demanded by Pope Innocent VIII in 1484 in the papal bull Summis desiderantes affectibus ( not burning) of witches. However, throughout the sixteenth century there were repeated complaints of defamation, which occasionally led to lawsuits with different outcomes.

That changed from 1594 when, under the tolerance of Archbishop Johann Adam von Bicken and his successor Johann Schweikhard von Kronberg, a large number of witch trials with over 1000 executions took place, particularly in the Oberstift (the Electoral Mainz area around Aschaffenburg) . There were 650 executions under Johann Adam von Bicken in the years 1601 to 1604 and 361 executions under Johann Schweikhard von Kronberg until 1626. Under the next Prince-Bishop Georg Friedrich von Greiffenclau , 768 other people were executed for witchcraft from 1626 to 1629. From 1604 to 1629 , documents relating to the deaths of 1779 people as victims of witch persecution have been preserved for the Mainz Archbishopric . Two of the victims in Aschaffenburg were the carp hostess Margarethe Rücker and the cross-cutter Elisabeth Strauss, who were beheaded and burned on December 19, 1611. In Flörsheim, three adolescent siblings were executed for alleged witchcraft in 1617: Johann Schad, Margreth Schad and Ela Schad .

Archbishop Johann Philipp von Schönborn , as one of the first German imperial princes, broke the witchcraft madness in the middle of the 17th century by making the occasional witch trials more difficult through ordinances and finally banning them.

Similar massive persecutions of witches as in the ore monastery Mainz between 1594 and 1618 can only be proven in southern Germany in the witch trials series of the high monasteries Bamberg and Würzburg as well as in Eichstätt and Ellwangen .

The last electors of Mainz in the 18th century

Franz Ludwig von Pfalz-Neuburg (1729–1732)

Since the coadjutor Franz Ludwig von Pfalz-Neuburg only ruled as elector for three years, it is difficult to characterize his policy. He drew mainly from the work of his predecessor Lothar Franz von Schönborn . The only reforms that deserve special mention here are to improve the training of priests and judges. There were no conflicts with the cathedral chapter, as it had previously discussed the election surrender and thus ensured compliance.

Philipp Karl von Eltz-Kempenich (1732–1743)

Philipp Karl von Eltz was cathedral choirmaster in Mainz and was elected elector on an imperial recommendation in 1732. He followed a traditional Habsburg course and had been very committed to the recognition of the Pragmatic Sanction , which regulated succession in Austria. Only when he voted in 1742 to elect the Bavarian Elector Karl Albrecht as German Emperor did the relationship with Austria deteriorate. Philipp Karl had attended the Collegium Germanicum in Rome for two years and thus had a much better spiritual education than other electors. This was especially evident in the fact that he performed his spiritual duties more intensively. He also had twenty years of experience as government president in secular affairs. Particularly noteworthy here is the reduction of the debt burdens of the state.

Johann Friedrich Karl von Ostein (1743–1763)

The era of enlightened absolutism began in Mainz with Johann Friedrich Karl von Ostein . In practice, however, he was not the ruler of the electorate, but his chancellor Anton Heinrich Friedrich von Stadion , who had already held high offices under Johann Friedrich's two predecessors. The stadium was influenced by the French Enlightenment, which was reflected in its reforms.

He wanted to bring the electorate on a par with the secular states of the empire. To this end, he focused primarily on the economy, which had suffered greatly from the French military operations in the Rhineland from 1740 to 1748. To stimulate trade, he founded the Mainz trading stand in 1746, took care of the expansion of the main roads, the construction of new department stores, the establishment of a permanent wine market and two annual trade fairs as well as the improvement of monetary transactions. The trading center began to move again from Frankfurt to Mainz.

The church was not spared from reforms either. In 1746, a redemption law was passed that was supposed to prevent secular property from passing into church hands. In addition, the return of church property into secular hands was promoted.

Further political measures during the reign of Johann Friedrich and his chancellor were the improvement of elementary school education and the social system as well as the creation of a uniform Kurmainzischen land law (1756).

Emmerich Josef Freiherr von Breidbach zu Bürresheim (1763–1774)

Emmerich Josef von Breidbach-Bürresheim was the most important Elector of Mainz in the 18th century. Under his rule, the principles of the Enlightenment were consistently set in all areas. While he only continued the mercantilist policy of his predecessor in the economy , there were no fundamental economic reforms, he concentrated all the more on reforming the education system. He strove primarily to reduce clerical influence, especially the Jesuits , who ruled universities and high schools. This only succeeded with the total dissolution of the Jesuit order by Pope Clement XIV in 1773.

In order to provide the grammar schools and universities with a financial basis, Emmerich Josef ordered the abolition of monasteries, confiscation of their property and the restriction of all privileges. This led to a dispute with the cathedral chapter in 1771, which for its part feared the loss of property and privileges, but ultimately had to bow to the elector. These measures served to improve teacher training and the establishment of new subjects, especially science and practical, so that children could no longer be brought up to be honest Christians but also useful citizens, with the latter being the focus.

Together with the other two Rhenish archbishops, Emmerich Josef tried between 1768 and 1770 to reduce the influence of the Pope on the affairs of his archbishopric. This attempt failed, however, because of the disagreement between the archbishops, the lack of support from the emperor and the unwillingness of the pope to make concessions.

Overall, under Emmerich Josef's government, as under his predecessor, a secularization of electoral politics was observed, as well as a sharper separation between archbishopric and his sovereign function.

On the part of the subjects, who were still traditionally associated with the Church, but also on the part of the chapter, which saw itself diminished in its position, the reforms had to be viewed as an anti-clerical approach and a threat to the Catholic religion. That is why the chapter began to reverse the reforms in the time after Emmerich Josef's death until the election of the new elector.

Friedrich Karl Joseph von Erthal (1774–1802)

Friedrich Karl Joseph von Erthal had previously been the leader of the Conservatives and was elected by the Chapter with the intention of continuing the reactionary course that had just begun. No sooner did Friedrich Karl become elector than he returned to the enlightened absolutism of his predecessors. He carried out reforms in the school system, reorganized the universities by introducing new subjects, and secularized monastic property to finance it, in order to attract an efficient civil service as well as useful citizens. Protestants and Jews were now also admitted to study.

The Chapter's protest was not as energetic as it used to be, as younger people who were familiar with the principles of the Enlightenment were now represented there. Further reforms from the time of Karl Friedrich were the church reform, that is, the abolition of traditional ceremonies, restriction of pilgrimages, introduction of the German language in certain masses, an improvement in the training of priests, orders to abolish serfdom and improvement of agriculture as well as social measures.

The state tried to finally penetrate into all areas of society and take the initiative there. Apart from the resistance of the chapter and the people, for whom the reforms went too far, the bureaucratic system was also overwhelmed. There were difficulties in putting the reforms into practice, some of which failed because the administration was unable to implement the regulations.

The end of the Electorate and Archdiocese of Mainz

In 1790 there was the so-called Mainz knot uprising in Mainz , in which craftsmen provoked by students attacked university organs and demanded the restoration of the old guild freedoms, as well as the influx of numerous French emigrants as a result of the revolution of 1789. After the beginning of the First Coalition War (1792–1797) the elector and cathedral chapter fled to Aschaffenburg in 1792; the city of Mainz was occupied by France . After the interlude of the Mainz Republic (1793), the entire Left Bank of the Rhine was occupied in 1794. According to an “additional convention” agreed in the Peace of Campo Formio (1797), the areas on the left bank of the Rhine were to be ceded to France in a later agreement . The incorporation took place in 1798, the binding assignment not until 1801 in the Peace of Lunéville .

On the right bank of the Rhine , Karl Theodor von Dalberg, elected coadjutor in 1787, took over the government from 1802 to 1803 after Friedrich Karl had resigned. The cathedral chapter still existed, but no longer had any political influence. The bishopric of Mainz on the left bank of the Rhine, newly established as a result of the Concordat of 1801, was handed over to Bishop Joseph Ludwig Colmar .

Secular rule over the territories of Kurmainz on the right bank of the Rhine ended with the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss in 1803. The title of Prince (Arch) Bishop and the secular dignities associated with it (such as prince's hat and coat ) were given in 1951 by Pope Pius XII. abolished.

Kurmainz as namesake

The Bundeswehr barracks in Mainz and Tauberbischofsheim were named after Kurmainz.

There is also a Kurmainz reservist comrade in Mainz. This belongs to the Association of Reservists of the German Armed Forces eV.

See also

- List of the bishops and archbishops of Mainz

- List of the Electorate of Mainz envoys to the Holy Roman Empire

literature

- Elard Biskamp: The Mainz Cathedral Chapter until the end of the 13th century. Diss. Phil. Marburg 1909.

- TCW Blanning : Reform and Revolution in Mainz 1743–1803. Cambridge 1974, ISBN 0-521-20418-6 .

- Anton Philipp Brück (ed.): Kurmainzer school history. Wiesbaden 1960.

- Wilhelm Diepenbach, Carl Stenz (Ed.): The Mainz electors. Mainz 1935.

- Irmtraud Liebeherr: The Mainz cathedral chapter as the electoral body of the archbishop. In: A. Brück (Ed.): Willigis and his cathedral. Festschrift for the millennium celebration of the Mainz Cathedral. Mainz 1975, pp. 359-391.

- Irmtraud Liebeherr: The possession of the Mainz cathedral chapter in the late Middle Ages. Mainz 1971.

- Peter Claus Hartmann: The Elector of Mainz as Imperial Chancellor. Functions, Activities, Claims and Significance of the Second Man in the Old Kingdom. Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-515-06919-4 .

- Michael Hollmann: The Mainz Cathedral Chapter in the late Middle Ages (1306–1476). Mainz 1990.

- Alexander Jendorff: Relatives, partners and servants. Manorial functionaries in the ore monastery of Mainz 1514 to 1647. Marburg 2003, ISBN 3-921254-91-4 .

- Friedhelm Jürgensmeier: The diocese of Mainz, from Roman times to the Second Vatican Council. Frankfurt am Main 1989.

- Friedhelm Jürgensmeier u. a .: Church on the way. The diocese of Mainz. Issues 1–5. Strasbourg 1991-1995.

- Friedhelm Jürgensmeier (Ed.): Handbook of the Mainz Church History. Vol. 1 / 1–2: Christian antiquity and the Middle Ages. Würzburg, 2000. Vol. 2: Günter Christ and Georg May: Archbishopric and Archbishopric Mainz. Territorial and ecclesiastical structures. Würzburg 1997; Vol. 3 / 1–2: Modern times and modernity. Wurzburg 2002.

- Günter Rauch: The Mainz Cathedral Chapter in Modern Times. In: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History . Canonical Department LXI, Vol. 92, Weimar 1975, pp. 161-227; Vol. 93, Weimar, pp. 194-278; Vol. 94, Weimar 1977, pp. 132-179.

- Helmut Schmahl: Internal Deficiency and External Hope for Food: Aspects of Emigration from Kurmainz in the 18th Century. In: Peter Claus Hartmann (Hrsg.): Reichskirche - Mainz Kurstaat - Reichserzkanzler. Frankfurt am Main u. a. 2001 (Mainzer Studies on Modern History, Vol. 6), pp. 121–143.

- Manfred Stimming: The emergence of the secular territory of the Archdiocese of Mainz. Darmstadt 1915.

- Manfred Stimming: The electoral capitulations of the Archbishops and Electors of Mainz 1233–1788. Goettingen 1909.

- Thorough deduction and instruction, that the Hohe Ertz-Stifft Mayntz in seizing the possession of the Frey court to the Hanauischen share Sr. Fürstl. It occurred to Herr Land-Graffen Wilhelm zu Hessen-Cassel, consequently in apprehensa anteriori possessione, there was more to manuteniren than such ... And thus ex plurimis capitibus is impassively colored and invested: To the end, so that the sub- & Obreptio des on the side of your Prince. Passed through by Mr. Land-Graffen Wilhelm zu Hessen-Cassel Against Ihro Churfürstl. Grace to Mayntz and Dero succeeded government Am Höchst-preißl. Kayserl. Cammer dish ... fall in the eyes at first sight; with additional layers ... Häffner, Mayntz 1737. ( digitized version )

- Horst Heinrich Gebhard: Witch trials in the Electorate of Mainz in the 17th century. Publications of the history and art association Aschaffenburg e. V., Volume 31, Aschaffenburg, 1989, ISBN 978-3-8796-5049-1 .

- Erika Haindl: Wizards and witch madness, Against the forgetting of the victims of the witch trials in the Electoral Mainz Office Hofheim in the 16th and 17th centuries. Hofheim a. T., 2001, p. 30.

- Friedhelm Jürgensmeier : The diocese of Mainz, from Roman times to the Second Vatican Council. Frankfurt am Main, 1989, p. 210.

- Herbert Pohl: Witch-faith and fear of witches in the Electorate of Mainz: a contribution to the witch question in the 16th and early 17th centuries. 2nd edition, Stuttgart 1998.

Web links

- Historical maps of the Electorate of Mainz in 1789

- Roman Fischer, Mainzer Oberstift , In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns , September 2, 2010

- Regest of the Archbishops of Mainz

Individual evidence

- ↑ Michael Müller: The development of the Kurrheinischen district in its connection with the Upper Rhine district in the 18th century. Peter Lang international publishing house of the sciences, Frankfurt am Main 2008, p. 66.

- ^ Günter Christ, Erzstift und Territorium Mainz , in: Friedhelm Jürgensmeier (ed.): Handbuch der Mainz Kirchengeschichte , Vol. 2, p. 19.

- ↑ Christ, Erzstift und Territorium Mainz , pp. 19-20.

- ↑ a b Christ, Erzstift und Territorium Mainz , p. 20.

- ↑ Christ, Erzstift und Territorium Mainz , p. 21.

- ↑ Christ, Erzstift und Territorium Mainz , p. 22.

- ↑ Christ, Erzstift und Territorium Mainz , p. 23.

- ↑ Christ, Erzstift und Territorium Mainz , pp. 23–24.

- ↑ a b Christ, Erzstift und Territorium Mainz , p. 24.

- ↑ Christ, Erzstift und Territorium Mainz , p. 25.

- ↑ a b Christ, Erzstift und Territorium Mainz , p. 26.

- ↑ a b c Christ, Erzstift und Territorium Mainz , p. 27.

- ↑ Christ, Erzstift und Territorium Mainz , p. 28.

- ↑ Christ, Erzstift und Territorium Mainz , pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Christ, Erzstift und Territorium Mainz , p. 29.

- ↑ a b Christ, Erzstift und Territorium Mainz, p. 30.

- ↑ Traudl Kleefeld: Against forgetting. Witch persecution in Franconia - places of remembrance. J. H. Röll, Dettelbach 2016. p. 40.

- ↑ The city forgets its victims in FAZ of January 9, 2015, p. 39

- ^ Franz Gall : Austrian heraldry. Handbook of coat of arms science. 2nd edition Böhlau Verlag, Vienna 1992, p. 219, ISBN 3-205-05352-4 .

- ^ Kurmainz reservist comradeship