Little owl

| Little owl | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Little Owl ( Athene noctua ) |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||

| Athene noctua | ||||||||||

| ( Scopoli , 1769) |

The little owl ( Athene noctua ) is a small, short-tailed owl species from the family of real owls (Strigidae). The distribution area of the little owl extends over Eurasia and North Africa. It is a characteristic inhabitant of the tree-steppe with sparse or low vegetation and prefers to hunt on the ground. Once chosen, he usually occupies a territory for several years and sometimes even for life.

The little owl was already considered a bird of wisdom in ancient Greece and was a symbol of the goddess Athena . This is also referred to by the scientific name, which translated means 'night Athena'. That is why the phrase carrying owls to Athens refers to the little owl or its depiction on ancient drachma coins. In the German-speaking world, the name “little owl” indicates that this species of owl not only breeds in tree hollows, but also in stone barns, chapels and wine cellars. In Central Europe, the little owl population has been falling sharply for several decades. The main cause of this decline is the destruction of habitats that provide the little owl with suitable environmental conditions.

In 1972 the little owl was bird of the year in Germany. In Switzerland he was voted Bird of the Year for 2021 .

Surname

The bird species used to be, but is still sometimes regionally called owl or owl or owl, although other smaller owl species end in "owl", such as B. the tawny owl or the great gray owl . The word Kauz occurs exclusively in the German language and has been documented as a bird name since the 15th century. It has been known as an epithet for people in Hesse since the 14th century and is still used today to describe a strange person in expressions such as "comic owl", which can be seen as a comparison to the bird's withdrawn way of life. The naming of the bird species is traced back to the sound- imitating Indo-European root * gō̌u-, * gū- "call, scream", that is, to the scream audible in the dark, which is also the primary motif for the word "owl". There are also attempts to explain folk etymology , for example, that the term comes from the cat, namely due to the similarity of words, the similar face, the sharp vision at night and the hunt for mice. However, such folk etymologies are generally rejected in linguistics today.

description

Adult little owls

The little owl reaches a body size of 21 to 23 centimeters. The wingspan is between 53 and 58 centimeters. The size corresponds to that of a song thrush , but the little owl looks larger than this due to its loose plumage and broad, rounded head. Feather ears are missing and the low forehead makes the little owl look flat-headed. There is no noticeable gender dimorphism . The weight of the males varies between 160 and 240 grams, that of the females between 170 and 250 grams. Adult birds reach their maximum weight in December and January. They are easiest in June and July.

The facial veil is only weakly developed in the little owl and is limited at the top by whitish stripes over the eyes. The eyes are lemon to sulfur yellow. The dark, sepia-brown upper side of the body has whitish creamy yellow or gray-white drop spots and transverse bands, the spots on the top of the head being particularly dense, small and stripe-shaped and on the front back larger and more rounded. The little owl has a conspicuous, white V-shaped mark on the neck that converges with a white neck band and surrounds darker parts of the plumage (so-called occipital face ). Cream-colored to beige-brown spots form five to six cross bands on the wings of the hand. Two to three such cross bars are usually visible on the arm wings. On the other hand, the pattern of stains on the arm covers varies greatly. The under wing coverts, on the other hand, are light and have gray to blackish spots. The throat is whitish and delimited from the chest by a beige or rust-brown collar. The underside of the body is yellowish white with sepia-brown, irregular longitudinal stripes. On the breast plumage in particular, these longitudinal spots are very dense and wide, so that they only let the basic color stand out a little. The legs are feathered whitish and the toes are covered with bristle-like feathers.

Adult little owls begin their annual moult with the fledgling of the young birds. The large feathered moult lasts 98 to 115 days and is completed in Central Europe towards the end of October and beginning of November.

Nestlings and young birds

The down dress of newly hatched stone owls is white, dense and short. Their hatching weight is only between 10 and 12 grams. Apart from the back of the running joint, the legs are covered up to the toes. The wax skin is initially pink, the beak and claws are whitish or grayish pink. The wax skin changes color to a dark purple-gray within the first week of life. The beak initially changes color to a bluish gray with a yellow tip and then becomes increasingly olive yellow. The claws, however, turn black. The eyes open from the 8th to 10th day of life.

The first signs of the gray-brownish nestling dress ( mesoptile ) appear from the 5th day of life. It first appears on the shoulders and arm covers, later on the back of the head, neck, in the middle of the back and on the chest and thighs. The development of the mesoptile is completed on the 21st day of life. The typical markings can be seen on the face. The breast plumage is roughly longitudinally spotted to striped. There are striking rows of white polka dots on the covers of the hands and shoulders. The large plumage is fully developed around the 40th day of life. In Central Europe, the mesoptile is replaced by youth clothing from August to November. This youth dress is similar to the adult annual dress, but is a bit paler and more rusty brown. The spots are creamy yellow to rusty brown and are less contrasting. The spots on the top of the head and on the fore back are even less noticeable than in adult birds. Young little owls show their first age dress shortly after they are one year old.

behavior

The little owl covers short distances in a straight rowing flight, while over long distances a woodpecker-like wave flight is characteristic. Hunting stone owls also show jolting and gliding flights . Little owls usually fly just above the surface of the ground. In the case of little owls that fly up from a higher vantage point and then rear up again, this creates a U-shaped flight path. Before taking off from a control room, they often show an excitement-induced pedaling at the seat. Since the body weight is high in relation to the wing surfaces and the flight feathers are relatively short and hard, unlike the extremely nocturnal owl species, the flight of the little owl is not silent and can be heard from close by. A purposefully used wing clap, as occurs in the long-eared owl , the rabbit and the barnacle owl , is missing.

Little owls often move around on the ground. They are able to run so fast that they can catch up with a fleeing field mouse. They then run with very long-legged steps and occasionally switch on shorter jumps, while when moving more slowly, they tend to trip in short steps. Little owls can often be seen free-sitting on chimneys, fence posts, boulders, wires or masts during the day. Dormant little owls often fluff their plumage loosely and pull in their flat head so that they appear spherical. In light rain they spread their wings wide and bristle their plumage. Occasionally they can be seen sunbathing. The wings are opened limply, the plumage is puffed up and the face is turned towards the sun. An approaching person is often fixed by the little owl with brief jerky head movements. Similar to enemy encounters, the little owl often shows what is known as a vertical kink, in which the owl crouches into an almost horizontal posture and then straightens up with his heels stretched out.

voice

Little owls have a very extensive repertoire of sounds, ranging from barking, snoring, meowing sounds to sonorous, soft calls. The singing of the male consists of nasal, dark and noticeably rising guhg , guuig or gwuäig calls, each lasting less than a second and ending abruptly with a shrill miju or meow . Males repeat these calls, which humans can still hear at a distance of 600 meters, 12 to 20 times per minute. The vocal repertoire also includes very stretched long syllables with a fluting glissando , which can be onomatopoeically described as gluui or goojahüi . Especially unmated males also sing during the day. Occasionally a similar song can be heard from females. With them, however, the calls are less pure and rarely consist of more than five guhg syllables.

When excited , both sexes call out a piercing, loud meowing or short yapping kwiu or kwie , which can increase to a piercing kja . Occasionally this can be heard in a cheeky episode. Rivals sitting close to each other cheekily and pearly, which is reminiscent of a soft chatter. Hissing and hoarse-dry voice feeling and begging calls are particularly noticeable in the duet of the partners. Soft, rising and questioning-sounding uu , guu or guip calls are also performed in a duet by the partners and serve to synchronize the partners before the prey is handed over, mated and cave shows.

Young birds already have a large part of the sound repertoire in their nestling age. In the first week of life, the young birds call a soft guh or gjuu , which is reminiscent of the attractiveness of the adult birds. They hoarsely call srii or chrii until they are four weeks old . From the fourth week of life, older nestlings increasingly let out a snoring chch , which is reminiscent of the contact calls of young barn owls . Like many other owls, little owls that feel disturbed can hear a loud squeak of beak , which is generated by quickly striking the upper and lower beak . Nestlings let this instrumental sound be heard particularly often.

distribution

In addition to a limited southern foothills in the Ethiopian region, the little owl is distributed across the Palearctic . The main distribution area is between 22 ° and 51 ° N. The northern distribution limit corresponds approximately to the 17 ° C July isotherm, the southern approximately that of 31 ° C.

In a west-east direction, the distribution area extends from the Atlantic coast of Great Britain to the Korean Peninsula and northeast China. The northern limit of distribution runs through Belgium , Holland , Denmark , Latvia , the region of Pskow and Moscow and Meschtschora . Little owls occur in this region to the north of 56 ° N. In the Ural Mountains, 54 ° N and in Kazakhstan, 49 ° N, are the northern limit of distribution. In an easterly direction, the distribution limit continues along the Altai and the Tannu-ola Mountains , through the southwest of Dauria and the northeast of Mongolia.

Little owls are found throughout the Mediterranean . In western Africa their range even exceeds 22 ° N in a southerly direction. They also colonize the north and northeast of Africa, parts of the Arabian Peninsula , the south of Sudan and the north of Somalia . In Asia , the southern limit of distribution runs through northeastern Pakistan , southern Tibet . In central and eastern China, 35 ° N is the southern limit of distribution.

In New Zealand the species was naturalized in the Otago region between 1906 and 1910 . The aim was to regulate the number of introduced European songbirds, some of which spread very widely there. This turned out to be a failure, since songbirds only have a small share in the prey spectrum of the little owl. The little owl is now widespread across the entire South Island .

Inventory development

Basically, the populations in Central and Western Europe have declined due to habitat loss, so that the species is sometimes very rare in these countries. In contrast, the little owl is a widespread to common species in the Mediterranean area and in large parts of its Asian distribution area. The assumptions for the global population vary widely. Dries Nieuwenhuyse, Jean-Claude Génot and David H. Johnson assume in their little owl monograph for the year 2004 of 235,000 to almost 650,000 breeding pairs worldwide. BirdLife International , on the other hand, estimated the worldwide breeding population at 556,000 to 1,267,900 breeding pairs for the same year.

In Great Britain the little owl was a rare wanderer until the second half of the 19th century. The owl was only deliberately settled in the 1870s and 80s. Already at the turn of the 20th century there were two large breeding populations in the south-east of England and in the east of the Midlands . Increased by further settlements, little owls populated most of the British Isles, especially between 1910 and 1930. In southern England it is now a characteristic type of rural area. Little owls have only been unable to establish themselves to the north of the Edinburgh-Glasgow line. The total British population is estimated to be 4,000 to 8,500 breeding pairs.

The little owl is classified as endangered (category 3) in the Red List of Germany's breeding birds. The total population for 2004 is estimated at 5,800 to 6,100 breeding pairs. North Rhine-Westphalia is home to approx. 76% of the German population. Large populations living in the head wooded lowlands of Westphalia , the head also wooded lower Niederrhein and in the western Jülicher Börde , where there are numerous grazed orchards. Hessen has the second largest breeding population in Germany and, unlike North Rhine-Westphalia, has seen a slight population increase over the last 25 years. In Bavaria, on the other hand, the little owl is a very rare breeding bird. After having withdrawn from former breeding areas for decades, the population , which had been reduced to Lower Franconia , was able to increase again through species protection measures.

In Switzerland , the little owl is now a rare species whose distribution is limited to the regions of Ajoie (17 breeding pairs), the canton of Geneva (30 to 40 breeding pairs) and the canton of Ticino (fewer than 10 breeding pairs).

Luxembourg is one of the countries with a dramatic population decline. In the 1960s, 3,400 to 4,200 breeding pairs lived here. In 2006, however, there were only 15 to 20 breeding pairs that breed in the far north and south of Luxembourg. Luxembourg is considered one of the countries where the species is likely to disappear completely. There is a similarly negative trend for Austria . Little owls were common in Austria until the 1970s. The breeding population is now estimated at only 70 to 100 pairs, most of which are found in the Weinviertel in Lower Austria . This region is characterized by traditional viticulture, and many little owls use old wine cellars as nesting places.

habitat

As a habitat, the little owl prefers open, richly structured terrain with a wide range of breeding caves, day hiding places and sitting areas and short, low-lying vegetation all year round. These habitat requirements are met by a large number of natural landscapes and landscapes that have been heavily designed by humans.

Primary habitats

The primary habitats of the little owl are the Eurosiberian steppe zones, subtropical semi-deserts, deserts such as the vast Mongolian Saxaul sand deserts and the temperate Asian arid regions. Its habitat mostly has vertical structures such as rocks and clay walls, where erosion and the activity of mammals and birds have created numerous caves, niches and crevices that can be used as nesting and resting places for the little owl. Otherwise, it uses cave-rich areas in steppe zones with burrows of mammals as meriones and mice , pikas , ground squirrels and field and Zieselmäusen . In the mountains of Central and East Asia, the little owl is a pronounced ground bird that prefers to nest and sleep in the burrows of the Himalayan marmots . Outside the range of this marmot species, it is absent on the high plateaus of these mountains. In Somalia, in addition to caves on the sand walls of dried up rivers, he also uses termite mounds as a seat guard and nesting site.

Secondary habitats

The secondary habitats of the little owl include the extensive karst landscapes and maquis of the Mediterranean area, which are characterized by semi-nomadic herd animal husbandry that has been practiced for centuries. Typical stone chewing habitats can also be found in vineyards, in the temple and ruin fields of the Mediterranean countries and in olive groves. In Spain the large, open cork oak groves are also populated by little owls.

In Western and Central Europe, the little owl mainly uses extensively managed permanent grassland areas such as cattle and mowing pastures, ruderal areas as well as paths and ditch edges, whose low vegetation and high food supply enable species-specific ground hunting. In Central Europe, pollarded willows , gardens with old trees and orchards are important little stone owl habitats. In parts of Western Europe, where the little owl's diet consists largely of earthworms, ideal little owl habitats consist of several year-round pastures. Their short sward favors the little owl's hunt for earthworms, which can be found mainly in the edge of the pastures. The pastures must therefore be as small as possible so that the little owl can find enough food. The little owl mainly uses masts and posts as sitting, calling and hunting stations. The relatively low paddock and fence posts play a major role in the hunt for the little owl, so that their density correlates positively with the population density of the little owl .

If one assumes in the sense of the mega herbivore hypothesis that open and semi-open habitats influenced by large herbivores are the original vegetation of Central Europe, then the little owl could also have "homeland rights" in Central Europe. Accordingly, human-influenced secondary habitats in Central Europe should only be understood as substitute habitats for the original open countries.

Elevation spread

In Central Europe, the little owl is a breeding bird in the forest-free lowlands and only rarely breeds at altitudes above 600 meters. In the southern regions of its range, however, the little owl also breeds in the mountains. It occurs in the Pyrenees at 1,200 meters above sea level and in places in the southern Spanish Sierra Nevada breeds at altitudes of 2,300 meters. In Inner Asia, little owls even settle at altitudes between 4,000 and 4,700 meters. Since the little owl is a distinct resident bird and does not leave its territory even with persistently high snow conditions and cold spells, high winter snow conditions are a barrier to spread.

Territory and settlement density

In general, little owl territories are small. Little owls on the Lower Rhine need only 1 to 2 hectares of permanent grassland all year round to cover their food needs. Although little owl territories do not overlap, considerable concentrations of little owls can occur in particularly favorable biotopes. In a year with an unusually strong occurrence of cockchafer, 25 pairs of little owls brooded on an area of 120 hectares east of Geneva . Individual breeding caves were only fifty meters apart. However, such settlement densities are exceptional. Even in the optimal biotopes of Central Europe, based on an area of 100 to 125 square kilometers, more than 1.5 breeding pairs per square kilometer occur only in rare exceptional cases. The zoologist Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim points out, however, that such large-scale settlement density calculations are only of limited significance because of the island-like occurrence of the little owl.

If there are sufficient food resources available, little owls stay in their territory all year round. The female lives in the territory of a male. Since loyalty to the breeding site is very pronounced, the partners of a couple often live in permanent marriage. A breeding site loyalty of up to five years has been proven for females.

Food and diet

Food spectrum

Little owls have a daily food requirement of 59 to 75 grams at an ambient temperature of 0 ° C and a requirement of 23 to 30 grams at 30 ° C. The food spectrum is very broad and ranges from beetles , earthworms and crickets to mice , small birds, amphibians and reptiles . The food composition varies depending on the season and geographical distribution, and the food spectrum of an individual little owl is greater, the greater the biodiversity of the respective habitat. Regardless of the season and area of distribution, small mammals are the main prey of the little owl, valued according to biomass and energy gain. Small rodents with a body weight of 10 to 30 grams are preferred. In Central Europe, the most important prey animal is the common field mouse , and a number of studies have shown a connection between the breeding success of the little owl and the size of the field vole population. Even in southern France, where this species only accounts for 6.5 percent of prey, it accounts for 50 percent of the biomass of the little owl's diet. In Asia, other representatives of the species-rich subfamily of voles also play a major role. Other important prey animals are gerbils and, especially in China, the gray dwarf hamsters . Small birds can play a bigger role, especially when there is snow and a breakdown in the mouse population. Species that hunt for food on the ground, such as starlings , thrushes , sparrows and larks, are preferred . In addition, the little owl occasionally steals young birds from their nests. Regionally, frogs and lizards can also play an important role in the food spectrum of the little owl.

Studies from Flanders and northern France show a high proportion of earthworms in the diet of the little owls that occur there. However, this is attributed to the greatly reduced supply that little owls find in these intensely agricultural regions. It is assumed that such populations, which have become food specialists, are particularly endangered.

Loot acquisition

The little owl is predominantly crepuscular and nocturnal. He usually hunts an hour or two after sunset and before sunrise. During the nestling period, it is also regularly active during the day due to the increased need for prey. The prey is primarily perceived visually. The little owl also reacts to acoustic stimuli such as the beeping of mice. The hunting method he uses depends on the type of vegetation. If the vegetation is low, it usually hunts directly from the ground or from a very low perch such as a stone or mound. If it discovers a beetle or a mouse, for example, it usually first approaches its prey with a short flight just above the ground and then follows it either in a fast run or with a few hops. Earthworms are almost always preyed on directly from the ground. If the vegetation is a little higher, so that the little owl cannot walk unhindered on the ground, high seat hunting plays a bigger role. Shaking and gliding flights are also documented. The prey is killed by a targeted bite on the head or the neck.

On summer nights, the little owl also hunts for insects around street lamps and well-lit houses and courtyards, which are attracted to the light. Its main prey here are predominantly moths. Little owls are also able to grab bats, and they steal eggs and young birds from bird nests such as those from starlings and house and tree sparrows . In Russia and Kazakhstan it has been observed that little owls regularly patrol the burrows of gerbils for potential prey. Individual burrows are used by the little owls as food depots when they catch more prey than they consume. Occasionally gerbil structures also serve as nesting places for the stone owls. Little owls, which find a large part of their prey in this way, show very clear signs of wear on the plumage of the head, shoulder and back.

With snow cover up to three centimeters thick, the success of little owls hunting rodents is higher compared to snow-free seasons, because this snow cover is too thin for rodents to dig passages below the snow surface and because they are more visible against the white underground. When fresh snow is seven to nine centimeters deep, however, the success of the little owl hunt drops significantly because rodents then predominantly stay under the surface of the snow. If there is a thick and high snowpack for more than three weeks, the mortality rate increases sharply.

Reproduction

A little owl year can be divided into the following phases:

- breeding season territorial courtship phase

- sexual courtship phase

- Breeding and rearing period

- Rest and moult phase

- Outside the breeding season, territorial courtship phase, also called autumn courtship

- winter rest phase

Mating already begins in the winter rest phase. In Central Europe, established pairs of little owls transmit together in the nesting holes as early as December.

Territorial defense and courtship

The little owl's willingness to defend its territory decreases after the young birds have been successfully rearing and the autumn courtship. It only intensifies again with the beginning of the courtship period. At the beginning of the breeding season, the male patrols the boundaries of the territory and often lets his loud guhg calls be heard during this time , which both shows other males the limits of their own territory and serves as a contact call to the females. In Central Europe, district owners react to sound mockups of these guhg calls, especially in the period from February to early April. Intruders are driven away by the territory owner by flying to them directly and chasing them to the border with loud cackling.

As soon as the female responds to the contact call, behaviors occur that primarily serve to strengthen the couple relationship. The calls and chants are much more restrained in the presence of a partner. In addition to simple territorial chants, males and females often call out lure, begging and excitement sounds. In addition, there is mutual nibbling and crawling as well as demonstrative joint territorial flights. They prefer to go to seat attendants, which are often used by the couple during the rest of the year. It is characteristic that the female there utters begging noises. The male gives prey to the female in response to these begging sounds. The number of prey animals handed over has an influence on the reproductive success of the couple: during this time, females store fat that they need for egg production and the subsequent hatching business. This behavior becomes increasingly intense and continues with visits to possible nesting sites and an increasing number of copulations. There are up to four copulations per night. When mating, the male rises on the back of the female. On average, it remains on the back of the female for up to 30 seconds. The actual act, on the other hand, only takes 3.1 seconds on average.

Nesting place and nesting place choice

Males show the female several places suitable for nesting within the territory. However, the actual choice of nesting site seems to be made by the female. Established couples use their breeding caves from the start of the mating phase. Little owls, which choose a new territory, only occupy their nesting holes after the end of the winter rest phase.

Little owls are very adaptable when it comes to their nesting sites. The nesting chamber only needs to be large enough to hold the eggs and later the young birds. It must offer the brood adequate protection from wind and rain and be as dark as possible. The entrance should be easily accessible for little owls, but it should offer adequate protection from predators. In Central and Western Europe, little owls prefer to use tree hollows as nesting sites. The proportion of tree broods is 92% in Great Britain, 85.3% in the Lower Rhine and 80% in France. Only a few tree species dominate. Fruit trees play a major role, and caves in willow , poplar , linden and oak are also used. Empty farmsteads, barns, chapels and occasionally inhabited houses and stables are also used by the little owl as a nesting place. Here it typically breeds in attics, in hollow spaces in false ceilings or in nesting boxes under eaves.

Little owls do not bring in any nesting material. Nest building activities are limited to cleaning the cave and scraping a hollow at the bottom of the cave. Jackdaws, starlings and tree sparrows are rivals for the little owl. Broods in polluted willows can even compete with mallards .

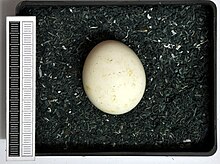

Breeding and breeding phase

The start of laying depends on the food supply and the weather. In Central and Western Europe, it usually falls in the last decade of April. The clutch usually consists of three to five eggs. The laying interval between the individual eggs is usually two days. The eggs are pure white and dull to moderately shiny. They weigh about 14 to 15 grams, are 3.3 to 4.0 inches long and 2.7 to 3.1 inches wide. Little owls usually raise only one brood per year; if the clutch is lost prematurely, replacement nestlings can be found. Females occasionally begin to breed after the first egg has been deposited. Some females only start breeding after the penultimate or last egg has been deposited. As a rule, the incubation period is between 22 and 30 days.

The female breeds alone; it is provided with prey by the male during the breeding season. Usually females only hunt for a few minutes during the brief breeding breaks. However, if the male is not able to provide the female with sufficient food, the female will extend the breeding breaks and hunt in the immediate vicinity of the breeding site. The young little owls hatch in Central Europe mostly in the 3rd May decade. The hatching distance depends on when the female started breeding. If it has only begun to breed with the laying of the last egg, the young birds hatch almost simultaneously. However, the hatching interval is often one to two days. During the first eight days of life, the young are fiddled intensely, whereas two-week-old nestlings are only fumbled during the midnight rest breaks. Cainism occurs among the siblings of a clutch, as in many other owl species, also in the little owl. Most of the time, the youngest nestlings are victims of cainism.

While the young birds are still in the nest hole, only the female feeds. The male carries prey, but usually hands it over to the female. The initially blind young birds respond to the feeding sounds of the female with a directed begging. From the 12th day of life they stand up to take prey by straightening their heel joints. The young birds leave the nest box between 22 and 24 days old and climb into the surrounding area. You are not yet fully fledged at this point; however, leaving the nest cavity early reduces the risk that predators will be able to grab them in the nest cavity. From the 30th to 32nd day of life, young birds can fly short distances. They stay in the vicinity of the brood cavity up to an age of 40 days and are fed by both parent birds. With increasing age, the young birds hunt themselves. The family association dissolves when the young birds have reached an age of two to three months. Most of the young birds settle at a distance of less than 10 kilometers from the place of birth. Just under 10 percent of young owls set up their territory at a distance of over 100 kilometers. In the autumn of their year of birth, the young little owls dominate almost the entire vocal repertoire and also spread the territory singing.

Breeding success and life expectancy

The reproduction rate of little owls is not high because of the very few secondary clutches, the relatively low hatching rate and the mortality of the nestlings. To compensate for the mortality rate of the species, each breeding pair would have to raise between 1.7 and 2.34 fledglings per year in order to keep the population stable. Indeed, the long-term reproductive rate in Europe fluctuates between these two values.

No nestlings hatch from around 13 percent of the eggs. 4.5 percent of the hatched nestlings die before they fledge. Even over 70 percent of little owls die in the first year of life. The average life expectancy for female little owls is four years. The one for males is slightly lower. The maximum age for wild owls is 15 years. Little owls kept in captivity reached an age of 18 years.

Autumn courtship

European little owls call increasingly from the end of July to indicate the boundaries of their territory. During this period young owls leave the parental territory. The second peak of the territorial courtship phase falls in October and November. During this time, the males patrol their territorial boundaries again and attack territorial intruders. This territorial phase of courtship is primarily aimed at pushing the young birds away and securing the prey potential for the coming winter.

Causes of mortality

The predators of the little owl include all larger species of owl, a number of birds of prey and carnivorous mammals such as the marten and stray domestic cats . Various studies show that the stone marten is one of the essential predators of the little owl. He is a food generalist who, as a skilled climber, reaches little owl caves and eats eggs and nestlings and occasionally also hunts adult little owls. Among the owls in particular eagle owls , tawny owls and long-eared owls are predators of the little owl. The tawny owl also plays a major role as a predator, as it competes with both nesting sites and food. Birds of prey that catch little owls include the goshawk , red kite , peregrine falcon and buzzard . Clutches are sometimes eaten by magpies and jackdaws .

The weather has a significant influence on the breeding success of little owls. Before the eggs are laid, days of rain lead to a below-average clutch size, as the females then hunt less and accordingly have a less good nutritional status. Persistent rain in May and June leads to increased nestling mortality. However, cold and snowy winters have a particularly strong influence on the little owl population in an area. The proportion of fat in the body weight of little owls is higher than that of barn owls, and they are therefore better able to survive periods of bad weather than this species of owl, which is also true to its location. However, little owls starve to death in long-term high snow cover. In Germany, after the harsh winters of 1978/79 and 1985/86, 30 and 38 percent, respectively, of the little owl nesting places were no longer occupied.

Little owls relatively often fall victim to road traffic, as they prefer to hunt on the ground and usually fly very low above the ground when switching between hunting grounds. Of every 100 dead little owls found, between 34 (Belgium, 2001) and 50 (Great Britain, 1991–1996) were run over. These numbers overestimate the proportion of little owls that die in this way, as they are easier to find than little owls that are struck by predators or starve to death. However, they are a clear indication that increasing traffic and greater road density have a negative impact on the little owl population. This statement is also supported by long-term evaluations such as those available for Great Britain. The proportion of road fatalities among little owls found dead was only six percent between 1910 and 1954 and was 35 percent for the period 1963 to 1970, before rising to the 50 percent cited above for 1991 to 1996.

Other anthropogenic factors contributing to the increase in the mortality of Steinkäuzen, the burdens are rodenticides and anthelmintics that are in prey of owls accumulated have. Even heavy metals such as cadmium and lead accumulate through the food chain in Steinkäuzen.

Systematics

The little owl belongs to the genus of little owls , to which four to six species are counted. One species is common in North America, the rest are found in the Old World .

According to classical taxonomy , up to 13 subspecies are distinguished for the little owl due to differences in body structure and plumage. Due to phylogenetic studies, this classification is currently in transition. The Central and Southern European forms based on the cytochrome b comparison differ significantly from forms in Asia Minor and Israel. According to the results available so far, it is possible that the subspecies noctua , vidalii , indigena , lilith and plumipes are species that belong to a superspecies . In their owl monograph, published in 2008, Claus König and Friedhelm Weick name only eight subspecies and treat A. lilith and A. spilogastra as separate species.

| subspecies | Distribution area | Distinguishing features of the individual subspecies |

|---|---|---|

|

Athene noctua noctua ( Scopoli , 1769) nominate form |

Sardinia, Corsica, Italy, Southeast Austria, Slovenia, Slovakia, Hungary, Moldova, Northern Romania, Denmark, Northern Germany, Poland, Baltic States. Distribution area overlaps with that of A. n. Vidalii in southern France, Switzerland, southern Germany, parts of Austria, the Czech Republic and Slovakia. With A. n. Indigena , the distribution area overlaps in Moldova, Croatia, Bosnia and in the Ukraine north of Kiev. Introduced in New Zealand. | The upper plumage is somewhat redder than that of the subspecies vidalii ; the white spots are a bit more washed out |

|

A. n. Vidalii Brehm , 1857 |

Western Europe; from the Netherlands and Belgium via France to the Iberian Peninsula. Introduced in the UK. | Darkest subspecies; White spots on the upper plumage are clearly delineated |

|

A. n. Indigena Brehm , 1855 |

Albania, Bosnia, southern and eastern Romania, southern Moldova and Georgia, in the southern direction of distribution to Crete and Rhodes, Turkey (except for the southeast), Levant, Transcaucasia and southwest Siberia, overlaps with bactriana in the southern Urals | Slightly paler than the nominate form |

|

A. n. Glaux ( Savigny , 1809) |

North Africa, coastal areas of Israel north to Haifa | Relatively dark subspecies; the stripes of the lower body plumage are dark brown |

|

A. n. Saharae ( Kleinschmidt , 1909) |

North and Central Sahara, closes in a southerly direction to the distribution area of glaux to | Paler than glaux , more pronounced white spots on the skull . Some authors believe that a distinction between saharae of glaux is not justified. |

|

A. (n.) Lilith Hartert, E , 1913 |

Cyprus, from Sinai to southeast Turkey, overlaps in Iraq with that of bactriana and that of saharae in Saudi Arabia | The palest subspecies, the underside of the body only slightly striped. See also Lilith-Kauz |

|

A. n. Bactriana Blyth , 1847 |

From the east coast of the Caspian Sea across the southeast of Azerbaijan and eastern Iran to the Altai Mountains, parts of Kazakhstan; overlaps west of the Ural River with indigena and further in Central Asia with orientalis | Larger than the previous subspecies, toes slightly more feathered. |

|

A. n. Ludlowi Baker, ECD , 1926 |

Kashmir, Tibetan Plateau to Xikang and the west of Qinghai, China | Similar to bactriana , but more clearly defined white spots |

|

A. n. Orientalis Severtzov , 1873 |

Pamir to Altai Mountains, Tianshan, Djungarian Alatau and Tacheng | Lighter than bactriana , more clearly defined dark stripes on the underside of the body |

|

A. n. Plumipes Swinhoe , 1870 |

Southeast of the Altai Mountains, Tannu-ola Mountains, Daurien | Brownish-gray subspecies |

|

A. n. Impasta Bangs & Peters , 1928 |

Qinghai and Ganus, China | Outwardly indistinguishable from the subspecies plumipes . However, genetic studies have confirmed the distinction between this subspecies. |

|

A. (n.) Spilogastra Heuglin , 1863 |

Red Sea from Port Sudan to the north of Eritrea | very small, pale brown top of the body. See also Ethiopian owl |

|

A. n. Somaliensis Reichenow , 1905 |

Eastern Ethiopia, Somalia | Smallest subspecies with a wing length of 134 to 143 millimeters. Is classified by some authors as a subspecies of a separate species Athene spilogastra . |

Human and little owl

The little owl in mythology and superstition

The oldest known representations of little owls can be found in Inner Mongolia and date from the period 8,000 to 7,500 BP . In the Bible , a bird with the Hebrew name כוס (kôs) is mentioned in three passages of the Old Testament , which is translated as screech owl . It is very likely that it is the little owl. Leviticus 11:17 and Deuteronomy 14:16 describe the owl as an unclean animal within the framework of the Jewish dietary laws , which believing Jews is forbidden to eat. In Psalm 102 , a lament, the worshiper expresses his loneliness and despair with the words "I am like an owl in the wasteland, like an owl in the ruins" (Psalm 102: 7).

In Greek mythology, the little owl was a symbol of the goddess Athena and this type of owl is represented accordingly frequently. The most famous ancient Greek coins include drachmas, which show the head of Athena on the obverse and a little owl with an olive branch on the reverse. These coins were from around 525 BC. In circulation. The reverse of such a coin is also depicted on the national side of today's Greek 1 euro coin . The little owl, along with eagle owls and barn owls, is one of the three species of owl mentioned by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis historia . Pliny assumes that the little owl is clever and reports (wrongly) that the little owl throws itself on its back in order to defend itself with its beak and claws against small birds when they hate it . In German popular superstition, the little owl in particular was regarded as the herald of death. Since it was often to be seen in church and cemetery, it was popularly known as church chicken , bird of the dead or corpse chicken . The fact that the little owl was once considered a messenger of death may be related to the circumstances under which its call was perceived. Because back then only the rooms of sick or dying people were lit. Their light attracted insects to the hospital room windows, which in turn attracted hunting little owls. For the relatives waking up at the bedside, the owl's call "kuwitt" had to sound like an ominous "Come with me!" And was perceived as an invitation to follow the little owl into the afterlife .

attitude

There is evidence for the 19th century that little owls were occasionally kept as ornamental birds. In Italy, tamed and docked little owls were allowed to hunt rodents and insects in the house and garden. The keeping of little owls was more common in order to use them in so-called hut hunting . This exploited the fact that many bird species react to owls with aggressive behavior if they discover them during the day (see: Hating ). Such hut hunts with little owls were in Italy from 350 BC. Practiced until the 20th century and in Germany from the 17th to the 20th century. In Italy larks were mainly caught in this way. The main trading center was Crespina , a small town near Pisa . Here, on September 29, little owls were traditionally sold, which had been taken from the nesting holes as nestlings and raised in human care. This trade has only been officially banned since the 1990s; However, due to the long cultural tradition of hunting with the little owl, special permits are still granted. There is also a rearing station for little owls near Crespina, which is maintained by hunters.

Preservation measures

In many European countries, the increasing disappearance of small-scale grazing has already had a negative impact on the little owl population. In the last decades the clearing of old fruit trees and pollarded willows and the conversion of green to arable land has led to further habitat destruction, which has resulted in the loss of nesting holes and day hiding places. One of the critical factors for the population density of little owls is the lack of suitable nesting sites. Protection programs therefore focus on the application of nesting aids in areas in which the occurrence of the little owl can still be expected. In Germany and other European countries, however, the conclusion was drawn that efforts to preserve the species would be in vain if politicians did not implement accompanying measures to ensure the continued existence of habitats such as orchards. In the southern Emsland and the Lower County of Bentheim, which used to be richly populated with little owls, the NABU was able to stabilize the population and slowly expand the area of distribution from the last existing islands by installing nesting facilities, which had become very rare due to the lack of old open barns or hollow trees .

supporting documents

literature

- James R. Duncan: Owls of the World . Firefly Books, Buffalo 2003, ISBN 1-55297-845-1 .

- Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim , Kurt M. Bauer: Handbook of the birds of Central Europe . Vol. 9 (Columbiformes to Piciformes). Aula Verlag 1980, 1994, ISBN 3-89104-562-X .

- Claus König , Friedhelm Weick : Owls of the World . Christopher Helm, London 2008, ISBN 978-0-7136-6548-2 .

- Jürgen Nicolai : Birds of prey and owls. Identify, get to know and protect birds of prey, owls and owls . Revised Aufl. Graefe and Unzer Verlag, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-7742-1858-7 (compass nature guide).

- Theodor Mebs , Wolfgang Scherzinger : The owls of Europe. Biology, characteristics, stocks . Kosmos, Stuttgart 2008 (updated and revised edition), ISBN 978-3-440-11642-5 .

- Dries van Nieuwenhuyse, Jean-Claude Génot, David H. Johnson: The Little Owl - Conservation, Ecology and Behavior of Athene noctua. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-88678-9 .

- Erhard Nerger / Dietmar Niemann / Helmut Lensing: The Little Owl (Athene noctua) in the Emsland and in the county of Bentheim, in: Study Society for Emsland Regional History (ed.), Emsländische Geschichte 24, Haselünne 2017, pp. 11-40.

- Siegfried Schönn, Wolfgang Scherzinger , Klaus-Michael Exo, Rottraud Ille: The Little Owl. Athene noctua . A. Ziemsen, Wittenberg Lutherstadt 1991, ISBN 3-7403-0240-2 ( Neue Brehm Bücherei . Volume 606).

sources

- ↑ Bird of the Year (Germany): 1972

- ↑ The little owl is the bird of the year 2021. In: birdlife.ch . Retrieved November 26, 2020 .

- ↑ Kauz. In: Digital dictionary of the German language . (In the Etymology section).

- ↑ Kauz. In: Jacob Grimm , Wilhelm Grimm (Hrsg.): German dictionary . tape 11 : K - (V). S. Hirzel, Leipzig 1873, Sp. 366-370 ( woerterbuchnetz.de ).

- ↑ a b Schönn et al., P. 30.

- ↑ a b Glutz et al., P. 503.

- ↑ a b c d Mebs et al., P. 312.

- ↑ a b Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 45.

- ↑ König et al., P. 435.

- ↑ Schönn et al., Pp. 32 and 33.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 37.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 253.

- ↑ a b c d e f Colin Harrison & Peter Castell: Young birds, eggs and nests of birds in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East , Aula-Verlag, Wiebelsheim 2004, ISBN 3-89104-685-5 , p. 185.

- ↑ a b Glutz et al., P. 504.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 167.

- ↑ Schönn et al., Pp. 173-175.

- ↑ a b c Schönn et al., P. 108.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 107 and p. 108.

- ↑ a b c Hans-Heiner Bergmann; Hans-Wolfgang Helb; Sabine Baumann; The voices of the birds of Europe - 474 bird portraits with 914 calls and chants on 2,200 sonograms , Aula-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-89104-710-1 ; P. 299.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 120.

- ↑ Mebs et al., P. 323.

- ↑ Mebs et al., P. 318.

- ↑ a b Schönn et al., P. 106.

- ↑ a b c d König et al., P. 437.

- ↑ Mebs et al., P. 317.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 106 and p. 107.

- ↑ a b c Glutz et al., P. 507.

- ↑ a b c d Glutz et al., P. 509.

- ↑ Hans-Heiner Bergmann; Hans-Wolfgang Helb; Sabine Baumann; The voices of the birds of Europe - 474 bird portrait with 914 calls and chants on 2,200 sonograms , Aula-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-89104-710-1 ; P. 298.

- ↑ Mebs et al., P. 320.

- ↑ Mebs et al., P. 321.

- ↑ a b Schönn et al., P. 18.

- ↑ a b c Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 27.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 29.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse, p. 85.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 92.

- ↑ quoted from Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 92.

- ↑ a b Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 107.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 27.

- ↑ a b Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 29.

- ↑ Christoph Grüneberg, Hans-Günther Bauer, Heiko Haupt, Ommo Hüppop, Torsten Ryslavy, Peter Südbeck: Red List of Breeding Birds in Germany, 5th version . In: Reports on bird protection . tape 52 , November 30, 2015, p. 19-67 .

- ↑ a b Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 113.

- ↑ M. Jöbges and S. Franke (Charadrius 42, Issue 4, 2006: 164–177)

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse, p. 113.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 22.

- ↑ Thomas Rödl, Bernd-Ulrich Rudolph, Ingrid Geiersberger, Kilian Weixler, Armin Görgen: Atlas of the breeding birds in Bavaria. Distribution 2005 to 2009 . Verlag Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart 2012, p. 118

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 131.

- ↑ a b Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 132.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse, p. 192.

- ↑ Glutz et al., P. 514.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 52 and p. 53.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 183.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 55.

- ^ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 167.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 53.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 56 and p. 57.

- ↑ a b c Mebs et al., P. 314.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 67.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 52.

- ↑ a b Schönn et al., P. 66.

- ↑ Einhard Bezzel: Birds. BLV Verlagsgesellschaft, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-405-14736-0 , p. 310.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 90.

- ↑ a b Schönn et al., P. 115.

- ↑ a b Glutz et al., P. 515.

- ↑ a b c Glutz et al., P. 516.

- ↑ a b c d e Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 234.

- ↑ Mebs et al., P. 324.

- ↑ a b c Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 230.

- ↑ a b Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 229.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 218.

- ↑ a b Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 231.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 81.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 82.

- ↑ a b Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 223.

- ↑ Schönn et al. P. 92.

- ↑ a b c Schönn et al., P. 71.

- ↑ a b Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 224.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 225.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 205.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 101.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 103.

- ↑ Heiner-Heiner Bergmann; Siegfried Klaus, Franz Müller, Wolfgang Scherzinger, Jon E. Swenson, Jochen Wiesner: The hazel grouse . Die Neue Brehm-Bücherei Volume 77, Westarp Wissenschaften, Magdeburg 1996, ISBN 3-89432-499-6 , p. 298 and p. 299.

- ↑ a b Mebs et al., P. 325.

- ↑ a b Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 236.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 237.

- ↑ a b c Schönn et al., P. 149.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 136.

- ↑ Glutz et al., P. 517.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 147.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 245 and Schönn et al., P. 149.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 243.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 251.

- ↑ a b Schönn et al., P. 163.

- ↑ Schönn et al., Pp. 154–155 and Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 251.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 156.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 158.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 159.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 265.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse, p. 257.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 161 and p. 163.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 188.

- ↑ Mebs et al., P. 331.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 264.

- ↑ a b Schönn et al., P. 192.

- ^ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 267.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse, p. 275.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse, p. 295.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 198.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 298.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 299.

- ↑ a b Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 282.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 281 and p. 282.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 283.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 24.

- ↑ König et al., P. 436.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al. P. 34.

- ↑ Schönn et al., P. 16.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuysen et al., P. 6.

- ↑ Bibelle Lexicon of the German Bible Society , accessed on November 14, 2009.

- ↑ Niewenhuyse et al., P. 10.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, BOOK I.1. In: perseus.tufts.edu. January 1, 2000, accessed March 27, 2019 .

- ^ Hanns Bächtold-Stäubli: Concise Dictionary of German Superstition , Volume 4, Weltbild, Augsburg 2005, ISBN 3-8289-0808-X

- ↑ Niewenhuyse et al., P. 15 and p. 17.

- ↑ a b Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 6.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 18.

- ↑ Rudolf Schaaf: The little owl on the ... / The little owl of Crespina . 2005 ( eulenwelt.de [PDF] News Letter 17).

- ↑ Einhard Bezzel: Birds. BLV Verlagsgesellschaft, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-405-14736-0 , p. 311.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuyse et al., P. 422.

Web links

- German Working Group for the Protection of Owls (AG Eulen)

- Practical contributions to the protection of little owls

- Page of the Society for the Conservation of Owls

- Athene noctua in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed January 31 of 2009.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Athene noctua in the Internet Bird Collection

- Age and gender characteristics (PDF; 5.5 MB) by J. Blasco-Zumeta and G.-M. Heinze (Eng.)

- Little owl feathers