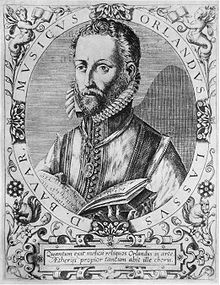

Orlando di Lasso

Orlando di Lasso (French: Roland or Orlande de Lassus; * 1532 in Mons , Hainaut , † June 14, 1594 in Munich ) was the most famous composer and conductor of the Renaissance during his lifetime .

Live and act

The birthplace of Orlando di Lasso is undisputed; His year of birth is not entirely certain. Because members of the upper class knew their date of birth exactly, music historians conclude that the composer came from a humble background. He himself usually gave 1532 as his year of birth, but even during his lifetime there were contradicting information here, so that 1530 or 1531 are also possible. He received his first lessons in reading, writing and singing in his hometown, where he worked as a choirboy at the church of Saint-Nicolas-en-Bertaimont until he was 13 years old. At that time, recruiters for the nobility looked all over Europe, especially in the so-called Spanish Netherlands, for beautiful boy's voices. The first biographer of Lasso, Samuel von Quickelberg , reports that Orlando was kidnapped twice because of his "bright, lovely voice" and brought back by his parents. In the autumn of 1544 he left his hometown in the service of Ferrante I Gonzaga , viceroy of Sicily and general of Emperor Charles V. Ferrante was on a journey through the Netherlands after the peace treaty of Crépy on September 14, 1544 and initially traveled with Orlando via Fontainebleau to Mantua and Genoa and finally to Palermo in Sicily, where they arrived on November 1, 1545. Here Orlando gained access to the circles of the local nobility. On this and the following trips through Italy, he also got to know the folk music there and the improvisation of the Commedia dell'Arte , which inspired him to make his first attempts at composition.

In June of the following year he traveled to Milan with Ferrante Gonzaga ; there his employer was appointed governor and commander of the imperial garrison. Here Orlando made the acquaintance of the composer Bartolomeo Torresano (around 1510–1569). There is some evidence that a teacher-student relationship developed between the two; Music historians suspect that Torresano may be the author of the madrigal "Non vi vieto", which was initially attributed to Orlando di Lasso. In January 1549 Ferrante Gonzaga entrusted the young Lasso, whose voice had broken, to the loyal knight Costantino Castrioto, with whom he went to Naples , where he worked as a musician for about three years with Giovanni Battista d'Azzia, the Marchese di Laterza , stayed. The latter was a brother-in-law of Ferrante and an amateur poet; Orlando set one of his sonnets , "Euro gentil", to music. In his service, Orlando made extensive acquaintance with the social life of the upper class there, with the humanistic ideal of the fully educated person, where theater performances with musical accompaniment were practiced in circles, as well as with the improvisations of Naples' street musicians and its street theaters. All of this had a lively influence on Orlando's personality development and compositions. In addition, he acquired extensive knowledge of literature and was soon fluent in German, Italian, French and Latin.

At just under 20, between December 1551 and May 1552, Orlando was in the service of Antonio Altoviti , Archbishop of Florence , who had fled to Rome as a result of a family feud . It is not known what function the young composer held for him. Music historians consider it possible that Ferrante had deliberately sent his protégé Orlando to this Francophile dignitary in order to obtain information about his political intentions. Altoviti was a music connoisseur and supported the composer Giovanni Animuccia (around 1514–1571), who spoke of a "new music" in a dedication in 1552, alluding to the current controversy over tone sexes between Nicola Vicentino and Vicente Lusitano since June 1551 in Rome. Orlando probably got to know these new tendencies at that time and later referred to them in his first Antwerp print in 1555. Between May 1552 and March 1553 he could have been in Rome in circles of Neapolitan exiles, followers of the Prince of Salerno , Fernando Sanseverino, who was loyal to France , and arch enemy Ferrante Gonzaga, who sought to liberate Naples from the rule of Spain. One of the most famous composers of Neapolitan songs, Giovanni Domenico da Nola , was one of these exiles ; In a Roman edition of largely anonymous such Villanelles from 1555, Orlando di Lasso is mentioned by name in the title.

With Sanseverino's flight to the French court in March 1553, Orlando's employment at the Roman Lateran basilica coincides, the second most important church in Rome after St. The achievement of such a prestigious position by such a young musician can actually only be explained by the support of high-ranking people, for example Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga , the brother of Ferrantes, who maintained a close relationship with the cathedral chapter of the Lateran Basilica. Music historians assume that Orlando made contact with Palestrina there and maintained it well into old age.

Around June 1554, the composer resigned his position and left Rome to travel back to the Netherlands because of the illness of his parents, who had already died upon his arrival. He then traveled again with the singer, diplomat and adventurer Giulio Cesare Brancaccio (around 1515 - around 1585), a friend from Naples, and came to England at a politically important moment when the wedding of Philip , son of Charles V, with Maria Tudor was imminent. His companion was suspected of being a supporter of the French and was expelled from the country; Orlando returned to his homeland and settled in Antwerp for two years.

As a trading metropolis, Antwerp was an excellent place to promote the international career of a Dutch composer because of the wide range of contact options and the local publishers Tielman Susato and Jean Laet , who were able to publish his works. The collection of madrigals, villanelles, chansons and motets from Orlando, known as “Opus 1”, was published in two versions by Susato in 1555: once as the 14th and last part of a chanson series (since 1543) and shortly afterwards with an Italian title and a dedication to Stefano Gentile, a prominent Genoese in Antwerp. His “Antwerp Motet Book”, printed in 1556 by the publisher Laet, is also written in Italian and dedicated to Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle, an influential politician and minister of Charles V and Philip II of Spain. Orlando apparently sought employment in Italy or Spain with the help of prominent personalities, but was unsuccessful.

After all, through the mediation of Granvelle and Johann Jakob Fugger, who traded in Antwerp, he was hired as tenor singer to the court of Duke Albrecht V in Munich in September 1556 . There he received an extraordinarily high salary, which suggests that from the beginning he worked temporarily as Kapellmeister alongside Ludwig Daser . In the meantime he had a thorough knowledge of almost all genres of vocal polyphony, especially the motet. Its first publication by Susato shows that he was expressly inspired by “new models” from Italy and added the chromatic motet “Calami sonum ferentes” by Cipriano de Rore to this collection as the last composition .

In 1558 the composer married Regina Wäckinger, the daughter of a Landshut court chancellor who was also a servant of Duke Albrecht's wife Anna. Their marriage was very happy, also because the down-to-earth and practical Regina was able to create a balance to the spirited nature of Orlando. The exact number of their children is not known; three daughters and five sons are documented in writing; the latter all became musicians.

At that time, the Munich court orchestra played the church music for the Duke's daily mass and was also responsible for the official festival music, private chamber music and tribute music at state receptions; she also accompanied the duke on his travels. In 1550 it comprised 19 musicians, and in 1569 it had 63 musicians. Orlando's duties included a. Travels through Europe to recruit new musicians, teaching the choirboys, some of whom even lived with his family, rehearsing with the musicians and composing numerous new works. The correspondence between Orlando and Granvelle shows that the composer did not feel very comfortable there in his first years in Munich and even considered looking for another job. This was possibly due to his working conditions under Albrecht V, who demanded extensive and prestigious compositions from him, but did not allow him to have them printed because he regarded them as the exclusive property of the Bavarian court and wanted to reserve them for performances for private use - thus the Prophetiae sibyllarum , the Sacrae lectiones ex propheta Job and especially the Septem psalmi poenitentiales , all probably written from 1556 to 1559. The last-mentioned penitential psalms stand out due to a magnificent manuscript decorated with miniatures by the court painter Hans Mielich (1516–1573) and were created between 1563 and 1570. In the early 1560s, Orlando's relationship with his employer seemed to have improved, especially since he was 1563 had been promoted to Kapellmeister in place of the sick Ludwig Daser; In the previous year he had already led the band on Albrecht's trip to Prague and Frankfurt for the coronation of Maximilian II as King of Bohemia and German Emperor. Also in 1562, Orlando's most successful collection of motets was published by Berg and Neuber in Nuremberg , which received thirteen further reprints by 1586.

In the meantime, the composer's madrigals were also very successful in Italy, and the first French chansons appeared in 1559 with Adrian Le Roy in Paris and in 1560 with Pierre Phalèse in Leuven . His real international breakthrough with chansons and motets began in 1564/1565 when the editions of these genres were published by Le Roy and Ballard in Paris, by Phalèse in Leuven and by Scotto and Gardano in Venice . The year 1567 marked the temporary end of his madrigal work after the publication of the fourth book of five-part madrigals, dedicated to Alfonso II d'Este of Ferrara . From then on, the genres Magnificat and German song came to the fore. Hereditary Prince Wilhelm of Bavaria had married Renata of Lorraine in Munich in 1568 and set up his own court in Landshut; the composer dedicated his first collection of German songs to him in the same year. This wedding represented a high point in the work of the court orchestra under Orlando di Lasso, at which the composer himself appeared as actor, singer and lute player on the occasion of a Commedia dell'Arte . Due to his steadily growing fame as a composer, many European printers saw themselves induced to publish extensive reprints; in Munich this happened from 1569 onwards with the motet edition by Adam Berg in his twelve volumes of the Patrocinium musices . The Huguenots also adopted compositions from Orlando in the form of sacred counterfactures of his chansons. In 1570 he was raised to the hereditary nobility by Emperor Maximilian II. Orlando won the Évreux composers' competition twice - in 1575 and 1583 - each for the best Latin motet.

As a result of the composer's numerous contacts with other European courts, especially Charles IX. from France through the mediation of the publisher Adrien Le Roy, there were temporary fears in Munich that he might leave the court. However, Orlando had already turned down the offer of the French king to enter his service in 1574, although he had been receiving an honorary pension from him since 1560. After Albrecht V's death in 1579, the composer received an offer from Elector August von Sachsen in 1580 to come as Kapellmeister to his court in Dresden . Denominational considerations aside, Orlando's rejection was based on his comfortable financial situation in Munich and possibly also on his advanced age. In the previous ten years he had already developed an excellent relationship with Albrecht's successor Wilhelm; From 1573 onwards, he was responsible for the publication of an impressive series of large-format choir books with Orlando's masses , offices, readings and magnificats in the aforementioned Patrocinium musices . In 1581 the composer accompanied his new employer Wilhelm on a pilgrimage to Altötting .

After the influence of the Jesuits in Bavaria, particularly through Petrus Canisius , increased in the 1570s, the religious attitude of Albrecht and his son Wilhelm had also become stricter; with the latter this led u. a. to a fervent devotion to Mary. Already under Duke Albrecht in his later years the court chapel was saved and the staffing was reduced. This continued under Wilhelm, and even Orlando's salary was cut temporarily. The composer also followed the new religious tendency: the composition of secular works declined more and more, with the madrigals, on the other hand, there was a shift to the madrigals spirituale , and an increased religious tendency can also be seen in the collections of German songs (1583 and 1590). The three-part movements of the first 50 psalms in the German version by Caspar Ulenberg , published in 1588 and edited by the composer together with his son Rudolph, testify to a strictly counter-Reformation attitude.

Orlando di Lasso fell seriously ill in 1591, presumably a stroke , but recovered and was able to resume his work as a conductor, despite an offer from his employer to retire, probably because of an associated cut in salary. He also took part in the Reichstag well into old age . In 1592 Wilhelms Hofkapelle was reduced to 17 musicians due to the increasing expenses for the construction of the Michaelskirche . In 1594 even the composer himself was on the list of those to be dismissed. On May 24th, 1594, he had dedicated his work Lagrimae di San Pietro (The Tears of Penance of St. Peter) to Pope Clement VIII and died on June 14th of the same year. He left his widow Regina and his children; two of his sons, Ferdinand and Rudolph, were members of the court orchestra and also distinguished themselves as composers. His daughter Regina married the painter Hans von Aachen . Orlando's grave inscription in the cemetery of the Church of St. Salvator in Munich, which was closed in 1789, read:

- I sang discant as a child

- As a boy I dedicate myself to the old

- The man succeeded in the tenor

- In the depths now the voice dies away.

- May the Lord God praise us, wanderer

- Dull bass be my tone,

- The soul above with him!

The epitaph Orlando di Lassos is kept in the Bavarian National Museum in Munich.

meaning

Orlando di Lasso was undoubtedly one of the most famous composers of the 16th century, whose extraordinarily varied oeuvre quickly spread across Central, Western and Southern Europe thanks to the flourishing musical pressure. Between 1555 and 1594, on average, one edition of Orlando's works came out every month, as individual prints or collections ( anthologies ), be they reprints or new works, a number with which he surpassed all fellow musicians. The music publishers in Germany, France, Italy and the Netherlands virtually competed in marketing new or already published works by the composer. His success can also be seen in the unusually large number of instrumental arrangements of his compositions and the many, mainly spiritual counterfactures, especially of his chansons in France, England and Germany. Orlando maintained good contacts with many secular rulers in Europe, such as Charles IX. from France, to the own employers of the Bavarian House of Wittelsbach , Count Eitel Friedrich von Hohenzollern-Hechingen , Duke Alfonso II. d'Este in Ferrara, to the first minister of Emperor Charles V, to the Nuremberg Senate and to members of the Fugger banking family from Augsburg ; in the spiritual realm this included Popes Gregory XIII. and Clemens VIII, the bishops of Augsburg, Würzburg and Bamberg as well as the abbots of Benediktbeuern , St. Emmeram in Regensburg, Weingarten , Weihenstephan and Ottobeuren . Most of these personalities were also dedicators to his works. In addition, numerous music theorists of his time highlighted Orlando's oeuvre as a model for imitation. Orlando's motet collections also acted as a stimulus for a number of composers of his time to bring out their own collections of this type ( Alexander Utendal , Ivo de Vento ), or served as a preferred template for their arrangements (outstanding example: Jean de Castro ). In the genre of the parody mass there are at least 80 masses by other composers that go back to a model by Orlando di Lasso.

Orlando was a highly educated Renaissance man and a marked cosmopolitan of the 16th century, whose correspondence shows that he was not afraid to express his opinion freely. He knew how to skillfully use his intellectual superiority against the lack of understanding of his Bavarian employers. He combined the highest compositional mastery with enormous creative power, which, through him and Palestrina, came to the final climax of Franco-Flemish music. He showed a creative universality like no other and composed German songs, French chansons, liturgical music such as masses, magnificats and hymns as well as works for secular representation. One of the earliest comments on the characteristics of his music was a statement by his biographer Samuel von Quickelberg about his penitential psalms, in which he describes Orlando's extraordinary ability to translate texts into sounds in an illustrative and emotional way, with which he achieved an expressiveness that was unmatched in his time was. Based on the imitative counterpoint of the previous generation of composers, he abandons the strict imitation and composes a striking “contrasting style” in which the musical fabric changes from section to section in the service of the text. The editor Adrian Le Roy characterizes Orlando's musical language as "concise without many repetitions (in contrast to Jacobus Clemens non Papa or Nicolas Gombert ), well-worded and worked out down to the smallest detail, leaving out all unnecessary accessories".

The composer's unparalleled versatility is particularly evident in his overwhelming motet oeuvre, over 500 one-part and multi-part works for two to twelve voices, crowned by the posthumous edition Magnum opus musicum from 1604 by one of his sons. In this group of works, apart from the great variability in length and scoring, the strong textual and stylistic differences are striking. In the religious motets, the psalm settings have the greatest weight; in addition, the book of Job , the Proverbs and the Song of Solomon and from the New Testament mainly the four Gospels served as a basis. Secular motets, such as commissioned, homage and state motets with neo-Latin verses, wedding compositions , humorous motets and drinking songs also have great weight ; there are also didactic motets for two and three parts for the sons of Duke Albrecht and choirs for the Jesuit theater, such as the series of six works for the drama "Christ Iudex" by the Italian Jesuit Stefano Tucci . Orlando shows himself to be unsurpassed in his mastery of the "sound direction" when, in his five- and six-part works, with unlimited imagination, mostly in the service of the text, he allows various groupings of voices to follow one another, with the predominantly syllabic passages from the Nuremberg Motet Book of 1562 being perfect dosed, text-determined melismatics is used. The composer uses rhythm and syncopation in a versatile and textual manner as well as with the use of harmonies , where he makes lively and efficient use of dissonances , cross-positions and alterations . Orlando's motets are mostly freely composed, but still reveal a thorough knowledge of traditional techniques such as cantus firmus , ostinato , Soggetto cavato and canon or a combination of several of these techniques; Such suggestions can be traced back to role models such as Josquin Desprez , Adrian Willaert , Cipriano de Rore, Jacobus Clemens non Papa and Ludwig Senfl . Lasso's pupils were among others Giovanni Gabrieli (between 1575 and 1579), Antonius Gosswin and Leonhard Lechner .

Two genres are at the center of Lasso's liturgical work: the Mass Ordinarium and the Magnificat. There are 60 masses of his with confirmed authorship and 15 others where this is not guaranteed. The most extensive edition of masses was that of Le Roy and Ballard in 1577 with 18 works; The posthumous editions Paris 1607 and Munich 1610 are also striking, as is a considerable number of around 20 handwritten masses that were never printed. The last historical print of a mass was the short Missa Iager (Missa venatorum), published by Christophe Ballard in Paris in 1687. The absolute highlight was the parody mass under Orlando di Lasso, both in terms of the variety of templates and the compositional technique. The majority of the models are based on his own (15) and other motets ( Jachet de Mantua and Ludwig Daser) as well as on madrigals by himself and by others (Cipriano de Rore, Jacobus Arcadelt , Sebastiano Festa , Adrian Willaert and Palestrina). Claudin de Sermisy , Pierre Certon and Jacobus Clemens non Papa are among the chansons as templates . The enormous diversity of Lasso's mass works ranges from short, predominantly homophonic compositions to extensive contrapuntal cycles. His parody technique, which has been varied again and again, changes from literal quotation and limited processing to extensive reinterpretation of the original, so that his masses can be considered a true compendium of parody technique in the second half of the 16th century. He knew in an inimitable way how to follow a model and transform it at the same time. His enormous output of 102 Magnificat settings and twelve Marian Litania Lauretana results from the introduction of the liturgical reforms ( Usus romanus ) at the ducal Bavarian court since around 1580. Orlando's contribution to this genre is considered unique, not only because of its size, but also because He systematically applied the parody principle to the composition of Magnificats for the first time. “The diversity in the choice of models, namely madrigals (Cipriano de Rore), motets (Josquin Desprez) and chansons (Claudin de Sermisy) is so overwhelming that his group of parody magnificats, as well as his parody masses, provide an ideal cross-section of all possible styles of the 16th century ".

The composer also played a pioneering role in the history of the madrigal at the end of the 16th century, as he was the first in the Netherlands to publish madrigals and villanelles. The earliest five-part editions of this genre (Venice 1555 and Rome 1557) were reprinted more than ten times by several Italian publishers such as Scotto, Barré, Gardano, Rampazetto and Merulo as early as 1586. Later this popularity and also the number of such works decreased until he took up this type again in his last years and led to his coronation with his Lagrime di San Pietro . This later period from 1583 differed significantly from the earlier one, especially in the choice of texts, although still often based on texts by Petrarch , but more with a religious influence, then also on texts by Gabriele Fiamma (1533–1585) and Luigi Tansillo ( 1510–1568), the Lagrime lyricist . The latter seven-part work is a monumental, modally connected cycle in 21 parts in which the syllabic declamation predominates and in which melodic lines, rhythm and harmony are also determined by the text, with melismatic passages also occurring. Thus, these pieces show very illustratively the synthetic approach of the composer, in which the Roman and the Venetian madrigal types are merged, as well as the inexhaustible versatility of the composer, with an unsurpassed expressiveness as in the motets and highest economy as well as exemplary scarcity in his means. The late madrigals by Orlando di Lasso can be seen as a brilliant synthesis of the “classical achievements” of their genre, which show no tendency towards extravagance or obscuring the rules.

Orlando di Lasso was also the most highly respected composer of French chansons of his time, especially in France and the Netherlands, of course, where most of the editions were published. The impressive number of reprints up to 1619 shows the special and lasting demand for the composer's chansons as well as his particular popularity with the instrumentalists, as is evident mainly from the number of lute tablatures , but also among the Huguenots in France and England, where there are many counterfactors Chansons emerged. The variety of the selected texts corresponds to the variety of musical styles typical of Lasso, whereby three tendencies can be distinguished: the Dutch tradition of imitative counterpoint according to Nicolas Gombert and Clemens non Papa, the declamatory rhythm according to Clément Janequin and Claudin de Sermisy and the am Madrigal oriented style by Cipriano de Rore. The pieces of the madrigalistic chanson are considered to be particularly outstanding here, and the four eight-part, double chansons in dialogue form are particularly unusual. Overall, it becomes clear that Orlando di Lasso was the most internationally oriented composer in the field of French chanson.

The German songs of Orlandos represent a more regional genre, with which he followed the tradition of Ludwig Senfl. In contrast to the previous form, he initially made the five-part form the dominant norm, but later also used the four-part form and here, too, shows his legendary versatility in text selection and scoring. As with the madrigals and chansons, there is a tendency towards religious themes in his later German songs, including the monumental twelve-part “Die gnad kombt hier”. The first 50 psalms, composed alternately by Orlando and his son Rudolph, also belong to this group. The composer took numerous texts from Ludwig Senfl and the anthology by Georg Forster , but no polyphonic models. In contrast to the earlier German songs, these were no tenor songs , but were more based on the French chanson, occasionally also on the madrigal or the villanella; only in a few songs is the traditional tradition of the cantus firmus clearly visible. In the sacred songs, on the other hand, the main melody is consistently in the tenor, and the other voices accompany it in an imitative-paraphrase; this can be seen as a noticeable contribution from Orlando to the German chorale motet . He also knew Jakob Regnart's Villanelles and adopted a refrain from him in his work Die gnad kombt above . The great success of the German songwriting of Orlando di Lasso also results from the numerous reprints of these pieces by Adam Berg in Munich and Clara Gerlach in Nuremberg, during his lifetime and afterwards.

Works (summary)

Complete editions: Orlando di Lasso, Complete Works , 21 volumes, edited by Franz Xaver Haberl / Adolf Sandberger, Leipzig [1894–1926], reprint New York 1973; second edition, revised according to the sources, volumes 2, 4, 6, 12, 14, 16, 18 and 20, edited by Horst Leuchtmann, Wiesbaden 1968 and following

- Spiritual works

- 60 masses with guaranteed authorship and 15 more

- over 500 motets

- 102 Magnificat sentences

- 23 Marian antiphons

- 4 passions after an evangelist each

- Music for the Holy Week liturgy, including Lamentationes Ieremiae

- Lagrimae di San Pietro

- 32 Latin hymns

- 6 Nunc dimittis settings

- Sacrae lectiones ex Propheta Job

- Responsories

- Falsibordoni

- spiritual madrigals

- Secular works

- about 110 madrigals and related genres such as Morescen, Todescen, Villanelles and Canzonettes

- 146 French chansons

- about 90 German songs

- Prophetiae Sibyllarum (prophecies of the twelve visionaries), Musica reservata for Duke Albrecht V.

Many works have also survived in tablature; numerous compositions also appeared as sacred counterfactures in the Huguenot music collections, especially with Simon Goulard. The tradition of Orlando di Lasso's works for the period from 1555 to 1629 includes more than 120 different individual prints (some in several editions and reprints), including many collective prints and manuscripts.

See also

literature

- Henri Florent Delmotte: Biographical note on Roland de Lattre, known under the name: Orlando de Lassus , Gustav Crantz, Wiesbaden 1837

- Wilhelm Bäumker : Lasso, Orlando di. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biografie (ADB), Volume 18, Duncker and Humblot, Leipzig 1883, pages 1-9

- Wolfgang Boetticher : Orlandi di Lasso and his time 1532–1594. 2 volumes: monograph and list of works. 1958ff.

- Horst Leuchtmann : Orlando di Lasso. His life. Attempt to take stock of the biographical details , Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden 1976, ISBN 3-7651-0118-4

- Horst-Willi Gross: Tonal structure and tonal relationship in masses and Latin motets Orlando di Lassos , Schneider, Tutzing 1977, ISBN 3-7952-0223-X

- Horst Leuchtmann: Orlando di Lasso. Letters , Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden 1977, ISBN 3-7651-0119-2

- Massimo Troiano : The Munich princely wedding of 1568 , published by Horst Leuchtmann, Katzbichler, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-87397-503-3

- Horst Leuchtmann: Lasso, Orlando di. In: Neue Deutsche Biografie (NDB), Volume 13, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1982, ISBN 3-428-00194-X , pages 676-678 (digitized version)

- Franzpeter Messmer: Orlando di Lasso. A life in the Renaissance. Music between the Middle Ages and the Modern Era, Flade, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-922804-04-7

- Hans-Josef Olszewsky: LASSO, Orlando di. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL), Volume 6, Bautz, Herzberg 1993, ISBN 3-88309-044-1 , column 1205-1211

- Ignace Bossuyt: Art. Lassus . In: The music in the past and present (MGG). 2nd edition, personal section, volume 10: Kemp - Lert , Bärenreiter and Metzler, Kassel and Basel 2003, ISBN 3-7618-1120-9 , Sp. 1244-1306.

- Annie Coeurdevey: Roland de Lassus . Fayard, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-213-61548-9

- Johannes Glötzner: "Just being foolish is my style": Orlando di Lasso Pantalone , Edition Enhuber, Munich 2008, ISBN 3-936431-15-9

- Bernhold Schmid: Orlando di Lasso. In: Katharina Weigand (editor), Great figures in Bavarian history . Herbert Utz, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-8316-0949-9

- Jean-Paul C. Montagnier , The Polyphonic Mass in France, 1600–1780: The Evidence of the Printed Choirbooks, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Web links

- Works by and about Orlando di Lasso in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Orlando di Lasso in the German Digital Library

- Sheet music in the public domain by Orlando di Lasso in the Choral Public Domain Library - ChoralWiki (English)

- Sheet music and audio files by Orlando di Lasso in the International Music Score Library Project

- Cantore Archive Motets Sheet Music (PDF)

- Cipoo.net motets a. Madrigals sheet music (PDF + Midi)

- Free recordings by Umeå Akademiska Kör (ensemble) (in English / Swedish)

- Database of the Orlando di Lasso manuscripts

- Magnificent Codex of the Psalms of Penance Orlando di Lassos BSB Mus.ms. AI

- Song manuscript with mass chants by Orlando di Lasso in the culture portal bavarikon

- Orlando di Lasso in the Bavarian Musicians' Lexicon Online (BMLO)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Ignace Bossuyt: Lassus. In: Ludwig Finscher (Hrsg.): The music in past and present . Second edition, personal section, volume 10 (Kemp - Lert). Bärenreiter / Metzler, Kassel et al. 2003, ISBN 3-7618-1120-9 , Sp. 1244–1306 ( online edition , subscription required for full access)

- ↑ Marc Honegger, Günther Massenkeil (ed.): The great lexicon of music. Volume 5: Köth - Mystical Chord. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau a. a. 1981, ISBN 3-451-18055-3 .

- ↑ Horst Leuchtmann (editor): Massimo Troiano: Die Münchener Fürstenhochzeit of 1568. Discussions about the festivities at the wedding of the Bavarian Duke Wilhelm V with Renata of Lothringen in Munich in February 1568 , edited in facsimile, translated into German, with afterword, Notes and registers, Munich / Salzburg 1980, ISBN 3-87397-503-3 , page 124 (263)

- ↑ Linda Maria Koldau : Women - Music - Culture. A manual on the German-speaking area of the early modern period , Böhlau: Wien 2005, ISBN 978-3-412-24505-4 , page 159, note 186

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lasso, Orlando di |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Lassus, Orlande de (maiden name); Lassus, Orlandus (Latinized name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Franco-Flemish composer and bandmaster of the Renaissance |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1532 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Mons , Belgium |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 14, 1594 |

| Place of death | Munich |