Osoblaha

| Osoblaha | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Basic data | ||||

| State : |

|

|||

| Region : | Moravskoslezský kraj | |||

| District : | Bruntál | |||

| Area : | 2579 ha | |||

| Geographic location : | 50 ° 17 ' N , 17 ° 43' E | |||

| Height: | 220 m nm | |||

| Residents : | 1,096 (Jan 1, 2019) | |||

| Postal code : | 793 99 | |||

| traffic | ||||

| Railway connection: | Třemešná ve Slezsku – Osoblaha | |||

| structure | ||||

| Status: | city | |||

| Districts: | 1 | |||

| administration | ||||

| Mayor : | Dagmar Machaňová (as of 2012) | |||

| Address: | Na Náměstí 106 793 99 Osoblaha |

|||

| Municipality number: | 597716 | |||

| Website : | www.osoblaha.cz | |||

Osoblaha (German Hotzenplotz ) is a town in Okres Bruntál in the Czech Republic ( Freudenthal district ).

Geographical location

The city is located in the Sudetes in the Osoblaha microregion on the left bank of the Osobłoga , about 14 kilometers northeast of Głubczyce ( Leobschütz ) and 19 kilometers north of Krnov ( Jägerndorf ).

name of the city

In Czech, German and Polish, the city bears the name of the river on which it lies: Osoblaha, Hotzenplotz or Osobloga.

The Breslau researcher Heinrich Adam suspected in 1888 a pre-Slavic river name 'Ossa', which then became a Slavic 'Ossoblavia' or 'Ossoblaka', "flowed around by the Ossa" or "... flowed through".

The German name Hotzenplotz is a corruption of the Slavic.

history

Since the 10th century there have been Bohemian-Polish armed conflicts around the area, which only ended in 1137 with the Pentecostal Peace of Glatz . Due to the subsequent demarcation, the area around Osoblaha remained with Bohemia. However, the near border gave rise to the development of the town-like settlement as a north-eastern Moravian border fortress. The topographical location on the plateau of a hill was a good prerequisite for this. The expansion of the city began under the Olomouc bishop Robert of England . The construction of the parish church of St. Maria Magdalena in the Gothic style began, as well as the construction of the Nikolaikapelle outside the city. It can be assumed that the city was founded around 1235.

The peaceful development of the region was interrupted in 1241 by the Mongol invasion . The Tatars roamed the country, murdering and plundering. The city was destroyed, the residents fled, were killed or deported. The area was depopulated. The few survivors were unable to rebuild the scorched land.

During this time, Bruno von Schauenburg was appointed to the Olomouc bishopric by Pope Innocent IV. Under the protection of the Bohemian King Ottokar II. Přemysl , he brought German settlers from Saxony, Bavaria, Franconia and Swabia to the country. Forests were cleared, fields were created, villages and settlements were established. This took place in the period up to 1267.

In 1260 the city was rebuilt, reinforced with walls, gates and towers, and surrounded by ramparts and moats. This created a border fortress for the Moravian bishopric in Olomouc. As the property of the Olomouc bishopric , the enclave of Hotzenplotz was a fiefdom of the kings of Bohemia and thus part of the Holy Roman Empire . This emerges from the Golden Bull of Charles IV . The city was a Moravian exclave in Silesia until 1918/20 and as such belonged to the Crown Land of Moravia, but in the area of state administration to the Lieutenancy of Silesia.

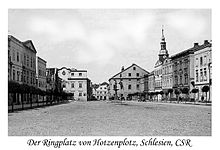

The city was re-founded in accordance with Magdeburg city law around 1250. The bishops of Olomouc used the title "Duke of Hotzenplotz" in all documents and documents. Economic development was disrupted several times by wars, raids and looting. This included the long-standing clashes with Poles, Hungarians and the Hussites , who roamed the country in 1428, pillaging. The city was often burned down and rebuilt. Even in peaceful times it happened that careless handling of fire set fire to the easily inflammable houses. The city's layout remained unchanged for more than 500 years and retained the old street names Ringplatz, Binder-, Töpfer-, Färbergasse until it was completely destroyed in March 1945.

When Jews were expelled from Prague during the Hussite period, in 1415 the Bishop of Olomouc allowed Jewish families to settle in Hotzenplotz. Gradually the Jewish population grew, as did their share of the city's total population. In 1616 there were e.g. B. 135 Jewish families in 32 houses. (For comparison: at that time Hotzenplotz had 282 houses of Christian families.) In 1808 the Jewish community built a synagogue . The Jewish cemetery was in the area of the k. and k. Second largest monarchy after that in Prague. In 1802 the highest number of Jewish residents was 845. In the middle of the 19th century, most of the Jews left the city for economic reasons.

Wars of religion and the Reformation in the 16th century did not leave the Hotzenplotzer Ländchen untouched. Luther's teachings also found their way here and divided the population into two parties. The prosperity achieved was severely affected as the parties feuded violently.

The Thirty Years War brought renewed unrest. Mercenary armies of the warring parties roamed the country, plundered and had to be fed, contributions and exemption taxes had to be paid. Hotzenplotz was occupied by troops several times. Famine, epidemics and disease broke out. The plague claimed considerable victims. There were witch hunts . Another victim of the witch trials was Christoph Alois Lautner , pastor and dean in Hotzenplotz. Many residents had fled.

In order to be able to defend against enemies in the future, the Bürgerliche Schützengesellschaft was founded in 1656 as the city's oldest association. In this time of need and misery, lace was introduced around 1700 from the Ore Mountains. The city was slow to recover.

The Silesian Wars and the War of the Bavarian Succession shortly afterwards covered the country with new calamities. Frederick the Great attacked Silesia , the duchies of which were placed between 1289 and 1369 as a fiefdom under the Crown of Bohemia , which the Habsburgs held from 1526 . The Hotzenplotz enclave was also repeatedly occupied by Prussian troops. The population was exploited by enormous burdens, because the armies of both warring parties and their auxiliaries had to be accommodated and fed. Horses and wagons were available. Resistance led to looting, pillage and other contributions. Despite these difficulties, the Franciscan Father Petrus Regalati was able to rebuild the Nikolaikapelle into a church from 1767–1768 through donations.

Archduchess Maria Theresa , in her capacity as Queen of Bohemia, finally had to cede most of Silesia to Prussia. Only a small part, the later Austrian Silesia , to which the enclave Hotzenplotz also belonged, remained with the Habsburg monarchy in 1742. This demarcation remained until recently and was of considerable economic disadvantage for the city, as it lost a large part of its natural economic area.

The great wars of the 19th century between Germans, French and Austrians up to the First World War did not affect the area. Despite high taxes and levies, these wars could not be compared with those of earlier times. As part of the administrative reforms under Maria Theresa and her son Joseph II , trade, crafts and agriculture flourished. The abolition of the robot requirement in 1848 contributed significantly to this.

A district court, tax office, customs office, calibration office, post office and telegraph office, elementary and citizen school (1870/72), municipal savings bank, rectory, hospital, foundation for poor relief, volunteer fire brigade, shooting range, lace making, agricultural vocational school (1908), Annual and livestock markets. The sugar factory started operations in 1858; the Hotzenplotz – Röwersdorf narrow-gauge railway was put into service in 1898. A new water pipe was laid and a gas plant was built in 1911. The planned establishment of a match factory and a button factory could not be realized. Cultural and club life also flourished. A district teachers' association, men's choir, mixed choir, rifle club, veterans association, ice skating association, gymnastics association, Christian youth association emerged.

In 1880 Hotzenplotz had 4012 inhabitants. After that, the population decreased. As a result of the border being drawn with neighboring Upper Silesia , the new railway line was led around Hotzenplotz on the Prussian side; the narrow-gauge railway Hotzenplotz – Röwersdorf could not compensate for this. Economic development was affected; many young people had to look for work abroad or immigrated forever.

During the First World War , almost all men between the ages of 18 and over 50 were called to arms. Many of them never returned. In 1918 the Austro-Hungarian monarchy collapsed. Relations with Vienna broke off, and the border with Silesia became more noticeable. The sugar factory, founded in 1850, was the city's largest employer until 1920, after which it was relocated to Zülz and Oberglogau in neighboring Upper Silesia.

After the establishment of Czechoslovakia in 1918 after the end of the war, the Prague government endeavored to occupy the public administration with Czech border officials, gendarmes, state police, and post officials. The Germans were expected to learn the Czech language. The great unemployment during the Great Depression of the 1920s, which largely affected German workers, was also an enormous burden. The population decreased to about 2500 due to emigration; the Jewish community almost completely disappeared. The old dilapidated synagogue was torn down.

In 1938, when the Munich Agreement was implemented , German troops took possession of the city and were welcomed as liberators. The border with Silesia was lifted and there was hope that the economy would recover. The city in the district of Jägerndorf had to accept resettlers from the occupied areas of Volhynia and Bessarabia during the Second World War . Women, children and old people from Berlin, Hamburg and the Ruhr area who were injured or at risk of air warfare were also quartered.

In 1945 the town of Hotzenplotz belonged to the district of Jägerndorf in the Reichsgau Sudetenland , district of Troppau , of the German Empire .

Towards the end of the Second World War , at the beginning of 1945, the people from Upper Silesia, fleeing from the approaching front, came to the city in carts of horses and oxen. On March 17, 1945, the Red Army stood before Hotzenplotz. Almost all residents of the city fled over the Galgenberg and Zottig in the direction of the Jeseníky Mountains.

Hotzenplotz was hotly contested and the occupiers changed several times. Around 200 Soviet tanks were destroyed in a tank battle. On March 21, the Red Army occupied Hotzenplotz for good. What was not destroyed by artillery fell victim to fire. The fronts held on Zottiger Berg until May 7, 1945.

In May and June 1945, the people who had fled to North Moravia and the Jeseníky area gradually returned to the destroyed city. Most of the houses were no longer habitable; often quarters were set up in the rubble. After the end of the war, all male German persons between the ages of 14 and 60 were obliged to do forced labor. They came to the coal mines in Ostrava or in the interior of Bohemia. In the spring of 1946 the expulsion of the German population from Osoblaha began. Up until autumn 1946, transports from Jägerndorf ( Krnov ) to Bavaria, Baden-Württemberg and Hesse went in cattle wagons with 40 people each .

The center of the city was completely destroyed at the end of World War II. At the entrance to the Ringplatz, a Soviet anti-aircraft gun commemorates the long battles and the victory of the Red Army over the Wehrmacht.

Demographics

| year | Residents | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1834 | 3,558 | German residents, including 2,971 Catholics and 587 Jews |

| 1857 | 3,000 | |

| 1900 | 3,199 | German residents |

| 1930 | 2,237 | |

| 1939 | 2.138 | |

| 1947 | 421 |

City structure

Osoblaha is divided into the cadastral communities: Osoblaha and Studnice (1880 Jizbičko , 1921 Štundorf , German Stubendorf , Polish Studnica , 1880 Izbećka ).

Attractions

- The town has an old Jewish cemetery with graves from the 17th century that borders the 16th century city wall. It is a listed building .

- The baroque church of St. Nicholas is located at the cemetery.

- Between Osoblaha ( Hotzenplotz ) and Třemešná ( Röwersdorf ) a narrow-gauge railway with a track width of 760 mm has been running since 1898 . This is the only narrow-gauge railway line operated by the Czech state railway company České dráhy .

Nature reserves

The Velký Pavlovický rybník nature reserve is located near Osoblaha . Part of the Lužní primeval forest is located in the “Jungle” nature reserve .

Sons and daughters of the church

- Franz Xaver Joseph Richter (1783–1856), historian and librarian

- Berthold English (1851–1897), chess master

- Oskar Gutwinski (1873–1932), Gesenke mountain dweller (“the old man from the mountains”) and skiing pioneer

- Reinfried Keilich (1938–2016), actor, author and dramaturge

Personalities

- Rudolf Grünn (1853–1930), President of Hotzenplotzer Zuckerfabrik AG

- Josef Walter König (1923–2007), writer

- Adolf Meese (1830–1912), former mayor and honorary citizen of Hotzenplotz, President of the Zuckerfabrik AG

- Edwart Richter (1821–1898), chronicler of the Moravian enclave of Hotzenplotz

Trivia

Otfried Preußler named his fictional character Räuber Hotzenplotz after the place, because he met the name as a child, made a strong impression on him and was always remembered.

literature

- Faustin Ens : The Oppaland, or the Troppauer Kreis, according to its historical, natural history, civil and local characteristics . Volume 4: Descriptions of the principalities of Jägerndorf and Neisse, Austrian Antheils, and the Moravian enclaves in the Troppauer district , Vienna 1837, pp. 125–131.

- Josef Chowanetz, Alois Wurst: The Hotzenplotzer school district . Damasco, 1890.

- Adolf Christ: History of the City of Hotzenplotz . Hotzenplotz 1926.

- Adolf Christ: History of the Hotzenplotz District (Moravian Enclave) . Hotzenplotz (around 1930).

- Franz Blaschke: memorial sheets. Published on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the destruction and the seven hundredth anniversary of the founding of the city and enclave of Hotzenplotz . Sparneck 1955.

- Heimo Biedermann: Parish letters for the dean's office Hotzenplotz and the surrounding area , 1946–1970, ISBN 3-88347-231-X .

- Jaroslav Klenovský: Židovská obec v Osoblaze (Jewish community in Hotzenplotz). Židovská obec, Olomouc 1995.

- Wilhelm J. Wagner: picture atlas of German history . Chronik-Verlag, Gütersloh 1999.

- Vladan Hruška: Udržitelný rozvoj venkovské krajiny v rozdílných přírodních a sociálních podmínkách (Sustainable Development of Rural Regions under Different Natural and Social Conditions), Masarykova univerzita - Přírodovědecká, Geústý Brickno 2007.

- Jaromír Balla: Osoblažsko oknem úzkokolejky: loupežník Hotzenplotz průvodcem svým krajem (Through the window of the Hotzenplotzer narrow-gauge railway: Robber Hotzenplotz as a leader in his region). Advertis, Krnov 2010, ISBN 978-80-900907-2-9 .

- Radim Lokoč, Ondřej Dovala, Petr Chroust, Miroslav Přasličák: Ovoce Opavska, Krnovska a Osoblažska (PDF; 10.2 MB) (The fruit culture in the districts of Troppau, Jägerndorf and Hotzenplotz). Místní akční skupina Opavsko and Místní akční skupina Rozvoj Krnovska, Opava 2011, ISBN 978-80-254-5803-7 .

Web links

- Osoblaha website (Czech)

- Třemešná – Osoblaha narrow-gauge railway

- Philipp Eichhoff: Osoblaha , published in the blog In old and new cities , March 12, 2020

Individual evidence

- ↑ Český statistický úřad - The population of the Czech municipalities as of January 1, 2019 (PDF; 7.4 MiB)

- ↑ Faustin Ens : The Oppaland or the Opava district, according to its historical, natural history, civic and local peculiarities . Volume 4: Description of the locations of the principalities of Jägerndorf and Neisse, Austrian Antheils and the Moravian enclaves in the Troppauer district , Vienna 1837, p. 126.

- ^ Carl Kořistka : The Margraviate of Moravia and the Duchy of Silesia in their geographical relationships . Vienna and Olmütz 1861, pp. 268–269 .

- ^ Meyer's Large Conversational Lexicon . 6th edition, Volume 9, Leipzig and Vienna 1907, p. 587.

- ^ A b Michael Rademacher: German administrative history from the unification of the empire in 1871 to the reunification in 1990. Jägerndorf district. (Online material for the dissertation, Osnabrück 2006).