wild boar

| wild boar | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Wild boar ( Sus scrofa ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Sus scrofa | ||||||||||||

| Linnaeus , 1758 |

The wild boar ( Sus scrofa ) is a cloven-hoofed animals in the family of genuine pig and the root form of the domestic pig . The original distribution area extends from Western Europe to Southeast Asia , due to exposure in North and South America , Australia and numerous islands, it is now almost worldwide distributed.

Wild boars are omnivorous and very adaptable ; In Central Europe, the population is increasing sharply, mainly due to the increased cultivation of maize, and the animals are increasingly migrating to populated areas.

etymology

The name Sus scrofa comes from the Latin sus "pig" and scrofa "the mother pig ".

In French, the name sanglier comes from the Latin singularis (porcus) , which means something like a single (pig) male.

The wild boar and its body parts have their own names and terms in the language of hunters and in hunting customs . The species is referred to here as "wild boar", "black smock" or "sows". Male wild boars are called "boars", a strong, older boar from the age of five or six is called "basse" or "main pig". The female animal is called "Bache", the young animal of both sexes is called a "rookie" from birth to the age of twelve months. From the 13th to the 24th month of life, young wild boars are referred to as "defectors" , more precisely as "overflowers" or "overflowers". The canines in "Gebrech" are the boar as " tusks called". The canines in the upper jaw are called "Haderer", those in the lower jaw are called "rifles".

Appearance

anatomy

When viewed from the side, the body of the wild boar appears compact and massive. This impression is reinforced by the legs, which are short and not very strong compared to the large body mass. In relation to the body, the head also appears almost oversized. It runs out in a wedge shape towards the front. The eyes are high up in the head and are directed obliquely forward. The ears are small and surrounded by a rim of shaggy bristles. The short, stocky and not very mobile neck is only recognizable when wild boars are wearing their summer fur. In winter fur the head seems to merge directly into the trunk. A comb of long bristles runs from the forehead to the back, which can be set up.

The body height decreases towards the hind legs. The body ends in a tail that reaches down to the heel joints and is very mobile. The wild boar uses it to signal its mood by pendulum movements or by lifting it up. Seen from the front, the body looks narrow.

The adult, male animal can be distinguished from the female - when viewed from the side - by the shape of the snout. While it is long and straight in the female, it appears shorter in the male.

denture

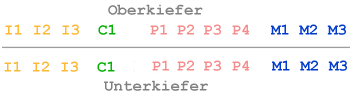

The wild boar has strong dentition with 44 teeth, three incisors ( Incisivi , abbr. "I"), one canine ( Caninus , abbr. "C"), four premolars (abbr. "P") and three molars ( Abbr. "M").

The upper and lower canines of the male curve upwards; in females this occurs only to a small extent in older animals. The canines serve as organs of expression .

The male's lower canines can in exceptional cases reach a length of up to 30 cm. In normal adult males, they are usually 20 cm in length, but rarely more than 10 cm protruding from the jaw. The upwardly curved canines of the upper jaw in the male are much shorter.

hide

Fur of adult and annual animals

The fur of the wild boar is dark gray to brown-black in winter with long bristly outer hairs and short, fine woolen hair . It mainly serves to regulate heat, as the air space enclosed between the hair prevents excessive release of body heat. The smooth outer hairs prevent the skin from being injured when roaming through undergrowth. The woolen hair covers the entire body with the exception of some parts of the head and the lower part of the legs.

In spring, the wild boar loses its long, dense winter coat and has a short, wool-free summer coat with light-colored hair tips. The coat change takes place in a period of about three months and begins in Central Europe in the months of April to May. Wild boars look much slimmer in their summer fur. Wild boars from the previous year start switching to winter fur at the end of July or beginning of August. In adult wild boars, the switch to winter fur does not begin until September. The coat change is completed in November.

However, there are great differences in coat color both regionally and in the same area. Wild boars in the Lake Balkhash region are light sand-colored or even whitish, in Belarus you can find reddish-brown, lighter or even deep black animals, and on the Ussuri you can find light brown and black wild boars.

Spotted wild boar

In wild boar populations, individuals appear again and again with black-brown to black spots of different sizes on a lighter background. Occasionally, black-and-white and black-brown-white spotted boars are observed. In investigations by Heinz Meynhardt in the GDR in the 1970s, spots appeared in around three out of a hundred wild boars. The spotting is inherited recessively. These colorations are attributed to the fact that domestic pigs were kept as grazing pigs for a long time and that there were crosses between wild and domestic pigs.

Polish studies from the same period have shown that wild boars with a strong black and white color have a higher mortality rate compared to their normal-colored conspecifics, because their thermoregulation functions less well.

Pelt of young animals

Newly born wild boars (piglets) have a medium-brown coat, which usually has four to five yellowish longitudinal stripes that extend from the shoulder blades to the hind legs. The animals are spotted on the shoulders as well as on the hind legs. The shape of the stripes and the spots are so individual that young animals can be clearly identified. Their top coat is much softer and woolier than that of older animals and protects the animals less well against moisture, so that high mortality can occur in damp weather. This young animal fur is worn for about three to four months before the animals gradually get the monochrome, brownish young animal fur. It is coarser-haired than the young animal's fur, but still softer than that of the adult animal and also has less well-developed woolly hair. In Central Europe the young develop their first winter plumage in October and November, which then increasingly shows the gray to black coloration of adult animals.

Body weight and height

Weight and size are very different depending on the geographical distribution, the weight also varies depending on the season. As a rough rule, body mass and height increase from southwest to northeast. Wild boars are fully grown from the age of five; in Central Europe, brooks then have a head-trunk length of 130 to 170 cm, boars reach a length of 140 to 180 cm. The maximum live weight of adult brooks in Central Europe is around 150 kg and that of adult boars around 200 kg. At least five years old brooks in the east of Germany weighed between 43 and 95 kg without internal organs ("broken open"), boars without internal organs between 54 and 157 kg. Bachen reached the highest weights there from October to March, boars from August to December. A slaughter weight or slaughter age cannot be defined as the hunt for wild animals is random.

Wild boars in Astrakhan , in the protected area of the Beresina and in the Caucasus are becoming significantly larger and heavier. Males can reach a body length of up to 200 cm and a weight of up to 200 kg. In the 1930s, wild boars weighing up to 260 kg were shot in the Volga Delta and Syr Darya, and a few years earlier even animals weighing 270 kg and 320 kg total weight were recorded. Boars weighing over 300 kg are also known from the Far East of Russia. In the entire distribution area, the body size of the wild boar was reduced by hunting and today animals with a body weight of 200 kg are considered very large. From the Carpathians there are reports of wild boars with 110 cm shoulder height and 350 kg.

distribution and habitat

The wild boar is a wild animal that is distributed throughout Eurasia as well as in Japan and parts of the South Asian island world in around 20 subspecies. The distribution area has changed several times over the millennia. During the cold periods the distribution area shifted several times in an easterly and southerly direction and expanded again in a westerly and northerly direction during warm periods. The species originally came after the last ice age from the British Isles , southern Scandinavia and Morocco in the west across all of central and southern Europe, front and central Asia, north Africa, front and rear India to eastern Siberia, Japan and Vietnam in the east and reached via Sumatra and Java even the Lesser Sunda Islands Bali , Lombok , Sumbawa and Komodo . It is also found on Ceylon , Hainan and Taiwan , but the species seems to be absent on Borneo . The occurrences in Sardinia , Corsica and the Andaman Islands are believed to have been settled there by humans.

In North Africa it was widespread along the Nile Valley to south of Khartoum and north of the Sahara until a few centuries ago . The wild boar is now considered rare in North Africa. The subspecies Sus scrofa libycus , which used to occur from southern Turkey to Palestine, as well as the subspecies Sus scrofa barbarus , formerly native to Egypt and Sudan, are considered extinct. On the Arabian Peninsula , wild boars are only found in the far north.

The original northern limit of the distribution stretched from Lake Ladoga (at 60 ° N) in the northwest, southwards via Novgorod to Moscow and then in a west-east direction over the Volga to the southern Urals (where they reached 52 ° N). From there the border moved slightly to the north again to almost reach Ishim and, further east, the Irtysh at 56 ° N. In the eastern baraba steppe (west Novosibirsk ), the line turned sharply to the south, reaching almost the foothills of the Altai Mountains , they circled and from there via the Tannu-ola Mountains to Lake Baikal moved. From here the border ran north of the Amur to its lower reaches on the China Sea . On Sakhalin , the wild boar has only been proven in fossil form. In dry deserts, high mountains and in the Tibetan highlands , the wild boar is naturally absent south of the line described. It is absent in the arid regions of Mongolia from 44–46 ° N south, in China west of Sichuan and in India north of the Himalayas . In the high mountains of the Pamir and Tianshan you will not find wild boar, in the Tarim Basin and on the lower slopes of the Tianshan, however, the animals are found.

In the last few centuries the distribution of the wild boar has changed mainly due to human interference. With the expansion and intensification of agriculture, the hunting of wild boar also increased, so that, for example, the species was extinct in England at the beginning of the 17th century. The last wild boars were hunted in Denmark at the beginning of the 19th century, until 1900 there were no more wild boars in Tunisia and Sudan, and large parts of Germany, Austria, Italy and Switzerland were also free of wild boars. The German regions in which wild boars were no longer represented until the 1940s include, for example, Thuringia, Saxony, Schleswig-Holstein and Baden-Württemberg.

Reclamation of the range

In the 20th century, wild boars recaptured large parts of their original range. For example, wild boar immigrated again in the 1990s to the Italian Tuscany , which was free of wild boar for a long time due to intensive agricultural management.

In Russia, too, the wild boar was largely extinct in the 1930s and the northern limit of distribution was shifted far south, especially in the west. By 1950, however, the animals had spread again and in many places almost reached the old northern limit of the distribution area again. The area expansion in Eastern Europe is particularly well documented. Around 1930 there were still wild boar populations in the swamp forest areas of Belarus , Ukraine , Lithuania and Latvia . From there the species initially spread along the river plains of Daugava (German: Düna ), Dnepr and Desna and later also along the Oka , Volga and Don . By 1960 wild boars were already widespread again from Saint Petersburg to Moscow ; around 1975 they reached Arkhangelsk to Astrakhan . Wild boars also returned to Finland.

Something similar happened to the west. In the 1970s there were wild boar populations again in Denmark and Sweden , although these were due to animals that broke out of game enclosures. The wild boar has now firmly established itself again in Denmark and Sweden, as it is accepted as a wild stock by the local forest authorities. The wild boar also reached Norway from southern Sweden in 2006 . It is believed to resettle there permanently after having been around since 500 BC. Was extinct. However, the wild boar is currently considered an undesirable species in Norway.

The population development of the last decades can also be seen on the hunting routes . In Germany, for the first time ever, more than 500,000 wild boars were shot between 2000 and 2003. In the 1960s, the annual hunting distance was less than 30,000 animals.

Advancing into urban living space

The adaptability of wild boars is particularly evident in Berlin . Wild boars have conquered the forests close to the city as a habitat and are now also invading the suburbs. Occasionally it makes its way into the city center. In May 2003, for example, two wild boars that appeared on Alexanderplatz had to be shot.

The number of wild boars around Berlin is now estimated (as of 2010) at 10,000 animals. According to estimates by the Berlin Forest Administration, around 4,000 animals feel at home in the immediate city area. They invade the gardens and parks and set up z. T. considerable damage. They also rummage through garbage cans for leftover food. The intelligent animals register very quickly that they are not threatened with hunting in residential areas and occasionally even become diurnal. In some Berlin city parks, for example, young animals can be seen playing in broad daylight. The Berlin Senate has issued a strict feed ban to prevent more wild boars from being lured into the city. Berlin is now considered the capital of wild boars .

In Vienna, wild boars from the Lobau are advancing into residential areas of the Donaustadt district in the east of the city. They come to private gardens and look for food on the compost heap, food provided for cats and dogs, and other discarded edibles. The forestry operations of the municipality of Vienna (MA 49) set up live traps in March 2018 to catch animals, which are then released, especially in the Vienna Woods west of the city. The clever animals notice that conspecifics are being caught and avoid such areas.

Naturalized wild boar populations

About the feral pigs of North America: see main article Razorback .

The wild boar was naturalized for hunting purposes in the United States at the beginning of the 20th century , where it has partly mixed with feral domestic pigs that have lived in the southwestern United States (mainly in Texas ) since the early 16th century . Because of this mixture, there is no clear distinction between domestic pigs and wild boars in North America today. However, animals with a relatively high proportion of wild boar seem to prevail over pigs with a high proportion of domestic pigs, although the stocks are often hunted sharply. States with high wild boar populations include Texas, California , Florida , South Carolina , Georgia , Alabama , Arkansas , Oklahoma , Arizona, and Louisiana .

There are also naturalized wild boar populations in South America. In Argentina, wild boars were naturalized around 1900 and live there between the 40th and 44th parallel.

Wild boar populations, some of which have also mixed with domestic pigs, are also found in New Guinea , New Zealand and Australia as well as in Hawaii , Trinidad and Puerto Rico . Some of the animals were introduced here hundreds of years ago. The first pigs came to Hawaii around 1000 years ago with Polynesian seafarers. Wild boars were introduced into Australia at the beginning of the 19th century to fight snakes, among other things. Today they are considered a plague there - for example, they regularly kill newborn lambs and are therefore considered agricultural pests. Wild boars were also introduced by humans on numerous Southeast Asian islands ( Bismarck and Louisiana archipelago , Solomon and Admiralty Islands and others in the area there).

habitat

Wild boars adapt to a wide variety of habitats. This is due to the fact that they are downright omnivores that quickly open up new food niches. Due to their ability to break up the ground, wild boars have access to food that is not available to other large mammals. Their strong teeth can even break open hard-shelled fruits such as coconuts . They are also excellent swimmers and have good thermal insulation so they can adapt to wetlands too. Due to these abilities, boreal coniferous forest , reed-covered swamps and evergreen rainforest are among the habitats that can be colonized by wild boar.

Their northern distribution is limited by the fact that frozen ground makes it impossible for them to get to underground food reserves. High snow also hampers their movement and thus their foraging. Therefore, wild boars are also absent in high mountain areas.

In the temperate climate of Central Europe, wild boars develop the highest population density in deciduous and mixed forests, which have a high proportion of oak and beech and in which there are swampy regions and meadow-like clearings.

Wild boars adapt to subtropical and tropical climatic conditions by reducing their coat; In addition, they do not form any subcutaneous fat there, which is used as thermal insulation in the northern range. In hot regions, wild boars are dependent on water sources, so deserts are not populated by them.

nutrition

The wild boar rummages through the ground in search of food for edible roots , worms , grubs , mice, snails and mushrooms . In addition to aquatic plants such as sweet flag , wild boars also eat leaves, shoots and fruits of numerous woody plants, herbs and grasses. As omnivores , they also accept carrion and waste. It has been observed that wild boars break open rabbit burrows to eat the young rabbits. Occasionally, eggs and juveniles of ground-breeding birds also fall victim to them. They even eat mussels in dry waters.

The fruits of oaks and beeches play a special role in the food of wild boars in the European range . In years when these trees bear particularly well, so-called fattening years , wild boars live mainly on these fruits for months. If this mast is missing, it is often compensated with maize that is brought in by hunters. In Asia, the same applies to the seeds of various types of stone pine .

The roots of bracken and willowherb are also preferred plant foods in Central Europe . Depending on the season, the roots of wood anemones , snake knotweed , plantain and marsh marigolds also have a larger share of their food. Wild boars also like to graze on clover and eat the aboveground plant parts of sweetgrass, dock , ground elder , bracken, meadow hogweed and oak leaves.

Wild boars can cause significant game damage on agricultural land. They eat all crops that are grown in agriculture in Central Europe. In the case of potatoes , they even differentiate between individual varieties and especially like to eat new potatoes. Wild boars also rummage through grain fields and regularly cause more damage by digging than by eating. The damage that they cause in landscape parks , for example , is primarily burrowing damage. They dig up entire meadows and borders in search of flower bulbs .

Great agricultural damage occurs above all when oaks and beeches have not set enough fruit and the wild boars therefore prefer to search for food in the agricultural fields. This is the main reason wild boars have been hunted so heavily that parts of Europe have been absent for centuries. It is assumed that the fencing of fields , which can already be proven in the Bronze Age, represented an attempt to keep wild boars out of the fields.

However, wild boars also eat insects that spend part of their development time in the ground, and other small animals. The heavy burrowing activity here can also cause considerable damage under the bottom fauna, for example in egg clusters and hibernation areas for lizards . The ransacking of the ground by the wild boar in the context of foraging leads to an increase in biodiversity with a shift in the spectrum to shorter-lived species and thus makes a contribution to botanical species protection. This is attributed to an increased density of germinable plant seeds in soils used by wild boars. Because of the changed properties of the soil that the animals dig, the germination capacity of the plants increases, and the breaking of the dormancy leads to increased growth.

For the distribution of plant seeds after they have been eaten by endochoria , the wild boar is one of the most important vectors for the native flora with 76 of 123 plant species examined .

Locomotion and resting behavior

Gaits, swimming

Resting wild boars usually put the same load on all four legs. At walking pace, the normal form of locomotion is the cloister , in which the diagonally opposite front and rear legs are set forward almost simultaneously. The front and rear legs only leave the floor when the other leg has touched down. The animals can cover 3 to 6 km per hour.

At the trot , the back or front legs leave the ground before the other leg touches the ground: wild boars can keep this gait for a very long time and cover six to ten kilometers per hour. In canter refuge wild boars when they are startled: adult animals lay with each stride up to two meters back, they reach this speed of about 40 km / h can also jump cm high around 140-150. However, they do not maintain this fast run for long and quickly fall back into a trot even if they escape.

Wild boars can also swim very well and are able to cover longer distances; they swim through z. B. has been proven ( photo traps ) the Upper Rhine between the districts of Lörrach and Waldshut , also down from the bend in the Rhine near Basel. They move their legs in a similar way to the trot and only parts of the front and top of the head protrude from the water.

Resting behavior

Wild boars spend a large part of their day resting. At what time of day you do this depends on the respective environmental conditions. To rest, they like to use special resting places, called kettles, which they use both individually and together. Dozing wild boars usually lie with their legs straight, either resting on their stomachs and stretching their front and rear legs forward or backward. The side position in which the legs are stretched out at a right angle is also typical. The crouching position, in which the legs are buckled, only occurs for a short time in wild boars.

The wallowing in mud pools is part of the typical behavioral repertoire of wild boar. Especially in summer it is used for heat regulation. Skin parasites are encapsulated by the mud; the drying mud layer also makes it difficult for stinging insects to access the skin and is scraped off the painting tree , which is located near the wallows. To do this, they lean against the trunk and rub their bodies along it. Trees with coarse bark and / or resinous trees are preferred as painting trees, especially oaks, pines and spruces in Central Europe. These trees show clear traces after prolonged use. Due to the rubbed off mud, the tree is white-gray at the chafed areas, the bark has been removed in parts. To rub their lower body, wild boars stand over tree stumps and rub against them. Boars mark painting trees with their guns.

Scrubbing the body against trees is necessary because wild boars, due to their short and immobile neck, are unable to clean themselves and get rid of insect pests with the help of their teeth.

Reproduction

Mating season

Female young animals - provided they have enough food available - can become sexually mature after 8 to 10 months. Male animals are usually only able to reproduce in their second year of life. Exceptions to this rule have so far only been observed in the United States, where wild boar populations are highly mixed with domestic pigs.

The mating season, also called intoxication season by hunters, depends on the respective climatic conditions; in Central Europe it usually begins in November and ends in January or February - the peak is in December. The start of the mating season is determined by the brooks. Mating can also occur outside of this time. Wild boars can be mated and inseminated all year round. Brooks can be conceptual all year round. With a good food supply, it can happen that yearlings ( defectors ) or even younger animals such as brooks brooks participate in the reproduction and there can be several main and aftermaths in a pack. This can lead to uncontrolled reproduction. Females who have miscarried or whose entire litter died shortly after giving birth may be ready to conceive again.

In German-speaking countries, especially in the hunting press and some hunters, the idea, based on a hypothesis by Heinz Meynhardt , persists that the oldest, reproductive female in the herd, the so-called Leitbache, prevents lower-ranking, young brooks in the herd from reproducing and would act as a "brake on growth" of the population. According to the current research, both are wrong - while the mating season can be synchronized within individual packs, the suppression of reproduction is neither empirically proven nor plausible in view of the wild boar described as r-strategist . In contrast, various studies suggest that a good physical condition of the respective animal due to the nutritional situation is decisive for early sexual maturity and participation in reproduction.

Advertising and pairing

If a male encounters females during the mating season, it smells them in their genital region. When the female is ready to conceive, he pushes her slightly in the belly, against the flanks or on the underside of the neck and circles them. If the female eludes this, the male will follow and attempt to maintain body contact by placing his skull on the female's back or pressing against her flanks. This so-called hustle and bustle can drag on for a long time. If the female is not ready to mate, she will occasionally attack the male. The male then tries to calm the female through nasonasal contact and breathing on. If the female does not want to copulate, she can utter squeaking defense noises. If it is not otherwise possible, it withdraws its genital region by sitting or lying down.

To mate, the female spreads the hind legs stiffly obliquely backwards and turns the tail away to the side. The male rides with his head on her back. In this position, both animals usually remain motionless for five minutes before separating again. A female copulates about six to seven times during the mating season.

Male fights

If males compete for females during the mating season, there are usually hierarchical battles that are highly ritualized.

For posturing of clashing male part including a scrape with the hind legs, splashing of urine and the sharpening of the jaw. When sharpening, the lower jaw is quickly pushed back and forth to the side. The canines of the upper and lower jaw grind against each other. With increasing excitement, this turns into chewing movements or jaw slapping, during which the upper and lower jaws are loudly opened and closed. Saliva foam often forms on the male's mouth. At the same time, the long bristles of the comb are raised, the head is lowered. In the showcase run, the two males circle each other, which often leads to shoulder fights.

If none of the animals has fled by then, a real fight ensues, in which the animals use their lower canines to hit the stomach and side of the body with side-upward blows. The animals can inflict violently bleeding injuries. The fight does not end until one of the animals flees.

Birth of the young

The gestation period of the females is about 114 to 118 days ( donkey bridge : "three months, three weeks and three days"). The young are mostly born in Central Europe between March and May. The newborns are born seeing and hairy (bristles) ( fleeing nest ). Your birth weight is between 740 and 1100 grams. The suckling period of the mostly numerous newborns lasts 2.5 to 3.5 months. If the female belongs to a pack, she will separate from it and go her own way until the young are big enough to keep up with the pack. The bond between brooks and youngsters lasts i. d. Usually 1.5 years.

The female carefully chooses the place for a birth nest before giving birth. These litter kettles are often exposed to the south so that they are heated by the sun. In swampy regions, the female looks for elevations in the ground so that the nest is dry. She pads the nest with grass and then builds a kind of roof. On average, females give birth to around seven young animals. The female usually lies on her side during labor.

During the first days of life of the young animals, which are sensitive to cold and moisture, the female usually remains in the birth nest. Depending on the weather conditions, the female leaves the nest with her young after one to three weeks. Females vigorously defend their young. It can also lead to attacks on people.

The mortality among young animals is very high. Above all, they die if there are cold spells and periods of wetness during their first three weeks of life, as their heat regulation is not yet fully developed. Mortality also depends on how many predators live in the area. In predator-free areas, an average of 75 out of 100 young survive the first year (those that do not survive usually die in the first month of life), in areas where wolves, bears and lynxes share their habitat with wild boars, the figure is only around 30 from 100.

Social behavior

Wild boars live together in mother families, in harems or in groups of animals from previous years. Male animals in particular live solitary. The most typical form of coexistence is the mother family, which consists of a female with her last offspring. Occasionally the female offspring of the previous year stays with the mother and then sometimes leads their own offspring. The original mother is the leader in such a clan association. Foreign wild boars are usually not included in such a group. If different mother families meet, they keep their distance from one another. These groups break up when the food supply is insufficient, when they are broken up by hunting or other disturbances, or when the lead animal dies. Due to the high mortality of the young animals, the group sizes fluctuate very strongly. Groups of more than 20 animals are exceptional in Central Europe.

The previous year's males are driven out of the group by the female and then usually live in their own association for at least one year. Here, too, there are no alliances with previous year's animals from other groups. The hierarchy between the individual animals in such a group has been fought out since the young animal age.

From the age of two, males usually roam the territory as solitary animals. During the mating season from November to January, they join mother families individually. However, the contact between the male and the mother family remains loose - he does not rest in the common bed and the female lead leads the group.

Occasionally, groups of animals from the previous year can also be observed in which male and female animals live together. They occur when the mother was either shot down or died of natural causes. Such atypical groups dissolve in the next mating season.

mortality

Life expectancy

Physically fully grown wild boars are between five and seven years old; however, only a few individuals reach this age.

In lightly hunted populations, life expectancy is between 3–6 years, while in more heavily hunted populations it drops to 2–3 years. The annual death rate is 50%. This is a low value, especially for freshlings. Hunting is the main cause of death in Europe, diseases only play a minor role. Physically mature wild boars make up only a small part of the wild boar population. Few animals get any older. In captivity, on the other hand, wild boars reach a much higher age. Wild boars that have reached the age of 21 are documented.

Predators

The natural enemies of the wild boar include tigers , wolves and brown bears . The lynx , fox , wildcat and eagle owl also occasionally hit young animals.

Wild boars are a major prey for wolves, although the proportion varies depending on the habitat. In a study carried out in northern European Russia in the early 1980s , 47% of wolf excrement contained wild boar remains. In other regions of Russia, similar studies came to the conclusion that wild boars account for up to 80% of the prey in spring and summer and 40% in autumn. When hunting, wolves chase the group of wild boars over a longer distance and try to separate one animal from the group. Young animals and previous year's animals in particular fall victim to them. Adult wild boars can, if cornered, defend themselves against wolves.

According to studies in Eastern Europe, brown bears hunt wild boars when they do not have other food reserves or when they do not go into hibernation due to insufficient fat reserves. They then sneak up on the wild boars that rest in the nest at night or attack them in their wallow. In winter, however, they also track sick and weakened animals over long distances.

Lynx, fox, wild cat and eagle owl only play a subordinate role as predators compared to wolf, Siberian tiger and brown bear. They mainly hunt newly born or weakened young animals. It is reported that the fox occasionally follows females with young animals in order to hunt any young animals that may remain behind.

Diseases

Wild boars are considered to be a constant reservoir of pathogens and are the main carriers of classic swine fever to domestic pig populations. In 2002, 451 cases of wild boar were reported in Germany, which also led to increased hunting pressure. However, the infestation situation has decreased in recent years. Cases of African swine fever have been known in the east of the European Union since 2014 . At the beginning of 2019, the construction of a wild boar fence on the German-Danish border began. According to the responsible Danish nature authority, this is to prevent the transmission of African swine fever.

Wild boars are hosts for trichinae . For this reason, wild boar meat must be subjected to a trichinae test before it is used. Positive results are very rare; the examination is necessary, however, since an illness can be fatal for humans in extreme cases.

15% of the wild boars killed in Germany are carriers of the hepatitis E virus . The extent to which it is transmitted to humans is still unclear. Wild boars on the Iberian Peninsula have been identified as carriers of the tuberculosis bacterium. In an experiment carried out in 2012, wild boars transmitted Ebola viruses to primates - without direct contact - without becoming fatally ill themselves.

Systematics

Development history

The oldest known fossil finds that can be clearly assigned to the wild boar come from the late Miocene in Europe (about 6 million years ago) and in North America from the early and middle Pleistocene (about 1.8 million years ago).

Within the genus Sus , the most closely related species to the wild boar is very likely the dwarf wild boar ( Sus salvanius ). These two species are opposed to all other Sus species as bearded and pustular pigs . However, their internal relationships are still unclear.

Subspecies

In addition to the nominate form , a number of subspecies have been described. These are differentiated based on the basilar length of the skull and the proportions of the tear bone . The length of the tear bone decreases from west to east, and its height increases. The entire skull becomes shorter and higher. The more northerly and northwestern species also have increasingly thicker and longer hairs. Wild boars living on islands are generally smaller.

The following subspecies are distinguished:

- Sus scrofa scrofa - the nominate form , which is widespread in Western and Central Europe as far as the Pyrenees and the Alps and as far as northwestern Slovakia . The subspecies is medium-sized, dark with rust-brown fur.

- Sus scrofa castillianus - is the subspecies widespread on the Iberian Peninsula.

- Sus scrofa meridionalis - was the subspecies native to Corsica and Sardinia . It is now considered to be eradicated.

- Sus scrofa majori - the subspecies widespread on the Italian peninsula. It is relatively small and dark. In the north of Italy it has now been replaced by the scrofa subspecies .

- Sus scrofa reiseri - from the area of the former Yugoslavia

- Sus scrofa barbarus - the now rare subspecies that was originally widespread in Morocco , Algeria and Tunisia .

- Sus scrofa sennaarensis - was the now extinct wild boar subspecies that was native to Egypt and Sudan.

- Sus scrofa libycus - was the subspecies from southern Turkey to Israel and Palestine. It has also been eradicated by hunting.

- Sus scrofa attila - is the subspecies native to the Caucasus, Southeast Europe, Asia Minor, northern Persia and along the northern coast of the Caspian Sea, which is larger and heavier than the Central European subspecies. The fur, on the other hand, is a little lighter.

- Sus scrofa nigripes - is the Central Asian subspecies found in Kazakhstan, southern Siberia, eastern Tianshan, western Mongolia, and possibly Afghanistan and southern Iran. The subspecies is quite large on average, but shows a wide range of variation in this regard. The light fur color contrasts with the black legs.

- Sus scrofa sibiricus - the subspecies living in the Baikal area and northern Mongolia . It is considered a relatively small subspecies. The fur is dark brown, almost black.

- Sus scrofa ussuricus - the so-called "Ussurian wild boar", which is one of the largest subspecies. The basic color is variable, but mostly dark, a white band extends from the mouth to the ear. Inhabits the Amur and Ussuri area.

- Sus scrofa leucomystax - is the wild boar that lives in Japan.

- Sus scrofa riukiuanus - the endangered wild boar of the Ryukyu Islands in southwestern Japan

- Sus scrofa cristatus - the Indian wild boar is the subspecies living in India and Indochina that has a shortened facial skull.

- Sus scrofa vittatus - primitive subspecies, inhabits the arch from the Malacca peninsula over the Sunda Islands to Komodo .

- Sus scrofa timorensis - common in Timor.

- Sus scrofa nicobaricus - from the Nicobars

- Sus scrofa andamanensis - from the Andamans

- Sus scrofa chirodontus - from southern China and Hainan

- Sus scrofa taivanus - from Taiwan

- Sus scrofa moupinensis - from central China

- Sus scrofa papuensis - from New Guinea

genetics

European wild boars usually have 2n = 36 chromosomes . Domestic pigs, on the other hand, have 2n = 38 chromosomes. The Japanese wild boar Sus scrofa leucomystax and populations in the former Yugoslavia have the same number of chromosomes as the domestic pig. In Dutch wild boar populations, animals with 2n = 37 chromosomes are relatively common and those with 2n = 38 are extremely rare. The arms of a submetacentric (between middle and end) chromosome of the wild boar correspond to two telocentric chromosomes (chromosomes with a terminally located centromere ) of the domestic pigs. In the course of the domestication of the wild boar, fission probably led to an increase in the number of chromosomes. However, there is also the possibility that the original number of chromosomes in the wild boar was 2n = 38 and that a few submetacentric chromosomes were formed by centric fusion of two pairs of telocentric chromosomes. The Japanese and Yugoslav subspecies would then represent the original state.

Crosses between wild pigs and domestic pigs result in fertile offspring, even if the number of chromosomes in the parent animals is different.

Danger

From a global perspective, the wild boar is listed as Least Concern (not endangered) by the International Union for Conservation of Nature ( IUCN) in the Red List of Endangered Species . Local threats are on the decline.

Man and wild boar

Wild boar and domestic pig

In the large area of the wild boar domestication has occurred several times independently of one another. Domestication of the wild boar has been accompanied by a decrease in size, similar to that of sheep and goats . Archaeological finds of pig bones, which are significantly below the range of variation of wild boar bones, are therefore considered to be evidence of wild boar domestication. The oldest secure evidence of domestication has been found in south-east Turkey . In early Neolithic settlements from the first half of the 8th millennium BC Excavations have brought to light pig bones, which in their proportions differ significantly from wild boar. In Iraq and Europe, certain evidence dates back to 7000 BC. Independently of this, the domestication of the wild boar took place in China , where the oldest bone finds point to a domestic animal husbandry of the wild boar in the 6th millennium BC. Point out. In Thailand archaeological evidence suggests domestication to the 4th millennium BC. To date.

Domestication in Central Europe has resulted in pigs that in the Middle Ages often only had a withers height of 75 cm. In their appearance - dense body hair, elongated head, standing mane - they were still very similar to the wild boar:

“Up until the 18th century, the life of European domestic pigs did not differ fundamentally from that of wild boars. The keeping conditions did not protect them from climatic rigors. Most of the food they had to look for in the woods themselves, and they were only given rubbish. In addition, a wild boar may have occasionally entered your enclosure to cover a sow. The result was that up to that time, domestic pigs hardly differed in type from wild boars. They were long-legged, slender animals with a long, straight head and a distinct bristle comb on their backs. Around 1800 the age of slaughter pigs in Germany was 1½ years; their weight at that time was 50 kg. "

Today's domestic pigs, such as the Swabian-Hällische Landschwein or the German Edelschwein , are relatively modern breeds. They emerged after the acorn-fed practice was increasingly discontinued. The first modern breed of pig originated in England around 1770.

The wild boar as game

The wild boar was one of the most important hunting game for the Mesolithic people . Based on archaeological findings, it is believed that wild boars made up around 40 to 50% of the hunted prey in Central Europe. Our ancestors used pitfalls and hunted the easy-to-kill young animals and previous year's animals with bows and arrows.

Hunting a full-grown boar required courage and skill. An injured adult wild boar also attacks humans and especially the male animals with their long canine teeth are able to inflict fatal injuries on humans. It was therefore considered a royal test of courage to hunt wild boar only with the so-called boar pen - a hunting spear. Charlemagne's successful hunt for a boar is accordingly also honored in the St. Gallen manuscript Carolus Magnus et Papa Leo from 799.

As countless paintings and handicrafts show, wild boar hunting with horses and hunting dogs was the usual way of hunting. At the beginning of the 17th century, 900 large hunting dogs were kept at the Herzogenhof in Württemberg and were used to hunt wild boar. The more valuable of these dogs, also known as " bastards " or "pig dogs ", were protected against attacks by wild boars with wide collars and sometimes even mail shirts. The dogs' job was to chase the boar until it tired and then hold it in one place until the hunter killed it from a close range. In these wild boars, people, horses and dogs were regularly seriously and sometimes fatally injured by attacking wild boars.

The development of firearms made hunting wild boar easier. There was no longer any need to face a wild boar hitting wildly with its tusks. Nevertheless, especially in the Baroque era, the hunt for the wild boar was an integral part of court ceremonies. Hunting on horseback was still a princely amusement, but the animals were often herded in front of the rifles of court society in so-called hunt or suction gardens. The hunted animals also played a role in supplying the population with meat. In 1669, for example, the “Provision and Smoke House of the Jägerhof Dresden” sold 616 shot animals to the population; in Prussia the citizens of the cities were forced to buy wild boars hunted from the royal court. On the other hand, there was the massive agricultural damage that the wild boar caused in the fields. As a rule, the farmers were not allowed to kill the wild boars that invaded their fields - they were only allowed to protect their cropland with clubs.

This changed with the decline of absolutism . Hunting restrictions on wild boar were lifted and from the last third of the 18th century ordinances were passed in many Central European countries, according to which wild boars were only allowed in zoos or game gates. In the middle of the 19th century the wild boar was therefore no longer represented in numerous Central European regions. This was largely due to the fact that, as a result of the revolution of 1848, hunting rights were tied to property. The hunting owner had to replace the damage caused by game and this led to a massive decimation of the wild boar population. The Prussian Wildlife Damage Act of 1891, for example, required those entitled to hunt to fully compensate for the damage caused by wild boar if they could be accused of having intended to protect them. It was already rated as a protection intention if the person entitled to hunt did not shoot a female with young animals.

As described in the section “Distribution” , many regions of Central Europe were no longer populated by wild boars in the 1940s. The fact that hunting was only permitted to a limited extent in the first post-war years, especially in Germany, contributed to the spread of wild boar. The increased cultivation of maize also increases the number of wild boar routes. In the hunting year 2007/08 447,000 animals were shot in Germany, in 2010/11 it was 579,000, which corresponds to an increase of 30% within three years. The trend is unbroken; in 2015/16 the rate was 610,600. However, the annual route varies considerably in the federal states. The comparison alone between the city-states of Berlin with over 1,500 kills, Hamburg with 128 and Bremen with only two shows this clearly. The wild boar is now the second most common hairy game that can be hunted after the deer in Germany, in Austria it is still in fifth place, in Switzerland in sixth place (2015 also here in fifth place).

Wild boar as venison

Wild boars are processed into game as far as possible . The meat of wild boar is still the most sought after. According to the German Hunting Association, the volume in Germany in 2016/17 was 13,900 tons. The calculated value of the venison is over € 92.3 million. As an omnivore, wild boar is subject to an official inspection (inspection) for trichinae . Since the Chernobyl nuclear disaster , tests for radioactive contamination from 137 Cs have also had to be carried out in southern regions of the Federal Republic , provided that the meat is sold. According to a report by the Telegraph , the radiation exposure of wild boars in Saxony in 2014 was still so high that 297 of 752 animals killed exceeded the limit of 600 Bq / kg and had to be destroyed. Also in certain areas of Sweden ( Uppsala län , Gävleborgs län and Västmanlands län ) 69 of 229 wild boars hunted showed values above 1500 Bq / kg, the maximum value in the analysis carried out in 2017/2018 was around 40,000 Bq / kg. Due to their feeding behavior, wild boars are significantly more exposed than other wild animal species. However, the contamination is decreasing. While the nationwide IMIS measuring program from 2014 to 2016 determined values of up to around 2,500 becquerels per kilogram for wild boars, the maximum values from 2016 to 2018 were up to around 1,300 becquerels per kilogram. Most of the values were significantly lower.

In general, freshlings weighing less than 15 kg are only shot to control epidemics (e.g. swine fever). Defectors and not too old animals of both sexes provide good venison . Older pieces are made into sausage. Boars in the intoxication time are hardly to be used.

Behavior towards people

Wild boars live predominantly in rural regions, but if the conditions are suitable, they can also permanently colonize settlements, including large cities, so they do not generally avoid regions with high population concentrations. If there is frequent contact with people, they show behavioral adaptations. Often the period of nocturnal activity increases, but habituation processes can occur, mainly due to a lack of hunting in cities , whereby the animals lose their fear of humans. This is especially true if they are also fed.

Experience in Berlin shows that parts of the population often reject hunting in urban areas out of sympathy for the animals and for reasons of animal welfare, but also because of the damage it causes in gardens and green spaces. In addition to hunting, the main focus here is on advising citizens on how to deal appropriately with wild boars in their living area. However, a survey in Barcelona (Spain) showed that massive shooting of wild boars in the city was overwhelmingly rejected even by those citizens who had previously had negative experiences with them. In Berlin, around a quarter of those questioned in severely affected areas showed sympathy for a radical fight.

Direct attacks by wild boars on humans are rare, but have shown an increasing tendency in recent decades. Of 412 cases analyzed worldwide, only a quarter took place during a hunt, then mostly through shot animals. Around half (49%) of the attacks outside of the hunt took place without prior provocation through personal behavior such as threat, also half (52%) at night. In cases where gender could be determined, most (82%) of the attacks were from boar. In 69% of the cases there were injuries, fatal injuries occurred, but remained a few isolated cases. Only in a few cases (around 10%) were humans accompanied by dogs. Due to the body size, mostly superficial injuries on the legs and in the lower trunk area predominate. More frequent than attacks on people are accidents with wildlife with cars, mostly on roads with moderate traffic at night. In Berlin alone there were 653 accidents involving wild boars in 2004/2005. Other problems related to damage caused by digging in gardens and parks and occasional conflicts with waste-recycling animals.

Wild boars are robust with one another and can inadvertently seriously injure people even without aggressive intentions. We therefore generally advise against keeping wild boars as pets.

Trained wild boars

In Périgord (France) specially trained wild boars are used to search for truffles .

In the 1980s, a wild boar trained in the Hildesheim area achieved worldwide fame and was the first pig in the service of the police to be included in the Guinness Book of Records : after training by a service dog handler, the sniffer wild boar Luise of the Lower Saxony police was able to dig buried explosives and find drug samples as well as drug sniffer dogs . The Bache was in the service of the police from 1984 until the retirement of her instructor and guide in 1987. Because of her extensive public relations work, she was only involved in a police operation in four cases , and she found it twice.

Wild boars in literature

The hunt for the defensive wild boar has always been a topic of literature. This ranges from the deeds of Herakles , who caught the Erymanthian boar , to the Nibelungenlied and the Greek tradition of the wild boar hunt of the Atalante and Meleager ( also captured in paintings by Peter Paul Rubens ) to the depiction in the comic series Asterix .

Even in the stories of Homer it is reported how the Greek goddess of the hunt, Artemis, sent a wild boar to the earth in revenge, which devastated the fields and vineyards. The Roman poet Ovid described the damage caused by burrowing wild boars in farmers' fields. In the Germanic Edda , the heroes hunt the boar Sährimnir every day , who rises the next morning to be hunted again. The wild boar fight also appears as a test of courage in fairy tales. In the fairy tale of the brave little tailor , the skinny little tailor uses a clever trick to catch the wild boar, which even the hunters were afraid of (see also The Singing Bone ).

In the comic series Asterix , whose plot in Gaul in Roman times around the year 50 BC. Under Julius Caesar , wild boars are the favorite dish not only of the main characters Asterix and Obelix , but also of all the inhabitants of the Gallic village, who bitterly resisted the Romans. Almost every issue of the comic series ends with the entire village reconciling and celebrating over wild boar dinner.

In the novel Hannibal by Thomas Harris wild pigs play a role in the plans for vengeance Mason Vergers, a victim of Doctor Lecter. He has a breed of wild boar bred, particularly wild and even bloodthirsty, to be used as a murder weapon against Doctor Lecter.

Wild boars in art

Wild boar as heraldic animal and namesake for localities

The wild boar was often used as a heraldic animal and was also the inspiration for the naming of localities. Well-known examples are the district town of Eberswalde northeast of Berlin, the multiple place names Eberbach or Ebersbach , Everswinkel in Münsterland or Eversberg in Sauerland. A boar with stately tusks adorns the coat of arms of the district of Ebersberg and the district town of Ebersberg in Upper Bavaria; The place Ebermannstadt in Upper Franconia also uses a picture of the animal.

The coat of arms of the Wolfsburg district of Vorsfelde shows a jumping black boar over green ground on a silver background. It is a talking coat of arms , because the wild boar embodies the part of the name Vor in the place name Vorsfelde. Dat Vor is a term from Low German and stands for a lean pig . The coat of arms in its present form first appeared around 1740. It arose from the Vorsfeld town seal , on which a jumping wild boar can be traced back to 1483. The adoption as a heraldic animal is probably also based on the frequency of wild boar in the nearby Drömling forests . Since 1952 there has been a boar as a stuffed heraldic animal in a showcase in the former Vorsfeld town hall (today the administrative office of the city of Wolfsburg) that was shot near the village.

The old noble family Bassewitz , resident in Mecklenburg, derives its name from the word "Basse", a term used in the hunter's language for a powerful boar. They also bear the boar in the family coat of arms.

The boar's head is the trademark of the Hardenberg-Wilthen spirits factory in Nörten-Hardenberg (“Hardenberger”). It gave itself this trademark because of the boar as the heraldic animal of the Counts of Hardenberg , who have their headquarters there.

Boar as heraldic animal for Wolfsburg-Vorsfelde

Coat of arms of the von Bassewitz family

Coat of arms of Schweinspoint

Coat of arms of those von Hardenberg

Wörlitz coat of arms

literature

- Norbert Benecke: Man and his pets - the story of a relationship that is thousands of years old . Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-88059-995-5 , pp. 248-260.

- Lutz Briedermann: Wild boar . 2nd, edited edition. Deutscher Landwirtschaftsverlag, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-331-00075-2 .

- H. Gossow: Wild ecology. (Reprint of the last edition of the FSVO.) Verlag Kessel, Remagen-Oberwinter 2005, ISBN 3-935638-03-5 .

- Heinz Gundlach : Brood care, brood care, behavioral ontogenesis and daily period in the European wild boar (Sus scrofa L.). In: Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie . Volume 25, No. 8, 1968, pp. 955-995 (abstract on onlinelibrary.wiley.com . Retrieved August 27, 2017).

- Ilse Haseder , Gerhard Stinglwagner : Knaur's large hunting dictionary. Augsburg 2000, ISBN 3-8289-1579-5 .

- Lutz Heck : The wild boars . Paul Parey Publishing House, Hamburg 1980/1985, ISBN 3-490-06612-X .

- Rolf Hennig : Wild boar. Biology, behavior, tending and hunting. 7th, revised edition. (New edition). BLV, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-8354-0155-6 .

- VG Heptner: Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol. I Ungulates . Leiden / New York 1989, ISBN 90-04-08874-1 .

- Heinz Meynhardt : Wild boar report. My life among wild boars. 8th, revised edition. Neumann, Leipzig / Radebeul 1990, ISBN 3-7402-0080-4 .

- F. Müller, DG Müller (Hrsg.): Wildlife information for the hunter. Volume 1: Haarwild . (Reprint of the earlier edition from Jagd + Hege ). Verlag Kessel, Remagen-Oberwinter 2004, ISBN 3-935638-51-5 .

- Michael Petrak : Wild boar . Biology, population reduction, social structures, game damage containment, swine fever . (= Game and dog. Exclusive. 22). Parey, Singhofen 2003, ISBN 3-89715-022-0 .

- Cord Riechelmann: Wild animals in the big city . Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-89479-133-0 .

- Hans Hinrich Sambraus: Color atlas of farm animal breeds . Ulmer, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8001-3219-2 .

Film documentaries

- Wild boar Report , a TV documentary series of Heinz Meynhardt , 1974-1977

- Wild boar stories , ten-part television series by Heinz Meynhardt

- The wild boars in the Teutoburg Forest . 45 min. (Series: Expeditions into the Animal Kingdom ), first broadcast on March 26, 2008 (NDR); Author: animal filmmaker Günter Goldmann

Individual evidence

- ↑ W. Oliver, K. Leus: Sus scrofa . The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T41775A10559847. doi: 10.2305 / IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T41775A10559847.en

- ↑ Entry sanglier . Website of the Center National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales. (French)

- ↑ Haseder, p. 280.

- ↑ Ilse Haseder, Gerhard Stinglwagner, p. 732.

- ↑ Edgar Böhm: Hunting practice in the Black Forest area . Leopold Stocker Verlag, Graz 1997, p. 29 ff.

- ↑ Hans Stubbe (Ed.): Book of Hege. Volume 1: Haarwild. Verlag Harri Deutsch, Thun / Frankfurt am Main 1988, pp. 254-255.

- ^ Ronald M. Nowak: Walker's mammals of the world . 6th edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1999, ISBN 0-8018-5789-9 (English).

- ↑ Operations and observations of villsvin i Østfold. (PDF; 173 kB) In: nhm.uio.no. May 7, 2011, accessed October 7, 2011 (Norwegian).

- ↑ Wild boars eat their way through Norway. In: badische-zeitung.de. May 7, 2010, accessed October 19, 2011 .

- ↑ Wild boar hunt at Alexanderplatz. In: morgenpost.de. May 27, 2015, accessed June 14, 2015 .

- ↑ No feeding. Press release from the Berlin Senate Department for Urban Development and the Environment from March 11, 2010.

- ↑ Live traps for wild boars in the Danube city. orf.at, March 13, 2018, accessed on March 13, 2018.

- ^ S. Brandt, É. Baubet, J. Vassant, S. Servanty: Régime alimentaire du Sanglier en milieu forestier de plaine agricole . In: faune sauvage . tape 273 , September 2006, p. 20-27 . (French)

- ↑ Olaf Simon, Wolfgang Goebel: On the influence of the wild boar (Sus scrofa) on the vegetation and soil fauna of a heathland. ( Memento of April 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 2.7 MB). In: Natural and cultural landscape. Volume 3, Höxter / Jena 1999, pp. 172-177.

- ↑ Natasha KE Sims: The ecological impacts of wild boar rooting in East Sussex. (PDF; 3.7 MB) PhD thesis, published by British Wild Boar. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ^ Thilo Heinken, Goddert von Oheimb, Marcus Schmidt, Wolf-Ulrich Kriebitzsch, Hermann Ellenberg: Hoofed game spreads vascular plants in the Central European cultural landscape: a first overview. (PDF). Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ Leonid Baskin, Kjell Danell: Ecology of Ungulates: A Handbook of Species in Eastern Europe and Northern and Central Asia . Springer, Berlin 2003, ISBN 978-3-540-43804-5 , pp. 15-38 .

- ↑ Kevin Morelle, Tomasz Podgórski, Céline Prévot, Oliver Keuling, François Lehaire: Towards understanding wild boar Sus scrofa movement: a synthetic movement ecology approach: A review of wild boar Sus scrofa movement ecology . In: Mammal Review . tape 45 , no. 1 . The Mammal Society and John Wiley & Sons , January 2015, p. 15–29 , doi : 10.1111 / mam.12028 ( wiley.com [accessed December 19, 2019]).

- ↑ Katrin Ganter: Deer, badger, Mr. Klumpp. In: Sunday . Markgräflerland edition , April 13, 2014.

- ^ Rolf Hennig: Wild boar . Biology, behavior, tending and hunting . 1st edition. BLV-Verlagsgesellschaft, 1981, ISBN 3-405-11329-6 , p. 23 .

- ^ Rolf Hennig: Wild boar . Biology, behavior, tending and hunting . 1st edition. BLV-Verlagsgesellschaft, 1981, ISBN 3-405-11329-6 , p. 22nd ff .

- ↑ a b c Leitbachendiskussion. (No longer available online.) In: Wildtierportal Bayern. Archived from the original on January 8, 2019 ; accessed on January 8, 2019 .

- ↑ Friedrich Völk: Wild boar hunting: Traditional recommendations and their goals . In: The sight . No. 12 , 2014, ISSN 0003-2824 , p. 18th f . ( bundesforste.at [PDF; accessed on January 9, 2019]).

- ↑ Stefan Schmitt: Legendary streams. (No longer available online.) In: ZEIT ONLINE. March 19, 2009, archived from the original on January 8, 2019 ; accessed on January 8, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Felix Knauer: Young before old or old before young? - Is it crucial for successful wild boar reduction? In: Teaching and Research Center for Agriculture Raumberg-Gumpenstein (Ed.): Report on the 19th Austrian Hunters Conference 2013 on the subject of regulation of red deer and wild boar - challenges and obstacles . 2013, ISBN 978-3-902559-87-6 , pp. 5 ff . ( bundesforste.at [PDF; accessed on January 8, 2019]).

- ↑ Oliver Keuling: Wild boar: Hunting strategies and avoidance of damage . In: Teaching and Research Center for Agriculture Raumberg-Gumpenstein (Ed.): Report on the 19th Austrian Hunters Conference 2013 on the subject of regulation of red deer and wild boar - challenges and obstacles . 2013, ISBN 978-3-902559-87-6 , pp. 11 ff . ( bundesforste.at [PDF; accessed on January 8, 2019]).

- ↑ Walter Arnold: Sows without end - what to do? In: Pasture . No. 12 , 2012, ISSN 1605-1335 , p. 19 ( vetmeduni.ac.at [PDF; accessed on January 8, 2019]).

- ^ Frank Christian Today: Strategies of Wild Boar Hunting - Management or Reduction . In: Eco Hunting . No. 4 , 2016, ISSN 1437-6415 ( wildoekologie-heute.de [accessed on January 8, 2019]).

- ↑ Ilse Haseder, Gerhard Stinglwagner: Knaurs Großes Jagdlexikon. Augsburg 2000, ISBN 3-8289-1579-5 , p. 735.

- ↑ When brooks pig in the litter kettle online. In: dw.com , Deutsche Welle , September 15, 2003, accessed on March 26, 2016.

- ↑ S. Servanty, J.-M. Gaillard, F. Ronchi, S. Focardi, É. Baubet, O. Gimenez: Influence of harvesting pressure on demographic tactics: implications for wildlife management . In: Journal of Applied Ecology . tape 48 , 2011, p. 835-843 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1365-2664.2011.02017.x . (English)

- ^ O. Keuling et al.: Mortality rates of wild boar Sus scrofa L. in central Europe . In: European Journal of Wildlife Research . June 2013, doi : 10.1007 / s10344-013-0733-8 . (English)

- ↑ Risk assessment of 07/12/17 on African swine fever. Website of the Friedrich Loeffler Institute. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ↑ Denmark's wild boar fence: the first kilometers are up. ndr.de, accessed on April 29, 2019.

- ↑ Hepatitis E virus in German wild boars. Information No. 012/2010 of the Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) from March 1, 2010. In: bfr.bund.de , (PDF; 47 kB).

- ^ V. Naranjo, C. Gortazar, J. Vicente, J. de la Fuente: Evidence of the role of European wild boar as a reservoir of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex . In: Vet. Microbiol. tape 127 , no. 1–2 , February 2008, pp. 1–9 , doi : 10.1016 / j.vetmic.2007.10.002 , PMID 18023299 .

- ↑ Ebola transmitted by wild boars. In: aerzteblatt.de . November 16, 2012, accessed December 27, 2014 .

- ↑ Wolf Herre: Pets - seen from a zoological perspective. Springer-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-642-39394-5 , p. 312 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ Memorandum of Understanding of: Mammals of Switzerland / Mammifères de la Suisse / Mammiferi della Svizzera. Springer-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-0348-7753-4 , p. 429 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ Sus scrofa (Eurasian Wild Pig, Ryukyu Islands Wild Pig, Wild Boar). In: iucnredlist.org , Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ↑ Sambraus, p. 277.

- ↑ Annual route for wild boar 2015/16 , accessed on July 29, 2017.

- ↑ Annual hunting route Federal Republic of Germany 2015/16. Website of the German Hunting Association. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ↑ Popular food: venison. German Hunting Association, December 18, 2017, accessed on October 25, 2019 .

- ↑ Appearance of game. German Hunting Association, accessed on October 25, 2019 .

- ↑ lfu.bayern.de

- ^ Justin Huggler: Radioactive wild boar roaming the forests of Germany. In: The Telegraph . September 1, 2014, accessed September 4, 2014.

- ↑ Radioaktivt cesium i vildsvin , accessed on March 30, 2020 (Swedish).

- ↑ Radioactive contamination of mushrooms and game , accessed on March 30, 2020.

- ↑ a b c Jesse S. Lewis, Kurt C. VerCauteren, Robert M. Denkhaus, John J. Mayer: Wild Pig Populations along the Urban Gradient. In: Kurt C. VerCauteren, James C. Beasley, Stephen S. Ditchkoff, John J. Mayer, Gary J. Roloff, Bronson K. Strickland (Eds.): Invasive Wild Pigs in North America. Ecology, Impacts, and Management. CRC Press, Boca Raton 2019, ISBN 978-0-367-86173-5 , Chapter 19.

- ↑ Haruka Ohashi, Masae Saito, Reiko Horie, Hiroshi Tsunoda, Hiromu Noba, Haruka Ishii, Takashi Kuwabara, Yutaka Hiroshige, Shinsuke Koike, Yoshinobu Hoshino, Hiroto Toda, Koichi Kaji: Differences in the activity pattern of the wild boar to Sus scrofa related human disturbance. In: European Journal of Wildlife Research. Volume 59, 2013, pp. 167-177. doi: 10.1007 / s10344-012-0661-z

- ↑ L. Wittich: Wildlife Presence and Wildlife Activity in Urban Space. In: H. Hofer, M. Erlbeck (Hrsg.): Wildlife Management in Urban Areas? Wild animals in the field of tension between animal welfare, hunting law and nature conservation. Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW), Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-00-021684-8 , pp. 16-20.

- ↑ Carles Conejero, Raquel Castillo-Contreras, Carlos González-Crespo, Emmanuel Serrano, Gregorio Mentaberre, Santiago Lavín, Jorge Ramón López-Olvera: Past experiences drive citizen perception of wild boar in urban areas. In: Mammalian Biology. Volume 96, 2019, pp. 68-72. doi: 10.1016 / j.mambio.2019.04.002

- ↑ a b York Kotulski, Andreas König: Conflicts, crises and challenges: Wild boar in the Berlin City - A social empirical and statistical survey. In: Natura Croatica. Volume 17, No. 4, 2008, pp. 233-246.

- ^ A b John J. Mayer: Wild Pig Attacks on Humans. In: Proceedings of the Wildlife Damage Management Conference. Volume 15, 2013, pp. 17-25.

- ↑ Abdulkadir Gunduz, Suleyman Turedi, Irfan Nuhoglu, Asım Kalkan, Suha Turkmen: Wild Boar Attacks. In: Wilderness and Environmental Medicine. Volume 18, 2007, pp. 117-119.

- ↑ Henrik Thurfjell, Göran Spong, Mattias Olsson, Göran Ericsson: Avoidance of high traffic levels results in lower risk of wild boar-vehicle accidents. In: Landscape and Urban Planning. Volume 133, 2015, pp. 98-104. doi: 10.1016 / j.landurbplan.2014.09.015

- ↑ The newborn as a foundling. Information on how to deal with found newborns. In: wildschweine.net , accessed on January 14, 2017.

- ^ Wild boar Luna - Star on the farm. Report of hand rearing on a farm. In: badische-zeitung.de , August 19, 2011, accessed on January 14, 2017.