Reich presidential election 1925

The presidential election in 1925 was prematurely necessary in the Weimar Republic because the first Reich President Friedrich Ebert died unexpectedly on February 28, 1925. The first ballot took place on March 29, 1925. None of the candidates achieved the necessary majority. In the second and decisive ballot on April 26, 1925, Wilhelm Marx faced each other for the republican “people's bloc” and Paul von Hindenburg for the anti-republican “Reichsblock”; the candidate of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), Ernst Thälmann , was an outsider. Hindenburg won, was confirmed in the office of Reich President in 1932 and held it until his death on August 2, 1934.

Office and electoral process

The Weimar Constitution endowed the office of Reich President with a number of important powers. According to Article 48, the Reich President could actively intervene in the legislation by issuing emergency ordinances . Article 25 gave him the right to dissolve the Reichstag early. The right to appoint and dismiss the Reich Chancellor was also one of his powers. In addition, under Article 47, the Reich President had the military command. With these rights, the Reich President was able to introduce a "temporary dictatorship". The term of office was seven years, multiple re-elections were possible. The minimum age of the Reich President was 35 years. He was elected according to Article 41 "by the whole German people" . More detailed information on the election can be found in the “Law on the Election of the Reich President” of May 4, 1920. It provided for general, equal, direct and secret elections. In the first ballot an absolute majority was necessary, in the second a relative majority of votes was sufficient. New candidates could be nominated for the second ballot.

After Ebert's death, who was not directly elected by the people but by the Weimar National Assembly , the Reich government first considered whether Reich Chancellor Hans Luther should take over the office of Reich President until the presidential election . However, this idea was quickly rejected. Instead, with the "Act on the Deputy of the Reich President" of March 10, 1925, the President of the Reich Court , Walter Simons , was appointed provisionally to hold the highest office of the state until a regular successor was elected.

Political background of the election

When the Reich presidential election of 1925 took place, the Weimar Republic had a series of existential crises behind it, including the Kapp Putsch , inflation and hyperinflation , the occupation of the Ruhr , the communist attempts at insurrection in Thuringia and Saxony as well as in Hamburg , the Hitler-Ludendorff Coup and the numerous political murders are counted. The republic was spared from turbulence of this magnitude in the years 1924 to 1929/1930, but only a relative stabilization occurred. For politics this meant above all that the governments of these middle years worked with changing majorities. Their lifespan was also often comparatively short. "A stable parliamentary system of government did not develop in the phase of 'relative stabilization'". Another indication of the only apparent normality was the continued effect of broad anti-democratic and anti-republican currents. The opponents of the republic from the left and from the right were pushed back, but not marginalized or finally defeated. Opposition to the republic was not a marginal phenomenon; with the participation of the German National People's Party (DNVP) in the Luther cabinet , it had moved into the center of the political system since mid-January 1925.

An indirect consequence of the hostility to the republic was the death of the first president of the Weimar Republic. Friedrich Ebert died on February 28, 1925 at the age of 54 of a delayed peritonitis and appendicitis . He had delayed the treatment in order to defend himself against defamation in court in Magdeburg in the second instance . Erwin Rothardt, a German-ethnic journalist, had previously accused Ebert of treason because he had co-organized a strike movement that lasted several days in January 1918. On December 23, 1924, the court had imposed a three-month prison sentence on the journalist in the first instance for insulting , but in the eyes of the judges there was no defamation of the Reich President, because the offense of treason had actually existed in early 1918. This court ruling, which made Ebert such a serious criminal offense in the grounds of the verdict, provoked protests from the Republican public. The Marx government also stood behind the president by publishing a declaration of honor. The prosecution's representative also appealed against this first-instance judgment. Ebert, however, was hit: "The judgment had its effect, and it worked like poison."

Preparations for the first ballot

Initially, the democratic parties considered putting up a joint applicant. In negotiations between the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the German Democratic Party (DDP), the German Center Party (Zentrum) and the German People's Party (DVP), Otto Geßler (DDP) emerged as a possible common candidate. Both nationalist circles and politicians of the left opposed the long-serving Reichswehr Minister . Gessler was said to have had private affairs from nationalist circles. The left circulated speculation that France would react with compromising revelations about the illegal Black Reichswehr and the Orgesch if Geßler actually became President. The decisive factor, however, was Gustav Stresemann's resistance , who voiced foreign policy concerns. Against this background, the attempts to reach an agreement between the four parties failed. Gessler did not take office and remained Minister of Defense. At the same time there were considerations to have Walter Simons run as a bourgeois collective candidate. However, they failed because of resistance from the DVP and DNVP. The DDP proposal to set up Simons as a “Weimar candidate” met with disinterest from the center and the SPD. A large number of other personnel suggestions for collective candidates also fizzled out, so that in the first ballot mostly applicants competed who were tied to individual parties.

The DVP supported the Lord Mayor of Duisburg and former Reich Interior Minister Karl Jarres . To this end, she had founded an alliance called the “Reichsblock” with the economic party and the anti-republican DNVP. The Reichsblock was actively coordinated by the former Prussian Interior Minister Friedrich Wilhelm von Loebell , who hoped that the victory of a right-wing bourgeois candidate would lead to a state restructuring in the conservative sense. The SPD first named Paul Löbe, who has been President of the Reichstag for many years . After his rejection, she chose Otto Braun , who had ruled as Prime Minister in Prussia until January 1925 . Braun also hesitated because he expected defeat and also wanted to remain active in Prussian state politics. However, massive pressure from the SPD leadership made him give in. The DDP called for the election of the Baden state president Willy Hellpach . The party leader Wilhelm Marx, who had been Chancellor of the Reich from late 1923 to late 1924, applied to represent the center . The KPD nominated Ernst Thälmann, who at the time was still little known outside of Hamburg . Bavaria's Prime Minister Heinrich Held was appointed by the Bavarian People's Party . Erich Ludendorff , Quartermaster General of the Third Supreme Army Command during the First World War, ran for the Völkische and the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), which was only founded in February 1925 .

Due to the large number of candidates, no decision was expected in the first ballot. The job of the applicants was rather to act as counting candidates to indicate the strength of the respective nominating parties and to provide them with good negotiating positions for the second ballot when it came to agreeing on collective candidates.

Result of the first ballot

As expected, March 29, 1925 brought no decision. None of the applicants achieved the necessary absolute majority in the first ballot. Jarres and Braun were able to tap the electoral potential that the parties that supported them had achieved in the Reichstag election of December 1924 . Hellpach and Marx did not quite reach the comparative values of that Reichstag election, but their losses were only of limited extent. Held, on the other hand, fell more than half a million votes behind the numbers that BVP and Bayerischer Bauernbund had achieved in December 1924. The weaknesses of the applicants presented by the extremist parties were even clearer. Thälmann achieved 800,000 fewer votes than the KPD four months earlier. Ludendorff also received 600,000 fewer votes than the list connection between the National Socialists and the Deutschvölkischer Freedom Party had achieved in December 1924. This alliance had broken up in the meantime, and in the spring of 1925 the Völkische supported Jarres, not Ludendorff. The turnout was 68.9 percent, around ten percentage points lower than in the previous Reichstag election. This lower participation was mainly at the expense of the wing parties.

Preparation for the second ballot

Marx as a candidate for the popular bloc

Since the relative majority would suffice in the second ballot, it was important for the parties of the Weimar coalition - SPD, DDP and Zentrum - to agree on a common candidate this time. Of these three parties, Otto Braun, the SPD candidate, did best in the first ballot, but it was known from the elections in the German Empire that voters of the bourgeois parties hardly supported social democratic politicians in runoff elections . The nomination of a candidate who belonged to the center or the DDP was therefore much more promising. Wilhelm Marx, behind Braun in the first ballot with the third-best result, was not considered particularly popular. He was also a Catholic, which led to reservations among Protestant voters. Nevertheless, it made sense to resort to Marx. In the first ballot he had done significantly better than the DDP candidate Hellpach and an agreement on him could be linked to a political swap: Marx and Braun each toied with the office of Prussian Prime Minister, which both had already held. In the event that Braun were elected Prime Minister with the help of the Center MPs in the Prussian state parliament, the SPD agreed to support Marx's candidacy for Reich President. Braun became Prime Minister of Prussia on April 3, 1925 with the help of this agreement. On the same day, the SPD, DDP and the center agreed on Marx as their common candidate. The three parties formed an alliance for the election campaign called the “People's Block”. As a result of this compensation deal, they expressly stuck to Marx when the Reich government began to consider making Walter Simons a candidate for a broad alliance of republican parties on the same day. As before the first ballot, a candidacy by the provisional Reich President was rejected again.

Hindenburg as a candidate for the Reichsblock

It was clear to the right-wing politicians that Jarres had no chance under these circumstances. They had to find a more attractive candidate. The provisions of the electoral law suited them in this situation, because the electoral law allowed candidates to be nominated in the second ballot who had not stood for election in the first ballot. Different variants were discussed, including a prince of the Hohenzollern , Hans von Seeckt as head of the army command of the Reichswehr and the industrialists Gustav Krupp von Bohlen and Halbach and Fritz Thyssen . However, these options were discarded because they were all not considered sufficiently attractive.

Eventually, Paul von Hindenburg was considered. He had already been discussed as a candidate for the presidency of the Reich in 1920, but such considerations failed at the time. As the “Sieger von Tannenberg ” and as an exponent of the stab in the back legend , he also enjoyed a high reputation in the mid-1920s in national , conservative and monarchist- oriented sections of the population. However, Hindenburg initially rejected those who were now running for him. The 77-year-old non-party retiree was unwilling to be drawn into election campaigns and party affairs. He also gave health reasons for his refusal. Hindenburg stuck to his no for several days, although contacts from the Reichsblock visited him several times in his home town of Hanover . It was only when Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz , assisted by Walter von Keudell , made contact with the former field marshal on April 6, 1925 on behalf of the Reichsblock - which is now the joint umbrella of the DNVP, DVP, BVP, Bavarian Farmers' Union, Economic Party and German-Hanoverian Party , Hindenburg moved away from his categorical no. On the afternoon of April 8th, Hindenburg declared to the coordinator of the Reichsblock, Friedrich Wilhelm von Loebell, that he was ready to run. Tirpitz had successfully presented such a candidacy as a “national duty”. Not the parties despised by the former field marshal, but the fatherland calling the soldier. In contrast to 1920, the declared monarchist Hindenburg had no prior consultation with Wilhelm II, who was living in exile in Doorn in the Netherlands .

The DNVP and the representatives of large-scale agriculture in the East Elbe were able to credit themselves in particular to Hindenburg's selection . They hoped that if Hindenburg were elected they would have considerable influence on the state leadership, which they hoped to easily manipulate in their favor. Even Adolf Hitler ordered his party to vote for the aged Field Marshal so that its former employee Ludendorff, who on the first ballot, only 1.1 percent of the votes had been able to unite, did not run. The DVP and the big industrialists on the Rhine and Ruhr, on the other hand, had long stuck to Jarres because, in their opinion, the Duisburg mayor was more open to the wishes of industry than Hindenburg, in whom they saw an exponent of agricultural and military interests. When Jarres withdrew his own on the news of Hindenburg's candidacy, the spokesmen of the Rhenish-Westphalian entrepreneurs reluctantly swung into the Hindenburg camp, as did the DVP. In particular, its chairman Gustav Stresemann, as acting foreign minister, had concerns. An election by Hindenburg, who had originally been on the list of war criminals whose extradition the Versailles Treaty required, would be interpreted abroad as a sign of revanchism , militarism and monarchical restoration . All attempts at a policy of understanding with the victorious powers are endangered.

Foreign countries reacted as Stresemann had feared. The rejection in the press of the USA , France and Great Britain was so strong that Chancellor Hans Luther tried to prevent Hindenburg's candidacy after all. On April 24, 1925, he asked the provisional Reich President Simons to run in the second ballot if it were possible to persuade both Marx and Hindenburg to renounce their candidacies. Simons declined because he assumed that Hindenburg would stick to his decision.

Positions of BVP and KPD

The Reichsblock had overcome its candidate crisis. However, the new Reichsblock applicants threatened the Volksblock with considerable losses in the Catholic electorate. Because the Catholic BVP did not call for the election of the Rhenish Catholic Marx, but for the election of the Prussian Protestant Hindenburg. For them, Marx was too exposed to the influence of the SPD, which they viewed as their opponent. Losses among Catholics threatened the people's bloc not only in southeast Germany. Central politicians who were on the right wing of this party, such as Franz von Papen , also called for the election of Hindenburg for the same reason as the BVP: "If you want to pursue an anti-socialist policy tomorrow," said Papen, you couldn't " to put in the saddle today a center representative with millions of socialist voices ”. So it seemed realistic that conservative center voters in other regions would rather want the former field marshal. Strict opposition to social democracy and monarchist attitudes would make the difference for these voters, not religious affiliations.

Losses among conservative center voters could not simply be compensated for by gains on the left for the people's bloc, because the KPD stuck to Thälmann. Although he had no chance of winning and despite the contrary recommendation of the Executive Committee of the Communist International , he was to run again in the second ballot - that was the decision of the KPD headquarters of April 11, 1925. The Communists knew that with their decision they indirectly favored Hindenburg. The KPD publicly stated:

“It is not the job of the proletariat to choose the most skilful representative of the interests of the bourgeoisie, to choose the lesser evil between the civil dictator Marx and the military dictator Hindenburg. We call on the masses: Organize the mass struggle against the bourgeois dictators, against Hindenburg and Marx! [...] Every class-conscious worker votes against Hindenburg and Marx for Thälmann! "

Election campaign of the popular bloc

During the election campaign, the Volksblock and Reichsblock accentuated their different perspectives on the democratic present at the time. The people's bloc presented Marx as a man of the republic. In the official call of the SPD party executive on April 9, 1925, it said:

“The first battle is won. Now it is a matter of victoriously ending the campaign and ensuring success. Our first goal was to preserve and secure the republic! Our supreme law is to beat the monarchists! Therefore, everyone must unite for the second ballot. Our separation is the victory of the monarchist parties. Our agreement is their defeat. [...] The establishment of a Social Democrat would have made it difficult to gather all republican forces, would have improved the prospects of the monarchists. That is why the political necessity calls for the agreement of the three parties who jointly created the Weimar constitution, which sacrificed so many martyrs. "

The appeal subsequently emphasized that joining forces in the presidential election would only apply to the person of Marx, not to the politics of the center. Hindenburg was described as a stirrup holder by Ludendorff and a loyal subject to Wilhelm II. In addition, reference was made to the threat to peace and the horrors of the recent hyperinflation were recalled:

“Hindenburg's candidacy is a threat to peace! This election would bring immeasurable misfortune for the entire German people. The German currency is in danger again. Whoever chooses Hindenburg is voting for a new inflation. "

In the event of Hindenburg's election, it was feared that it would fall back into pre-Republican times. With him at the helm, Germany is threatened with renewed political self-isolation. "Anyone who works for Hindenburg is working to ensure that Germany should once again appear 'like a foreign body' in the world."

These fears were exacerbated by Kurt Tucholsky , who on April 17th saw the future of the Weimar Republic in black in the pacifist magazine Die Menschheit if the "imperial governor" was elected:

“Hindenburg is: Prussia. Hindenburg is: Back to the manor, away from the world, back to the barracks. Hindenburg means: crash with the whole world, well-founded distrust of foreign countries, especially France towards Germany. Hindenburg is: The Republic on Demand. Hindenburg means: war. One shouldn't just vote against him. One should also say what is and reject an attitude that has already brought about the spiritual downfall of the country. "

Election campaign of the Reichsblock

The other side suggested, however, that Marx was a prisoner of the social democracy, which was selling out Germany. In contrast to this, Hindenburg is an advocate of national interests and a “savior from discord”. Speakers who campaigned for Hindenburg emphasized the non-partisan character of his candidacy. In a text proposed by the Reichsblock for these speakers it said:

"Hindenburg is not a 'candidate' [...] nobody can and should 'bring him closer' to the German people. Hindenburg is Germany itself, is national self-confidence, longing and fulfillment at the same time. In a time of wavering decisions, unsteady unmanliness and resounding speeches, the name Hindenburg sounds almost like a fairy tale from the German sections [sic!] Of fame. "

The Reichsblock also tried to dispel all worries about the impending isolation of Germany. The day before the decisive ballot, Hindenburg spoke up with a radio address and emphasized "in front of the whole world" that he would do everything to keep new war threats away. Appealing to Prussian virtues , he stated:

“We will achieve this goal most surely when we show the other nations a picture of a people who have brought the hardship of the time together into true and intimate unity, the picture of a people who are determined to work and thrift in To stand together honestly and trust, to help one another, to bear the burdens to the best of our ability, to be united in our dedication to the big picture, not only to ask about rights, but first of all about duties. "

Result of the second ballot

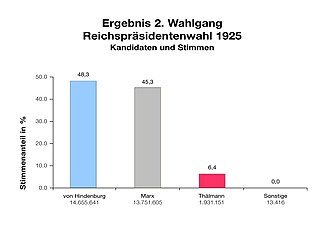

On April 26, 1925, Paul von Hindenburg won the second ballot with 48.3% of the vote, a lead of three percentage points over Marx. Thälmann drew around 60,000 more votes than in the first ballot, but still only achieved 6.4% of the votes cast.

The second ballot mobilized more voters than the first, and voter turnout rose by 8.7 percentage points to 77.6 percent. The Volksblock and Reichsblock benefited from this to different degrees. Marx outbid the total of all votes for the “Weimar” candidates in the first round of voting (Braun, Hellpach and Marx himself) by almost half a million. Hindenburg, however, got almost three million votes more than the three right-wing candidates in the first ballot - Jarres, Held and Ludendorff.

In addition to the different participation in the increased voter turnout, there were shifts between the Reich and Volksblocks, which contributed to Hindenburg's victory. In nine constituencies, the people's bloc failed to maintain the number of votes cast for the “Weimar” candidates in the first ballot. These constituencies, which developed in the opposite direction to the overall trend of the popular bloc, were predominantly Protestant. As expected, the largest increases for Hindenburg in the Catholic electorate occurred in Bavaria, although Marx did better than the people's bloc initially feared. He also received more votes than the “Weimar” candidates in the first ballot combined. The approval for Hindenburg was also very clear in the Catholic Upper Silesian constituency of Opole , although the right-wing candidates did well in the first ballot. The same was true for Catholic areas in East Prussia . With one exception ( Allenstein district ), Marx was always well ahead of Hindenburg. A considerable part of the Catholic electorate (depending on the municipality 31.6 to 40.0 percent) nevertheless voted for the “Sieger von Tannenberg”.

Hindenburg's incursion into the Catholic electorate was significant and decisive for his victory. Still, traditional Center voters mostly voted for the Republican candidate Marx. Even in classical areas of liberalism and in the social democratic strongholds, it was mostly Marx who won, not Hindenburg. Two peculiarities, however, contributed to Hindenburg's victory in these predominantly republican-electing regions: In Saxony , a considerable number of anti-clerical SPD voters preferred Thälmann or Hindenburg to the “Römling” Marx in the second ballot; Anti-Catholic liberals in Württemberg also refused to vote in large numbers and voted for the Reichsblock candidate.

Hindenburg himself accepted the election on April 29 and moved from Hanover to Berlin on May 11, 1925 . Thousands of his followers celebrated his arrival there with great enthusiasm. Paul Löbe swore him in on the Weimar Constitution in the Reichstag the following day. Hindenburg had previously confided to his friends that he had only now read the constitutional text for the first time and did not find it that bad. When reading the constitution, Hindenburg had worked with color markings familiar to him from his military service. He marked areas that concerned the Reich President with blue; He marked passages that referred to the Reich government or the Reichstag with the red pencil, which in the military always marked the enemy party.

Contemporary assessments

Communist comments

The Red Flag , the central organ of the KPD, interpreted the election result as a “symbol of the completion of the victory of the bourgeoisie ”. Since the days of the revolution, this has gradually regained power. A few days later a call from the executive branch of the Communist International was published in the same place. The criticism of the KPD's decision to let Thälmann run again in the second ballot was hardly concealed:

"In Germany there is a threat of monarchism [...] The communists cannot take the position that we are indifferent to the question: monarchy or bourgeois republic. The communists are not indifferent to this question, but put themselves at the forefront of the real struggle against the monarchist danger. "

Voices of the Reichsblock

Hindenburg supporters organized thanksgiving services. In provincial cities in particular, there were frequent parades and parades to celebrate the Hindenburg victory. Occasionally, in the wake of such rallies, there were attacks on well-known social democrats. Newspapers calling for his election welcomed the result. The German daily newspaper , politically close to the Reichslandbund , published an editorial under the heading: "Heil Hindenburg!". The conservative Kreuzzeitung noted:

“We no longer have an emperor, but the representative of the German people is no longer identical with the representative of the revolution in November 1918. Rather, there is a leader at the head of the empire who, having grown out of Prussian-German history, embodies it and preserving, pointing to a better future. "

Reactions in the people's bloc camp

The supporters of the popular bloc reacted differently. Theodor Wolff wrote in the morning edition of the Berliner Tageblatt on April 27, 1925:

“The Republicans have lost a battle, the previously monarchist Field Marshal von Hindenburg becomes President of the German Republic. Landbündler and officerbundler pop champagne stoppers today like after the murder of Rathenau . [...] What should one do with a people who have learned nothing from their misfortune and who let themselves be led by the same people by the halter strap again and again, even for the tenth or twelfth time? "

The liberal Frankfurter Zeitung lamented the, in their opinion, decisive share of the apolitical: "The romantic longing for past splendor and greatness, that has led these apolitical layers to the urn and Hindenburg to victory."

These voters did not recognize “that their personal and national misery was due solely to the old system of imperial government and warfare, as the representatives of which they venerated those generals.” The social democratic party organ Vorwärts blamed the KPD for Hindenburg's victory. The morning after the election, he headlined: “Hindenburg by Thälmann's grace!” At the same time, the SPD party newspaper spoke of a “surprise victory of the reaction , won by communist betrayal of the republic”.

disillusionment

A few months later, in mid-September 1925, the outcome of the presidential election was no longer seen as a bad omen. At the Heidelberg party congress of the SPD, the party executive explained to the delegates the political significance of the oath that the new Reich President had taken on the constitution of the republic. This act of swearing is an expression of the fact that "even in strictly conservative and military circles, the hope for the restoration of the monarchy is fading more and more [...]" The left-wing bourgeois magazine Das Tage-Buch also placed cautious hopes on this oath : It printed a caricature that From behind, Hindenburg raised his hand at the oath and put the mockingly cautious caption underneath: "Cut out and save seven years".

In the first few weeks after the election, Stresemann also had concerns about the new Reich President, but he remained Foreign Minister in the Luther government . After his initial hesitation, he changed his mind. Because Hindenburg had not pushed for a radical change of course in domestic and foreign policy, Stresemann gained confidence:

"[Hindenburg's] remarks on foreign policy and his earlier declarations breathed the spirit of that policy of understanding that can be the sole basis for the consolidation of European relations [...] Certainly, Hindenburg is a monarchist at home and does not think of the republic as the best theoretically To look at the form of government […] But the fact that he consciously puts himself at the service of this republic as one of the most distinguished representatives of the nation shows that there is no longer a 'Vendée' in our country who wanted to fight for the monarchy, but rather two There are groups of republicans that I would like to call the ideal republicans and the republicans of reason [...] If Hindenburg remains true to this line, and there is no reason to doubt it, then we will feel less than before about struggles for monarchy or republic, be exempt from coups and look forward to internal consolidation. "

Similar - with the exception of France - were the assessments abroad after a relatively short time. It now saw a force in the new Reich President who could guarantee foreign policy security.

The lack of elimination of democracy after Hindenburg's election as Reich President soon disillusioned the opponents of the republic from his circle of friends. The German national grand agrarian Elard von Oldenburg-Januschau stated in retrospect in his 1936 memoirs:

“In general I can say that my attempt to influence Hindenburg, true to my old line, aimed at the elimination of parliamentarism and the establishment of a dictatorship. These attempts were doomed to failure in the first few years. Only later, when developments had found their own way and the resolutions of the Reichstag were replaced by emergency ordinances, the first ice was broken. The field marshal shied away from further steps for a long time [...] "

Tirpitz was also quickly and lastingly disappointed by Hindenburg, because despite many attempts it initially failed to “frame” the new Reich President with an anti-republican advisory staff so thoroughly that the influence of moderate members of the government and top officials could have been neutralized.

Judgments of Politics and History

Causes of the election result

The Marxist-Leninist historiography of the GDR interpreted the election of Hindenburg as a “symptom of the right-wing development in Germany” and as a “clear expression of the resurgence of German imperialism and militarism.” The decision of the KPD leadership to run Thälmann again in the second ballot to let was criticized. Ultra-left and sectarian forces were responsible for this within the KPD.

Other reasons are given in earlier West German and present historiography. The historian Karl Dietrich Erdmann sums up the political causes of the election result in one sentence: "Hindenburg's victory is the result of the split in the labor movement and the split in political Catholicism." Heinrich August Winkler also draws attention to regional influences. Liberals in southwest Germany refused to vote for Marx, as did anti-clerical social democrats in Saxony.

Follow the election

"Stabilization"

With regard to the effect of this choice, differences in the judgments of non-Marxist scholars become apparent. In the minority are authors such as Ernst Rudolf Huber , who believe that the election and administration of Hindenburg would stabilize the republic. Huber attests that Hindenburg is bipartisan and impartial administration. Hindenburg also did not hesitate to hand over the Reich Chancellorship into social democratic hands. In December 1932 / January 1933 alone, Hindenburg had to be assigned responsibility for the failure of the stabilization of the republic. To relieve Hindenburg, Huber also argues that the party state-parliamentary system had already failed beforehand. This is a much more important reason for the failure of the Weimar Republic.

The American historian Walter H. Kaufmann attributes a similar effect to the election of Hindenburg. The initially high hopes that the monarchists had in his victory were quickly dashed, so that concepts for re-establishing a monarchy were abandoned. Opponents of the republic were introduced to the republic through Hindenburg's person and reputation. According to Kaufmann, Republicans also tended to regard the election of the former field marshal as the best thing that could have happened to the republic. The publicist Sebastian Haffner even declares the choice of Hindenburg to be a “stroke of luck”: This forced the reluctant groups from left and right to cooperate pragmatically and to mutual recognition. For the Weimar Republic this was “the only chance it ever had “Means. Such benevolent assessments, however, have not been able to establish themselves in research on the Weimar Republic.

"Conservative restructuring"

The presidential election of 1925 is mainly interpreted as a "severe defeat of the democratic republic" - as Eberhard Kolb put it . Ursula Büttner comments: “The Field Marshal General's victory over the Democratic candidate was a symbolic expression of how successfully the supporters of the old order had recovered from the shock of the revolution and how much the Republicans had been on the defensive since then.” Heinrich August Winkler, too considers Hindenburg's victory to be a “referendum against parliamentary democracy ”, as the Germans had experienced since 1919. He sees in their result a "conservative restructuring of the republic". Gotthard Jasper emphasizes the departure of the DVP and the BVP from the common front of parties loyal to the republic. Instead of black, red and gold, in 1925 they preferred black, white and red. According to Jasper, the decisive anti-Marxism of the BVP in particular signaled a serious crisis in the Weimar system. Hans Mommsen also emphasizes the anti-social-democratic resentment that was expressed in the election, but at the same time draws attention to the importance of the 3.5 million voters who only took part in the second ballot: of them, three million voted for Hindenburg. The republican parties would not have had access to this “dangerous arsenal of non-voters”, but the Reich Bloc with its anti-Marxist and nationalist election campaign did. Peter Longerich sees the election results as proof "that there was a majority alliance constellation to the right of the Weimar coalition, rooted above all in the Protestant middle-class middle-class and in the agrarian-conservative milieu." The voters who were motivated to vote for Hindenburg in 1925 by this alliance constellation , did not vote for the former field marshal in the next presidential election in 1932 , but for his competitor Adolf Hitler - this is shown by the election researcher Jürgen W. Falter .

The historian Peter Fritzsche points to changes that were observed in political culture during the election campaign for Hindenburg in 1925 . Partly independent of bourgeois parties, local associations and associations of the local bourgeoisie have mobilized to elect the Reichsblock candidate. This showed a bourgeois sense of community in front of the social democratic labor movement in particular. This bourgeois “we-feeling” was repeated in the following years on the occasion of Hindenburg's birthdays, which in this way resembled national summer carnival events or shooting festivals.

Overall, with Hindenburg's assumption of office, a “silent constitutional change” began, or a shift in weight to the right. According to this interpretation, the head of the state was now a man whose reputation came from pre-war and war times and who in this respect also embodied a different, pre-republican Germany. In addition, the social circles from which Hindenburg came - military and large-scale agriculture - again opened an exclusive door to the top of the state. A camarilla around the Reich President, also belonging to this milieu, gradually expanded the Reich President's office into a center of power that was directed against the Reichstag. From this position - according to Detlev Peukert -

"Henceforth open and covert attempts to shift the political axis of the republic to the right, to strengthen the elements of authoritarian governance and thus to create the conditions for a corresponding constitutional amendment in the medium term."

This quiet change did not only become apparent at the end of 1929, when the grand coalition under Hermann Müller was at the verge of its ability to act. It was already evident in the government crises towards the end of 1925 and 1926. Even in these situations, Hindenburg advocated governing “more to the right”. In concrete terms, this meant keeping social democrats away from government offices and involving the DNVP in government, if at all possible. Furthermore, in 1926, Hindenburg firmly and definitively rejected all considerations of restricting the possibilities of Article 48 of the constitution through an executive law. He did not want to see his control over the state of emergency curtailed. Another expression of the changed overall situation was Hindenburg's behavior in the conflict over the expropriation of the princes . He considered the planned expropriation without compensation to be unconstitutional and publicly rejected it. This increased the quorum for a success of the plebiscite as well as the necessary parliamentary majorities for imperial legal regulations on compensation for the prince. The referendum on expropriation ultimately failed, as did the planned imperial law on compensation for the princes.

Even if the political weights were to shift permanently in this way, according to the prevailing research opinion, this was not associated with an automatism that inevitably led to the end of the republic. The close outcome of the presidential election alone contradicted fatalistic expectations. The republic could still count on many republicans. It was above all dependent on the Reichstag and on cooperation across party lines whether the republic would be able to cope with its own problems and the burdens inherited from the empire.

literature

Sources and overview presentations

- Files of the Reich Chancellery , Weimar Republic. The Luther I and II Cabinets. January 15, 1925 to January 20, 1926. January 20, 1926 to May 17, 1926. Volume 1, January 1925 to October 20, 1926. Documents No. 1 to 170 , edited by Karl-Heinz Minuth. Boldt, Boppard am Rhein 1977, ISBN 3-7646-1649-0

- Andreas Dorpalen: Hindenburg in the history of the Weimar Republic , Leber, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1966.

- Jürgen W. Falter : The Two Hindenburg Elections of 1925 and 1932: A Total Reversal of Voter Coalitions , in: Central European History , 23 (1990) 2/3, pp. 225-241.

- Richard Freyh: Strengths and weaknesses of the Weimar Republic , in: Walter Tormin (Hrsg.): The Weimar Republic . 22nd ed., Unchanged. Reprint d. 13th ed. 1977, Fackelträger, Hannover 1977, pp. 137-187. ISBN 3-7716-2092-9

- History of the German labor movement. Vol. 4. From 1924 to January 1933. Edited by the Institute for Marxism-Leninism at the Central Committee of the SED, Dietz, Berlin (O) 1966.

- Sebastian Haffner : Notes on Hitler , Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1978, ISBN 3-596-23489-1

- Ernst Rudolf Huber : German constitutional history since 1789, Volume VII. Expansion, protection and fall of the Weimar Republic , Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, Berlin, Cologne, Mainz 1984, ISBN 3-17-008378-3

- Gotthard Jasper: The constitutional and power-political problems of the office of the Reich President in the Weimar Republic. The practice of the Reich Presidents Ebert and Hindenburg in comparison , in: Friedrich Ebert and his time. Balance sheet and perspectives of research , ed. by Rudolf König, Hartmut Soell and Hermann Weber on behalf of the Reichspräsident-Friedrich-Ebert-Gedenkstätte Foundation , Oldenbourg, Munich, 1990, pp. 147–159, ISBN 3-486-55811-0

- Walter H. Kaufmann: Monarchism in the Weimar Republic , Bookman Associates, New York 1953.

- Eberhard Kolb : The Weimar Republic , 2nd, through. u. supplementary edition, Oldenbourg, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-486-48912-7

- Peter Longerich : Germany 1918–1933. The Weimar Republic. Handbuch zur Geschichte , Torchträger, Hannover 1995, ISBN 3-7716-2208-5

- Werner Maser : Hindenburg. A political biography , Moewig, Rastatt 1989, ISBN 3-8118-1118-5

- Karl-Heinz Minuth : Introduction , in: Files of the Reich Chancellery , Weimar Republic. The Luther I and II Cabinets , […] Vol. 1, S. XIX-LXVI.

- Hans Mommsen : The playful freedom. The path of the republic from Weimar to its downfall. 1918 to 1933 , Propylaeen, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-549-05818-7

- Detlev Peukert : The Weimar Republic. Crisis year of classical modernism , Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-518-11282-1

- Wolfram Pyta : Hindenburg. Rule between Hohenzollern and Hitler , Siedler-Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-88680-865-6

- Wolfgang Ruge : Hindenburg. Portrait of a militarist , 3rd revised and expanded edition, VEB Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin (O) 1977

- Hagen Schulze : Weimar. Germany 1917–1933 (= The Germans and their Nation, Vol. 4), Siedler, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-88680-056-3

- John W. Wheeler-Bennett: The wooden titanium. Paul von Hindenburg , Wunderlich, Tübingen 1969.

- Heinrich August Winkler : Workers and the labor movement in the Weimar Republic. The appearance of normality. 1924–1930 , Dietz, Berlin / Bonn 1985, ISBN 3-8012-0094-9

- Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy , Beck, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-406-37646-0

- Heinrich August Winkler: The long way to the west, vol. 1: German history from the end of the Old Reich to the fall of the Weimar Republic , Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46001-1

Individual studies on the election of the Reich President in 1925

- Noel D. Cary: The making of the Reich President, 1925. German conservatism and the nomination of Paul von Hindenburg , in: Central European History , 23 (1990) 2/3, pp. 179-204.

- Peter Fritzsche: Presidential Victory and Popular Festivity in Weimar Germany: Hindenburg's 1925 Election , in: Central European History , 23 (1990) 2/3, pp. 205-224.

- Hanns-Jochen Hauss: The first popular election of the German Reich President. An examination of its constitutional foundations, its prehistory and its course with special consideration of the share of Bavaria and the Bavarian People's Party , Lassleben, Kallmünz 1965.

- Karl Holl: Confessionality, denominationalism and democratic republic - on some aspects of the presidential election of 1925 , in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 17th year (1969), pp. 254–275.

- Raffael Scheck: Courtly intrigue as a power strategy in the Weimar Republic. Paul v. Hindenburg's candidacy for the presidency of the Reich in 1925 , in: Eckart Conze, Monika Wienfort (ed.): Adel und Moderne. Germany in European comparison in the 19th and 20th centuries , Böhlau, Cologne, Weimar, Vienna 2004, pp. 107–118, ISBN 3-412-18603-1 .

attachment

Results in tabular form

| Candidate (party) | 1st ballot (March 29, 1925) |

2nd ballot (April 26, 1925) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paul von Hindenburg (Reichsblock) | - | - | 14,655,641 | 48.3% |

| Wilhelm Marx (1st flat in the center, 2nd flat in the Volksblock) | 3,887,734 | 14.5% | 13,751,605 | 45.3% |

| Ernst Thälmann (KPD) | 1,871,815 | 7.0% | 1,931,151 | 6.4% |

| Karl Jarres (Reichsblock) | 10,416,658 | 38.8% | - | - |

| Otto Braun (SPD) | 7,802,497 | 29.0% | - | - |

| Willy Hellpach (DDP) | 1,568,398 | 5.8% | - | - |

| Heinrich Held (BVP) | 1,007,450 | 3.7% | - | - |

| Erich Ludendorff (Völkische) | 285,793 | 1.1% | - | - |

| Others | 25,761 | 0.1% | 13,416 | 0.0% |

| Percentages relate to the number of valid votes cast. | ||||

| Eligible voters | 39.226.138 | 100.0% | 39,414,316 | 100.0% |

| Votes cast | 27,016,760 | 68.9% | 30,567,874 | 77.6% |

| Valid votes | 26.866.106 | 99.4% | 30,351,813 | 99.3% |

| Invalid votes | 150,654 | 0.6% | 216.061 | 0.7% |

Web links

- The election of the Reich President in 1925 Online contribution by the German Historical Museum .

- The presidential election in 1925 Exact result by numbers

- Election posters for the 1925 presidential election

Individual evidence

- ^ See Law on the Election of the Reich President (May 4, 1920) . With the "Second Law on the Election of the Reich President of March 13, 1925" (Reichsgesetzblatt, 1925, Part 1, No. 8, p. 19) it was changed at short notice. The aim of the changes was to ensure that the election process was as flawless as possible and at the same time not to let the number of applicants get out of hand. See Hanns-Jochen Hauss: Volkswahl , p. 47 f.

- ↑ In the justification for the electoral law formulated by Reich Interior Minister Erich Koch-Weser , it was stated that the parties should freely measure their strengths in the first ballot without consultation. If the absolute majority is missed in the first ballot, promising collective candidates could then be identified. The balance of power established in the first ballot is important, but - unlike in the runoff process - not the only decisive factor. The possibility of nominating new people as collective candidates increases the communication options. In this way, "the elected Reich President either receives the majority of all votes or at least a considerably larger fraction of all votes [...] than if the relative majority had decided in the 1st ballot." In this way, the Reich President is "more of a confidant of the People ”, because the voter is freer with this procedure than in runoff elections. As a rule, a second ballot can be expected, but this disadvantage can be accepted because the election only takes place every seven years. See Hanns-Jochen Hauss: Volkswahl , p. 30, note 10. There also the quotations from the reasons for the electoral law.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Minuth: Introduction , S. XLV.

- ^ See Act on the Deputy of the Reich President (March 10, 1925) .

- ^ On this, Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789, Volume VII , p. 545.

- ↑ See Eberhard Kolb: Weimarer Republik , p. 72 (quotation), 73.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Schein , p. 229, there also the quote. For the Magdeburg insult process, see also Heinrich August Winkler: Weg nach Westen , p. 456 and Eberhard Kolb: Weimarer Republik , p. 80.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789, Volume VII , p. 546 and Hanns-Jochen Hauss: Volkswahl , p. 63.

- ↑ On Geßler as a possible candidate, see John W. Wheeler-Bennett: Titan , p. 263 and in detail Hanns-Jochen Hauss: Volkswahl , p. 57–65 and Noel D Cary: Making , pp. 189–191.

- ^ Karl Holl: Konfessionalität , p. 255 and Noel D Cary: Making , p. 189.

- ^ Karl Holl: Konfessionalität , p. 255 f, Heinrich August Winkler: Schein , p. 238, note 110 and Hanns-Jochen Hauss: Volkswahl , p. 56 f.

- ↑ For the first ballot, the following personnel proposals for collective candidates from various party alliances were discussed: Paul von Hindenburg, Prince Bernhard von Bülow , Field Marshal August von Mackensen , Reich Chancellor Hans Luther, Ernst Scholz , Siegfried von Kardorff , Ex-Reich Interior Minister Rudolf Heinze , Wilhelm Freiherr von Gayl , Max Wallraf , Wilhelm Marx, Adam Stegerwald , Wilhelm Cuno . See Hanns-Jochen Hauss: Volkswahl , pp. 51–53.

- ↑ The overviews of the results for the presidential election always list seven applicants by name. The remainder are summarized under “Splintered” or “Other”.

- ↑ Comprehensive on this Noel D Cary: Making , p. 181 ff. Furthermore, Andreas Dorpalen: Hindenburg , p. 69 ff.

- ↑ a b Figures from the Statistisches Reichsamt (Hrsg.): Statistisches Jahrbuch 1926 , p. 450 f. The numbers can be found online at www.gonschior.de .

- ^ For an analysis of the results of the first ballot, see Heinrich August Winkler: Schein , p. 235 f.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Schein , p. 236, Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar , p. 279. See also Peter Longerich: Deutschland , p. 229.

- ↑ See Hanns-Jochen Hauss: Volkswahl , pp. 82-84 and the sources are the records of the two meetings with party leaders in the Reichstag building on April 3, 1925 (1 p.m. and 4 p.m.), in: Files of the Reich Chancellery, Weimar Republic. The Luther Cabinets I and II , Vol. 1, pp. 231–236.

- ^ See Law on the Election of the Reich President (May 4, 1920) .

- ↑ See John W. Wheeler-Bennett: Titan , p. 266.

- ↑ On this Wolfram Pyta: Hindenburg , pp. 443–451.

- ↑ To get in touch with Alfred von Tirpitz and the motives behind it, see in detail Raffael Scheck: Höfische Intrige . On the conflicts between DVP and DNVP after Hindenburg was contacted, see Andreas Dorpalen: Hindenburg , pp. 73-77. Also Wolfram Pyta on the events: Hindenburg , p. 467 f.

- ↑ See John W. Wheeler-Bennett: Titan , pp. 266-273.

- ↑ Paul von Hindenburg has publicly denied such contact with the former emperor (see the corresponding quote from Werner Maser: Hindenburg , p. 209). John W. Wheeler-Bennett: Titan , p. 272 is one of the few who follow the Field Marshal in this presentation. Wolfram Pyta, Hindenburg's biographer, also emphasizes that no contact was made in 1925, in contrast to 1920 (Wolfram Pyta: Hindenburg , p. 472 f and ibid, p. 448 f). For a long time in 1925, contact was considered certain. See, for example, Andreas Dorpalen: Hindenburg , p. 77 f; Heinrich August Winkler: Weg nach Westen , p. 459 and the same: Weimar , p. 280 f; Hans Mommsen: Verspielte Freiheit , p. 245; Werner Maser: Hindenburg , p. 203 and Raffael Scheck: Höfische Intrige , p. 113.

- ↑ Raffael Scheck: Höfische Intrige , p. 113.

- ↑ See Heinrich August Winkler: Schein , p. 237 and John W. Wheeler-Bennett: Titan , p. 268 f.

- ↑ See Heinrich August Winkler: Schein , p. 237 f, Karl-Heinz Minuth: Introduction , p. XLV as well as the record of State Secretary Kempner about a meeting between Luther and Simons on April 14, 1925 in the files of the Reich Chancellery, Weimar Republic. The Cabinets Luther I and II. , Vol. 1, pp. 243–245.

- ↑ On the attitude of the BVP see in particular Hanns-Jochen Hauss: Volkswahl . Historical electoral research has shown that this BVP recommendation for Hindenburg actually made a considerable contribution to Hindenburg's victory and Marx's defeat. See Jürgen W. Falter: Two Hindenburg Elections , p. 233 f.

- ↑ Quoted from Wolfgang Ruge: Hindenburg , p. 205. Other right-wing center politicians with a preference for Hindenburg were z. B. Theodor von Guérard and Clemens von Loe, see Karl Holl: Konfessionalität , p. 258.

- ↑ See Heinrich August Winkler: Schein , p. 238.

- ↑ Karl Holl: Konfessionalität , p. 256 and History of the German Workers' Movement , p. 76.

- ↑ Die Rote Fahne of April 12, 1925, quoted from Heinrich August Winkler: Schein , p. 238 f.

- ↑ On April 11, 1926, the forward wrote: “[...] vote on April 26 for the bloc of the republic! Vote for Wilhelm Marx! ". Quoted from Heinrich August Winkler: Schein , p. 239.

- ↑ a b Call for elections by the executive committee of the Social Democratic Party of Germany, printed in: Friedrich Purlitz / Sigfried H. Steinberg (ed.): Deutscher Geschichtskalender. Objectively arranged compilation of the most important domestic and international events . Vol. 41, vol. 1, January to June 1925. Leipzig 1925, p. 14.

- ↑ Vorwärts, No. 195 of April 25, 1925, quoted from Heinrich August Winkler: Schein , p. 239.

- ↑ Kurt Tucholsky, Collected Works in 10 Volumes, ed. v. Mary Gerold-Tucholsky and Fritz J. Raddatz , Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1975, vol. 4, p. 97.

- ↑ Hans Mommsen: Verspielte Freiheit , p. 245 and Andreas Dorpalen: Hindenburg , p. 79.

- ↑ So the formulation in the election call of the Reichsblock of April 8, 1925, quoted from Richard Freyh: strengths and weaknesses , p. 139.

- ↑ Quoted from Andreas Dorpalen: Hindenburg , p. 79, margin note there.

- ↑ Quoted from Heinrich August Winkler: Schein , p. 239 f.

- ↑ These were East Prussia, Pomerania , Liegnitz , Merseburg , Dresden - Bautzen , Leipzig , Chemnitz - Zwickau , Hamburg and Mecklenburg .

- ^ Numbers from Heinrich August Winkler: Schein , p. 242.

- ↑ Heinrich August Winkler: Weg nach Westen , p. 460. On the refusal of social democratic and liberal voter groups to Marx see also Karl Holl: Konfessionalität , p. 260 and 274 f.

- ↑ See also Peter Fritzsche: Presidential Victory , p. 222 and Wolfram Pyta: Hindenburg , p. 484 f.

- ↑ Hagen Schulze: Weimar , p. 297.

- ↑ Wolfram Pyta: Hindenburg, p. 486.

- ^ Die Rote Fahne, April 28, 1925, quoted from Wolfgang Ruge: Hindenburg , p. 208.

- ↑ Die Rote Fahne, April 29, 1925, quoted from Wolfgang Ruge: Hindenburg , p. 209.

- ↑ Werner Maser: Hindenburg , p. 210.

- ↑ See Peter Fritzsche: Presidential Victory , p. 215.

- ^ German daily newspaper of May 11, 1925; Kreuzzeitung of May 5, 1925, both quoted from Wolfgang Ruge: Hindenburg , p. 208.

- ↑ Frankfurter Zeitung, No. 309, April 27, 1925, quoted from Heinrich August Winkler Weimar , p. 282.

- ↑ Vorwärts, No. 196a, April 27, 1925, quoted from Heinrich August Winkler: Schein , p. 243.

- ↑ a b c Heinrich August Winkler: Weg nach Westen , p. 460.

- ↑ Quoted from Heinrich August Winkler: Schein , p. 245.

- ↑ Hagen Schulze: Weimar , p. 298.

- ^ Stresemann to the American ambassador in Berlin, Alanson B. Houghton, on June 4, 1925, quoted from Werner Maser: Hindenburg , p. 207.

- ↑ See Werner Maser: Hindenburg , p. 223.

- ↑ Quoted from Werner Maser: Hindenburg , p. 223.

- ↑ On this Raffael Scheck: Höfische Intrige , p. 114 f.

- ↑ History of the German Labor Movement , p. 76.

- ↑ Quoted from Eberhard Kolb: Weimarer Republik , p. 81. Similarly concise, Hagen Schulze: Weimar , p. 296: "But as it is, Hindenburg won with the help of Bavaria and the communists."

- ↑ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789, Volume VII , p. 549. Hindenburg was initially very reluctant to appoint Hermann Müller as Reich Chancellor, he would have preferred to see a DVP politician in this office (see Cabinet Müller II ).

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789, Volume VII , p. 549.

- ^ Walter H. Kaufmann: Monarchism , p. 232.

- ↑ Sebastian Haffner: Notes on Hitler , p. 71.

- ↑ Eberhard Kolb: Weimar Republic , p. 81. Hans Mommsen: Verspielte Freiheit , p. 247, also speaks of a “defeat of the republic”.

- ↑ Ursula Büttner: Weimar. The overwhelmed republic 1918–1933. Performance and failure in state, society, economy and culture , Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2008, p. 348 f, ISBN 978-3-608-94308-5 .

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weg nach Westen , p. 461.

- ↑ Gotthard Jasper: Problem , p. 157.

- ↑ Hans Mommsen: Verspielte Freiheit , p. 247.

- ^ Peter Longerich: Germany , p. 229.

- ^ Jürgen W. Falter: Two Hindenburg Elections .

- ^ Peter Fritzsche: Presidential Victory .

- ↑ So the formulations in Eberhard Kolb Weimar Republic , p. 81 and Heinrich August Winkler, Weg nach Westen , p. 461.

- ↑ a b Detlev Peukert: Weimar Republic , p. 212 f.

- ↑ Eberhard Kolb Weimar Republic , p. 82.

- ↑ Eberhard Kolb Weimarer Republik , p. 82 and Gotthard Jasper: Problematik , p. 158.

- ↑ See Detlev Peukert: Weimarer Republik , p. 212 and Freyh: strengths and weaknesses , p. 140.