Aramaic languages

| Aramaic (ארמית / Arāmîṯ / ܐܪܡܝܐ / Ārāmāyâ ) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

|

|

| speaker | approx. 550,000 to 850,000 (native speakers of New Aramaic languages ) | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

arc |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

arc |

|

The Aramaic languages form a genetic sub-unit of the Semitic languages , which are a branch of Afro-Asian . Aramaic and Canaanite (including Hebrew and Phoenician , for example ) are the main branches of Northwest Semitic. The separation of Aramaic from Canaanite took place during the first half of the 2nd millennium BC. Instead of. All Aramaic languages go back to Altaramaic, which has been documented since the beginning of the first millennium BC.

Over the centuries, the approximately seventeen modern Aramaic languages developed from the classical Aramaic languages. These have around 550,000 to 850,000 speakers, mostly of the Jewish , Christian or Mandaean , rarely Muslim faith.

The original distribution areas are Iraq , Iran , Israel , Lebanon , Palestine , Syria and Turkey , in the autonomous Kurdish region of Rojava in Syria it is one of the official languages. Through migration processes (flight, resettlement, emigration) speakers of Aramaic languages first found their way to Russia , more recently mainly to Western and Central Europe , North and South America and Australia .

The scientific investigation of this language group is carried out by the Aramaistics . Classical Western Aramaic was the mother tongue of Jesus of Nazareth .

Classification of the Aramaic languages

For the position of Aramaic within Semitic see the article Semitic languages .

Language levels and languages

Today, Aramaic is usually divided into the following language levels and languages:

-

Altaramaic

- early Altaramaic (up to around 700 BC; Sfire steles, etc.)

- late Altaramaic (around the 7th and 6th centuries BC; Hermopolis papyri)

-

Imperial Aramaic

- Achaemenid Imperial Aramaic (5th to 3rd century BC; Elephantine papyri, etc.)

-

Middle Aramaic (from around 200 BC)

- biblical Aramaic

- Nabatean

- Palmyrenian

- Hatran

- Jewish-Middle Aramaic (Galilean and Babylonian Targumim , parts of the Book of Daniel )

-

Classic Aramaic

-

west

- Jewish-Palestinian (varieties: Targumish, Talmud-Galilean)

- Samaritan

- Christian-Palestinian (Melkite)

-

Central

- classic Syriac (varieties: East Syrian = Nestorian, West Syrian = Jacobite)

-

east

- classic Mandean

- Jewish-Babylonian (Talmudic)

-

west

-

New Aramaic (estimated numbers in brackets of today's speakers according to Ethnologue )

-

west

-

New West Aramaic in Syria (around 15,000 speakers in total)

- Dialect of the predominantly Christian ( Greek-Catholic ) village of Maalula

- Muslim group (with strong Arab influences)

-

New West Aramaic in Syria (around 15,000 speakers in total)

-

east

New Aramaic languages (as minority languages) in the 19th – 20th centuries Century (Linguarium map of Lomonosov University Moscow )

New Aramaic languages (as minority languages) in the 19th – 20th centuries Century (Linguarium map of Lomonosov University Moscow )

Christian groups (shown with colored areas):

Green hatched: Turoyo

Light brown: Hertevin (North Bohtan)

Light purple: Senaya

Light blue: Koi-Sanjaq

Yellow: Chaldean

Darker blue: Central Hakkari (with West Hakkari and Sapna dialect)

Green: North -Hakkari

Darker brown: Urmia

Green highlighted areas: more compact northeast Aramaic settlements at the end of the 19th century.

Violet hatching (left above the box): Refugee settlements at the beginning of the 20th century of the Chabur Assyrians (mostly northern and central Hakkari)

Red Star (in upper left corner): Mlahso †

Jewish groups (reference with numbers):

1 Lishana Deni, 2 Judäo -Barzani / Lishanid Janan, 3 Lishanid Noshan, 4 Lishan Didan, 5 Hulaula with speaking villages

Villages bordered by dashed lines: with Jewish and Christian speakers. Western New Aramaic, Bohtan and New Mandaean are common outside of the map section.- Northwest (mostly Syrian Orthodox (Jacobite) , seldom Syrian Catholic Christians, some Kurdish second speakers)

- Turoyo (62,000)

- Mlahso †

-

Nordost (English: North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic , abbreviation NENA)

- Christian group (mostly Chaldean , Assyrian and Old Assyrian Christians)

- Assyrian-New Aramaic (Nestorian-New Aramaic; dialects: Urmia, North Hakkari and Central Hakkari - the latter sometimes still divided into Central and West Hakkari and in the Sapna dialect in the Dohuk Governorate / Northern Iraq) (232,300)

- Chaldean-New Aramaic (Kaldaya) (206,000)

- Hertevin (1,000)

- Bohtan (1,000)

- Koi Sanjaq Surat (800)

- Senaya (Sanandaj) (500)

- Jewish group (see also Kurdish Jews )

- Urmiyah (Lishan Didan) (4,450)

- Sanadaj-Kerend (Hulaula) (10,350)

- Zachu-Armadiyah (Lishana Deni) (7,500)

- Arbil-Koi-Sanjaq (Lishana Noshan) (2,200)

- Bijil (Lishanid Janan, Barzani) (almost †, 0–20 speakers)

- Christian group (mostly Chaldean , Assyrian and Old Assyrian Christians)

- Southeast (see also Mandaeans )

- New Mandaean (5,500)

- Northwest (mostly Syrian Orthodox (Jacobite) , seldom Syrian Catholic Christians, some Kurdish second speakers)

-

west

Problem of classification

The division of the New Aramaic is particularly controversial. It should be noted that the boundaries of the Chaldean and Assyrian languages do not exactly correspond to the boundaries of the Chaldean Church and Assyrian Church . There are also villages of one church with the other language. In the southern plains, many Chaldean, Assyrian, Jacobite , Maronite and other Christians as well as Jews, Muslims and Mandaeans have switched to everyday Arabic for centuries ( Arabic Christians , Arabic Jews, etc.), and to the north also to other languages such as Kurdish. The spoken New Aramaic was rather withdrawn in mountainous regions.

In the literature, there are sometimes other classifications of the New Aramaic language groups by region than in the list above, for example in the map above: South-East Aramaic (Senaya), South Aramaic (Koi-Sanjaq), South-West Aramaic (Chaldean), Central Aramaic (Central Hakkari) and North Aramaic (North Hakkari).

Development of the Aramaic languages

Altaramaic

The period of Altaramaic is from the eleventh to the early seventh century BC. The oldest known dialects of Aramaic date from the 10th or 9th century BC. These are the Sam'ali of Zincirli the dialect of the inscription of Tell Fekheriye, the dialects of the central Syrian region and the dialect of Tel Deir 'Alla. Sometimes Sam'ali is not rated as an Old Aramaic dialect. Altaramaic can be divided into four dialect groups.

Aramaic was already of great importance as an international trade and diplomatic language in Assyrian times. During this time, which was created from the altaramäischen dialects Reichsaramäische . Neo-Assyrian reliefs show, side by side, scribes who write on clay tablets with a stylus , presumably using the Akkadian language (in cuneiform ), and scribes with scrolls who compose Aramaic texts. Aramaic inscriptions of the 7th century BC Chr. , For example from Zincirli and Nerab known in northern Syria / Southeast Anatolia. An Aramaic inscription from Tappeh Qalayci near Bukan in western Iran shows how far north the language was already widespread in the 8th or 7th century. Further to the east, some Luristan bronzes still bear Aramaic inscriptions. They may date from the 8th century, but dating is difficult without stratifiable finds.

Imperial and Middle Aramaic

In the multilingual Persian Empire , Aramaic became one of the supraregional imperial languages under the Achaemenids (chancellery languages of the court and the administration of the Achaemenid great king), alongside Old Persian , Elamite and Babylonian , and the only one of the four imperial languages that was not carved with cuneiform in clay, but with Ink was written on papyrus or parchment . This particularly standardized and unified variant of Aramaic is therefore called Imperial Aramaic . While most of the papyri in Imperial Aramaic are weathered today (with the exception of the Elephantine papyri and a few other examples from the dry desert climate of Upper Egypt), inscriptions in Imperial Aramaic are widespread from the entire area of the Achaemenid Empire from Asia Minor and Egypt to the Indus and into the post-Amenid period. As the earliest widespread alphabet script with ink on papyrus in the north, east and south of the empire, the unified Imperial Aramaic script had a great influence on the formation of alphabet scripts in the Caucasus ( Georgian script , Armenian script, etc.), in Central Asia ( Pahlavi script , Sogdian script, etc.) , in India ( Brahmi script , Kharoshthi script, etc.) and on the Arabian Peninsula ( Nabataean script , from which the Arabic script emerged), whose early variants were based on the model of the Imperial Aramaic script and which were initially very similar (cf. . Genealogy of the alphabets derived from the proto-Sinaitic writing ). In addition to his role as one of the chancellery and the Reich languages developed Imperial Aramaic stronger than the other three languages kingdom also for common language ( " lingua franca ") in everyday life of the Achaemenid Empire.

The high reputation of Imperial Aramaic as an imperial language and its fame as a lingua franca probably accelerated the process in which Aramaic superseded and replaced older languages of the fertile crescent , particularly Hebrew , Phoenician and Babylonian . The phase of Imperial Aramaic in the 5th to 3rd centuries BC BC was also the most unified language level of Aramaic, especially in written language. In the following 2200 years, in the Middle and Classical Aramaic period, increasing dialect differences emerged, which developed so far apart in the New Aramaic period that in some cases they were barely understandable or incomprehensible to one another and are therefore classified as separate languages in linguistics.

Its importance is also reflected in the Tanakh , where some late text passages are written in Aramaic. The Middle Aramaic passages of the books Daniel and Ezra are not kept in the same dialect, which is why biblical Aramaic (formerly also known as Chaldean) is criticized as a misnomer by Paul VM Flesher and Bruce D. Chilton. Holger Gzella, on the other hand, writes that the Aramaic-speaking parts of the Tanach offer "a largely uniform picture in terms of their linguistic form: the similarities between Daniel and Ezra outweigh the differences that exist". The biblical-Aramaic corpus is "close enough to the Imperial Aramaic to justify a treatment together with it", but differs clearly enough from it "not to be completely subsumed under it".

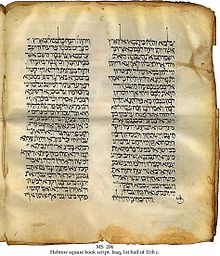

Since Hebrew was used in the second half of the 1st millennium BC, BC took over the Aramaic characters (" square script "), today both languages are written in the same script with 22 consonant characters within Judaism . Besides Hebrew, Aramaic is also felt to be the language of the Jewish tradition; thus the two Talmudim are written in Jewish-Aramaic dialects. Other dialects of Aramaic such as Palmyrenian , Nabataean , Syriac etc. developed their own script forms (see Nabataean script , Syriac alphabet ).

Aramaic inscriptions are known from Tayma in Arabia, dating from around 500 BC. To date. Numerous Aramaic inscriptions have also been found in the area of the Nabataeans , as well as on Sinai . From Parthian time many come Ostraka in Aramaic from Nisa in Turkmenistan . These are mainly business texts, orders from the palace kitchen.

In Palestine , Aramaic displaced Hebrew increasingly. At the time of Jesus , Aramaic was predominantly spoken there, and Aramaic phrases within the Greek New Testament , for example Abba , Golgotha and Maranatha , indicate that Aramaic was probably also the language of Jesus. Numerous texts that were found in Qumran are also written in Aramaic. At the turn of the ages, Aramaic was the common language of the Middle East alongside the Greek Koine .

Classic Aramaic

The later Targumim (Jewish Bible translations into Aramaic for synagogal use) and the Jerusalem Talmud (Palestinian Talmud), traceable from the second or third century, document the Jewish-Palestinian Aramaic (Galilean Aramaic). Like Christian-Palestinian and Samaritan, this Aramaic belongs to the Western Aramaic branch of the language.

Next to it is Eastern Aramaic, which is documented in the following language forms:

- Syriac, which is one of the best-documented forms of Aramaic, examples are the Peshitta (Christian-Aramaic translation of the Bible) and writings of the Syrian Church Fathers

- Jewish-Babylonian (the language of the Gemara in the Babylonian Talmud , geonic literature and numerous magic bowls )

- Mandaean

A feature of the eastern branch is, for example, the prefix of the 3rd person masculine (singular and plural), l- or n- instead of y- . In Mandaean and Syriac it is exclusively n- , in Judeo-Babylonian both variants alternate . In Jewish-Palestinian Aramaic, on the other hand, n- instead of y- only occurs in the plural masculine, in the singular the older y- has been retained.

Medieval and New Aramaic

With the spread of Islam , Aramaic was increasingly supplanted by Arabic and other languages (Persian, Kurdish, Turkish, Azerbaijani).

Within Judaism , Aramaic continued to be used in learned circles, including for works such as the Zohar . Benjamin von Tudela , who toured Kurdistan in the mid-12th century, reported that the Jews living there spoke Aramaic. From the end of the Geonim period to the “rediscovery” of spoken Aramaic by Europeans who traveled to Kurdistan in the 17th century, there is little evidence.

While spoken Aramaic has been pushed back more and more since the Middle Ages, especially in western and southern areas, Aramaic forms of language remained the sacred language and the written language for a long time in Syrian Christianity (see also Aramaic diglossia ). Over time, Aramaic also became rarer as a written language. It was later placed alongside Arabic as a sacred language in some western churches.

The persecution of the Christian Suroye / Suraye (also known as Assyrians , Arameans or Chaldeans ) and the demographic thinning of the Aramaic language islands in the Ottoman Empire through emigration, partly through flight or for political reasons, partly for economic reasons, began as early as the 19th century. Aramaic-speaking Christians first emigrated to Russia, then to the present day also to western countries, Lebanon and Jordan. The idea of nationalist attacks was provided by the western concept of the homogeneous nation-state that was advancing as a result of colonialism. They finally escalated into the genocide of the Assyrians and Arameans and that of the Armenians , which mainly affected northern and eastern Aramaic islands, less so those in present-day Iraq. Around 1915, well over 100,000 Christian Assyrians / Arameans lived in Eastern Anatolia alone; today there are probably only a few thousand in all of Turkey. Individual return migrations after the end of the Kurdish conflict in Southeast Anatolia will depend on the stability and legal security in the region. Since 1997, the teaching of the Aramaic language in Turkey has been prohibited by official decree. Due to the unrest in Iraq and the civil war in Syria , v. a. the people of the southern Aramaic islands are threatened by the spread of IS .

Today's New Aramaic languages and dialects are mainly preserved in Kurdistan , i.e. in southeast Turkey , northern Iraq and northeast Syria ; Aramaic is also spoken by Jews and Assyrians in western Iran . In contrast to the Jews, some of whom were able to re-establish themselves in Israel, the majority of the Assyrians find it difficult to maintain their culture, history and language in the diaspora which is spread over many countries . One of these East American languages is Turoyo . However, as a result of the upheavals in Iraq and the repressive religious and minority policies in Turkey, the main settlement areas of the Assyrians (also known as Aramaeans or Chaldeans ), this estimate seems too high. The last enclave of spoken New West Aramaic are the Christian village of Maalula and two neighboring Muslim villages in the Anti- Lebanon Mountains on the Syrian side.

Almost all of the Jewish speakers of Aramaic emigrated to Israel . In Israel there are some settlements and neighborhoods in which Aramaic is still the colloquial language of Jewish groups from Kurdistan (Northern Iraq), according to Ethnologue some neighborhoods in the Tel Aviv and Jerusalem area (including near the Hebrew University ) and in Mewasseret Zion . Yeshiva students, however, are usually not taught any grammar or vocabulary, instead they usually only learn Aramaic by heart in the Talmudic context, which is why, according to an experiment in Cambridge, they cannot read the Talmud on their own.

In the south of Iraq and southwest of Iran there are still several thousand members of the Mandaean religious community who speak the New Mandean language. In Iran itself, the Encyclopædia Iranica estimates around 24,500 Assyrian and 30,000 Chaldean Christians and around 500 Mandaeans, although it is not clear how many still use Aramaic forms of language.

Apart from a few regions in the Middle East, the New Aramaic languages are probably spoken today mainly by people who live in the diaspora in Australia , the USA , Europe and the former Soviet Union . At least 100,000 Aramaic-speaking Christians are said to have emigrated from Iraq since the collapse of Saddam Hussein's regime and fled to Jordan, Western and Central Europe and America. Modern Aramaic is threatened with extinction, among other things due to the linguistic assimilation of families who emigrated from the Middle East as well as families who linguistically adapted to the surrounding area, the often lack of communication of the languages to their descendants and the Syrian civil war.

font

The original Aramaic script is a consonant script written from right to left . Vowels are indicated in some places by matres lectionis , i.e. letters that are sometimes not to be read as consonants, but as phonetically similar vowels. Vocalization systems have been developed for some scripts of Aramaic origin .

The square script , which has presumably been used by Jews in place of the ancient Hebrew script since the Babylonian exile , is not only used in Hebrew and Jewish-Aramaic texts, but also in general in Jewish languages . Texts in square script are occasionally vocalized according to the Tiberian or Tiberian system known from the Masoretic text , which prevailed over the Palestinian and Babylonian vocalization systems , but mostly this script is written without vowel marks. For Samaritan Aramaic, the Samaritan script based on the ancient Hebrew was used.

Other Aramaic scripts are the Nabataean (from which the Arabic emerged ), the Palmyrenian, the Hatran, the Edessenian (from which the Syrian alphabet emerged ) and the Mandaean script used until today . The Syrian italics , so the Syrian Christianity used further developments of the Syrian alphabet, exists in three different forms: the westsyrische Estrangela and Serto and a third, with the Assyrian Church of the East associated form, the East Syriac or Nestorian script. The form of a large number of consonants depends on their position (unconnected, beginning, middle or end of a word). There are two vocalization systems. The Syriac script is also used today for Christian Neo-Aramaic languages, which are not necessarily direct descendants of the Syrian language.

Aramaistics

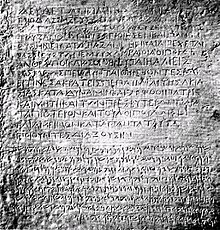

Aramaistics flourished after the Second World War . One of the most important finds of this time is the Letoon trilingue , a stele inscribed in Aramaic, Ancient Greek and Lycian languages, which contributed significantly to the understanding of Imperial Aramaic .

Aramaic in popular culture

Apart from speakers and scholars, Aramaic is often incorrectly assigned to the dead languages or is completely unknown to people outside these circles.

Many non-speakers came into contact with Aramaic through Mel Gibson's 2004 film The Passion of the Christ . The film was criticized , among other things, for the use of Latin instead of Greek as the local language and the negative portrayal of the Jews as well as the Aramaic spoken in the film and the falsifying subtitles. The mixture that makes up the Aramaic spoken in the film contains various grammatical errors.

In 2014, 32 private radio stations taught their listeners Aramaic in Switzerland. In the commercials, they were asked to use the sentence Schlomo, aydarbo? ("Hello, how are you?"). As part of the campaign, behind which “the majority of Swiss private radio stations and the national radio broker swiss radioworld AG” are, Aramaic was “simply declared the fifth national language”. This was done in collaboration with the Aramaic community in Switzerland.

literature

Cross-lingual

- Klaus Beyer: Introduction. In: Klaus Beyer: The Aramaic Texts from the Dead Sea. Aramaic introduction, text, translation, interpretation, grammar / dictionary, German-Aramaic word list, index. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1984, ISBN 3-525-53571-6 , pp. 20–153 (an outline of the history of language from antiquity to modern times, written by one of the leading Semitists of the present day).

- Stuart Creason: Aramaic. In: Roger D. Woodard (Ed.): The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 2004, ISBN 0-521-56256-2 , pp. 391-426.

- Joseph A. Fitzmyer, Stephen A. Kaufman (Eds.): An Aramaic Bibliography. Volume 1: Old, Official and Biblical Aramaic. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore MD u. a. 1992, ISBN 0-8018-4312-X .

- Holger Gzella: A Cultural History of Aramaic: From the Beginnings to the Advent of Islam (= Handbuch der Orientalistik ). Brill, 2015, ISBN 978-90-04-28509-5 , ISSN 0169-9423 (English).

- Holger Gzella, Margaretha L. Folmer (eds.): Aramaic in its Historical and Linguistic Setting (= Academy of Sciences and Literature, Mainz. Publications of the Oriental Commission. Vol. 50). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-447-05787-5 .

- Jürg Hutzli: Aramaic. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- Otto Jastrow : The Neo-Aramaic Languages. In: Robert Hetzron (Ed.): The Semitic Languages. Routledge, London a. a. 1997, ISBN 0-415-05767-1 .

- Stephen A. Kaufmann: Aramaic. In: Robert Hetzron (Ed.): The Semitic Languages. Routledge, London a. a. 1997, ISBN 0-415-05767-1 .

- Franz Rosenthal (Ed.): An Aramaic Handbook (= Porta linguarum Orientalium . NS Bd. 10, ZDB -ID 1161698-2 ). Two volumes (four parts in total). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1967.

Individual periods and languages

- Klaus Beyer: The Aramaic inscriptions from Assur, Hatra and the rest of Eastern Mesopotamia. (Dated 44 BC to 238 AD). Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1998, ISBN 3-525-53645-3 .

- Rainer Degen : Altaramaic grammar of the inscriptions of the 10th – 8th centuries Century BC Chr. (= Treatises for the customer of the Orient 38, 3, ISSN 0567-4980 ). Steiner, Wiesbaden 1969.

- Volker Hug: Altaramaic grammar of texts from the 7th and 6th centuries BC Chr. (= Heidelberg studies on the ancient Orient. Vol. 4). Heidelberger Orientverlag, Heidelberg 1993, ISBN 3-927552-03-8 (At the same time: Heidelberg, University, dissertation, 1990).

- Rudolf Macuch: Grammar of Samaritan Aramaic (= Studia Samaritana. Vol. 4). de Gruyter, Berlin a. a. 1982, ISBN 3-11-008376-0 .

- Christa Müller-Kessler: Grammar of Christian-Palestinian-Aramaic. Volume 1: Scripture, phonology, form theory (= texts and studies on oriental studies. Vol. 6, 1). G. Olms, Hildesheim u. a. 1991, ISBN 3-487-09479-7 (= at the same time: Berlin, Free University, dissertation, 1990).

- Stanislav Segert: Altaramaic grammar. 4th, unchanged. Edition. Verlag Enzyklopädie, Leipzig 1990, ISBN 3-324-00123-4 .

- Michael Waltisberg: Syntax of the Ṭuroyo (= Semitica Viva 55). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2016, ISBN 978-3-447-10731-0 .

Web links

- Achemenet - website maintained by Pierre Briant with information on Imperial Aramaic inscriptions from the Achaemenid period

- Foundation for the Preservation of the Aramaic Cultural Heritage

- Assyria TV - TV station broadcasting in New Eastern Aramaic

- An introductory course in Surayt Aramaic (Turoyo)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Sum of the speaker estimates by Ethnologue for the various Neo-Aramaic languages. (click)

- ↑ a b Cf. Yona Sabar : Mene Mene, Tekel uPharsin (Daniel 5:25) . Are the Days of Jewish and Christian Neo-Aramaic Dialects Numbered? In: Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies . tape 23 , no. 2 , 2009, p. 8th f . ( jaas.org [PDF; accessed August 25, 2015]).

- ↑ Sum of the estimates of native speakers of the new Aramaic language forms who are still fluent today. The total number of the more numerous speakers of classical Aramaic sacred languages, most of whom they have learned as a foreign language, is difficult due to the different language levels.

- ^ Paul Younan: Preservation and Advancement of the Aramaic Language in the Internet Age. Nineveh On Line, 2001, accessed on May 22, 2016 (English, Aramaic is understood here as a single language and is divided into 16 East Aramaic and one West Aramaic dialect.).

- ↑ Classification scheme for today's Aramaic languages in Glottolog from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology .

- ↑ Classification scheme for modern New Aramaic languages in Ethnologue .

- ^ Ernst Kausen : Afroasiatisch. 2005, accessed April 17, 2015 . ; Ernst Kausen: Language statistics of the continents. Number of languages and language families by parent continent. Retrieved April 17, 2015 .

- ↑ For the historical language levels of Aramaic see z. B. Efrem Yildiz: The Aramaic Language and its Classification . In: Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies . tape 14 , no. 1 , 2000, pp. 25–27 ( jaas.org [PDF; accessed April 23, 2015]).

- ↑ Classification scheme of modern New Aramaic languages . Some of the estimates refer to the Aramaist Hezy Mutzafi.

- ^ Estimate by Ethnologue .

- ↑ Estimate by Ethnologue , the difference to the "ethnic population" of 50,000 are probably Kurdish speakers.

- ↑ Information from Ethnologue , last native speaker died in 1998, an almost deaf woman also had knowledge, but hardly any language options.

- ^ Estimate by Ethnologue .

- ^ Estimate by Ethnologue .

- ^ Estimate by Ethnologue .

- ^ Estimate by Ethnologue .

- ^ Estimate by Ethnologue .

- ^ Estimate by Ethnologue .

- ^ Estimate by Ethnologue .

- ^ Estimate by Ethnologue .

- ^ Estimate by Ethnologue .

- ^ Estimate by Ethnologue .

- ^ Estimate by Ethnologue .

- ^ Estimate by Ethnologue .

- ^ A b Efrem Yildiz: The Aramaic Language and its Classification . In: Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies . tape 14 , no. 1 , 2000, pp. 25 ( jaas.org [PDF; accessed April 23, 2015]).

- ^ Paul VM Flesher, Bruce D. Chilton: The Targums: A Critical Introduction (= Studies in Aramaic Interpretation of Scripture ). Baylor University Press, Waco, Texas 2011, ISBN 978-90-04-21769-0 , pp. 269 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed April 1, 2015]).

- ^ Efrem Yildiz: The Aramaic Language and its Classification . In: Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies . tape 14 , no. 1 , 2000, pp. 27 f . ( jaas.org [PDF; accessed April 30, 2015]).

- ^ A b c Efrem Yildiz: The Aramaic Language and its Classification . In: Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies . tape 14 , no. 1 , 2000, pp. 28 ( jaas.org [PDF; accessed April 30, 2015]).

- ^ A b Efrem Yildiz: The Aramaic Language and its Classification . In: Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies . tape 14 , no. 1 , 2000, pp. 31 ( jaas.org [PDF; accessed April 30, 2015]).

- ^ A b c Efrem Yildiz: The Aramaic Language and its Classification . In: Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies . tape 14 , no. 1 , 2000, pp. 32 ( jaas.org [PDF; accessed April 30, 2015]).

- ^ Efrem Yildiz: The Aramaic Language and its Classification . In: Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies . tape 14 , no. 1 , 2000, pp. 29–32 ( jaas.org [PDF; accessed April 30, 2015]).

- ^ Paul VM Flesher, Bruce D. Chilton: The Targums: A Critical Introduction (= Studies in Aramaic Interpretation of Scripture ). Baylor University Press, Waco, Texas 2011, ISBN 978-90-04-21769-0 , pp. 267 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed April 1, 2015]).

- ↑ Michael Sokoloff : The Old Aramaic Inscription from Bukân: A revised Interpretation . In: Israel Exploration Journal . tape 49 , no. 1/2 , 1999, ISSN 0021-2059 , pp. 106 .

- ^ John CL Gibson: Textbook of Syriac Semitic Inscriptions . tape 2 : Aramaic Inscriptions Including Inscriptions in the Dialect of Zenjirli . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1975, pp. 57 .

- ^ A b c Richard Gottheil, Wilhelm Bacher: Aramaic Language Among the Jews. In: Isidore Singer (Ed.): Jewish Encyclopedia . Funk and Wagnalls, New York 1901-1906.

- ^ F. Rosenthal, JC Greenfield, Shaul Shaked: Aramaic in: Encyclopædia Iranica .

- ↑ Richard Nelson Frye ; GR Driver: Review of GR Driver's' Aramaic Documents of the Fifth Century BC in: Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 18 (1955) (3/4), p. 457.

- ^ A b Paul VM Flesher, Bruce D. Chilton: The Targums: A Critical Introduction (= Studies in Aramaic Interpretation of Scripture ). Baylor University Press, Waco, Texas 2011, ISBN 978-90-04-21769-0 , pp. 9 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed April 1, 2015] The authors use the dialect of the Book of Daniel and the Dead Sea Scrolls, some later texts such as Megillat Taanit , the Bar Kochba Letters and the older Targumim the term Jewish Literary Aramaic , the Aramaic of the Book of Esra is assigned to the Imperial Aramaic of the Persian Empire.).

- ↑ Holger Gzella: Tempus, Aspect and Modality in Imperial Aramaic (= Academy of Sciences and Literature: Mainz. Publications of the Oriental Commission . Volume 48 ). Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-447-05094-2 , p. 41, note 157 ( limited preview in Google book search [accessed April 8, 2015] The term Chaldean goes back to the Bible passage Daniel 2,4 ff., According to which the Chaldeans spoke Aramaic; this term was incorrectly derived from the the rest of the Jewish-Aramaic transferred. In the 15th and 16th centuries the term was mainly used in the succession of Johann Potken temporarily for Ethiopian.).

- ↑ Holger Gzella: Tempus, Aspect and Modality in Imperial Aramaic (= Academy of Sciences and Literature: Mainz. Publications of the Oriental Commission . Volume 48 ). Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-447-05094-2 , p. 42 f . ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed April 8, 2015]).

- ↑ Crawford Howell Toy, Richard Gottheil: Bible Translations. In: Isidore Singer (Ed.): Jewish Encyclopedia . Funk and Wagnalls, New York 1901-1906.

- ↑ a b c d e Jay Bushinsky: The passion of Aramaic-Kurdish Jews brought Aramaic to Israel. Ekurd Daily, April 15, 2005, accessed May 8, 2015 .

- ↑ a b c Stephen Andrew Missick: The Words of Jesus in the Original Aramaic: Discovering the Semitic Roots of Christianity . 2006, ISBN 1-60034-107-1 , pp. XI ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed April 1, 2015]).

- ^ Paul VM Flesher, Bruce D. Chilton: The Targums: A Critical Introduction (= Studies in Aramaic Interpretation of Scripture ). Baylor University Press, Waco, Texas 2011, ISBN 978-90-04-21769-0 , pp. 10 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed April 1, 2015]).

- ^ Efrem Yildiz: The Aramaic Language and its Classification . In: Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies . tape 14 , no. 1 , 2000, pp. 38 f . ( jaas.org [PDF; accessed April 30, 2015]).

- ^ Franz Rosenthal : Aramaic Studies During the Past Thirty Years . In: Journal of Near Eastern Studies . tape 37 , no. 2 . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago April 1978, pp. 82 , JSTOR : 545134 .

- ↑ On the Jewish-Babylonian Aramaic Michael Sokoloff: Jewish Babylonian Aramaic . In: Stefan Weninger (Ed.): The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook (= Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science ). tape 36 . Walter de Gruyter, 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-018613-0 , ISSN 1861-5090 , p. 665 .

- ↑ Bogdan Burtea: Mandaic . In: Stefan Weninger (Ed.): The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook (= Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science ). tape 36 . Walter de Gruyter, 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-018613-0 , ISSN 1861-5090 , p. 678 f .

- ↑ Helen Younansardaroud: Textbook Classical Syriac (= Semitica et Hamitosemitica 15), Aachen 2015, pp. 53–55.

- ↑ Michael Sokoloff: Jewish Babylonian Aramaic . In: Stefan Weninger (Ed.): The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook (= Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science ). tape 36 . Walter de Gruyter, 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-018613-0 , ISSN 1861-5090 , p. 615 .

- ↑ See map of Semitic languages in the Middle East (Russian) of the Linguarium project at Moscow's Lomonosov University. Light blue: Arabic; dark blue: Hebrew ( Ivrit ); red, green and yellow dots: minorities with neo-Aramaic languages.

- ^ Paul VM Flesher, Bruce D. Chilton: The Targums: A Critical Introduction (= Studies in Aramaic Interpretation of Scripture ). Baylor University Press, Waco, Texas 2011, ISBN 978-90-04-21769-0 , pp. 267 f . ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed April 1, 2015]).

- ^ Edward Lipiński : Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar (= Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta . Volume 80 ). 2nd Edition. Peeters, Leuven 2001, ISBN 90-429-0815-7 , pp. 73 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed August 18, 2015]).

- ^ Kurdish Jewish Community in Israel. Jerusalem Center for Jewish-Christian Relations, archived from the original on July 28, 2013 ; accessed on August 25, 2015 .

- ↑ Steven E. Fassberg: Judeo-Aramaic . In: Lily Kahn, Aaron D. Rubin (Eds.): Handbook of Jewish Languages (= Brill's Handbooks in Linguistics ). tape 2 . Brill, Leiden 2015, ISBN 978-90-04-21733-1 , pp. 73 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed December 29, 2015]).

- ↑ See brief overview text by the Aramaist Shabo Talay : The language and its position among Christians in the Orient. ( Memento from September 25, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) in the messages of the Mar Gabriel eV association 2002/03.

- ↑ see e.g. B. Tamar Gurdschiani: The Assyrians in Georgia. ( Memento from September 25, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) in the messages of Mar Gabriel eV 2002/03. There were other settlements in today's Armenia and Azerbaijan, some of which were also deported to the interior of Russia from near the border under Stalin .

- ↑ Turkey: Ten years prohibition to teach Aramaic. ISHR: unconditionally lift the teaching ban - ratify the UN pact without reservation. International Society for Human Rights , October 4, 2007, accessed September 23, 2015 .

- ↑ Turkey: Save the Aramaic Language! ISHR appeals for the cinema release of “Die Passion”. Jesus Christ spoke Aramaic - signature campaign against discrimination and illegality of the Aramaic language in Turkey. International Society for Human Rights, October 4, 2007, accessed September 23, 2015 .

- ↑ Human rights group calls for the rescue of the Aramaic language. Kath.net , March 17, 2004, accessed September 23, 2015 .

- ^ A b Ross Perlin: Is the Islamic State Exterminating the Language of Jesus? Foreign Policy , August 14, 2014, accessed August 25, 2015 .

- ^ A b c Efrem Yildiz: The Aramaic Language and its Classification . In: Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies . tape 14 , no. 1 , 2000, pp. 40 ( jaas.org [PDF; accessed April 23, 2015]).

- ^ Efrem Yildiz: The Aramaic Language and its Classification . In: Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies . tape 14 , no. 1 , 2000, pp. 25th f . ( jaas.org [PDF; accessed April 23, 2015]).

- ↑ See language area of Turoyo at Linguarium (Russian) southeast of Diyarbakır . Both shades: late 19th century, darker ocher: late 1960s.

- ↑ See map of Semitic languages in the Middle East (Russian) of the Linguarium project at Moscow's Lomonosov University. , red triangles for New West Aramaic.

- ↑ See the map of the historical Judaeo-Neo-Aramaic villages and language forms at Linguarium (English) (before emigration). On this map the names "Hulaula, Persian Kurdistani" and "Lishan Didan, Persian Azerbaijani" are drawn in the wrong direction by mistake. The former places where the Hulaula was spoken: Kerend and Sanandaj (see also alternative names above) and Saqiz, Suleimaniya (see following footnote), however, are marked at 5, which is Hulaula; the former language places Urmiyah (see alternative name) and Salmas, Mahabad (see following footnote) on the other hand at 4, which is Lishan Didan / Urmiyah (is also near Lake Urmiyah ).

- ↑ See ethnologue information on Hulaulá , Barzani-Jewish Aramaic , Lishana Deni , Lishán Didán and Lishanid Noshan .

- ↑ See map of Semitic languages in the Middle East (Russian) of the Linguarium project at Moscow's Lomonosov University. Yellow squares for New Mandean.

- ↑ Gernot Windfuhr: IRAN vii. NON-IRANIAN LANGUAGES (10). Aramaic. Encyclopædia Iranica , accessed September 23, 2015 .

- ↑ Jack Miles: The Art of The Passion . In: Timothy K. Beal, Tod Linafelt (Ed.): Mel Gibson's Bible: Religion, Popular Culture, and The Passion of the Christ . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago / London 2006, ISBN 0-226-03975-7 , pp. 11 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed April 1, 2015]).

- ^ Franz Rosenthal: Aramaic Studies During the Past Thirty Years . In: Journal of Near Eastern Studies . tape 37 , no. 2 . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago April 1978, pp. 89 , JSTOR : 545134 .

- ↑ Cf. Yona Sabar: Mene Mene, Tekel uPharsin (Daniel 5:25) . Are the Days of Jewish and Christian Neo-Aramaic Dialects Numbered? In: Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies . tape 23 , no. 2 , 2009, p. 6–17 ( jaas.org [PDF; accessed August 25, 2015]).

- ↑ Yona Sabar: Mene Mene, Tekel uPharsin (Daniel 5:25) . Are the Days of Jewish and Christian Neo-Aramaic Dialects Numbered? In: Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies . tape 23 , no. 2 , 2009, p. 10 ( jaas.org [PDF; accessed on August 27, 2015]).

- ↑ Yona Sabar: Mene Mene, Tekel uPharsin (Daniel 5:25) . Are the Days of Jewish and Christian Neo-Aramaic Dialects Numbered? In: Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies . tape 23 , no. 2 , 2009, p. 12 ( jaas.org [PDF; accessed on August 27, 2015]).

- ^ Peter T. Daniels : Scripts of Semitic Languages . In: Robert Hetzron (Ed.): The Semitic Languages . Routledge, Abingdon, Oxfordshire / New York, New York 2005, ISBN 0-415-05767-1 , pp. 22 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed August 18, 2015]).

- ^ Peter T. Daniels: Scripts of Semitic Languages . In: Robert Hetzron (Ed.): The Semitic Languages . Routledge, Abingdon, Oxfordshire / New York, New York 2005, ISBN 0-415-05767-1 , pp. 20 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed August 18, 2015]).

- ↑ Samaritan Aramaic. Ethnologue, accessed on October 8, 2015 .

- ^ Samaritan alphabet. Omniglot, accessed October 8, 2015 .

- ^ Klaus Beyer: The Aramaic Language: Its Distribution and Subdivisions . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1986, ISBN 3-525-53573-2 , pp. 50 ( limited preview in the Google book search [accessed on October 8, 2015] German: The Aramaic texts from the Dead Sea including the inscriptions from Palestine, Levi's testament from the Cairo Genisa, the scroll of fasting and the old Talmudic quotations . Göttingen 1984. Translated by John F. Healey).

- ^ John F. Healey: The Early Alphabet . In: JT Hooker (Ed.): Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet (= Reading the Past Series ). University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles 1990, ISBN 0-520-07431-9 , pp. 241 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed October 8, 2015]).

- ^ Peter T. Daniels: Scripts of Semitic Languages . In: Robert Hetzron (Ed.): The Semitic Languages . Routledge, Abingdon, Oxfordshire / New York, New York 2005, ISBN 0-415-05767-1 , pp. 20th f . ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed August 18, 2015]).

- ^ Peter T. Daniels: Scripts of Semitic Languages . In: Robert Hetzron (Ed.): The Semitic Languages . Routledge, Abingdon, Oxfordshire / New York, New York 2005, ISBN 0-415-05767-1 , pp. 21st f . ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed August 18, 2015]).

- ↑ John F. Healey: Syriac . In: Stefan Weninger (Ed.): The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook (= Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science ). tape 36 . Walter de Gruyter, 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-018613-0 , ISSN 1861-5090 , p. 639 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed August 18, 2015]).

- ^ Peter T. Daniels: Classical Syriac Phonology . In: Alan S. Kaye (Ed.): Phonologies of Asia and Africa . tape 1 . Eisenbrauns, 1997, ISBN 1-57506-017-5 , pp. 131 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed August 18, 2015]).

- ^ Edward Lipiński: Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar (= Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta . Volume 80 ). 2nd Edition. Peeters, Leuven 2001, ISBN 90-429-0815-7 , pp. 70 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed August 18, 2015]).

- ^ Peter T. Daniels: Classical Syriac Phonology . In: Alan S. Kaye (Ed.): Phonologies of Asia and Africa . tape 1 . Eisenbrauns, 1997, ISBN 1-57506-017-5 , pp. 128 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed August 18, 2015]).

- ^ Franz Rosenthal: Aramaic Studies During the Past Thirty Years . In: Journal of Near Eastern Studies . tape 37 , no. 2 . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago April 1978, pp. 81 , JSTOR : 545134 .

- ^ Franz Rosenthal: Aramaic Studies During the Past Thirty Years . In: Journal of Near Eastern Studies . tape 37 , no. 2 . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago April 1978, pp. 86 , JSTOR : 545134 .

- ^ Efrem Yildiz: The Aramaic Language and its Classification . In: Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies . tape 14 , no. 1 , 2000, pp. 39 ( jaas.org [PDF; accessed April 30, 2015]).

- ^ Diane M. Bazell, Laurence H. Kant: First-Century Christians in the Twenty-first Century: Does Evidence Matter? In: Warren Lewis, Hans Rollmann (eds.): Restoring the First-Century Church in the Twenty-first Century: Essays on the Stone-Campbell Restoration Movement . ISBN 0-226-03975-7 , pp. 357 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed April 1, 2015]).

- ↑ Jack Miles: The Art of The Passion . In: Timothy K. Beal, Tod Linafelt (Ed.): Mel Gibson's Bible: Religion, Popular Culture, and The Passion of the Christ . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago / London 2006, ISBN 0-226-03975-7 , pp. 12 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed April 1, 2015]).

- ↑ Jack Miles: The Art of The Passion . In: Timothy K. Beal, Tod Linafelt (Ed.): Mel Gibson's Bible: Religion, Popular Culture, and The Passion of the Christ . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago / London 2006, ISBN 0-226-03975-7 , pp. 13 f . ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed April 1, 2015]).

- ↑ Jack Miles: The Art of The Passion . In: Timothy K. Beal, Tod Linafelt (Ed.): Mel Gibson's Bible: Religion, Popular Culture, and The Passion of the Christ . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago / London 2006, ISBN 0-226-03975-7 , pp. 18th f . ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed April 1, 2015]).

- ^ Louis H. Feldman: Reflections on Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ . In: Zev Garber (Ed.): Mel Gibson's Passion: The Film, the Controversy, and Its Implications (= Shofar Supplements in Jewish Studies ). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago / London 2006, ISBN 0-226-03975-7 , pp. 94 f . ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed April 1, 2015]).

- ↑ Jack Miles: The Art of The Passion . In: Timothy K. Beal, Tod Linafelt (Ed.): Mel Gibson's Bible: Religion, Popular Culture, and The Passion of the Christ . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago / London 2006, ISBN 0-226-03975-7 , pp. 56 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed April 1, 2015]).

- ↑ Jessica Wonneberger: Radio makes Aramaic the fifth national language. swiss radioworld, May 22, 2014, archived from the original on May 18, 2015 ; accessed on September 27, 2014 (English).