Eurasian lynx

| Eurasian lynx | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Eurasian lynx ( Lynx lynx ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Lynx lynx | ||||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) |

The Eurasian lynx or northern lynx ( Lynx lynx ) is a species of lynx that is common in Eurasia . In German usage, "lynx" almost always means this species. After the brown bear , wolf and Persian leopard , this cat is the largest land predator in Europe.

The Eurasian lynx has been persecuted for centuries, and systematic attempts at extermination began in Europe in the late Middle Ages . After the species had largely disappeared from Western and Central Europe at the beginning of the 20th century, it immigrated again from adjacent settlement areas from around 1950 and was also reintroduced in a targeted manner . Today the Alps , the Jura , the Vosges , the Palatinate Forest , the Harz , the Fichtel Mountains , the Bavarian Forest , the Rothaar Mountains , the Bohemian Forest and the Spessart are populated by lynxes. In Germany, according to the Red List of the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation , the lynx is still endangered (status 2).

features

Body measurements and weight

With a head body length between 80 and 120 centimeters and a shoulder height of 50 to 70 centimeters, the lynx is the largest cat in Europe and the largest of the four lynx species after the Persian leopard found in the Caucasus . The back length without the head and neck corresponds to the shoulder height, so that the body appears square. The front legs are 20 percent shorter than the rear legs. The large paws prevent the lynx from sinking deep into the snow. The footprints of the lynx are of a width of five to seven centimeters for the front paws and four to six centimeters about three times as large for the rear paw like a domestic cat . The stride length is between 40 and 100 centimeters and can be up to 150 centimeters for sprinting lynxes. In contrast to the fox or dog, lynx tracks usually lack claw prints, as the claws are retracted into skin pockets while running.

In Central Europe, male lynxes, known in the hunter's language as "dogs", weigh on average between 20 and 25 kilograms, depending on the region. Particularly light specimens weigh only 14 kilograms and very heavy animals can reach 37 kilograms. Females are on average 15 percent lighter than males. Their weight is usually around 15 to 20 kilograms, with extreme values of twelve and 29 kilograms respectively.

Other features of appearance and sensory performance

The Eurasian lynx is connected to the other species of the genus by the brush ears, the broad and rounded head and the very short tail. The Eurasian lynx is between 15 and 25 centimeters long and ends in a black tip. The Eurasian lynx is characterized by a very pronounced whiskers that it can spread widely. The function of the whiskers is not fully understood. The animals probably express their mood towards other conspecifics through the position of the whiskers. The whiskers may also serve as a reflector for sound sources.

The hairbrushes on the pointed, clearly triangular ears are up to five centimeters long and enhance the ability to locate sound sources. Studies have shown that lynxes can still hear the rustling of a mouse from a distance of 50 meters and can hear a passing deer 500 meters away. The almond-shaped cut and forward-oriented eyes are golden yellow, yellow-brown or ocher-brown. They are the most important sensory organ of the lynx and about six times as sensitive to light as the human eyes, which allows the lynx to hunt during twilight and at night. The sense of smell plays only a subordinate role in hunting.

The full set of teeth on a lynx usually consists of 28 teeth. On both sides of the upper and lower jaw there are three incisors, one strongly developed canine with so-called dagger grooves, two anterior molars or premolars and one molar or molar; sometimes an additional molar is formed on one or both sides in the lower jaw.

The fur of the Eurasian lynx is reddish to yellow-brown on the upper side of the body during the summer and gray to gray-brown during the winter months. The chin, throat, chest, abdomen and the inside of the legs are whitish gray to creamy white. The spotting of the fur varies from person to person, but it can also be almost completely absent. The undercoat of the fur is dense, the guard hairs above are five to seven centimeters long. The winter fur is one of the densest in the animal kingdom. Long legs, thick fur and the low wing loading due to the wide paws enable the lynx to hunt successfully even in snow conditions of up to half a meter. Higher snow conditions hinder him when hunting, so that he then withdraws to less snowy regions.

distribution

Historical circulation area

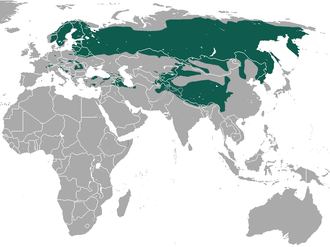

The Eurasian lynx is one of the most common types of cats. At the beginning of modern times, its European distribution area extended from the Pyrenees in a wide belt to the Urals . According to some scientists, however, the lynx was absent in Iceland , the British Isles and the Mediterranean islands, in the coastal hinterland of the North Sea, in Denmark , in the southern Norwegian fjordland and in the far north of Fennoscandinavia and on the entire Kola peninsula .

In Asia, the lynx was widespread over almost all of Siberia from the Urals to the Pacific, as well as in northern China , Tibet , parts of Mongolia and Turkestan . Its distribution limit reaches the Arctic Circle in the north - no other cat species penetrates further north than the Eurasian lynx. In the south, its range extended to Nepal , northern India , northern Pakistan , Persia and possibly even to Palestine .

Before resettlement, the last lynxes were killed in Germany in 1818 in the Harz near Lautenthal , in 1846 in the Swabian Alb near the ruins of Reußenstein , also in 1846 near Zwiesel in the Bavarian Forest and around 1850 in the Bavarian Alps. The Eurasian lynx was last seen in the French Alps before it was reintroduced in 1903, and in Switzerland in 1904 at the Simplon Pass . The lynx was able to keep for a relatively long time in some parts of Austria. The last autochthonous Austrian lynx was shot in 1918 in the Balderschwanger valley in the Bregenzerwald .

Between 1918 and around 1960, the Eurasian lynx was largely extinct in Western Europe. However, the species survived in large parts of northern, eastern and south-eastern Europe as well as in most of the Asian occurrence areas, with the westernmost occurrences around 1960 in southern Sweden , eastern Poland and eastern Slovakia .

Resettlement measures and current distribution area in Europe

Due to numerous reintroductions, some areas of Western Europe such as the Alps , the Jura , the Vosges , the Harz Mountains and the Bohemian Forest have been repopulated. In the northwestern Alps, almost all suitable habitats are now occupied by lynxes. These repopulation programs have been controversial in parts of the public and their implementation has not always proven to be problem-free. The specific problems are dealt with in the chapter on man and the lynx .

Switzerland was the leader in the reintroduction of the lynx: on April 23, 1971, the first two lynx from the Carpathian Mountains were released in Switzerland in the area of the Huetstock hunting district near Engelberg near Lucerne . By 1976, more lynxes were reintroduced, which by 1979 had already spread over an area of 4,500 square kilometers. In 1991 lynx were again populated in the Swiss north-west and central Alps and 5,000 square kilometers in the Jura. In the cantons of St. Gallen, Zurich, Thurgau and both Appenzell in north-eastern Switzerland, a total of nine more lynxes were released between 2001 and 2003, which should also establish a sustainable population there.

In 1976, nine lynxes from Slovakia were released into the wild in the border triangle Styria-Carinthia-Salzburg in Austria, but the resulting population has remained small to this day. In the French Vosges, where 19 lynxes were released into the wild in 1983, a population developed that is on the verge of extinction. The offspring of three pairs of lynx released in Slovenia now inhabit a distribution area from the Slovenian border with Italy and Austria to Bosnia-Herzegovina .

In Germany, individual lynxes probably immigrated to the Bavarian Forest from the Czech Republic as early as the 1950s . In 1962 there was the first reliable evidence of lynx in the Elbe Sandstone Mountains, and in 1969 lynx were observed again for the first time in the Dübener Heide north of Leipzig . In the meantime, in addition to the population in the Bavarian Forest, there are again lynx in Saxon Switzerland , in the Palatinate Forest , in the Fichtel Mountains and in the Spessart . In the Harz National Park a running reintroduction project , under which since 2000 a total of 24 lynx were released; 2002 saw the first birth of wild lynxes since the reintroduction. As part of the lynx monitoring project , a fairly stable population was detected in 2011, especially in the densely wooded districts of Northern Hesse, and offspring were also observed with photo traps. This population is probably descendants of the Harz animals.

Individual lynxes , probably immigrating from Switzerland , have also been spotted in the Black Forest . Since 2004, lynxes have been observed in various parts of Germany, the origin of which is often unclear, for example in the upper Danube Valley , in the Eifel , in the Teutoburg Forest , in the Odenwald or in Altengrabow . In a storm night from January 18 to 19, 2007 ( Hurricane Kyrill ), a pair of lynxes managed to escape from the Suhl zoo into the Thuringian Forest . However, former enclosure animals only have a chance of survival if they have the ability to beat prey in the wild.

Individual sightings are not yet evidence that lynxes have repopulated a region and reproduce there. As a rule, lynxes only establish territories if these areas have territorial connections to neighboring lynx territories.

In February 2018 there were 77 lynxes in Germany; In the monitoring year 2016/17 the birth of 37 young animals was recorded. (A monitoring year, also known as a lynx year, is adapted to the life cycle of the lynx; it begins on May 1 with the approximate date of birth of the young and ends on April 30 of the following year.) A slight increase in the population of seven lynx compared to the previous year is based on reintroductions in the Palatinate Forest. The Federal Agency for Nature Conservation registered four lynxes found dead in the monitoring year 2016/17 (compared to 22 in the previous monitoring year), but assumes a higher number of unreported cases. The main causes of death in Germany are road accidents, illnesses and illegal killings.

In Great Britain there is a debate as to whether the lynx, which most scientists believe was to be found there until around 500 to 700 AD and was exterminated by human pursuit, should be reintroduced. It is also up for discussion whether the Iberian lynx , which is acutely threatened with extinction , should be introduced instead of the Eurasian lynx, which is not considered endangered in its entirety .

Habitat and territorial requirements

The Eurasian lynx generally prefers large forest areas with dense undergrowth as a habitat and only uses open landscapes and human settlements on the edge and temporarily. Forests with a very small-scale structure with old wood islands, clearings, rocky slopes and swampy zones offer ideal conditions for hunting. Eurasian lynx can also be found in the rocky mountain zone up to a height of 2500 meters, in fens and on heathland, as well as in the predominantly treeless high plains of Central Asia . These habitats offer a large number of cover options between rocks and bushes. In the mountains of the former Soviet Union, the lynx migrate to lower altitudes in winter. Lynxes are rare in regions with high wolf densities and an increase in the lynx population has been reported in several regions after the wolf population there decreased. Telemetric surveys, which have accompanied a number of reintroduction projects over the past decades, have shown that lynxes hunt a large part of their prey on the edge of forests and rarely enter agricultural areas. During the day, lynx stay in their hiding place and tolerate being close to humans. Both in the Vosges and in the Bavarian Forest, female lynxes raised young not far from places that are heavily frequented by tourists.

The territory sizes of the Eurasian lynx vary greatly, mainly due to the food supply of prey, but also depending on the forest density and structure, the coverage possibilities, the settlement by humans and the topographical conditions. Investigations in the Swiss Northern Alps revealed an average area size of 250 square kilometers, with the smallest area comprising 96 and the largest 450 square kilometers. In the Jura, where the proportion of forest is higher, an action area of 100 to 150 square kilometers was determined. According to KORA, the size of average residential areas is 90 km² for females and 150 km² for males. In the Carpathian Mountains , western Russia and the former Yugoslavia , however, a population density of one lynx per 10 to 40 square kilometers was determined. Females generally have smaller territories than males, whose territory is usually twice as large and can overlap with the territories of up to two females. Territory boundaries are marked by urine , solution and sometimes also by scratch marks.

Studies on the spatial behavior of lynxes within their territory are mainly from the Polish Białowieża National Park . There, lynx roamed around 1.7 to 2.6 percent of their territory in one day. The use of space and the size of the area are due to the way the lynx hunted. As a surprise hunter, he mainly hits prey that behave carelessly. During a longer stay in a part of his territory, his prey adjust to the presence of the predator and behave shyly. In order to ensure adequate hunting success, the lynx is therefore dependent on repeatedly changing its hunting area within its territory.

Way of life

Loot spectrum

Deer and chamois often make up more than 80 percent of the prey spectrum. Other animal species, on the other hand, are underrepresented in relation to their occurrence. The range of prey also includes practically all small and medium-sized mammals and birds present in the respective habitat. As well as other red fox , raccoon , rabbit , young wild boar , squirrels , mice, rats and marmots to the beat of lynx prey, including fish be consumed. Small and medium-sized ungulates with a weight of 20 to 25 kilograms are the preferred prey. Over large parts of Eurasia, the deer is the preferred prey of the lynx and the roe deer's range largely coincides with that of the lynx. In Finland, where deer are naturally absent, and in Sweden and Norway, where deer were only introduced after 1900, lynxes are very common in beating young reindeer .

In the Alps, deer and chamois dominate the prey spectrum . In addition to deer, red deer calves and brown hares also play an important role in the Bavarian Forest . Of the 102 lynx prey found there, there were 71 roe deer, 17 red deer, eight hares, three wild boars and three foxes. In the case of wild boars, it is mostly young animals that fall victim to it. Adult wild boars are too defensive to be considered as prey for the lynx. In the Swiss Jura, which is rich in foxes, foxes make up more than ten percent of the lynx prey spectrum. In the taiga, on the other hand, the lynx mainly hunts mountain hares and grouse . Adult male lynx also prey on wolf pups . Aufgefundenes carrion eating lynx only in times of emergency, but they return to hunted prey back (see below).

Hunting behavior

The lynx lives as a solitary animal that hunts primarily at dusk and at night. As a rule, lynxes rest in their hiding places during the day. Active lynx can also be observed during the day during the ranting season . They also hunt during the day when they raise young animals or when prey is rare. During the hunt, they cover an average of ten kilometers.

The Eurasian lynx is a surprise or ambulance hunter who hits its prey primarily on regularly passed deer passes. The hunt takes place according to the type of cat by ambushing or sneaking up with a final jump, or a short spurt of usually less than 20 meters in length. In these short sprints, the lynx can reach a speed of almost 70 km / h. The hind legs, the length of which exceeds that of the front legs, favor a quick sprint towards the prey. The prey is suffocated by a bite in the throat. If the prey escapes the lynx in such an attack, the prey is at best pursued over a short distance. The lynx sometimes hides the undone prey under branches and leaves. As a rule, lynxes return to their cracks several times. They consume between 1 and 2.7 kilograms of meat per night. The daily food requirement of pure meat for a 25 kg Eurasian lynx is around 1.1 kg.

Mating and rearing the young

The couples only get together during the mating season between February and April. Females usually the first time participate in her second winter at the Ranz . Males usually do not look for a female ready to cover until their third winter. The otherwise solitary animals mark the core area of their territories with their strong smelling urine during this time. The markings are preferably placed at the lynx's nose level on rhizomes or stones. The loud rant calls, which resemble a drawn out "Ouh", can also be heard frequently during this time.

Once a male has found a lynx that is ready to mate, it spends several days in their vicinity. If several males meet, they fight for the right to mate. During copulation, the male approaches the female from behind and then jumps up. Mating, during which the male bites into the cat's neck fur, takes about three minutes; Numerous copulations take place every day. Basically, the lynx mates with only one male during the sack season .

The two to five cubs are usually born in a sheltered place after a gestation period of around 73 days, for example in a rock cave or under a root plate. The sex ratio of the young is balanced at birth. The young, which are already hairy, weigh about 240 to 300 grams at the time of their birth and are blind during the first 16 to 17 days of life. You are only looked after by the mother. From the age of four weeks, they gradually begin to feed on the mother's prey. They are suckled up to a maximum of five months of age. Young animals stay with their mother until next spring. Then they try to find their own territory. Young female lynxes reach sexual maturity at the age of 21 months. The male cats, on the other hand, are normally only able to reproduce after they have reached the age of 33 months.

The mortality of the young animals is very high. While adult lynx are hardly endangered by other predators, juveniles are struck by brown bears, wolves, wolverines and occasionally even foxes. In Asia, the leopard is also a potential predator for young lynx. The high mortality of the young animals is, however, less caused by predators than by traffic accidents and to a lesser extent by diseases. As far as we know today, lynxes are susceptible to all bacterial and viral diseases that also occur in domestic cats. Furthermore, young animals only have a chance of survival if they find an unoccupied territory after separating from their mother. Only about every fourth young lynx succeeds in this.

The life expectancy of lynxes that succeed in establishing a territory is ten to 15 years. Animals kept in captivity can live up to 25 years.

Endangerment and existence

The species as a whole is classified as "not endangered" according to the IUCN . However, in most countries as well as in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, the hunt for lynx is either prohibited or strictly regulated. International protection is provided by the Bern Convention , the Bonn Convention , the Fauna-Flora-Habitat Directive of the European Union (Annexes II and IV) and CITES . In Germany, the lynx is a species that is “strictly protected” by the Federal Nature Conservation Act; the illegal killing of a lynx can be punished as a criminal offense with up to five years imprisonment. The biggest problem for the lynx in Central Europe is poaching , which has led to a dramatic decline in the lynx population in the Balkans. From the Balkan lynx (subspecies Lynx lynx balcanicus ) there is only from 20 to 40 adult individuals; they live in Albania and North Macedonia .

The total population in Europe is estimated at around 7,000 lynx, while there are a little less than 50,000 animals worldwide. The success of the reintroduction in Central and Western Europe is not certain, as it remains to be seen whether the established populations will be able to survive in the long term.

Holdings of European countries

The largest stocks of Lynx lynx are in Russia . Other populations of Lynx lynx in Europe are located in:

- Albania : maximum 20

- Bosnia and Herzegovina : 60-1200

- Bulgaria : 700

- Germany : 85

- Estonia : 1000

- Finland : 2700-2900

- France : maximum 100

- Croatia : 40-60

- Latvia : 600

- Lithuania : 80-100

- North Macedonia : maximum 50

- Norway : 600

- Austria : 15-20

- Poland : 180

- Romania (especially in the Carpathian Mountains ): 1500

- Sweden : 1000-1400

- Switzerland : 205

- Slovakia : (especially in the Carpathian Mountains): 450

- Slovenia

- Czech Republic : maximum 50

- Ukraine : 350-400

- Belarus : 400-450

Man and lynx

The image of the lynx

Lynx play a much smaller role in European myths and fairy tales than wolf and bear. This can be seen as evidence that humans had far less contact with the not particularly shy but barely visible lynx than with the two other large European predators . The concise dictionary of German superstitions published in 1933 also states that the lynx is hardly mentioned any more. Since ancient times the lynx has been considered to be extremely sharp-sighted (see Accademia dei Lincei ), in Germany also as clairaudient ("ears like a lynx") and stealthy ("stealing something from someone").

In folk medicine , lynx claws set in precious metals and worn as an amulet were used as protection against nightmares and epilepsy . Other parts of the body of the lynx were also used: lynx fat should help against gout , and in the case of swollen tonsils it should be helpful to drink through the right hollow thighbone of the lynx.

Compared to the wolf, the lynx has a less negative connotation: large parts of the population are positive or indifferent to the return of the lynx. The return of the wolf, on the other hand, is accompanied by a much more negative attitude and is more strongly associated with endangering people and pets. In the opinion of the nature conservation expert Josef Reichholf , this is due to the fact that cat species are not suitable in a comparable way to build up an enemy image. This simplifies resettlement projects, as opposition to these projects is mainly limited to stakeholders such as farmers and hunters who fear effects on game and grazing animals. Josef Reichholf sees the early extermination of the lynx in Central and Western Europe primarily because the lynx were easier to hunt and with less effort than the wolf.

Resettlement problems

The last few decades have shown that it is difficult for lynxes to colonize new habitats. When establishing territory, which precedes reproduction, a lynx seeks territorial connection to the territory of other lynxes. A natural settlement of former habitats therefore requires a very long period of time and presupposes that there is high population pressure in the already existing habitats. A return of the lynx to its old range can therefore usually only be achieved with human help.

The reintroduction of the lynx by humans has been accompanied by a series of resistance and criticism. The most common concerns raised prior to resettlement relate to damage to domestic animals and game. In 2007 there was a sharp decline in the lynx population in the Bernese Oberland . Chopped off lynx paws, cut-off transmitter collars and the laying of poisonous bait sent to the hunting inspection of the canton of Bern show that this decline was the work of criminals. In Switzerland, the illegal killing of lynxes constitutes poaching . In 2012 and 2013, two lynxes were poisoned or shot in the Bavarian Forest. In May 2015, four forepaws of lynx were found in the area of the Lamer Winkel ( district of Cham ), which had been placed near a photo trap of a lynx research project. In Austria, in January 2017, a hunter who shot down a male lynx from a resettlement program in the Kalkalpen National Park was sentenced by the Supreme Court in the last instance to pay a good 12,000 euros to the National Park; Criminal proceedings were also ongoing against her husband, also for the illegal killing of a lynx.

Capturing of farm animals

In Switzerland, around 1000 domestic sheep fell victim to the lynx in the first three decades after the lynx was reintroduced . Newborn calves were only torn in exceptional cases. Experience has shown that individual lynxes specialize in hunting farm animals such as goats and sheep. Above all animals that remain far away from human settlements at night and whose pastures are near the edge of the forest are torn. Similar to other predators such as red fox or martens, attacks on pets can lead to so-called surplus killing : far more animals are killed or injured than the predator needs for food. Wild animals such as fallow deer or European mouflons kept in large gates are also endangered by the lynx .

As a rule, attacks on grazing animals, which are often largely left to their own devices on the alpine pastures, are rare. As ambulance hunters, lynxes are more likely to hunt deer and chamois than attack domestic animals. Similar to other resettlement projects, for example for bearded vultures , wolves and brown bears , intensive cooperation with the local population and awareness-raising campaigns have contributed to the success of resettlement projects. This also includes compensation for farmers who lose pets to lynxes, which is as inexpensive and hassle-free as possible. Wherever herd guard dogs were established due to the simultaneous settlement of wolves or brown bears or house donkeys were added as herd donkeys to the flocks of sheep and goats, these measures have proven to be an efficient precaution against attacks by lynxes.

In Switzerland, preventive measures against lynx cracks are subsidized with up to 100 percent of the costs. In the case of pastures that have proven to be particularly endangered due to their proximity to the forest, depending on the situation, even the rent is paid in order to stop further grazing by sheep or goats. In Switzerland, however, clear criteria also regulate when a lynx is to be classified as so problematic that a shooting permit is granted.

Impact on other animal species

Lynx do not have a negative impact on the population of huntable cloven-hoofed animals . The numbers of deer and chamois hunted by lynxes are usually significantly lower than those of fallen game (animals that have killed diseases and accidents) and are significantly lower than those shot by hunters in the same area. However, the presence of the lynx does not contribute to an improvement in the health of the livestock as expected. Due to the hunting technique used by lynxes, it is not just sick and overaged animals that fall victim to them.

A common argument against the settlement of lynx was the potential threat to grouse populations . In 1975, for example, the hunting authorities of Lower Saxony rejected the application of the Göttingen Institute for Wildlife Biology to settle lynxes in the Harz Mountains because they saw the capercaillie reintroduction to the wild in this way . In fact, grouse represent a certain proportion of the lynx's diet in the Carpathians and Scandinavia, among others. The main prey of the lynx is generally those species of its prey spectrum that are frequently represented in its territory. Studies in Switzerland have shown that even in areas with good black grouse and capercaillie populations, lynxes only beat these bird species in exceptional cases and clearly prefer the numerous deer and chamois there.

, Greatly (see the article The browsing damage in forests, caused by a high Paarhuferbestand a negative impact on the natural forest regeneration from Red Deer chapter damage ). There is often a concentration of damage caused by browsing because red deer stand close together. The presence of lynx has a positive effect here, as it breaks up such collections over the long term, so that the animals spread over larger areas.

Successes and failures of the resettlement programs

The reintroduction of the lynx has not been free from setbacks. Illegal releases that took place in Switzerland and the Bavarian Forest in the 1970s have permanently damaged the credibility of resettlement programs in these regions. In addition, it has been shown that only carefully selected lynxes are able to establish themselves in the wild. Most of the successful resettlements were those caught in the wild with hunting experience . Captive lynx are mostly unable to capture enough prey. There have also been a number of illegal killings and poisoning campaigns in repopulated areas.

The population of the lynx in German low mountain ranges is currently still too small and the stocks are partially isolated. Walking corridors are necessary so that stocks such as those in the Harz Mountains do not become islands. Sufficient genetic variability is only ensured from a population of 50 to 100 animals that can reproduce with one another. The same applies to Switzerland, which has so far had the greatest success in resettlement. The two established lynx populations are limited to the Jura Mountains and the Northern and Central Alps. The mid-plateau, on the other hand, is unpopulated and there is no genetic exchange between the two populations.

Systematics

Systematic classification

For a long time it was debated whether lynxes are only a subgenus of the genus Felis . That is why the Eurasian lynx is sometimes found in older literature under the name Felis lynx . Today, the classification of the lynx in the independent genus Lynx is accepted and the Eurasian lynx is accordingly listed as Lynx lynx .

Despite their size, the lynx belong to the small cats and form the sister group of a clade to which the pumas ( Puma ), the cheetah ( Acinonyx jubatus ), the manul ( Otocolobus manul ), the old cats ( Prionailurus ) and the real cats ( Felis) ) belong.

The Eurasian lynx is now regarded as an independent species within the lynx genus. It used to be combined with the Canadian lynx and the Iberian lynx to form a common species. However, based on fossil findings, it is known that the line of development of the Iberian Iberian lynx split off in southwestern Europe in the Villa Franchian , the beginning of the Pleistocene . Compared to the Iberian lynx, the fossil record of the Eurasian lynx is much less coherent. What is certain, however, is that this developed in the East Palearctic and spread from there in both western and eastern directions. The bobcat and Canadian lynx apparently descended from ancestors of the Eurasian lynx who came to Alaska in two waves of immigration over the Bering Bridge : the first of these waves of immigration gave rise to the bobcat 2.6 million years ago, and the second 200,000 years ago the Canadian lynx .

Subspecies

The number of subspecies of the lynx and their geographical delimitation are controversial. Depending on the source, between four and 14 subspecies are named. Sunquist & Sunquist (2009) differentiate between the following subspecies:

- Amur lynx ( L. l. Neglectus ): Lower Amur region in the far east of Russia and northern China, Manchuria , Korea

- Baikalluchs ( L. l. Kozlovi ): Central Siberia between Yenisei and Lake Baikal

- European lynx ( Lynx lynx lynx ): nominate form ; Distribution from Western Europe and Scandinavia over the European part of Russia to Siberia, where the subspecies reaches the Yenisei in the east

- Sardinian lynx † ( Lynx lynx sardiniae ); However, this is the Sardinian black cat ( Felis lybica lybica ), which was misidentified

- Carpathian lynx ( L. l. Carpathica ): Carpathian Mountains in Romania, Slovakia, Poland and the Czech Republic as well as the Balkan Peninsula

- Caucasian lynx ( L. l. Dinniki ): Caucasus , Asia Minor , Northern Iran , Northern Iraq

- Siberian lynx ( L. l. Wrangeli ): Eastern Siberia, Northeast China

- Central Asian lynx ( L. l. Isabellinus ): This subspecies has a light sand-gray to isabel-colored fur. Inhabits Central Asia, Altai Mountains , Tibet , Nepal , North India , North Pakistan , Tajikistan , Kyrgyzstan , Uzbekistan , Turkmenistan , Kazakhstan and Northwest China ; Synonymous with Altailuchs ( L. l. Wardi )

The IUCN's Cat Specialist Group only recognizes six subspecies in its 2017 revision of the cat system.

- European lynx ( Lynx lynx lynx )

- Balkan lynx ( L. l. Balcanicus ), possibly a synonym of L. l. dinniki

- Carpathian lynx ( L. l. Carpathicus )

- Caucasian lynx ( L. l. Dinniki )

- Central Asian lynx ( L. l. Isabellinus )

- Siberian lynx ( L. l. Wrangeli ), including L. l. kozlovi et al. L. l. neglectus

literature

- Antal Festetics (ed.): The lynx in Europe. Contributions from the 1st International Lynx Colloquium in Murau / Styria, 7. – 9. May 1978. Kilda, Greven 1980, ISBN 3-921427-43-6 ( Topics of the time. Issue 3).

- Breitenmoser Urs, Christine Breitenmoser sausages: The lynx. A large carnivore in the cultural landscape. Salm, Wohlen 2008, ISBN 978-3-7262-1414-2 (two volumes).

- H. Hemmer: "Felis (Lynx) lynx" Linnaeus, 1758. Luchs, Nordluchs. In: M. Stubbe, F. Krapp (ed.): Raubsäuger – Carnivora (Fissipedia), part 2. Mustelidae 2, Viverridae, Herpestidae, Felidae. Aula, Wiebelsheim 1993, ISBN 3-89104-528-X ( Handbook of Mammals in Europe. Volume 5), pp. 1119–1167.

- Marco Heurich and Karl Friedrich Sinner: The lynx. The return of the brush ears, book and art publisher Oberpfalz, 2012, ISBN 978-3-935719-66-7 .

- Jürgen Heup: Bear, lynx, wolf. The silent return of the wild animals , Franckh-Kosmos, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-440-11003-4 .

- Robert Hofrichter, Elke Berger: The lynx. Return on quiet paws. Stocker, Graz 2004, ISBN 3-7020-1041-6 .

- Robert Hofrichter: The return of the wild animals. Stocker, Graz 2005, ISBN 3-7020-1059-9 .

- Roland Kalb: bear, lynx, wolf. Persecuted, exterminated, returned , Leopold Stocker Verlag, Graz 2007, ISBN 978-3-7020-1146-8 .

- RM Nowak: Walker's Mammals of the World, Volume 1. 6th edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1999, ISBN 0-8018-5789-9 , p. 806.

- Mel Sunquist and Fiona Sunquist: Wild Cats of the World . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2002, ISBN 0-226-77999-8 .

- Manfred Wölfl, Heinz Klein: Luchswege. Mittelbayerischer Verlag, Regensburg 2000, ISBN 3-931904-84-9 .

- Manfred Wölfl (Red.): Lynx management in Central Europe. Summary of the lectures and discussions at the conference in Zwiesel 10. – 11. November 2003. Government of Niederbayern, Landshut 2004 ( Nature Conservation in Niederbayern. Issue 4).

Web links

- Species profile of the Eurasian lynx; IUCN / SSC Cat Specialist Group (English)

- Lynx lynx in the Red List of Threatened Species of the IUCN 2008. Posted by: K. Nowell u. a., 2008. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- Lynx in the mountain forest ( Memento from February 1, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF file; 352 kB) - Lynx and hoofed game management in the Bavarian Forest National Park

- Lynx hunt in the Spessart ( Memento from September 20, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF file; 247 kB) - About the extermination of the lynx in the 17th century.

- Project Lynx Switzerland (requires JavaScript)

- Lynx research in the Bavarian Forest National Park

- Large Carnivore Initiative for Europe (English)

- Species protection project lynx in Bavaria

- The lynx in Hessen

- The lynx in the Harz region

- The lynx in the Bohemian Forest, North Austria

- The lynx working group in Baden-Württemberg

- SNU project film: Release in the Palatinate Forest Biosphere Reserve 2016

Individual evidence

- ↑ NABU INFO: Lynx in Germany - Successful return of the "brush ears"? Naturschutzbund Deutschland eV Bonn 2006. Retrieved on March 3, 2018.

- ↑ Main network: The lynx in the Spessart .

- ^ BfN: Lynx lynx (Linnaeus, 1758) ( Memento from March 30, 2016 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Wild animal - lynx. In: naturpark-bayer-wald.de. Retrieved December 8, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c d Stubbe and Krapp, p. 1122.

- ^ Hofrichter, 2005, p. 140.

- ↑ Kalb, p. 18 f.

- ↑ a b c Stubbe and Krapp, p. 1123.

- ↑ a b Heup, p. 34.

- ↑ Kalb, p. 19.

- ^ Hofrichter, 2005, p. 144.

- ↑ Tor Kvam: Supernumerary teeth in the European lynx, Lynx lynx lynx, and their evolutionary significance. In: Journal of Zoology . Vol. 206, No. 1, 1985, pp. 17-22, doi: 10.1111 / j.1469-7998.1985.tb05632.x .

- ^ Sunquist, p. 165.

- ↑ Hofrichter, p. 141.

- ↑ a b Stubbe and Krapp, p. 1146.

- ^ Animals Diversity Web: Lynx lynx - Eurasian lynx.Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ^ Kalb, p. 57.

- ↑ Stubbe and Krapp, p. 1134. There you will also find more detailed information about the disputed points of the historical distribution area.

- ↑ a b c Hofrichter and Berger, p. 19.

- ^ Kalb, pp. 60 and 62.

- ↑ KORA .

- ^ Hofrichter and Berger, p. 66.

- ↑ BfN Lynx Monitoring (PDF).

- ↑ NABU Federal Wildlife Trail Plan (PDF) p. 15, Fig. 6.

- ↑ Kalb, p. 33.

- ↑ Erich Aschwanden: How the lynx came back to Switzerland In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung of April 23, 2018

- ↑ a b Kalb, p. 83 ff.

- ^ Hofrichter and Berger, p. 26.

- ↑ Heup, p. 38.

- ^ "Le lynx ne répond plus dans les Vosges" .

- ↑ Hofrichter and Berger, p. 21 f.

- ↑ Kalb, p. 168.

- ↑ Animals and Plants . Spessart Nature Park .

- ↑ Diana Wetzestein: Hessen: Lynx at home again . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , January 19, 2012.

- ↑ 2011 and 2014, Potsdamer Neuste Nachrichten ( Memento from December 18, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (April 24, 2014).

- ↑ a b c Hofrichter and Berger, p. 102.

- ↑ a b Federal Agency for Nature Conservation: Counting of rare brush ears - Where can you find lynx in Germany? June 5, 2019, accessed December 2, 2019.

- ^ Lynx UK trust. Retrieved March 12, 2015 .

- ↑ Chris Thomas: Should the lynx be reintroduced to Britain? March 12, 2015, accessed March 12, 2015 .

- ^ Sunquist, p. 166 and p. 167.

- ↑ a b c Sunquist, p. 167.

- ↑ Kalb, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Kalb, pp. 24-26.

- ↑ KORA: KORA. Retrieved March 17, 2018 .

- ↑ Stubbe and Krapp, p. 151.

- ↑ Hofrichter and Berger, p. 98.

- ^ Hofrichter and Berger, p. 100.

- ^ Hofrichter and Berger, p. 101.

- ↑ Kalb, pp. 37-39.

- ^ Sunquist, p. 168.

- ^ Sunquist, pp. 168-169.

- ↑ Heup, p. 33.

- ↑ Kalb, p. 39.

- ↑ Vadim Sidorovich: Mortality in wolf pups.

- ↑ a b Josef Reichholf: The bear is loose. A critical status report on the chances of our large animals surviving. Herbig, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-7766-2510-3 , pp. 75ff.

- ^ Hofrichter, 2005, p. 139.

- ↑ Kalb, p. 48.

- ↑ a b Stubbe and Krapp, p. 1150.

- ↑ Jens Kuhr: Such a clever lynx. In: Abendblatt.de . Retrieved December 8, 2018 .

- ↑ Stubbe and Krapp, p. 1151.

- ↑ Heup, p. 31 and Hofrichter, 2005, p. 142.

- ^ Hofrichter and Berger, p. 104.

- ^ Hofrichter and Berger, p. 109.

- ↑ Heup, p. 32.

- ↑ BfN: Lynx lynx (Linnaeus, 1758) ( Memento from March 30, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Scientific services of the German Bundestag: Legal requirements for the protection of species of the lynx. File number: WD 7 - 3000 - 053/16; April 12, 2016. Accessed February 21, 2018.

- ↑ Lynx lynx ssp. balcanicus in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015.4. Posted by: D. Melovski, U. Breitenmoser, M. von Arx, C. Breitenmoser-Würsten, T. Lanz, 2015. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- ↑ Heup, p. 39.

- ^ The second Balkan lynx picture in Albania. (PDF; 375 kB) In: Association for the Protection and Preservation of Natural Environment in Albania. April 24, 2012, accessed May 1, 2012 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Distribution of the Eurasian lynx. In: WWF Austria. Retrieved November 30, 2014 (data: 2013).

- ↑ a b c d e f Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) in Europe ( Memento from February 12, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Lynx acceptance in Poland, Lithuania, and Estonia. (PDF) September 22, 2012, accessed on September 22, 2012 (English).

- ↑ Riista- ja kalatalouden tutkimuslaitos: Ilveksen kanta-arviot ( Memento of December 3, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) , as of May 2014.

- ↑ Brojnost i trend populacije risa u Hrvatskoj. In: life-vuk.hr. Retrieved March 20, 2019 (Croatian).

- ↑ Naturvårdsverket: Fakta om lodjur: Tillståndet för lodjursstammen , status of the estimate: February 2013.

- ↑ Lynx - hunter on quiet paws. WWF Switzerland, accessed on March 17, 2018 .

- ^ Hofrichter and Berger, p. 32.

- ^ Hanns Bächtold Stäubli: Handbook of German Superstition , 1933, keyword lynx.

- ↑ Swiss Federal Office for the Environment, press release August 31, 2007.

- ↑ Killed lynx in the Bavarian Forest - Herrmann does not want a Soko lynx at the LKA . In: br.de . May 29, 2015. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ↑ APA report: three months conditionally for shooting a lynx in the Kalkalpen National Park . In: derstandard.at . November 5, 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ↑ Die Presse: Huntress has to pay compensation for shooting lynx. January 10, 2017, accessed September 7, 2018.

- ↑ Heup, p. 37.

- ^ Hofrichter and Berger, pp. 117f and p. 141.

- ↑ Kalb, pp. 39 and 52 and Hofrichter, 2005, p. 135.

- ↑ Kalb, p. 52.

- ↑ Hofrichter and Berger, p. 81.

- ^ Hofrichter and Berger, p. 108.

- ^ Hofrichter and Berger, p. 79.

- ^ William J. Zielinski, Thomas E. Kuceradate: American Marten, Fisher, Lynx, and Wolverine. Survey Methods for Their Detection . Diane, 1998, ISBN 0-7881-3628-3 , pp. 77-78 .

- ↑ a b Carron Meaney; Gary P. Beauvais: Species Assessment for Canada Lynx (Lynx Canadensis) in Wyoming. (PDF) (No longer available online.) United States Department of the Interior , Bureau of Land Management, 2004, archived from the original September 26, 2007 ; Retrieved June 25, 2007 .

- ↑ Stephen J. O'Brien, Warren E. Johnson: The New Pedigree of Cats. In: Spectrum of Science. 6/2008, pp. 54-61.

- ^ Hofrichter and Berger, p. 139.

- ^ ME Sunquist & FC Sunquist (2009): Family Felidae (Cats). (P. 151). In: DE Wilson, RA Mittermeier (ed.): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 1: Carnivores. Lynx Edicions, 2009. ISBN 978-84-96553-49-1 .

- ^ A b AC Kitchener, C. Breitenmoser-Würsten, E. Eizirik, A. Gentry, L. Werdelin, A. Wilting, N. Yamaguchi, AV Abramov, P. Christiansen, C. Driscoll, JW Duckworth, W. Johnson, S.-J. Luo, E. Meijaard, P. O'Donoghue, J. Sanderson, K. Seymour, M. Bruford, C. Groves, M. Hoffmann, K. Nowell, Z. Timmons, S. Tobe: A revised taxonomy of the Felidae . The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN / SSC Cat Specialist Group. In: Cat News. Special Issue 11, 2017, pp. 42–44.