Notation (music)

When notation is called in music the graphical detention of musical parameters such as pitch , - duration and - loudness in a developed to mainly of notes existing notation . On the one hand, it serves to document already known pieces of music in writing, and thus partially replaces the tradition with auditions or auditions. The pin rollers and disks in the barrel organ and music box can also be viewed as documentation of a melody , but apart from that, musical notation was that until the inventionSound recording is the only way to capture music you have heard in anything other than memory. The second great use of musical notation is to express new melodies and other musical ideas exclusively in writing. Only the possibility of conveying an idea without having to carry it out themselves enables individuals to create extensive and complex works.

The modern western musical notation

Elements of the notation

The graphic elements of modern musical notation are initially the notation system made up of five lines, on which, in addition to information about tempo , time signature , dynamics and instrumentation, the notes to be played are shown in the form of notes that are read from left to right. The different tone durations are represented by different note forms ( note values ), the pitches are defined by the vertical position. Two staves represent the distance of a third ; the distance between a note lying between the lines and a note lying on one of the neighboring lines is one second . The clef at the beginning of each system defines a reference tone for a certain staff line, from which the other pitches can be derived: on the illustration the tone g ' on the second line from the bottom. In the picture you can not only read off the relative note spacing (third and second), but also deduce from the treble clef that the notes a'-c '' and a'-h 'are meant. For sounds that are too high or low, to find space on the lines are guides used.

In polyphonic pieces of music it is common to place several staves one below the other, each of which contains a voice , so that the simultaneous musical events are arranged one above the other. One then speaks of a score . Line systems for lower tones are usually given a bass clef, which, in contrast to the treble clef, marks the small f as the reference tone on the second line above.

A practical example

Using the following example of a simplified representation of the beginning of Johann Strauss ' classic "On the beautiful blue Danube" ( ), the basics of modern music notation can be explained well:

- At the top left is usually the tempo designation, often in Italian, here meaning "waltz tempo". Below or next to it, the more specific metronome can be specified in BPM ( beats per minute ) , here 142 quarter- beats per minute .

- The indication of the time signature defines the quarter as the basic beat of the melody: The three-quarter time has its focus at the beginning of the measure, the main beat is followed by two more beats before a new one

- Barline indicates the beginning of the next measure .

- Is left in the system of the touch key , in this case, the treble clef, indicating that the second lowest line the tone g ' represents. To the right are the

- Accidental sign : The two crosses on the lines of the f '' and c '' indicate that the two tones f and c are increased by a semitone in all octaves, i.e. should be played as f sharp and c sharp , from which u. a. with some probability D major or B minor result as possible keys of the waltz (in fact the key is D major, which only emerges from the consideration of the further harmonic and melodic progression, the general accidentals, strictly speaking, say nothing about the actual key). These accidentals apply to the entire system as long as they are not temporarily overwritten by other accidentals (up to the end of the measure) or (usually in connection with a double barline) replaced by other general accidentals. Clef and accidentals are noted again at the beginning of each staff.

- All previously listed factors should first be read and processed by the musician before he plays the first note: A quarter note on the note d ' , the dynamics (volume) of which is indicated by the mf ( Italian mezzo forte , medium loud, normal volume ) below . In this case, a barline follows immediately after the first note, before a full bar of three quarter beats has ended. The piece does not begin with the first stressed part, but with the unstressed third part of the bar, a prelude .

- The next quarter note (again d ' ) now sounds on the first beat of the next measure. She is through one

- Legato - or slur connected with the following notes f sharp ' and a' , which are not to be re- articulated , but to be played in conjunction with the previous one.

- In the next bar there is half a note a ' that lasts the first two beats and one

- Quarter note follows. At this point there are two noteheads on top of each other in the positions f sharp '' and a '' , which means that these two tones should sound at the same time. There is also a staccato point above that indicates a particularly short articulation. After playing this two-tone again at the beginning of the next measure, one follows

- Pause the length of a quarter of a beat. In the following prelude, the previous motif is repeated a third lower.

- Under the last three bars is a decrescendo fork that calls for the volume to be decreased; one could just as easily write “decresc.” or “dim.” ( diminuendo ) . As a rule, under the system in italics, those instructions are written that relate to the dynamics and the character of the performance, above the notes there is information about the tempo in bold letters, such as "accel." ( Accelerando ) or " a tempo ".

history

Ancient and non-European musical notation

There are many indications that in ancient Egypt since the 3rd millennium BC Chr. A kind of musical notation existed and other nations tried to arrest music writing.

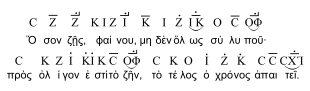

The first fully developed and now fully deciphered notation is the Greek, whose first appearance, according to various sources, was in the 7th century BC. BC or only around 250 BC Is to be dated. This musical notation used letters - possibly named after the strings of the kithara - for the pitch and marked the duration of the tone with symbols written over them . It has survived on many fragments , but there is only one composition that is completely preserved in this way through an inscription, the Seikilos epitaph , which was carved in a tombstone near Ephesus in the 2nd century AD .

In Europe, the Greek notation was lost with the fall of the Roman Empire ; its later decipherment was only possible with the help of Roman music-theoretical writings from the first centuries after Christianity. How quickly this tradition was forgotten, however, shows the following quote from the church father and Bishop Isidore of Seville from his Etymologiae (around 625), in which he claims that it is impossible to write down music:

“Nisi enim ab homine memoria teneantur, soni pereunt, quia scribi non possunt”

"Because if they are not remembered by people, the tones pass because they cannot be written down."

Outside of Europe, notation systems developed, especially in China , Japan and India , which often noted the melody in smaller characters next to or above the sung text, but left a lot of rhythmic freedom. Apart from that, tablature scripts were also used for instrumental compositions. The Arabic musical notation, which was in use from the 13th century , is rooted primarily in the Greek tradition that was still handed down there, but hardly developed any further, as the improvisational character of the music predominated.

In general, it can be said that, apart from the Greeks, for most of the peoples music notation served more as a memory aid for largely improvised music and less to preserve melodies for posterity. The more precise notation system also developed in Europe because the freer, improvised music faded into the background in favor of the ecclesiastical tradition of composed and ritually repeatable psalmods and chorales .

Neumes

In the middle of the 9th century , a new type of musical script for Gregorian chant developed in European monasteries , which used neumes as symbols that were notated over the text. They represented the visualization of the waving movements of the choirmaster or the singer ( Greek νεύμα neuma , German 'wink' ). Thus a single neume stood for a certain melodic phrase. However, different graphic symbols were used in different countries and monasteries. The oldest source of this notation can be found in the Musica disciplina by Aurelian von Réôme around 850. Earlier dated fragments of visigotic neumes from the Iberian Peninsula have not yet been deciphered. The Lambach missal shown opposite dates from the end of the 12th century , the original of which is in Melk Abbey .

Guido of Arezzo

Lines were gradually added to the lineless adiastematic new notation, initially two colored staves for the notes f and c to mark the semitone steps e – f and b – c . In order to also accurately record the tone steps between the lines, Guido von Arezzo added a third line between the f and c lines at the beginning of the 11th century . The third line system, with which every diatonic step can be precisely identified, was invented. Guido also recommended - depending on use - to put a fourth line above or below the three lines.

Instead of colors, Guido now used letters (c or f) at the beginning of a system to mark one of the halftone positions. With this Guido had also invented the clef . He mainly used a lowercase c to set the c ' . The f was used less often, but has stood the test of time as an F or bass clef.

Guido recognized in practical lessons that this now diastematic notation still contains a didactic weakness. Although the modal relationships of the tone steps remain relatively the same, they are named differently depending on the pitch. Therefore, Guido also invented the relative solmization , in which both the semitone step e – f and the semitone step h – c (later also a – b ) are sung with the same tone syllables “mi – fa”.

Guido's services are therefore didactically motivated. With the third line system, he visualized pitch steps exactly for the first time; he uses the relative solmization to functionally name the semitone steps so that students always articulate and sing them the same way; Finally, with the Guidonic hand , Guido includes the “understanding” hand in the learning process. This bundling of different stimuli is so effective that music pedagogues continue to use Guido's method - at least in didactic terms - to this day.

The point of solmization is not to replace the absolute notation, but simply to impress the relative relationships of the tones in the memory, similar to the way Arabic numerals are used to denote melodies (1 = always root), or Roman numerals to denote harmonies (I. = Tonic). The meaning and necessity of the diastematic notation is in no way called into question by these didactic measures.

In Guido's time and for a long time afterwards, four lines were usually enough, especially for singing. This was not only due to the small range of the chorales, but also to the flexible clefs. They made it possible to fit the range of a voice or a melody into the system of lines. The four-line neum system with the C key is still in use in church music today in conjunction with the neumes of the square notation . As in modern notation, auxiliary lines were and are used for particularly high or low notes . This type of notation with four continuous staves can still be found in choral books today .

For other purposes and different musical instruments systems with more or less lines were soon used. The modern five-line system originated in France in the 16th century , but other spellings were also used well into the 17th century . The C clef preferred by Guido has been replaced in many areas by the F and G clefs, which are practically only used in the form of a treble clef and bass clef.

Modal notation

In order to be able to specifically record the rhythm in the notation, the modal notation developed in Western Europe during the so-called Notre Dame epoch in the 12th century to the beginning of the 13th century . In contrast to the notation used today, this is not based on individual beats in the clock structure, but on six elementary rhythms (modes) that are based on Greek meter measures . Each mode is described by a ligature (group of 2–4 notes) in square notation .

Mensural notation

Since the modal notation only allowed a fixed number of different rhythms, the need for reform soon arose, especially for the writing of purely instrumental music. With the introduction of the (black) mensural notation in the 13th century ( Ars Nova ), the rhythm was also noticeable through the use of different note values . The note values at that time were called Maxima, Longa, Brevis, Semibrevis, Minima and Semiminima, their exact metric ratio depended on the scale used and the value of the neighboring note (s).

In the 15th century , the enlargement of the manuscripts made it too time-consuming to fill in the noteheads, too much precious ink was used, and the paper used was thinner and could tear more easily if it was too damp: the so-called white mensural notation was created. The blackening was only done to identify particularly small note values (see the opposite pages of a motet by Loyset Compère, probably composed in 1472 ).

Rhythm notation

In 1280 Franco von Köln developed the first precise rhythm notation, which found expression in complex works that, contrary to the usage at the time, were hostile to improvisation. It is based on the (perfect) three and (imperfect) two-way division of the note lengths. (They were related to the length of the brevis by bracketing them in dots.)

The Ars Nova was able to create complex (polyrhythmic) works with isoperiodic (tenor) and isorhythmic in the periods .

In the Franco-Flemish Renaissance, the complicated rhythm of the Ars Nova was simplified again to simpler proportions.

In addition, the rhythm in its basic pattern determined the form, to which a certain character was ascribed in dances, which were summarized and standardized in suites.

With the mensural notation, the rhythmically exact notation was consolidated (up to the early Romantic period (triplets and higher subdivisions), the more difficult the notation looks, the younger it is.) Quantz specified the initially imprecise punctuation in the Baroque to the term commonly used today (the three-part division ). For rhythmically demanding music e.g. B. Bruckner, innovations are general, the quintuplets, with Bartók the odd rhythms, or for, z. B. African music, it is still insufficient today, there are different notations of ambiguous facts, the binding nature of which is under discussion.

The modern time signature

In the 15th century also began staves to share with vertical lines, so-called Mensurenstriche, into sections. However, these parts were not bars in the modern sense, since the music of that time had very irregular patterns, but were used to indicate in scores where the different voices had to play or sing at the same time.

Towards the end of the 17th century , the modern rhythmic system with time signatures and bar lines was introduced, which took the smaller values of the white mensural notation with it as musical notation.

It can be seen from the history of modern notation that its development arose mainly from the requirements for sung music, and in fact one often hears that it is unsuitable for the writing of instrumental music. The numerous attempts in the last two centuries to reform the musical notation system have all failed, either because of the conservative attitude of the musicians or because the newly designed systems were less suitable than the old one. However, there are also alternative notations for certain specialist areas, some of which are based on ancient traditions.

The music notation from handwriting to computer printing

Copyists

The development of notation was similar to the history of the written word. After music texts chiseled in stone or scratched in clay, ink and paper soon developed into the ideal medium.

The more or less legible manuscripts of different composers can say a lot about their personality, just compare Johann Sebastian Bach's uniform and controlled handwriting (shown at the top) with the adjacent excerpt from Ludwig van Beethoven's E major Sonata op.109 . To this day, the deciphering of the autographs has been difficult expert work when it is necessary to distinguish whether a staccato dot or just an ink stain is present, or if - as is often the case with Franz Schubert - the graphic intermediate stages from accent wedge to diminuendo fork should be adequately reproduced at the time of printing.

When the composer had written the score of a new orchestral work, it was the job of the copyists to copy the parts of the individual instruments from it, which was a time-consuming work. If the piece was only completed at the last moment, it had to be done quickly, and from many contemporary testimonies we know descriptions of “still damp sheet music” from which the musicians played a world premiere .

Letterpress

After the introduction of letterpress printing , musicians began to experiment with this technique and printed from engraved or cut templates made of wood and metal. Later, the principle of movable type was also transferred to sheet music printing , as can be seen in the adjacent illustration from Palestrina's Missa Papae Marcelli . In 1498, the Venetian Ottaviano Petrucci invented sheet music printing with movable type; his invention made Venice the European center of sheet music printing for the next few decades. The publications of Pierre Attaingnant were of particular importance for the notation with movable, freely combinable types . For the first time, musical works were able to appear in large editions and made available to a broad public. The vast majority of the music, however, continued to be played from handwritten material.

Note engraving

In the 18th century , copperplate engraving became more and more widespread in France, and thanks to its outstanding quality it soon caught on in the major music publishers in Europe. The tricky job of the engraver consists in arranging the division of the systems and bars with all their additional labels and symbols on the sheet in such a way that the player can read an organically readable whole with suitable places to turn the pages, and this layout on the engraving plate ( lead - tin - antimony - alloy ) is inverted outline. The actual piercing process then takes place with a raster with which the five parallel staff lines are drawn at once, various steel stamps and other scratching and piercing tools. A used lithography stone serves as a base . Keys, accidentals, notes, small arcs, brackets and the entire script are stamped in with steel. Note stems, bars, small bar lines and larger arcs are engraved with steel engravers (corresponding to those from the copper engraving ). Crescendos and long bar lines across several systems are drawn with the so-called pull hook. Before the final print, a so-called green print (letterpress printing process ) is made for correction. During the correction, the incorrect spot is marked on the back of the engraving plate with the help of curved pliers. Then the lead of the defective area is driven up with the help of a nail point. After various smoothing and deburring processes, the correction can be carried out, i.e. the corresponding symbol can now be placed in the correct place. The creation of a sheet music page takes between 8 and 12 hours, depending on the content.

lithograph

Between 1796 and 1798, Alois Senefelder developed a flat printing process based on Solnhofen limestone , which was suitable for the quick and inexpensive reproduction of sheet music. The process later became known as lithography or stone printing and was adopted by many artists.

Static friction process

A special way of producing notes was that the engraver marked the corresponding note lines and the text on a cardboard box. This template was then set in the light method ( phototypesetting placed) on a film. Keys, notes, necks, etc. were then rubbed onto this film in the same way as the well-known adhesive letters. In terms of quality, this method was inferior to conventional engraving. The time required to produce a sheet of music was roughly equivalent to that of a sheet of music engraving, but the lead exposure of the engraver was eliminated. This procedure was used in the GDR since around 1978.

Musical notation machine

Around 1900, the Viennese Laurenz Kromar developed the so-called Kromarograph , an automatic musical notation device for recording improvisations on the piano. This development had been preceded by similar attempts since the 18th century, which, however, in contrast to Kromar's development, had not led to satisfactory results. "The Kromarograph not only fulfills its purpose for the quick, accurate recording of improvisations or compositions, but the electrical current used provides an exact picture of the game, verifiably and relentlessly records the correctness of the same as any error made."

Computer note set

The first experiments using computers for printing notes took place as early as the 1960s , and serious results have been around since the 1990s . In addition to closed-source music notation programs such as Finale , PriMus , Score , Sibelius or capella , which are increasingly replacing hand-engraved music even at renowned music publishers, there are also open-source solutions such as LilyPond , MuseScore , MusiXTeX or ABC and ABC Plus .

Programs such as Logic or Cubase are used in popular music today . These are elaborate sequencer programs, in which music printing functions have also been integrated, but which hardly ever meet professional requirements and make aesthetically convincing editions of popular music a rarity. However, these sequencer programs can help to reduce the effort required for some of the high-quality music notation with the typesetting programs listed above: MIDI files of recorded pieces can be exported that can be imported into typesetting programs; the score only needs to be adapted, not created from scratch.

It is usually found more pleasant to play from notes that have been handwritten or set by an experienced music composer. A particularly negative trend is felt that, for reasons of cost, publishers are increasingly issuing grades that have not been set by professional marketeers but by laypeople and therefore do not always meet high standards. This is often the case with popular or educational music, e.g. For example, the author of a school has set his work completely and submits it for printing with the finished layout.

Alternative notation systems

Tablature

Tablatures (fingerprints) were developed earlier than modern musical notation and were used for plucked , string and keyboard instruments , and more rarely for woodwind instruments . Lutenists and guitarists in particular retained the fingering until the end of the 18th century. Guitar tablatures came back into use in the 20th century.

The beginning of the song “All the little birds are already there” is shown on the right. Rhythm signs in tablatures for lute instruments (see historical lute tablatures ) do not denote individual note values, but the duration until the next note is played. In modern guitar tablature, however, the values of the individual notes can be designated (see modern guitar tablature ).

A special kind of tablature is the Klavarskribo , a notation for keyboard instruments that was developed by the Dutchman Cornelis Pot.

Tone names

In texts about music or in the absence of music paper, the notes of a melody are often described by their note names. Upper and lower case and hyphenation or indexing can be used to assign a clear octave designation to a tone . For the Blue Danube Waltz in the example above it could look like this: "3/4: d¹ | d 1 f sharp 1 a 1 | a¹ “ etc. Instead of f sharp , f ♯ can also be written, as well as a ♭ instead of a flat. Note, however, tone names in other languages , the ignorance of which can cause misunderstandings.

In digital text formats in particular, an alternative short notation has developed that, based on the 88-key standard keyboard , counts the octaves from bottom to top, starting with C. The contra-C ('C) is the first C on the keyboard, that's why it's called C1. The five-stroke c (c '' '' ') , the highest key, is the eighth C on the keyboard and is therefore called C8. The semitones are shown as raised regardless of their harmony connection with ♯ (see enharmonic confusion ), Gb '' would be written as F ♯ 5, for example .

This syntax is for example in Tracker - music programs used. The time axis runs vertically from top to bottom. The choice of the time increment is exclusively a matter of interpretation. Often a line corresponds to a 16th note, but with changes in tempo a complex structure like 30 percent swing can be achieved. The pitch is entered in the notation described. The compactness of this quasi one-dimensional notation enables a clear notation of further musical parameters such as length or volume, but also specific electronic processing options that influence the timbre.

Other ways of naming notes are relative and absolute solmization , which lead their note names back to Guido von Arezzo , and Carl Eitz's tone word method .

Digit notation

In many cultures, the score is mainly represented using numbers, letters, or indigenous characters that represent the sequence of notes. This is the case, for example, with Chinese music ( jianpu or gongche ), with Indian music (sargam) and in Indonesia (kepatihan) . These different systems are collectively referred to as numeric notation.

The number notation as used in jianpu should be given as an example . For example, the numbers 1 to 7 are assigned to the pitches of the major scale. For a piece in C major these are:

Note: C D E F G A H Solfege: do re mi fa sol la si Notation: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

The origin of this notation is the number notation according to Emilé Chevé .

Shape Notes

Shape Notes are a notation system that was developed in the United States at the beginning of the 19th century to make it easier for laypeople to sing from notes. Shape Note songs use the standard notation, but the noteheads also have characteristic shapes that are assigned to the levels of the scale and are named with solmization syllables .

The first Shape Note hymnbook was published in 1801 by William Smith and William Little: The Easy Instructor . With the Singing School movement , Shape Note hymn books became very popular in the United States.

Two systems of the shape-note notation have established themselves and are in use today: The 4-shape system with the solmization syllables Fa So La Mi , which is used in the hymn book The Sacred Harp , and the 7-shape system with the solmization syllables Do Re Mi Fa So La Ti / Si , the z. B. is used in the hymn book The Christian Harmony .

Notation codes

In order to be able to electronically "note" and save musical parameters, various notation codes were developed. A distinction must be made between codes for playing music such as MIDI , codes for entering or storing music for electronic notation (which in principle includes all file formats from music notation programs) and those for musicological analysis of music such as the humdrum code. MusicXML was conceived as an exchange format and combines elements from Humdrum, MuseData and MIDI. MEI is similar to MusicXML, but is based on TEI and takes more musicological requirements into account , especially with regard to the edition philology .

Abbreviations for chords

In the tradition of the figured bass , a bass part is provided with numbers from which the chord to be played above the bass note can be derived. Many composers also used the numbering to quickly sketch the harmonic course of a work. For example, when completing Mozart's Requiem , Franz Xaver Süssmayr was able to rely on a few figured basses that Mozart had notated himself. The figure on the right shows a simple figured bass, in the upper system a possible implementation of the numbering is written out.

The chord symbols used today, especially in jazz and popular music, follow a different direction , which, in addition to the note name of the chord root, have a code of letters and numbers that describe the type of harmony. This system, which works completely without staves, is used in conjunction with a melody notation system , but there are also collections in which only the text and chord symbols of a song are printed because the melody is assumed to be known.

Braille notation

Using the same characters as in his Braille , Louis Braille invented a musical notation for the visually impaired that is used worldwide today. In its ingenious system of note, octave, harmony and additional symbols it is possible to bring the vertical sequences of polyphonic music into a linear sequence of characters that the blind can read. The National Library for the Blind in Stockport ( UK ) has the largest collection of sheet music in Braille .

Graphic notation

In the 20th century , many composers wanted to break away from classical music, which they considered too unsuitable and too specific for their music. So they started experimenting with graphic notation to give more space to the inspiration and creativity of the performing musician. Important proponents are Karlheinz Stockhausen , John Cage , Morton Feldman , Roman Haubenstock-Ramati and Iannis Xenakis . George Crumb's “Makrokosmos” piano cycle is particularly well-known .

Color notation

Guido von Arezzo already used colors to illustrate the notation; these disappeared with the advent of music printing. A new attempt was made by Arno Peters . The Peters notation enables a spatial representation of the pitch and the duration of the tone. He assigned a color to each of the seven tones. When making the assignment, he observed a similar frequency relation within the light spectrum .

6-plus-6 notation

The notation developed by Johannes Beyreuther reflects the arrangement of the two rows of 6-plus-6 instruments . It consists of white and black notes. Notes of the same color are arranged in whole tones. Tones 1 to 3 of the diatonic scale have the same color, tones 4 to 7 the corresponding different color. A color change means a change in the row to be played. A big advantage is the transposition. A melody written in C major can be played on two-row 6-plus-6 instruments by shifting the starting note in five other keys, on three-row instruments even in all twelve keys. Even on instruments with a shifted 6-plus-6 arrangement such as the Hayden Duet concertina , the color of the notes indicates the row in which the keys are located.

There is no bass clef, so the bass notes are read in the same way as the melody notes.

Since there are no accidentals, there can be no mix-up of notes. This means that the 6-plus-6 notation is not only suitable for 6-plus-6 instruments, but also for hobby musicians with other instruments.

The 6-plus-6 notation is part of the Beyreuther musical principle .

Rhythm notation

The rhythm notation only provides information about the point in time at which sound events occur relative to the meter. You can z. They can be used, for example, in accompanying books for percussion guitar, where the rhythm notation dictates the percussion pattern to the instrumentalist, but not how he has to play which accompanying chord (since there are several options for e.g. A major). As in the picture, however, it may be that the rhythm notation ( English rhythm slashes because of the inclined shape of the noteheads) is also added chord names or even lexicon images, but this is not a matter of course.

Piano roll notation

A very simplified notation is usually used in sequencer programs for processing music with the computer. If, for example, pieces of music are recorded on a MIDI keyboard, the computer only receives information about which key was pressed at which point in time and when was released, similar to recording on a piano roll . Clef, key, time signature, accidentals and the exact note values are not available to the computer. A representation of the recorded data in the classical notation is therefore only possible with very complex algorithms and manual adjustments. For this reason, sequencer programs often work with piano roll notation ( piano roll notation), which is similar to the imprint on a piano roll and the representation of which can be programmed very easily. The piano roll notation also allows pieces of music to be entered or edited easily on the screen ( called the piano roll editor in some programs ). Piano roll notation can also be used to intuitively learn piano pieces without having to be able to read classical notes. Piano roll notations exist in numerous variants, some using color. In some countries, such as the USA, music notations can be patented. Among the patents are some examples of piano roll notation, such as U.S. Patent 6987220 (2006) for a piano roll-like notation with colors.

Klavarskribo

The notation system Klavarskribo ("keyboard writing") developed in 1931 is based on the structure of the piano keyboard. Klavarskribo is notated vertically from top to bottom. Groups of two or three lines each represent the black keys, the note symbols are arranged on or between these lines.

Sight reading

The term sight reading ( English sight-reading ) refers to the conversion of the listed composition to the specific instrument directly on the first reading of the notes without hassles or practice. The Italian name is a prima vista 'at first sight' . The musician must be able to read the music quickly so that he can play the composition immediately at the intended tempo. The same applies when singing , it is defined here as (from-) sight-singing called.

See also

literature

- Willi Apel : The notation of polyphonic music. Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 1962, ISBN 3-7330-0031-5 .

- Hans Hickmann, Walther Vetter, Maria Stöhr, Franz Zagiba, Walther Lipphardt, Luther Dittmer, Martin Ruhnke, Friedrich Wilhelm Riedel, Wolfgang Boetticher, Rudolf Stephan: Notation. In: Friedrich Blume (Hrsg.): The music in past and present (MGG). First edition, Volume 9 (Mel - Onslow). Bärenreiter / Metzler, Kassel et al. 1961, DNB 550439609 , Sp. 1595–1667 (= Digital Library Volume 60, pp. 55100–55259)

- Günter Brosche : Musicians' manuscripts. Reclam, Ditzingen 2002, ISBN 3-15-010501-3 .

- Gilles Cantagrel : Music manuscripts - music manuscripts from 10 centuries - from Guido von Arezzo to Karlheinz Stockhausen. Translated from the French by Egbert Baqué. Knesebeck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-89660-268-3 (color picture book).

- Max Chop : The development of our musical notation. In: Reclams Universum 28.2 (1912), pp. 1250-1254.

- Thrasybulos Georgiades : Music and Rhythm among the Greeks. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1958.

- Martin Gieseking: Code-based generation of interactive note graphics. epOs-Music, Osnabrück 2001, ISBN 978-3-923486-30-4 .

- Elaine Gould: Head over heels. The notation manual. Translated from the English by Arne Muus and Jens Berger. Faber / Peters, London / Leipzig 2014, ISBN 978-1-84367-048-3 .

- Andreas Jaschinski (Ed.): Notation (MGG Prisma). Bärenreiter, Kassel u. a. 2001, ISBN 3-7618-1625-1 .

- Erhard Karkoschka: The typeface of new music. Hermann Moeck, Celle 1966, ISBN 3-87549-002-9 .

- Hartmut Möller u. a .: notation. In: Ludwig Finscher (Hrsg.): The music in past and present . Second edition, factual part, Volume 7 (Myanmar Sources). Bärenreiter / Metzler, Kassel et al. 1997, ISBN 3-7618-1108-X ( online edition , subscription required for full access)

- Rainer Nonnenmann: Invention through notation - on the production of musical thoughts while writing. In: Neue Zeitschrift für Musik , 169th year 2008, issue 5, pp. 20-25.

- Egon Sarabèr: The Art of Reading Notes . For beginners and advanced. 2nd, improved edition. Papierflieger Verlag, Clausthal-Zellerfeld 2018, ISBN 978-3-86948-626-0 .

- Manfred Hermann Schmid : Notation Studies: Writing and Composition 900 - 1900 . Bärenreiter, Kassel 2012, ISBN 978-3-7618-2236-4 .

- Karlheinz Stockhausen : Music and Graphics. In: Darmstadt Contributions to New Music III. Schott, Mainz 1960.

- Albert C. Vinci: The musical notation. Basics of traditional music notation. Bärenreiter, Kassel 1988, ISBN 3-7618-0900-X .

- Helene Wanske: music notation. From the syntax of the note engraving to the EDP-controlled notation. Schott, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-7957-2886-X .

- LK Weber: The ABC of music theory. 13th edition. Zimmermann, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-921729-02-5 .

- Rudolf Witten: The theory of printing music notes . Ed .: Bildungsverband Deutsche Buchdrucker. Leipzig 1925.

- Wieland Ziegenrücker: ABC music. General music theory. 6th, revised and expanded edition. Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-7651-0309-4 , pp. 23-48 ( From the notes ).

Web links

- Essay on absolute and relative notation ( Memento from September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 44 kB)

- Magnificent images from the Vatican's music collection (English)

- Learn grades in four steps in the online course with a subsequent online test

- Learn to read sheet music - online tutorial on musikanalyse.net

- Synopsis of Musical Notation Encyclopedias - tabular index of individual questions in the standard works by Gould, Vinci, Wanske, Stone and Read (English)

- To the story . schott-international.com

- Boris Fuchs: The history of music sheet printing technology - an overview . ( MS Word ; 66 kB) August 23, 2012.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Johannes Wolf: Handbuch der Notationskunde . Part II, Leipzig 1919, p. 458.

- ^ Rudolf Kaiser: Demonstration of the radiation keyboard and the Kromarograph. In: Gustav Mayer (Ed.): Report on the 1st Austrian Music Pedagogical Congress. Vienna / Leipzig 1911, pp. 175–178.

- ^ Adalbert Quadt : Lute music from the Renaissance. According to tablature ed. by Adalbert Quadt. Volume 1 ff. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1967 ff .; 4th edition, ibid. 1968, Volume 2, Preface (1967).

- ^ Adam Tee: A Formal Grammar for Describing Music. (No longer available online.) February 15, 2001, archived from the original on May 15, 2008 ; accessed on March 9, 2013 .

- ^ The Humdrum Toolkit: Software for Music Research. In: humdrum.org. Retrieved January 15, 2018 .

- ↑ Arno Peters: The true-to-scale representation of the tone duration as the basis of octave-analog color notation. Academic Publishing House , Vaduz 1985, OCLC 216675474 .

- ↑ Website of the Beyreuther Musikprinzip

- ↑ Johannes Beyreuther : Making music without obstacles - The new way to music. Kolbermoor 1985.