Amarna letters

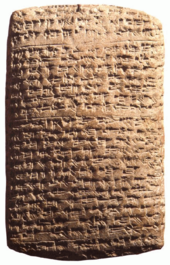

The so-called Amarna letters from the Amarna archive are an extensive find of clay tablets in Akkadian cuneiform in the palace archives of Pharaoh Akhenaten from his residence Achet-Aton , today's Tell el Amarna in Egypt.

Finding circumstances

The Amarna letters are named after where they were found el-Amarna , after which they are usually abbreviated with EA. There are different reports about the exact circumstances of the find. Fellach probably found the clay tablets with cuneiform in 1887 when they were looking for antiquity, digging for marl to fertilize their fields, or removing bricks from the ruins for reuse. The first finds are likely to have attracted more "treasure hunters". In the process, some pieces were intentionally or involuntarily broken and destroyed, or they had been in this condition since ancient times. A little more than 300 of the tablets ended up in the antiques trade in Cairo via various channels and from there to numerous European museums and the Egyptian Museum in Cairo .

From November 1891 to March 1892 WM Flinders Petrie carried out systematic excavations on the debris field of Amarna , uncovering many of the city's buildings. In a building east of the Royal Palace, south of the great and near the north corner of the small temple (which Petrie referred to as number 19), he found more cuneiform tablets and a small clay cylinder with cuneiform writing. He identified the building as a royal archive, as stamped bricks were marked: the location of the records of the king's palace . The other Amarna letters were almost certainly found in a room to the south-east of this house. Petrie's findings were concentrated in two garbage pits near this room. Since the pits were partly under the walls of the south-eastern room, the letters were probably disposed of here before the building was constructed.

Of the 22 clay tablet fragments from the Petrie excavation, only seven contained relevant letters. From 1907 to 1979, a further 24 panels came to light. Of the 382 tables known today, 32 are not letters or the associated inventory lists , but myths and epics from the Mesopotamian written culture, syllable tables , lexical texts, a history of Hurrian origin and a list of Egyptian words in syllabic cuneiform and their equivalents in Babylonian .

Jörgen A. Knudtzon divided the Amarna letters into two parts: First the international correspondence, then the correspondence with the Egyptian vassals. He allocated those of the international correspondence counterclockwise to the respective empires: Babylonia (EA 1-14), Assyria (EA 15-16), Mitanni (EA 17.19-30), Arzawa (EA 31-32), Alašija (EA 33-40) and Hittite Empire (EA 41-44). The second and far larger group of letters he assigned to the vassals from north to south. Within the assigned areas, they are arranged chronologically according to palaeographic criteria and internal logic.

language

The letters are written in cuneiform and, with a few exceptions, in Old Babylonian, a dialect of the Akkadian language , but also reveal Canaanite influence. The translation of the letters caused extraordinary difficulties. The language is the product of a long development in diplomacy , almost nothing is known about before the Amarna period . The Amarna letters contain logograms that had long been replaced by new ones in the Babylonian writing schools (at the same time during the Amarna period), and old orthographies were retained, sometimes mixed with modern ones. This means that only a few writers in antiquity should have mastered this lingua franca of diplomats, and it is all the more difficult today to translate it: “It is not enough for a budding translator to be able to speak Akkadian, he must also be a specialist in Hebrew and Ugaritic , but above all must he knows the letters so well that he knows what to expect from each of their authors. "

The translations by the Norwegian linguist for Semitic languages Jörgen Alexander Knudtzon from 1915 and by William L. Moran from 1987 are trend-setting.

chronology

The relative and absolute chronology of the Amarna letters also still causes great difficulties for research. The letters were not dated and only the kings of Mitanni, Babylon and Assyria named Pharaoh. The King of Alašija addressed the "King of Egypt" and so did the vassals, if they did not choose other terms such as "My God" or "The Sun".

An important clue is the hieratic note by a scribe on EA 23. It gives the 36th year of Amenhotep III's reign as the date of receipt . on. The other letters to Amenhotep III. most likely incorporate into the previous five years, so the archive begins around the 30th year of this king.

The question of the end of the Amarna correspondence is much more difficult to answer. This is generally related to the chronological difficulties at the end of the Amarna period . The decisive question is whether Tutankhamun still received letters in Amarna or whether the text corpus ends earlier. The hieratic inscription of a year 12 (Akhenaten) on EA 254 is generally regarded as the terminus post quem , but Moran does not rule out a reading as year 32 (Amenhotep III). In addition, the mentions of Meritoton instead of Nefertiti are a clue.

Already under Semenchkare the restoration of the old, pre-Amarna period conditions and a compromise restoration of the Amun cult began. Tutankhamun also initially continued this “gentle” return to the old faith. At some point he introduced a more uncompromising restoration by changing his name from Tutankhaton to Tutankhamun and giving up the residence in Amarna in favor of Memphis . According to Erik Hornung, " Aton and his high priest still play an important role in the vessel inscriptions of the 2nd year of reign".

Rolf Krauss, on the other hand, assumes that Amarna was probably left in Tutankhamun's first year:

“In any case, the city was given up between the grape harvests of Tutankhamun's 1st and 2nd year, as there are wine jar seals from the 1st year, but no seals from the 2nd year from Amarna. The year [1], which is probably to be added to the restoration stele of Tutankhamun, speaks in favor of leaving the city after the 1st grape harvest [...]. "

In addition, the letter EA 9 was addressed to a king named Nibhuruia. From a philological point of view, an equation with Tutankhamun's throne name Nb-ḫprw-Rˁ is most likely, but Akhenaten's throne name Nfr-ḫprw-Rˁ cannot be completely ruled out (see in this context the Dahamunzu affair: Nibhururia ).

Edward Fay Campbell thinks it is possible that Tutankhamun still received letters EA 9, 210 and 170 in Amarna, but that they were sent there rather “by mistake”. The assumption that Tutankhamun is the addressee of EA 9 leads, according to Hornung, to such unlikely conclusions that the equation of Nibhuruia with Akhenaten should certainly not be rashly ruled out. He also assumes that only those letters were left in Amarna that were no longer up-to-date when the residence was moved. According to Hornung, all of this indicates that the Amarna archive ends soon after Akhenaten's 12th year of reign, before or at the beginning of Semenchkare's co-reign.

William Moran again organizes the international correspondence as follows:

- Babylonia: The Last Years Amenhotep III. until the late years of Akhenaten or until the first year of Tutankhamun (if EA 9 was actually addressed to Tutankhamun).

- Assyria: Until Akhenaten's late years, or later.

- Mitanni: year 30 Amenhotep III. until Akhenaten's early years (assuming that there was no coregence)

- Arzawa: Time of Amenhotep III.

The international correspondence

In the late Bronze Age, the region around the eastern Mediterranean was divided among a few great powers who saw themselves as members of an exclusive "club" that is often referred to in literature as the "Great Powers Club". Accordingly, the kings of the great empires addressed each other as "brothers" in diplomatic correspondence. The Amarna letters are part of a well-established system of diplomacy, but nothing has been archaeologically preserved from earlier times.

Babylonia (EA 1-14)

In the 19th century BC Chr. Was Babylon still a state among others in Mesopotamia. Hammurapi I of Babylon managed to unite the region under his leadership - half a century before the Hittite Empire established itself in central Anatolia. Hammurapi successors were able to maintain the rule for 150 years before the Hittite raid by I. Mursili ended. Mursili soon lost interest and the Kassites took over the rule. Perhaps they were allied with Mursili.

The Kassite king Kadašman-Enlil I led with Amenophis III. Correspondence. In EA 1, Kadašman-Enlil I. refers to a letter that Amenhotep III gave him. has sent. Amenhotep III demands a daughter of Kadašman-Enlil I for marriage, although he is already married to his sister, who gave him his father. Kadašman-Enlil I sent messengers to the Egyptian court, but they could no longer identify his sister. Amenhotep presented them with the daughter of some other Asian because his sister had already died. Amenophis replied: "If your daughter had really died, what was the point of hiding it?" In addition, the messengers were some "nobodies" that the princess did not even know.

Kadašman-Enlil I. agrees to the "bridal trade" (EA 2) and when the desired daughter is of marriageable age, he announced that she should pick up a delegation (EA 3). He also complains that he received only poor quality gold, Amenhotep III. hold back his messengers and he was not invited to the festival. Kadašman-Enlil also demands an Egyptian daughter, to which Amenophis replies: “Since time immemorial, no daughter of the king of Egypt has been given to anyone.” (EA 4) The Babylonian king would have been content with the daughter of another Egyptian, as he said, with parentage it is not so precise with him. But even this wish is denied to him and so he insists on valuable gifts. Amenophis sends him furniture for the new royal palace in Babylon and promises more gifts when the princess arrives (EA 5).

Burna-buriaš II. , The successor of Kadašman-Enlil I, assures Amenophis III. his friendship and that gifts should continue to be exchanged (EA 6). Under Amenhotep IV, however, Egyptian-Babylonian relations cooled. Amenhotep IV did not ask about Burna-buriaš II's well-being when he was sick. The two kings apparently no longer need each other, but want to maintain the friendship. (EA 7)

Nevertheless, Burna-buriaš II asks for a lot of gold, which he urgently needs for a temple building (EA 7, EA 9), which he finally receives, albeit in very inferior quality (EA 10). In EA 8 Burna-buriaš II asks Amenhotep IV for damages for an attack on a trade embassy that was attacked in Canaan, which belongs to Egypt. He warns: “Execute the men who killed my servants and avenge their blood. And if you don't execute them, they will kill again, be it one of my caravans or your own messengers, and so the messengers between us will be cut off. "

EA 8 and 9 also bear witness to the rise of Assyria under the ancient oriental great powers. Burna-buriaš regards the Egyptian-Assyrian rapprochement with concern and tries to prevent them:

“As for the Assyrians, my vassals, I did not send them to you. Why did they come to your country on their own initiative? If you love me they shouldn't do business. Send them away to me empty-handed! "

Amenhotep IV also desires a Babylonian princess. After the princess destined for him died of an epidemic, he was assured of another. He sends an (allegedly) poor escort of only five cars to pick them up. Under Amenhotep III. the envoy was accompanied by 3,000 men (EA 11). Even in a later phase there are apparently the initiation of dynastic marriages, as the inventories on dowry and bride price (EA 13 and 14) show.

Assyria (EA 15-16)

In the 2nd millennium BC Assyrian merchants established a trading network in Eastern and Central Anatolia. The economic successes made the emergence of the ancient Assyrian empire possible, a city-state with the center in Aššur on the banks of the Tigris , north of the mouth of the small Zab. Around 1760, the Babylonian king was able to conquer the empire and subsequently control it. When Babylon was conquered by the Hittites about 170 years later, the region increasingly fell to the rising Mitanni. The Mitanni king Sauštatar sacked the city of Aššur. Assyria almost completely disappeared from the map. Only a few royal dynasties survived, which formed the basis for the revival to great power, especially after the destruction of the Mitanni by the Hittites. Already Eriba-Adad I (1380 v. BC-1354 v. Chr.) Freed Assyria from the Mitanni and Ashur-uballit I. (1353 v. BC-1318 v. Chr.) Independence has consolidated and took over parts of the Mitannic domain.

The two Amarna letters EA 15 and 16 attest to this rise in power of the early Central Assyrian rulers. The first letter is a careful initial contact by Aššur-uballiṭ I:

“So far, my predecessors had not sent any messages; today (but) I am sending you a message. [...] Do not stop the messenger I sent you to see (you and your country). He should see (you and your country) and (then) leave for me. He should see your attitude and the attitude of your country and (then) leave to me. "

In the second letter, the Assyrian king appears much more self-confident. He calls himself "Great King" and addresses the Egyptian king as "brother". He complains about the stingy gift of the Egyptian king and demands a lot of gold, because “Gold is in your country (like) earth; you collect it (simply from the ground) ”. In addition, his ambassadors are being held back from returning from Egypt.

Mitanni (EA 17-30)

With the end of the Egyptian interventions against the Mitanni after the reign of Thutmose III. their expansion efforts increased under Saustatara I, especially against Assyria, where they culminated in the sack of the city of Assur. The area south of Alalach , which was controlled by Kadesh , they were also able to bring into their sphere of influence through an alliance. This revealed efforts towards the Mediterranean, but the region also served as a buffer against Egypt. However, the Hittite king Tudhalija I set Saustatara's ambitions clear. The Kizzuwatna region could be attached to the Hittite Empire. Thus access to Syria was also in Hittite hands.

Artatama I , the successor Saustatara I, took up negotiations with Egypt in the face of the Hittite threat to prevent Egyptian interference. A peace agreement with the Mitanni was also in Egypt's interests. This created a dynastic connection between the two realms. In the letter EA 29 to Akhenaten, Tušratta von Mitanni mentions the marriage of Thutmosis IV with a daughter of Artatama and that the pharaoh had to ask for the hand of the Mitanni princess seven times before the Mitanni king consented to the marriage. This fact was already seen as a sign of the increasing power of the Mitanni empire. Others saw it as pure diplomatic banter. It is likely that Tušratta, in retrospect, wanted to show the one-sided connection in a better light.

With this connection between Artatama and Thutmose IV the situation in the Middle East changed. Egypt limited itself to the control of the area up to Amurru , Kadesch and Ugarit . As in Hatti with Arnuwanda I. There was a weak king, the Mitanni kingdom was able to consolidate.

Amenhotep III maintains good relations with Šuttarna II , successor of Artatama, which are strengthened by another marriage: In the 10th year of the reign, Amenophis III marries. a daughter of Šuttarna named Giluḫepa.

At some point the diplomatic traffic breaks off and will only resume around the 30th year of Amenhotep III's reign. recorded by the young King Tušratta of Mitanni. Tušratta recapitulates the events in EA 17: After the death of Suttarna II, his son Artaššumara succeeded the Mitannic throne, who was murdered by an officer named Uthi. Tušratta reports that he destroyed Artaššumara's murderers. Now he is trying to get back to his father's good relationships.

The role of the Hittites in the Mitannian throne chaos remains unclear. Perhaps they tried to set up an anti-king with Artaššumara, because at the same time there is reports of an attack by Šuppiluliuma I on Mitanni. At first, the Suppiluliuma's advance against the Mitanni was unsuccessful. It only led to the revival of the Egyptian-Mitannian alliance.

In EA 18, Tušratta asks for a solemn embassy to recognize him as king. Apparently the letter was preceded by an unsuccessful request. The recognition of the Egyptian king seems to be important to him in order to strengthen his position. The lengthy negotiations about the marriage of Tušratta's daughter, Taduchepa , with Amenophis III follow in the next few letters . (EA 19, EA 22), which Amenophis III. are completed (EA 23). Amenhotep apparently paid an extremely generous bride price.

EA 23 is the letter accompanying the shipment of the statue of Ishtar from Nineveh, which was already in Egypt at the time of Tušratta's father Suttarna. Amenhotep should always remember, however, that Ishtar is Tusratta's deity and not his. A reason for sending the statue is not given. If one considers the descriptions on the late Bentresch stele and Amenhotep's advanced age, the function as a salvation statue is obvious. The consecration gifts that Amenophis had sent to the northern Syrian deity Ichipe in Schimihe could also be interpreted in this sense.

In EA 24, Tušratta informs about the agreement on the border regulation of the cities of Charwuche and Maschrianne (?) And points out further controversial border regulations. In return for the generous dowry, he let Amenhotep III. to receive a few special gifts, but adds not exactly immodest demands on his part. It is the only letter in which Tušratta (for unknown reasons) does not write in Akkadian but in Hurrian .

EA 26 is the answer to a letter that Queen Teje , the wife of the late Amenhotep III, herself sends to Tušratta and in which she asks that Tušratta keep the friendship under her son Amenophis IV. In response, Tušratta complains that Amenhotep IV sent him inferior gifts, in contrast to Amenhotep III. In the other Mitanni letters, too, Tiy takes a central position (in contrast to the letters from Babylon, for example).

In the following letters, Tušratta assured Amenhotep IV of his friendship, but complained increasingly about inferior gifts that Amenhotep IV had given him. Amenhotep IV obviously does not keep the material promises made by his father Amenhotep III. before his death. In an angry letter (EA 28), Tušratta asks why he is holding onto the Mitannian messengers and what the reason is that they cannot enjoy mutual friendship. Amenhotep IV should ask Teje how he, Tušratta, had confessed to his father and should not listen to other whisperings. The angry attitude also corresponds to the rare fact that no presents were attached to the letter.

The situation worsens in EA 29. Amenophis IV still holds back the messengers and Tušratta feels offended by the inferior gifts. Tušratta's reaction may seem exaggerated, but if you consider the fundamentally friendly atmosphere in communication with Amenophis III, diplomatic resentments can be felt here. The correspondence breaks off at this point and it is not clear whether the Egyptians are trying to establish friendlier relations again.

Arzawa (EA 31-32)

The two Arzawa letters (EA 31 and EA 32) date, for paleographic and linguistic reasons, to the time between the Hittite kings Arnuwanda I and Suppiluliuma I. During this time of Hethic weakness, the empire in Western Anatolia was about to become the leading one Power to become in Anatolia. Therefore Egypt tried to ensure its loyalty and to prevent the Hittites from regaining their strength. The fact that the two letters were written in Hittite and not Akkadian, as usual, can be seen as a sign of Arzawa's previous isolation. In EA 31, Amenhotep asks for the daughter of Tarḫundaradu , king of Arzawa, in order to deepen relationships. In EA 32, the King of Arzawa readily agrees to the offer. The request to the Egyptian scribe to write clearly and always in Hittite shows "how insecure people were still on the diplomatic floor in Arzawa".

Alašija (EA 33-40)

Alašija (Alasia) was an important hub of trade between Egypt and Ugarit and to Anatolia and a kingdom fully integrated into the world of states of the Middle East, as the letters from that kingdom found in Egypt and Ugarit show. For a long time the location of Alašija was controversial. By petrographic some Amarna letters through tests of sound Yuval Goren , Israel Finkelstein and Nadav Na'aman the trapped foraminifera were identified and compared to clay tablets and fragments of known localities. This means that Alašija can be equated with southern Cyprus without a doubt .

It is not clear which language was spoken in Alašija in the Bronze Age. Some evidence suggests that it was originally Luwian-speaking and at some point came under Hittite influence, which is also indicated by the Cyprus inscriptions Šuppiluliuma II. According to Francis Breyer, the toponym Alašija could also be a reference to an originally Luwian coined Cyprus.

Trade and political issues are discussed in the Amarna letters. In EA 33 the king of Alašija confirms that he has received the message about the accession of the Egyptian king (presumably Amenophis IV). In EA 34, the king of Alašija refers to allegations that he did not send an ambassador to a festival of the Egyptian king. He apologizes and sends gifts for the festival of sacrifice (possibly in connection with the accession to the throne). Amenhotep IV apologizes for an overly greedy demand for copper (EA 35), which the king of Alašija was unable to meet due to an epidemic. A wife of the king even died at the "hand of Negral".

Alašija exports large quantities of copper and wood to Egypt, which are exchanged for silver and “sweet oil” (EA 35 to 37). The pharaoh reports that Luka, probably identical with residents of the Lukka countries (see also Lycians ), has molested the Egyptian area and he suspects that people from Alašija were also among them. The king of Alašija protests his innocence and reports that he is being harassed by Lukkäer himself. (EA 38) The king of Alašija demands with increasing emphasis that his messenger be returned (EA 37-38) and complains in EA 40 that there is no counterpart for To have received gifts. Here, too, he emphasizes that the messenger and his ship should not be held back. The Egyptian king has no claim to them.

Hittite Empire (EA 41-44)

A new population of Indo-European origin spread in central Anatolia towards the end of the Early Bronze Age . The native population, known as Hattier , was increasingly displaced by the newcomers, who over time split up into Hittites, Luwians and Palaers . In the early days the region was divided into principalities with branches of traders from Aššur . Ḫattušili I moved the residence of the Hittites to Ḫattuša (near today's Boğazkale ), which has apparently been abandoned since the ancient Assyrian period . This began the series of Hittite great kings ruling in Hattuša. The administration of the empire was feudal. Vassal kings submitted to the Hittite great king by oath.

The period in Hittite history known as the “middle” empire was marked by clashes with the states of Mitanni and Kizzuwatna . Mitanni, which extended its influence to northern Syria, was the main antagonist of the Hittite southeast expansion. At the end of the “middle” empire, the Hittite empire was in crisis. Despite some military successes of Tudhalija II with his son Šuppiluliuma I fighting at his side , some areas were able to break away from the Hittite Empire and it was reduced to central Anatolia. From this situation, Šuppiluliuma I was able to stand out as the founder of the New Kingdom or the Great Empire. He managed to recapture the Hittite territories in Asia Minor and a permanent expansion in northern Syria and north-western Upper Mesopotamia.

Unfortunately, only very few of the letters from the Hittite court to the Egyptian king have survived (EA 41-44) and some of them are only very fragmentary. The most important is EA 41, in which the Hittite great king Šuppiluliuma I addresses an Egyptian king who recently ascended to the throne, and he promises to maintain the same friendly relations as before. The name of the addressee is unclear. He is referred to as Ḫurij [a], obviously a typo for one of the Amarna kings Amenophis IV, Semenchkare or Tutankhamun. The interpretation of the name is closely related to the question of the chronology of Šuppiluliuma (especially with the dating of EA 75) and the identity of the deceased pharaoh in the Dahamunzu affair .

Šuppiluliuma I points out the Egyptian king's good relations with his father. They would never have refused each other's wishes. Suppiluliuma complains that the Pharaoh withheld gifts that his father had promised him.

The vassal correspondence

Letters from the Northern Vassals (Byblos and Amurru)

In the Egyptian areas south of Byblos , the city-states were close to one another and could be easily controlled. In the hinterland, north of Byblos to south of Ugarit, between the Orontes River and the Levantine coast, there was an area free of major city-states, about which little is known from the time before the Amarna Letters: Amurru .

The area was possibly under Thutmose III. nominally included in the Egyptian sovereignty, but the geographical, topographical and political situation probably made the administration of this area difficult. Traders and travelers have always run the risk of being attacked and robbed by lawless groups. They were easy prey for semi-nomads who stayed in the forests and mountains there and so could attack their victims without warning and disappear again without leaving any traces. This feature earned one of the most feared groups the name Habiru . Apparently the Habiru grew as more and more people and smaller groups joined them - voluntarily or through intimidation - and with the onset of Amarna correspondence, their leader Abdi-Aširta appeared as a real “warlord”. As the master of an area that is not organized as a city-state, Abdi-Aširta is regarded as the prototype of such a Habiru leader.

Geographically, the nominally Egyptian area bordered the Hittite Empire, which also endeavored to expand to the Middle East and subjugate the princes there. Amurru had to behave skillfully diplomatically between the fronts and therefore switched to the volatile policy, but was also able to use the situation for himself by playing off the great powers against each other.

Egypt had considerable strategic interest in this area: the coastal plain, irrigated by the Nahr el-Kebir, formed an important gateway to the inland, and the Homs pass, accessible from the Akkar plain, led to northern Syria and was thus an important route to Mesopotamia. The city of Sumur (possibly to be identified with Tell Kazel), which was located near the north bank of the Nahr el-Kebir, served as the administrative center of the area . The city was evidently the official seat of the "Commissioner" (rabisu) Paḫamnata, who was almost certainly Amenhotep III. had started. In Sumur there was a palace of the pharaoh (EA 62.15ff), the city was fortified (EA 81.49), had an Egyptian occupation (EA 62.23 and EA 67.10) and the governor had contingents of Egyptian troops (EA 131,31-38 and EA 132,34-41).

Main resistance to Abdi-Aširtas conquests came from Rib-Addi of Byblos. As a result of Abdi-Aširta's expansion, the pressure on Byblos increases, and so Rib-Addi sends calls for help to the Egyptian court with growing panic.

“[To] Amanappa, my father; the message Rib-hadda your son: I fell at the feet of my father. May the (divine) mistress of the city of Byblos give you honor before the king, your lord. Why do you stay still and not speak to the king, your lord, so that you can go out with regular troops and attack Amurru? If they hear that regular troops are leaving, they will leave their cities and desert. Don't you know Amurru (and) that they follow the strong? And now look: they don't like Abdi-širta. How does he treat her? They long for the regular troops to leave day and night, and I will do with them; all city princes long to undertake this against Abdi-Aširta; for he wrote to the men of the city of Ammija: “Kill your master and join the ˁapiru men!” Therefore the city princes say: “He will treat us the same way, and all countries will join the apiru men.” Now report on this matter before the king your lord; for you are father and lord to me and I have turned to you. You know the principles of my conduct (from the time) when you were in S] umur; for I am a faithful servant. And (now) speak to the king, [your] lord, so that an auxiliary force may be sent to me immediately. "

In EA 88 the cities of Ardata, Irqata, Ambia and Sigata are portrayed as threatened. Most of them fell into the hands of Abdi-Aširta from the letter EA 74, which Rib-Addi is now sending directly to the Egyptian king, probably Irqata as the first. At the instigation of Abdi-Aširta, the local ruler is killed and the population joins him as the new leader. By mentioning a campaign by the Hittite king, the events should be chronologically dated to the time of the first Syrian campaign of Šuppiluliuma.

Byblos Rib Addi is coming under increasing pressure. He narrowly escapes an assassination attempt (EA 82) and threatens Egypt to abandon Byblos itself and to join Abdi-Aširta (EA 82 and 83), just like Zimredda (the city prince of Sidon) and Japa-Hadda (the city prince of Beirut) ) have done.

Abdi-Aširta, on the other hand, repeatedly asserts his loyalty to the Egyptian king and asks for recognition as a vassal:

“[…] Look, I am a servant of the king and a dog of his house; and I protect the whole land of Amurru for the king my lord. I have repeatedly said to Paḫanate, the commissioner responsible for me: “Bring auxiliary troops to protect the king's lands!” Now all (vassal) kings of the king of the Hurrian troops strive to protect the lands of my control and control [of the Commissar] of the king to wrest from [my] lord. [But I] protect them. [...] "

After taking Irqata, Abdi-Aširta went to Sumur to save it from warriors from Šechlal. At least he justifies himself as if he had acted entirely in the interests of Egypt, which must have been preceded by a complaint from Egypt about this action. (EA 62) Apparently, Pahamnata was not in Sumur at this point in time, and the Egyptian occupation has also shrunk to four other officials.

More and more cities on the Lebanese Mediterranean coast fall into the hands of Abdi-Aširta and finally he reaches Byblos (EA 88). Abdi-Aširta's men also murdered the ruler of Surru (later Tire) and his wife - the latter was a sister of Rib-Addis. (EA 89) Finally, Japa-Hadda, the city prince of Beirut and former ally Abdi-Aširtas, also takes the position of Rib-Addi and writes about concern about the political situation in Amurru (EA 98).

At some point the hustle and bustle of Abdi-Aširta becomes too much for the Egyptians and the Egyptian king (probably Amenophis IV) sends troops against him. He is captured and dies for unknown reasons. (EA 101) Apparently the Egyptian general does not proceed with full determination and so Abdi-Aširta's sons can continue their father's work (EA 104). Quite the father, Abdi-Aširta successor Aziru also pursues an expansion policy and city after city falls back into the hands of Amurru, and he also justifies his actions that he is acting in the interests of Egypt and swears his allegiance to the Pharaoh (EA 156). One gets the impression that "the political developments in Syria are at least approved by the Egyptian side, and in some cases even promoted."

For the time being, Aziru successfully opposes the Pharaoh's request to come to an audience in Egypt (EA 156). In the end he did, however, as we learn from EA 161, in which Aziru retrospectively describes his stay in Egypt. During his stay in Egypt, his brothers kept him informed about political events in the Middle East. They report that the Hittites took cities in the Egyptian region of Amka. (EA 170)

Back in Amurru, too, Aziru reassures the pharaoh, who is concerned about his loyalty, but repeatedly postpones another audience in Egypt (EA 162, 166).

Ribaddi is overthrown by his brother and ultimately asks for refuge with Aziru. But this delivers the former prince of Byblos to the rulers of Sidon (EA 137), where Rib-Addi probably also finds his death. Aziru protested his loyalty to the Pharaoh to the end (EA 166), but changed camps in view of the ever advancing Hittites and concluded a contract with Šuppiluliuma I. An Akkadian and a Hittite version of the vassal treaty between Aziru and Šuppiluliuma I were found in the Hattuša archives (CTH 49).

Letters from the southern vassals

From the southern vassals (from the region of today's Palestine) there is no such extensive individual corpus as that of Rib-Addi or Abdi-Aširta and Aziru. Therefore, only limited political developments can be identified. Again, the main subject is the conflicts between the vassals. Similar to Aziru, Labaju of Shechem also tried to expand his territory. His main opponent was Biridija from Megiddo .

Apparently Labaju is punished for his unauthorized raids and campaigns. But the latter protests his innocence and his ignorance of these machinations: “The king has sent a message regarding (the extradition) of my son. I did not know that my son was traveling around with the ḫapiru men. ”(EA 254) The letter also shows that the vassals cooperated with the Habiru when it seemed convenient to them.

After the Egyptian king withdrew his regular troops from Megiddo (for unknown reasons) and after an epidemic broke out in Megiddo, Biridija wrote of Megiddo that his city was being besieged by Labayu of Shechem. ( EA 244 ) The Egyptians obviously demand the extradition of Labaius, but he dies before that happens. The Pharaoh blames Biridija for the death of Labaiu. The latter puts the blame on Surata von Akko, who killed him in an ambush. (EA 245) The sons of Labaius continued their father's work. (EA 250)

Suwardata of Gat complains to the king about Abdi-Hepa of Jerusalem that he, like Labaju, is expanding his territory on his own initiative: “Labaju, who used to take away our cities, is dead; and now ˁAbdi-Ḫeba is a second Labaju! [And] he takes away our cities. "(EA 280)

This Abdi-Hepa, in turn, protests his innocence and in turn complains about the sons of Labaju, who, together with Milkilu von Gezer and the Habiru gangs, are pursuing a violent policy of expansion. (EA 287) In EA 288, too, he asks urgently for military intervention against his enemies, as he is increasingly isolated: "I am in a situation like a ship on the high seas."

List of Amarna letters

| letter | Author, recipient | content | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| EA # 1 | Amenhotep III to King Kadashman-Enlil I of Babylon | ||

| EA # 2 | Babylonian King Kadashman-Enlil I to Amenophis III. | ||

| EA # 3 | Babylonian King Kadashman-Enlil to I. Amenophis III. | ||

| EA # 4 | Babylonian King Kadashman-Enlil I to Amenophis III. | ||

| EA # 5 | Amenhotep III to King Kadashman-Enlil I of Babylon | ||

| EA # 6 | Babylonian King Burna-Buriasch II to Amenhotep III. | ||

| EA # 7 | King Burna-Buriasch II of Babylon to Amenhotep IV. | ||

| EA # 8 | King Burna-Buriasch II of Babylon to Amenhotep IV. | ||

| EA # 9 | King Burna-Buriasch II of Babylon to Amenhotep IV. | ||

| EA # 10 | King Burna-Buriasch II of Babylon to Amenhotep IV. | Friendship between Egypt and Babylonia since the time of Kara-Indash | |

| EA # 11 | King Burna-Buriasch II of Babylon to Amenhotep IV. | ||

| EA # 12 | Princess ( ma-rat šarri ) to her master ( m bé-lí-ia ) | mentions the gods of Burna-Buriash | |

| EA # 13 | Babylon | ||

| EA # 14 | Amenhotep IV to King Burna-Buriasch II. | ||

| EA # 15 | Assyrian king Aššur-uballiṭ I to Amenhotep IV. | ||

| EA # 16 | Assyrian king Assur-uballit I to Amenhotep IV. | ||

| EA # 17 | King Tušratta of Mitanni to Amenophis III. | Tušratta sends booty from a campaign against Hatti to Amenophis III. (Nimmuriya) | |

| EA # 18 | King Tušratta of Mitanni to Amenophis III. | ||

| EA # 19 | King Tušratta of Mitanni to Amenophis III. | ||

| EA # 20 | King Tušratta of Mitanni to Amenophis III. | ||

| EA # 21 | King Tušratta of Mitanni to Amenophis III. | ||

| EA # 22 | King Tušratta of Mitanni to Amenophis III. | same tone as EA 24, 25 and 29 | |

| EA # 23 | King Tušratta of Mitanni to Amenophis III. | Marriage of Taduhepa , daughter of Tušratta with Amenophis III., Statue of Ishtar of Niniveh to Amenophis III. | |

| EA # 24 | King Tušratta of Mitanni to Amenophis III. | same tone as EA 22, 25, and 29 | |

| EA # 25 | King Tušratta of Mitanni to Amenhotep IV. | same tone as EA 22, 24, and 29 | |

| EA # 26 | King Tušratta of Mitanni to the widow Teje | ||

| EA # 27 | King Tušratta of Mitanni to Amenhotep IV. | ||

| EA # 28 | King Tušratta of Mitanni to Amenhotep IV. | ||

| EA # 29 | King Tušratta of Mitanni to Amenhotep IV. | same tone as EA 22, 24, 25 | |

| EA # 30 | The King of Mitanni to kings in Palestine | ||

| EA # 31 | Amenhotep III to King Tarhundaraba of Arzawa | ||

| EA # 32 | King Tarhundaraba of Arzawa to Amenophis III. | ||

| EA # 33 | The King of Alashiah to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 34 | The King of Alashiah to Pharaoh # 2 | Export of copper and wood | |

| EA # 35 | The King of Alashiah to Pharaoh # 3 | Notification of a plague; Problems with the copper delivery | |

| EA # 36 | The King of Alashiah to Pharaoh # 4 | ||

| EA # 37 | The King of Alashiah to Pharaoh # 5 | ||

| EA # 38 | The King of Alashiah to Pharaoh # 6 | ||

| EA # 39 | The King of Alashiah to Pharaoh # 7 | ||

| EA # 40 | Minister from Alashiah to an Egyptian minister | ||

| EA # 41 | Hittite king Šuppiluliuma I. to Huri [a] | ||

| EA # 42 | Hittite king to Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 43 | Hittite king to Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 44 | Hittite Prince Zi [k] ar to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 45 | King Ammistamru I of Ugarit to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 46 | King of Ugarit ... to King | ||

| EA # 47 | King of Ugarit ... to King | ||

| EA # 48 | Queen. . [h] epa from Ugarit to Pharaoh's wife | ||

| EA # 49 | Niqmaddu II , King of Ugarit to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 50 | Mrs. to her mistress B [i] ... | ||

| EA # 051 | Addu-nirari , king of Nuḫašše to the pharaoh | ||

| EA # 052 | Akizzi , King of Qatna to Amenhotep IV. # 1 | ||

| EA # 053 | Akizzi, King of Qatna to Amenhotep IV. # 2 | ||

| EA # 054 | Akizzi, King of Qatna to Amenhotep IV. # 3 | ||

| EA # 055 | Akizzi, King of Qatna to Amenhotep IV. # 4 | ||

| EA # 056 | Akizzi, King of Qatna to Amenhotep IV. # 5 | ||

| EA # 057 | …, King of Barga , to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 058 | Tehu-Teššup to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 059 | The people of Tunip to the Pharaoh | Messages to Pharaoh for 20 years | |

| EA # 060 | Abdi-Aširta , King of Amurru to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 061 | Abdi-Aširta, King of Amurru to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 062 | Abdi-Aširta, King of Amurru to Pahanate | ||

| EA # 063 | Abdi-Aširta, King of Amurru to Pharaoh # 3 | ||

| EA # 064 | Abdi-Aširta, King of Amurru to Pharaoh # 4 | ||

| EA # 065 | Abdi-Aširta, King of Amurru to Pharaoh # 5 | ||

| EA # 066 | --- to king | ||

| EA # 067 | --- to king | ||

| EA # 068 | Gubal king RibAddi to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 069 | RibAddi, king of Gubla to an Egyptian official | ||

| EA # 070 | Gubal king RibAddi to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 071 | RibAddi, king of Gubla to Haja | ||

| EA # 072 | Gubal king RibAddi to Pharaoh # 3 | ||

| EA # 073 | RibAddi, king of Gubla to Amanappa # 1 | ||

| EA # 074 | Gubal king RibAddi to Pharaoh # 4 | ||

| EA # 075 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 5 | ||

| EA # 076 | Gubal king RibAddi to Pharaoh # 6 | ||

| EA # 077 | RibAddi, king of Gubla to Amanappa # 2 | ||

| EA # 078 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 7 | ||

| EA # 079 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 8 | ||

| EA # 080 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 9 | ||

| EA # 081 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 10 | ||

| EA # 082 | RibAddi , king of Gubla to Amanappa # 3 | ||

| EA # 083 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 11 | ||

| EA # 084 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 12 | ||

| EA # 085 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 13 | ||

| EA # 086 | RibAddi, king of Gubla to Amanappa # 4 | ||

| EA # 087 | RibAddi, king of Gubla to Amanappa # 5 | ||

| EA # 088 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 14 | ||

| EA # 089 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 15 | ||

| EA # 090 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 16 | ||

| EA # 091 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 17 | ||

| EA # 092 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 18 | ||

| EA # 093 | RibAddi, king of Gubla to Amanappa # 6 | ||

| EA # 094 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 19 | ||

| EA # 095 | King RibAddi of Gubla to a great (general?) | ||

| EA # 096 | Great (general?) To RibAddi, king of Gubla | ||

| EA # 097 | Jappa'-Addi to Sumu-Haddi | ||

| EA # 098 | Jappa'-Addi to Janhamu | ||

| EA # 099 | Pharaoh to Ammijah's husband (?) | ||

| EA # 100 | The elders from Irqata to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 101 | Man from Gubla (Rib-Addi?) To an Egyptian official | ||

| EA # 102 | RibAddi, king of Gubla to Janhamu | ||

| EA # 103 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 20 | ||

| EA # 104 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 21 | ||

| EA # 105 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 22 | ||

| EA # 106 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 23 | ||

| EA # 107 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 24 | ||

| EA # 108 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 25 | ||

| EA # 109 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 26 | ||

| EA # 110 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 27 | ||

| EA # 111 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 28 | ||

| EA # 112 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 29 | ||

| EA # 113 | RibAddi, king of Gubla an Egyptian official | ||

| EA # 114 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 30 | ||

| EA # 115 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 31 | ||

| EA # 116 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 32 | ||

| EA # 117 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 33 | ||

| EA # 118 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 34 | ||

| EA # 119 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 35 | ||

| EA # 120 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 36 | ||

| EA # 121 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 37 | ||

| EA # 122 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 38 | ||

| EA # 123 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 39 | ||

| EA # 124 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 40 | ||

| EA # 125 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 41 | ||

| EA # 126 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 42 | ||

| EA # 127 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 43 | ||

| EA # 128 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 44 | ||

| EA # 129 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 45 | ||

| EA # 130 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 46 | ||

| EA # 131 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 47 | ||

| EA # 132 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 48 | ||

| EA # 133 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 49 | ||

| EA # 134 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 50 | ||

| EA # 135 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 51 | ||

| EA # 136 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 52 | ||

| EA # 137 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 53 | ||

| EA # 138 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 54 | ||

| EA # 139 | Ili-rapih and Gubla to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 140 | Ili-rapih and Gubla to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 141 | Ammunira , King of Beruta to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 142 | Ammunira, King of Beruta to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 143 | Ammunira, King of Beruta to Pharaoh # 3 | ||

| EA # 144 | King Zimrida of Sidon to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 145 | Zimrida to an officer | ||

| EA # 146 | Abi-milki , King of Tire to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 147 | Abi-milki, King of Tire to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 148 | Abi-milki, King of Tire to Pharaoh # 3 | ||

| EA # 149 | Abi-milki, King of Tire to Pharaoh # 4 | ||

| EA # 150 | Abi-milki, King of Tire to Pharaoh # 5 | ||

| EA # 151 | Abi-milki, King of Tire to Pharaoh # 6 | Dnwn mentioned ( Danuneans ) | |

| EA # 152 | Abi-milki, King of Tire to Pharaoh # 7 | ||

| EA # 153 | Abi-milki, King of Tire to Pharaoh # 8 | ||

| EA # 154 | Abi-milki, King of Tire to Pharaoh # 9 | ||

| EA # 155 | Abi-milki, King of Tire to Pharaoh # 10 | ||

| EA # 156 | Aziru , King of Amurru to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 157 | Aziru, King of Amurru to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 158 | Aziru, King of Amurru to Dudu # 1 | ||

| EA # 159 | Aziru, King of Amurru to Pharaoh # 3 | ||

| EA # 160 | Aziru, King of Amurru to Pharaoh # 4 | ||

| EA # 161 | Aziru, King of Amurru to Pharaoh # 5 | Sound corresponds to EA100 from Irqata | |

| EA # 162 | Pharaoh to Aziru, King of Amurru | ||

| EA # 163 | Pharaoh to ... | ||

| EA # 164 | Aziru, King of Amurru to Dudu # 2 | Sound corresponds to EA100 from Irqata | |

| EA # 165 | Aziru, King of Amurru to Pharaoh # 6 | ||

| EA # 166 | Aziru, King of Amurru to Hai | ||

| EA # 167 | Aziru, king of Amurru at [Dudu?] # 3 | ||

| EA # 168 | Aziru, King of Amurru to Pharaoh # 7 | ||

| EA # 169 | Son of Aziru ( Ari-Teššup ?) To an Egyptian official | Sound corresponds to EA100 | |

| EA # 170 | Baʿaluja (brother of Aziru) and Bet-ili at Aziru in Egypt | Sound corresponds to EA100 | |

| EA # 171 | Aziru, King of Amurru to Pharaoh # 8 | Sound corresponds to EA100, cf. also EA157 | |

| EA # 172 | --- | ||

| EA # 173 | ... to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 174 | Bieri of Hašabu to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 175 | 'Ildajja of Hasi the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 176 | ... to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 177 | Jamiuta , King of Guddašuna to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 178 | Hibija to a great one | ||

| EA # 179 | ... to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 180 | ... to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 181 | ... to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 182 | Šuttarna , King of Mušiḫuna to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 183 | Šuttarna, King of Mušiḫuna to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 184 | Šuttarna, King of Mušiḫuna to Pharaoh # 3 | ||

| EA # 185 | Majarzana , King of Hasi to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 186 | Majarzana from Hasi to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 187 | Šatija from Enišasi to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 188 | ... to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 189 | Etakkama from Kadeš to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 190 | Pharaoh to Etakkama (?) From Kadeš | ||

| EA # 191 | Arsawuja , King of Ruhizza to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 192 | Arsawuja, King of Ruhizza to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 193 | Tiwati to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 194 | Birjawaza of Damascus to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 195 | Birjawaza of Damascus to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 196 | Birjawaza of Damascus to Pharaoh # 3 | ||

| EA # 197 | Birjawaza of Damascus to Pharaoh # 4 | ||

| EA # 198 | Arašša from Kumidi to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 199 | ... to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 200 | ... to the Pharaoh | Reports about Achlameans and Karduniaš | |

| EA # 201 | Artemanja from Ziribasani to King | ||

| EA # 202 | Amajase to king | ||

| EA # 203 | Abdi Milki from Saschimi | ||

| EA # 204 | Prince of Qanu to the king | ||

| EA # 205 | Prince of Gubbu to the King | ||

| EA # 206 | Prince of Naziba to the king | ||

| EA # 207 | Ipteh ... to King | ||

| EA # 208 | ... an Egyptian official or king | ||

| EA # 209 | Zisamimi to king | ||

| EA # 210 | Zisami [mi] to Amenhotep IV. | ||

| EA # 211 | Zitrijara to King # 1 | ||

| EA # 212 | Zitrijara to King # 2 | ||

| EA # 213 | Zitrijara to King # 3 | ||

| EA # 214 | ... to king | ||

| EA # 215 | Baiawa to King # 1 | ||

| EA # 216 | Baiawa to King # 2 | ||

| EA # 217 | A [h] ... to the king | ||

| EA # 218 | ... to king | ||

| EA # 219 | ... to king | ||

| EA # 220 | Nukurtuwa from (?) [Z] unu to king | ||

| EA # 221 | Wiktazu to King # 1 | ||

| EA # 222 | Pharaoh to Intaruda | ||

| EA # 222 | Wik [tazu] to King # 2 | ||

| EA # 223 | En [g] u [t] a ( Endaruta ?) To king | ||

| EA # 224 | Sum-Add [a] to King | ||

| EA # 225 | Sum-Adda from Samhuna to King | ||

| EA # 226 | Sipturi_ to king | ||

| EA # 227 | King of Hazor | ||

| EA # 228 | King Abdi-Tirsi of Hazor | ||

| EA # 229 | Abdi-na-… to the king | ||

| EA # 230 | Iama to king | ||

| EA # 231 | ... to king | ||

| EA # 232 | King Surata of Akko to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 233 | King Satatna of Akko to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 234 | King Satatna of Akko to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 235 | Zitatna / (Satatna) to king | ||

| EA # 236 | ... to king | ||

| EA # 237 | Bajadi to king | ||

| EA # 238 | Bajadi | ||

| EA # 239 | Baduzana | ||

| EA # 240 | ... to king | ||

| EA # 241 | Rusmania to King | ||

| EA # 242 | Biridija , King of Megiddo to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 243 | Biridija, King of Megiddo to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 244 | Biridija, king of Megiddo to Pharaoh # 3 | Announcement of an epidemic and siege of the city. | |

| EA # 245 | Biridija, King of Megiddo to Pharaoh # 4 | ||

| EA # 246 | Biridija, King of Megiddo to Pharaoh # 5 | ||

| EA # 247 | Biridija, King of Megiddo or Jasdata | ||

| EA # 248 | Yes [sd] ata to king | ||

| EA # 248 | Biridija, King of Megiddo to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 249 | Baluursag | The Baluursag complained that Milkilu treated his soldiers badly | |

| EA # 249 | Addu-Ur. Say to the king | ||

| EA # 250 | Addu-Ur. Say to the king | Complaint by Baluursag about Milkilu | |

| EA # 251 | ... an Egyptian official | ||

| EA # 252 | Labaja to king | ||

| EA # 253 | Labaja to king | ||

| EA # 254 | Labaja to king | Labayu complains about attacks by Milkilu | |

| EA # 255 | Mut-Balu or Mut-Bahlum to King | ||

| EA # 256 | Courage Baloo to Janhamu | ||

| EA # 257 | Balu-Mihir to King # 1 | ||

| EA # 258 | Balu-Mihir to King # 2 | ||

| EA # 259 | Balu-Mihir to King # 3 | ||

| EA # 260 | Balu-Mihir to King # 4 | ||

| EA # 261 | Dasru to King # 1 | ||

| EA # 262 | Dasru to King # 2 | ||

| EA # 263 | ... to lord | ||

| EA # 264 | Tagi, head of Gezer to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 265 | Tagi, head of Gezer to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 266 | Tagi, head of Gezer to Pharaoh # 3 | ||

| EA # 267 | Milkilu , Mayor of Gezer to Pharaoh # 1 | Milkilu confirms that he has carried out an order from the Egyptian king | |

| EA # 268 | Milkilu, Mayor of Gezer to Pharaoh # 2 | Letter from Milkilu, content unclear. They are called gifts | |

| EA # 269 | Milkilu, Mayor of Gezer to Pharaoh # 3 | Milkilu asks for archers | |

| EA # 270 | Milkilu, Mayor of Gezer to Pharaoh # 4 | Milkilu complains about Yankhamu (an official of the Egyptian king) that he is blackmailing Milkilu | |

| EA # 271 | Milkilu, Mayor of Gezer to Pharaoh # 5 | Milkilu and Suwardatta are threatened by the Apiru | |

| EA # 272 | Sum ... to king | ||

| EA # 273 | Ba-Lat-Nese to King | Letter from Ninurman, who was the ruling ruler, noting that two of Milkilu's sons were nearly killed | |

| EA # 274 | Ba-Lat-Nese to King # 2 | ||

| EA # 275 | Iahazibada to King # 1 | ||

| EA # 276 | Iahazibada to King # 2 | ||

| EA # 277 | King Suwardatta of Qiltu to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 278 | King Suwardata of Qiltu to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 279 | King Suwardata of Qiltu to Pharaoh # 3 | ||

| EA # 280 | King Suwardata of Qiltu to Pharaoh # 3 | ||

| EA # 281 | King Suwardata of Qiltu to Pharaoh # 4 | ||

| EA # 282 | King Suwardata of Qiltu to Pharaoh # 5 | ||

| EA # 283 | King Suwardata of Qiltu to Pharaoh # 6 | ||

| EA # 284 | King Suwardata of Qiltu to Pharaoh # 7 | ||

| EA # 285 | Abdi-Hepat , King of Jerusalem to Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 286 | Abdi-Hepat, King of Jerusalem to Pharaoh | Abdi-Hepa complains about Milkilu (in reverse spelling Ilimilku) who is ruining the country | |

| EA # 287 | Abdi-Hepat, King of Jerusalem to Pharaoh | Abdi-Hepa complains about Milkilu who attacked the city of Qiltu | |

| EA # 288 | Abdi-Hepat, King of Jerusalem to Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 289 | Abdi-Hepat, King of Jerusalem to Pharaoh | Abi-Hepa complains about further conquests of Milkilu | |

| EA # 290 | Abdi-Hepat, King of Jerusalem to Pharaoh | Abi-Hepa complains about further conquests of Milkilu | |

| EA # 290 | King Suwardata from Qiltu to King | ||

| EA # 291 | … on … | ||

| EA # 292 | Addu-Dani, Mayor of Gezer to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 293 | Addu-Dani, Mayor of Gezer to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 294 | Addu-Dani, Mayor of Gezer to Pharaoh # 3 | ||

| EA # 295 | |||

| EA # 295 | Addu-Dani, Mayor of Gezer to Pharaoh # 4 | ||

| EA # 296 | King Iahtiri of Gaza | ||

| EA # 297 | Iapah [i] Mayor of Gezer to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 298 | Iapahi, Mayor of Gezer to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 299 | Iapahi, Mayor of Gezer to Pharaoh # 3 | ||

| EA # 300 | Iapahi, Mayor of Gezer to Pharaoh # 4 | ||

| EA # 301 | Subandu to King # 1 | ||

| EA # 302 | Subandu to King # 2 | ||

| EA # 303 | Subandu to King # 3 | ||

| EA # 304 | Subandu to King # 4 | ||

| EA # 305 | Subandu to King # 5 | ||

| EA # 306 | Subandu to King # 6 | ||

| EA # 307 | ... to king | ||

| EA # 308 | ... to king | ||

| EA # 309 | ... to king | ||

| EA # 310 | ... to king | ||

| EA # 311 | ... to king | ||

| EA # 312 | ... to king | ||

| EA # 313 | ... to king | ||

| EA # 314 | King Pu-Baʿlu of Jursa to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 315 | King Pu-Baʿlu of Jursa to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 316 | King Pu-Baʿlu of Jursa to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 317 | Dagantakala to King # 1 | ||

| EA # 318 | Dagantakala to King # 2 | ||

| EA # 319 | King Zurasar of A [h] tirumna to king | ||

| EA # 320 | King Widia of Ascalon to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 321 | King Widia of Ascalon to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 322 | King Widia of Ascalon to Pharaoh # 3 | ||

| EA # 323 | King Widia of Ascalon to Pharaoh # 4 | ||

| EA # 324 | King Widia of Ascalon to Pharaoh # 5 | ||

| EA # 325 | King Widia of Ascalon to Pharaoh # 6 | ||

| EA # 326 | King Widia of Ascalon to Pharaoh # 7 | ||

| EA # 327 | … the king | ||

| EA # 328 | Iabniilu, Mayor of Lachish to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 329 | King Zimridi of Lachish to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 330 | Sipti-Ba-Lu, Mayor of Lachish to Pharaoh # 1 | ||

| EA # 331 | Sipti-Ba-Lu, Mayor of Lachish to Pharaoh # 2 | ||

| EA # 332 | Sipti-Ba-Lu, Mayor of Lachish to Pharaoh # 3 | ||

| EA # 333 | Papi to an officer | ||

| EA # 334 | ... ie from Zuhra to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 335 | Abdi-Aširta, King of Amurru to Pharaoh # 6 | ||

| EA # 336 | Hiziri to King # 1 | ||

| EA # 337 | Hiziri to King # 2 | ||

| EA # 338 | Zi ... to king | ||

| EA # 339 | ... to king | ||

| EA # 340 | School text | ||

| EA # 341 | School text | ||

| EA # 342 | School text | ||

| EA # 343 | School text | ||

| EA # 344 | School text | ||

| EA # 345 | School text | ||

| EA # 346 | School text | ||

| EA # 347 | School text | ||

| EA # 348 | School text | ||

| EA # 349 | School text | ||

| EA # 350 | School text | ||

| EA # 351 | School text | ||

| EA # 352 | School text | ||

| EA # 354 | School text | ||

| EA # 355 | School text | ||

| EA # 356 | The myth of Adapa and the south wind | ||

| EA # 357 | Myth of Ereschkigal and Nergal | ||

| EA # 358 | Myth fragment | ||

| EA # 359 | Epic of the King of Battle, šar taměāri. | Linguistic Hittite influences | |

| EA # 360 | School text | ||

| EA # 361 | Part of EA # 56 | ||

| EA # 362 | Gubal king RibAddi to pharaoh # 55 | ||

| EA # 363 | Abdi-reša from Enišasi to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 364 | Ajjab from Aštartu (in Hauran ) to the Pharaoh | ||

| EA # 365 | Biridija, King of Megiddo to Pharaoh # 8 | ||

| EA # 366 | Šuwardata from Qiltu to Pharaoh # 9 | ||

| EA # 367 | Pharaoh to Endaruta of Akšapa | ||

| EA # 369 | Pharaoh to Milkilu von Gezer | Letter from the Egyptian king to Milkilu; the ruler sends presents and wishes in return very beautiful (female) cupbearers | |

| EA # 368 | School text | ||

| EA # 372 | School text | ||

| EA # 373 | School text | ||

| EA # 374 | School text | ||

| EA # 375 | Epic of the King of Battle, šar taměāri | Linguistic Hittite influences | |

| EA # 376 | School text | ||

| EA # 377 | School text? | ||

| EA # 379 | School text | ||

| EA # 381 | ... |

Raw material

The raw material of the tablets was examined in the research project Provenance Study of the Corpus of Cuneiform Tablets from Eretz-Israel , which is funded by the Israel Science Foundation . In this thin sections examined petrographic and neutron activation analysis conducted to determine the origin of the clay used and the panels. The research methods for this were published in 2002.

Research problems

The tablets were left behind in Amarna because they were probably no longer relevant at the time of the move. In more recent research, the main aim was to determine their exact origin based on the petrochemical composition of the clay tablets and thus to localize the respective authors, as this was not always possible with traditional methods.

One of the problems is the assessment of the relationship between the corresponding princes. The Pharaoh is pleaded for help on several tablets; the dramatically described events promise the loss of power and, in some cases, the life of the sender as a consequence of non-intervention by the Pharaoh. This led to the thesis that Akhenaten lived remote from the world in Amarna and that many provinces were lost under him. However, some Egyptologists, including Cyril Aldred , argue that these states should not be seen as direct parts of the Egyptian Empire, but merely as dependent states. Aldred thinks that the pharaohs deliberately strengthened some of these Asian petty rulers so that none of the petty empires could achieve a prominent position. The dramatic wording is the normal writing style of the rulers, and the pharaohs have withdrawn support from certain kingdoms in order to maintain the balance of powers.

literature

Editions

- Hugo Winckler (ed.): The clay tablet find from El Amarna (= Royal Museums in Berlin. Communications from the Oriental Collections. Volumes 1–3, ZDB -ID 275422-8 ). 2 volumes (in 3). Autographed by Ludwig Abel based on the originals . Spemann, Berlin 1889–1890.

- Carl Bezold , EA Wallis Budge : The Tell el-Amarna Tablets in the British Museum. British Museum et al., London 1892 ( online ).

- Otto Schroeder : The clay tablets of el-Amarna (= Near Eastern writing monuments of the Royal Museums in Berlin. Issue 11–12, ISSN 0138-449X ). 2 volumes. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1915 ( online ).

- Anson F. Rainey: The El-Amarna Correspondence. Volume 1. Brill, Leiden 2015.

Translations

- Jørgen Alexander Knudtzon (Ed.): The El-Amarna-Tafeln. With introduction and explanations. Notes and registers edited by Otto Weber and Erich Ebeling . Hinrichs, Leipzig 1915 (reprint. Zeller, Aalen 1964);

- Anson F. Rainey: El-Amarna Tablets 359-379 (= Old Orient and Old Testament. Volume 8, ISSN 0931-4296 ). Supplement to JA Knudtzon: The El Amarna tablets. Butzon & Bercker et al., Kevelaer et al. 1970.

- William L. Moran: Les Lettres d'el Amarna. Correspondence Diplomatique du Pharaon (= Littératures anciennes du Proche-Orient. Volume 13). Editions du Cerf, Paris 1987, ISBN 2-204-02645-X (In English: The Amarna Letters. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore MD 1992, ISBN 0-8018-4251-4 ).

- Mario Liverani (Ed.): Le lettere di el-Amarna. 2 volumes. Paideia, Brescia 1998-1999;

- Volume 1: Le lettere dei "Piccoli Re" (= Testi del Vicino Oriente antico. 2: Letterature mesopotamiche. Volume 3, 1). ISBN 88-394-0565-8 ;

- Volume 2: Le lettere dei “Grandi Re” (= Testi del Vicino Oriente antico. 2: Letterature mesopotamiche. Volume 3, 2). ISBN 88-394-0566-6 .

A selection of letters in German translation offers:

- Texts from the environment of the Old Testament . Volume 1: Legal and business documents. Delivery 5: Historical-chronological texts II. Gütersloher Verlags-Haus Mohn, Gütersloh 1985, ISBN 3-579-00064-0 , pp. 512-520.

- Texts from the environment of the Old Testament. New episode, Volume 3: Letters. Gütersloher Verlags-Haus Mohn, Gütersloh 2006, ISBN 3-579-05287-X , pp. 173–229.

Overview and individual questions

- Trevor Bryce : Letters of the Great Kings of the Ancient Near East. The Royal Correspondence of the Late Bronze Age. Routledge, London / New York 2003, ISBN 978-0-203-50498-7 .

- Edward Fay Campbell: The Chronology of the Amarna Letters. With Special Reference to the Hypothetical Coregency of Amenophis III and Akhenaten. The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore MD 1964.

- Raymond Cohen, Raymond Westbrook (Eds.): Amarna Diplomacy. The Beginnings of International Relations. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore MD et al. 2000, ISBN 0-8018-6199-3 .

- Yuval Goren, Israel Finkelstein , Nadav Naʾaman: Inscribed in Clay. Provenance Study of the Amarna Tablets and other Ancient Near Eastern Texts (= Tel Aviv University. Monograph Series of the Institute of Archeology. Volume 23). Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archeology, Tel Aviv 2004, ISBN 965-266-020-5 .

- Yuval Goren, Israel Finkelstein, Nadav Naʾaman: Petrographic Investigation of the Amarna Tablets. In: Near Eastern Archeology. Volume 65, No. 3, 2002, ISSN 1094-2076 , pp. 196-205, doi : 10.2307 / 3210884 .

- Yuval Goren, Israel Finkelstein, Nadav Naʾaman: The Expansion of the Kingdom of Amurru according to the Petrographic Investigation of the Amarna Tablets. In: Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. No. 329, 2003, ISSN 0003-097X , pp. 1-11, online .

- Yuval Goren, Israel Finkelstein, Nadav Naʾaman: The seat of three disputed Canaanite rulers according to petrographic investigation of the Amarna tablets. In: Tel Aviv. No. 2, 2002, ISSN 0334-4355 , pp. 221-237, doi : 10.1179 / tav.2002.2002.2.221 .

- Yuval Goren, Shlomo Bunimovitz, Israel Finkelstein, Nadav Naʾaman: The location of Alashiya: New evidence from petrographic investigation of Alashiyan tablets from el-Amarna and Ugarit. In: American Journal of Archeology. Volume 107, No. 2, 2003, ISSN 0002-9114 , pp. 233-255, doi : 10.3764 / aja.107.2.233 .

- Yuval Goren, Nadav Naʾaman, Hans Mommsen, Israel Finkelstein: Provenance study and re-evaluation of the cuneiform documents from the Egyptian residency at Tel Aphek. In: Egypt and Levant. No. 16, 2007, ISSN 1015-5104 , pp. 161-172, doi : 10.1553 / AE and L16s161 .

- Rolf Hachmann : The Egyptian administration in Syria during the Amarna period. In: Journal of the German Palestine Association. (ZDPAV). Volume 98, 1982, ISSN 2192-3124 , pp. 17-49.

- Jørgen Alexander Knudtzon: The two Arzawa letters: The oldest documents in the Indo-European language . JC Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung, Leipzig 1902 ( digitized version [accessed on November 5, 2017]).

- Cord Kühne: The chronology of the international correspondence from el-Amarna (= Old Orient and Old Testament. Volume 17). Neukirchener Verlag et al., Neukirchen-Vluyn et al. 1973, ISBN 3-7887-0376-8 (also: Berlin, Free University, dissertation, 1970).

- Mario Liverani: Amarna Letters. In: Kathryn A. Bard (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 133-135.

- Samuel AB Mercer, Frank Hudson Hallock (Eds.): The Tell el-Amarna Tablets. 2 volumes. Macmillan, Toronto 1939.

- Matthias Müller: Amarna letters. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (eds.): The scientific biblical dictionary on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff., Accessed on January 12, 2010.

- Juan-Pablo Vita: The Gezer Corpus of El-Amarna. Scope and writer. In: Journal of Assyriology. Volume 90, 2000, ISSN 0084-5299 , pp. 70-77, digital version (PDF; 1.2 MB) .

Relations between Egypt and the Middle East and Asia Minor

- Francis Breyer : Egypt and Anatolia. Political, cultural and linguistic contacts between the Nile Valley and Asia Minor in the 2nd millennium BC Chr. (= Austrian Academy of Sciences. Memoranda of the Gesamtakademie. Volume 63 = Contributions to the Chronology of the Eastern Mediterranean. Volume 25). Verlag Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 2010, ISBN 978-3-7001-6593-4 (also: Basel, University, dissertation, 2005).

- Wolfgang Helck : The relations of Egypt to the Middle East in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC Chr. (= Egyptological treatises. Volume 5). 2nd, improved edition. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1971, ISBN 3-447-01298-6 .

The Amarna period

- Marc Gabolde: D'Akhenaton à Toutânkhamon (= Collection de l'Institut d'Archeólogie et d'Histoire de l'Antiquite, ́ Universite ́Lumier̀e Lyon 2nd volume 3). Université Lumière-Lyon 2 - Institut d'archéologie et d'histoire de l'Antiquité et al., Lyon et al. 1998, ISBN 2-911971-02-7 .

- Frederick J. Giles: The Amarna Age. Egypt (= The Australian Center for Egyptology, Sydney. Studies. Volume 6). Aris & Phillips, Wiltshire 2001, ISBN 0-85668-820-7 .

- Alfred Grimm , Sylvia Schoske (ed.): The secret of the golden coffin. Akhenaten and the end of the Amarna period (= writings from the Egyptian collection. (SAS). Volume 10). State Collection of Egyptian Art Munich, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-87490-722-8 .

- Rolf Krauss : The end of the Amarna era. Contributions to the history and chronology of the New Kingdom (= Hildesheim Egyptological contributions. Volume 7). Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 1978, ISBN 3-8067-8036-6 .

- WM Flinders Petrie : Tell el Amarna. Methuen, London 1894 ( online ).

- Hermann Alexander Schlögl : Akhenaten - Tutankhamun. Facts and texts. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1983, ISBN 3-447-02337-6 .

Web links

- Matthias Müller: Amarna letters. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (eds.): The scientific biblical lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff., Accessed on May 26, 2012.

- Electronic version of the Amarna letters , Akkadian in English transliteration.

- Amarna letters ( Memento from July 17, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) in the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin

- EA Wallis Budge: discovery of the Amarna letters (English)

- mineralogy and origin (English)

- Selection of letters (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ See also Jörgen A. Knudtzon: Die El-Amarna-Tafeln. With introduction and explanations. Volume 1: The texts. Leipzig 1915, p. 4ff .; EA Wallis Budge: A History of Egypt from the End of the Neolithic Period to the Death of Cleopatra VII, BC 30: Egypt and her Asiatic Empire. 1902, p. 185; EA Wallis Budge: On Cuneiform Despatches from Tushratta, King of Mitanni, Burraburiyasch, the Son of Kuri-Galzu, and the King of Alashiya, to Amenophis III, King of Egypt, and on the Cuneiform Tablets from Tell el-Amarna. In: Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archeology. (PSBA) 10, 1887/8, p. 540; William M. Flinders Petrie: Syria and Egypt from the Tell el Amarna letters. London 1898, pp. 1f.

- ↑ Jörgen A. Knudtzon: The El Amarna tables. With introduction and explanations. Volume 1: The texts. Leipzig 1915, p. 4ff.

- ^ WM Flinders Petrie: Tell el Amarna. London 1894, p. 1.

- ^ WM Flinders Petrie: Tell el Amarna. London 1894, p. 23; Jörgen A. Knudtzon: The El-Amarna-Tafeln. With introduction and explanations. Volume 1: The texts. Leipzig 1915, p. 9ff.

- ^ WM Flinders Petrie: Syria and Egypt from the Tell el Amarna Letters. London 1898, p. 1.

- ^ WM Flinders Petrie: Tell el Amarna. London 1894, p. 19f.

- ^ William L. Moran: The Amarna Letters. Baltimore 1992, p. XIV. Note 9.

- ^ William L. Moran: The Amarna Letters. Baltimore 1992, p. XV.

- ^ William L. Moran: The Amarna Letters. Baltimore 1992, p. XVf.

- ^ William L. Moran: The Amarna Letters. Baltimore 1992, p. XVI.

- ^ Cyril Aldred: Akhenaten. God and Pharaoh of Egypt (= New discoveries in archeology. ). Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1968, pp. 215f .; William L. Moran: The Amarna Letters. Baltimore 1992, pp. XVIII ff.

- ^ Cyril Aldred: Akhenaten. God and Pharaoh of Egypt. Bergisch Gladbach 1968, p. 216.

- ↑ Jörgen A. Knudtzon: The El Amarna tables. With introduction and explanations. Volume 1: The texts. Leipzig 1915.

- ^ William L. Moran: The Amarna Letters. Baltimore 1992.

- ↑ Nib-mua-ria (= Neb-maat-Re) for Amenhotep III. and Nap-huru-ria (= Nefer-cheper-Re) for Akhenaten.

- ↑ See v. a. Rolf Krauss: The end of the Amarna era. ... Hildesheim 1978.

- ↑ Erik Hornung: Investigations on the chronology and history of the New Kingdom (= Egyptological treatises. Vol. 11). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1964, p. 66 (also: dissertation, University of Münster).

- ^ William L. Moran: The Amarna Letters. Baltimore 1992, pp. XXXVII.

- ↑ a b Erik Hornung: Investigations into the chronology and history of the New Kingdom. Wiesbaden 1964, p. 66.

- ↑ Krauss: The end of the Amarna period. ... Hildesheim 1978, p. 50 f .; Erik Hornung: Studies on the chronology and history of the New Kingdom. Wiesbaden 1964, p. 92.

- ↑ Erik Hornung: Studies on the chronology and history of the New Kingdom. Wiesbaden 1964, p. 92.

- ↑ Krauss: The end of the Amarna period. ... Hildesheim 1978, p. 52f.

- ^ Edward Fay Campbell (Jr.): The Chronology of the Amarna Letters. With Special Reference to the Hypothetical Coregency of Amenophis III and Akhenaten. Baltimore 1964, p. 138.

- ↑ Erik Hornung: Studies on the chronology and history of the New Kingdom. Wiesbaden 1964, p. 65.

- ^ William L. Moran: The Amarna Letters. Baltimore 1992, pp. XXXV.

- ^ Raimond Cohen, Raymond Westbrook (Eds.): Amarna Diplomacy. The Beginnings of International Relations. Baltimore / London 2000.

- ^ Trevor Bryce : Letters of the Great Kings of the Ancient Near East. The Royal Correspondence of the Late Bronze Age. London 2003, p. 16f.

- ↑ Jörg Klinger: The Hittites. Munich 2007, p. 42.

- ^ William L. Moran: The Amarna Letters. Baltimore 1992, p. 8.

- ^ William L. Moran: The Amarna Letters. Baltimore 1992, p. 16.

- ↑ Daniel Schwemer: From the correspondence with Babylonia and Assyria. In: Texts from the environment of the Old Testament. (TUAT) , New Series (NF), Volume 3: Letters. 2006, p. 178.

- ↑ Daniel Schwemer: From the correspondence with Babylonia and Assyria. In: TUAT, NF 3 , p. 175.

- ^ Trevor Bryce: Letters of the Great Kings of the Ancient Near East. The Royal Correspondence of the Late Bronze Age. London 2003, p. 11ff .; Helmut Freydank: Contributions to Central Assyrian chronology and history. Berlin 1991. Albert Kirk Grayson: Assyrian Royal inscriptions. Wiesbaden 1972.

- ↑ Schwemer: From the correspondence with Babylonia and Assyria. In: TUAT NF 3 , p. 178f.

- ↑ Schwemer: From the correspondence with Babylonia and Assyria. In: TUAT NF 3 , pp. 179f.

- ^ Francis Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. Vienna 2010, p. 162.

- ↑ SAB Mercer: The Tell el-Amarna Tablets. Vol. I, Toronto 1939, p. 167; Cord Kühne: The chronology of the international correspondence from el-Amarna. Neukirchen-Vluyn 1973, p. 20, note 85.

- ^ Alan R. Schulman: Diplomatic Marriage in the Egyptian New Kingdom. In: Journal of Near Eastern Studies 38, 1979, p. 189 note 54, as well as note 33–35; Francis Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. Vienna 2010, p. 158.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: The relations of Egypt to the Middle East in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC Chr. Wiesbaden 1971, p. 168.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: Documents of the 18th Dynasty. Translations for issues 17-22. 1961, p. 234.

- ^ Kühne: Chronology of the international correspondence. P. 19, note 82 .; Francis Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. Vienna 2010, p. 164.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: The relations of Egypt to the Middle East in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC Chr. Wiesbaden 1971, p. 169f.

- ↑ Jörgen A. Knudtzon: The El Amarna tables. With introduction and explanations. Volume 2: Notes and Register , Leipzig 1915, pp. 1050ff.

- ↑ For a long time the letter was the most important source for the development of grammar and dictionary of the Hurrian language. Nevertheless, the text is not completely understandable and the damage to the board causes further difficulties. See Gernot Wilhelm: Tušratta's letter from Mittani to Amenophis III. in Hurrian language (EA 24). In: TUAT, NF 3 , p. 180ff; Hans-Peter Adler: The Akkadian of King TuSratta von Mitanni. (= Old Orient and Old Testament. (AOAT) Vol. 201). Butzon & Bercker, Kevelaer 1976 / Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 1976, ISBN 978-3-7887-0503-9 .

- ^ William L. Moran: The Amarna Letters. Baltimore 1992, p. 102 Note 1

- ^ William L. Moran: The Amarna Letters. Baltimore 1992, p. 102, note 2.

- ^ Francis Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. Vienna 2010, p. 315.

- ^ Francis Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. Vienna 2010, p. 107.

- ^ Y. Goren, I. Finkelstein, N. Naʾaman: Inscribed in Clay. Provenance Study of the Amarna Tablets and other Ancient Near Eastern Texts. Tel Aviv 2004.

- ↑ Yuval Goren: The location of Alashiya. New Evidence from petrographic Investigations of Alashiyan Tablets from El-Amarna and Ugarit. In: American Journal of Archeology. No. 107, 2003, pp. 233-256.

- ^ Francis Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. Vienna 2010, p. 108.

- ↑ Semenchkare and Tutankhamun cannot be excluded. See William L. Moran: The Amarna Letters. Baltimore 1992, p. 104, note 1. According to Kühne, the Alasia correspondence spans about a decade in the reign of Amenhotep IV. See Hellbing: Alasia Problems. P. 47 note 47.

- ↑ Jörgen A. Knudtzon: The El Amarna tables. With introduction and explanations. Volume 2: Notes and Register , Leipzig 1915, pp. 1078f.

- ↑ Horst Klengel: History of the Hittite Empire. 1999, p. 18ff.

- ↑ Klengel: History of the Hittite Empire. P. 33ff.

- ↑ Klengel: History of the Hittite Empire. P. 85ff.

- ↑ Klengel: History of the Hittite Empire. P. 134ff.

- ^ Daniel Schwemmer: A letter from the Hittite great king (EA 41). In: Texts from the environment of the Old Testament. New episode. Volume 3: Letters. 2006, p. 190.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: The relations of Egypt to the Middle East in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC Chr.Wiesbaden 1971, p. 171.

- ↑ Thutmose III. landed in his 29th year of reign, on his 5th campaign to the Middle East, in the area of the mouth of the Nahr el-Kebir, where Sumur must have been, even if the city has not yet been named in this context. Rolf Hachmann: The Egyptian administration in Syria during the Amarna period. In: Journal of the German Palestine Association (ZDPAV) 98, 1982, p. 26.

- ^ Trevor Bryce: Letters of the Great Kings of the Ancient Near East. The Royal Correspondence of the Late Bronze Age. London 2003, pp. 145f.

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Helck: Relations between Egypt and the Middle East in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC Chr.Wiesbaden 1971, p. 172.

- ^ Francis Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. Vienna 2010, p. 166.

- ↑ Anson F. Rainey: Letters on the political developments in northern Lebanon at the time of Amenhotep III. and Amonophis' IV. In: Texts from the environment of the Old Testament (TUAT), New Series, Volume 3, Letters. Munich, 2006, p. 205.

- ^ Hachmann: The Egyptian administration in Syria. In: ZDPV 98 , p. 26

- ↑ Rainey: Letters on Political Developments in Northern Lebanon. In: TUAT NF 3 , p. 208.

- ↑ Rainey: Letters on Political Developments in Northern Lebanon. In: TUAT NF 3 , pp. 211f.

- ↑ Rainey: Letters on Political Developments in Northern Lebanon. In: TUAT NF 3 , p. 206.

- ↑ Rainey: Letters on Political Developments in Northern Lebanon. In: TUAT NF 3 , p. 220.

- ^ Francis Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. Vienna 2010, p. 168.

- ^ Anson F. Rainey: Letters from Palestine. In: Texts from the environment of the Old Testament. New episode, Volume 3: Letters. P. 195f.

- ^ Anson F. Rainey: Letters from Palestine. In: TUAT NF 3 , p. 197.

- ^ Anson F. Rainey: Letters from Palestine. In: TUAT NF 3 , p. 201.

- ^ Anson F. Rainey: Letters from Palestine. In: TUAT NF 3 , p. 204.

- ↑ a b c d A. Dobel, F. Asaro, HV Michel: Neutron activation analysis and the location of Waššukanni. In: Orientalia. 46, 1977, pp. 375-82.

- ↑ EA 35

- ↑ EA 244

- ^ A b Y. Goren, I. Finkelstein, N. Naʾaman: Inscribed in Clay. Provenance Study of the Amarna Tablets and other Ancient Near Eastern Texts. Tel Aviv 2004, pp. 76-87.

- ↑ Funding project: Grant No. 817 /02-25.0

- ^ A b Mineralogical and Chemical Study of the Amarna Tablets , in Near Eastern Archeology 6500 (2002): pp. 196-205

- ↑ Daniel Schwemer: From the correspondence with Babylonia and Assyria. In: TUAT, NF 3, page 173

- ↑ Erik Hornung: Studies on the chronology and history of the New Kingdom. Wiesbaden 1964, page 65