Dr. Seuss: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 204.110.45.201 to last version by Tregoweth |

→Early career: notoriety → fame. The former is pejorative. Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|American children's author and cartoonist (1904–1991)}} |

|||

{{sources}} |

|||

{{redirect2|Seuss|Theo Geisel|the surname|Seuss (surname)|the physicist|Theo Geisel (physicist)||Suess (disambiguation){{!}}Suess}} |

|||

{{Infobox Biography |

|||

{{pp-move|small=yes}} |

|||

| subject_name = Dr. Seuss |

|||

{{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} |

|||

| image_name = Ted Geisel NYWTS 2 crop.jpg |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=March 2024}} |

|||

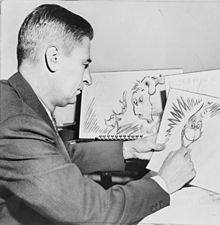

| image_caption = Dr. Seuss in 1957, with some of his books. |

|||

{{Infobox writer |

|||

| date_of_birth = [[March 2]], [[1904]] |

|||

| image = Theodor Seuss Geisel (01037v).jpg |

|||

| place_of_birth = [[Springfield, Massachusetts]], [[USA]] |

|||

| caption = Dr. Seuss in 1957 |

|||

| date_of_death = [[September 24]], [[1991]] |

|||

| pseudonym = {{cslist|<!-- Dr. Seuss -->|Theo LeSieg|Rosetta Stone}} |

|||

| place_of_death = [[La Jolla, California]] |

|||

| birth_name = Theodor Seuss Geisel |

|||

| birth_date = {{Birth date|1904|03|02}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Springfield, Massachusetts]], U.S. |

|||

| death_date = {{Death date and age|1991|09|24|1904|03|02}} |

|||

| death_place = [[San Diego]], California, U.S. |

|||

| education = {{plainlist| |

|||

* [[Dartmouth College]] ([[Bachelor of Arts|AB]]) |

|||

* [[Lincoln College, Oxford]]}} |

|||

| occupation = {{cslist|Children's author|[[political cartoon]]ist|illustrator|poet|animator|filmmaker}} |

|||

| genre = Children's literature<!-- prefer more specific--> |

|||

| spouse = {{plainlist| |

|||

* {{marriage|[[Helen Palmer (writer)|Helen Palmer]]|1927|1967|end=died}} |

|||

* {{marriage|[[Audrey Geisel|Audrey Stone Dimond]]{{wbr}}|1968}}}} |

|||

| signature = Dr Seuss signature.svg |

|||

| signature_alt = Dr. Seuss |

|||

| years_active = 1921–1990<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://www.dartmouth.edu/~library/digital/collections/books/ocm58916242/ocm58916242.html | title=The Beginnings of Dr. Seuss|website=www.dartmouth.edu}}</ref> |

|||

| website = {{URL|seussville.com}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Theodor Seuss Geisel''' ([[March 2]], [[1904]] – [[September 24]], [[1991]]) was a famous [[United States|American]] [[writer]] and [[cartoonist]] best known for his classic [[children's books]] under the [[pen name]] '''Dr. Seuss''', including ''[[The Cat in the Hat]]'', ''[[Green Eggs and Ham]]'', and ''How the Grinch Stole Christmas''. His books have become staples for many children and their parents. Seuss' trademark was his rhyming text and outlandish creatures. He also wrote under the pen names '''Theo. LeSieg''' and '''Rosetta Stone'''. |

|||

'''Theodor Seuss Geisel''' ({{IPAc-en|s|uː|s|_|ˈ|ɡ|aɪ|z|əl|,_|z|ɔɪ|s|_|-|audio=En-us-Geisel.ogg}} {{respell|sooss|_|GHY|zəl|,_|zoyss|_-}};<ref>{{cite web| url = http://www.philnel.com/2013/02/06/seusswrong/| title = How to Mispronounce "Dr. Seuss"| date = February 6, 2013}} ''It is true that the middle name of Theodor Geisel—"Seuss," which was also his mother's maiden name—was pronounced "Zoice" by the family, and by Theodor Geisel himself. So, if you are pronouncing his full given name, saying "Zoice" instead of "Soose" would not be wrong. You'd have to explain the pronunciation to your listener, but you would be pronouncing it as the family did.''</ref><ref name="DICT">[http://www.dictionary.com/browse/seuss "Seuss"]. ''[[Random House Unabridged Dictionary]]''.</ref><ref name=mw>[https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Geisel pronunciation of "Geisel" and "Seuss"] in the [[Webster's Dictionary]]</ref> March 2, 1904 – September 24, 1991)<ref>{{cite web|title=About the Author, Dr. Seuss, Seussville|url=http://www.seussville.com/?home#/author|location=Timeline|access-date=February 15, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131206085230/http://www.seussville.com/?home#/author|archive-date=December 6, 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref> was an American children's author and [[cartoonist]]. He is known for his work writing and illustrating [[Dr. Seuss bibliography|more than 60 books]] under the pen name '''Dr. Seuss''' ({{IPAc-en|s|uː|s|,_|z|uː|s}} {{respell|sooss|,_|zooss}}).<ref name=mw /><ref>{{cite web| url = http://www.philnel.com/2016/03/02/seussfilm/| title = Seuss on New Zealand TV, 1964| date = March 2, 2016}}</ref> His work includes many of the most popular children's books of all time, selling over 600 million copies and being translated into more than 20 languages by the time of his death.<ref name="Reader">{{Cite magazine | title = Unforgettable Dr. Seuss | last= Bernstein |first=Peter W. | magazine= Reader's Digest Australia | year = 1992 | page = 192 | series= Unforgettable | issn= 0034-0375}}</ref> |

|||

==Life and work== |

|||

Geisel was born on March 2, 1904 in [[Springfield, Massachusetts]]. He grew up at 74 Fairfield Street, an ideal location for a youngster, as it was only six blocks from the zoo where his father worked and three blocks from the library. He graduated from [[Dartmouth College]] in [[1925]], where he was a member of [[Sigma Phi Epsilon]] and [[Casque and Gauntlet]], and wrote for the ''[[Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern]]'' humor magazine. |

|||

Geisel adopted the name "Dr. Seuss" as an undergraduate at [[Dartmouth College]] and as a graduate student at [[Lincoln College, Oxford]]. He left Oxford in 1927 to begin his career as an illustrator and cartoonist for ''[[Vanity Fair (magazine)|Vanity Fair]]'', ''[[Life (magazine)|Life]]'', and various other publications. He also worked as an illustrator for [[advertising campaign]]s, including for [[FLIT]] and [[Standard Oil]], and as a [[political cartoon]]ist for the New York newspaper ''[[PM (newspaper)|PM]]''. He published his first children's book ''[[And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street]]'' in 1937. During [[World War II]], he took a brief hiatus from children's literature to illustrate political cartoons, and he worked in the animation and film department of the [[United States Army]]. |

|||

Even at this early stage, Geisel had started using the pen name "Dr. Seuss", as well as his own name. His first work signed as "Dr. Seuss" appeared six months into his work for Judge. Seuss was his mother's maiden name; as an immigrant from Germany, she would have pronounced it more or less as "zoice" (as it is pronounced in German). According to Alexander Liang, who served with Geisel on the staff of the Jack O' Lantern, and was later a professor at Dartmouth: |

|||

After the war, Geisel returned to writing children's books, writing acclaimed works such as ''[[If I Ran the Zoo]]'' (1950), ''[[Horton Hears a Who!]]'' (1955), ''[[The Cat in the Hat]]'' (1957), ''[[How the Grinch Stole Christmas!]]'' (1957), ''[[Green Eggs and Ham]]'' (1960), ''[[One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish]]'' (1960), ''[[The Sneetches and Other Stories]]'' (1961), ''[[The Lorax]]'' (1971), ''[[The Butter Battle Book]]'' (1984), and ''[[Oh, the Places You'll Go!]]'' (1990). He published over 60 books during his career, which have spawned numerous [[Film adaptation|adaptations]], including eleven television specials, five feature films, [[Seussical|a Broadway musical]], and four television series. |

|||

<blockquote>You're wrong as the deuce |

|||

<br> |

|||

And you shouldn't rejoice |

|||

<br> |

|||

If you're calling him Seuss. |

|||

<br> |

|||

He pronounces it Soice.</blockquote> |

|||

He received two [[Primetime Emmy Awards]] for [[Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Children's Program|Outstanding Children's Special]] for ''[[Halloween Is Grinch Night]]'' (1978) and [[Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Animated Program|Outstanding Animated Program]] for ''[[The Grinch Grinches the Cat in the Hat]]'' (1982).<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.emmys.com/shows/search-dr-seuss|title= Dr. Seuss|website= Emmys.com|access-date= March 6, 2021}}</ref> In 1984, he won a [[Pulitzer Prize Special Citation]]. His birthday, March 2, has been adopted as the annual date for [[Read Across America Day|National Read Across America Day]], an initiative focused on reading created by the [[National Education Association]]. |

|||

Today, however, the name is universally pronounced in English with an initial ''s'' sound and rhyming with "juice".<ref>http://german.about.com/library/weekly/aa020401b.htm</ref> Geisel also used the pen name '''Theo. LeSieg''' (Geisel spelled backwards) for books he wrote but others illustrated. |

|||

==Life and career== |

|||

He entered [[Lincoln College, Oxford]], intending to earn a [[doctorate]] in [[literature]]. At [[University of Oxford|Oxford]] he met Helen Palmer, married her in [[1927]], and returned to the [[United States]] without earning the degree. The "Dr." in his pen name is an acknowledgment of his father's unfulfilled hopes that Seuss would earn a doctorate at Oxford. |

|||

=== Early years === |

|||

Geisel was born and raised in [[Springfield, Massachusetts]], the son of Henrietta (''[[Birth name|née]]'' Seuss) and Theodor Robert Geisel.<ref name=ucdsbio>{{cite web|title=The Dr. Seuss Collection|url=http://libraries.ucsd.edu/locations/mscl/collections/the-dr-seuss-collection.html|publisher=UC San Diego|access-date=April 10, 2012|author=Mandeville Special Collections Library|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120420174613/http://libraries.ucsd.edu/locations/mscl/collections/the-dr-seuss-collection.html|archive-date=April 20, 2012}}</ref><ref name="early">{{Cite book |first=Theodor Seuss |last=Geisel |editor-last=Taylor |editor-first=Constance |title=Theodor Seuss Geisel The Early Works of Dr. Seuss |volume=1 |year=2005 |publisher=Checker Book Publishing Group |location=Miamisburg, OH |isbn=978-1-933160-01-6 |page=6 |chapter=Dr. Seuss Biography }}</ref> His father managed the family brewery and was later appointed to supervise Springfield's public park system by Mayor [[John A. Denison]]<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pfIEAAAAYAAJ&q=Theodor%20Robert%20Geisel%20and%20John%20Denison%20mayor&pg=PA13 |title=Municipal register of the city of Springfield (Mass.)|via=Google Books |access-date=December 29, 2013|year=1912 |author=Springfield (Mass.)}}</ref> after the brewery closed because of [[Prohibition in the United States|Prohibition]].<ref name="beer">{{cite web | title=Who Knew Dr. Seuss Could Brew? | work=Narragansett Beer | url=http://www.narragansettbeer.com/2009/12/who-knew-dr-seuss-could-brew | access-date=February 12, 2012 | date=December 17, 2009 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120208223413/http://www.narragansettbeer.com/2009/12/who-knew-dr-seuss-could-brew | archive-date=February 8, 2012 | url-status=dead }}</ref> [[Mulberry Street (Springfield, Massachusetts)|Mulberry Street]] in Springfield, made famous in his first children's book ''[[And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street]]'', is near his boyhood home on Fairfield Street.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.seussinspringfield.org/who-dr-seuss/mulberry-street|title=Mulberry Street|date=March 17, 2015|website=Seuss in Springfield|language=en|access-date=March 4, 2019}}</ref> The family was of [[German Americans|German]] descent, and Geisel and his sister Marnie experienced anti-German prejudice from other children following the outbreak of World War I in 1914.<ref>{{Cite web |date=February 2, 2017 |title=Real Doctor Seuss cartoon from 1941 |url=https://leslie.dartmouth.edu/news/2017/02/real-doctor-seuss-cartoon-1941 |access-date=September 9, 2022 |website=Leslie Center for the Humanities |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|journal = PMLA|volume = 126|issue = 1|pages = 197–202|last=Pease|first=Donald|date=2011|language=en|jstor = 41414092|doi = 10.1632/pmla.2011.126.1.197|title = Dr. Seuss in Ted Geisel's Never-Never Land|s2cid = 161957666}}</ref> Geisel was raised as a [[Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod|Missouri Synod Lutheran]] and remained in the denomination his entire life.<ref name="stltoday2012">{{cite news |url= https://www.stltoday.com/lifestyles/faith-and-values/civil-religion/happy-birthday-dr-seuss/article_e366a878-64b6-11e1-b91f-001a4bcf6878.html |title=Happy birthday, Dr. Seuss! |last=Scholl |first=Travis |work=[[St. Louis Post-Dispatch]] |location=St. Louis |issn= |date=March 2, 2012 |access-date=April 3, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

He began submitting humorous articles and illustrations to [[The Judge|''Judge'']] (a humor magazine), ''[[The Saturday Evening Post]]'', ''[[Life magazine|Life]]'', ''[[Vanity Fair magazine|Vanity Fair]]'', and ''[[Liberty magazine|Liberty]]''. One notable "Technocracy Number" made fun of [[Technocracy Incorporated|Technocracy, Inc.]] and featured satirical rhymes at the expense of [[Frederick Soddy]]. He became nationally famous from his advertisements for [[Flit]], a common insecticide at the time. His slogan, "Quick, Henry, the Flit!" became a popular catchphrase. Geisel supported himself and his wife through the [[Great Depression]] by drawing advertising for [[General Electric]], [[NBC]], [[Standard Oil]], and many other companies. He also wrote and drew a short-lived comic strip called ''[[Hejji]]'' in [[1935]]. |

|||

Geisel attended Dartmouth College, graduating in 1925.<ref>Minear (1999), p. 9.</ref> At Dartmouth, he joined the [[Sigma Phi Epsilon]] fraternity<ref name="ucdsbio" /> and the humor magazine ''[[Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern]]'', eventually rising to the rank of editor-in-chief.<ref name="ucdsbio" /> While at Dartmouth, he was caught drinking [[gin]] with nine friends in his room.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.neh.gov/news/humanities/2009-03/Questions.html |title=Impertient Questions |access-date=June 20, 2009 |last=Nell |first=Phillip |date=March–April 2009 |work=Humanities |publisher=National Endowment for the Humanities }}</ref> At the time, the possession and consumption of alcohol was illegal under Prohibition laws, which remained in place between 1920 and 1933. As a result of this infraction, Dean [[Craven Laycock]] insisted that Geisel resign from all extracurricular activities, including the ''Jack-O-Lantern''.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/drseussmrgeiselb00morg |url-access=registration |page=[https://archive.org/details/drseussmrgeiselb00morg/page/36 36] |quote= |title=Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel: a biography |access-date=September 5, 2010 |last1=Morgan |first1=Judith |last2=Morgan |first2=Neil |isbn=978-0-306-80736-7|year= 1996|publisher=Da Capo Press }}</ref> To continue working on the magazine without the administration's knowledge, Geisel began signing his work with the pen name "Seuss". He was encouraged in his writing by professor of rhetoric W. Benfield Pressey, whom he described as his "big inspiration for writing" at Dartmouth.<ref name="fensch-man-who-was-seuss">{{cite book | last = Fensch | first = Thomas | title = The Man Who Was Dr. Seuss | publisher = New Century Books | location = Woodlands | year = 2001 | isbn = 978-0-930751-11-1 | page = [https://archive.org/details/manwhowasdrseuss0000fens/page/38 38] | url = https://archive.org/details/manwhowasdrseuss0000fens/page/38 }}</ref> |

|||

In [[1936]], while Seuss was again on an ocean voyage to Europe, the rhythm of the ship's engines inspired the poem that became his first book, ''[[And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street]]''. Seuss wrote three more children's books before [[World War II]] (see list of works below), two of which are, atypically for him, in [[prose]]. |

|||

Upon graduating from Dartmouth, he entered Lincoln College, Oxford, intending to earn a [[Doctor of Philosophy]] (D.Phil.) in English literature.<ref name="NYTObit">{{cite news |url= https://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0302.html |title=Dr. Seuss, Modern Mother Goose, Dies at 87 |last=Pace |first=Eric |work=[[The New York Times]] |location=New York City |issn=0362-4331 |date=September 26, 1991 |access-date=November 10, 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Famous Lincoln Alumni|url=https://www.lincoln.ox.ac.uk/Famous-Lincoln-Alumni|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140130131102/http://www.lincoln.ox.ac.uk/Famous-Lincoln-Alumni|url-status=dead|archive-date=January 30, 2014|publisher=Lincoln College, Oxford|access-date=July 26, 2018}}</ref> At Oxford, he met his future wife [[Helen Palmer (author)|Helen Palmer]], who encouraged him to give up becoming an English teacher in favor of pursuing drawing as a career.<ref name="NYTObit" /> She later recalled that "Ted's notebooks were always filled with these fabulous animals. So I set to work diverting him; here was a man who could draw such pictures; he should be earning a living doing that."<ref name="NYTObit" /> |

|||

As World War II began, Dr. Seuss turned to political cartoons, drawing over 400 in two years as editorial cartoonist for the [[left-wing]] [[New York City]] daily newspaper, ''[[PM (newspaper)|PM]]''. Dr. Seuss's political cartoons opposed the viciousness of [[Adolf Hitler|Hitler]] and [[Benito Mussolini|Mussolini]] and were highly critical of isolationists, most notably [[Charles Lindbergh]], who opposed American entry into the war. [http://orpheus.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/pm/1942/20213cs.jpg Some cartoons] depicted all [[Japanese Americans]] as latent traitors or fifth-columnists, while at the same time other cartoons deplored the racism at home against Jews and blacks that harmed the war effort. His cartoons were strongly supportive of President Roosevelt's conduct of the war, combining the usual exhortations to ration and contribute to the war effort with frequent attacks on Congress (especially the Republican Party), parts of the press (such as the [[New York Daily News]] and [[Chicago Tribune]]), and others for criticism of Roosevelt, criticism of aid to the Soviet Union, investigation of suspected Communists, and other offenses that he depicted as leading to disunity and helping the Nazis, intentionally or inadvertently. In [[1942]], Dr. Seuss turned his energies to direct support of the U.S. war effort. First, he worked drawing posters for the [[United States Department of the Treasury|Treasury Department]] and the [[United States War Production Board|War Production Board]]. Then, in [[1943]], he joined the [[US Army|Army]] and was commander of the Animation Dept of the [[First Motion Picture Unit]] of the [[United States Army Air Forces]], where he wrote films that included ''Your Job in Germany'', a [[1945]] propaganda film about peace in Europe after World War II, ''Design for Death'', a study of [[Japanese culture]] that won the [[Academy Awards|Academy Award]] for Best [[Documentary film|Documentary]] in [[1947]], and the ''[[Private Snafu]]'' series of adult army training films. While in the Army, he was awarded the [[Legion of Merit]]. Dr. Seuss's non-military films from around this time were also well-received; ''[[Gerald McBoing-Boing]]'' won the Academy Award for Best Short Subject (Animated) in [[1950]]. |

|||

===Early career=== |

|||

Despite his numerous awards, Dr. Seuss never won the [[Caldecott Medal]] nor the [[Newbery Medal|Newbery]]. Three of his titles were chosen as Caldecott runners-up (now referred to as Caldecott Honor books): ''McElligot's Pool'' (1947), ''Bartholomew and the Oobleck'' (1949), and ''If I Ran the Zoo'' (1950). |

|||

Geisel left Oxford without earning a degree and returned to the United States in February 1927,<ref>Morgan (1995), p. 57</ref> where he immediately began submitting writings and drawings to magazines, book publishers, and advertising agencies.<ref>Pease (2010), pp. 41–42</ref> Making use of his time in Europe, he pitched a series of cartoons called ''Eminent Europeans'' to ''Life'' magazine, but the magazine passed on it. His first nationally published cartoon appeared in the July 16, 1927, issue of ''[[The Saturday Evening Post]]''. This single $25 sale encouraged Geisel to move from Springfield to New York City.<ref>Cohen (2004), pp. 72–73</ref> Later that year, Geisel accepted a job as writer and illustrator at the humor magazine ''[[Judge (magazine)|Judge]]'', and he felt financially stable enough to marry Palmer.<ref>Morgan (1995), pp. 59–62</ref> His first cartoon for ''Judge'' appeared on October 22, 1927, and Geisel and Palmer were married on November 29. Geisel's first work signed "Dr. Seuss" was published in ''Judge'' about six months after he started working there.<ref>Cohen (2004), p. 86</ref> |

|||

In early 1928, one of Geisel's cartoons for ''Judge'' mentioned [[FLIT|Flit]], a common bug spray at the time manufactured by [[Esso|Standard Oil of New Jersey]].<ref>Cohen (2004), p. 83</ref> According to Geisel, the wife of an advertising executive in charge of advertising Flit saw Geisel's cartoon at a hairdresser's and urged her husband to sign him.<ref>Morgan (1995), p. 65</ref> Geisel's first Flit ad appeared on May 31, 1928, and the campaign continued sporadically until 1941. The campaign's catchphrase "Quick, Henry, the Flit!" became a part of popular culture. It spawned a song and was used as a punch line for comedians such as [[Fred Allen]] and [[Jack Benny]]. As Geisel gained fame for the Flit campaign, his work was in demand and began to appear regularly in magazines such as ''Life'', ''[[Liberty (general interest magazine)|Liberty]]'' and ''[[Vanity Fair (magazine)|Vanity Fair]]''.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

After the war, Dr. Seuss and his wife moved to [[La Jolla, San Diego, California|La Jolla, California]]. Returning to children's books, he wrote what many consider to be his finest works, including such favorites as ''If I Ran the Zoo'', (1950), ''Scrambled Eggs Super!'' (1953), ''On Beyond Zebra!'' (1955), ''If I Ran the Circus'' (1956), and ''[[How the Grinch Stole Christmas!]]'' (1957). |

|||

The money Geisel earned from his advertising work and magazine submissions made him wealthier than even his most successful Dartmouth classmates.<ref name=":0">Pease (2010), pp. 48–49</ref> The increased income allowed the Geisels to move to better quarters and to socialize in higher social circles.<ref>Pease (2010), p. 49</ref> They became friends with the wealthy family of banker [[Frank A. Vanderlip]]. They also traveled extensively: by 1936, Geisel and his wife had visited 30 countries together. They did not have children, neither kept regular office hours, and they had ample money. Geisel also felt that traveling helped his creativity.<ref>Morgan (1995), p. 79</ref> |

|||

At the same time, an important development occurred that influenced much of Seuss's later work. In May [[1954]], ''[[Life magazine|Life]]'' magazine published a report on [[illiteracy]] among school children, which concluded that children were not learning to read because their books were boring. Accordingly, Seuss's publisher made up a list of 400 words he felt were important and asked Dr. Seuss to cut the list to 250 words and write a book using only those words. Nine months later, Seuss, using 220 of the words given to him, completed ''[[The Cat in the Hat]]''. This book was a ''tour de force''—it retained the drawing style, verse rhythms, and all the imaginative power of Seuss's earlier works, but because of its simplified vocabulary could be read by beginning readers. A rumor exists, that in [[1960]], [[Bennett Cerf]] bet Dr. Seuss $50 that he couldn't write an entire book using only fifty words. The result was supposedly ''[[Green Eggs and Ham]]''. The additional rumor that Cerf never paid Seuss the $50 has never been proven and is most likely untrue. These books achieved significant international success and remain very popular. |

|||

Geisel's success with the Flit campaign led to more advertising work, including for other Standard Oil products like Essomarine boat fuel and Essolube Motor Oil and for other companies like the [[Ford Motor Company]], [[NBC Radio Network]], and Holly Sugar.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Dr. Seuss|last=Levine|first=Stuart P.|date=2001|publisher=Lucent Books|isbn=978-1560067481|location=San Diego, CA|oclc=44075999|url=https://archive.org/details/drseuss0000levi}}</ref> His first foray into books, ''[[The Pocket Book of Boners|Boners]]'', a collection of children's sayings that he illustrated, was published by [[Viking Press]] in 1931. It topped ''[[The New York Times]]'' non-fiction bestseller list and led to a sequel, ''More Boners'', published the same year. Encouraged by the books' sales and positive critical reception, Geisel wrote and illustrated an [[Alphabet book|ABC book]] featuring "very strange animals" that failed to interest publishers.<ref>Morgan (1995), pp. 71–72</ref> |

|||

Dr. Seuss went on to write many other children's books, both in his new simplified-vocabulary manner (sold as "[[Beginner Books]]") and in his older, more elaborate style. In 1982 Dr. Seuss wrote "[[Hunches in Bunches]]". The Beginner Books were not easy for Seuss, and reportedly he labored for months crafting them. |

|||

In 1936, Geisel and his wife were returning from an ocean voyage to Europe when the rhythm of the ship's engines inspired the poem that became his first children's book: ''And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street''.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://thepeel.appstate.edu/fall2010/blog/id/23 |title=Ten Things You May Not Have Known About Dr. Seuss |first=Andrew |last=Baker |publisher=The Peel |date=March 3, 2010 |access-date=April 9, 2012}}</ref> Based on Geisel's varied accounts, the book was rejected by between 20 and 43 publishers.<ref>Nel (2004), pp. 119–21</ref><ref name="lurie">{{cite book|last=Lurie|first=Alison|title=The Cabinet of Dr. Seuss|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BEkB2J-Wb4sC&q=mulberry%20street%20seuss&pg=PA68|work=Popular Culture: An Introductory Text|access-date=October 30, 2013|isbn=978-0879725723|year=1992|publisher=Popular Press }}</ref> According to Geisel, he was walking home to burn the manuscript when a chance encounter with an old Dartmouth classmate led to its publication by [[Vanguard Press]].<ref>Morgan (1995), pp. 79–85</ref> Geisel wrote four more books before the US entered World War II. This included ''[[The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins]]'' in 1938, as well as ''[[The King's Stilts]]'' and ''[[The Seven Lady Godivas]]'' in 1939, all of which were in prose, atypically for him. This was followed by ''[[Horton Hatches the Egg]]'' in 1940, in which Geisel returned to the use of verse. |

|||

At various times Seuss also wrote books for adults that used the same style of verse and pictures: ''[[The Seven Lady Godivas]]''; ''[[Oh, The Places You'll Go!]]''; and ''[[You're_Only_Old_Once!_:_A_Book_for_Obsolete_Children|You're Only Old Once]]''. |

|||

===World War II-era work=== |

|||

During a very difficult illness, Dr. Seuss' wife, Helen Palmer Geisel, committed [[suicide]] on October 23, 1967. Seuss married Audrey Stone Dimond on June 21, 1968. Seuss himself died, following several years of illness, in [[La Jolla, San Diego, California|La Jolla, California]] on [[September 24]], 1991. |

|||

[[File:The Goldbrick.ogv|thumb|"The Goldbrick", Private Snafu episode written by Seuss, 1943]] |

|||

As World War II began, Geisel turned to political cartoons, drawing over 400 in two years as editorial cartoonist for the left-leaning New York City daily newspaper, ''[[PM (newspaper)|PM]]''.<ref>[[Richard Minear|Richard H. Minear]], ''[[Dr. Seuss Goes to War|Dr. Seuss Goes to War: The World War II Editorial Cartoons of Theodor Seuss Geisel]]'' p. 16. {{ISBN|1-56584-704-0}}</ref> Geisel's political cartoons, later published in ''[[Dr. Seuss Goes to War]]'', denounced [[Adolf Hitler]] and [[Benito Mussolini]] and were highly critical of non-interventionists ("isolationists"), such as [[Charles Lindbergh]], who opposed US entry into the war.<ref name="Goes to War">{{cite book |last=Minear |first=Richard H. |title=Dr. Seuss Goes to War: The World War II Editorial Cartoons of Theodor Seuss Geisell |year=1999 |publisher=[[The New Press]] |location=New York City |isbn=978-1-56584-565-7 |page=[https://archive.org/details/drseussgoestowar00mine/page/9 9] |title-link=Dr. Seuss Goes to War }}</ref> One cartoon<ref name=signalpic>{{Cite web |author=Dr. Seuss|title=Waiting for the Signal from Home|date=February 13, 1942|url=https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/object/bb5222708w}}</ref> depicted [[Japanese Americans]] being handed TNT in anticipation of a "signal from home", while other cartoons deplored the racism at home against [[Jews]] and blacks that harmed the war effort.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Nel|first=Philip|date=2007|title=Children's Literature Goes to War: Dr. Seuss, P. D. Eastman, Munro Leaf, and the Private SNAFU Films (1943–46)|journal=The Journal of Popular Culture|language=en|volume=40|issue=3|page=478|doi=10.1111/j.1540-5931.2007.00404.x|s2cid=162293411 |issn=1540-5931|quote=For example, Seuss's support of civil rights for African Americans appears prominently in the PM cartoons he created before joining ‘‘Fort Fox.''}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.jewishpress.com/indepth/front-page/dr-seuss-and-the-jews/2016/02/03/|title=Dr. Seuss And The Jews|last=Singer|first=Saul Jay|date=February 3, 2016 |language=en-US|access-date=December 23, 2019}}</ref> His cartoons were strongly supportive of [[Franklin D. Roosevelt|President Roosevelt]]'s handling of the war, combining the usual exhortations to ration and contribute to the war effort with frequent attacks on Congress<ref>{{cite web|title=Congress|url=http://libraries.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/Congress.html|work=Dr. Seuss Went to War: A Catalog of Political Cartoons by Dr. Seuss|publisher=UC San Diego|access-date=April 10, 2012|author=Mandeville Special Collections Library|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120512120750/http://libraries.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/Congress.html|archive-date=May 12, 2012|url-status=dead}}</ref> (especially the [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican Party]]),<ref>{{cite web|title=Republican Party|url=http://libraries.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/RepublicanParty.html|work=Dr. Seuss Went to War: A Catalog of Political Cartoons by Dr. Seuss|publisher=UC San Diego|access-date=April 10, 2012|author=Mandeville Special Collections Library|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120512121216/http://libraries.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/RepublicanParty.html|archive-date=May 12, 2012|url-status=dead}}</ref> parts of the press (such as the ''[[New York Daily News]]'', ''[[Chicago Tribune]]'' and ''[[Washington Times-Herald]]''),<ref>Minear (1999), p. 191.</ref> and others for criticism of Roosevelt, criticism of aid to the Soviet Union,<ref name=OurWarLoad>{{cite web|title=February 19|url=http://libraries.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/pm/1942/20219cs.jpg|work=Dr. Seuss Went to War: A Catalog of Political Cartoons by Dr. Seuss|publisher=UC San Diego|access-date=April 10, 2012|author=Mandeville Special Collections Library|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120417213625/http://libraries.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/pm/1942/20219cs.jpg|archive-date=April 17, 2012|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name=LifeLine>{{cite web|title=March 11|url=http://libraries.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/pm/1942/20311cs.jpg|work=Dr. Seuss Went to War: A Catalog of Political Cartoons by Dr. Seuss|publisher=UC San Diego|access-date=April 10, 2012|author=Mandeville Special Collections Library|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120417213615/http://libraries.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/pm/1942/20311cs.jpg|archive-date=April 17, 2012|url-status=dead}}</ref> investigation of suspected Communists,<ref>Minear (1999), pp. 190–91.</ref> and other offences that he depicted as leading to disunity and helping the Nazis, intentionally or inadvertently. |

|||

In 1942, Geisel turned his energies to direct support of the U.S. war effort. First, he worked drawing posters for the [[United States Department of the Treasury|Treasury Department]] and the [[War Production Board]]. Then, in 1943, he joined the Army as a [[Captain (United States O-3)|captain]] and was commander of the Animation Department of the [[First Motion Picture Unit]] of the [[United States Army Air Forces]], where he wrote films that included ''[[Your Job in Germany]]'', a 1945 propaganda film about peace in Europe after World War II; ''[[Our Job in Japan]]'' and the ''[[Private Snafu]]'' series of adult army training films. While in the Army, he was awarded the [[Legion of Merit]].<ref>Morgan (1995), p. 116</ref> ''Our Job in Japan'' became the basis for the commercially released film ''Design for Death'' (1947), a study of [[Culture of Japan|Japanese culture]] that won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature Film.<ref>Morgan (1995), pp. 119–20</ref> ''[[Gerald McBoing-Boing]]'' (1950) was based on an original story by Seuss and won the [[Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film#1950s|Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film]].<ref>{{cite news|last=Ellin|first=Abby|title=The Return of Gerald McBoing Boing?|newspaper=[[The New York Times]]|date=October 2, 2005|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2005/10/02/arts/television/the-return-of-gerald-mcboing-boing.html}}</ref> |

|||

In 2002 the [[Dr. Seuss Memorial|Dr. Seuss National Memorial Sculpture Garden]] opened in his birthplace of [[Springfield, Massachusetts]]; it features sculptures of Dr. Seuss and of many of his characters. |

|||

== |

===Later years=== |

||

After the war, Geisel and his wife moved to the [[La Jolla]] community of [[San Diego]], California, where he returned to writing children's books. He published most of his books through [[Random House]] in North America and [[William Collins, Sons]] (later [[HarperCollins]]) internationally. He wrote many, including such favorites as ''[[If I Ran the Zoo]]'' (1950), ''[[Horton Hears a Who!]]'' (1955), ''[[If I Ran the Circus]]'' (1956), ''[[The Cat in the Hat]]'' (1957), ''[[How the Grinch Stole Christmas!]]'' (1957), and ''[[Green Eggs and Ham]]'' (1960). He received numerous awards throughout his career, but he won neither the [[Caldecott Medal]] nor the [[Newbery Medal]]. Three of his titles from this period were, however, chosen as Caldecott runners-up (now referred to as Caldecott Honor books): ''[[McElligot's Pool]]'' (1947), ''Bartholomew and the Oobleck'' (1949), and ''If I Ran the Zoo'' (1950). Dr. Seuss also wrote the [[musical film|musical]] and [[fantasy film]] ''[[The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T.]]'', which was released in 1953. The movie was a critical and financial failure, and Geisel never attempted another feature film.{{Citation needed|date=July 2023}} During the 1950s, he also published a number of illustrated short stories, mostly in ''[[Redbook]]'' magazine. Some of these were later collected (in volumes such as ''The Sneetches and Other Stories'') or reworked into independent books (''If I Ran the Zoo''). A number have never been reprinted since their original appearances. |

|||

Dr. Seuss wrote most of his books in a verse form that in the terminology of [[meter (poetry)|metrics]] would be characterized as [[anapaest|anapest]]ic [[tetrameter]], a meter employed also by [[George Gordon Byron, Lord Byron|Lord Byron]] and other poets of the English literary canon.(It is also the meter of the famous Christmas poem ''[[A Visit From St. Nicholas]]''.) Abstractly, anapestic tetrameter consists of four rhythmic units (anapests), each composed of two weak beats followed by one strong, schematized below: |

|||

In May 1954, ''[[Life (magazine)|Life]]'' published a report on [[Literacy|illiteracy]] among school children which concluded that children were not learning to read because their books were boring. William Ellsworth Spaulding was the director of the education division at [[Houghton Mifflin]] (he later became its chairman), and he compiled a list of 348 words that he felt were important for first-graders to recognize. He asked Geisel to cut the list to 250 words and to write a book using only those words.<ref name="new yorker 1960">{{cite magazine |title= Profiles: Children's Friend |last=Kahn |first=E. J. Jr. |author-link=Ely Jacques Kahn, Jr. |url=http://archives.newyorker.com/?i=1960-12-17#folio=046 |magazine=[[The New Yorker]] |publisher=[[Condé Nast|Condé Nast Publications]] |date=December 17, 1960 |access-date=September 20, 2008 }}</ref> Spaulding challenged Geisel to "bring back a book children can't put down".<ref name="new yorker 2002">{{cite magazine |title=Cat People: What Dr. Seuss Really Taught Us |last=Menand |first=Louis |author-link=Louis Menand |url=https://www.newyorker.com/archive/2002/12/23/021223crat_atlarge?currentPage=all |magazine=[[The New Yorker]] |publisher=[[Condé Nast|Condé Nast Publications]] |date=December 23, 2002 |access-date=September 16, 2008 }}</ref> Nine months later, Geisel completed ''[[The Cat in the Hat]]'', using 236 of the words given to him. It retained the drawing style, verse rhythms, and all the imaginative power of Geisel's earlier works but, because of its simplified vocabulary, it could be read by beginning readers. ''The Cat in the Hat'' and subsequent books written for young children achieved significant international success and they remain very popular today. For example, in 2009, ''Green Eggs and Ham'' sold 540,000 copies, ''The Cat in the Hat'' sold 452,000 copies, and ''[[One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish]]'' (1960) sold 409,000 copies—all outselling the majority of newly published children's books.<ref name="Publishers Weekly 2010">{{cite news|url=http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/childrens/childrens-book-news/article/42533-children-s-bestsellers-2009-the-reign-continues.html |title=The Reign Continues |publisher=Publishes Weekly |first=Diane |last=Roback |date=March 22, 2010 |access-date=April 9, 2012}}</ref> |

|||

: x x X x x X x x X x x X |

|||

Geisel went on to write many other children's books, both in his new simplified-vocabulary manner (sold as [[Beginner Books]]) and in his older, more elaborate style. |

|||

Often, the first weak syllable is omitted, or an additional weak syllable is added at the end. A typical line (the first line of ''If I Ran the Circus'') is: |

|||

In 1955, Dartmouth awarded Geisel an honorary [[doctorate of Humane Letters]], with the citation: |

|||

: In ALL the whole TOWN the most WONderful SPOT |

|||

{{blockquote|Creator and fancier of fanciful beasts, your affinity for flying elephants and man-eating mosquitoes makes us rejoice you were not around to be Director of Admissions on Mr. Noah's ark. But our rejoicing in your career is far more positive: as author and artist you singlehandedly have stood as St. George between a generation of exhausted parents and the demon dragon of unexhausted children on a rainy day. There was an inimitable wriggle in your work long before you became a producer of motion pictures and animated cartoons and, as always with the best of humor, behind the fun there has been intelligence, kindness, and a feel for humankind. An Academy Award winner and holder of the Legion of Merit for war film work, you have stood these many years in the academic shadow of your learned friend Dr. Seuss; and because we are sure the time has come when the good doctor would want you to walk by his side as a full equal and because your College delights to acknowledge the distinction of a loyal son, Dartmouth confers on you her Doctorate of Humane Letters.<ref>"Honorary Degrees Awarded to Eleven", ''Dartmouth Alumni Magazine'' [https://archive.dartmouthalumnimagazine.com/article/1955/7/honorary-degrees-awarded-to-eleven July 1955], p. 18-19</ref>}} |

|||

Geisel joked that he would now have to sign "Dr. Dr. Seuss".<ref>"A Day of Ceremony", ''Dartmouth Medicine: The Magazine of the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth'', [https://dartmed.dartmouth.edu/fall12/html/day_of_ceremony/ Fall 2012]</ref> His wife was ill at the time, so he delayed accepting it until June 1956.<ref>Tanya Anderson, ''Dr. Seuss (Theodor Geisel)'', {{isbn|143814914X}}, n.p.</ref> |

|||

Geisel's wife Helen had a long struggle with illnesses. On October 23, 1967, Helen died by suicide. Eight months later, on June 21, 1968, Geisel married [[Audrey Geisel|Audrey Dimond]] with whom he had reportedly been having an affair.<ref name=wife>{{cite news |first=Joyce |last=Wadler |title=Public Lives: Mrs. Seuss Hears a Who, and Tells About It |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2000/11/29/nyregion/public-lives-mrs-seuss-hears-a-who-and-tells-about-it.html |work=[[The New York Times]] |date=November 29, 2000 |access-date=May 28, 2008}}</ref> Although he devoted most of his life to writing children's books, Geisel had no children of his own, saying of children: "You have 'em; I'll entertain 'em."<ref name=wife /> Audrey added that Geisel "lived his whole life without children and he was very happy without children."<ref name=wife /> Audrey oversaw Geisel's estate until her death on December 19, 2018, at the age of 97.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/audrey-geisel-caretaker-of-the-dr-seuss-literary-estate-dies-at-97/2018/12/21/188c5810-054e-11e9-9122-82e98f91ee6f_story.html|title=Audrey Geisel, caretaker of the Dr. Seuss literary estate, dies at 97|newspaper=[[The Washington Post]]|date=December 19, 2018|access-date=December 22, 2018}}</ref> |

|||

Seuss generally maintained this meter quite strictly, until late in his career, when he was no longer able to maintain strict rhythm in all lines. The consistency of his meter was one of his hallmarks; the many imitators and parodists of Seuss are often unable to write in strict anapestic tetrameter, or are unaware that they should, and thus sound clumsy in comparison with the original. |

|||

Geisel was awarded an honorary doctorate of Humane Letters (L.H.D.) from [[Whittier College]] in 1980.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.whittier.edu/alumni/poetnation/honorary|title=Honorary Degrees {{!}} Whittier College|website=www.whittier.edu|access-date=January 28, 2020}}</ref> He also received the [[Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal]] from the [[Association for Library Service to Children|professional children's librarians]] in 1980, recognizing his "substantial and lasting contributions to children's literature". At the time, it was awarded every five years.<ref name=wilder>{{Primary source inline|date=July 2023}} |

|||

Seuss also wrote verse in [[trochaic]] [[tetrameter]], an arrangement of four units each with a strong followed by a weak beat. |

|||

[http://www.ala.org/alsc/awardsgrants/bookmedia/wildermedal/wilderpast ''Laura Ingalls Wilder Award, Past winners'']. [[Association for Library Service to Children]] (ALSC) – [[American Library Association]] (ALA). [http://www.ala.org/alsc/awardsgrants/bookmedia/wildermedal/wilderabout ''About the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award'']. Retrieved June 17, 2013.</ref>{{Primary source inline|date=July 2023}} He won a [[Pulitzer Prize Special Citations and Awards|special Pulitzer Prize]] in 1984 citing his "contribution over nearly half a century to the education and enjoyment of America's children and their parents".<ref name=pulitzer>[http://www.pulitzer.org/bycat/Special-Awards-and-Citations "Special Awards and Citations"]. The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved December 2, 2013.</ref>{{Primary source inline|date=July 2023}} |

|||

==Illness, death, and posthumous honors== |

|||

: X x X x X x X x |

|||

[[File:DrSeussStatue.jpg|thumb|left|upright|alt=Bronze statue of Dr. Seuss and his character The Cat in the Hat outside the library|Bronze statue of Dr. Seuss and his character The Cat in the Hat outside the [[Geisel Library]] in San Diego]] |

|||

Geisel died of [[cancer]] on September 24, 1991, at his home in the La Jolla community of San Diego at the age of 87.<ref name="NYTObit" /><ref>{{cite news|url=https://articles.latimes.com/1991-09-26/news/mn-3873_1_seuss-books|title= Theodor Geisel Dies at 87; Wrote 47 Dr. Seuss Books, Author: His last new work, 'Oh, the Places You'll Go!' has proved popular with executives as well as children|last=Gorman|first=Tom|author2=Miles Corwin|date=September 26, 1991|work=Los Angeles Times|access-date=March 2, 2012}}</ref> His ashes were scattered in the Pacific Ocean. On December 1, 1995, four years after his death, [[University of California, San Diego]]'s University Library Building was renamed [[Geisel Library]] in honor of Geisel and Audrey for the generous contributions that they made to the library and their devotion to improving literacy.<ref>{{cite web|title=About the Geisel Library Building|url=http://libraries.ucsd.edu/about/us/geisel-building.html|publisher=UC San Diego|access-date=April 10, 2012|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140102200755/https://libraries.ucsd.edu/about/us/geisel-building.html|archive-date=January 2, 2014}}</ref> |

|||

In 2002, the [[Dr. Seuss Memorial|Dr. Seuss National Memorial Sculpture Garden]] opened in [[Springfield, Massachusetts]], featuring sculptures of Geisel and of many of his characters.{{Citation needed|date=July 2023}} In 2017, the [[Amazing World of Dr. Seuss Museum]] opened next to the [[Dr. Seuss Memorial|Dr. Seuss National Memorial Sculpture Garden]] in the [[Quadrangle (Springfield, Massachusetts)|Springfield Museums Quadrangle]].{{Citation needed|date=July 2023}} In 2008, Dr. Seuss was inducted into the [[California Hall of Fame]].{{Citation needed|date=July 2023}} In 2004, U.S. children's librarians established the annual [[Geisel Award|Theodor Seuss Geisel Award]] to recognize "the most distinguished American book for beginning readers published in English in the United States during the preceding year". It should "demonstrate creativity and imagination to engage children in reading" from [[pre-kindergarten]] to [[second grade]].<ref>[http://www.ala.org/alsc/awardsgrants/bookmedia/geiselaward "Welcome to the (Theodor Seuss) Geisel Award home page!"]. ALSC. ALA.<br /> |

|||

An example is the title (and first line) of ''One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish''. The formula for trochaic meter permits the final weak position in the line to be omitted, which facilitates the construction of rhymes. |

|||

[http://www.ala.org/alsc/awardsgrants/bookmedia/geiselaward/geiselabout "Theodor Seuss Geisel Award"]. ALSC. ALA. Retrieved June 17, 2013.</ref>{{Primary source inline|date=July 2023}} On April 4, 2012, the Dartmouth Medical School was renamed the [[Geisel School of Medicine|Audrey and Theodor Geisel School of Medicine]] in honor of their many years of generosity to the college.<ref>{{cite news|title=Dartmouth Names Medical School in Honor of Audrey and Theodor Geisel|url=http://geiselmed.dartmouth.edu/news/2012/04/04_geisel.shtml|access-date=April 9, 2012|newspaper=Geisel School of Medicine|date=April 4, 2012}}</ref>{{Primary source inline|date=July 2023}} Dr. Seuss has a star on the [[Hollywood Walk of Fame]] at the 6500 block of [[Hollywood Boulevard]].<ref>{{cite news|url=http://projects.latimes.com/hollywood/star-walk/dr-seuss/ |title=Dr. Seuss – Hollywood Star Walk |first1=Miles |last1=Corwin |first2=Tom |last2=Gorman |newspaper=Los Angeles Times |date=September 26, 1991 |access-date=April 9, 2012}}</ref> |

|||

In 2012, a [[Seuss (crater)|crater]] on the planet Mercury was named after Geisel.<ref>{{cite web |url = http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/Feature/14972 |title = Seuss |publisher = [[IAU]]/[[NASA]]/[[USGS]] |work = Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature |accessdate = August 19, 2023}}</ref> |

|||

Seuss generally maintained trochaic meter only for brief passages, and for longer stretches typically mixed it with [[iambic]] tetrameter: |

|||

==Pen names== |

|||

: x X x X x X x X |

|||

Geisel's most famous pen name is regularly pronounced {{IPAc-en|s|uː|s}},<ref name="DICT" /> an [[Anglicisation|anglicized]] pronunciation of his German name (the standard German pronunciation is {{IPA-de|ˈzɔʏ̯s}}). He himself noted that it rhymed with "voice" (his own pronunciation being {{IPAc-en|s|ɔɪ|s}}). Alexander Laing, one of his collaborators on the ''[[Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern]]'',<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://now.dartmouth.edu/2010/06/and-think-it-happened-dartmouth|title=And to Think That It Happened at Dartmouth|website=now.dartmouth.edu|year=2010|access-date=May 12, 2016|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160412195551/http://now.dartmouth.edu/2010/06/and-think-it-happened-dartmouth|archive-date=April 12, 2016}}</ref> wrote of it: |

|||

{{poemquote|You're wrong as the deuce |

|||

which is easier to write. Thus, for example, the magicians in ''Bartholomew and the Oobleck'' make their first appearance chanting in trochees (thus resembling the witches of [[William Shakespeare|Shakespeare's]] ''[[Macbeth]]''): |

|||

And you shouldn't rejoice |

|||

If you're calling him Seuss. |

|||

He pronounces it Soice<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.anapsid.org/aboutmk/seuss.html |title=Theodor Seuss Geisel: Author Study |last=Kaplan |first=Melissa |work=anapsid.org |date=December 18, 2009 |access-date=December 2, 2011}} ([http://www.anapsid.org/pdf/seuss.pdf Source in PDF].)</ref> (or Zoice)<ref>{{cite web|title=About the Author, Dr. Seuss, Seussville|url=http://www.seussville.com/?home#/author|location=Biography|access-date=February 15, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131206085230/http://www.seussville.com/?home#/author|archive-date=December 6, 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref>}} |

|||

Geisel switched to the anglicized pronunciation because it "evoked a figure advantageous for an author of children's books to be associated with—[[Mother Goose]]"<ref name="new yorker 2002" /> and because most people used this pronunciation. He added the "Doctor (abbreviated Dr.)" to his pen name because his father had always wanted him to practice medicine.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://thefw.com/things-you-didnt-know-about-dr-seuss/ |title=15 Things You Probably Didn't Know About Dr. Seuss |date=March 2, 2012 |publisher=Thefw.com |access-date=December 16, 2013}}</ref> |

|||

: Shuffle, duffle, muzzle, muff |

|||

For books that Geisel wrote and others illustrated, he used the pen name "Theo LeSieg", starting with ''[[I Wish That I Had Duck Feet]]'' published in 1965. "LeSieg" is "Geisel" spelled backward.<ref>Morgan (1995), p. 219</ref> Geisel also published one book under the name Rosetta Stone, 1975's ''Because a Little Bug Went Ka-Choo!!'', a collaboration with [[Michael K. Frith]]. Frith and Geisel chose the name in honor of Geisel's second wife Audrey, whose maiden name was Stone.<ref>Morgan (1995), p. 218</ref> |

|||

then switch to iambs for the oobleck spell: |

|||

==Political views== |

|||

: Go make the oobleck tumble down |

|||

{{Main|Political messages of Dr. Seuss}} |

|||

: On every street, in every town! |

|||

Geisel was a liberal [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democrat]] and a supporter of President [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]] and the [[New Deal]].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Glanton |first1=Dahleen |title=Column: The liberal Dr. Seuss probably would have thought 'cancel culture' was bunk |url=https://www.chicagotribune.com/columns/dahleen-glanton/ct-glanton-dr-seuss-cancel-culture-20210308-v24jhwzsebcxhnjhhgrhajwmtq-story.html |website=chicagotribune.com |date=March 8, 2021 |publisher=Tribune Media Company |access-date=April 15, 2023}}</ref> His early political cartoons show a passionate opposition to fascism, and he urged action against it both before and after the U.S. entered World War II.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Macdonald |first=Fiona |title=The surprisingly radical politics of Dr Seuss |url=https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20190301-the-surprisingly-radical-politics-of-dr-seuss |access-date=April 12, 2022 |website=www.bbc.com |language=en}}</ref> His cartoons portrayed the fear of communism as overstated, finding greater threats in the [[House Committee on Unamerican Activities]] and those who threatened to cut the U.S.'s "life line"<ref name=LifeLine /> to the USSR and Stalin, whom he once depicted as a [[Porter (carrier)|porter]] carrying "our war load".<ref name="OurWarLoad" /> |

|||

[[File:Seuss cartoon.png|thumb|Dr. Seuss 1942 cartoon with the caption 'Waiting for the Signal from Home']] |

|||

In ''Green Eggs and Ham'', Sam-I-Am generally speaks in trochees, and the exasperated character he proselytizes replies in iambs. |

|||

Geisel supported the [[internment of Japanese Americans]] during World War II in order to prevent possible sabotage.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Macdonald |first1=Fiona |title=The surprisingly radical politics of Dr Seuss |url=https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20190301-the-surprisingly-radical-politics-of-dr-seuss |website=bbc.com |publisher=BBC |access-date=April 15, 2023}}</ref> Geisel explained his position: |

|||

While most of Seuss's books are either uniformly anapestic or iambic-trochaic, a few mix triple and double rhythms. Thus, for instance, ''Happy Birthday to You'' is generally written in anapestic tetrameter, but breaks into iambo-trochaic meter for the "Dr. Derring's singing herrings" and "Who-Bubs" episodes. |

|||

{{blockquote|But right now, when the Japs are planting their hatchets in our skulls, it seems like a hell of a time for us to smile and warble: "Brothers!" It is a rather flabby battle cry. If we want to win, we've got to kill Japs, whether it depresses [[John Haynes Holmes]] or not. We can get palsy-walsy afterward with those that are left.<ref>Minear (1999), p. 184.</ref>}} |

|||

Dr. Seuss also inspired other authors to write in his story way and taught kids many things like reading. |

|||

After the war, Geisel overcame his feelings of animosity and {{nowrap|re-examined}} his view, using his book ''[[Horton Hears a Who!]]'' (1954) as an [[allegory]] for the American post-war [[occupation of Japan]], as well as dedicating the book to a Japanese friend.<ref>{{Cite magazine |last=Markovitz |first=Adam |date=March 14, 2008 |title=''Horton Hears a Who!'' metaphors |url=https://ew.com/article/2008/03/14/horton-hears-who-metaphors/ |access-date=October 26, 2023 |magazine=Entertainment Weekly |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=August 20, 2014 |title=Dr. Seuss Draws Anti-Japanese Cartoons During WWII, Then Atones with Horton Hears a Who! |url=https://www.openculture.com/2014/08/dr-seuss-draws-racist-anti-japanese-cartoons-during-ww-ii.html |access-date=October 26, 2023 |website=Open Culture |language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

==Artwork== |

|||

Geisel converted a copy of one of his famous children's books, ''[[Marvin K. Mooney Will You Please Go Now!]]'', into a [[polemic]] shortly before the end of the 1972–1974 [[Watergate scandal]], in which U.S. president [[Richard Nixon]] resigned, by replacing the name of the main character everywhere that it occurred.<ref name=Buchwald /> "Richard M. Nixon, Will You Please Go Now!" was published in major newspapers through the [[Column (periodical)|column]] of his friend [[Art Buchwald]].<ref name=Buchwald>{{cite news |first=Art |last=Buchwald |author-link=Art Buchwald |title=Richard M. Nixon Will You Please Go Now! |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/04/19/AR2006041901099.html |newspaper=[[The Washington Post]] |page=B01 |date=July 30, 1974 |access-date=September 17, 2008 }}</ref> |

|||

Seuss's earlier artwork often employed the shaded texture of pencil drawings or watercolors, but in children's books of the postwar period he generally employed the starker medium of pen and ink, normally using just black, white, and one or two colors. Later books such as ''The Lorax'' used more colors. |

|||

The line "a person's a person, no matter how small" from ''Horton Hears a Who!'' has been used widely as a slogan by the [[Anti-abortion movements|pro-life]] movement in the United States. Geisel and later his widow Audrey objected to this use; according to her attorney, "She doesn't like people to hijack Dr. Seuss characters or material to front their own points of view."<ref name = ally>{{cite news|url=https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=88189147|title=In 'Horton' Movie, Abortion Foes Hear an Ally|date=March 14, 2008|work=NPR|access-date=January 7, 2019}}</ref> In the 1980s, Geisel threatened to sue an anti-abortion group for using this phrase on their stationery, according to his biographer, causing them to remove it.<ref name = who>{{cite news|url=https://abcnews.go.com/Entertainment/story?id=4454256&page=1|title=Horton's Who: The Unborn?|last=Baram|first=Marcus|date=March 17, 2008|work=ABC News|access-date=January 7, 2019}}</ref> The attorney says he never discussed abortion with either of them,<ref name = ally/> and the biographer says Geisel never expressed a public opinion on the subject.<ref name = who/> After Seuss's death, Audrey gave financial support to [[Planned Parenthood]].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://catholicexchange.com/who-would-dr-seuss-support|title=Who Would Dr. Seuss Support?|date=January 2, 2004|work=Catholic Exchange|access-date=January 7, 2019}}</ref> |

|||

Seuss's figures are often rounded and somewhat droopy. This is true, for instance, of the faces of the Grinch and of the Cat in the Hat. It is also true of virtually all buildings and machinery that Seuss drew: although these objects abound in straight lines in real life, Seuss carefully avoided straight lines in drawing them (in fact, he never drew a completely straight line at any part of any of his works). For buildings, this could be accomplished in part through choice of architecture. For machines, for example, ''If I Ran the Circus'' includes a droopy hoisting crane and a droopy steam calliope. |

|||

===In his children's books=== |

|||

Seuss evidently enjoyed drawing architecturally elaborate objects. His endlessly varied (but never rectilinear) palaces, ramps, platforms, and free-standing stairways are among his most evocative creations. Seuss also drew elaborate imaginary machines, of which the Audio-Telly-O-Tally-O-Count, from ''Dr. Seuss's Sleep Book'', is one example. Seuss also liked drawing outlandish arrangements of feathers or fur, for example, the 500th hat of ''Bartholomew Cubbins'', the tail of ''Gertrude McFuzz'', and the pet for girls who like to brush and comb, in ''One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish''. |

|||

Geisel made a point of not beginning to write his stories with a moral in mind, stating that "kids can see a moral coming a mile off." He was not against writing about issues, however; he said that "there's an inherent moral in any story",<ref>{{cite magazine |last=Bunzel |first=Peter |date=April 6, 1959 |title=The Wacky World of Dr. Seuss Delights the Child—and Adult—Readers of His Books |magazine=[[Life (magazine)|Life]] | location=Chicago | issn=0024-3019 | oclc =1643958 | quote =Most of Geisel's books point a moral, though he insists that he never starts with one. 'Kids,' he says, 'can see a moral coming a mile off and they gag at it. But there's an inherent moral in any story.' }}</ref> and he remarked that he was "subversive as hell."<ref>{{cite book |last=Cott |first=Jonathan |title=Pipers at the Gates of Dawn: The Wisdom of Children's Literature |edition=Reprint |year=1984 |publisher=[[Random House]] |location=New York City |isbn=978-0-394-50464-3 |oclc=8728388 |chapter=The Good Dr. Seuss |chapter-url-access=registration |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/pipersatgatesofd00cott }}</ref> |

|||

Geisel's books express his views on a wide variety of social and political issues: ''[[The Lorax]]'' (1971), about environmentalism and [[anti-consumerism]]; ''[[The Sneetches and Other Stories|The Sneetches]]'' (1961), about [[racial equality]]; ''[[The Butter Battle Book]]'' (1984), about the [[arms race]]; ''[[Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories|Yertle the Turtle]]'' (1958), about [[Adolf Hitler]] and [[anti-authoritarianism]]; ''[[How the Grinch Stole Christmas!]]'' (1957), criticizing the [[economic materialism]] and [[consumerism]] of the Christmas season; and ''[[Horton Hears a Who!]]'' (1954), about anti-[[isolationism]] and [[Internationalism (politics)|internationalism]].<ref name="new yorker 2002" /><ref name="hayley">{{cite web |title=Interview with filmmaker Ron Lamothe about ''The Political Dr. Seuss'' |url=http://www.mfh.org/lamotheinterview/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070916044241/http://www.mfh.org/lamotheinterview/ |author=Wood, Hayley and Ron Lamothe (interview) |work=MassHumanities eNews |publisher=Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities |date=August 2004 |archive-date=September 16, 2007 |access-date=September 16, 2008 }}</ref> |

|||

Seuss's images often convey motion vividly. He was fond of a sort of "voilà" gesture, in which the hand flips outward, spreading the fingers slightly backward with the thumb up; this is done by Ish, for instance, in ''One Fish, Two Fish'' when he creates fish (who perform the gesture themselves with their fins), in the introduction of the various acts of ''If I Ran the Circus'', and in the introduction of the Little Cats in ''The Cat in the Hat Comes Back''. Seuss also follows the cartoon tradition of showing motion with lines, for instance in the sweeping lines that accompany Sneelock's final dive in ''If I Ran the Circus''. Cartoonist's lines are also used to illustrate the action of the senses (sight, smell, and hearing) in ''The Big Brag'' and even of thought, as in the moment when the Grinch conceives his awful idea. |

|||

=== Retired books === |

|||

Interestingly enough, there is some thought that Seuss's Imagery, especially that of ''The Cat in the Hat'' was a metaphor for "sweeping out" communism and ''cleaning out'' the "red". |

|||

Seuss's work for children has been criticized for unconscious racist themes.<ref name="diversity">{{cite web |author1=Katie Ishizuka|author2= Ramón Stephens |date=2019 |title=The Cat is Out of the Bag: Orientalism, Anti-Blackness, and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss's Children's Books |publisher=Research on Diversity in Youth Literature |url=https://sophia.stkate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1050&context=rdyl}}</ref> Dr. Seuss Enterprises, the organization that owns the rights to the books, films, TV shows, stage productions, exhibitions, digital media, licensed merchandise, and other strategic partnerships, announced on March 2, 2021, that it will stop publishing and licensing six books. The publications include ''[[And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street]]'' (1937), ''[[If I Ran the Zoo]]'' (1950), ''[[McElligot's Pool]]'' (1947), ''[[On Beyond Zebra!]]'' (1955), ''[[Scrambled Eggs Super!]]'' (1953) and ''[[The Cat's Quizzer]]'' (1976). According to the organization, the books "portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong" and are no longer being published.<ref>{{cite news |last=Feldman |first=Kate |url=https://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/ny-dr-seuss-books-canceled-20210302-7piolxczljgpve6iwxi32v3uyu-story.html |title=Six Dr. Seuss books to stop being published over 'hurtful and wrong' portrayals |work=[[New York Daily News]] |date=March 2, 2021 |access-date=March 2, 2021 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|access-date=April 11, 2023|author=Dr. Seuss Enterprises|date=March 2, 2021|language=en|publisher=Dr. Seuss Enterprises|quote=Today, on Dr. Seuss’s Birthday, Dr. Seuss Enterprises celebrates reading and also our mission of supporting all children and families with messages of hope, inspiration, inclusion, and friendship. We are committed to action. To that end, Dr. Seuss Enterprises, working with a panel of experts, including educators, reviewed our catalog of titles and made the decision last year to cease publication and licensing of the following titles: And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, If I Ran the Zoo, McElligot’s Pool, On Beyond Zebra!, Scrambled Eggs Super!, and The Cat’s Quizzer. These books portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong. Ceasing sales of these books is only part of our commitment and our broader plan to ensure Dr. Seuss Enterprises’s catalog represents and supports all communities and families.|title=Statement from Dr. Seuss Enterprises|url=https://www.seussville.com/statement-from-dr-seuss-enterprises/}}<!-- auto-translated by Module:CS1 translator --></ref> |

|||

==Style== |

|||

===Recurring images=== |

|||

Seuss's early work in advertising and editorial cartooning produced sketches that received more perfect realization later on in the children's books. Often, the expressive use to which Seuss put an image later on was quite different from the original. The examples below are from the website of the [http://orpheus.ucsd.edu/speccoll/seusscoll.html Mandeville Special Collections Library] of the [[University of California, San Diego]]. |

|||

===Poetic meters=== |

|||

*An [http://orpheus.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/pm/10716cs.jpg editorial cartoon of July 16, 1941] depicts a [[whale]] resting on the top of a mountain, as a [[parody]] of American [[isolationism|isolationists]], especially [[Charles Lindbergh]]. This was later rendered (with no apparent political content) as the Wumbus of ''On Beyond Zebra'' (1955). Seussian whales (cheerful and balloon-shaped, with long eyelashes) also occur in ''McElligot's Pool'', ''If I Ran the Circus'', and other books. |

|||

Geisel wrote most of his books in [[anapestic tetrameter]], a [[Meter (poetry)|poetic meter]] employed by many poets of the English literary canon. This is often suggested as one of the reasons that Geisel's writing was so well received.<ref>{{cite magazine |last1=Mensch |first1=Betty |last2=Freeman |first2=Alan |title=Getting to Solla Sollew: The Existentialist Politics of Dr. Seuss |year=1987 |magazine=[[Tikkun (magazine)|Tikkun]] |page=30 |quote=In opposition to the conventional—indeed, hegemonic—iambic voice, his metric triplets offer the power of a more primal chant that quickly draws the reader in with relentless repetition.}}</ref><ref name="of-sneetches">{{cite book |editor-last=Fensch |editor-first=Thomas |title=Of Sneetches and Whos and the Good Dr. Seuss |year=1997 |publisher=[[McFarland & Company]] |location=[[Jefferson, North Carolina]] |isbn=978-0-7864-0388-2 |oclc= 37418407}}</ref> |

|||

===Artwork=== |

|||

*[http://orpheus.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/pm/10519cs.jpg Another editorial cartoon from 1941] shows a long cow with many legs and udders, representing the conquered nations of Europe being milked by [[Adolf Hitler]]. This later became the Umbus of ''On Beyond Zebra''. |

|||

{{more citations needed|section|date=September 2017}}<!--first part of section has no references--> |

|||

[[File:Ted Geisel NYWTS.jpg|thumb|left|Geisel at work on a drawing of the [[Grinch]] for ''[[How the Grinch Stole Christmas!]]'' in 1957]] |

|||

Geisel's early artwork often employed the shaded texture of pencil drawings or [[watercolor]]s, but in his children's books of the postwar period, he generally made use of a starker medium—pen and ink—normally using just black, white, and one or two colors. His later books, such as ''[[The Lorax]],'' used more colors. |

|||

*The tower of turtles in [http://orpheus.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/pm/1942/20321cs.jpg this editorial cartoon from 1941] prefigures a similar tower in ''Yertle the Turtle''. |

|||

Geisel's style was unique—his figures are often "rounded" and somewhat droopy. This is true, for instance, of the faces of [[the Grinch]] and [[the Cat in the Hat]]. Almost all his buildings and machinery were devoid of straight lines when they were drawn, even when he was representing real objects. For example, ''[[If I Ran the Circus]]'' shows a droopy hoisting crane and a droopy [[steam calliope]]. |

|||

*Seuss's earliest [[elephant]]s were for advertising and had somewhat [http://orpheus.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dsads/bizpostcards/postcardD101.shtml wrinkly ears], much as real elephants do. With ''And to Think that I Saw it on Mulberry Street'' (1937) and ''Horton Hatches the Egg'' (1940), the ears became more stylized, somewhat like [[angel]] wings and thus appropriate to the saintly Horton. During World War II, the elephant image appeared as an emblem for [[India]] in [http://orpheus.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/India.html four editorial cartoons]. Horton and similar elephants appear frequently in the postwar children's books. |

|||

Geisel evidently enjoyed drawing architecturally elaborate objects, and a number of his motifs are identifiable with structures in his childhood home of [[Springfield, Massachusetts|Springfield]], including examples such as the [[onion domes]] of its [[:File:Main Street Springfield Mass 1905.jpg|Main Street]] and his family's brewery.<ref>{{cite web|website=Hell's Acres|archive-date=February 19, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190219015335/http://hellsacres.blogspot.com/2015/01/seussified-springfield.html|url=http://hellsacres.blogspot.com/2015/01/seussified-springfield.html|title=Seussified Springfield|date=January 1, 2015}} |

|||

*While drawing advertisements for [[Flit]], Seuss became adept at drawing [http://orpheus.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dsads/flit/flit.jpg insects with huge stingers], shaped like a gentle S-curve and with a sharp end that included a rearward-pointing barb on its lower side. Their facial expressions depict gleeful malevolence. These insects were later rendered in an editorial cartoon as a [http://orpheus.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/pm/1942/21111cs.jpg swarm of Allied aircraft] (1942), and later still as the Sneedle of ''On Beyond Zebra''. |

|||

* {{cite web|website=Springfield Museums|archive-date=August 19, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160819083645/https://springfieldmuseums.org/press-release/and-to-think-that-he-saw-it-in-springfield/|url=https://springfieldmuseums.org/press-release/and-to-think-that-he-saw-it-in-springfield/|date=August 2, 2011|title=And to Think that He Saw It in Springfield!}}</ref> His endlessly varied but never rectilinear palaces, ramps, platforms, and free-standing stairways are among his most evocative creations. Geisel also drew complex imaginary machines, such as the ''Audio-Telly-O-Tally-O-Count'', from ''[[Dr. Seuss's Sleep Book]]'', or the "most peculiar machine" of Sylvester McMonkey McBean in ''[[The Sneetches]]''. Geisel also liked drawing outlandish arrangements of feathers or fur: for example, the 500th hat of ''[[Bartholomew Cubbins]]'', the tail of ''[[Gertrude McFuzz]]'', and the pet for girls who like to brush and comb, in ''One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish''. |

|||

Geisel's illustrations often convey motion vividly. He was fond of a sort of "voilà" gesture in which the hand flips outward and the fingers spread slightly backward with the thumb up. This motion is done by Ish in ''One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish'' when he creates fish (who perform the gesture with their fins), in the introduction of the various acts of ''If I Ran the Circus'', and in the introduction of the "Little Cats" in ''[[The Cat in the Hat Comes Back]]''. He was also fond of drawing hands with interlocked fingers, making it look as though his characters were twiddling their thumbs. |

|||

==Politics== |

|||

[[Image:10425cs.jpg|thumb|300px|1941 cartoon by Dr. Seuss depicting [[Charles Lindbergh]].]] |

|||

His early political cartoons show a passionate opposition to [[fascism]], and he urged Americans to oppose it, both before and after the entry of the United States into World War II. (By contrast, his cartoons tended to regard the fear of [[communism]] as overstated, finding the greater threat in the [[Dies Committee]] and those who threatened to cut America's [http://orpheus.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/pm/1942/20311cs.jpg "life line"] to Stalin and Soviet Russia, the ones [http://orpheus.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dspolitic/pm/1942/20219cs.jpg carrying "our war load"].) Seuss' cartoons also called attention to the early stages of [[the Holocaust]] and denounced discrimination in America against [[Black (people)|black people]] and [[Jew]]s. Seuss himself experienced anti-semitism: in his college days, he was refused entry into certain circles because of a (mis)perception that he was Jewish. Seuss' racist treatment of the Japanese and of Japanese Americans<ref>[http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/1aa/1aa291.htm The Political Dr. Seuss] Springfield Library and Museums Association</ref>, mentioned above, has struck many readers as a strange moral blind spot in a generally idealistic man. |

|||

Geisel also follows the [[cartoon]] tradition of showing [[motion lines|motion with lines]], like in the sweeping lines that accompany Sneelock's final dive in ''If I Ran the Circus''. Cartoon lines are also used to illustrate the action of the senses—sight, smell, and hearing—in ''The Big Brag,'' and lines even illustrate "thought", as in the moment when the Grinch conceives his awful plan to ruin Christmas. |

|||

In 1948, after living and working in Hollywood for years, Seuss moved to La Jolla, California. It is said that when he went to register to vote in La Jolla, some [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] friends called him over to where they were registering voters, but Ted said, "You my friends are over there, but I am going over here [to the Democratic registration]." Seuss had since been a lifelong [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democrat]]. |

|||

==Adaptations== |

|||

Seuss' children's books also express his commitment to social justice as he perceived it: |

|||

{{More citations needed section|date=July 2023}} |

|||

[[File:Seuss Landing.jpg|thumb|right|[[Universal Islands of Adventure#Seuss Landing|Seuss Landing]] at [[Islands of Adventure]] in [[Orlando, Florida]]]] |

|||

*''[[The Lorax]]'' (1971), though told in full-tilt Seussian style, strikes many readers as fundamentally an [[environmentalism|environmentalist]] tract. It is the tale of a ruthless and greedy industrialist (the "[[Once-ler]]") who so thoroughly destroys the local environment that he ultimately puts his own company out of business. The book is striking for being told from the viewpoint (generally bitter, self-hating, and remorseful) of the Once-ler himself. In [[1989]], an effort was made by [[lumber]]ing interests in [[Laytonville, California]], to have the book banned from local school libraries, on the grounds that it was unfair to the lumber industry. |

|||

For most of his career, Geisel was reluctant to have his characters marketed in contexts outside of his own books. However, he did permit the creation of several animated cartoons, an art form in which he had gained experience during World War II, and he gradually relaxed his policy as he aged. |

|||

The first adaptation of one of Geisel's works was an [[Horton Hatches the Egg (film)|animated short film]] based on ''[[Horton Hatches the Egg]]'', animated at [[Leon Schlesinger Productions]] in 1942 and directed by [[Bob Clampett]]. As part of [[George Pal]]'s [[Puppetoons]] theatrical cartoon series for [[Paramount Pictures]], two of Geisel's works were adapted into stop-motion films by George Pal. The first, ''[[The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins]]'', was released in 1943.<ref>{{cite web |title=The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins |url= https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0035602/ |website=IMDb |access-date=March 3, 2017}}</ref> The second, ''[[And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street#film|And to Think I Saw It on Mulberry Street]]'', with a title slightly altered from [[And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street|the book's]], was released in 1944.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Big Cartoon Database |url= https://www.bcdb.com/cartoon/36555-And-To-Think-I-Saw-It-On-Mulberry-Street |access-date=March 3, 2017}}{{dead link|date=January 2024|bot=medic}}{{cbignore|bot=medic}}</ref> Both were nominated for an [[Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film|Academy Award for "Short Subject (Cartoon)"]]. |

|||

*''[[The Sneetches]]'' (1961) is commonly seen as a satire of racial discrimination. |

|||

In 1966, Geisel authorized eminent cartoon artist [[Chuck Jones]]—his friend and former colleague from the war—to make a cartoon version of ''[[How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (TV special)|How the Grinch Stole Christmas!]]'' The cartoon was narrated by [[Boris Karloff]], who also provided the voice of the Grinch. It is often broadcast as an annual [[Christmas television special]]. Jones directed an adaptation of ''[[Horton Hears a Who! (TV special)|Horton Hears a Who!]]'' in 1970 and produced an adaptation of ''[[The Cat in the Hat (TV special)|The Cat in the Hat]]'' in 1971. |

|||

*''[[The Butter Battle Book]]'' (1984) written in Seuss's old age, is both a parody and denunciation of the [[nuclear arms race]]. It was attacked by conservatives as endorsing [[moral relativism]] by implying that the difference between the sides in the Cold War were no more than the choice between how to butter one's bread. |

|||

From 1972 to 1983, Geisel wrote six animated specials that were produced by [[DePatie-Freleng]]: ''[[The Lorax (TV special)|The Lorax]]'' (1972); ''[[Dr. Seuss on the Loose]]'' (1973); ''[[The Hoober-Bloob Highway]]'' (1975); ''[[Halloween Is Grinch Night]]'' (1977); ''[[Pontoffel Pock, Where Are You?]]'' (1980); and ''[[The Grinch Grinches the Cat in the Hat]]'' (1982). Several of the specials won multiple [[Emmy Award|Emmy]] Awards. A Soviet [[Paint-on-glass animation|paint-on-glass-animated]] short film was made in 1986 called ''[[Welcome (1986 film)|Welcome]]'', an adaptation of ''Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose''. The last adaptation of Geisel's work before he died was ''[[The Butter Battle Book]]'', a television special based on the book of the same name, directed by [[Ralph Bakshi]]. A television film titled ''[[In Search of Dr. Seuss]]'' was released in 1994, which adapted many of Seuss's stories. |

|||

*''[[The Zax]]'' can be seen as a parody of all political hardliners. |

|||