Sophienkirche (Dresden)

The Sophienkirche was a Protestant sacred building not far from the Zwinger in Dresden . It was built in 1351 as the church of the Franciscan monastery and at the time it was demolished it was the only basic Gothic church in the city that was preserved. As a two-aisled church with two choirs that was built from the start, it deserves a special position in architectural history. The Sophienkirche was Dresden's evangelical court church until 1918 and thus the main church of the Lutheran Kingdom of Saxony. After the end of the monarchy, it was the seat of the Saxon regional bishop as the cathedral church of St. Sophia from 1922 .

The Sophienkirche had the earliest sculptural jewelry that can be found in the Dresden area. Two busts on consoles are also the first surviving pictorial representations of Dresden citizens.

The air raids on Dresden in 1945 severely damaged the Sophienkirche. Due to the lack of security measures, the vaults of the sacred building collapsed in 1946. In the years that followed, there were repeated controversies about how to deal with the church ruins, which ultimately became a political issue. Despite numerous protests, also beyond the borders of the GDR, the ruins of the Sophienkirche were torn down in 1962 and 1963 and a large restaurant was built in its place. Since the 1990s, the memory of the Sophienkirche has also been publicly maintained. The first construction work for a memorial began in 2009.

location

The Franciscans settled in Dresden in the 14th century in a "rather neglected place ... near the [western] city wall ", where they founded a monastery with a church. The Franciscan monastery church was located between the Wilschen city gate and the margravial castle . Behind the city wall, immediately west of the church, the main arm of the Kaitzbach flowed into the Elbe, not far to the north .

It was not until the construction of the Dresden Zwinger northwest of the church and the neighboring Taschenbergpalais to the northeast in the 18th century that "the exemption of the church and its effect on the surrounding areas" began. The main feature of the Sophienkirche was not its tower until its redesign in the late 19th century, but the high roof with three rows of dormers .

In 1811 the demolition of the city fortifications began. The city ditches were filled in and the open space southwest of the Sophienkirche was created as Wilsdruffer Platz . Sophienstrasse was laid out from Wilsdruffer Platz on the western front of the Sophienkirche to the Zwinger and Schloßplatz . The Kleine Brüdergasse to the north of the church and the Große Brüdergasse to the south of it flowed into it. Both streets were named after the monastery brothers and already existed in the 14th century.

A drawing from 1833 shows the location of the Sophienkirche at that time as seen from the castle tower . The castle can be seen in the foreground, behind it the Taschenbergpalais and the striking roof of the Sophienkirche. In the west, on the right in the picture, is the Zwinger, next to it the opera house at the Zwinger , which burned down in 1849 and which was built by Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann . It was later replaced by the Semperoper .

Through the renovation of the Sophienkirche with two striking towers by 1868, the sacred building entered "into dialogue with the other towers of the city" and became the central "focal point from the streets radiating from the Postplatz". The importance of the church in the urban context increased when the former Wilsdruffer Platz, renamed Postplatz in 1865, developed into a transport hub for the city. The palace hotel Weber , built in 1911, and the Dresden State Theater , built by 1913, complemented the urban ensemble of Sophienkirche-Zwinger-Schloss to the west. Before 1945, the Sophienkirche was enclosed in the north by the Taschenbergpalais and Dresden Castle, in the east and south by Baroque residential buildings and in the west by the Zwinger, the Weber Palace Hotel and the theater.

The old urban structure was completely destroyed in the bombing of Dresden and only partially restored after 1945 without the Sophienkirche. The reconstruction of the Zwinger was largely completed in 1963. The Taschenbergpalais was rebuilt by 1995. On the area of the Sophienkirche itself, the house at the Zwinger was built in 1998 and 1999 based on a design by the Austrian architect Heinz Tesar . The curved top of this elongated office building (popularly known as Advanta-Riegel ) ends at the former location of the northern tower of the Sophienkirche. To the south is the Wilsdruffer Kubus built in 2007/2008 .

History of construction and use

From the monastery church to the Sophienkirche

The Franciscan monastery in Dresden, first mentioned in 1272 , initially had a flat-roofed, single-nave hall church as a place of worship. It was around 44 meters long, 11.5 meters wide and around 17 meters high. In 1351, Margrave Frederick the Strict paid homage to the monastery by founding a new church. Four coats of arms in the church, which showed the Thuringian lion and the hen from Henneberg, refer to Friedrich the Strengen and his wife Katharina von Henneberg as donors. Investigations from 1962 to 1964, shortly before the church was demolished, showed that parts of the previous building were also used for the new building in 1351. The existing masonry on the west and north sides was retained and merely increased. Architectural historians put the date of origin of these oldest parts at "around 1250".

The new church building corresponded to the rules of the order and was kept unadorned. As a sermon church, the building had a hall-like, three-bay interior that allowed all believers to hear the sermon well. The church was built with two naves, with a choir formed from an octagon closing each nave. Both ships were the same height. Church construction "claims a special place in German architecture": Normally, single-aisle hall churches were only converted into a two-aisle structure by adding a second nave after a lack of space and some did not even have a choir. In 1400 the busmann chapel was built as an extension to the southern choir.

In 1421, builder Nicolaus Locher led the extension of the eastern part of the church by two bays. On July 14, 1421, the construction of the west gable began, in front of which a strong buttress made the inner division of the building clear. In the second half of the 15th century the interior of the church was vaulted, but this was "not done very skillfully"; the unevenness of the vault indicated a longer construction period.

After the introduction of the Reformation in Saxony, Duke Heinrich the Pious handed over the monastery and the monastery church to the City Council of Dresden in 1541, which, however, did not use the buildings. Heinrich's successor Moritz taught in 1544 at the monastery grounds and in the sacristy at the monastery Arsenal one. After the independent Dresden armory was built in 1563, the church rooms were used to store sea salt, grain and other provisions. The glass windows were removed and partially bricked up to protect the goods stored in the church from theft and the weather. Two grain floors were pulled in under the vaulted ceiling and wooden sheds were set up on the floor of the church. In addition, the monastery church housed a workshop for making wine vats for the court winery, which at the time earned the church the name Kuffenhaus .

The request of the city council formulated in 1555 to be allowed to use the monastery church again as a sacred building was not complied with by Elector August . Only when the old Frauenkirche and the old Kreuzkirche were no longer sufficient as burial places, a renewed application by the city council was granted in 1596; The elector's widow Sophie also ensured that the church service was resumed in 1598. In its application, the council only asked for the return of the "church with the two grain floors and the small courtyard [s] against the Große Brüdergasse to be cleared for a funeral for the noble and other noble court servants and citizens and to do ”and renounced the remaining monastery properties. After it was cleared, the city council took over the monastery church in June 1599, which had been severely damaged by years of unintended use and had to be repaired. The city council tried, through the mediation of court preacher Polycarp Leyser , to win Sophie von Brandenburg as a financier for the restoration, and in return offered the Electress to name the church after her:

“So that the Munich name Barfüssler Closter Church Abolished, the same after E. Churf. Gn. To be called Taufnahme zum Ewigen Gedechtnus zu Sanct Sophien. "

The request remained unanswered, so loans had to finance the repair of the church from 1599 to 1602. During the renovation, the church was raised by rubble and sand, numerous tombstones were removed and access to the grain floors was closed. At the time the church was being completed, repairs were also carried out on Dresden Castle , the chapel of which was therefore not available for the court service. The city council accepted a request from Elector Christian to use the former monastery church for the court service during this time. On June 24, 1602, Polycarp Leyser gave the first sermon in the church, which was consecrated as the "Church of St. Sophia". "With this designation, the honorary display was realized, which the council had already given the Electress widow in 1599, at the same time the name was chosen in a witty relation to the purpose of the church as a burial church." Elector Christian gave the name on June 22, 1602 approved by rescript .

The Sophienkirche under Sophie von Brandenburg

The court service took place again in the palace chapel in September. The city council's plan to hold regular church services did not work out. In the following years, the Sophienkirche served exclusively as a place for burials, which only the upper classes of the city could afford because of the burial costs of 50 thalers. In addition, a vault was built under the altar area in 1603 as a princely burial tomb. In 1632 Johann Wilhelm von Sachsen and 1635 Sophie von Pomerania found their final resting place in it.

The residents of Dresden wanted a church with public, general worship; Sophie von Brandenburg supported them in this. She contacted the city council, which gave her the church in exchange for compensation. The prerequisite was that the church continued to serve as a burial place.

The church was subordinate to Sophie von Brandenburg until 1610. During this time, she had the church structurally maintained from her resources. The most important foundation that Sophie von Brandenburg donated to the Sophienkirche was the so-called Nosseni Altar in 1606 , which remained the main altar of the Sophienkirche until 1945. In 1610, Sophie von Brandenburg returned the church and administration to the city council. At the same time, she donated 3,000 guilders, the interest of which was to provide church and school servants with additional income.

The Sophienkirche as a Protestant court church

Small structural changes were made to and around the church by 1737. In 1619 the churchyard, which adjoined the south and east sides of the church, was given a wall with candle arches . The vault of the church, which had been eaten away by years of salt storage, was repaired in 1625. From 1695 to 1699 the Sophienkirche got a new gallery for soldiers and persons of standing as well as a royal gallery. In 1696, the cloister behind the church, which still existed from the time of the monastery, gave way to a new sacristy. This was necessary because, in addition to the Sunday sermon allowed by the elector in 1611, a second sermon was allowed to take place in the church from 1693 and, due to the large number of visitors, there was an increasing lack of space for church equipment.

In 1737 the interior of the Dresden Palace was redesigned, including the rooms of the old palace chapel . New living space was created where the court preachers had held the Protestant service. In a rescript of May 29, 1737, Elector Friedrich August II ordered the superintendent Valentin Ernst Löscher and the city council that the court service should be relocated to the Sophienkirche immediately in order to ensure that the services went smoothly. At the same time the church equipment, regalia and the four bells on the castle tower were to be transferred to the Sophienkirche. Oberhofprediger Bernhard Walther Marperger held the first court service on June 16, 1737 in the Sophienkirche, which now had the status of a court church. From 1737 to 1923 it was also the home of the Protestant chapel boys . Due to its new status as a court church, the Sophienkirche was the most important Protestant church in the city of Dresden and the “main church of Lutheran Saxony”. It retained its status as a court church until the end of the Kingdom of Saxony in 1918.

Due to the new use, the church had to be structurally changed. As early as 1736, master carpenter George Bähr had delivered the design for a bell tower, the construction of which was directed by Johann Christoph Knöffel on the south front of the church in 1737. The construction was in the hands of George Bähr, master mason Johann Gottfried Fehre and master mason Johann Friedrich Lutz; the construction costs were 2536 thalers. A memorandum and coins were enclosed in the gilded tower button. On June 15, 1737, the castle chapel bells rang for the first time from the new tower of the Sophienkirche. The court officials attending the service needed a seat. The floor of the church, which until then had been covered with grave slabs of those buried after 1602, was covered with rubble and boards were laid over it. The provisional had to be renewed as early as 1773.

Also in 1737 the so-called Golden Gate , which had previously formed the entrance to the castle chapel in the large castle courtyard, was moved to the porch of the west facade of the Sophienkirche. It was considered "one of the finest works of the early Renaissance in Saxony".

In the second half of the 18th century there were problems with the church roof. As early as 1755, the covering of the church roof had been half interrupted due to the Seven Years' War , so that the weather in the uncovered part of the church caused damage and parts of the attic floor became rotten. To make matters worse, in 1597 the court had reserved the right to continue to use the church's attic as a “courtyard and fodder floor for pouring the court grain”. The weight of the grain put additional strain on the roof structure; the grain could only be removed after the elector had waived his rights in 1778 in return for compensation.

Further construction work mainly concerned the windows. The Gothic tracery was removed and the slugs replaced by simple glass windows that let more light into the church. In addition, the interior of the church was painted white. In 1794, the churchyard wall was raised because the noise of the riders and carriages on the Große Brüdergasse increasingly disrupted the service. From 1794 to 1824 the Sophienkirchhof was secularized .

Renovations in the 19th century

Interior remodeling in 1834

In 1834 the interior of the Sophienkirche was fundamentally renovated. The aim was to make the church, which still looked gloomy after the first changes to the window glazing, even brighter and thus friendlier. For this purpose, a new window opening was broken through next to the pulpit and the window above the pulpit was enlarged. The inner doors received panes of glass, the interior walls got gilding and a light oil painting, stone green the walls and light stone green the vaulted ceiling. The pillars were painted in white-gray and the galleries in white with bronze strips. The stalls received a veined oak brown paint.

The church also got a new entrance from the kennel side. Instead, the Freiberg family's prayer rooms disappeared. The pews were placed more loosely, the space around the Nosseni altar was expanded and provided with steps. More space was created by removing numerous epitaphs and other works of art. The epitaph-like, sweeping frames of the paintings by clergymen in the Sophienkirche were replaced by modern frames. The Nosseni epitaph attached to the first pillar in the western nave found its new place under the western gallery . The figure of Mater Dolorosa crowning the pulpit gave way to a simple gold cross. The rededication of the Sophienkirche after the interior renovation took place on November 24, 1834.

Exterior and interior remodeling from 1864 to 1875

Twenty years after the interior remodeling, the exterior of the church was also considered out of date. Above all, the neighboring Zwinger , which was completely renovated after a fire in 1849 , made the Sophienkirche appear all the more in need of renovation. The massive brick gable on the west side and extensions around the Golden Gate were particularly criticized. On June 15, 1854, the Council of Dresden, headed by Mayor Friedrich Wilhelm Pfotenhauer , decided to put the facing of the gable and a new portal to tender. The proposals should be based on the style of the Dresden Zwinger as well as the Golden Gate, which should be retained. At the same time, the city council pointed out that "if the situation is good, in the future two towers corresponding to the gable building can be placed on the flanks of the portal building without the need for partial demolition of the building now to be built if this eventuality occurs." In the invitation to tender, the council offered a fee of 100 thalers or, alternatively, construction would be carried out.

The academic council rejected the design by the architect Sommer, which the city council had approved. He called for the church to be rebuilt without recourse to elements added in the post-Gothic period, such as the Golden Gate. In addition to Ernst Giese and Bernhard Schreiber , the council also entrusted Christian Friedrich Arnold , who had already made a name for himself with designs for church buildings in the (neo) Gothic style, with plans for the renovation . Arnold proposed a two-tower project in which the original Gothic church should be preserved, but completely re-clad so that the Gothic walls were not visible from the outside. On May 3, 1864, the “Royal Commission for Local Building Matters” approved Arnold's design, which Arnold was to implement as an architect.

The exterior renovations lasted from 1864 to 1868. Among other things, the church tower was demolished and the Golden Gate removed. The west facade received two side stair towers 66.22 meters high with filigree pierced spiers. Between the towers was a porch with two portals. Arnold opened partially blocked windows and added new ones that illuminated the church more evenly than before. The Gothic tracery was removed and replaced by uniform tracery windows. The removed tracery was used to backfill the soil.

Yellow Postelwitz sandstone was used for new two-dimensional components, while white Cotta sandstone divided the building. Except for figurative additions made by the Rietschel students Friedrich Wilhelm Schwenk (1830–1871) and Georg Kietz (1824–1908), the west gable remained relatively unadorned. The north side was redesigned in 1867 and the south and east sides in the following year. In addition, the church got a new slate roof.

Inside, Arnold removed more heraldic stones and epitaphs. In 1875 the church pores were redesigned; the organ was moved from the gallery in the south choir to the north west gallery. At the same time, the bus man's band was renewed and the intermediate floor, which had previously served as the organ's bellows chamber, was removed. The church received a new pulpit and gas lighting as well as painting in the neo-Gothic style. The portraits of the pastors that had hung on the walls in the nave were placed in the sacristies and side aisles. The Nosseni epitaph was moved to the Busmann Chapel. The total cost of the renovation of the Sophienkirche amounted to 457,794 marks. In 1900 Cornelius Gurlitt wrote regretfully that the renovation of the Church of St. Sophia from 1864 "mostly deprived it of the characteristic details", so "the outer surfaces [...] were completely barricaded and coated with cement, the profiles and dimensions were uniformly designed so that only a few features of the historical building development have been preserved ”.

The Sophienkirche until 1945

As early as 1907 there were plans to equip the church with new choir stalls, to enlarge the altar space and to renew the wooden floor. Work began in December 1909 with the removal of the wooden floor. The ground under the beam bearing and the rubble layer was covered with grave slabs from the 17th century, with tombs sometimes lying four times on top of each other. The construction workers found tombs made of loose bricks without mortar that had collapsed, so that individual grave slabs had fallen into the open tombs. It was particularly critical that tombs were lower than the adjacent pillars and walls. For example, the gallery pillars stood over collapsed tombs, so they had no lower support. The Sophienkirche was in danger of collapsing, so the interior of the church had to be completely renovated. The corresponding building permit is dated July 10, 1910, and Hans Erlwein received the order to carry out the work. He had the damaged foundations of the church restored by filling in the tombs, then leveling the ground and covering it with a layer of concrete. The tombs and valuables had previously been removed from the tombs. The city council sold parts of the jewelry.

During the excavations, construction workers found a black, coffin-like box in a crypt in the north choir of the church. It contained various relics : fragments of a cross made of rock crystal, vessels and vials that were partially filled with earth and oil, a tooth set in gold, a silver cross that is said to contain a splinter of the cross of Christ, two ostrich eggs with faded sayings, two coconuts and a host with the resurrection of Christ. In the box there were also twelve small mother-of-pearl discs with scenes from the Passion of Christ. It is considered likely that in the course of the dissolution of the monastery from 1539 the monks hid the relics in the church, which thus escaped confiscation by the city council of Dresden. Only the metal frames of the relics are missing. The reliquary is kept in the Dresden City Museum.

A central heating system connected to the district heating plant replaced a previous system from 1858 in 1910. The church received new chairs, gray marble slabs covered the enlarged altar space. Groundwater infiltration resulted in the abandonment of the crypt under the altar area and its new construction under part of the south choir and the busman's chapel, through which access was possible. Hans Erlwein designed the crypt, the painter Paul Rößler decorated it with Christian symbols and inscriptions. In the new crypt, the sarcophagi from the old crypt have been re-erected.

The southern choir was initially built up. The resulting space was used as a silver chamber and was uncovered in 1910 so that the church "regained an essential element of its spatial effect". The Nosseni epitaph came back into the nave from the Busmann Chapel and found its location on the first pillar not far from the Nosseni altar. The grave slabs found were let into the walls of the church at ground level and the portraits of the court preachers were hung on the pulpit wall and above the galleries. The church was painted white, with the stalls, organ and galleries in dark brown with gold decorations. Grape-shaped bronze candlesticks created by Karl Groß (1869–1934) illuminated the sacred building. The church was consecrated on October 31, 1910.

The year 1918 marked the end of the monarchy in Saxony and with it the end of the Sophienkirche as a court church. The city of Dresden transferred it to the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Saxony . This elevated the Sophienkirche to the cathedral church of St. Sophien. From 1922 it was the place of activity of the first Saxon regional bishop Ludwig Ihmels as the episcopal church . Major construction work was carried out in 1932 on the spiers, which had proven to be very sensitive to the weather and had to give way to copper-covered helmets.

Destruction and demolition 1945 to 1962

Destruction in 1945 and collapse in 1946

During the bombing of Dresden on the night of February 13-14, 1945, the Sophienkirche burned down completely. It was one of 27 bombed churches in the city. Remains of important works of art, including the portraits of court preachers and other movable works of art, were removed from the church in June 1945 and taken to the Green Vault , the preserved boiler room of the Frauenkirche, the city museum and the Annenkirche . Individual parts were moved to the Museum of Medieval Art on Albrechtsburg Castle in Meißen . Securing the Sophienkirche ruin was not possible in 1945 due to the financial and material hardship of the church's monument preservation. The first winter continued to affect the sandstone of the ruin, so that the vaults and pillars of the Sophienkirche collapsed on February 28, 1946. The recovery of the works of art had been completed only three days earlier; valuable gravestones were walled in.

“The surrounding walls, both towers, the tombs, parts of the equipment and the helmet of the south tower have been preserved. The result was a large, column-free church space, the closed wall sections of which in the years to come fueled the imagination of architects and monument preservers to consider various possible uses. "

Surrender of the ruins in 1951

In July 1948 the bells were recovered from the towers of the church and handed over to the Emmauskirche in Kaditz and the Mickten chapel . After thefts in the church and in the crypt, workers walled up the ruins in 1949. While the church was still included in urban planning until 1949, it was then increasingly available in construction plans. The city assessed the reconstruction of the church as possible, but criticized the lack of a purpose. In agreement with the monument conservator Hans Nadler , a representative of the Evangelical Lutheran State Office stated in 1949 that the financial outlay for the reconstruction did not correspond to the historical value of the church, since “almost nothing of the old, original structure has been preserved”. The church leadership therefore decided at their meeting on August 2, 1949 not to keep the ruins. The Wettiner coffins were transferred to Freiberg Cathedral in August 1950 and sculptures were transferred to the Dresden City Museum in 1951. On August 11, 1950, the preserved south spire of the Sophienkirche was blown up because sheet copper was needed to cover the Dresden Kreuzkirche . However, the blast destroyed a large part of the copper material.

When the church was supposed to disappear during the clearing of large areas of Dresden city center in early 1951, Hans Nadler turned to the city and the state church office of Saxony and explained the historical value of the building in detail. Because of its art-historical importance, those responsible took the ruins from the major clearing of the Postplatz in 1951 out. Nevertheless, the regional church office decided in 1951 to abandon the ruins to decay. There were two main reasons for this: Since the Sophienkirche had a personal community without its own parish, which also practically no longer existed after the end of the war, it was not urgent to build it as a church. Since all of the inner-city churches in Dresden were badly damaged or destroyed, a selection was inevitable for the construction, if only for financial reasons: "The repair of the Sophienkirche alone would have swallowed up all the funds for the church's reconstruction for several years."

Monument status from 1952

In March 1952, the architect Arno Kiesling compiled a list of endangered cultural monuments on behalf of the city's building department, for the reconstruction of which costs were determined; Among the 39 objects there was also the Sophienkirche. The administration for arts affairs of the Saxon state government determined for these buildings that they “must be preserved” provided they “do not collide with the new city map”. On June 26, 1952, the status of the church as a monument was confirmed by the Ordinance for the Protection of National Cultural Monuments.

Various plans followed on how to preserve the church, including designs without a tower ( Heinrich Sulze , 1954) or with tower stumps and a cross between them ( Fritz Steudtner , 1956). Usage plans ranged from church use for church services and concerts to use as an (open-air) museum.

Of fundamental importance for the fate of the Sophienkirche was the replacement of the building of the National Tradition in favor of industrialization, especially in housing construction, and the resolution of the 5th SED Party Congress in 1958 to remove the most visible traces of war in the city centers by 1962 and to rebuild the city center to be completed by 1965 - later postponed until 1970. In Dresden a decision had to be made about the future of the remaining inner city ruins of the Dresden Residenzschloss with Georgentor , the Taschenbergpalais , the Frauenkirche and the Sophienkirche. At the 4th meeting of the Dresden SED's city council on September 18, 1958, Dresden's mayor Walter Weidauer stated the intentions with regard to the preservation or demolition of the ruins:

“We have to hold discussions about housing, new streets, houses of socialist culture , etc. We should not and must not allow ourselves to be pushed away by the united opposition. We must not allow ourselves to be forced into a discussion about the structure of the Frauenkirche, the Sophienkirche or the Schloss, but rather, in particular, throw down all the strength of the party to whatever new is happening; H. in the discussion we are having, the new socialist thinking must come first. "

For the first time it came up that Dresden needed a large restaurant.

Demolition plans from 1958 and demolition 1962–1963

On October 15, 1958, the city council, the highest decision-making and executive body of the city of Dresden, approved a proposal on the perspective of building the city of Dresden by 1965 at the 21st council meeting . He decided to preserve the Frauenkirchruine, the Taschenbergpalais and the castle and planned the demolition of the Sophienkirche, as this was "not decisive for the character of Dresden". A department store was to be built in their place.

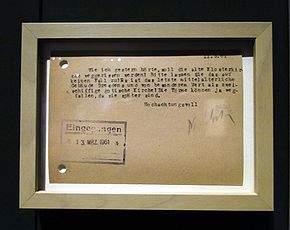

In 1951 the regional church office decided to leave the ruins to their own devices, but now, in view of the impending demolition, they stepped up to preserve the only medieval building in Dresden. After an article about the fate of the Sophienkirche was published in May 1959 in the magazine Deutsche Architektur , West German newspapers such as the FAZ and the Hamburger Abendblatt reported on the decision to tear it down at the beginning of June . On June 11, 1959, an article in the Sächsische Zeitung informed the Dresden public about the decision. In addition to monument conservationists such as Fritz Löffler , Heinrich Magirius and Hans Nadler, well-known architects, including Leopold Wiel and Heinrich Rettig , turned against the demolition of the church . The state church office was able to prevent the church from being demolished, which was to be initiated in July 1959 following an urgent decision, by sending official protest notes to Otto Grotewohl and Johannes Dieckmann , among others . Pastor Karl-Ludwig Hoch described the planned demolition of the church in 1960 in a protest letter to Lord Mayor Herbert Gute as "culturally hostile barbarism". In 1961, the city council and the SED city administration decided to build a large restaurant instead of a department store. The demolition of the church was held fast. In a statement on the rebuilding of the city center, it was also said: “Gothic architecture is not typical for Dresden.” The pressure on those responsible for the city increased when Walter Ulbricht personally removed the Sophienkirche from a model of the city center during a visit to the city in 1961 and “his amazement about it ... expressed that the ruin had not yet disappeared. ”In order to ensure that valuable architectural parts could be recovered, those responsible decided in April 1961 to demolish the church instead of blowing it up. On June 26, 1962, the regional church received the information that the property of the Sophienkirche had been declared the "development area" of the planned large restaurant.

The demolition of the church began in July 1962 with the removal of the side extensions that were attached during Arnold's reconstruction. There were protests at the Institute for the Preservation of Monuments, the Kupferstichkabinett and members of the TH Dresden who, among other things , threw leaflets from the tower of the Dresden Catholic Court Church with the text "Save the Sophienkirche before it's too late!" A resolution of the Council of Ministers of June 14, 1962 stated that the construction of the center of destroyed cities should not be completed until 1970 and that "historically valuable buildings [...] must be secured so that they can be rebuilt in due course without loss of substance." The district and city management of the SED disregarded the decision and in August 1962 confirmed the demolition of the Sophienkirche as well as the Güntzbad , the Reformed Church , the lodge house on Ostra-Allee and the orangery on the Duchess Garden . In October the demolition of the church had progressed so far that apart from the towers and the busmann's chapel only the original hall building from the 13th century remained. Monument preservers recovered 23 tombstones, the altars, keystones, ribs and other valuable parts of the church. In addition, the Gothic tracery used to backfill the soil in 1864 was recovered and later stored in the Zion Church Lapidarium . In December 1962, the towers were torn down and the side walls were demolished, with the exception of part of the north wall, which was removed on May 1, 1963. Then the area was greened and a parking lot was created.

Dealing with the memory of the Sophienkirche from 1964 until today

From 1964 to 1967 the large restaurant "Am Zwinger" was built in place of the Sophienkirche . During the excavation for the foundations, large parts of the southern crypts of the Sophienkirche, which had been preserved, were destroyed and the partly incompletely decomposed bodies were removed together with rubble. Only after four days of construction did the Institute for Monument Preservation receive permission to examine the 70 or so grave chambers and secure valuable grave goods, some of which were 300 years old. The large restaurant, popularly known as Fresswürfel , was an eyesore after the fall of the Wall and the peaceful revolution . It was partially demolished in 1998 and completely removed in 2007.

Other crypts were disrupted in 1966 when cables were laid to the Kulturpalast . The gold and silver jewelry found during the excavations went to the city museum , where thieves stole it in 1977. Research by ZDF in 2009 revealed that the Ministry for State Security may have ordered the theft of the so-called " Sophia treasure ". Only in 1999 did 38 parts of the grave goods reappear in Oslo. Another 17 pieces, including the golden king's chain, have been lost.

In 1998 archaeologists uncovered parts of the north wall and the rows of prayer rooms from 1864 and examined them. The reason was the imminent construction of the Haus am Zwinger office block , which was built on part of the grounds of the Sophienkirche until 1999. Since 1999 a memorial plaque designed by the Dresden artist Einhart Grotegut (* 1953) has been commemorating the Sophienkirche at the level of the former main portal. The society for the promotion of a memorial for the Sophienkirche Dresden e. V. had commissioned them. The plaque bears the inscription "Sophienkirche in memoriam" and lists historical data next to a picture of the western front of the church. It rests on three original sandstone columns from the Sophienkirche. Since 2000, red granite paving stones have been tracing the floor plan of the Sophienkirche on the floor.

The Dresden city council decided in 1994 to erect a memorial for the Sophienkirche. In the architectural competition, a design by the architects Gustavs und Lungwitz prevailed, which provides for a replica of the busmann's band at the original location. A glass cube is intended to enclose the chapel, "to illustrate the connection between the Busmann Chapel and the Sophienkirche, the buttresses of the Franciscan Church will be erected as stylized steles", according to the design of the architects' office. Construction work on the Busmann Chapel Memorial began in 2009.

Furnishing

altar

In 1487, the so-called Clare Altar was named as the only altar. The daily mass donated by Abbess Beatrix von Seusslitz was read there. The Klara altar still existed around 1602 when Christof Müller narrowed it by one cubit.

The Nosseni Altar goes back to a foundation from Sophies von Brandenburg in 1606. It was created until 1607 under Giovanni Maria Nosseni in the northern choir of the Sophienkirche. The sculptors involved in the execution were probably the brothers Sebastian Walther and Christoph Walther IV . For the altar, which cost 3,500 guilders , various stone materials were used that came from quarries developed and managed by Nosseni. Unusually there are no references to the founder on the altar, such as a portrait or the coat of arms. That is why experts see the foundation today as a kind of "thank you and faith testimony" of Sophie von Brandenburg.

The Nosseni Altar was badly damaged in the bombing of Dresden and parts of it were recovered from the collapse of the vaults in 1946. The altar structure was first walled up in the ruin and recovered shortly before the church was demolished in 1963. From 1998 to 2002 the reconstruction of the altar, which is now in the Loschwitz church , took place.

Pulpit, stalls and galleries

The original pulpit had a Mater Dolorosa on the sound cover, which in 1834 gave way to a simple, gilded cross. The pulpit was rebuilt in 1875. It was made of serpentine and sandstone and was decorated with the figures of Peter and Paul, as well as Matthew and John. The sound cover was made of oak. The previous pulpit was no longer available in 1900.

Around 1600 the Sophienkirche was furnished with "special council stalls". New stalls were made for the nave in 1737 with special seats for the court officials. After the construction work in the nave in 1910, the Sophienkirche received new stalls, which were painted deep brown.

The carpenter David Fleischer probably built the galleries from 1600 to 1602. They were supported by stone pedestals under the wooden pillars. Gallery conversions took place from 1692 to 1693. Between 1695 and 1699 the church was given a new gallery for soldiers and notables, as well as a royal gallery. In 1738 the galleries were expanded and rebuilt during the interior renovation in 1875.

Baptismal font

The sandstone baptismal font by the sculptor Hans Walther II from 1558 was moved from the palace chapel, which was secularized in the same year, to the Sophienkirche and placed in the Busmann chapel . Colored stones, including jasper , various types of marble and serpentine, have been decorating the baptismal font since 1602, which may not have been decorated with columns on the chalice until this time. In 1606 the font is said to have been changed again. He, too, suffered severe damage in the bombing of Dresden in February 1945. The reconstruction from numerous fragments took place in 1988 and 1989 by the Dresden sculptor's workshop Hempel and the State Office for the Preservation of Monuments in Saxony . The fragmentary font is now in the State Office for the Preservation of Monuments of Saxony in Dresden.

It is 115 centimeters high and has a maximum diameter of 88 centimeters. Four pilasters connected by arches divide the foot. In the arches there are putti in mourning clothes. The belly of the chalice-like baptismal font is divided into four double hermen , between which there are flower garlands with putti and birds. Above it is a continuous row of diamond blocks in different types of marble.

The chalice is divided four times by two Ionic columns, between which there were both serpentine niches and four gilded alabaster reliefs . They showed the flood with Noah's ark , the walk through the Red Sea , the baptism of Jesus and the blessing of children . While the baptismal font is made of red marble, the baptismal lid was decorated with lions' grimaces , tendrils and a meandering edge made of wood. The baptismal lid, which carried the resting lamb of God as a gilded end , has not been preserved. Gurlitt saw the foot, relief and baptismal lid as Walther's work, while he classified the other parts as additions from the period after 1600.

Church decorations

Gallery boards

In 1625, the Dresden painters Zacharias Wagner († 1658), father of the writer and draftsman Zacharias Wagner , and Sigmundt Bergk created a total of 18 gallery panels with associated writing panels depicting events from the life of Jesus. Both painters were commissioned with the entire cycle of paintings. According to the invoices received, Wagner and Bergk were jointly responsible for twelve paintings and text panels, six other paintings and text panels come exclusively from Bergk. The pictures have different dimensions, different painting techniques and styles as well as different types of wood.

The paintings were in the galleries of the church until the interior renovation of the Sophienkirche in 1875. Up to this time they had been painted over several times, for example during the renovation of the church in 1834. However, precise information on the arrangement of the pictures is missing. A single watercolor showing the inside of the Sophienkirche around 1820 is considered lost and only depicts parts of the galleries, with the parapets of the upper galleries being empty. In the lower gallery, square writing fields alternate with wider painting fields, so that it can be assumed that the paintings were attached to the first gallery. The exact order is not known, however; Nor is it known what the gallery arrangement of the Sophienkirche looked like around 1625. Ornamental paintings under a gallery painting, however, at least allow the certainty that parts of the paintings were made on site on already painted gallery panels.

Some panels were bullet damaged during the May fights in 1849, others were broken. The wooden gallery panels initially came into the possession of the Dresden History and Topography Association. As early as 1881 six of the original 18 tablets were missing, while all panel paintings were preserved. In 1891 they were transferred to the collection of the Dresden City Museum, which presented the panels, among other things, in an exhibition in the Dresden City Hall in 1910. The pictures were restored several times in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but this is hardly documented. After 1945 the panels remained in the museum's depot. Their condition deteriorated more and more until the restoration from 2004 to 2009. The gallery panels are among the few remaining parts of the pictorial equipment of the Sophienkirche.

Nine of the 18 picture panels have been preserved. Around 1900 there were still twelve of the associated tablets, the text of which came from Georg Hausmann , the then rector of the Dresden Kreuzschule . Five still exist today.

Tombs and epitaphs

The Sophienkirche was already a burial place as a monastery church until 1540, the oldest known graves came from the year 1400. In the course of the renovation of the church from 1599 to 1602, the notary Stephan Hanemann made a list of the existing mortuary stones on June 14, 1599. The painter Daniel Bretschneider and the carpenter David Fleischer made drawings of them and numbered them. At that time, 73 tombstones were recorded in the church, some of which reappeared during construction in 1910. Other tombstones were broken and used as material for church steps or to mend paths outside the church. After the tombstones had been recorded, the floor of the church was covered with rubble.

After its consecration in 1602, the Sophienkirche served again as a burial church. The tradition of designating the lying grave sites with standing grave monuments goes back to the Middle Ages. In 1709, the Kirchner Gottlob Oettrich recorded in his work the correct directory of those who had died, along with their monuments and epitaphs, which found their rest in the local church of St. Sophia, etc., all of the grave monuments and memorial images in the church since 1602. He registered 132 lying epitaphs, 71 hanging flags and shields as well as 28 inscriptions and epitaphs in the Sophienkirchhof. When it was dedicated as a Protestant court church in 1737, the church floor was filled with the grave slabs of those who had been buried since 1602. It was covered with a layer of rubble and a joist and wooden floor were installed over it. Even after 1737, families could still have deceased relatives buried in acquired tombs. The last burial took place on June 29, 1802. While the church and ancillary rooms were available to the upper class for burial, the choir area was reserved for the Princely House. The large royal crypt was built under the altar and was later relocated.

The epitaphs on the walls listed by Oettrich, including inscription panels, reliefs in metal and stone, paintings, statues, weapons, armor, mourning flags and heraldic shields, were preserved until 1834 and were partially removed when the interior of the church was renovated. During the renovation from 1864 to 1868 and during later repair work, many epitaphs were destroyed, including all weapons, armor and flags. Some epitaphs were outsourced to the city museum, so that by 1910 only a few were preserved in the church, including the Nosseni epitaph, the epitaph created by Wolf Ernst Brohn in 1652 by Duchess Sophie Hedwig and parts of an epitaph that were used for the neo-Gothic sacristy altar .

During excavations in the nave in 1910, the workers found tombs that were partially laid out in four ways. The tombstones were salvaged and partially placed in the church space, and the tombs filled. After the bombing in 1945, some of the tombstones were relocated. Today they are in the Dresden Kreuzkirche, in the State Office for the Preservation of Monuments, in the Dresden City Museum as well as in other churches in Dresden and in various depots. The sacristy altar of the Sophienkirche is today in the Friedenskirche in Dresden- Löbtau .

Only a few tombs and epitaphs of prominent personalities have survived, including the slab of the grave of Polycarp Leyser , parts of the Nosseni epitaph by Giovanni Maria Nosseni and the memorial tablet by Jakob Weller . The grave (memorials) of Johann Christian Bucke , Gregor Heimburg , Heinrich Pipping , Caspar von Schönberg , Andreas von Schönberg , Matthias Hoë von Hoënegg and Gottlob Friedrich Seligmann were destroyed. Some of the coffins of the members of the Saxon royal family buried in the princely crypt are now in Freiberg Cathedral .

In contrast to the stone epitaphs, of which more than two dozen could be relocated and thus partially partially preserved, only two wooden epitaphs of the Sophienkirche have been preserved. Below is the epitaph by Otto Christoph and Polixena Elisabeth von Teuffel, which shows the Passion of Christ on 16 carved linden wood panels. It is kept in the Dresden City Museum.

Grave goods

As early as 1910, the around 60 open tombs in the church were emptied during work. The valuables found, including bracelets, necklaces, chains of orders and rings, but also statues of Christ or crucifixes and a prayer book were brought to the city museum. Some pieces were bought by private individuals.

Other crypts were destroyed during construction in 1964. Emergency salvage rescued further grave goods from the roughly 70 graves that were on display when the city museum reopened in 1966. In 1977, strangers stole 57 items of jewelery from the city museum during opening times, including numerous grave goods from the crypts of the Sophienkirche. The first part of a chain was found in 1986, a further 38 objects appeared in Oslo in 1999 and returned to the museum in 2005. Another pendant on a chain was identified in Hanover in 2002 and returned to the museum in 2006. 17 objects are still missing.

The Dresden City Museum has over 100 pieces of jewelry and valuables from the crypts of the Sophienkirche, including bracelets and collars, buttons, crucifixes, rings, chains and pendants. In addition to order and society chains from around 1600, the museum also owns everyday objects such as toiletries, as well as weapons and items of clothing from the graves. A woman's garment, reconstructed in 1990, dates from around 1630; a children's dress from the 17th century was recovered in 1964 and reconstructed in 1987.

Busman band

The Busmann Chapel was built around 1400 as an extension on the southeast side of the Sophienkirche and served the founding Busmann family as a family and burial chapel. After the Reformation, the chapel was initially a food store and temporarily the entrance hall of the church. Probably from 1737 onwards, the chief preacher used the Busmann chapel as a sacristy where baptisms took place.

The Busmannkapelle had an altar with the representation of the Holy Sepulcher until 1552. Together with consoles, which show the donors Lorenz Busmann and Ms. Busmann, among others, it was one of the earliest sculptural jewelery that has been documented in the Dresden area. While the altar was destroyed in 1945, several console busts have been preserved and are in the Dresden City Museum. After the castle chapel was dissolved in 1737, the Busmann Chapel received its altar and baptismal font. Both suffered severe damage during the bombing of Dresden in 1945 and relocations in the following years and are now being stored, partially reconstructed, in the State Office for the Preservation of Monuments in Saxony. Remnants of the Busmann Chapel flow into the building of the Busmann Chapel Memorial or are to be exhibited there.

organ

Repairs to the first organ of the church, among other things, have been handed down from 1487 ; So it is said of the organ master, "dy organ has neither made that ande naw mere bellows ". In 1624 1023 guilders were spent on a new organ that organ builder Tobias Weller is said to have made. Repairs to the instrument dragged on until 1640.

From 1720 to 1721 Gottfried Silbermann created the new organ for the Sophienkirche. It was the first that Silbermann built for a house of worship in Dresden. The organ prospectus may have been made by George Bähr, a draft of which has survived. Around 1773 Johann Gottfried Hildebrandt carried out repairs to the organ. Further repairs were carried out by Johann Andreas Uthe in 1813 and 1816. From 1874 to 1875, Carl Eduard Jehmlich overhauled the organ.

The Silbermann organ was initially located on the gallery by the south choir of the church, with a ceiling in the Busmann chapel that served as the organ's bellows chamber. In 1875 the organ was moved to the west side of the north aisle, whereby the prospectus was retained. In 1945 the instrument was completely destroyed.

Concerts by Johann Sebastian Bach on the organ in 1725 and 1747 are known. His son Wilhelm Friedemann Bach was the organist of the Sophienkirche from 1733 to 1746.

Disposition of the Silbermann organ:

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Remarks

- ↑ Coming from the Glauchau Silbermann organ, installed in 1836, replaced by shelf 8 ′ in 1936.

- ↑ Made in 1747 by Johann George and David Schubert, replaced in 1875 by Octavbaß 8 ′, Octavbaß 4 ′ and Aeoline 8 ′.

Bells

It is said from 1486 that the monastery church at that time received a new bell. Heinrich Kannengießer poured them for free. Since the mendicant orders were not allowed to have bell towers with full bells, it found its place in the roof turret. In 1677 Andreas Herold cast a medium and a large bell for the Dresden Palace Chapel . Together with two other bells from the castle chapel, they were attached to the newly built bell tower of the Sophienkirche in 1737. During Arnold's renovation, the Sophienkirche received two bell towers, in which the bells were set up as early as 1866. There were three bells from the old castle chapel, which were dated to 1677. A fourth bell added to the ringing in 1868.

In 1940 the bells of the Sophienkirche were prepared for delivery as Reichsmetall donation . An inventory on April 23, 1940 counted four bronze bells, the largest on the north tower and three more on the south tower. The smallest of the bells in the south tower was no longer part of the peal and came from the pre-Reformation period. Presumably it was the bell that was cast in 1486.

However, the bells remained in the belfry until the church was bombed, where they survived the destruction of the church. The bells were dismantled in 1948. The large bell in the north tower and a middle bell in the south tower were transferred to the Emmaus Church in Kaditz . Both bells have been preserved and were restored in Nördlingen from 2006 to 2007. The Mickten chapel received the small bell from 1486, which is located in the roof turret of the chapel on Homiliusstrasse, which has been redesigned as a parish hall and is no longer functional.

The fourth bell mentioned in 1940 was missing when it was dismantled in 1948. It is not known whether it was destroyed in the bombing of the church or whether it was the only bell that was delivered to the Sophienkirche in 1940.

| image | Surname | Chime | year | Dimensions | size | Inscription and jewelry | Receipt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Little bell | c sharp 3 | 1486 (?) | 35 kilograms | 37 centimeters high, lower diameter 41.5 centimeters | anno domini. milesimo. ProzLXXX | from the south tower, in the roof turret of the Mickten parish hall |

|

Medium bell | a 1 | 1677 | 400 kilograms | bottom diameter 88 centimeters | AB ELECTORE IOHANNE GEORGIO SECUNDO ARX JSTA INSTAVRATA INSIGNITER / TURRIS FACTA ALTIOR NOLAEGUE HAE SUSPENSAE DUCES VIVAT RUTA SAXENIA; IGII.HZSICVBC / MDCLXXVII. (Front); GOSS ME ANDREAS HEROLD (back); Electoral Saxon and another coat of arms | from the south tower, bells of the Emmauskirche Kaditz |

|

Big bell | f sharp 1 | 1677 | 750 kilograms | lower diameter 109 centimeters | AB ELECTORE IOHANNE GEORGIO SECUNDO ARX JSTA INSTAVRATA INSIGNITER / TURRIS FACTA ALTIOR NOLAEGUE HAE SUSPENSAE DUCES VIVAT RUTA SAXENIA; IGII.HZSICVBC / MDCLXXVII. (Front); GOSS ME ANDREAS HEROLD (back); Electoral Saxon and another coat of arms | from the north tower, bells of the Emmauskirche Kaditz |

| - | Medium bell | c sharp 2 | 1868 | ? | lower diameter 71 centimeters, inner height 50 centimeters | Cast by Johann Gotthelf Große KS piece caster in Dresden Cis No 504; But whoever does not have the Spirit of Christ is not his (obverse under a Christ head); Love never ends (back under the communion cup on the open Bible) | from the south tower, whereabouts after 1940 unknown |

Sophienkirchhof

The Sophienkirchhof was built in 1602 instead of the monastery stable to the east and south of the church. It was right by the old churchyard of the Franciscan monastery. From 1619 a wall surrounded it on the south and east side, on which several arched candle arches were built.

While the church was considered the burial place of the nobility, mainly citizens found their resting place in the Sophienkirchhof. One of the prominent buried in the churchyard was probably Christoph Kormart . The last burial in the churchyard took place in 1740. At the request of the elector, the demolition of the 36 remaining burial grounds began in 1794 and was completed in 1824. In the same year the churchyard wall to the Große Brüdergasse and the Quergässchen was torn down.

literature

- Robert Bruck : The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912.

- Dehio Handbook of German Art Monuments: Dresden . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich and Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-422-03110-3 , p. 30.

- Wiebke Fastenrath: To the former bus man band in Dresden . In: State Office for the Preservation of Monuments (ed.): Preservation of monuments in Saxony. Notices from the State Office for Monument Preservation Saxony . State Office for Monument Preservation, Dresden 1996, pp. 5–15.

- Cornelius Gurlitt : Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony . Volume 21: City of Dresden, part 1. In commission at CC Meinhold & Söhne, Dresden 1900.

- Jürgen Helfricht : Dresden and its churches . Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-374-02261-8 , pp. 121–124.

- Ch. Ch. Hohlfeldt: The Sophienkirche in Dresden . In: The collector for history and antiquity, art and nature in the Elbthale . No. 13, Dresden 1837, pp. 193-199.

- Markus Hunecke: The Sophienkirche in the course of history. Franciscan traces in Dresden . benno, Leipzig 1999, ISBN 3-7462-1309-6 .

- Matthias Lerm : Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, ISBN 3-356-00876-5 .

- Fritz Löffler : Console figures in the Busmann Chapel of the former Franciscan Church in Dresden . In: Journal of the German Association for Art History . Volume XXII, Issue 3/4, Berlin 1968, pp. 139–147.

- Georg Müller: The Franciscan Monastery in Dresden . In: Contributions to the Saxon church history . Issue 5, 1890.

- Heinrich Moritz Neubert : On the history of the Sophienkirche in Dresden, particularly with regard to its legal position . Dresden 1881 ( digitized version )

- Gisbert Porstmann, Johannes Schmidt (Hrsg.): Sermon in pictures. A rediscovered cycle of paintings from the Dresden Sophienkirche . Municipal Gallery, Dresden 2009, ISBN 978-3-941843-02-8 .

- Otto Richter : The gallery paintings from the Sophienkirche . In: Dresden history sheets . Volume 18, number 2, Dresden 1909, pp. 35–36.

Web links

- Website of the Busmann Chapel Memorial

- Contributions about the Busmannkapelle , Gesellschaft Historischer Neumarkt Dresden

Individual evidence

- ^ Georg Müller: The Franciscan Monastery in Dresden . In: Contributions to the Saxon church history . Volume 5, 1890, p. 94.

- ↑ Wolfgang Hehle: The urban development around the Sophienkirche in Dresden . In: State Office for the Preservation of Monuments (ed.): Preservation of monuments in Saxony. Notices from the State Office for Monument Preservation Saxony . Number 1. State Office for Monument Preservation, Dresden 1993, p. 45.

- ↑ Wolfgang Hehle: The urban development around the Sophienkirche in Dresden . In: State Office for the Preservation of Monuments (ed.): Preservation of monuments in Saxony. Notices from the State Office for Monument Preservation Saxony . Number 1. State Office for Monument Preservation, Dresden 1993, p. 50.

- ↑ a b Rudolf Zießler: Dresden. Franciscan monastery church . In: Monuments in Saxony . Boehlau, Weimar 1978, p. 389.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 4.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 10.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 11.

- ↑ Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony . Volume 21: City of Dresden, Part 1. In Commission at CC Meinhold & Söhne, Dresden 1900, p. 90.

- ↑ Quoted from Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 12.

- ↑ Quoted from Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 13.

- ^ A b Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 13.

- ^ A b Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 14.

- ^ A b Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 17.

- ^ Jürgen Helfricht: Dresden and its churches . Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2005, p. 122.

- ↑ a b c Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony . Volume 21: City of Dresden, Part 1. In Commission at CC Meinhold & Söhne, Dresden 1900, p. 91.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 19.

- ^ A b Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 25.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 27.

- ^ Text of the announcement of the city council, quoted in after Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 29.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 33.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 35.

- ↑ Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony . Volume 21: City of Dresden, Part 1. In Commission at CC Meinhold & Söhne, Dresden 1900, p. 80.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 37.

- ↑ Markus Hunecke: The Sophienkirche in the course of history. Franciscan traces in Dresden . benno, Leipzig 1999, p. 119.

- ^ Jürgen Helfricht: Dresden and its churches. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2005, p. 123.

- ↑ Markus Hunecke: The Sophienkirche in the course of history. Franciscan traces in Dresden . benno, Leipzig 1999, p. 117.

- ^ Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 39.

- ^ Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 55.

- ^ Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 69.

- ↑ Representative of the Evangelical Lutheran State Office Kandler on August 1, 1949. Quoted from Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 83.

- ^ Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 85.

- ^ Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 126.

- ^ Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 116.

- ^ Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 286, FN 13.

- ^ Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 166.

- ^ Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 174.

- ^ Quoted from Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 184.

- ↑ Architect Kurt Liebknecht (1905–1994) 1958. Quoted from Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 190.

- ^ Quoted from Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 202.

- ↑ Helmut Laskowsky to Werner Krolikowski, February 13, 1961. Quoted from Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 206.

- ↑ conversation memo ; quoted after Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 208.

- ^ Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 225.

- ^ Quoted from Matthias Lerm: Farewell to old Dresden . Hinstorff, Rostock 2000, p. 228.

- ↑ Peter Redlich: "Eating cubes" - partial demolition starts . In: Sächsische Zeitung , June 30, 1998.

- ↑ See press information on the Terra X broadcast: Sophienschatz secret files on presseportal.de

- ↑ Bettina Klemm: Crypts of the Sophienkirche are disappearing again . In: Sächsische Zeitung , October 5, 1998, p. 9.

- ↑ Quoted from busmannkapelle.de

- ↑ Markus Hunecke: The Sophienkirche in the course of history. Franciscan traces in Dresden . benno, Leipzig 1999, p. 37.

- ↑ This concerned the “red marble for the columns, black marble for the backsheet, dark green Zöblitzer serpentine for the column bases, plus light alabaster” for reliefs and ornaments. See Walter Hentschel: Nosseni and the third Walther generation . In: Walter Hentschel: Dresden sculptors of the 16th and 17th centuries . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 1966, pp. 67–88, here p. 69.

- ^ Heinrich Magirius: The Nosseni altar from the Sophienkirche in Dresden . Publishing house of the Saxon Academy of Sciences, Leipzig 2004, p. 16.

- ↑ Markus Hunecke: The Sophienkirche in the course of history. Franciscan traces in Dresden . benno, Leipzig 1999, p. 103.

- ↑ Markus Hunecke: The Sophienkirche in the course of history. Franciscan traces in Dresden . benno, Leipzig 1999, p. 113.

- ↑ Markus Hunecke: The Sophienkirche in the course of history. Franciscan traces in Dresden . benno, Leipzig 1999, p. 104.

- ↑ According to Gurlitt. Bruck called the clothing monk's robes. Cf. Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 23.

- ↑ Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony . Volume 21: City of Dresden, Part 1. In Commission at CC Meinhold & Söhne, Dresden 1900, p. 152.

- ↑ Other sources give his name differently than written in the church accounts as Bergt . Cf. Otto Richter: The gallery paintings from the Sophienkirche . In: Dresden history sheets . Volume 18, number 2, Dresden 1909, p. 36.

- ^ Gisbert Porstmann, Johannes Schmidt (Ed.): Sermon in pictures. A rediscovered cycle of paintings from the Dresden Sophienkirche . Städtische Galerie, Dresden 2009 pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Markus Hunecke: The Sophienkirche in the course of history. Franciscan traces in Dresden . benno, Leipzig 1999, p. 144.

- ↑ Otto Richter: The gallery painting from the Sophienkirche . In: Dresden history sheets . Volume 18, number 2, Dresden 1909, p. 35.

- ↑ Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony . Volume 21: City of Dresden, Part 1. In Commission at CC Meinhold & Söhne, Dresden 1900, p. 96.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 40.

- ↑ Information according to information on display boards in the Dresden City Museum.

- ↑ Quoted from Georg Müller: The Franciscan Monastery in Dresden. In: Contributions to the Saxon church history. Volume 5, 1890, p. 96.

- ^ Georg Müller: The Franciscan Monastery in Dresden . In: Contributions to the Saxon church history . Volume 5, 1890, p. 96.

- ↑ a b Markus Hunecke: The Sophienkirche in the course of history. Franciscan traces in Dresden . benno, Leipzig 1999, p. 37.

- ↑ Information on the missing bell according to Bruck, p. 34.

- ^ Folke Stimmel, Reinhardt Eigenwill et al .: Stadtlexikon Dresden . Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1994, p. 392.

- ^ Kormart, Christoph . In: Norbert Weiss, Jens Wonneberger: Poets, thinkers, literati from six centuries in Dresden . Die Scheune, Dresden 1997, p. 106.

Coordinates: 51 ° 3 ′ 5.7 " N , 13 ° 44 ′ 4.5" E