Danelag

The Danelag ( English Danelaw , - lage or - lagh , Middle English Denelage , Old English Dena lagu or Danish Danelagen , "Danish law") was an area in early medieval England that was conquered between 865 and 878 by the Danish Great Army , a Viking army . The Danelag was in northeast England and comprised parts of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Northumbria , which was defeated in 867, East Anglia , which was defeated in 869, and Merciawhich fell into the hands of the Danes in 874.

overview

The Danelag was settled by Scandinavians. How extensive this Scandinavian settlement of the Danelag actually was has not been conclusively clarified. The five fortified towns of Leicester , Lincoln , Nottingham , Stamford and Derby formed the military, administrative and economic centers of the Danelag. These five places are known as the five cities or five castles ("Five Boroughs"). The term Danelag for this area was not used until the middle of the 11th century to describe the areas of England that differed socially and legally from the Anglo-Saxon dominated. It is in contrast to Englaage , the English or Saxon law.

Only King Alfred of Wessex managed to defy the great army. In 878 he concluded a peace treaty with the Viking leader Guthrum , in which he recognized Danish rule in the northeast. In return, Guthrum was baptized and was able to rule over English territories as a Christian ruler. The conquest of the Danelag by the Kingdom of Wessex , which was finally completed in 954, led to the emergence of England. The culture, language, legal norms and organizational forms of the Scandinavian settlers provided important impulses for the development of English society.

Emergence

865 to 878: The Great Army

After various raids by Vikings in the first half of the 9th century on the British Isles, the attacks took on a new dimension from 850 onwards. While the raids were periodic up to then - the fleets looted in summer to return to Scandinavia in winter - that year a Viking army wintered for the first time in England on the island of Thanet off the Thames estuary . From raids carried out in a flash by small groups, the raids had turned into campaigns led by regular armies. The final turning point in this development marked the arrival of the Great Army in East Anglia in 865.

"[...] 7 þy ilcan geare cuom micel here on Angelcynnes lond, 7 wintersetl namon on Eastenglum, 7 þær obedience wurdon, 7 here him friþ wiþ namon."

"[...] And in the same year a great army came to England, and took winter quarters in East Anglia, and was provided with horses, and the inhabitants made peace with them."

Under its leaders, the brothers Ivar and Halvdan , the Viking army moved north over the Humber into the quarreling Northumbria in the same year and took its capital York on November 1st . The throne rivals Osberht and Ælle then united their armed forces, but were defeated and killed on March 21, 867 together with their armies by the Vikings. Northumbria with its capital York became a Scandinavian-dominated kingdom and the starting point for attacks on the rest of England. After the establishment of a tributary puppet king named Ecgberht I by the Vikings, the Great Army left Northumbria to invade Mercia . The Vikings spent the winter of 867/868 in a fortified camp in Nottingham , which they had conquered , besieged by the Mercian king Burgred , who, despite the military help of his brother-in-law King Æthelred of Wessex, could only get rid of the Vikings by paying a ransom. The Great Army withdrew to York the following year. In the year 869 the Danes continued their invasion with the occupation of East Anglia (winter quarters in Thetford ), in November 869 they defeated King Edmund of East Anglia at Hoxne and thus finally annexed his kingdom to their possessions. Edmund was venerated as a martyr soon after. In the following year the army under its leader Guthrum occupied the strategically located Reading on the Thames in order to conquer Wessex, and fought several battles with the West Saxons between 870 and 871 with varying results, for example at Englefield , at Reading itself, at Ashdown , Basing , and Merantūn (location unknown, maybe Marton ). A new fleet, which entered the Thames in 871, strengthened the Great Army at Reading. Alfred , who had taken over the reign of Wessex from his brother Æthelred, who died in 871, was unable to gain a decisive advantage despite nine other battles (including at Wilton ), and the exhausted opponents concluded a truce. The Vikings withdrew to London .

Between 871 and 874, the Great Army turned its focus on Mercia. Winter camps in London (871/872), Torksey (872/73) and finally Repton (873/874) in Derbyshire , seat and burial place of the mercian kings, formed the cornerstones of the army's route through Mercia. Extensive excavations made it possible to reconstruct the camp of the Great Army in Repton. Among other things, a mass grave with the bones of at least 249 members of the Viking army was discovered. After three years, Mercia had fallen. King Burgred preferred overseas exile in 874 (he died soon after in Rome) and the Vikings installed the shadow king Ceolwulf in his place. In the same year the army split into Repton. The leader of the army, Halvdan, moved to Northumbria with part of the army. After he had established safe borders there on the northern border river Tyne in battles against the Picts and the Britons of Strathclyde , he divided the country among his followers in the year 876. In just ten years East Anglia, Northumbria and Mercia had fallen into Danish hands, only Wessex still offered resistance.

The main army moved to Cambridge in 874 . From there, another attempt was made in 875 to conquer the last remaining Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex. Without encountering resistance, the army reached Wareham on the Channel coast, where it spent the following winter. In 876 it moved on to Exeter . After negotiations, the army withdrew to Gloucester in Mercia in 877 . The Vikings divided the country into an English West Mercia and a Danish East Mercia. They released the latter for settlement and thus reduced the strength of their army a second time. In 878 they invaded Wessex again, used Chippenham as a base and brought large parts of Wessex under their control. King Alfred withdrew to the impassable Somerset marshland , where he launched attacks on the Vikings from the fortified island of Athelney. In the spring of 878 Alfred and his now assembled army defeated the Vikings at Edington so severely that, after the ensuing siege of their headquarters in Chippenham, they consented to negotiations that resulted in the Treaty of Wedmore . The leader of the Vikings, Guthrum , was baptized with thirty of his followers, took hostages and later that year withdrew from Wessex to Cirencester , Mercia. In 879 the army finally moved to East Anglia to divide the country among themselves. In 880 Guthrum left England with some of his men to plunder the Carolingian Empire on the continent .

Attacks between 892 and 896

Wessex was quiet until 884. That year Guthrum landed at Rochester in Kent , where his army was reinforced by Vikings from East Anglia. King Alfred, who had had time to build up an effective defense in previous years, was able to repel the attack until 886 and also conquer London. The Wedmore treaty was renewed and a demarcation agreed: up the Thames, and then up the Lea , and along the Lea to its source, then in a straight line to Bedford , then up the Ouse to Watling Street .

Larger attacks did not take place again until 892, when the Great Army, which was formed on the continent in 879 and had since plundered Franconian areas on the Rhine , Meuse , Scheldt , Somme and Seine , sailed in two groups to England and camped in Kent (Milten Regis, Appledore). After the groups were united, the army moved in 893 to Buttington in the west of Mercia, in order to plunder Mercia and Wales from there . However, the Viking army was besieged by a Welsh-English army and evaded the ruins of the abandoned Roman fortress of Chester in north Mercia, where they received support from compatriots from the Danelag. At the same time, Exeter was attacked by another group of Vikings. After Wales was sacked the following year, the army withdrew from Chester to Mersea, Essex . Alfred successfully besieged a camp on an island in Lea in 894. Another advance of the Vikings in 895 to Bridgnorth on the Severn was unsuccessful, so that the army disbanded in 896. Parts settled in the Danelag. Those who did not own enough to buy land there moved to the Franconian Empire in order to gain wealth by looting further along the Seine.

Against new attacks and looting from the Danelag in 896 against the south coast of Wessex, on Wight and in Devonshire , Alfred also used ships that he had built according to his own plans. Due to their size - twice as big as the Danish, higher, wider and with sixty or more oars - they were ultimately not superior to the more agile ships of the Vikings at sea, so that the success of the English fleet remained changeable, especially since the Danes too more experienced sailors were.

Conquest of the Danelag by Wessex

When King Alfred of Wessex died in 899, he left a solid empire. The Burghal Hidage , a document recorded around 910, shows that he had at least thirty places fortified in Wessex. These included old Roman camps (such as Portchester ) and cities (such as Exeter or Winchester ), new cities (such as Wareham or Wallingford ) and prehistoric ramparts ( Pilton ). These fortified places were financed by hoof taxes and manned by farmers. Alfred divided the army into two halves, one of which was always under arms. Thanks to these prerequisites, his son and successor Edward the Elder (king from 899 to 924) was able to begin the conquest of the Danelag. After the death of his brother-in-law Æthelred, Eduard was given control of the Thames Valley, which served him as a starting point for his conquests. Together with his sister Æthelflæd, who continued to rule Mercia, he conquered the southeastern area of Mercias and East Anglia in the years up to 918, by gradually eliminating individual Viking groups. A Northumbrian attack was repulsed at the Battle of Tettenhall in 910. The Danelag's weakness following the British victory favored Edward's conquests. To secure the areas under his control, new burhs continued to be built . By 920 the area of the Five Cities had also been conquered. 919–920 the burhs of Thelwall, Manchester and Bakewell were finally created in the northern border area as the starting point for the conquest of the Kingdom of York . The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports on Edward the Elder for the year 920:

"[...] geces þa to fæder 7 to hlaforde Scotta cyning 7 eall Scotta þeod; 7 Rægnald, 7 Eadulfes suna, 7 ealle þa þe on Norþhymbrum bugeaþ, ægþer ge Englisce, ge Denisce, ge Norþmen, ge oþre; 7 eac Stræcledweala cyning, 7 ealle Stræcledwealas. "

“[…] The King of Scots and the Scottish people and Ragnvald and the sons of Eadwulf and all who live in Northumbria, both English and Danish, Northmen and others, and the King of Strathclyde and all of Streathclyde chose him as father and lord . "

As ruler over the whole of England, Eduard also exercised a kind of supremacy over the adjacent areas of his domain. Wessex was the only survivor of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms to prevail against the Danelag. Through the unification of the various territories, the Kingdom of England emerged in the following years, and Edward the Elder can thus - without diminishing the achievements of Alfred the Great - be considered the first all-English king.

The Danish-dominated Kingdom of York was involved in a defensive battle against Norwegian Vikings from Dublin at the beginning of the 10th century and was therefore unable to counter the Anglo-Saxon advance with any decisive forces. From 919/20 York under the Norwegian Ragnvald became part of a Hiberno-Norwegian power bloc that extended as far as Dublin. Eduards son and successor Æthelstan (king from 925 to 939) took possession of the Kingdom of York in 927 after the expulsion of the Hiberno-Norwegian ruler Guthfrith and in the same year he was allowed by the kings of Scotland, Strathclyde, West Wales ( Cornwall ), Pay homage to Gwent (in Wales ) and the Earldorman of the Anglo-Saxon-dominated northern part of Northumbria, the old Bernicia, in Bamburgh.

An attempt by Olaf Guthfrithsson , the Irish-Norwegian ruler of Dublin, together with the kings of the Scots and Strathclyde, to break the Anglo-Saxon supremacy in the north of England and to re-establish the Dublin-York axis, ended in 937 in the battle of Brunanburh (place unknown, possibly near Bromborough in Cheshire ) with the victory of the Anglo-Saxons under Æthelstan. Only after his death in 939 were Norwegians briefly ruled again in York. However, with the death of Erik Blutaxt in 954 at the Battle of Stainmore, Scandinavian rule in England or parts of it ended by the beginning of the 11th century.

Number of settlers and course of the settlement

Since there are virtually no written sources for evaluating Scandinavian settlement activity in Danelag, the research has not yet reached a generally recognized consensus. Archaeological finds can only partially answer the open questions. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is the only contemporary written source that makes statements about Scandinavian settlements.

“[…] 7 þy geare Healfdene Norþanhymbra lond gedælde. 7 ergende wæron 7 hiera ergende. "

"[...] That year Halvdan divided the Northumbrian land. And they became eggers and plowers. "

Chronicle 877 gives similar indications when another part of the Great Army divided eastern Mercia among themselves. In 879, the last part of the Viking army finally settled in East Anglia after the Vikings occupied and divided it up.

For 892 the chronicle reports that the Great Army from the mainland embarked for England on horses, and in 893 it is said that the English army in the attack on the camp of the Viking army in Benfleet on the Thames estuary handed over to all property of the Danes and to women and Children put. The following year it is reported that the Danes took their wives to safety in East Anglia, and in 896, when the Danish army disbanded, some went to Northumbria, another to East Anglia, and those who were destitute embarked for new ones Looting in the Franconian Empire. When 902 different Irish kings joined forces and defeated and expelled the Vikings from Dublin, they settled in the north-west of England.

The size of the Great Army of 865 is now estimated at around 500 to 3000 men. Given this seemingly small number, it should be borne in mind that the army mostly fought against hastily called up peasant contingents, which had little chance of victory against the militarily tight and battle-tested Vikings. Even the Great Army, which, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, transferred from the continent in two groups of 250 and 80 ships in 892, had far fewer than 10,000 fighters according to current estimates. In order to explain the strongly Scandinavian character of the Danelag, research has assumed a second wave of immigration that settled the country behind the military protective shield of the conquerors. However, it is difficult to prove this assumption.

Etymological traces

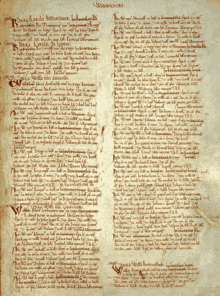

The list of place names, which are listed in the Domesday Book of 1086, serves as a further indication after the sparse written sources for the reconstruction of the settlement activity. The Domesday Book was used by King William the Conqueror (King from 1066 to 1087) to record the services of those lands that belonged to the crown. There are three important different forms of place names of Scandinavian origin:

- Place names of the so-called Grimston mixed type , which consist of an Old Norse personal name and the Old English suffix -tūn , which means something like village or homestead. (Examples: Grimston, Barkston, Thurvaston)

- Purely Scandinavian place names ending in -by (village, homestead). There are almost 800 of them, 200 in Lincolnshire alone . (Examples: Derby, Selby, Danby, Thoresby)

- Places whose names end in -thorpe , which means a remote hamlet, a subordinate settlement. (Examples: Grimsthorpe (Odinsdorf), Scunthorpe, Swainthorpe, Weaverthorpe)

In addition to these name components, there are various other, less common suffixes of Old Norse origin in many place names. Examples of this are names ending in -ey , -bost , -dale , -gate , -kirk or -toft . For the territory of the Five Cities alone, the Domesday Book lists more than five hundred village names of Danish origin.

The older research assumed that the Great Army under its leaders would have settled in large numbers in the areas of the Danelag. The higher concentration of free farmers (socmen) observed in the Danelag was also cited as an argument for a high number of settlers . However, this does not result directly from the different social and economic conditions that the Scandinavian settlers brought with them from their homeland, in contrast to Anglo-Saxon England. Rather, the defensive struggle against the Scandinavian conquerors in the Kingdom of Wessex led to a centralization of administration and a concentration of economic resources. This also included an increased formation of manors with unfree peasants and the resulting decrease in free peasants. In contrast, the Danelag remained politically fragmented among local leaders and independent farmers were more common. And their status was not determined by their origin, but by the type of taxes set: only six of 74 passed farmers mentioned in documents from the 11th century have Scandinavian names.

The considerations on the history of the settlement also go into the spatial distribution of the different types of names in comparison with the agricultural conditions. Places with village names of the Grimston type are mostly on good arable land. These are existing Anglo-Saxon villages that have been renamed by their new Scandinavian owner. The villages of the type with -by seem to indicate a second settlement phase, in which land that was still fallow, but usable, was recorded. The places are far less often on good arable land. Places with the name ending -thorpe , on the other hand, are almost always on the edge of cultivable soil and thus seem to have emerged last. This is also indicated by the use of the -thorpe suffix .

From these findings it was deduced that the Scandinavian settlement took place in two phases: After the conquest and military security of the Danelag in phase one, the land in the Danelag was settled across the board in the second phase through the influx of compatriots. However, since this assumption has great uncertainties, it has not finally been able to prevail. It is not known whether and to what extent there was unused, cultivable land at all at the end of the 9th century. Likewise, it is more likely that the new masters will divide the land among themselves as they see fit, instead of leaving the previous settlement and land distribution structure untouched and building new settlements apart from the existing ones. For a long time it was also considered certain that there must have been an influx of further settlers, since the Scandinavian armies, according to current estimates, comprised only a few thousand men.

Archaeological finds

Cities

Extensive excavations, especially in York and Lincoln, have given insights into the urban culture of the Danelag. The city of York was re-fortified soon after its capture by the Vikings in 866 by repairing the old Roman walls. There seems to have been a strong influx of new settlers as the road network was rebuilt. The numerous streets with the suffix -gate still bear witness to this today. Jetties were built on the banks of the Ouse . Between 1976 and 1981 excavations were carried out at various locations in the old town. On the properties in the Coppergate that were examined, there were rectangular wooden buildings with the gable ends facing the street. Often there was another house used as a workshop behind it. The remains of workshops for woodworking, a jewelry workshop and one of the rare mints with stamps and test mints were found. Finds of textiles, combs, metal products made of bronze, gold, silver and lead, glass beads, wood and leather items reflect the diversity of the craft activities carried out here. The extensive trade connections show various goods originating from abroad, such as silk from Byzantium , wine jugs from the Rhineland, whetstones from Norway, amber from the Baltic Sea and the shell of an exotic cowrie shell from the Red Sea . The importance of York only decreased after the conquest of England by the Normans. On the one hand, trade was oriented more towards the areas around the English Channel and, on the other hand , William I incinerated the city and large parts of northern England after an anti-Norman uprising in 1069. The excavation areas in the Coppergate were conserved after the investigation and opened to the public as the Jórvík Viking Center .

In Lincoln, too, the Scandinavian settlers created a new road network, as excavations have shown. Around 900 they redistributed the space within the old Roman fortifications. As in York, goods from various areas of Europe and the Middle East were found here. The remains of local handicraft production also came to light during the excavations.

In Stamford , typically shaped pottery was made on the wheel, which spread over the area of the Five Castles and at the same time marked its area of influence. During excavations, pots, bowls, jugs, jugs and dishes of this type were found. More valuable versions of this product were glazed.

Rural settlements

Only a small number of rural settlements have been excavated in Danelag and the Kingdom of York. At Ribblehead in Yorkshire ( 54 ° 12 ′ 3.9 ″ N , 2 ° 21 ′ 38.1 ″ W ) a longhouse was found that resembles Norwegian buildings of the same time. Similar structures were also found in other places. There seems to have been a mixture of agriculture and handicrafts everywhere. Here and during further excavations of agricultural settlements, no clear Scandinavian assignment of the former residents could be carried out. In the area of the Five Cities, the remains of long halls surrounded by a fortified enclosure were found in Goltho near Lincoln and in Sulgrave. Here, too, the settlements could not be clearly assigned to the Anglo-Saxon or Danish part of the population. Graves that can be identified as pagan by graves were rarely found. This can be taken as evidence of the rapid Christian assimilation of the settlers.

Culture and religion

The influence of the Scandinavian settlers is also evident in various stone sculptures, which have been preserved better than other material evidence due to their material. The Hogback stones , which were created in the 10th century, are a special form of tombstones : tombstones in the shape of a house with arched side walls and a curved roof ridge. In some specimens, the end faces are formed with bear heads facing each other. The side surfaces are often decorated with pictorial representations or with knot patterns in the Borre style . Hogback stones served the taste of the Scandinavian settlers and are found mainly in Yorkshire (particularly common in the Valley of Teas) and Cumbria up to Scotland. Some specimens have survived to this day in over 30 locations, including Brompton, Ingleby Arncliffe (all Yorkshire), Gosforth (Cumbria), Heysham (Lancashire), West Kirby (Wirral) or Govan and Luss (all Scotland).

Stone crosses were set before the Scandinavian conquest, but the stonemasons' workshops adopted the Scandinavian design language. Representations of Christian religious scenes were mixed with pagan motifs. The 10th century cross of Gosforth in Cumbria, decorated with Borre patterns, which combines a crucifixion scene with representations from the Ragnarök, is a good example of this. The same cross also shows the Irish influence that the Norwegian settlers brought with them to the west coast of England: the ring-shaped cross head is a typical Irish style feature. The Gosforth Cross is the largest surviving work of sculpture in England prior to the Norman Conquest. Other sculptures and crosses such as those in Sockburn (Durham) and Middleton (Yorkshire) show the Scandinavian gentlemen of the Danelag how they would like to see themselves represented: in armor and with weapons.

The emergence of all these tombs and crosses with Christian symbolism in the 10th century shows how quickly the cultural assimilation of the Scandinavians took place. The readiness of the Scandinavian conquerors to accept the Christian faith had already been indicated by Guthrum's baptism in Wedmore in 878. Coins that were minted by the Scandinavian kings of York underline this rapid change. As early as the turn of the 10th century, Christian crosses were used as coin symbols and inscriptions such as Dominus deus omnipotens rex (Lord and God Almighty King). 905 pennies with the legend Sancti Petri moneti (Saint Peter's money) were minted in York . Around 895 a Scandinavian leader was buried in the York Minster according to Christian ritual. And as early as 883 monks who had fled Lindisfarne eight years earlier were able to settle back in Northumbria with peace of mind. The attempts at conquering Dublin by the Hiberno-Norwegian kings represented a certain turning point. On the coins of the kings Ragnvald and Sigtrygg, pagan symbols such as the Thor's hammer are used again in addition to the cross. Olav Sigtryggsson's coins show, among other things, a raven banner . But that was just an episode. Olav died in 981 in seclusion in the monastery of Iona . And with Oswald von York , a grandson of one of the Scandinavians who had come to England at the time of the Great Army became Archbishop of York. He was venerated as a saint soon after his death in 992.

Aftermath

The Scandinavian settlers had a lasting effect on English society in a wide variety of areas of life. The English language was strongly influenced by Danish . The approximately 600 Old Norse loanwords preserved in modern English are not only found in certain domains or special fields of activity, but also widely in every area of English. These include such common words as call < kalla 'call', fellow < félagi 'comrade', loose < lauss 'lose', knife < knífr 'knife', take < taka 'take', window < vind-auga 'window', egg < egg 'egg', ill < íllr 'bad, bad, sick', law <* lagu 'law', give < giva 'give', which have replaced the originally existing Anglo-Saxon expressions. The Scandinavian settlers also changed the language structure. Today's personal pronoun for the third person plural they , them , their < þeir , þeim , þeirra and some prepositions such as from 'von' or til 'bis' can also be traced back to Scandinavian. There are thousands of loanwords in English dialects, especially in the agricultural environment. This indicates that many Scandinavian settlers built their own land and raised their own livestock. The strong linguistic influence is also based on the similarity of many Old Norse and Old English words.

The English kings endeavored by various measures to consolidate the unity of the empire after the conquest of the Danelag. This also included the collection and standardization of legal texts. However, the Scandinavian influence in the areas of the Danelag was so strong that even after the reconquest by the Anglo-Saxons, the different legal traditions of Scandinavians and Anglo-Saxons had to be taken into account. A set of laws drawn up under King Edgar (King from 959 to 975) is the first of several collections of laws that show the differences between the legal usages of Anglo-Saxons and Scandinavians. Around the turn of the millennium, under Edgar's son and successor Æthelred (king from 978 to 1013 and 1014-1016), two separate codices were even published, one for the areas under English law, one for the areas of the Five Cities. An identity of the Danelag area that differs from that of the rest of England can therefore be determined long after the British reconquest. Among the things that the Dane Law knew in contrast to the English Law , for example, was the use of twelve jurors, of whom at least eight had to reach a unanimous verdict. The oath before the court is also based on Scandinavian law. A penance called lahslit for breaking the law existed only in the Danelaw area. The position of the hide as the assessment base for property tax in the Anglo-Saxon part of England was taken by the caracuta in northern Danelag .

It was only recently that researchers at the University of Southern Denmark discovered that a legal work previously regarded as a forgery, which was kept in the private library of a Danish count as Codex Wetmorii , has significant textual similarities with later Jutian law. The text written by a Frater Ejnarius , which was supposed to regulate everyday life in Danelag, can therefore be regarded as an early form of Scandinavian landscape rights of later centuries.

The time of the Great Army was also received in later times in the Scandinavian region. The saga of Ragnar Lodbrok ( Ragnars saga lodbrokar , 14th century) and even more the Krákumál song (end of the 12th century), both of which were written in Iceland, report in a fabulous alienation of it, like the more legendary than historical Ragnar of King Ollle killed in a snake pit in Northumbria. Ragnar's sons Halvdan , Ivar the Boneless and Ubbe then avenge him by invading England and killing the king.

The British film Alfred the Great - Conqueror of the Vikings with David Hemmings as King Alfred the Great and Michael York as Viking leader Guthrum from 1968 tells the story of the defensive battle of Wessex against the Great Army between 870 and 878, but focuses on it on the (fictional) private life of the king. Only the crowd scenes in the battles met with critical acclaim.

The British writer Bernard Cornwell used the events of the Danish attempts to conquer the Kingdom of Wessex as the basis for a series of historical novels, the Saxon Stories , which have been published since 2007. Since 2007 these novels have also been gradually translated into German.

swell

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle . Versions A, B, C, D, E and H (old English original texts) The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (English translation, compiled from different versions)

- Asser: The Life of King Alfred (English translation)

- Thelweard: The Chronicle of Æthelweard . (English translation)

literature

- Heinrich Beck , Henry Royston Loyn: Danelag. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 5, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1984, ISBN 3-11-009635-8 , pp. 227-236.

- Alexander Bugge: The Norse Settlements in the British Islands. In: Transactions of the Royal Historical Society IV (1921) pp. 173-210.

- Clare Downham: Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland. The Dynasty of Ívarr to AD 1014 . Dunedin Academic Press, Edinburgh 2007, ISBN 978-1-903765-89-0 .

- Rüdiger Fuchs: The Scandinavians' conquest of the British Isles from a historical point of view . In: Michael Müller-Wille and Reinhard Schneider (Eds.): Selected Problems of the European Landings of the Early and High Middle Ages I / II . Jan Thorbecke Verlag, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-7995-6641-4 .

- James Graham-Campbell: The Lives of the Vikings . Universitas Verlag in FA Herbig Verlagbuchhandlung, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-8004-1297-7 .

- Simon Keynes: The Vikings in England (around 790-1016) . In: Peter Sawyer (ed.): The Vikings. History and culture of a seafaring people . Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1532-4 .

- Alžbeta Lettowsky: The Vikings: Adventurers from the North . Time-life books. Amsterdam, 1994, ISBN 90-5390-521-9 .

- Felix Liebermann: The laws of the Anglo-Saxons . 3 volumes. Niemeyer, Halle 1903–1916.

- F. Donald Logan: The Vikings in History . Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-15-010342-8 .

- Neil S. Price: The Spread of the Vikings . In: James Graham-Campbell (Ed.): The Vikings . Bechtermünz Verlag im Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1997, ISBN 3-86047-789-7 (series: Bildatlas der Weltkulturen).

- Else Roesdahl: The Vikings . 2nd Edition. Penguin Books, London 1998, ISBN 0-14-025282-7 .

- Peter Sawyer: Kings and Viking. Scandinavia and Europe AD 700-1100 . 6th edition. Routledge. London, 2000, ISBN 0-415-04590-8 .

- Frank M. Stenton: Anglo-Saxon England . (The Oxford History of England Vol. 2). 3rd Edition. Oxford University Press, USA 2001, ISBN 0-19-280139-2 .

- Christian Uebach: The landings of the Anglo-Saxons, the Vikings and the Normans in England. A comparative analysis . Tectum Verlag, Marburg 2003, ISBN 3-8288-8559-4 .

- Horst Zettel: The picture of the Normans and the Normans invasions in West Franconian, East Franconian and Anglo-Saxon sources from the 8th to 11th centuries . Wilhelm Fink, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-7705-1327-4 .

Individual evidence

-

↑ Logan: Vikings . P. 190

f.Christian Uebach: The landings of the Anglo-Saxons, the Vikings and the Normans in England. A comparative analysis . Tectum Verlag, Marburg 2003, ISBN 3-8288-8559-4 , pp. 83 ff.

Alexander Bugge: The Norse Settlements in the British Islands. In: Transactions of the Royal Historical Society IV, 1921, pp. 173-210, p. 184. -

↑ Horst Zettel: The image of the Normans and the Norman incursions in West Franconian, East Franconian and Anglo-Saxon sources from the 8th to 11th centuries . Wilhelm Fink, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-7705-1327-4 , p. 289.

F. Donald Logan: The Vikings in History . Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-15-010342-8 , p. 191. - ↑ The dating is not uniform. While two versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle set the army's stay in East Anglia to 867, all other versions indicate 866 as the year. However, various authors assume that the army moved on from East Anglia that year, supplied with horses, and had landed the year before. For example, the year 865 can be found at: Clare Downham: Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland. The Dynasty of Ívarr to AD 1014 . Dunedin Academic Press, Edinburgh 2007, ISBN 978-1-903765-89-0 , p. 63, in Logan: Wikinger . P. 163, as well as in Uebach: land grabbing . P. 76.

- ↑ a b c The Tironic abbreviation for and is reproduced as 7 .

- ↑ The Chronicle of Æthelweard, IV, 2, 3.

- ↑ Logan: Vikings . P. 164.

- ↑ Flores Historiarum: Rogeri de Wendover , Chronica sive flores historiarum, pp. 298-9. ed. H. Coxe, Rolls Series, 84 (4 vols, 1841-42).

- ↑ Haywood, John. The Penguin Historical Atlas of the Vikings, p. 62. Penguin Books. © 1995.

- ↑ Neil S. Price: The Spread of the Vikings . In: James Graham-Campbell (Ed.): The Vikings . Bechtermünz Verlag im Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1997, ISBN 3-86047-789-7 (series: Bildatlas der Weltkulturen). P. 130.

- ↑ Daniel Weiss: The Viking Great Army, A tale of conflict and adaptation played out in northern England In: archeology.org , March / April 2018, accessed on January 27, 2021.

- ↑ Logan: Vikings . P. 167.

- ↑ Carr, Michael. Alfred the Great Strikes Back, p. 65. Military History Journal. June 2001.

- ↑ Asser, The Life of King Alfred.

- ↑ Felix Liebermann: The laws of the Anglo-Saxons. 3 volumes. Niemeyer, Halle 1903–1916. Vol. I p. 126 f.

- ^ A b Anglo Saxon Chronicle (A, Parker Chronicle), entry for the year 896.

- ^ Anglo Saxon Chronicle (A, Parker Chronicle), entry for the year 893.

- ↑ Price: Propagation . P. 142.

- ↑ On the Norwegian influence, see Allen Mawer: The Redemption of the Five Boroughs. In: English Historical Review 38 (1923) pp. 551-557.

- ↑ Logan: Vikings . P. 191 f.

- ↑ Simon Keynes: The Vikings in England (around 790-1016) . In: Peter Sawyer (ed.): The Vikings. History and culture of a seafaring people . Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1532-4 , p. 102.

- ↑ Price: Propagation . P. 163.

- ↑ Logan: Vikings . P. 163: "The great army that came to East Anglia in 865 counted, according to various estimates, between 500 and 2000 Vikings."

- ↑ Keynes: Vikings . P. 64: “We receive no indication of their size (beyond the fact that they were considered 'large'), and only the strength of their cohesion over several years and the strength of the Her traditional achievements could lead us to believe that she might have comprised between two or three thousand men. "

- ↑ Else Roesdahl: The Vikings . 2nd Edition. Penguin Books, London 1998, ISBN 0-14-025282-7 , p. 234: “ Its size has been much debated, but it is thought to have numbered 2–3,000 men. ”

- ↑ Logan: Vikings . P. 192: "Even the so-called Great Army, which was active between 892 and 896, hardly comprised more than a few thousand soldiers."

- ↑ a b c Uebach: land grabbing . P. 90.

- ↑ a b c d Logan: Vikings . P. 194 ff.

- ^ Roswitha Fischer: Tracing the History of English. A textbook for students . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-534-15135-6 .

- ^ Frank M. Stenton: Anglo-Saxon England . (The Oxford History of England Vol. 2). 3rd Edition. Oxford University Press, USA 2001, ISBN 0-19-280139-2 , pp. 254 ff. "Rank and file" theory.

- ↑ Keynes: Vikings . P. 77.

- ↑ a b Uebach: land grabbing . P. 89.

- ↑ Alžbeta Lettowsky: The Vikings: Adventurers from the North . Time-life books. Amsterdam, 1994, ISBN 90-5390-521-9 , p. 113 ff.

- ↑ a b Price: Propagation . P. 135 f.

- ^ Roesdahl: Vikings . P. 242.

- ↑ Mostly translated as mountain ridge . The word-for-word translation pig back , which also occurs, is likely to be incorrect.

- ↑ Price: Propagation . P. 138.

- ↑ James Graham-Campbell: The Life of the Vikings . Universitas Verlag in FA Herbig Verlagbuchhandlung, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-8004-1297-7 , p. 74.

- ↑ Price: Propagation . P. 139.

- ↑ Lettowsky: Viking . P. 107.

- ↑ St. Peter is the patron saint of York Minster.

- ↑ Logan: Vikings . P. 196 f.

- ^ A b Roesdahl: Vikings . P. 245.

- ↑ Logan: Vikings . P. 195 f.

- ↑ Keynes: Vikings . P. 82.

- ↑ Uebach: land grabbing . P. 92.

- ↑ Steen Casparsen: Codex Wetmorii - en tidlig landskabslov? In: Jyllandsposten (Aarhus), July 14, 2004, p. 35.

Web links

- Website of the Institute for Name-Studies (English)

- Website York Archaeological Trust (English)

- Website Jorvik Viking Center (English)

- Ribblehead Viking farmstead (English)

- Private website about the Vikings in England (German)