Peace of Westphalia

The Westphalian Peace or Peace Agreement of Westphalia was a series of peace treaties that were concluded between May 15 and October 24, 1648 in Münster and Osnabrück . They ended the Thirty Years War in Germany and the Eighty Years War of Independence in the Netherlands.

Two complementary peace treaties were negotiated according to the separate venues for the peace congress according to the negotiating parties. For the emperor and France this was the Munster peace treaty ( Instrumentum Pacis Monasteriensis , IPM ) and for emperor and empire on the one hand and Sweden on the other hand the Osnabrück peace treaty ( Instrumentum Pacis Osnabrugensis , IPO ). Both contracts were finally signed on the same day, October 24, 1648, in Münster in the name of Emperor Ferdinand III. and King Louis XIV of France and Queen Christina of Sweden , respectively .

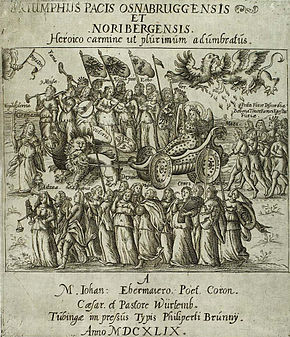

This was preceded by a five-year peace congress of all warring parties , which met at the same time in both cities. It was the first international congress at which almost all of the major European powers were represented. The Peace of Westphalia essentially fixed the end of fighting and important basic decisions, so in today's understanding of politics it was primarily a ceasefire agreement. However, the peace-making parties undertook to negotiate the details of a contractual peace order in a separate peace enforcement congress. These negotiations, which then lasted again for over a year, took place in Nuremberg beginning the following year - between April 1649 and July 1650 ( Nuremberg Execution Day ). The results of these negotiations were summarized in two recesses : on the one hand in the so-called interim recess, which was decided in September 1649, and on the other hand as a conclusion in the imperial peace recess of July 1650. The recesses contained binding agreements on disarmament and questions of compensation, they can be seen as a real peace treaty in the present sense, since they aimed at creating a stable new peace order. The recesses determined the political reorganization of Central Europe for over a hundred years after the end of the Thirty Years War. They were treated as implementing provisions of the Peace of Westphalia and important additions and clarifications as the Reich's Basic Law and were included in full in the farewell of the Reichstag on May 17, 1654, called the Youngest Reichs Farewell .

The peace of Munster, Osnabrück and Nuremberg became the model for later peace conferences, as it helped to implement the principle of equality between states, regardless of their actual power. The imperial legal regulations of the Peace of Münster, Osnabrück and Nuremberg became part of the constitutional order of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation until its end in 1806. At the same time, the general peace - the pax universalis - of Münster and Osnabrück contributed to pan-European stability Later peace agreements up to the French Revolution were based on him again and again.

overview

Although not all European conflicts could be resolved in Münster and Osnabrück, important goals were achieved. The first success was the Peace of Munster , between Spain and the Netherlands , signed by the ambassadors on January 30th 1648. The exchange of the ratification documents with solemn evocation and public reading took place on May 15th and 16th 1648 in the town hall of Munster . The sovereignty of the United Provinces of the Netherlands was recognized and they left the Holy Roman Empire .

In Munster, however, it was not possible to find a solution to the most important hegemonic conflict of the time, as negotiations between France and Spain failed. A Spanish-French compromise only came about with the Peace of the Pyrenees of 1659. In this respect, the Peace of Westphalia was only a partial success of the congress.

The Westphalian peace treaties ended the Thirty Years' War in the Reich. The core of the regulations was a new imperial religion law. The rights of the imperial estates vis-à-vis the emperor and in their own territories were established on the basis of traditional principles. The Peace of Westphalia became a basic law of the empire and has been one of the most important parts of the imperial constitution ever since . In addition, the peace treaties also accepted the independence of the Swiss Confederation from the jurisdiction of the imperial courts (Art. VI IPO = § 61 IPM) and thus effectively recognized its state independence.

Despite its fragmentary character, the Peace of Westphalia was considered the basis of the system of European states until the French Revolution , which was only beginning to emerge around 1650. The reason for this judgment is the participation of many politically relevant powers in the Congress (important exceptions: Poland, Russia, England), their express mention in the Swedish-Imperial Treaty, the guarantee of compliance with the treaties by France and Sweden and the reference to them in later peace treaties.

Preparations for the Congress

Although the topic of the "Universal Peace Congress " had been negotiated between the warring parties since 1637, an agreement ( Hamburg Preliminary Peace ) on the participants and the places of the negotiations was not reached until December 1641 in Hamburg . Both negotiating cities and the connecting routes between them had been declared demilitarized in advance and all embassies were given safe conduct .

The real peace negotiations began in June 1645 and were conducted in Osnabrück directly, without mediation, between the imperial, the imperial and the Swedish envoys, in Münster, however, with papal and Venetian mediation between the imperial and French envoys. The separation took place partly to prevent disputes of rank between France and Sweden, partly because the Protestant powers and the Roman Curia did not want to negotiate with each other.

Emperor Ferdinand III. Initially resisted vehemently against the participation of the imperial estates in the negotiations, but was especially forced by France to allow the participation of the imperial estates. As a result, the congress in Osnabrück became, in addition to the negotiations between the Reich and Sweden, a German constitutional convention , while in Münster the European framework, the feudal problems and peace between Spain and the Republic of the Netherlands were also negotiated.

Rank and title disputes delayed the opening of the congress for a long time, as it was the first association of the ambassadors of the Central European states and the etiquette had to be completely reorganized.

People involved

On the French side, Henri II. D'Orléans , Duke of Longueville , a member of the high nobility, as well as the diplomats Claude de Mesmes , comte d'Avaux, and Abel Servien negotiated in Münster .

The following were authorized by Sweden: Johan Oxenstierna , the son of Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna , and Johan Adler Salvius .

The main imperial envoy (for both places) was Count Maximilian von Trauttmansdorff , in Münster he was supported by Count (later Prince) Johann Ludwig von Nassau-Hadamar and the lawyer Isaak Volmar , in Osnabrück Johann Maximilian von Lamberg and the Imperial Court Councilor Johannes Krane from Geseke were authorized , also a lawyer.

The Cologne Nuncio Fabio Chigi (later Pope Alexander VII ) and the Venetian diplomat Alvise Contarini were appointed as mediators .

From the Spanish court were Gaspar de Bracamonte y Guzmán conde de Peñaranda , Diego de Saavedra Fajardo , Antoine Brun , Joseph Bergaigne and others. a. present.

The States General had sent six plenipotentiaries, Adriaan Pauw and Willem Ripperda ; the Swiss Confederation represented Johann Rudolf Wettstein , Mayor of Basel . In addition, numerous imperial estates were represented.

Among the ambassadors of the evangelical estates stood out: the ambassador of Saxony-Altenburg, Wolfgang Konrad von Thumbshirn , the ambassador of Electoral Saxony Johann Ernst Pistoris , who together with Johann Leuber temporarily also held the chairmanship of the Corpus Evangelicorum , as well as the authorized representative of the House of Braunschweig- Lüneburg, Jakob Lampadius . The embassy from Kurbrandenburg was headed by Johann VIII von Sayn-Wittgenstein-Hohenstein .

For Kurtrier took Hugo Friedrich von Eltz part. Kurmainz was represented by Hugo Everhard Cratz von Scharfenstein and Nikolaus Georg Reigersberg . Franz Wilhelm von Wartenberg was envoy for Kurköln . For Bamberg the prefect of the cathedral chapter Cornelius Gobelius participated as envoy. Others, such as the envoy from Württemberg, Johann Konrad Varnbüler , contributed significantly to the later regulations through their close contacts with Sweden. Adam Adami , envoy from the Abbot of Corvey , was the congregation's historian.

negotiations

During the negotiations, the war continued unabated and the military successes of the foreign powers had a significant impact on the negotiations.

Although the participation of the imperial estates in the negotiations was repeatedly called for ( admission dispute ), the emperor initially represented the empire alone. A Reichsdeputationstag , which has met in Frankfurt since 1642/43 , on the other hand, discussed the constitutional problems of the Reich. Accordingly, the Swedish envoy Johan Adler Salvius suggested as early as 1643 to usurp the rights of majesty and formulated: Your security consists in the German estates liberty .

The Swedish general Torstensson even penetrated the imperial hereditary lands as far as the Danube in 1645, and on July 15, 1648 , Königsmarck conquered the Lesser Town of Prague . This was the decisive factor in the long and difficult negotiations, and both peace treaties were signed in Munster on October 24, 1648 . It was not until almost four months later, on February 18, 1649, that the instruments of ratification were exchanged, and various negotiations about the implementation of the peace provisions continued for a long time. The demobilization process , which involved a large payment of money to Sweden, required new negotiations, which took place in Nuremberg from May 1649 and ended with two agreements on June 26, 1650 and July 2, 1650. The protest against the religious law provisions of the treaties lodged by the Holy See in August 1650 against the peace treaty and dated back to November 26, 1648 remained ineffective.

Provisions of the Peace of Westphalia

Territorial changes

In addition to war compensation of 5 million thalers, Sweden received all of Western Pomerania alongside the island of Rügen and the estuary islands of Usedom and Wollin , as well as Stettin and a strip on the right bank of the Oder to be determined; also the city of Wismar with the offices of Poel and Neukloster of the Duchy of Mecklenburg , the Hamburg Cathedral Chapter, the Archbishopric of Bremen and the Monastery of Verden . All these areas were to remain German imperial fiefs, and Sweden was to have them as a German imperial estate with a seat and vote in the imperial and district assemblies.

The Elector of Brandenburg received the rest of Pomerania and, as compensation for Western Pomerania, to which his house had inheritance rights after the Pomeranian ducal dynasty (1637) had expired, the Archbishopric of Magdeburg and the monasteries of Halberstadt , Minden and Cammin ; but Magdeburg remained in the possession of the administrator at that time, the Saxon Prince August, until 1680. Duke Adolf Friedrich von Mecklenburg-Schwerin received the Hochstifte Schwerin and Ratzeburg for the assignment of Wismar . The Duchy of Braunschweig-Lüneburg was granted the succession of power in the bishopric of Osnabrück , alternating with a Catholic bishop elected by the cathedral chapter (alternative succession), and the monasteries Walkenried and Gröningen were left. The Landgraviate of Hessen-Kassel received the princes of Hersfeld Abbey and part of the former Grafschaft Schaumburg . Bavaria remained in the possession of the Upper Palatinate and electoral dignity. Die Rheinpfalz was with the newly created eighth Electorate and the Erzschatzmeisteramt the son of the outlaw Frederick V , Karl Ludwig returned ( Causa palatina ) .

France received the bishoprics and cities of Metz , Toul and Verdun , the so-called Trois-Évêchés , which it had actually owned since 1552. Furthermore, the emperor ceded to the Crown of France all rights that both the House of Austria and the Empire had hitherto had over the city of Breisach , the Landgraviate of Upper and Lower Alsace , the Sundgau and the governor of the ten united imperial cities in Alsace .

The Confederation was recognized as independent from the Holy Roman Empire . In the Peace of Munster , part of the Peace of Westphalia, the independence of the Netherlands was formally recognized. However, the Netherlands had been , de facto, an independent state since 1579 and no longer owned by the Spanish Crown. With the Peace of Munster, however, the independence and sovereignty of the Netherlands was also established de jure. With this recognition, the Netherlands left the Imperial Union of the Holy Roman Empire at the same time, although they had held a special position within the empire since the 15th century. Apart from these changes, the peace stipulated an unlimited amnesty for everything that had happened since 1618, and a restitution of the ecclesiastical property of 1624 in the so-called normal year. Only the emperor achieved an exception for his hereditary lands by only recognizing the key year 1630 for the restitution of property and property of his subjects.

Church and Political Affairs

On the ecclesiastical question, the peace confirmed the Passau Treaty and the Augsburg Religious Peace and now included the Reformed in the legal status previously only granted to Augsburg relatives. All three denominations, the Catholic , the Lutheran and the Reformed , were completely equated; the Protestant minority could not be outvoted on religious matters at the Reichstag. The Reformation Anabaptists continued to be excluded from legal recognition at the imperial level. The dispute over the spiritual monuments and goods was settled with the repeal of the edict of restitution of 1629 to the effect that 1624 should be the normal year and that the Protestant and Catholic possessions should remain or be restored as they had been on January 1, 1624. However, the imperial hereditary lands were also excluded from this, in which the emperor was able to assert the unrestricted sovereign right of Reformation with a few exceptions. The territorial sovereignty of the imperial estates was expressly recognized and the right to enter into alliances with one another and with foreign powers for their preservation and security was confirmed. These could only not be directed against the emperor and the empire. The new constitution of the Reich should be discussed at the next Reichstag.

For the confessionally mixed imperial cities of Ravensburg , Biberach and Dinkelsbühl in southern Germany, an equal government and administrative system was introduced (equal rights and exact distribution of offices between Catholics and Protestants, see Equal Imperial City ). In Augsburg the parity was already anchored in the city constitution of 1548 and was confirmed by this treaty.

Rating and outlook

The Peace of Westphalia was a compromise between all parties involved, which became possible because neither side could gain anything by continuing the war due to the total exhaustion of resources and the general weariness of the war. In addition to a revised religious peace, the extensive set of rules also includes extensive provisions on the constitutional relationships of the empire, which are intended to achieve a balance between the emperor and the imperial estates. This made the peace treaty the most important document of the imperial constitution alongside the golden bull . Many of the political compromises set out in it still have an effect today. Questions that remained unanswered in the treaty, in particular on the issue of troop withdrawal, were resolved in the following months at the Peace Execution Congress in Nuremberg .

According to today's understanding, the Peace of Westphalia is seen as a historical contribution to a European peace order of equitable states and as a contribution to the peaceful coexistence of denominations. The negotiations in Münster, Osnabrück and Nuremberg are at the beginning of a development that has led to the development of modern international law , which is why political science sees here the foundations of the sovereign nation state . When considering international relations, political science refers explicitly but not exclusively to the interaction between sovereign states, the so-called Westphalian system . Realism calls for this to be maintained .

Many contemporaries welcomed peace as the long-awaited end to a decade-long war. Up until the end of the 18th century, Protestants in particular regarded it as the foundation of imperial liberty and the source of the religious freedom of the imperial estates . On the other hand, the Pope was critical of the religious peace and the subsequent wars of Louis XIV, especially the Dutch War , were not prevented by the Peace of Westphalia. In 1748 a large number of medals were struck in the German states for the Peace of Westphalia, which show the great importance that this peace was still attached to 100 years later.

It was not until the 19th century that the assessment in Germany from the perspective of Little German-Prussian nationalism, but also from the greater German perspective, became gloomy. Peace was dismissed as a shame and humiliation for Germany; the Holy Roman Empire is seen as the defenseless prey of the "hereditary enemy" of France. During the time of National Socialism , this assessment became even more acute. The peace treaty was instrumentalized for anti-French propaganda .

Today, the emergence of the German nation state is no longer the only yardstick for evaluating historical events. The latest research therefore sees the Peace of Westphalia as the beginning of a new balance of power and cooperation between the imperial estates, the emperor and the institutions of the empire.

The European dimension of the treaty (particularly concerning Switzerland and the Netherlands) should not be overlooked.

See also

- Augsburg High Peace Festival ( August 8th ), public holiday in the city of Augsburg

Movies

- 1648 - The long road to peace. 89-minute television documentary by Holger Preuße (WDR, Germany 2018)

literature

- Franz Bosbach : The Costs of the Westphalian Peace Congress. A structural-historical investigation . Aschendorff, Münster 1984, ISBN 3-402-05632-1 .

- Klaus Bußmann , Heinz Schilling : 1648 - War and Peace in Europe, catalog volume and two text volumes, Münster 1998 [Documentation of the Council of Europe exhibition for the 350th anniversary of the Peace of Westphalia in Münster and Osnabrück.] Münster / Osnabrück 1998, ISBN 3-88789-127 -9 .

- Fritz Dickmann : The Peace of Westphalia. Münster , 7th edition. Aschendorff Verlag, Münster 1998, ISBN 3-402-05161-3 .

- Heinz Duchhardt (Ed.): Bibliography on the Peace of Westphalia . Edited by Eva Ortlieb and Matthias Schnettger. Münster: Aschendorff, 1996 (= series of publications by the Association for Research into Modern History 26), ISBN 3-402-05677-1 .

- Heinz Duchhardt: The Peace of Westphalia. Diplomacy - political turning point - cultural environment - history of reception. Munich 1998, ISBN 3-486-56328-9 .

- Dorothée Goetze, Lena Oetzel (ed.): Why making peace is so difficult. Early modern peace-finding using the example of the Westphalian Peace Congress. Aschendorff, Münster 2019 (= series of publications on modern history 39th NF 2), ISBN 978-3-402-14768-9 .

- Herbert Langer: The Diary of Europe. Sixteen hundred and forty-eight, the Peace of Westphalia. Brandenburg. V., Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-89488-070-8 .

- Christoph Link : The importance of the Peace of Westphalia in the development of the German constitution. For the 350th anniversary of a Reich constitution. In: Legal journal . 1998, pp. 1-9.

- Eva Ortlieb, Heinz Duchhardt (Ed.): The Westphalian Peace. Oldenbourg, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-486-64425-4 .

- Roswitha Philippe: Württemberg and the Peace of Westphalia. Aschendorff, Münster 1976, ISBN 3-402-05627-5 . (= Series of publications of the Association for the Study of Modern History 8)

- Michael Rohrschneider: The failed peace of Münster. Spain's struggle with France at the Westphalian Peace Congress (1643–1649). Aschendorff, Münster 2007, (= series of publications by the Association for Research into Modern History 30), ISBN 3-402-05681-X .

- Anton Schindling : The Peace of Westphalia and the Middle Rhine-Hessian state history. Some thoughts on the Bonn edition of the Acta Pacis Westphalicae, in: Nassauische Annalen 89, 1978, pp. 240-251.

- Anton Schindling: The Peace of Westphalia and the Reichstag, in: Hermann Weber (Hrsg.), Political Orders and Social Forces in the Old Reich (= publications of the Institute for European History Mainz, Supplement 8). Wiesbaden 1980, pp. 113-153.

- Anton Schindling: The Peace of Westphalia and the German Confessional Question, in: Manfred Spieker (Hrsg.), Friedenssicherung, Vol. 3: Historical, political science and military perspectives. Münster 1989, pp. 19-36.

- Anton Schindling: Art. "Westphalian Peace", in: Concise Dictionary of German Legal History (HRG), Vol. 5, Berlin 1998, Sp. 1302–1308.

- Anton Schindling: The Peace of Westphalia and the coexistence of denominations in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, in: Konrad Ackermann / Alois Schmid / Wilhelm Volkert (eds.), Bavaria. From the tribe to the state. Festschrift for Andreas Kraus on his 80th birthday, Vol. 1, Munich 2002, pp. 409–432.

- Georg Schmidt : History of the Old Kingdom. State and Nation in the Early Modern Age 1495–1806. Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-45335-X .

- Benno Teschke : Myth 1648 - Classes, Geopolitics and the Origin of the European State System. Münster 2007, ISBN 978-3-89691-122-3 .

- Anuschka Tischer : French diplomacy and diplomats at the Westphalian Peace Congress. Foreign policy under Richelieu and Mazarin. Aschendorff, Münster 1999, ISBN 3-402-05680-1 . (= Series of publications of the Association for the Study of Modern History 29)

- Siegrid Westphal : The Peace of Westphalia . Beck, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-68302-2 .

- Manfred Wolf: The 17th Century. In: Wilhelm Kohl (Hrsg.): Westphalian history. Volume 1. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1983, pp. 537–685, bes, ISBN 3-590-34211-0 , pp. 561 ff. (= Publications of the Historical Commission for Westphalia, XLIII)

swell

-

Acta Pacis Westphalicae . Münster / Westphalia, 1962 ff. (File edition, so far 44 volumes published)

- Series I: Instructions

- Series II: Correspondences

- Series III: minutes, negotiation files, diaries, varia; in particular Series III, Section B: Negotiation Files, Vol. 1: The Peace Treaties with France and Sweden (in 3 volumes), Aschendorff, Münster 2007

- The diplomatic correspondence between Elector Maximilian I of Bavaria and his envoys in Münster and Osnabrück, 2000 ff. (3 volumes so far published)

- Volume 1: Gerhard Immler : The instructions from 1644 . Munich 2000, ISBN 978-3-7696-9704-9 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- Volume 2.1: Gabriele Greindl Gerhard Immler: The diplomatic correspondence between Elector Maximilian I of Bavaria and his ambassadors in Münster and Osnabrück. December 1644 - July 1645 . Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-7696-6612-0 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- Volume 2.2: Gabriele Greindl, Gerhard Immler: The diplomatic correspondence between Elector Maximilian I of Bavaria and his envoys in Münster and Osnabrück. August - November 1645 . Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-7696-6614-4 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- Volume 3: Gabriele Greindl, Günther Hebert, Gerhard Immler: The diplomatic correspondence between Elector Maximilian I of Bavaria and his envoys in Münster and Osnabrück. December 1645 - April 1646 . Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-7696-6617-5 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- Ferdinand III., Ludwig XIV .: Peace of Westphalia - Treaty of Münster ( Instrumentum Pacis Monasteriensis ). Official German translation, Philipp Jacob Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1649.

- Ferdinand III., Kristina of Sweden: Peace of Westphalia - Treaty of Osnabrück ( Instrumentum Pacis Osnabrugensis ). Official German translation, Philipp Jacob Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1649.

- Georg Christoph Gack : Peace Agreement of Westphalia. Newly translated and published with the Latin original for the bicentenary of the peace treaty. JE v. Seidel, Sulzbach 1848.

Web links

- Research Center Westphalian Peace

- Westphalian Peace Office

- Search for Peace of Westphalia in the German Digital Library

- Treaty text of the Muenster Peace Treaty in the translation by Arno Buschmann

- Marco Jorio: Peace of Westphalia. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

Individual evidence

- ↑ See both contract texts on the Westfälische Geschichte Internet portal , see section Weblinks / Sources.

- ↑ quoted from Georg Schmidt, p. 178.

- ^ Johannes Arndt: The Thirty Years War , ISBN 978-3-15-018642-8 , pp. 238 and 228.