Borbecksch Platt

| Borbecksch | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

Essen and Oberhausen

(the area of the former mayor's office Borbeck) ( Germany ) |

|

| speaker | Unknown | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | - | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

- |

|

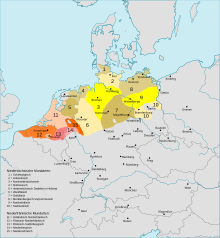

Borbecksch Platt (also called Borbecker Platt or Borbecksch for short ) is the Westphalian border and transition dialect spoken in the north-west of Essen and in the south-east of Oberhausen (the area of the former Borbeck mayor's office and its larger neighborhoods), which is located east of the unified plural line, is made up of elements of the Lower Saxon and Lower Franconian and is counted as South Westphalian . Despite its Lower Rhine-Lower Franconian elements, it is now counted as Lower Saxony.

classification

According to “Das Münster am Hellweg”, the historical area of the Imperial Monastery of Essen and thus also the language area of the Borbeck plateau belongs to West Munsterland , i.e. Lower Saxony. The West Munsterland originated from the mixture of the different ways of speaking of the Franks and the Saxons and shares many characteristics of the Lower Franconian, grammatically however it is close to the Westphalian / Saxon . The linguist Wrede called this dialect area in his explanatory text for the “German Language Atlas” as the “Dutch neighborhood” and compared it to Westphalian and its typically broken sounds such as , ue, ui .

The whole area between the course of the Issel , Dinkel and Ruhr was not only linguistically a cultural area before industrialization , also the right of inheritance, there was the right of inheritance , and the type of settlement, which was characterized by individual farms with two-tier houses , connected it.

history

9th to 13th centuries

After a few words in Latin texts, the regional language appeared for the first time shortly before the middle of the 9th century : Old Low German . In Latin texts one finds the expression lingua Saxonica ("Saxon language"). The few texts of this period that have survived to this day come from Essen , Münster and Freckenhorst and were made between 830 and 1050. Around the year 869 , one of the oldest finds from Essen or Borbeck from this period was made: It is a tax register or levy register in which Borbeck is mentioned as Borthbeki . From the middle of the 11th century to the beginning of the 13th century , Latin was used again for writing.

14th to 18th century

At the beginning of the 14th century , Old Saxon changed with a series of developments to what is now called Middle Low German . Within a century, supported by the Hanseatic League and the urban bourgeoisie, it became the leading written language in northern Central Europe and served as the lingua franca in the northern half of Europe . There is an influence of Middle Low German on the Scandinavian languages Danish , Norwegian and Swedish , which is characterized by numerous loanwords . There are Middle Low German documents from London in the west to Novgorod in the east and from Bergen in the north to Westphalia in the south. Middle Low German creates and leaves behind a considerable secular and ecclesiastical literature, place names, field names and, above all, many family names, extensive historical and legal literature as well as business prose in its area of application. Latin remains limited to the internal church and academic area of written language.

Despite the direction towards standardization, regional Middle Low German written languages can be broken down, which differ through linguistic variables. In Middle Low German, for example, there are four ê-sounds opposite two ô-sounds, which are simplified over time.

The area around Münster becomes the core area of a change that gives rise to the Westphalian plateau . The newly created Platt stands out above all for its many diphthongs . In the peripheral areas of this area of influence such as the Sauerland and the Lower Saxony areas of Westphalia, the development is weaker, in the center around Münster and in East Westphalia it is most pronounced. On this basis, the dialects in Westmünsterland as well as in South Westphalia and what is now the Dutch part of Westphalia are going through a further change: Many diphthongs (which were created from long vowels) are shortened by one element, so that short vowels are created (for example "essen" , im other Lower Saxon aät / eeten , in Westphalian iaten , in West Munsterland etten ). This development not only leads to the emergence of a different pronunciation, but also results in a different structure of the language. Since this simplification is carried out differently in Westphalia from landscape to landscape, the West Munsterland developed and, on the other hand, the South Westphalian, East Westphalian and Munsterland within the Westphalian.

But differences also develop within the West Munsterland. The farmers and the larger neighborhoods of the Borbeck quarter, an area that makes up about a quarter of the Essen monastery area and extends from the center of today's city of Oberhausen to the tenth border of the Reichsabbey Werden (today a district of Essen), linguistically belong to the western part of the Vestes Recklinghausen or Untervest and the dialect area that also includes the districts of Borken and Ahaus west of the Dinkel and the Dutch Achterhoek between Issel , Berkel and Dinkel . The unequal distance to other dialect areas such as the Lower Franconian language area and their influence on the local Platt create further differences. Borbeck's dialect gains peculiarities and develops into an independent local dialect: Borbecksch emerges.

Comparison of the South Westphalian Borbecksch with the four Westphalian dialect groups spoken in Germany :

| Standard German | Borbecksch | West Munsterland | South Westphalian | Münsterland | East Westphalian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard German | Hogedütsch | Hoogedüüts | |||

| House | Huus | Huus | Hius | Huus | Hius |

| week | Wake up | Wääke | Wiärke | Wiäken | |

| loaf | loaf | loaf | Brout | bride | bride |

| tree | boom | boom | pl. Gusts | tree | tree |

| to run | lopen | lopen | loup | loupe | loupe |

| foot | Faut | Foot | Faut | Foot | Fout |

| death | Dood | Dood | Doud | Daud | Daud |

| book | Bauk | Book | Bauk | Bok ( Pl.Boker ) | Bouk |

| stone | Steen | Steen | Stäin | Steen | Stäin |

| blood | Blue | Bloot | Blue | Bloot | Blout |

| Thief | Deiw | Deef | Daif | Daif | Däif |

| small | Kleen | small | klain | kleen, klain | small, small |

| dress | Kleed | Kleed | Kläid | Kleed | Klaid |

Due to the sparse population of Borbeck, formulations emerged that are only understood in the settlements in which they were created. For example, “De Berren leggen noch em Damm” is said in a Bedingrad settlement (the beds have not yet been made) , but this sentence is not understood elsewhere in Borbeck. Overall, however, the language follows the pattern of the place.

- Sovereign Song of the Former Peasants, 1500 , 1600 . (from Dellwig )

- Chew it on the arrogant,

- Bovesmann het kän Holt in For,

- Hüttmen es en Häunerdas,

- Halpmen sett dä cap ent what,

- Thick the back of the neck,

- Voss da can bake mares,

- Pülsmen dä third ent chopping board,

- Vonnemann sett, o wi rattles dät,

- Sandgathe takes a piece of bacon

- on skins Scheppmen domen an'n Bäck,

- Vieselmann es en brave man,

- Herskamp sett: ick weet nicks dovan,

- Krandiek es en Vuselstöcker,

- Rohmen es Uutsöpper.

Middle Low German remains independent of the local dialects together with Latin until the 17th century as a written language. However, it is characterized by a Westphalian substrate, but in general it follows the Lübeck standard. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Middle Low German was replaced by New High German, which was coined by Martin Luther . Gradually, it will be replaced by the standard German written language. Further reasons for the language change from Low German to High German are the downfall of the Hanseatic League and the emergence of an economic focus in southern Germany and letterpress printing .

19th century

After the end of the Reichsstift Essen in 1803, Borbeck became a municipality as a French-occupied area in 1808 . French vocabulary finds its way into the Borbeck dialect.

The reorganization of Europe by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 led to the Borbeck community becoming part of the Prussian Rhine Province . The independent Borbeck mayor's office is created . Despite the new affiliation, the dialect does not change.

With the advent of mining , Borbeck and the Ruhr area lost their village and agricultural character and were transformed into an industrial conurbation . In 1823 the Dinslaken and Essen districts, which were founded in 1816, were merged to form the Duisburg district, in which Borbeck and Altendorf form a mayor's office. By cabinet order of August 10, 1857, the Essen district together with Mayor Borbeck was removed from the Duisburg district and reorganized. Around 1840, several boreholes by various unions in the area of Borbeck in search of hard coal deposits worth building were found. You see many mines as incurred mine Wolfsbank , mine Neuwesel , mine Christian Levin , mine New Cologne and mine Amalie . In 1966 the last mine closes in the Borbeck area.

The towns in the Ruhr area are growing rapidly - albeit at a disproportionately high rate. In the first immigration phases many speakers come from low- and middle Frankish or Westphalian dialect areas in the following stages is a big influx from the four eastern provinces of the German Reich ( East Prussia , West Prussia , Silesia and Poznan ), which German , Polish or Masurian talk . Above all, immigration between 1850 and 1900 resulted in a seven-fold increase in the population in the Ruhr area. At this time, less than half of the residents in Essen or Dortmund and Duisburg were also born there.

The changes in tradition and community associated with immigration to the Ruhr area , such as the abandonment of customs and festivals and the change from village communities with informal communication structures to urban anonymity, serve as an indication of the significant changes that also have consequences on the traditional language system . The conditions that contributed to the expansion of the vocabulary and changes in the syntax of the source language during industrialization are direct influences on the language system. The increasing changes in all areas of life require a functioning administration. However, this presupposes that technical terms and neologisms are included. The restrictions on the use of the Low German dialects gradually mean that certain terms no longer find a desired expression in Low German. With the suppression of the Low German dialects in the Ruhr area, the high German lingua franca also spreads.

Another cause that leads to language changes is the massive relocation within cities and industrial areas. Few of the immigrants stay longer than a year in the respective place before they move on again to find better paid work elsewhere. The result is that learning local dialects is not worthwhile.

The Duisburg linguist Arend Mihm : “Since industrialization, the old dialects have no longer had a chance to remain the means of communication for the vast majority of the population. The small area related to the agricultural structure and the large distance to High German as the supra-regional language made the Low German varieties unsuitable for the large population movements that were necessary for the settlement of industry. "

The expansion of the school system in the 18th and 19th centuries, the general compulsory education and the emergence of inexpensive print products lead to a linguistic change. The teacher and local poet Hermann Hagedorn , who died in 1951, complains that no Low German was spoken during his school days: “Döt wo woll'n trurige tied by connoisseurs. On't wö all not necessary. With a few flat German Wöetken hääd'n sö ons that schools can make paradise. "

20th century until today

Standard German is increasingly becoming the language of communication between the rural population and immigrants in other languages, and the original local dialects have lost their social reputation for many residents of the Ruhr region in the decades after 1900. A new everyday language is developing, " Ruhrdeutsch ", which approaches the standard language, but is by no means to be equated with it. The respective local dialect colors each place in the Ruhr German. Until around 1914, Borbecksch was still spoken by the majority of Frintropers , Bedingraders , Dellwiger and Gerscheder , regardless of the Ruhr and High German . Even after 1914, the circle of speakers of the Borbeck dialect continued to shrink.

- Hermann Hagedorn - Heeme

- Hi'e it min Riek,

- So how ick klek!

- Where rondöm roe feet flames,

- Schachräe rushes on Kolwen stomps,

- Machines purr on Iser roars,

- Van Rollen on Stooten däre moans.

- On hoge öwer dät Gewemmel

- That's Hemmel.

- Do kloe on vuller prach,

- Bloo bi daage, schwatt bi Nach.

- Stands do aal da do'usend Joe

- Ewen splendid, ewen kloe.

- Bi da work, thou rough

- Blenkert hä mi friendly dew.

- Where ick goh

- On where ick stoh,

- A sunshine from the mountains to,

- En Wenterwend an Sommerprach,

- Bi Räegerusch on basin whispers

- Höe ick än heemlich, heemlich flispers ...

- Let me chisel! "Fit! Fit! Fit!"

- Ät lutt bold like Wee'en beeper,

- The happy joes sick the jonges cut ...

- I can grumble with the horn,

- Huh goes en't had mi so deip ...

- - Vader is singing!

- Mooder sings! -

- Heeme! Wat häw ick di leiw!

Today, the Borbeck dialects and the Low German dialects of the Ruhr area are no longer known to many Borbeckers - despite publications still appearing on Platt in the local newspaper Borbecker Nachrichten . The Kultur-Historische Verein Borbeck tries to cultivate the dialect with homeland afternoons in which native speakers recite poems and songs in Platt. The Mitten in Borbeck group also organizes activities to maintain the language. Among other things, visitors to the Borbeck Advent market were entertained with some pieces of Borbecksch. There was also a musical fair with a matching story. A memorial stone on Reuenberg, the Hagedornstein, commemorates the most famous representative of the dialect Hermann Hagedorn. Some street names such as Heeme (home) and the name of the carnival club Klein-Aff (Klein ab) are reminiscent of the Platt.

Phonetics and Phonology

Historical phonology

Like the other Low German dialects, the Borbecksch Platt did not go along with the second sound shift . The corresponding words in languages that also only participated in this sound shift to a small extent or not at all, such as Dutch , English , Danish , Swedish , Norwegian and Icelandic, are therefore similar to the words of Borbeck.

Consonants in Borbeck ↔ consonants in Standard German

d, dd → t:

- d anzen, Mi dd e ↔ t anzen, Mi tt e

t, tt → z:

- Lion t ant, Ha tt e ↔ lions z ahn, Her z

t, tt → s:

- Wa t he e tt s ↔ wa ss he e ss s

t, tt → tz:

- se tt s, dre tt ERIG ↔ se tz s, schmu tz ig

p → f:

- loo p , o s p büen ↔ lau f s, au f lift

p, pp → pf:

- P rumen, Ko pp ↔ Pf Laumen, co pf

k → ch:

- Kär k e, maa k s ↔ Kir ch e, ma ch s

w → b:

- Cried w disch, O w endskall ↔ cry b schematically, A b endsplausch

pronunciation

The linguistic landscape Essen - Enschede - Deventer , to which the Borbecksch belongs, is characterized by simple and broadly drawn E and O sounds. Together with the Lower Franconian in Mülheim , Dinslaken and Wesel , this has the simple vowels that are broken into short double sounds in Bochum , Gelsenkirchen and Recklinghausen (the historic county of Mark ) .

grammar

spelling, orthography

There is no uniform or binding spelling in Borbeckschen. The spelling is more or less individual. For example:

| opp Borbecksch | Standard German |

|---|---|

| Lüü or Lüh | People |

| Tiet or Tied | time |

| Threshing floor or Tänne | teeth |

morphology

Borbecksch is not a standardized language, grammatical rules have not been established. A comprehensive grammatical description of Borbeck's is therefore difficult.

Personal pronouns

| number | person | genus | Nominative | dative | accusative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1. | ick, ik | mi | mi | |

| 2. | you, you | di | di | ||

| 3. | Masculine | huh | |||

| Feminine | sö, se | ||||

| neuter | öt | ||||

| Plural | 1. | wi | ons | ||

| 2. | git, gitt | ||||

| 3. | sö, se |

Numerals

|

|

|

The prefix ge

In Borbeck, the prefix ge for characterizing the participle perfect, in contrast to dialects from West Munsterland such as Borks Platt ( Borken ) or Bokelts Platt ( Bocholt ), is completely present. The reason for this difference is probably the proximity to the Lower Franconian language area. In the Borbeck dialect, which borders directly on the Lower Franconian language area, people still say “Ick häw öm geseihen” or “Dä Moder het't gesagg” . In Bocholt (Bokelts Platt), which is further away from the border, the prefix in e- is already weakened (for example “He is upestaohn” or “He hew't nich edoan” ). In Borken, which is located in the middle of the Saxon language area, this already weakened e- has often disappeared. The general cause of this weakening or the disappearance of the prefix ge has not been clearly clarified.

Word formation

A common ending is "-ken / -sken". It serves to belittle the person mentioned respectively. the said thing. For example:

| opp Borbecksch | Standard German |

|---|---|

| Käezken | Little candle |

| Kendken | Child |

| Becksken | Brook |

This ending is also used in Ruhr German , a successor to the Plattes. For example:

| Ruhr German | Standard German |

|---|---|

| Bye | bye |

| Spässken | Jokes |

| Käffken | Coffee |

Verb forms in the plural

Borbeck lies on the unit plural line ("Westphalian Line") called the border between the Rhenish and Westphalian dialects. The Rhenish and Lower Rhine, like standard German, have two different forms in the present tense forms of the verbs in the plural. Westphalian is characterized by its unified plural in the present tense of the verb forms, which means that the first, second and third person are in the plural with the same verb form, which ends in -t in the indicative and -en in the subjunctive. In Borbeck there are both the Rhenish and the Westphalian forms.

Some words have different plural forms such as wi schluuten, gitt schlütt, sö schlotten (→ close) or wi send, gitt sid, sö send (→ sein) , with others there is only one form such as wi wett, gitt wett, sö wett (→ know) . There are both possibilities for many words: One could say wi mögd, gitt mögd, sö mögd as well as wi möggen, gitt mögd, sö may (→ like) .

- Plural forms in Borbeck ↔ common plural forms in Westphalian

- Example (do): wi maaken, gitt mackt, se mooken ↔ wi maket, gi maket, se maket

| ick (me) | you (you) | heh (he) | wi (we) | gitt (you) | sö (she) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| be | si | aton | it | send | sid | send |

| do | maak | mäcks | mäck | maaken | crap | mooken (also mackt) |

| to have | huh | hate | would have | häwwen | häwt | häwwen |

| come | come over | come piss | come | kömp, komp (also komen) | comp | komp (also komen) |

| to like | may, may | poss | may, may | mögd (also like) | poss | mögd (also like) |

| taste | taste | tastes | taste | taste | tastes good | taste |

| to cut | schni | sneeze | cut | snow | nice | snow |

| conclude | close | sleeps | sleep | close | sleep | Schlotten |

| have to | mott | moss | mott | mött | mött | mött (also mötten) |

| love | leiw | leiws | leiw | leiwen | leiwt | leiwen |

| lie | legg | leggs | lett | lay | lies | lay |

| give | gäw | giffs | giff | gäwwen | gäwt | gäwwen |

| go | goh | go | goes | gohen (also gont) | God | gohen (also gont) |

| to do | last | daus | daut | dauen (also daut) | daut | dauen (also daut) |

| knowledge | weet, bet | wees | weet | bet | bet | bet |

| to dance | danz | danz | danz | dance | danz | dance |

| sleep | schloop | Schlööps | Schlööp | closed | loops | closed |

| hold | holl | hell | hell | hollen (also hell) | get | hollen (also hell) |

| see | be | sweetie | seeks | strain | see | strain (also strain) |

| to run | loop | löpps | löpp | loop | lobs | loop |

| waiting | awake | grow | wakes | watch | watch | weeks (also weeks) |

| look | kiek | kieks | kicks | peck | kiekt | peck |

vocabulary

Personal designations

Like many other dialects, Borbecksche has a very rich vocabulary . For example, in addition to innumerable insults and harsh remarks that can be said, there are also a large number of words that characterize the relationships, behavior or properties of certain people or groups of people. Typical endings of many of these words are ~ kopp (~ head) (for example Klowerkopp, Quaterkopp, Kappeskopp, Zockskopp, Pröttelkopp) , ~ fott (~ buttern) (Klöngelfott, Wippfott, Schockelfott) and ~ bucksche (~ hose) (Kongelbucksche, Fuhlbucksche ) . Many insults are also related to animals such as dogs (honeys) (three-row honeys, pointed honeys, hat-eared honeys), pigs (Färkes) (Färkesbären, Färkesdäss) and goats (Hibben) (bange Hibbe) .

Another example of words that describe certain characteristics of people or groups of people is "girls". A big girl is called a Schleit , a little girl is called a Hümmelken or Hüppken . In a messy girl is called a Zubbelken : "Son Zubbelken mott were yet born" (not that a messy girl gives again) in a dirty girl from a Schmuddelken . Inventing further and new terms or words in general is easy and arises from the situation.

Little and little

Around 1885, people in Borbeck and all of today's north of Essen said mostly bettken or bittken (a bit) , while in the south of Essen they said bettschen. At least Hermann Hagedorn mainly used betschen in his poems and stories (for example "Wenterdagg" (Hatte on Heeme - Botterblaumen) ), but also related bettken ("Heißa hopp Kathrenneken" (also Hatte on Heeme - Botterblaumen) ).

| opp Borbecksch | Standard German |

|---|---|

| betschen | little |

| fitzken | little, very little |

| bettken | little, little |

| spit | a little, something |

Neighboring dialects

|

Osterfelder Platt

(South Westphalian) |

Bottropsch Platt

(South Westphalian) |

Altenessener Platt

(South Westphalian) |

| Meidericher Platt

( Kleverländisch ) |

|

Altenessener Platt

(South Westphalian) |

|

Mölmsch Platt

(Ostbergisch) |

probably Waddish Platt

(Ostbergisch) |

Essensch Platt

(South Westphalian) |

According to a map drawn by Helmut Hellberg in 1936 , which shows the dialect boundaries of the Low German language in the area between Langenberg in the south and Lippe in the north and Mülheim in the west and Recklinghausen in the east, Bottropsch Platt borders the Borbecksche in the north. The Emscher is considered the borderline, but there are hardly any differences between these two dialects.

| opp Borbecksch | opp Bottropsch | Standard German |

|---|---|---|

| en bettken deceptive | en bettken deceptive | a bit behind (stayed) |

| Et gitt no noise! | Et gitt no noise! | Have another sandwich! |

The Altenessener Platt borders in the northeast and east of Borbeck.

The Essensch Platt borders the Borbecksche in the southwest. It is the dialect of today's downtown Essen. Despite the close proximity to Borbeck and belonging to the same language area, the two dialects differ. In a newspaper article that appeared in the WAZ in 2007 , there is even astonishment at the immediate existence of Borbecksch and Essensch as two “very strongly” different dialects. One difference is, for example, the high German influence. Essen, which had been urbanized for a long time (today's Essen city center), was under a greater influence than Borbeck, which had remained rural for a long time. Johannes Pesch wrote in Borbecksch and Essensch.

The southern border is uncertain: According to the explanation of the size of the Borbeck language area in the booklet of the CD "Borbecksch Platt - Heeme, wat häw ick di leiw", the language area extends to the historic tenth limit of the Reichsabbey Werden . The local dialect is Waddish. According to Hellberg's map, it could also be that Frohnhausen , Holsterhausen and Rüttenscheid , which lie between Borbeck and Werden, form their own dialect area. Frohnhausen and Holsterhausen belonged to Borbeck's mayor until 1871.

The following comparison is based on the Platt Hermann Hagedorns (Borbecksch) and August Hahns (Waddisch) :

| opp Borbecksch | opp Waddish | Standard German |

|---|---|---|

| Wäe | Wäer | Weather |

| Müsche | Mötsch | Cap |

| Ped | Ped | horse |

| pläckebaasch | pleckebarwes | barefoot |

The Läppkes Mühlenbach separates the Borbeck dialect in the southwest from the Mölmsch Platt (Mülheim) . The vocabulary of the two dialects are sometimes very different. For example, teeth are called “Tenne” in Borbecksch, but “Teint” ( Dümpten ) or “Taun” in Mölmsch . For Mülheimers, who moved to Borbeck at the time, where Borbecksch was the most widely spoken language, there were great communication problems. There was even teasing about these language differences.

The following comparison is based on the Platt Hermann Hagedorns (Borbecksch) and the online Mölm dictionary of the city of Mülheim / Ruhr:

| opp Borbecksch | opp Mölmsch | Standard German |

|---|---|---|

| Düe | Düar | door |

| Wäe | Weer | Weather |

| Wiesche | Wiesche | Meadow |

| Era | Aed | earth |

| Ogenblick | Ougenbléck | moment |

| Schötte | Schotteldook | apron |

In the west, the places Alstaden and Styrum , which formerly belonged to the Broich rule, join. The local dialect is closely associated with Mölmschen due to the long, close relationship and is also part of Ostberg .

| opp Borbecksch | Alster Platt (Alstaden / Styrum) | Standard German |

|---|---|---|

| Be doe, min Jüngsken, what hesse doe said? | Süh do, min Jüngske, watt heste do saga? | Look there, my boy, what did you say? |

| Godden Dag ok, Mr. Wolf, joe, what are you going to do with everything, if huh! | Gun Dak ouk, Mr. Wolf, yo, watt see sunnen buck niet ahl, if süpp! | Good afternoon too, Mr. Wolf, yes, what does a buck like that say when he drinks! |

The Osterfelder Platt borders the Borbecksche in the northwest. As with Bottropsch Platt, the border line is the Emscher .

|

|

Examples

The Lord's Prayer"

|

|

|

|

Borbeck vocabulary

In addition to Low German , the French influence makes up the dialect's vocabulary. Some words are particularly similar to the Dutch language .

| opp Borbecksch Platt | Standard German | annotation |

|---|---|---|

| Trouble, booty | potato | Ärappel = derivation from Erdapfel , Är (a) ppelsdämmer = potato masher |

| Grayling | Axe | |

| Auwer | Embankment, slope | |

| Beä | beer | |

| Behei | Look, fuss | |

| Blötschkopp | Idiot / stupid person | |

| Botterramm or Dubbelten | Bread and butter | see. im Kölschen Butteramm , in Dutch boterham |

| Bollerbüx | Baby diaper | |

| Buxterhusen | non-existent place name | Widespread throughout the West Munsterland language area |

| Chapeau | cap | from the French adopted |

| Chaussée | Hauptstrasse (for example Frintroper Strasse) | taken from the French |

| Daätz | head | from French tête |

| thudding | bawl, sing | |

| dückes, dückers | often | |

| effelig, delicious | picky | |

| Emsche | Emscher | |

| ewkes, eevkes | just | it eevkes (just) |

| Fäesche | heel | |

| Flunsch | be offended | e.g. "draw a flunsch" (make an offended face) |

| Flons | dissolute, reckless or careless person | for example: You Flons van'e Käe |

| fottens, fots | immediately | |

| wet | blithely | "Holl di fuchte" ( keep yourself awake ) |

| Fuhlbucksche | Lazy | |

| Husband | Hole, hiding place | |

| Geitlenk | blackbird | |

| tingle | giggle | see. in Dutch giechelen |

| Hackepeter | Minced meat | |

| Would have | heart | "En'n Hatte väwaht" (enclosed in a heart) |

| Heeme | homeland | |

| Hosspes | Friend, lover, boss | |

| Huckbüen | Storeroom | |

| Hüülemuule | Person who always makes the mouth cry | |

| Iis | ice | |

| Isers | horseshoe | |

| hunt | to hunt | |

| Jankebaat | howling person | |

| Yeah | Joppe (jacket) | |

| Cubicle | small room | |

| Kajeere | Career, professional advancement | from French carrière |

| Kladderadatsch | Mess, all around, stuff | |

| Klömkes | sweets | |

| clunky | ragged | |

| Kneil | cinnamon | see. in Dutch kaneel |

| coning | To deceive | |

| Kisses | messy person | "Dät es son Küsselken" (This is such a sloppy person) |

| Rumors | everything that shines | a contraction of lantern and lamp |

| Live | lip | Lebbsche (thick lip) |

| borrowed | Suffer | "So muck mi all godd borrowed" (They all liked me) |

| funny | gloomy, dejected | |

| Pug | tea-cake | |

| mündkesmote | bite-sized | |

| Müsche | Cap | |

| Mostert | mustard | from French moutard , widespread on the Lower Rhine and in Cologne , Dutch : mosterd |

| mop | You mean mop (swear word) | see. in the Kölschen Möpp |

| Nodding | Quirks, quarrels | "... dückes sine nücken" (... often disputes) |

| nuseln | talk to yourself | |

| Grief | Proximity | |

| Ohme | uncle | see. in Dutch oom |

| Öösken | cute but clever kid | |

| opbüen | cancel | |

| Owendskall | Evening chat | Owend = evening; kallen = speak, chat |

| Parapluy | umbrella | from the French adopted |

| Pittermess | small kitchen knife | |

| pläckebaasch | barefoot | |

| Sperm weasels | growing children | |

| Pulling | wash / bathe | |

| Quark | complacent person | |

| Remmeltoote | total | |

| Remmeltroote | Litany (prayer) | |

| Ressong | reason | from French raison |

| roman on töm | all around | |

| Drooling | talk alot | |

| sloppy | unsightly, neglected | |

| Bye | mouth | |

| sönnertieds | now at this time | |

| Sooterdag | Saturday | |

| Kill | Coal Bucket | |

| deceitful | go back, stay behind | if someone is dumb, then he is "en bettken / betschen deceptive" |

| pavement | sidewalk | from the French adopted |

| Cloth | Laundry | "Dät Tüüch hänk op'e Liene" (the laundry hangs on the line) |

| Uchte | Christmas fair | "Goh gitt ok en'e Uchte?" (Do you also go to Christmas mass ?) |

| ullig | pathetic | |

| sickly | unpleasant | |

| vämutschen | devour | |

| Vänull | understanding | |

| väpräum | devour | |

| wat | what, something | "Wat van allerhand" (Something of everything) |

| Wämmse | Blows | |

| Wott | carrot | |

| fluting | work hard | |

| Zieselkes, Ziepel | Onions | |

| villus | variety | |

| Ruff | Soup |

literature

dictionary

Between 1960 and 1968 Willi Schlüter wrote a dialect dictionary, which Theo Saxe expanded in 2007. In connection with the publication of the CD “Borbecksch Platt - Heeme, wat häw ick di leiw” by the group “Mitten in Borbeck” in 2007, the local newspaper Borbecker Nachrichten started a series that consisted of this extended dictionary and accompanying drawings.

writer

Borbecksch:

- Hermann Hagedorn (born August 20, 1884 in Gerschede ; † March 7, 1951 in Fretter , Finnentrop municipality )

- Willi Schlueter (born August 8, 1899 - 1988)

- Willi Witte (* 1891 in Frintrop , † 1955)

- Hermann Witte (born November 27, 1889 in Frintrop; †)

- Josef Witte (* in Frintrop; †)

- Elisabeth Holte (* 1882 - 23 November 1958)

Borbecksch and Essensch:

- Johannes Pesch (born September 25, 1886 in Borbeck )

See also

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e The minster on Hellweg; 17th year; June 1964; Page 84ff

- ↑ Low German language

- ↑ Friedrich Engels : The Franconian dialect on zeno.org

- ↑ a b c Low German language

- ↑ a b plattdeutsch-niederdeutsch.net ( memento of the original from June 19, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ reese.linguist.de ( Memento of the original from September 3, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ kreis-borken.de (PDF; 3.9 MB)

- ^ Sauerland Platt

- ↑ a b ruhrgebietsssprache.de

- ^ A b High industrialization in Germany # Urbanization

- ↑ a b linse.uni-due.de (PDF; 1.8 MB)

- ↑ Georg Cornelissen: Between Köttelbecke and Ruhr . 2010

- ^ Record Hermann Hagedorn - Five poems in Essen-Dellwiger Platt

- ↑ at bvv-dellwig.de ( Memento of the original from July 18, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ dionysius.kja-essen.de ( Memento of the original from April 19, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Essen-Borbeck-Mitte

- ↑ Et giw more a bark - Naohloat up Platt and Hochdüts van Prof. Dr. Ludewig Walters . Page 142

- ↑ a b Yes, how do you speak? In: Borbecker Nachrichten , Volume 61 / No. 15, April 9, 2009

- ^ Hermann Hagedorn: Hatte on Heeme - Botterblaume; 2004; Page 55ff

- ↑ a b Booklet of the CD Borbecksch Platt - Heeme, wat häw ick di leiw

- ↑ Borbeck district newspaper: Platt is pioneering work . In: Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung , August 21, 2007

- ↑ Borbecksch Platt in the Low German Bibliography and Biography (PBuB)

- ↑ osterfeld-westfalen.de

- ↑ Phraseology of the West Munsterland dialect . In: Lexicon of the West Munsterland speeches , Volume 3, 2000, page 458