Urartian Empire

Urartu |

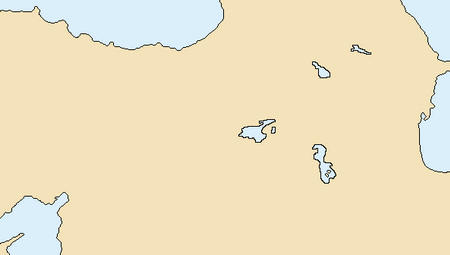

The Urartian kingdom also briefly Urartu ( Urartian Biainili , Assyrian KUR Artaya KUR URI , Akkadian KUR Uraštu , biblical probably Ararat ) was an ancient oriental empire around the Lake Van in Asia Minor , the later into the Urmia - and Sewanbecken and Arax level spread.

designation

Uruatri first appears in Central Assyrian texts from the 13th century BC. BC as a geographical name. Shalmaneser I describes a campaign against Uruatri, during which he destroyed eight countries (including KUR-Zingum) and 52 cities. It is commonly assumed that this Uruatri is identical to the neo-Assyrian Urartu, but Zimansky rejects such an equation due to a lack of evidence. Until the middle of the 9th century, the Assyrians localized Urartu to the west of Lake Van. Shalmaneser III names the cities of Arzaškun and Sugunia, their location is unknown.

The “Urartians” themselves never used the name Urartu, with the possible exception of the Topzawa stele . In the Kel-i-Shin language, Išpuini calls himself in the Akkadian version King of Nairi and Lord of the Tušpa City, in the Urartian King of the Biainili countries. Zimansky considers Biainili to be the native name of the kingdom of Urartu. Uraštu is mentioned in the cuneiform Behistun inscription by Darius I and here corresponds to Armenia in the Persian version. It is possible that the Assyrian name lived on as a geographical term under the Achaemenids .

As Friedrich Wilhelm König already emphasized, Urartu as (Assyrian name of a landscape) and the kingdom of Urartu (more correctly the Biainili countries) should not be equated. Johannes Friedrich calls the designation a "useful makeshift".

In the Old Testament one encounters Urartu as rrt , vocalized as Ararat .

location

Urartu was in eastern Anatolia , comprised parts of Transcaucasia and had its eastern border on Lake Urmia . The southern border formed the watershed between the small Zab and the Urmiasee, west of Mahabad and Miandoab ( inscription from Taštepe ). In the west it reached as far as the Erzincan area .

The area of Urartu is very mountainous, today there is an average of more than 80 days of snow a year, many passes are impassable from September to May. The mountain plateaus on which arable farming is possible are usually higher the further north you go. Only the valley of the Araxes is an exception. The southern Transcaucasia, first conquered under Argišti I, is also very mountainous, only the Ararat plain is below 1000 meters above sea level. The Ararat and Shirak plains form the most important arable farming areas in this region.

The passes to Mesopotamia are difficult and even today often impassable from November to early May. They are like "terrible mountains that rise like the point of a dagger against the sky".

expansion

The capital Tušpa (now Van ) was on Lake Van . Neighboring states and tribes included Assyria in the south, the Kingdom of the Manneans in the southeast and, in the late phase, the Cimmerians and Scythians in the north. At times, the Urartians reached Karkemiš on the western arc of the Euphrates in the south and Qulha in the northwest. The empire temporarily comprised Lake Sevan and the Araxes Valley in the north, Lake Urmia in the east and Rawanduz in the southeast. The maximum size was about 600 × 500 km². It is commonly believed that either Išpuini or his son Menua conquered Hasanlu in Mannai around 810 . Towards the end of the reign of Išpuini, campaigns to the southern and western parts of Lake Urmi took place, which are documented, among other things, by the inscriptions of Taštepe and Karagündüz .

Campaigns by Urartian rulers took place up to today's Georgian border, but this did not lead to a permanent conquest.

language

According to Hazenbos, the Urartian language is related to Hurrian and forms with it the Hurricane-Urartian group , which consists only of these two languages. Comparisons going beyond this (especially with Caucasian languages , especially Northeast Caucasian ) have not met with broad approval among experts.

Urartian loanwords in other languages are rare. The written tradition does not start until the end of the 9th century BC. u. Z. and consists of royal inscriptions carved in stone. Clay tablets (from Toprakkale , Kamir Blur , Bastam and Ayanıs, among others ) are only found after the reign of Rusa II. Their writing style differs significantly from the royal inscriptions carved in stone, which perhaps indicates a longer independent development.

Friedrich Wilhelm König suspected that the language, which in his opinion was very unfortunately called Urartian, was the language of the upper class. No people or tribe, only a dynasty is the bearer of this language . This question is closely related to the question of the spread of the Armenian language .

Research history and sources

The research history of Urartu goes back to 1827.

Important historical sources are the royal inscriptions that have been carved into the natural rock since Sarduri I. There are currently over 400 known. They describe either the conquests or the buildings of the respective rulers. Most of the time, they were attached after a campaign in a newly conquered area and formally describe the conquest and the toll levied. The longest of these inscriptions are the annals of Argišti I and Sarduri II. 35% of the inscriptions collected by GA Melikišvili (1960 and 1971) describe royal buildings (fortresses and irrigation systems). Sometimes the origin of the building material is also mentioned ("I brought these stones from the city of Alniunu. I built this wall"). Rock inscriptions were obviously reserved for the king.

A few clay tablets have been discovered in Bastam, Kamir Blur and Toprakkale, a total of 22 are known to date. Private archives have not yet been discovered. Mostly cuneiform was used, but there are also inscriptions with hieroglyphs that are vaguely similar to Luwian hieroglyphs . These also occur on metal objects and broken glass. Luwian inscriptions on vessels have come down to us from Altıntepe . Many items from the citadels have owner inscriptions, for example harness and helmets. Shields and spears served as votive gifts, which were recorded in inscriptions on the objects. These are another important epigraphic source. Since the kings usually use their father's name, they allow the genealogy to be reconstructed. About 290 are known to date. Most of the time, however, they come from objects in the art trade that have no proven origin.

There are no known settlements in the area of Lake Van in the Bronze Age . The burial grounds of Dilkaya and Karagündüz date from the early Iron Age . It is commonly believed that by the end of the third millennium, the population switched to nomadic ranching. Similar developments can be found in Transcaucasia and Iranian Azerbaijan .

history

Early Kings (Arzaškun in Nairi)

Rise to regional power

- from at least 832–825 BC BC Sarduri I son of Lutipri, in the beginning still regional ruler next to Kakia in the area of Nairi.

- 825-810 BC Chr. Išpuini

- 820-810 BC Chr. Išpuini and Menua

- 810-785 BC BC Menua , son of Išpuini

- 785-753 BC Chr. Argišti I.

- 753-735 BC BC Sarduri II , son of Argišti

- 735-714 BC BC Rusa I.

- 714-680 BC Chr. Argišti II. , Son of Rusa

- 680-639 BC Chr. Rusa II , son of Argišti, 690–660

End of the Assyrian sources

- Only Rusa Eriménaḫi (Rusa, son of Erimena) and Rusa Rusaḫi (Rusa, son of Rusa) occupied as rulers, the succession is controversial

- from 486 BC BC Province of the Achaemenid Empire

Economy

In Urartu, agriculture was possible without irrigation . The numerous irrigation systems either supplied special crops such as orchards and vineyards or improved grazing land for cattle, especially horses. The area of Lake Sevan is the wettest area of Urartu with approx. 500 mm of rainfall per year.

Agriculture was mainly practiced on the banks of the Great Lakes, Sevan , Urmia and Van . Several Urartian kings put on extensive irrigation systems. Menua built a canal, the Menua Canal ( Menuai pili , today Semiramis arkı) to ensure the water supply of Tušpa with the water from the Hosab Su . Other canal structures are documented by inscriptions from Adaköy , Bakımlı , Katembastı , Edremit and Hotanlı . Rusa II had, among other things, the Keşiş Gölü reservoir in Varak Dağı to secure the water supply for Tušpa. It still exists today. Further Urartian dams were built at Kırcagöl , Süphan Gölü and Milla Göleti (Arpayatağı), also the Gelincik Dam, Kırmızı Düzlük Dam (Deste Sor) and the Arç Dam (Dest Baradjı) date back to the Urartian era and some of them still function today. In his eighth campaign, Sargon describes how he had the irrigation canal that supplied Ulhu destroyed.

By analyzing macro residues (fruits, seeds) from Anzavurtepe , the cultivation of durum wheat (predominant), emmer, barley (probably two rows) and legumes (lentils, vetch and chickpea / grass pea) was proven. Lentils, chickpeas and vetch are known from Yoncatepe . Chickpeas have also been found in Kamir Blur and Bastam. The weeds included bedstraw, rye broth , knotweed, scaly heads and günsel . Naked grain clearly dominated. Viticulture must also have been important. Kamir Blur owned five magazines in which wine was kept in head-high pithoi. Piotrovski estimates its capacity at 34,000 liters. It is known from an inscription by Sarduri II that he planted a vineyard near Erciş . As Smith points out, landscape remodeling has been a dominant element in royal discourse. The construction of irrigation canals , gardens and vineyards as well as the construction of fortresses played an important role in the royal inscriptions, especially of the early rulers from Menua to Argišti I. “ The soil was uncultivated - no one had built anything here before ” is a standard formula that can be found in both Ayanıs and the Ararat plains.

"Landscapes are the instruments of political strategy, not an impact or a predetermined purpose ..." emphasizes Smith.

Nomadic cattle breeding was significant, as evidenced by the frequent occurrence of cattle in the tribute lists of the Urartian kings. Urartu was famous for its horses. Jars for buttering, on the other hand, are rather rare in the large fortresses, but are also more likely to be expected on alpine pastures . A number of vessels were found in Kamir Blur and Teišebai URU, which the excavator associated with the production of cheese. Such vessels were also found in Adilcevaz, Altıntepe, Aragatsa, Argištihinili, Bastam, Erebuni , Haykaberd, Kayalıdere, Ošakana and Tušpa.

Mining was certainly important; non-ferrous metals such as copper are available in the Urartu area. In the Lake Sevan area there is a concentration of fortresses on the Masrik Plain , which may have controlled the Sot'k 'gold mines. Iron ore , e.g. As the forging of weapons , was probably at Balaban and Pürneşe in Bitlis dismantled.

Settlements

Fortresses

Raffaele Biscione describes Urartu as a "non-urban state". The Urartian settlement system was characterized by fortresses, they were also administrative centers, religious centers and were used as storage facilities. They served as a refuge in times of war. Their garrisons were probably only small. Fortresses take on the role of non-existent cities in Urartu. However, the area outside the fortifications has rarely been explored, the examinations by Paul Zimansky in Ayanıs are an exception.

Biscione sees in the Urartian settlement pattern a mixture of the Caucasian settlement pattern with an aristocratic / military upper class and fortifications and a Mesopotamian system, which is based on an emphasis on agriculture, irrigation and a sophisticated civil administrative system. Bernbeck compares the function of Urartian castles with the imperial palaces of the German Staufer .

The construction of the Urartian fortresses probably goes back to the Transcaucasian Cyclopean fortresses of the early Iron Age, which, however, are less regular, especially in the distribution of the bastions and the wall thickness, and were built from unworked stones. They developed under the influence of the Assyrian and Hittite fortification technique .

The fortifications were mainly built by prisoners of war. The foundations of the fortresses were often carved into the bare rock as steps (previously misinterpreted as step temples). It was evidently preferred to build the fortresses on virgin land, the kings often boast of having tamed the wilderness. There are only a few exceptions, such as Horom, which is built on the remains of settlements from the Early Bronze Age. Perhaps the remains of previous structures were partially removed before the foundation stone was laid.

The walls made of standardized adobe bricks usually stood on a base made of dry masonry that was about 1 m high. Its outline was usually rectangular. Important buildings had regular ashlar walls. In the 8th century, the fortresses had alternating small and large bastions; in the 7th century, bastions of equal size were used. Basalt is the preferred building material . The fortress cities were called É.GAL (actually palace).

Kleiss distinguishes between an older and a younger phase. The older one is characterized by a rigid, right-angled grid, which makes complex terracing necessary. The outer walls have corner towers and rectangular bastions. Risalites are attached at regular intervals . Rectangular towers protrude both outward and inward. In the more recent phase, the shape and layout of the fortress, especially the outer wall, have been adapted to the terrain. The massive towers are being given up in favor of broad, slightly offset projections.

Biscione assumes four classes of fortresses, in addition to E.GAL Kleiss' small, medium and large fortresses, which presumably represent different levels of administration. Fortresses are mostly below 2000 m. In general, the Urartians seem to have concentrated on controlling fertile farmland and important traffic routes. The settlements of the early Iron Age often extend to much higher altitudes.

Images of Urartian fortresses come from the Balawat gates of Shalmaneser III, Assyrian palace reliefs. and Urartean bronze models, for example the incomplete copy from Toprakkale. It shows a double gate, stepped battlements, a narrow tower and narrow windows in the upper area of the wall. Stylized fortresses are also known on bronze belts, seals, ivory plates (probably pieces of furniture), stone reliefs and ornate bones. The motif of a sacred tree growing out of a stylized crenellated tower is known from bronze bowls made of Kamir Blur and was also used as a seal. Vajman and Movsisjan assume that it could be the Urartian symbol for fortress as a whole.

Important settlements in the Ararat plain included Erebuni , Argištihinili (two hills Armavir Blur and Davthi Blur near Armawir ), Karmir Blur , Oschakan , Aragaz and Iğdır . To the north of the Arax, an Urartian presence is so far only documented by inscriptions.

Suburbia

There were civil settlements around at least some of the forts. For example, large private houses were discovered on Güney-Tepe in Rusahinili, which Zimansky assigns to a Urartian elite. The highest concentration of red-polished Toprakkale goods was found here , and the animal bones also indicate better care. Large, apparently centrally planned structures have been found in the Pinarbaşi area. In Bastam there was also a suburbium 150 m below the citadel. It covered an area of 600 × 300 m, with large, EW-oriented houses. Finds of clay bulls indicate trading. Red-polished toprakkale pottery is common. The settlement was peacefully abandoned.

Streets

In the provinces of Muş, Bingöl and Elazığ, the almost 100 km long remains of an Urartian road have been preserved in the Bingöl Dağlari . It connected the Urartean heartland around Lake Van with Alzi , which was under Urartian rule for about 200 years, and the fertile Altınova near Elazığ . Since the Euphrates valley was too steep, the road was led through the Bingöl Dağı . The road is between 5.4 and 3.9 m wide and is bordered by stones. Bridges made of stone and wood led across streams. The road was probably unsuitable for cars as some sections were very steep. On the streets there were rectangular street stations at intervals of between 28 and 35 km. Their function probably corresponded to that of the later caravanserais , they offered safe night quarters and perhaps housed a small protection force. Such street stations are known from:

- Bastam, 8th century fortification, between Ak Cay and the plain of Kara Zia Eddin .

- Uzub Tepe between Bastam and Van

- Solhan and Zulümtepe on the road from Van to Elazığ. The station in Zulümtepe was rectangular and measured 87 × 44 m (Sevin 1986).

- The station in the plain of Bingöl, 28 m km west of Zülumtepe was on a hill and measured 39 × 29 m.

- Bahçecik 30 km west of Bingöl, 80 × 10 m with foundations cut into the rock (Kleiss 1981b). From here it is 25–30 km to Palu , the capital of Šebeteria .

- Norşuntepe in Alzi (today under the Keban reservoir ), 50 × 40 m. The station was excavated (Hauptmann 1969/70). From here could Harput be achieved.

Salvini identified a sacred road from Tušpa over the Kel-i-Shin pass to Musasir.

Rural settlements

According to Assyrian sources from 714 (8th campaign of Sargon II.) The rural settlements were mostly small, perhaps only individual farms, and were scattered. They have not yet been made accessible through excavations. Inspections in the Urmia area were able to record small settlements from 0.15 to hectares.

Political structure

The ruler of the country was the king. The royal headband ( kubšu ) and the scepter were symbols of rule . Members of the royal family held high political positions. The country was divided into provinces, which were ruled from a fortress, presumably by royal governors ( lu EN.NAM). How great the independence of the local rulers was is controversial. Wartke sees Urartu as an "official state". Bernbeck interprets Urartu as a segmentary state, until the time of Rusa II a “decentralized, loose association of smaller political units”.

Provinces:

- Urmia Plain: Provincial capital Qal'eh Ismail Agha

- South Lake Sevan: King's inscriptions from Tsovak, Tsovinar and Kra. Tsovinar ( d IM-I URU) was probably the provincial capital.

army

The army was led by the king personally, but Assyrian reports also name turtanus , i.e. generals.

Chariot

According to Urartian representations, the chariots were manned by two warriors, an archer next to the charioteer. Both were equipped with pointed helmets and wear a short-sleeved shirt and belt or chain mail . Later the charioteers often wear coats. The chariots have two six-spoke wheels and a very short body. According to Peter Calmeyer and Ursula Seidl , the equipment of the wagon and the harness of the horses corresponds to the Assyrian one, apart from a few details. A chariot is also depicted on a stele from Van. The tiller ornament of the Urartians consisted of a "disc with 5 upright tongues", this has been handed down both in the original (with the ownership inscription of Išpuini) and as a picture since Argišti I. Since Argišti I, the Urartian chariot wheels had eight spokes, just like the Assyrian since Tiglath-Pileser III.

The Yukari Anzaf shield also shows riders who, as in Assyria, appear in pairs.

military service

Under Sarduri II the šurele were exempted from military service. Diakonoff sees them as the real ethnic Urartians. After that, the army consisted mainly of the hurādele (LUA.SI), the warriors who perhaps came from the deported population of Urartus ( A.SI.RUM ).

Material culture

Urartian art is strongly Assyrian influenced, but Kendall wants to discover "a certain badly concealed barbaric undertone".

The Urartian material culture is very homogeneous and shows little change in the 200 years of the Urartian Empire. Paul Zimansky adopts strict state control of production. Van Loon divides Urartian art into a court style, which was directly controlled by the royal administration, and a folk style. G. Azarpay divides the development of material culture into four phases:

- Early stage

- Transition phase

- Second phase

- Late phase

In the later phase, narrative scenes and pictorial representations become rarer overall.

Ekrem Akurgal distinguishes:

- Ring style, 8th and 7th centuries

- Humpback style, 7th and 6th centuries

- Cubic style, ca.600 BC Chr.

Under Rusa II, the Assyrian influence on all areas of (state) material culture increased sharply.

The red, shiny polished Toprakkale pottery (Charles Burney) is considered to be typically Urartian. It occurs mainly in the great fortresses. The great pithoi , too, are almost entirely restricted to fortresses. Under Rusa II in particular, they were often marked with stamp seals, probably in centrally controlled workshops. Many of the ceramic shapes imitate metal vessels. Rhyta are usually richly decorated. Some of them have the shape of a shoe.

Even the great pithoi are almost exclusively restricted to fortresses. Sometimes the volume and sometimes the name of the fortress from which they come is noted on the shoulder of the vessel. The undecorated, brown to beige clay-ground commodity of utility ceramics was widespread far beyond Urartu, from Transcaucasia and Iran to northern Syria. Lamps were made from both red polished and heavy clay ware. Kernoi were pressed into molds. Painted pottery is rare. It usually has brown or black geometric paint on a yellowish background. Depictions of wild goats seem typical of the Ararat plain. Stone vessels seem to appear for the first time under Rusa II.

bronze

The tin content of the bronzes can be very different, occasionally lead bronzes are also documented, occasionally zinc was also added (Altıntepe and Toprakkale). Bronze was mainly used for vessels, furniture parts and protective weapons such as shields and helmets.

weapons

Swords, daggers, arrowheads and spearheads are mostly made of iron. Shields with plastic lion heads are known from Assyrian depictions of Musasir and the reports of Sargon. Such a bronze shield was excavated in Ayanıs. He was about 1 m in diameter and weighed 5.1 kg. Bronze-clad quivers are known from Toprakkale) and Karmir Blur. Some of them are figuratively or ornamentally decorated. In other cases only the mouth of the quiver was reinforced with a broad bronze band. Flat iron spout arrows are typical of the Urartians.

Furniture

Furniture in the fortresses was often elaborately designed. They had appliques and inserts made of bronze, which in turn could be decorated with semi-precious stones and stone inlays, for example for the representation of faces. Chairs or thrones were often cantilevered. The legs usually end in lion feet. They are interpreted as ceremonial thrones or gods thrones.

seal

Stamp seals have been used in the administration since the reign of Rusa II . Official seals usually have a cuneiform inscription, often the name of the king. Usually an "imperial style" is distinguished from the simpler, inscriptionless seals, which are also identified as private seals. In addition to royal seals, prince seals are also known. The role of these princes in the administration of the empire is unclear.

Clothing and costume

Textile remnants have not been preserved. The most important sources for Urartian clothing and armor are therefore Assyrian reliefs, Urartian minor art and grave finds. Unfortunately, most of the known Urartian graves have been looted and the additions ended up in the art trade.

As reliefs and statues show, the robes were sometimes decorated with embroidered borders and ornate embroidery.

Urartian men are usually depicted as bearded.

belt

Stamped bronze strips, which are usually described as belts, are known from the graves of Urartian nobles. However, they are usually not on the body of the buried person, but rather folded together with other bronze objects. Hamilton mentions a belt from Altıntepe near Erzincan , which was lying in a bronze cauldron with harness and parts of a chariot. Fine holes along the edges indicate that the bronze stripes may have been sewn onto a backing made of leather or some other organic material. The belts are very long, the incomplete example from Altıntepe was at least 90 cm long, for the also incomplete belt from Guschchi Hamilton reconstructed a length of up to 2 m. None of the known belts has a clasp.

The belts are often decorated figuratively, the example of Guschchi, for example, with lions, cattle, goats and an archer with a human torso and the body of a bird (or winged fish?). The belt of Nor-Areš shows a lion hunt in chariots, soldiers on foot and on horseback, as well as griffins and palmettes . Overall, hunting scenes with chariots are common. Bird men are also depicted on the belt of Anipemza . Perhaps they are related to the harpies depictions on the handle attachments of Urartian cauldrons. Other specimens have a geometric decoration made up of rows of hump hallmarks and ring hallmarks or rosettes. The copy from Altıntepe is inscribed in cuneiform and dates from the time of Argišti II.

Belts are also depicted on reliefs and statues. The "bronze statuette Va 774" from Toprakkale has a bronze belt.

interpretation

Piotrovsky interprets the belts as part of the armor of Urartian archers. The god symbols were supposed to give the wearers additional magical protection. Hamilton, however, wants to associate them with the harness of chariots.

Important sites

- Altıntepe , near Erzincan in eastern Turkey

- Anipemza , eight kilometers southeast of Ani on the border river Achurian on the Armenian side

- Guschchi, at the northern end of Lake Urmi

- Karmir Blur .

- Malaklju, near Iğdır on Mount Ararat

- Nor-Areš, near Arin-berd .

- Zakim, in the eastern Turkish province of Kars

religion

Gods

The inscription by Meher Kapısı first names Ḫaldi , then the weather god, the sun god and the “assembly of gods”. This is followed by Ḫutuini, presumably the god of victory. Since Išpuini, the Urartian god of war was waraldi, the god of war , who was depicted standing on a lion. Ḫaldi has been documented as part of the name since Central Assyrian times. Under Išpuini, Ḫaldi became an imperial god, although the center of his cult in Musasir was outside the actual Urartian empire. His companion was Aruba (i (ni) / Uarubani or Bagmaštu (or Bagbartu). His weapon is the GIŠ Šuri, according to King a chariot, according to Diakonoff (1952) a weapon and according to Salvini a sword or spear. On the cult shield of Yukarı Anzaf the leading god carries a flame-tonguing / shining spear, his legs are surrounded by similar flames / rays, while his upper body is surrounded by longer rays ( daši ). Later, Ḫaldi is apparently no longer represented figuratively, but his Šuri is depicted in the temple Bernbeck assumes that Sargon in Musaṣir also captured not an anthropomorphic statue of Ḫaldi, but a Šuri.

The bull was an attribute of the weather god Teišeba , as in the case of the Hurrian weather god Teššup . It is on the shield of Anzaf, recognizable by the bundles of lightning, but on a lion. His companion was Baba ("mountain"), his city Kumme / Qumenu . The bull was the animal of the sun god Šiwini , his companion was called Tušpuea , his city was Tušpa . He had an important sanctuary in the valley of the Bendimahi Çay near Muradiye , from which a stele also comes. These deities appear not only in lists of gods, but also in contracts. Otherwise only the moon god Šelardi can be identified with certainty from the lists . The fourth Urartian cult city, Erdia , can possibly be assigned to him. Irmušini had his temple in Çavuştepe near Erzen . Iubša was a Transcaucasian god to whom Argišti built a temple in Arin-berd; he does not yet appear on the Meher Kapısı inscription. As in Mesopotamia, the gods were represented with crowns of horns .

Mountains were also worshiped as divine and sacrificed, such as Mount Eidoru near Rusahinili ( Ayanıs ), probably the Süphan Dağı and d Qilibani, the Zımzımdağ east of Van. Adarutta was the god of Mount Andarutta on the border between Urartu and Musasir. He is also mentioned in the annals of Sargon.

temple

Tower temple

The characteristic tower temples (É, su-si / se ) were first built under Išpuini and are tied to fortresses. They are no longer built after the fall of Urartu. Such tower temples are known from Altıntepe , Anzavurtepe , Çavuştepe , Kayalıdere , Toprakkale (Van), and perhaps also Zernaki Tepe . They consist of a square building with massive stone foundations, very thick mud brick walls and an equally square cella inside. The corners usually protrude slightly. Access to the cella was through a short corridor and a recessed outer door. There was a small open courtyard in front of the tower. Often the tower was connected to other buildings. Since the tower temple in Ayanıs was surrounded by at least two-story buildings, Çilingiroğlu considers it possible that it could not be seen from outside.

| Location | Outer circumference | Cella |

|---|---|---|

| Altıntepe | 13.8 m | 5.2 m |

| Anzavurtepe | 13.6 m | 5 m |

| Bastam | 13.5 m | - |

| Çavuştepe | 10 m | 4.5 m |

| Kayalıdere | 12.5 m | 5 m |

| Toprakkale | 13.8 m | 5.3 m |

The temples are commonly believed to be about twice as high as they are wide. Stronach assumes that the Altıntepe Temple was at least 26 meters high. The temple of Ayanıs has been preserved to a height of 4.5. Whether the roof was flat or had gables is a matter of dispute. Bone and metal models of such temples show that they had three rows of recessed window slots, whether blind or open is unclear. Only in Anzavurtepe and Çavuştepe are the temples at the highest point of the fortress, otherwise the palace is located here. The walls of the cella and the courtyard were often painted or decorated with stone mosaics.

The Ḫaldi temple in Musasir , destroyed by Sargon II in 714 and only known from an Assyrian relief, was probably also a tower temple. However, it was quite low and had six pilasters on the facade, so far without parallels.

Votive offerings such as shields, helmets and bronze quivers hung on the facade and sometimes in the pillared courtyards inside the temple. Sometimes the cella was painted, like in Altıntepe. The temples were furnished with bronze kettles, candlesticks, bronze thrones and stools. Stronach assumes that the Urartian temples served as a template for the Achaemenid tower temples, but this is doubted by other researchers.

Gate temple

In addition, there were gate temples in which a niche represented a door from which the god Ḫaldi could perhaps step out of the rock. The inscription by Meher Kapısı begins with the words: Išpuini, son of Sarduri, and Menua, son of Išpuini built this door for Ḫaldi, the lord . Other gate temples can also be found in Yeşılalıç, Tabriz Kapısı and Hazine Kapısı from the time of Sarduri II.

Burials

Both body and cremation were practiced. In the latter case, the ashes were buried in an urn, usually without any additions. The bones were minced after the burn. Urns are often double or triple pierced in the upper part of the vessel body, which is interpreted as a soul hole . They are usually closed with a bowl. Most of the vessels are second-hand heavy pottery, which often shows signs of use. Usually they are egg-shaped jugs with a short neck, a flared lip and a flat bottom. They are usually around 30 cm high. Urns are also found in rock chamber tombs such as Adilcevaz , along with body burials. Rich burials have special grave ceramics, for example relief goods with lions and bulls' heads. In Altıntepe, metal vessels were used as urns. Graves were often dug into the rock, some of them had several chambers and probably served as family burials. Some rock tombs are associated with royal inscriptions. Urartean rock tombs are known for example from Van and Qal'ev Ismail Agha.

geography

mountains

| Urartean name | today's name | location | Remarks | source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eidoru at Rusaḫinili | Süphan Dağ | - | - | Çilingiroğlu / Salvini 1997 |

| Eritia | at Arzaškun | ? | - | |

| Qilibani | Zımzımdağ? | east of Van | - | Salvini 1994, 210 |

Rivers

| Urartean name | today's name | location | Remarks |

source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsanias | Murat su | Sevin 1988, 550 | ||

| Daianale | Murat sweet? | north of the Erciş dağı | Irrigation through Menua and Argišti I. | Diakonoff / Kashkai 1981 |

| Muna | Araxes | Armenia | Irrigation of Armavir through four channels, Argišti I. | Wartke 1993, 60 |

| Puranade | Euphrates | - | Sarduri II | Diakonoff / Kashkai 1981, 111 |

| Tura [...] | Diyala? | - | Argisti I | Diakonoff / Kashkai 1981, 111 |

| Alaini | - | at Van | Rusa diverts the river to secure the water supply for Rusaḫinili Qilbanikai | Garbrecht 1980 |

| Ildarunia | Hrazan? | Kublini Valley | Rusa I built the Umešini irrigation canal | Melikišvili 1960, no.281 |

| Usnu | Godar | near Qalatgar, Iran | - | Dyson 1989 |

See also

literature

Introduction to the subject

- Dietz-Otto Edzard : History of Mesopotamia. From the Sumerians to Alexander the Great. Munich 2004, pp. 192–195.

- V. Haas: The Empire of Urartu. An ancient oriental state in the 1st millennium BC Chr. Constance 1986.

- H.-D. Kaspar, E. Kaspar: Urartu. An ancient empire. A travel guide. Hausen 1986.

- HJNissen: History of the Ancient Near East . (Munich 1999) pp. 103-105.

- BB Piotrovsky: Urartu. The Kingdom of Van and its Art. London 1967.

- BB Piotrovsky: Urartu. (Geneva 1969).

- Mirjo Salvini: History and Culture of the Urartians. Darmstadt 1995.

- AT Smith: Prometheus Unbound: Southern Caucasia in Prehistory. New York 2005.

- H. Schmökel (ed.): Cultural history of the ancient Orient. Mesopotamia, Hittite Empire, Syria-Palestine, Urartu. (Augsburg 1995) pp. 606-657.

- KR Veenhof: History of the Ancient Orient up to the time of Alexander the Great. Göttingen 2001, p. 244 f.

- Ralf-Bernhard Wartke : Urartu. The empire on Mount Ararat. Mainz 1998.

- M. Zick: Turkey. Cradle of civilization. Stuttgart 2008, pp. 134-142.

- PE Zimansky: The Kingdom of Urartu in Eastern Anatolia. In: JM Sasson (Ed.): Civilizations of the Ancient Near East. Volume 2 (New York 1995) pp. 1135-1146.

history

- WC Benedict: Urartians and Hurrians. In: Journal of the American Oriental Society (JAOS) 80, 1960, pp. 100-104.

- A. Harrak: The Survival of the Urartian People. Bulletin of the Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies 25, 1993, pp. 43-49.

- A. Kalantar: Materials on Armenian and Urartian History. Neuchâtel 2003.

- R. Rollinger: The Median "Empire", the End of Urartu and Cyrus the Great's Campaign in 547 BC (Nabonidus Chronicle II 16). In: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Ancient Cultural Relations between Iran and West-Asia. Tehran 2004.

- Mirjo Salvini: La formation de l'état urartiéen. Hethitica 8, 1987, pp. 393-411.

- R. Vardanyan (Ed.): From Urartu to Armenia . Neuchâtel 2003.

swell

- Mirjo Salvini: Corpus dei Testi Urartei. Volumes 1–5, CNR / Istituto di studi sulle civiltà dell'Egeo e del Vicino Oriente, Rome 2008–2018.

geography

- M. Astour: The Arena of Tiglath-pileser III's Campaign Against Sarduri II (743 BC). Assur 2, 1979, pp. 69-91.

- H. Hauptmann, W. Kleiss: Topographical map of Urartu. Directory of localities and bibliography. Berlin 1976.

- PE Zimansky: Urartian Geography and Sargon's Eighth Campaign. In: Journal of Near Eastern Studies 49, 1990, pp. 1-21.

Architecture and urbanism

- R. Biscione: Pre-Urartian and Urartian Settlement Patterns in the Caucasus. Two Case Studies: The Urmia Plain, Iran and the Sevan * Basin, Armenia. In: AT Smith, KS Rubinson (Eds.), Archeology in the Borderlands. Investigation in Caucasia and Beyond (Los Angeles 2003), pp. 167-184.

- CA Burney, GRJ Lawson: Measured Plans of Urartian Fortresses. In: Anatolian Studies (AnSt) 10. 1960. pp. 177-196.

- TB Forbes: Urartian Architecture (Oxford 1983).

- G. Garbrecht: The Water Supply System at Tuspa (Urartu). In: World Archeology (WorldA) 11, 1979-1980, pp. 306-312.

- F. Işik: The open rock sanctuaries of Urartus and their relationship to those of the Hittites and Phrygians (Rome 1995).

- K. Jakubiak: The Development of Defense System of Eastern Anatolia (The Armenian Upland). From the Beginning of the Kingdom of Urartu to the End of Antiquity. (Warsaw 2003).

- Wolfram Kleiss: Size comparisons of Urartian castles and settlements. In: RM Boehmer, H. Hauptmann (Hrsg.): Contributions to ancient history of Asia Minor. Festschrift for Kurt Bittel (Mainz 1983) pp. 282–290.

- Wolfram Kleiss: On the reconstruction of the Urartean temple. Istanbuler Mitteilungen (IstMitt) 13/14, 1963/63, pp. 1–14.

- B. Öğün: The Urartian palaces and the burial customs of the Urartians. In: D. Papenfuss, VM Strocka (ed.): Palast und Hütte. Contributions to building and living in antiquity by archaeologists, prehistory and early historians. Conference contributions to a symposium of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation Bonn-Bad Godesberg, 25. – 30. November 1979, Berlin (Mainz 1982) pp. 217-222.

- E. Rehm: High towers and shields. Temples and temple treasures in Urartu. In: Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft (MDOG) 136, 2004, pp. 173–194.

- D. Stronach: Urartian and Achaemenian Tower Temples. Journal of Near Eastern Studies (JNES) 26, 1967, pp. 278-288.

- T. Tanyeri-Erdemir: Agency, Innovation, Change, Continuity. Considering the Agency of Rusa II in the Production of the Imperial Art and Architecture of Urartu in the 7th Century BC. In: DL Peterson, LM Popova, AT Smith (Eds.): Beyond the Steppe and the Sown. Proceedings of the 2002 University of Chicago conference on Eurasian Archeology. (Leiden 2006) pp. 264-281.

- D. Ussishkin: On the Architectural Origin of the Urartian Standard Temples. In: A. Çilingiroğlu, DH French (Ed.): The Proceedings of the Second Anatolien Iron Ages Colloquium. 4-8 May 1987, Izmir (Oxford 1991) pp. 117-130.

Arts and Culture

- H. Avetisian: Urartian Ceramics from the Ararat Valley as a Cultural Phenomenon (A Tentative Representation). Iran & the Caucasus 3, 1999/2000, pp. 293-314.

- G. Azarpay: Urartian Art and Artifacts. A Chronological Study. (Berkeley 1968).

- H. Born: Protective weapons from Assyria and Urartu. (Mainz 1995).

- Z. Derin: The Urartian Creamtion Jars in Van and Elazig Museums. In: A. Çilingiroğlu, DH French (Ed.): The Proceedings of the Third Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium held at Van. 6-27 August 1990 (Oxford 1994) pp. 46-62.

- S. Kroll: Ceramics of Urartian fortresses in Iran. A contribution to the expansion of Urartu in Iranian Azarbaijan. (Berlin 1976).

- R. Merhav (Ed.): Urartu. A Metalworking Center in the First Millennium BCE exhibition at the Israel Museum, May 28 to October 7, 1991 (Jerusalem 1991).

- U. Seidl: Bronze Art Urartus. (Mainz 2004).

- U. Seidl: Achaemenid borrowings from the Urartian culture. In: H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg, A. Kuhrt, M. Cool Root (eds.): Continuity and Change. Proceedings of the Last Achaemenid History Workshop. April 6-8, 1990, Ann Arbor, Michigan (Leiden 1994) pp. 107-129.

- PE Zimansky: Urartian Material Culture as State Assemblage. Bulletin of the American Association of Oriental Research 299, 1995, pp. 103-115.

Writing and language

- RD Barnett: The Hieroglyphic Writing of Urartu. In: K. Bittel, PHJ Houwink, E. Reiner (Eds.): Anatolien Studies Presented to Hans Gustav Güterbock on the Occasion of his 65th Birthday. (Istanbul 1974) pp. 43-55.

- GA Melikişvili: The Urartean language. (Rome 1971).

- Mirjo Salvini, I. Wegner: Introduction to the Urartian Language (Wiesbaden 2014), ISBN 978-3-447-10140-0

- PE Zimansky: Archaeological Inquiries into Ethno-linguistic Diversity in Urartu. In: R. Drews (Ed.): Greater Anatolia and the Indo-Hittite Language Family. Papers Presented at a Colloquium Hosted by the University of Richmond, 18. – 19. March 2000. (Washington 2001) pp. 15-26.

politic and economy

- R. Bernbeck: Political structure and ideology in Urartu. Archaeological Communications from Iran and Turan (AMIT) 35/36, 2003–2004, pp. 267–312.

- F. Özdem: Urartu. War and Aesthetics (Istanbul 2003).

- Mirjo Salvini: The Impact of the Urartu Empire on the Political Conditions on the Iranian Plateau. In: R. Eichmann, H. Parzinger (Hrsg.): Migration und Kulturtransfer. The change of Near Eastern and Central Asian cultures in the upheaval from the 2nd to the 1st millennium BC. (Bonn 2001) pp. 343-256.

- Zimansky, PE: Ecology and Empire. The Structure of the Urartian State (Chicago 1985).

Conference volumes, Festschriften and miscellaneous

- O. Belli: Van. The Capital of Urartu. Eastern Anatolia. Ruins and Museum. (Istanbul 1989).

- R. Biscione: The North-Eastern Frontier. Urartians and Non-Urartians in the Sevan Lake Basin. (Rome 2002).

- CA Burney: A First Season of Excavations at the Urartian Citadel of Kayalidere. Anatolian Studies (AnSt) 16, 1966, pp. 55-111.

- G. Garbrecht: The dams of the Urartians. In: G. Garbrecht (Ed.): Historical dams. (Stuttgart 1987) pp. 139-145.

- W. Kleiss: Bastam II. Excavations in the Urartean complex 1977–1978. Teheraner Research (TeherF) 5 (Berlin 1979).

- K. Köroğlu (Ed.): Urartu. Transformation in the East. (Istanbul 2011).

- H. Saglamtimur (Ed.): Studies in Honor of Altan Çilingiroğlu. A Life Dedicated to Urartu on the Shores of the Upper Sea. (Istanbul 2009).

- J. Santrot (Ed.): Arménie. Trésors de l'Arménie ancienne des origines au IVe siècle. (Paris 1996).

- AT Smith (Ed.): Bianili-Urartu. Proceedings for the conference in Munich, 12. – 14. October 2007 (Munich 2007).

Web links

- Electronic Corpus of Urartian Texts (eCUT) Project. Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (electronic corpus of Urartean texts with English translations and general information on Urartu and the Urartians as well as extensive bibliography, created by Birgit Christiansen on the basis of Mirjo Salvini's five-volume Corpus dei Testi Urartei, Rome 2008-2018)

- Ernst Kausen : Hurrian and Urartian , 2005

- Van Museum and Historical Ruins

- Altıntepe, excavation in Erzincan

- Useful bibliography

Individual evidence

- ^ Paul E. Zimansky: Archaeological inquiries into ethno-linguistic diversity in Urartu. In: Robert Drews (Ed.): Greater Anatolia and the Indo-Hittite Language family. Institute for the Study of Man, Washington 2001, ISBN 0-941694-77-1 , p. 18.

- ↑ 2nd supplement to the communications of the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Ethnology. 1983, p. 27.

- ^ Paul Zimansky: Urartian material culture as state assemblage. In: Bulletin American Association of Oriental Research. 299, 1995, note 6.

- ^ Paul Zimansky: Urartian material culture as state assemblage. In: Bulletin of the American Association of Oriental Research. 299, 1995, p. 105.

- ^ Friedrich Wilhelm König: Handbook of the Chaldic inscriptions. Archive for Orient Research. Supplement 8. Graz 1955, 1957

- ↑ Johannes Friedrich: Old Asia Minor Languages, Handbook of Oriental Studies. 1st Dept., The Near and Middle East. Volume 2: Cuneiform script research and ancient history of the Near East. Section 1–2: History of Research, Language and Literature. Lfg. 2. Brill, Leiden 1969, p. 34.

- ↑ Wolfram Kleiss: Bastam, an Urartian citadel complex of the 7th century BC In: American Journal of Archeology . 84/3, 1980, p. 304.

- ↑ Tuğba Tanyeri-Erdemir: Agency, innovation, change, continuity: considering the agency of Rusa II in the production of the imperial art and architecture of Urartu in the 7th Century BC. P. 268.

- ^ Paul E. Zimansky: Archaeological inquiries into ethno-linguistic diversity in Urartu. In: Robert Drews (Ed.): Greater Anatolia and the Indo-Hittite Language family. Institute for the Study of Man, Washington 2001, p. 17.

- ^ Kemalettin Köroğlu: The Northern Border of the Urartian Kingdom. In: Altan Çilingiroğlu / G. Darbyshire. H. French (Ed.): Anatolian Iron Ages 5, Proceedings of the 5th Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium Van, 6-10. August 2001. British Institute of Archeology at Ankara Monograph. 3, Ankara 2005, p. 99.

- ^ Adam T. Smith: The Making of an Urartian Landscape in Southern Transcaucasia: A Study of Political Architectonics. In: American Journal of Archeology. 103/1, 1999, p. 49

- ^ HF Russell: Shalmaneser's Campaign to Urartu in 856 BC and the historical geography of Eastern Anatolia According to the Assyrian sources. In: Anatolian Studies . 34, 1984, 174.

- ↑ Shalmanasser III, Kurkh Monolith, ii 41–45

- ^ W. Kleiss, On the expansion of Urartus to the north. Archaeological Communications Iran 25 1992, pp. 91–94

- ↑ 2nd supplement to the communications of the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Ethnology 1983, 26

- ^ Dyson and Muscarella 1989

- ↑ Miroslav Salvini: The Influence of the Urartu Empire on the Political Conditions on the Iranian Plateau . In: Ricardo Eichmann , Hermann Parzinger (Hrsg.): Migration und Kulturtransfer. Bonn 2001, p. 349

- ^ Kemalettin Köroğlu: The Northern Border of the Urartian Kingdom. In: Altan Çilingiroğlu / G. Darbyshire. H. French (Ed.): Anatolian Iron Ages 5, Proceedings of the 5th Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium Van, 6.-10. August 2001. British Institute of Archeology at Ankara Monograph 3 (Ankara 2005) p. 103.

- ↑ Joost Hazenbos , Hurrian and Urartian. In: Michael P. Streck (Ed.): Languages of the Old Orient. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2005. ISBN 3-534-17996-X .

- ^ Paul Zimansky, Urartian material culture as state assemblage, Bulletin American Association of Oriental Research 299, 1995, 105

- ↑ Tuğba Tanyeri-Erdemir: Agency, innovation, change, continuity: considering the agency of Rusa II in the production of the imperial art and architecture of Urartu in the 7th Century BC. P. 267

- ^ Robert Drews (Ed.): Greater Anatolia and the Indo-Hittite Language family. Washington: Institute for the Study of Man, 2001, 78.

- ^ Friedrich Wilhelm König: Handbook of the Chaldic inscriptions. Archive for Orient Research. Supplement 8. Graz 1955, 1957

- ↑ Boris Pjotrowski: Urartu. Archaeologica Mundi, Volume 26, Munich 1980, p. 12 ff.

- ↑ Tuğba Tanyeri-Erdemir: Agency, innovation, change, continuity: considering the agency of Rusa II in the production of the imperial art and architecture of Urartu in the 7th Century BC. P. 276

- ^ Adam T. Smith: Rendering the political aesthetic: Political legitimacy in Urartian representations of the built environment. In: Journal Anthropological Archeology 19, 2000, pp. 131-163.

- ↑ Melikišvili 1960, No. 1

- ↑ Miroj Salvini: The Urartean clay tablet VAT 7770 from Toprakkale. Ancient Oriental Research 34/1 2007, pp. 37–50.

- ↑ Wolfram Kleiss: Bastam, an Urartian citadel complex of the 7th century BC American Journal of Archeology 84/3, 1980, p. 301.

- ^ FW König: Handbook of Chaldic Inscriptions. Graz 1955

- ^ Adam T. Smith: Rendering the Political Aesthetic: Political legitimacy in Urartian representations of the built environment. In: Journal Anthropological Archeology 19, 2000, p. 132.

- ^ Veli Sevin: The Origins of the Urartians in the Light of the Van / Karagündüz Excavations. Anatolian Iron Ages 4. Proceedings of the Fourth Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium, Mersin, May 19-23, 1997. Anatolian Studies 49, 1999, pp. 159-164.

- ^ Veli Sevin: The Origins of the Urartians in the Light of the Van / Karagündüz Excavations. Anatolian Iron Ages 4th Proceedings of the Fourth Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium, Mersin, 19. – 23. May 1997. Anatolian Studies 49, 1999, p. 159.

- ↑ after Salvini 2006

- ↑ Oktay Belli: Urartian dams and artificial lakes in Eastern Anatolia. In: A. Çilingiroğlu, H. French (Ed.): Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium. Anatolian Iron Ages 3: Anadolu Demir Çaglari 3, Van, 6. – 12. August 1990: III. Anadolu Demir Çaglari Sempozyumu Bildirileri. London: British Institute of Archeology at Ankara 1994, pp. 9-30.

- ↑ Emel Oybak Dönmez: Urartian crop plant remains from Patnos (AGRI), Eastern Turkey. Anatolian Studies 53, 2003, 90

- ↑ Emel Oybak Dönmez / Oktay Belli, Urartian Plant Cultivation at Yoncatepe (Van), Eastern Turkey. Economic Botany 61/3, p. 296

- ^ Paul Zimansky, An Urartian Ozymandias, 152

- ^ Charles Burney: Urartian Irrigation Works. In: Anatolian Studies. 22, 1972, p. 182

- ^ A b Adam T. Smith: The Making of an Urartian Landscape in Southern Transcaucasia: A Study of political Architectonics. American Journal of Archeology 103/1, 1999, p. 46.

- ↑ Melikisvili 137

- ↑ 2nd supplement to the communications of the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Ethnology. 1983, p. 28.

- ↑ Haik Avetisian: Urartian Ceramics from the Ararat Valley as a cultural phenomenon (a tentative representation). In: Iran & the Caucasus. 3, 1999/2000, p. 295.

- ^ O. Belli, Ore deposits and mining in eastern Anatolia in the Urartian period. In: Rivka Merhav (ed.), Urartu: a metalworking center in the first millennium BCE. Jerusalem, Israel Museum 33 ff.

- ↑ Raffaele Biscione, Simon Hmayakyan Neda Parmegiani (Ed.): The North-Eastern frontier Urartians and non-Urartians in the Sevan Lake basin. CNR, Istituto di studi sulle civiltà dell'Egeo e del Vicino Oriente, Rome 2002, p. 365.

- ^ Paul Zimansky: Urartian material culture as state assemblage. In: Bulletin American Association Oriental Research 299, 1995, p. 105.

- ^ E. Stone, P. Zimansky: The Urartian Transformation in the outer Town of Ayanıs. In: Adam T. Smith, Karen S. Rubinson (Eds.): Archeology in the Borderlands. Pp. 213-228.

- ^ Reinhard Bernbeck : Political structure and ideology in Urartu. In: Archaeological communications from Iran and Turan. 35/36, p. 273.

- ^ Adam T. Smith, Koriun Kafadarian: New plans of Early Iron Age and Urartian fortresses in Armenia: A preliminary report on the Ancient Landscapes Project. Iran 34, 1996, 37.

- ^ Wolfram Kleiss: Notes on the chronology of Urartian defensice architecture. In: Altan Çilingiroğlu / DH French (ed.): Anatolian Iron Ages 3. British Institute of Archeology at Ankara Monograph 3 (Ankara 1994), p. 131.

- ^ Adam T. Smith: Rendering the Political Aesthetic: Political legitimacy in Urartian representations of the built environment. In: Journal Anthropological Archeology. 19, 2000, p. 144.

- ^ Adam T. Smith: Rendering the Political Aesthetic: Political legitimacy in Urartian representations of the built environment. In: Journal Anthropological Archeology. 19, 2000, note 20.

- ↑ Miroj Salvini: History and Culture of the Urartians. Darmstadt 1995, p. 133.

- ↑ Miroj Salvini: History and Culture of the Urartians. Darmstadt 1995, p. 132.

- ^ A. Gunter: Representations of Urartian and Western Iranian fortress architecture in Assyrian reliefs. Iran 20, 1982, pp. 103-112.

- ↑ britishmuseum.org ( Memento of the original dated August 7, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Adam T. Smith: Rendering the Political Aesthetic: Political legitimacy in Urartian representations of the built environment. In: Journal Anthropological Archeology 19, 2000, p. 144

- ↑ AA Vajman: Urartskaya ieroglifika. In: VG Lukonin (ed.): Kultura Vostoka. (Aurora, Leningrad 1978), pp. 100-105

- ↑ A. Ju. Movsisjan: The hieroglyphic script of the Kingdom of Van. (Gitutjun, Erevan 1998), Armenian, quoted from Smith (2000)

- ↑ Haik Avetisian: Urartian Ceramics from the Ararat Valley as a cultural phenomenon (A tentative representation). In: Iran & the Caucasus 3, 1999/2000, pp. 293-314

- ↑ Kemalettin Köroğlu, The Northern Border of the Urartian Kingdom. In: Altan Çilingiroğlu / G. Darbyshire. H. French (Ed.): Anatolian Iron Ages 5th Proceedings of the 5th Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium Van, 6-10. August 2001. British Institute of Archeology at Ankara Monograph 3, Ankara 2005, p. 100.

- ^ Paul E. Zimansky: Archaeological inquiries into ethno-linguistic diversity in Urartu. In: Robert Drews (Ed.): Greater Anatolia and the Indo-Hittite language family. (Washington: Institute for the Study of Man, 2001), 23

- ↑ Wolfram Kleiss: Bastam, an Urartian citadel complex of the 7th century BC American Journal of Archeology 84/3, 1980, 300.

- ↑ Veli Sevin: The oldest highway: between the regions of Van and Elazig in eastern Anatolia. Antiquity 62, 1988, p. 547

- ↑ Veli Sevin: The oldest highway: between the regions of Van and Elazig in eastern Anatolia. In: Antiquity. 62, 1988, pp. 547-551.

- ^ Wolfram Kleiss: Bastam, an Urartian citadel complex of the 7th century B.C. In: American Journal of Archeology. 84/3, 1980, p. 99.

- ↑ Veli Sevin, The oldest highway: between the regions of Van and Elazig in eastern Anatolia. Antiquity 62, 1988, 550

- ↑ Salvini 1984, p. 79 ff.

- ^ Reinhard Bernbeck: Political structure and ideology in Urartu. In: Archaeological Communications from Iran and Turan 35/36, p. 277

- ↑ Zimanskzy 1995

- ↑ RB Wartke, Urartu, the realm on the Ararat. Mainz 1993, 65

- ^ Reinard Bernbeck: Political structure and ideology in Urartu. In: Archaeological Communications from Iran and Turan 35/36, p. 270

- ↑ Peter Calmeyer, Ursula Seidl: An early Urartian representation of victory . In: Anatolian Studies 33, 1983, plate 1

- ↑ Peter Calmeyer, Ursula Seidl: An early Urartian representation of victory . In: Anatolian Studies 33, 1983, p. 107

- ↑ Peter Calmeyer, Ursula Seidl: An early Urartian representation of victory . In: Anatolian Studies 33, 1983, p. 106

- ↑ Peter Calmeyer, Ursula Seidl: An early Urartian representation of victory . In: Anatolian Studies 33, 1983, p. 106

- ↑ Archaeological Communications Iran 13, 1980, p. 75

- ^ John AC Greppin and IM Diakonoff: Some effects of the Hurro-Urartian people and their languages upon the earliest Armenians. Journal of the American Oriental Society 111/4, 1991, p. 727.

- ↑ "... tinctured with a certain ill-concealed undercurrent of barbarism" after Timothy Kendall: Urartian Art in Boston: Two Bronze Belts and a Mirror . Boston Museum Bulletin 75, 1977, Jan.

- ↑ Maurits van Loon: Urartian Art. Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologische Instituut. Istanbul 1966, p. 168, Tuğba Tanyeri-Erdemir: Agency, Innovation, change, continuity: considering the agency of Rusa II in the production of the imperial art and architecture of Urartu in the 7th Century BC. P. 268.

- ^ Paul Zimansky: Urartian material culture as state assemblage. Bulletin of the American Association of Oriental Research 299, 1995, p. 111.

- ↑ Maurits van Loon: Urartian art. Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologische Instituut, Istanbul 1966, p. 166.

- ↑ G. Azarpay: Urartian Art and Artefacts , Berkeley in 1968

- ↑ a b Tuğba Tanyeri-Erdemir: Agency, Innovation, change, continuity: considering the agency of Rusa II in the production of the imperial art and architecture of Urartu in the 7th Century BC. P. 272.

- ↑ Zafer Derin: Potters' Marks of Ayanıs Citadel. Van. Anatolian Studies 49, 1999, p. 94.

- ↑ Haik Avetisian: Urartian Ceramics from the Ararat Valley as a cultural phenomenon (a tentative representation). Iran & the Caucasus 3, 1999/2000, p. 302.

- ↑ a b Haik Avetisian: Urartian Ceramics from the Ararat Valley as a cultural phenomenon (a tentative representation). Iran & the Caucasus 3, 1999/2000, p. 303.

- ↑ a b Wolfram Kleiss: Bastam, an Urartian citadel complex of the 7th century BC American Journal of Archeology 84/3, 1980, p. 303.

- ↑ Haik Avetisian: Urartian Ceramics from the Ararat Valley as a cultural phenomenon (a tentative representation). Iran & the Caucasus 3, 1999/2000, p. 301.

- ^ A b M. J. Hughes, JE Curtis, ET Hall: Analyzes of Some Urartian Bronzes. In: Anatolian Studies 31, 1981, p. 143

- ↑ Altan Çilingiroğlu: Recent excavations at the Urartian fortress of Ayanıs. In: Adam T. Smith / Karen S. Runinson (eds.): Archeology in the borderlands. Investigations in Caucasia and beyond. Monograph 47, Cotsen Institute of Archeology, UCLA, pp. 209–212)

- ↑ BM 135456, archived copy ( memento of the original from March 10, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ RD Barnett: More Addenda from Toprak Kale. Anatolian Studies 22, 1972 (Special Number in Honor of the Seventieth Birthday of Professor Seton Lloyd, p. 170

- ^ RD Barnett, More Addenda from Toprak Kale. Anatolian Studies 22, 1972 (Special Number in Honor of the Seventieth Birthday of Professor Seton Lloyd, 172

- ^ Gerhard Rudolf Meyer : On the bronze statuette VA 774 from Toprak-Kale. In: Research and Reports 8, 1967, pp. 7-11

- ^ Gerhard Rudolf Meyer, On the bronze statuette VA 774 from Toprak-Kale. Research and Reports 8, 1967, 10 (Archaeological Articles). State Museums in Berlin / Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- ^ Reinard Bernbeck, Political Structure and Ideology in Urartu. Archaeological communications from Iran and Turan 35/36, 268

- ^ Gerhard Rudolf Meyer, On the bronze statuette VA 774 from Toprak-Kale. Research and Reports 8, 1967, 8 (Archaeological Contributions). State Museums in Berlin / Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- ↑ CA Burney / GRJ Lawson, Urartian Reliefs at Adilcevaz, on Lake Van, and a Rock Relief from the Karasu, near Birecik. Anatolian Studies 8, 1958, fig. 2

- ↑ Peter Calmeyer, Ursula Seidl: An early Urartian representation of victory . In: Anatolian Studies 33, 1983, p. 107

- ↑ RW Hamilton: The decorated bronze strip from Gushchi. Anatolian Studies 15, 1965, 45

- ^ RW Hamilton: The decorated bronze strip from Guschchi. Anatolian Studies 15, 1965, p. 42.

- ↑ OA Tašyürek: The Urartian belts in the Adana Museum, 1975

- ↑ RW Hamilton: The decorated bronze strip from Gushchi. In: Anatolian Studies 15, 1965, p. 49.

- ^ Gerhard Rudolf Meyer: On the bronze statuette VA 774 from Toprak-Kale . Research and Reports 8, 1967, 8 (Archaeological Contributions). State Museums in Berlin / Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- ↑ BB Piotrovsky, Iskusstvo Urartu, Fig. 43, 18

- ↑ RW Hamilton: The decorated bronze strip from Gushchi . Anatolian Studies 15, 1965, 50

- ^ BB Piotrovsky: Iskusstvo Urartu. Fig. 43,18, BB Piotrovsky: Karmir Blur II, Archaeological Excavations in Armenia. Volume 2, Akademia Nauk Armenjanskoi SSR, Erewan 1950, pp. 37-38, ris. 19, 20.

- ↑ Martirosyan / Mnatsakanyan: Nor-Areschskie Urartskii kolumbarii. Izvestia Akademia Nauk Armenianskoi SSR 10, 1958, pp. 63-84.

- ^ M. Savini: The historical background of the Urartian monument of Meher Kapısı. In: Altan Çilingiroğlu / DH French (ed.): Anatolian Iron Ages 3, British Institute of Archeology at Ankara Monograph 3, Ankara 1994) p. 206.

- ^ Paul Zimansky: Urartian material culture as state assemblage . In: Bulletin American Association of Oriental Research 299, 1995, note 21.

- ↑ 1954: pp. 33-35

- ↑ Altan Çilingiroğlu / Miroslav Salvini, When was the Castle of Ayanıs built and what is the meaning of the word 'Šuri'? Anatolian Iron Ages 4, Proceedings of the Fourth Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium Held at Mersin, 19-23 May 1997. Anatolian Studies 49, 1999, 60

- ↑ Oktay Belli, The Anzaf fortress and the Gods of Urartu. Istanbul 1999, fig. 17

- ^ Reinard Bernbeck, Political Structure and Ideology in Urartu. Archaeological communications from Iran and Turan 35/36, 295

- ↑ Melikisvili

- ^ M. Savini: The historical background of the Urartian monument of Meher Kapısı. In: Altan Çilingiroğlu, DH French (Ed.): Anatolian Iron Ages 3. British Institute of Archeology at Ankara Monograph 3, Ankara 1994, p. 206

- ↑ The British Museum: Bronze figure of a god ( Memento of the original from June 19, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Altan Çilingiroğlu, Mirjo Salvini: When was the Castle of Ayanıs built and what is the meaning of the word 'Šuri'? Anatolian Iron Ages 4, Proceedings of the Fourth Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium Held at Mersin, 19-23 May 1997. Anatolian Studies 49, 1999, p. 56.

- ^ M. Savini: The historical background of the Urartian monument of Meher Kapısı. In: Altan Çilingiroğlu, DH French (Ed.): Anatolian Iron Ages 3. British Institute of Archeology at Ankara Monograph 3, Ankara 1994, p. 205.

- ^ M. Savini: The historical background of the Urartian monument of Meher Kapısı. In: Altan Çilingiroğlu, DH French (Ed.): Anatolian Iron Ages 3. British Institute of Archeology at Ankara Monograph 3, Ankara 1994 p. 207.

- ↑ Altan Çilingiroğlu: Recent excavations at the Urartian fortress of Ayanıs. In: Adam T. Smith, Karen S. Runinson (Eds.): Archeology in the borderlands. Investigations in Caucasia and beyond. Monograph 47, Cotsen Institute of Archeology, UCLA, p. 212.

- ↑ Altan Çilingiroğlu: Recent excavations at the Urartian fortress of Ayanıs. In: Adam T. Smith / Karen S. Runinson (eds.): Archeology in the borderlands. Investigations in Caucasia and beyond. Monograph 47, Cotsen Institute of Archeology, UCLA, p. 212.

- ↑ a b Tuğba Tanyeri-Erdemir: Agency, Innovation, change, continuity: considering the agency of Rusa II in the production of the imperial art and architecture of Urartu in the 7th Century BC. P. 269.

- ^ M. Savini: The historical background of the Urartian monument of Meher Kapısı. 205 ff.

- ^ Reinard Bernbeck, Political Structure and Ideology in Urartu. Archaeological communications from Iran and Turan 35/36, 293

- ↑ Zafer Derin: Potters' Marks of Ayanıs Citadel. Van. Anatolian Studies 49, 1999, p. 90.

- ^ Zafer Derin: The Urartian cremation jars in Van and Elazığ museums. In: A Cilingiroğlu / DH French (Ed.): Anatolian Iron Ages 3. London 1994, p. 46.