World financial crisis

World financial crisis or global financial crisis refers to a global banking and financial crisis as part of the world economic crisis from 2007 . The crisis was, among other things, the result of a speculative inflated real estate market ( real estate bubble ) in the USA. August 9, 2007 is set as the beginning of the financial crisis, because on this day the interest rates on interbank financial loans skyrocketed. The crisis culminated in the collapse of the major US bank Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008. The financial crisis prompted several states to secure the existence of large financial service providers through capital increases of enormous size, primarily through government debt , but also equity . Some banks were nationalized and later closed. The already high national debt of many countries rose sharply due to the crisis, especially in the USA.

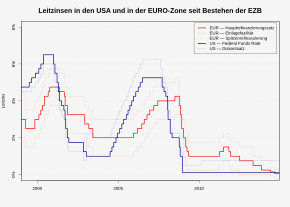

The key interest rates have also been kept low or even further reduced in order to prevent or alleviate a credit crunch . Nevertheless, the crisis subsequently spread to the real economy in the form of production cuts and corporate collapse . Many companies, such as automaker General Motors , filed for bankruptcy and laid off employees. On April 3, 2009, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated global securities losses as a result of the crisis at four trillion US dollars.

The euro crisis followed in 2009 . The trigger is considered to be that the newly elected government of Greece in October 2009 announced that the net new debt in 2009 would not amount to around 6% of GDP (as the previous government intentionally incorrectly stated), but at least twice that amount . 2010 was European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) was established in 2012 and the subsequent European Stability Mechanism (ESM) launched to sovereign defaults to avoid.

causes

The causes of the subprime crisis are discussed controversially, with different causes for the crisis being named. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission appointed by the United States Congress drew up a report on the causes in 2011 after interrogating those involved and sifting through extensive evidence. According to the majority vote of the US Commission, the real estate bubble, boosted by the low interest rate policy , the lax regulation of the banking sector and the lack of regulation of the shadow banks , was primarily a decisive factor in the occurrence and extent of the crisis. The rating agencies are seen as the decisive element that increased the crisis potential considerably. Among macroeconomists will also u. a. The rising inequality of income distribution and the external economic imbalances are discussed as structural causes of the crisis.

Price bubble in the US real estate market

The "Case-Shiller National Home Price Index" recorded a very sharp rise in house prices between the late 1990s and the peak in 2006; an indication of a real estate bubble . Financial players overlooked the price bubble and mistakenly assumed that house prices could not go down over an extended period of time. The homeownership rate in the US was relatively high at 65.7% in 1997 before the real estate bubble. By 2005 the rate rose to 68.9%. The number of homeowners rose by 11.5%. The increase was greatest in the western United States, among people under the age of 35, those with below-average incomes, and among Hispanics and African Americans . The rising real estate prices ensured that even bad investments did not lead to major losses. Gradually, the willingness to issue increasingly risky loans increased. After the lending standards had been softened over the years, after suddenly realizing the actual situation, the reversal (the “Minsky moment” ) followed, after which liquidity on the market dried up and refinancing became impossible in many cases.

Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff saw certain parallels with the property bubbles in Spain, Great Britain and Ireland. In all cases, they believe that price bubbles were the cause of excessive debt accumulation. In the case of the United States, there is also the failure to regulate novel financial institutions; this has made investments in the price bubble even easier.

Growing income inequality

Several economists have identified the rise in income inequality in the US since the early 1980s as a macroeconomic cause . Lower and middle income groups stagnated; some of them financed their expenses through increasing indebtedness. The indebtedness of the lower income groups was politically promoted through the deregulation of the credit markets and through direct state subsidies for housing loans. From this point of view, the subprime crisis was the result of a long-standing macroeconomic instability caused by the increasing inequality of income.

The increasing household debt in the USA had to be financed by loans from abroad. Outside the USA, income inequality also increased sharply (e.g. China, Germany), but here the credit system was less developed or more regulated, so that the lower income groups could not finance their expenditure through loans to the same extent as households in the USA . Thus, the savings of the upper income groups in these countries were invested on the international capital market and thus financed, among other things, the increasing indebtedness of private households in the USA.

Government Home Promotion

According to the minority vote of one of the four Republicans nominated experts for the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission , the changes under Presidents George HW Bush , Bill Clinton and George W. Bush to the Community Reinvestment Act, as well as calls to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac , are more Lending to people with below-average incomes was a major cause of the subprime crisis.

In the opinion of the majority of the named experts, the political guidelines for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were not a major reason for the subprime crisis, since the non-performing subprime loans were predominantly granted by financial institutions that were not subject to government instructions. The mortgage loans issued by government-funded credit banks such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had a significantly lower risk of default than the mortgage loans issued by independent banks (6.2% versus 28.3%). Even the 'Community Reinvestment Act' (CRA) in its current version could not have made a significant contribution to the financial crisis, since only 6% of high-interest loans, i.e. subprime loans, were issued by financial institutions that were subject to regulation by the CRA. In addition, such mortgage loans defaulted only half as often as those that were not subject to the CRA.

Speaking at a conference in 2002 on the low home ownership percentage of the US population, President Bush said:

“We can put light where there's darkness, and hope where there's despondency in this country. And part of it is working together as a nation to encourage folks to own their own home. "

“In this country we can create light where there is darkness and spread hope where there is despair. And part of that is that we as a nation work together to encourage people to own their own homes. "

Bush promoted and cemented the view that owning a home was part of the American Dream . President Obama shared the same view in 2013:

"And few things define what it is to be middle class in America more than owning your own cornerstone of the American Dream: a home."

"And few things better define what it means to belong to the American middle class than having your own foundation of the American dream: a home."

Incorrect credit ratings from rating agencies

According to the majority of the experts of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, the rating agencies have made a decisive contribution to the financial crisis. Without the wrong top ratings, the securitized subprime loans could not have been sold. Joseph Stiglitz described the transformation of F-rated loans into A-rated investment products by the banks in “complicity” with the rating agencies as medieval alchemy . Emails from Standard & Poor’s employees evaluated by the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission suggest that at least some of the employees saw the crisis coming:

"Let's hope we are all wealthy and retired by the time this house of cards falters. :O)"

“Let's hope we are all rich and retired when this house of cards collapses. :O)"

Kathleen Casey of the United States Securities and Exchange Commission pleaded for a regulation of rating agencies in 2009 on the grounds that:

“The large rating agencies helped promote the dramatic growth in structured finance over the past decade, and profited immensely by issuing ratings that pleased the investment banks that arranged these pools of securities, but betrayed the trust of investors who were led to believe that investment grade bonds were relatively safe. "

“The major rating agencies have contributed to the dramatic increase in the volume of structured investment products over the past decade and have benefited immensely from helping investment banks with positive ratings to arrange the pools of securities. In doing so, however, they betrayed the confidence of investors, who were convinced that the investment grade securities were relatively safe. "

On January 14, 2017, the US rating agency Moody’s reached an agreement with the US Department of Justice and 21 states in the legal dispute over embellished credit ratings ; she accepted a share of the responsibility for the global financial crisis in 2008 and a fine of 864 million US dollars.

Shadow banks

The subprime misprices redistributed approximately $ 7 trillion in debt, slightly less than the dot-com bubble that redistributed more than $ 8 trillion in paper assets in 2000. Nevertheless, the financial crisis from 2007 onwards had far more serious consequences than the dot-com crisis. According to the majority of the members of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, the German Advisory Council on Macroeconomic Development, and most economists, the effects of the bursting of the real estate bubble were significantly increased by a structural weakness in the American financial system. Due to loopholes in banking regulation, e.g. B. the subprime loans are transferred to shadow banks, thereby circumventing banking supervision . If the subprime loans had remained on the bank balance sheets, then the banks would have been able to issue far fewer subprime loans because of the obligation to deposit equity and would have had an incentive to check the creditworthiness of borrowers. By transferring the subprime loans to shadow banks, no equity capital had to be deposited, which enabled a much greater leverage effect . Unlike normal banks, shadow banks were not forced to publish figures that would allow conclusions to be drawn about their risk positions, their risk positions were not monitored by banking regulators, there was no deposit insurance for them and the central bank did not initially see itself as a lender of last resort for these non-banks responsible. Therefore, after the real estate bubble burst, the shadow banks experienced a bank run and a credit crunch , as the classic banking sector had last experienced in the global economic crisis from 1929.

Low interest rates after the dot-com stock bubble

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) wrote in its annual report of June 2008 that key interest rates in the advanced countries had recently been unusually low; there was no inflationary pressure. The US central bank Fed operational after the bursting of the dotcom bubble a expansionary monetary policy to the US economy to stimulate (→ Economic Policy ). In June 2003 it lowered the federal funds rate to 1%. When the economy picked up again in mid-2004, the FED began to raise the federal funds rate. Contrary to the intention of the FED, this did not affect long-term interest rates.

Chinese and Japanese currency interventions

The low interest rates did not lead to a devaluation of the US dollar because the “emerging economies” intervened against an appreciation of their currencies by easing their monetary policy ( Bretton Woods II regime ). China bought $ 460 billion in 2007. The currency reserves of China and the industrialized state of Japan , which pursued a similar strategy, thus rose to at least 1 trillion each. U.S. dollar. To promote its export, Japan has kept the key interest rate very low for years, which keeps the rate of the Japanese currency low. Investors used this to take out cheap loans in Japan and thus buy up assets in other economic regions. In addition, the central banks invested the currency reserves created by the foreign exchange market interventions in US government bonds. These foreign exchange market interventions set monetary policy impulses for global credit growth.

In a minority vote, 3 of the 4 experts nominated by the Republicans for the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission saw the great demand of the Chinese and the oil states for American government bonds as a major reason for the financial crisis.

Thesis of a savings glut

High global savings searched for yield in financial markets and led to an underestimation of the risks ( "saving glut" or associated with loans global saving glut ).

Course and consequences

Overview of the course of the US real estate crisis and its effects

|

Expansion of lending

Due to the increasing demand, the prices of real estate and thus their value as collateral rose. With real estate prices rising steadily, the real estate could have been sold at a higher market value in the event of insolvency. The banks took advantage of this development to sell the debtors additional loans. Customers with poor credit ratings also received loans. The banks were protected against rising prices and debtors believed that they could sell their houses at a profit in an emergency. Some banks specialize in subprime loans (second-rate mortgage loans) and NINJA loans , the abbreviation stands for no income, no job or assets . The later enacted Dodd – Frank Act is intended to curb this predatory lending , which is viewed as improper .

The real estate boom stimulated the construction industry and consumer demand. In 2005, residential construction investments in the USA reached a high of over 6 percent of the gross domestic product , surpassing the record level of 1960 for the first time. In 1991 this share had reached a low of 3.5 percent. After 2005 this proportion then decreased again.

The expansion of lending to bad credit borrowers had two main reasons:

- Lenders believed in ever increasing house prices. Therefore, it did not seem to matter whether the borrowers could make the payments. If they could not, there was either the option of using the increased property value to extend another mortgage loan, or selling the property for a profit and paying off the mortgage.

- Most subprime loans were resold anyway (see Spread of Subprime Loans ), so the risk was borne by the buyer, not the original lender.

Spread of subprime lending

The spread of subprime lending made an important contribution to the extent of the crisis. In contrast to other financial institutions, at least the banks were subject to the regulatory capital requirements. If the banks had kept the subprime loans, they would have had to deposit a certain proportion of their equity for this purpose (see core capital ratio ). Then the banks would have been able to issue much fewer subprime loans and would have had a greater incentive to check the creditworthiness of borrowers more strictly. Instead, more than 90% of the portfolios, which consisted of 100% subprime loans, were structured into apparently first-class investments with the help of rating agencies. The structuring enabled the actually third-rate US mortgage loans to banks and insurance companies as well as their customers to be spread both in the USA and abroad.

Securitisations in the United States

- Securitization of US mortgage loans: A special purpose vehicle (usually a shadow bank) bought a portfolio of subprime loans from the parent bank. The future interest and principal payments of the mortgage debtors were then sold as structured investments in the form of collateralized debt obligations (CDO) in several tranches. The tranches were structured in such a way that all payment defaults were initially at the expense of the equity tranche. Should there be any further payment defaults, the mezzanine tranche would go away empty-handed. The senior tranche would only be affected by defaults if the equity tranche and the mezzanine tranche suffered a total loss. In order to be able to sell the CDOs, the sellers had these securitisations assessed by rating agencies with regard to their creditworthiness. The agencies - almost always commissioned by the securitizing banks - worked closely with them with the aim of structuring the securitization and thus obtaining the largest possible tranches with a good rating (see also Credit Enhancement ). For the risk assessment, the rating agencies used data that went back only a few years and thus only covered the extremely good weather period in the high phase of the real estate bubble. Based on this data, 80% of a portfolio of questionable subprime loans was assigned to the senior tranche and given an AAA rating, i.e. a securitization with a negligible default risk.

- Second-level securitisations: In a further step, the inferior CDO tranches (equity and mezzanine tranches) were again brought into special-purpose vehicles and structured as second-level CDO securitisations. With the renewed help of the rating agencies, a portfolio with a poorer rating could predominantly be transformed into CDOs with a first-class AAA rating.

Further action by European banks

- Second-level securitisations were a means for European banks in particular to participate in the high-commission securitization business. These banks did not have good access to American mortgage loans. That is why they resorted to CDOs to bundle them into packages and re-securitize them in the second stage.

- In order to be able to circumvent banking supervisory rules on risk diversification and security through equity capital , the structured (long-term) mortgage loans were transferred to special-purpose vehicles belonging to the bank by means of a conduit . These are known as shadow banks because they do bank-like business without being subject to banking regulation. The special purpose vehicles financed the purchase by issuing commercial papers with a short term. Capital could be acquired from short-term oriented investors (e.g. money market funds) through the commercial papers. Since this maturity transformation carried the risk of not receiving any follow-up refinancing when the issue came due, the parent banks had to provide guarantees in the form of liquidity lines that protected the commercial paper investor from losses when the paper matured. These guarantees were usually given on a rolling basis with a term of 364 days, since the banking supervisory rules prior to the entry into force of Basel II did not require equity capital for such off-balance sheet obligations with a term of less than one year. Income could therefore be generated without having to draw on regulatory capital. After the real estate bubble burst in July / August 2007, nobody was willing to buy commercial papers from shadow banks. It was also no longer possible to sell the structured mortgage loans. The special purpose vehicles made use of the liquidity lines of their parent banks (see e.g. IKB Deutsche Industriebank , Sachsen LB ). The parent banks had to write off these loans because of the lack of solvency of the shadow banks.

Defaults on subprime loans

The economic slowdown in the USA from around 2005, falling growth rates in labor productivity in the USA and other countries, especially in the construction industry in the USA, and the later rise in the US base rate to up to 5.25% in June 2006 triggered one Chain reaction. Low-income borrowers could no longer pay the increased installments on their adjustable-rate loans and had to sell their home. Due to the increasing real estate sales, house prices collapsed (peak was July 2006) and due to the falling value of real estate, banks and investors increasingly had unsecured loan claims. The insolvency of debtors now resulted in losses for banks and investors.

In the spring of 2007, defaults on subprime loans in the United States reached their highest level in recent years. Some real estate funds that had invested in structured financial products suspended the acceptance of fund units because otherwise they would have got into financial difficulties. In June 2007, Bear Stearns informed the customers of two of its hedge funds that the deposits, which had been valued at $ 1.5 billion at the end of 2006, were now worth next to nothing. Dozens mortgage lender, which had just specialize in these loans had bankruptcy protection apply.

Overall, in October 2008 the International Monetary Fund estimated the value of subprime mortgages to fall by 500 billion US dollars and that of prime mortgages to a further 80 billion dollars. The Scientific Advisory Board of the Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology does not consider this sum to be very large compared to the size of the global financial market. According to the IMF estimate from October 2008, the loss in value of the mortgage-backed securities of US $ 500 billion is significantly higher than would actually be expected from defaults on the underlying mortgages. The sharp drop in the price of mortgage-backed securities was due to the fact that buyers, out of caution, no longer wanted to buy these securities at lower prices. The complexity and lack of transparency of these securities as well as the fact that many securities were traded over the counter , so that a market price formation and thus a valuation of the paper was difficult at all , contributed to this caution .

Effects on the financial markets

In April 2009 the IMF estimated the total losses at 4.1 trillion US dollars (approx. 3 trillion euros). Of these, the losses from "toxic" US papers are around 2.7 trillion US dollars, the losses from European papers are estimated at around 1.2 trillion US dollars, and Japanese papers at 150 billion US dollars. In August 2009, the IMF increased its calculations to $ 11.9 trillion, almost tripling.

Banking crisis

The losses in value of the subprime loans and the structured securitisations went directly into the bank balance sheets and reduced the banks' equity. In order to be able to meet the regulatory requirements for equity reserves or to keep the ratio of equity to receivables stable at all, the banks were forced to either raise new equity or sell other assets, which lowered their prices. This deleveraging - the banks had to sell a multiple of their assets when the value of receivables fell in order to restore the old ratio of equity to receivable volume - led to the "implosion of the financial system since August 2007".

Investors included not only risk-taking hedge funds, but also more conservative investment funds . However, since hedge funds in particular had invested heavily in the more risky securities tranches, losses were incurred, which in some cases led to the closure and liquidation of the hedge funds. But investment banks were also affected. The shutdown of hedge funds and losses at investment banks led to a decline in investor risk appetite. They then withdrew considerable amounts from the capital market in a short time or held back with new investments in high-risk assets.

The decreasing willingness of investors to take risks brought the refinancing of the special purpose vehicles established by banks to a standstill. The trigger for the crisis was that from July 2007 the owners of the commercial papers were no longer willing to buy them again when they were due. The short-term loans were not extended any further. This put the special purpose vehicles under pressure. However, they were also no longer able to sell the structured securities because they could no longer buy them. Therefore, the special purpose vehicles now had to fall back on the loan commitments of the banks. In the timing of the SVR , "Phase I" of the financial crisis began.

Crisis of confidence in the interbank market

Due to the confusion of the shadow banking system (the postponement of securitisations in special-purpose vehicles, sale of securitisations with repurchase agreements, etc.) nobody was initially able to assess the full extent of the crisis and the remaining solvency of the banks. This contributed to the confidence crisis between the banks, which was reflected in the money market by an increase in money market interest rates. On August 9, 2007 - this day is now considered to be the beginning of the actual financial crisis - the premiums for interbank loans rose sharply compared to the central bank rate worldwide, especially in the USA. With the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008, after a state rescue failed, the interbank market came to a standstill worldwide. Short-term excess liquidity was no longer invested with other banks, but with use of the deposit facility at the central banks.

In the timing of the SVR , "Phase II" of the financial crisis began.

Increase in risk premiums on government bonds

In the course of the crisis, the national debt of many countries continued to rise, for example because of measures to stabilize the banks and economic stimulus programs ("Phase III"). The risk premiums of various European countries compared to German government bonds rose. Several countries in the eurozone were only able to maintain their solvency through international aid loans ( euro crisis ). As part of the European Stabilization Mechanism , a joint loan package from the EU , euro countries and the IMF with a total of 750 billion euros was agreed. The European Central Bank also announced that it would buy up government bonds from the euro countries in an emergency.

Effects on the real economy

In the course of 2008, the financial crisis increasingly affected the real economy. Effects could first be seen in the USA, then in Western Europe and Japan, and since autumn 2008 all over the world. As a result, share prices worldwide recorded a second sharp decline from October 2008 after a first slump due to the financial crisis for fear of effects on the real economy. On the raw material markets , too, prices fell sharply, especially from the beginning of the fourth quarter of 2008. Most automobile manufacturers in the industrialized countries announced significant production cuts at the end of October / beginning of November in order to respond to sales slumps in the double-digit range. According to the findings of the Federal Statistical Office , Germany found itself in a recession after two quarters of negative growth rates compared to the corresponding quarters of the previous year between October 2008 and the 2nd quarter of 2009 . According to Eurostat statistics, industrial production in the euro area fell by more than 20% from its peak in spring 2008 to spring 2009. The decline in industrial production is thus comparable to that in the first year of the Great Depression in 1930 in Germany and the USA.

A study by Deutsche Bank Research put the crisis-related reduction in world GDP at four trillion US dollars.

The financial crisis also had a significant impact on companies' ability to forecast. Due to the unpredictability of the markets, many listed companies had difficulties formulating the forecasts for the coming financial year required for their annual reports in the management report in accordance with Section 289 of the German Commercial Code . The companies had to walk a tightrope here. On the one hand, a forecast had to be made in order to inform investors in accordance with the legal regulations, on the other hand, quantitative targets were difficult to quantify. The trend was towards forecasts that were based on various scenarios and were predominantly qualitative. Companies that continued to communicate quantitative data in their forecasts were allowed by the capital market to indicate larger ranges of up to 20%.

Hunger crisis

It is believed by researchers that the 2007-2008 food price crisis is related to the global financial crisis. In addition to factors that are independent of the economic crisis, a. the increased switch to staple food speculation in the wake of the financial crisis linked to the hunger crisis. According to Welthungerhilfe and Oxfam as well as individual experts from UNCTAD and the World Bank , the crisis was mainly due to speculative transactions in food. However, this view was also partly contradicted.

As the FAO noted in 2009, the number of starving people had risen by 100 million (a total of 1 billion) since the outbreak of the crisis. This was justified with the economic crisis in general and the high food prices in particular.

Assessment of the duration and extent of the crisis

The global financial crisis has led to significantly slower economic growth or to a recession almost everywhere in the world. According to the IMF, the real gross domestic product (GDP) of the economically developed countries contracted in 2009 for the first time since the Second World War, by 3.4 percent compared to the previous year. Worldwide, real GDP growth in 161 countries in 2009 was below the 2007 figure. In only 29 countries it was higher in 2009 than in 2007 - above all countries with little integration into the world market and relatively low GDP per capita. In 2007 real GDP growth in 147 countries was at least 3.0 percent. In 2009 this only applied to 61 states.

In terms of trade in goods, the global financial and economic crisis led to the sharpest decline since 1950. Real goods exports fell by 12.4 percent between 2008 and 2009. However, the crisis-related decline could already be compensated for in 2009/2010, as real goods exports increased by an above-average 14.0 percent between 2009 and 2010. Between 2010 and 2017 it increased by a further 22.9 percent - most recently by 4.5 percent from 2016 to 2017.

On the global stock markets, the average turnover rate of stock trading increased significantly during the crisis: it more than doubled from 2007 to 2008 - stock trading continued to grow (from 104.1 to 120.1 trillion US dollars) and market capitalization decreased dramatically (from $ 60.7 trillion to $ 32.4 trillion). While the consequences of the financial crisis outside the financial sector in 2009 were many times greater than in 2008, the development on the financial markets in 2009 was a little quieter than in the previous year: the market capitalization rose from 32.4 to 47.0 trillion US dollars (2017: 85.3 Trillion US dollars) and stock trading decreased from 120.1 to 89.0 trillion US dollars (2017: 117.3 trillion US dollars).

The public debt of the EU rose sharply in the course of the crisis: after the debt level had decreased in the period 1996–2007 and increased comparatively slightly from 2007 to 2008 from 57.5 to 60.8 percent of GDP, the corresponding value rose to 73.4 percent in 2009 and 78.9 percent in 2010. In the following years, Europe's debt crisis widened further: between 2010 and 2014, the debt level of the EU-28 rose four times in a row from 78.9 to 86.5 Percent of GDP. However, it has fallen three times since then and stood at 81.6 percent of GDP in 2017.

The global financial and economic crisis also had serious consequences on the EU labor market: Between 2004 and 2008, the unemployment rate in the EU-28 fell four times in a row, falling from 9.3 to 7.0 percent. However, the crisis ended this development abruptly: In 2009 the unemployment rate was 9.0 percent and then rose further to 10.9 percent in 2013. However, the unemployment rate in the EU-28 fell in 2017 for the fourth year in a row - to 7.6 percent.

In 2019, more than ten years after the start of the global financial crisis, according to the head of the Austrian Financial Market Authority, Helmut Ettl, despite all the activities, by far not all problems and risks in the underlying financial market sector have been resolved. As a result, there are signs of a new “geopolitical recession” in light of the persistently low interest rates, the global trade dispute, the conflicts in the Arab world, the ongoing threat of a disorderly Brexit and the crisis of multilateralism, which is being replaced by multi-nationalism " in the room.

International countermeasures

Coordination of central banks

Since December 2007, the European Central Bank (ECB), in consultation with the US Federal Reserve , has been making US dollars available to the banks and accepting euro-denominated securities as collateral in order to ease the situation on the money market. In this respect, the ECB assumes the private banks' exchange rate risks.

On December 11, 2007, the US Federal Reserve cut its key interest rate for the third time since September 2007 . In a concerted action on December 12, 2007, five central banks announced further measures to counter the "increased pressure on the short-term financing markets". Among other things, the Federal Reserve lent in a barter transaction ( swap ) the European Central Bank (ECB) 20 billion dollars and the Swiss National Bank 4 billion dollars, in order to counteract the dollar shortage in Europe. According to the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , it has become known from the minutes of the meetings of the Fed's Open Market Committee, which have since been published, that the initiative for these dollar loans from the Fed to the ECB came from the Fed.

On September 18, 2008, central banks around the world made a concerted offer of more than $ 180 billion to ease tensions in the money market . At the European Central Bank, the banks were able to borrow up to 40 billion US dollars for a day on Thursday, September 18, 2008, plus a euro quick tender with an open volume. The Bank of Japan is offering US dollars for the first time.

From October 2008, seven of the leading central banks, including the Federal Reserve (Fed), the European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of England (BoE) and the Swiss National Bank (SNB), lowered their key interest rates in a concerted effort . Since then, further interest rate cuts have taken place, bringing key interest rates to a level that has not been reached in decades, sometimes to an all-time low.

On April 6, 2009, the ECB provided the Fed with a swap line amounting to 80 billion US dollars in euros , the British central bank granted 60 billion pounds , the Swiss central bank 40 billion francs and the Japanese central bank 10 trillion. Yen available. In the future, US credit institutions will be able to use the Fed to access loans in foreign currencies. The measure of the central banks complements the measures of September 18, 2008 in the opposite direction. At that time, the Fed had granted foreign central banks swap lines totaling US $ 300 billion.

On November 30, 2011, the European Central Bank , the US Federal Reserve , the central banks of Canada, Japan, Great Britain and the Swiss National Bank made more money available to the global financial markets to stave off the debt crisis and support the real economy. The central banks agreed to reduce the cost of existing dollar swaps by 50 basis points from December 5, 2011. They also agreed to exchange deals so that the currency required by banks can be provided at any time. The central banks thus guarantee the commercial banks that they are also liquid in other currencies. At the same time, the Chinese central bank eased its monetary policy. In October 2013, the European Central Bank (ECB), the US Federal Reserve , the Bank of Japan , the Bank of England , the Bank of Canada and the Swiss National Bank announced that they would permanently maintain the December 2007 swap agreements.

Economic stimulus programs

In many countries, extensive economic stimulus programs and financial market stabilization laws were introduced as part of the financial crisis . In the US, there are the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 (ESA scope: US $ 150 billion), the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (EESA scope: US $ 700 billion) and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA scope: $ 787 billion). In Germany, it is the Financial Market Stabilization Act (scope of FMStG: 400 billion euros), the package of measures "Securing jobs by strengthening growth" (scope of economic stimulus package I: 50 billion euros) and the economic stimulus program "Resolute in the crisis, strong for the next upswing" (scope of the economic stimulus package II: 14 billion euros). In order to stabilize employment, the options for short-time work have been expanded. In Austria, the economic stimulus packages I and II and the tax reform in 2009 (a total of almost twelve billion euros) were introduced.

According to a study by Deutsche Bank Research, the total volume of economic stimulus programs spread over several years is around 2,000 billion US dollars worldwide. According to DB Research, the decline in gross domestic product would have been considerably greater without the programs . The study puts the crisis-related reduction in GDP at "4,000 billion" US dollars. After all, the banking sector can only be restructured slowly.

Measures to stabilize the banking system

In the context of the crisis, (temporary) emergency nationalizations were carried out in the USA and Europe and so-called bad bank concepts (settlement banks ) were introduced. In Germany, the Financial Market Stabilization Development Act of October 17, 2008 and the Financial Market Stabilization Fund (SoFFin) created the possibility of setting up a decentralized bad bank for individual credit institutions . This is supposed to take up problematic structured securities or to wind up entire loss-making business areas of banks in need of restructuring. Support measures in favor of financial institutions increased the gross government debt level in 2008 and 2009 by a total of 98 billion euros. Since these are mainly loans, there are corresponding claims on the financial institutions.

Since October 2008, bank bonds around the world have increasingly been guaranteed by the state. By October 2009, the volume of government-guaranteed bank bonds had reached around 800 billion US dollars. Western Europe accounts for over 450 billion US dollars, with the rest largely in the USA.

In order to stabilize the banking system in the euro zone , the European Central Bank launched a Pfandbrief purchase program , the “ Covered Bonds Purchase Program ”, abbreviated CBPP, and thus acquired securities worth 60 billion euros by June 2010.

The financial upheavals in Central Europe and Austria at that time were considerable. Helmut Ettl sums up the situation at the time as follows: “The two most important refinancing banks, Swiss UBS and Credit Suisse, almost blew up after the Lehman bankruptcy. This meant that the Swiss franc market for commercial banks had dried up overnight and there would have been no follow-up financing. ”The resulting very dramatic plight of the Austrian and subsequently Central European banks was only able to take place in countless rush conferences of the Austrian FMA these days , Oesterreichische Nationalbank (OeNB), ECB and Swiss National Bank will be restored.

According to Joaquín Almunia , Vice President of the EU Commission, between October 2008 and March 2010 state aid amounting to around 4 trillion euros was approved, three quarters of which in the form of state guarantees. The banks actually took 994 billion euros from the state guarantees.

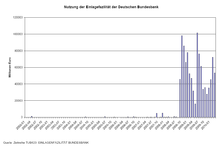

According to the Deutsche Bundesbank , the gross debt of the state in Germany ( local authorities and social security, including the extra budgets to be allocated) rose to 83.2 percent of GDP (almost 10 percentage points) at the end of 2010 as defined by the Maastricht Treaty . This would reflect extensive measures to stabilize the financial markets in the amount of 241 billion euros, which were primarily related to Hypo Real Estate and WestLB . Since 2008, as part of these financial market support measures, the national debt level has risen by 335 billion euros, which corresponds to 13.4 percent of the gross domestic product . Insofar as the assumed risk assets could be used in the future, the debt level would fall again.

According to Joaquín Almunia , governments of the European Union used 1.6 trillion euros (13 percent of GDP) between 2008 and 2010 to bail out their banks. Three quarters or almost 1.2 trillion euros of this aid was used for guarantees or liquidity support, the remaining 400 billion euros for capital aid and necessary depreciation.

A study by Beatrice Weder di Mauro and Kenichi Ueda comes to the conclusion that the value of unspoken state guarantees for the banks has increased in the course of the financial and banking crisis, which leads to financial relief for the banks.

In the period from 2008 to 2011, the countries of the European Union supported the banking industry with 1.6 trillion euros. A number of new regulations have also been passed at national level, particularly in France, and at European level. The EU standardized and tightened various aspects of banking law. In particular, this includes the obligation of financial institutions to develop resolution plans in advance in the event of bankruptcy, as well as early intervention powers and the right for supervisory authorities to appoint special administrators for banks. Critics, especially independent and green MEPs , criticize the measures as inadequate, the behavior of the dominant conservative and socialist European parties as being finance-industry-friendly, and the lack of regulation in important areas such as shadow banking.

Reform proposals from the G-20 countries

Summit in November 2008

Under the acute impact of the financial crisis, a meeting of the heads of state and government of the G20 countries (plus the Netherlands and Spain) took place in Washington from November 14 to 16, 2008 to discuss and implement the fundamentals of a reform of the international financial markets . This high-level meeting was also called the World Financial Summit in the German-language press . The aim was to agree international regulations in order to avoid a repetition of a financial crisis. A catalog with almost 50 individual measures was adopted. 28 of these individual proposals should be implemented by March 31, 2009, the other points in the medium term. The participants clearly rejected tendencies towards protectionism , they explicitly acknowledged the principles of a free market and open trade. In addition, more effective regulation of the financial markets was called for. Among other things, the following measures were agreed:

- better monitoring of rating agencies ,

- stricter regulation of speculative hedge funds and other previously unregulated financial products,

- Definition of valuation standards for complex financial products,

- Increasing the equity buffers of financial institutions,

- Harmonization and revision of accounting rules,

- Orientation of the incentive systems of managers to medium-term goals,

- Protection against unfair competition by draining tax havens ,

- Strengthening the International Monetary Fund ,

- better consumer protection through more transparent information.

Each participating country undertakes to implement the measures in national law.

Subsequent summits

A follow-up conference took place on 1/2. April 2009 in London. In addition to specifying various points from the first meeting, additional measures to stimulate the economy were adopted:

- The G20 countries decided on a program worth 1.1 trillion US dollars to stimulate the world economy, in particular world trade, and to improve the situation in developing countries. In detail:

- The funds for the IMF are to be increased to 750 billion US dollars.

- US $ 250 billion is to be allocated to new special drawing rights .

- An additional at least 100 billion US dollars are to be granted via multilateral development banks .

- By the end of 2010 there should be a fiscal policy expansion of 5 trillion US dollars, which, according to the G20, should give world production an impulse of 4%. However, critics argued that this amount was simply money that had been released by the participants before the conference. Others spoke of an "inventory" and also considered the number to be excessive. According to the IMF, the global gross domestic product that has not been price-adjusted increased by 5.1% between 2009 and 2010.

- To combat tax havens and money laundering, the OECD has published a black list (Costa Rica, Malaysia, Philippines, Uruguay) and a gray list of countries.

- Reforms and a strengthening of the international financial institutions, especially the IMF and the World Bank , were decided.

- Measures for the systematic regulation and monitoring of hedge funds and similar financial investment constructions were specified.

- The goal of strengthening the equity base of credit institutions, which was already declared in November, was supplemented by specific measures.

- It was agreed that manager remuneration should not be based on short-term success, but on long-term goals.

- The commitment to free trade was reaffirmed.

At the other G20 meetings on 24./25. September 2009 in Pittsburgh and on 26./27. June 2010 in Toronto , the priorities remained on reforming and strengthening the financial systems and regaining strong economic growth. In addition, there was the demand for sustainability and balance in achieving the growth targets.

EU reform proposals

On February 16, 2013, Regulation (EU) No. 648/2012 (Market Infrastructure Regulation) came into force, which prescribes settlement via clearing houses and reporting to a trade repository for off-exchange derivatives trading .

In 2014, the European Banking Union was adopted, with which a single banking supervisory mechanism and a single bank resolution mechanism became effective. As the final component of the regulatory framework for the European banking system, Internal Market Commissioner Michel Barnier presented a proposal for a structural reform of the banking system on January 29, 2014, based on the report of a group of experts chaired by Erkki Liikanen .

After the presidency of the Commission had changed from José Manuel Barroso to Jean-Claude Juncker , this proposal by the EU Commission failed on May 26, 2015 in the Economic Committee of the European Parliament .

In June 2015, the EU finance ministers voted unanimously in favor of separate banking rules . The next step is for the European Parliament to draw up a position, after which negotiations between the European Council and the European Parliament will take place, but these seem to be stalling.

The Commission proposal proposes a ban on proprietary trading and other high-risk trading activities are to be relocated to legally independent institutions. In addition to the proposal, the Commission has adopted accompanying measures to promote the transparency of certain transactions in shadow banking .

Documentaries and feature films

- Inside the Meltdown, Documentation, 2009

- Capitalism: A Love Story , documentary by Michael Moore, USA 2009

- Company Men , feature film, USA 2010

- Inside Job , documentary by Charles H. Ferguson, USA 2010

- Wall Street: Money never sleeps , feature film, USA 2010

- The big crash - Margin Call , feature film, USA 2011

- Too Big to Fail , feature film, USA 2011

- Money, Power & Wall Street, Documentation, 2012

- Assault on Wall Street , feature film, Canada 2013

- Master of the Universe - Der Banker, documentary by Marc Bauder, Germany / Austria 2013

- The Big Short , feature film, USA 2015

See also

- List of the highest penalties against banks

- Global financial system

- Chronology of the financial crisis from 2007

literature

- Ben S. Bernanke : The Courage to Act: A Memoir of a Crisis and Its Aftermath. WW Norton & Company, New York City 2015, ISBN 978-0-393-24721-3

- Markus K. Brunnermeier: Deciphering the Liquidity and Credit Crunch . In: Journal of Economic Perspectives , Vol. 23, No. 1, Winter 2009, pp. 77-100 ( PDF; 240 kB ).

- United Nations General Assembly : The Commission of Experts of the President of the UN General Assembly on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System (“Stiglitz Commission”).

- Stuart Jenks : Banks and Financial Crises , Vlg. Schmidt-Römhild, Lübeck 2012, ISBN 978-3-7950-4512-8 .

- Max Otte : The financial crisis and the failure of the modern economy , in: From politics and contemporary history 52/2009, pp. 9-16.

- Susanne Schmidt : Market without Morals - The Failure of the International Financial Elite , Vlg. Droemer Knaur, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-426-27541-2 .

- The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC): The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report , January 2011, ISBN 978-0-16-087727-8 (also online: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-FCIC/ pdf / GPO-FCIC.pdf PDF, 5.5 MB)

- Falk Illing : Germany in the Financial Crisis, Chronology of German Economic Policy 2007–2012 , Vlg. Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-531-19824-8 .

- Martin Wolf : The Shifts and the Shocks. What We've Learned - and Still Have to Learn - from the Financial Crisis . Penguin Books, New York City 2014, ISBN 978-1-59420-544-6 .

- Nomi Prins : Collusion: How Central Bankers Rigged the World , Nation Books 2018, ISBN 978-1-56858-562-8 .

- Adam Tooze : Crashed. How ten years of the financial crisis have changed the world , Siedler, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-8275-0085-4 .

Web links

- Martin Hellwig : Systemic Risk in the Financial Sector: An Analysis of the Subprime-Mortgage Financial Crisis (PDF; 786 kB), Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, Bonn, November 2008.

- Bank for International Settlements : Current Statements from Central Bankers . BIS, 79th Annual Report 2009

- OECD : Financial Market Trends

- Barry Eichengreen, Kevin H. O'Rourke: A Tale of Two Depressions, VoxEU.org, 2009.

- Halle Institute for Economic Research : Special Issue: World Financial Crisis (PDF; 14.0 MB) from March 31, 2009 (accessed on June 25, 2009).

- Deutsche Bundesbank: Financial Stability Report 2009, Frankfurt am Main, November 2009 (PDF)

- Ralf Hoppe, Beat Balzli, Hauke Goos, Jochen Brenner, Frank Hornig, Ulrich Fichtner, Ansbert Kneip and Klaus Brinkbäumer: The bank robbery . In: Der Spiegel , November 17, 2008 ( Awarded the Henri Nannen Prize for particularly understandable and descriptive documentation of a complex current or historical issue)

- Global financial crisis on the information portal for political education

- Graphic: Global financial and economic crisis , from: Figures and facts: Globalization , Federal Agency for Civic Education / bpb

- Political science literature on the subject of the global financial crisis in the annotated bibliography of political science

- "Development of the financial market crisis - From the US subprime crisis to the bad bank law Federal Ministry of Finance" Germany December 22, 2009

- Graphic: Unemployment in Europe after the financial and economic crisis , from: Figures and facts: Europe , www.bpb.de

- Gerhard Strate , Criminal Law Processing of the Financial Crisis [2]

- Inside the Meltdown 4-part PBS documentation on the financial crisis, as well as additional background articles and detailed expert interviews (English)

- Money, Power & Wall Street 4-part stationery documentation on the financial crisis, as well as additional background articles and detailed expert interviews (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dorothea Schäfer, "Borrowed trust even after ten years of continuous financial crisis" in diw weekly report August 9, 2017 [1]

- ↑ a b Four trillion dollars in damage from crisis . In: Salzburger Nachrichten . April 22, 2009, p. 15 ( article archive ).

- ↑ IMW: International Financial Stability Report , April 2009, Chapter 1: Stabilizing the Global Financial System and Mitigating Spillover Risks (PDF; 1.8 MB), Table 1.3.

- ^ The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report , FCIC, January 2011

- ^ Robert J. Shiller , The Subprime Solution: How Today's Global Financial Crisis Happened, and what to Do about it , Princeton University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-691-15632-3 , Introduction, pp. Xii

- ^ Robert J. Shiller : The Subprime Solution: How Today's Global Financial Crisis Happened, and what to Do about it , Princeton University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-691-15632-3 , p. 5

- ↑ Kristopher S. Gerardi, Andreas Lehnert, Shane M. Sherland, Paul S. Willen, Making sense of the subprime crisis , Working Paper, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, No. 2009-2, p. 48

- ↑ Bank for International Settlements , 78th Annual Report, p. 8

- ↑ Carmen M. Reinhart, Kenneth S. Rogoff: Is the 2007 US sub-prime financial crisis so different? An international historical comparison , 2008, American Economic Review 98, No. 2, pp. 339–344, here pp. 342–344 doi: 10.1257 / aer.98.2.339

- ^ How income inequality contributed to the Great Recession The Guardian, Till van Treeck, May 9, 2012

- ↑ Leveraging Inequality International Monetary Fund, Michael Kumhof and Romain Rancière of December 2010

- ↑ See Robert Reich: Aftershocks - America at the turning point Campus-Verlag , Frankfurt New York 2010, ISBN 978-3-593-39247-9 .

- ↑ See Raghuram Rajan: Verwerfungen, Finanzbuch Verlag, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-89879-685-9 .

- ↑ See Joseph Stiglitz: The price of inequality. How the division of society threatens our future. Siedler, Munich 2012, ISBN 3-8275-0019-2 .

- ^ Till van Treeck, Simon Sturn (2012): Income inequality as a cause of the Great Recession? A survey of current debates . ILO Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 39

- ↑ Unequal = Indebted International Monetary Fund, Michael Kumhof and Romain Rancière from September 2011

- ↑ a b Hermann Remsperger : madness the abyss , FAZ.net May 2, 2011

- ^ The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report: Final Report of the National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in the United States , Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission , p. Xxvi

- ^ The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report: Final Report of the National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in the United States , Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission , p. Xxvii

- ^ A b President Hosts Conference on Minority Homeownership. In: archives.gov. Office of the Press Secretary, October 15, 2002, accessed January 29, 2016 .

- ↑ International Business: Bush drive for home ownership, fueled housing bubble. In: nytimes.com. Jo Becker, Sheryl Gay Stolberg, Stephen Labaton, December 21, 2008, accessed January 29, 2016 .

- ^ Weekly Address: Growing the Housing Market and Supporting our Homeowners. In: whitehouse.gov. Office of the Press Secretary, May 11, 2013, accessed January 29, 2016 .

- ^ The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report: Final Report of the National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in the United States , Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission , p. Xxv

- ↑ Rupert Neate: Ratings agencies suffer "conflict of interest", says former Moody's boss , The Guardian, August 22, 2011

- ↑ Kathleen L. Casey: In Search of Transparency, Accountability, and Competition: The Regulation of Credit Rating Agencies , sec.gov, February 6, 2009

- ↑ Rating agency: Millions fine for Moody's for upgraded ratings. Zeit Online , January 14, 2017, accessed January 14, 2017 .

- ↑ Ben Bernanke : Some Reflections on the Crises and the Policy Responses in: Robert M. Solow, Alan S. Blinder, Andrew W. Loh, Rethinking the Financial Crisis , Russell Sage Foundation, 2013, ISBN 978-1-61044-815- 4 , p. 4

- ^ The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report: Final Report of the National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in the United States , Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission , p. Xvii

- ↑ a b c d e f Mastering the financial crisis - strengthening growth forces. Annual report 2008/2009 of the Advisory Council on the assessment of macroeconomic development , item 174.

- ↑ Ben Bernanke, Some Reflections on the Crises and the Policy Responses in: Robert M. Solow, Alan S. Blinder, Andrew W. Loh, Rethinking the Financial Crisis , Russell Sage Foundation, 2013, ISBN 978-1-61044-815- 4 , p. 7

- ^ Paul Krugman , The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008 , W. W. Norton & Company, 2009, ISBN 978-0-393-33780-8 , pp. 170-172

- ↑ VIII. Final remarks: The difficult task of limiting damage (PDF) BIS, 78th Annual Report, June 30, 2008, pp. 159–174 (pp. 167 f.).

- ↑ a b c d Benedikt Fehr: The way to the crisis , Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , March 17, 2008.

- ↑ I. Introduction: The end of an untenable situation (PDF) BIS, 78th Annual Report, 30 June 2008, pp. 3–12 (pp. 8 f.).

- ^ Annual Report of the Council of Economic Advisers . United States Government, Washington DC. March 2009. Archived from the original on August 25, 2009. Retrieved on June 5, 2009., pp. 63 f.

- ↑ USA: Highest number of unemployed since 1967 tagesanzeiger.ch, January 29, 2009 (accessed October 18, 2010)

- ↑ Banking successes: Wells Fargo and Morgan Stanley also report high profits spiegel.de, October 21, 2009 (accessed October 18, 2010)

- ↑ Calculated according to information from the ameco database.

- ^ Paul Krugman : The New World Economic Crisis , Campus Verlag Frankfurt / New York 2009, ISBN 978-3-593-38933-2 , p. 175

- ^ A b Markus K. Brunnermeier: Deciphering the Liquidity and Credit Crunch. In: Journal of Economic Perspectivest , Vol. 23, No. 1, Winter 2009, pp. 77-100 ( PDF , p. 81).

- ^ A b Rainer Sommer: The Subprime Crisis in the United States , Federal Agency for Civic Education, January 20, 2012

- ↑ Hartmann-Wendels, Hellwig, Hüther, Jäger: How banking supervision works against the background of the financial crisis. Study by IdW Cologne, 2009. p. 28.

- ↑ Hartmann-Wendels, Hellwig, Hüther, Jäger: How banking supervision works against the background of the financial crisis . Study by IdW Cologne, 2009. p. 28.

- ^ Markus K. Brunnermeier: Deciphering the Liquidity and Credit Crunch . P. 79.

- ↑ On the shadow banking system, see also CESifo Group Munich: The EEAG Report on the European Community 2009, passim, ISSN 1865-4568 .

- ↑ Recently released data confirm productivity slowdown ahead of crisis , OECD, accessed May 14, 2009.

- ↑ According to Hans-Werner Sinn ( Kasinokapitalismus 2009, p. 226), the financial crisis encountered a long-lasting real economic downturn

- ^ The Economist , Jan. 25–31 . October 2008, ill. P. 82

- ↑ I. Introduction: The end of an untenable situation. BIS, 78th Annual Report, June 30, 2008, pp. 3–12 ( PDF , p. 3): “The turmoil broke out when a few funds with investments in structured finance products with younger US“ subprime ”mortgages were subject to suspend the redemption of units. "

- ↑ Gretchen Morgenson: Bear Stearns Says Battered Hedge Funds Are Worth Little. The New York Times , June 18, 2007.

- ^ Global Financial Stability Report. IMF, October 2008. ( PDF )

- ↑ Annual Report of the European Central Bank , p. 37 ( PDF ).

- ↑ IMF increases cost of financial crisis forecast to $ 11.9 trillion

- ↑ Schlaglichter der Wirtschaftsppolitik , BMWi, Monthly Report March 2009. Letter from the Scientific Advisory Board at the Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology to Federal Minister Michael Glos of January 23, 2009. ( PDF ( Memento of September 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ))

- ^ Floyd Norris: High & Low Finance; Market Shock: AAA Rating May Be Junk . New York Times, July 20, 2007.

- ↑ Mastering the financial crisis - strengthening growth forces , Expert Council for the Assessment of Macroeconomic Development (SVR), Annual Report 2008/2009, p. 120.

- ↑ a b c Annual Report 2011/2012, Second Chapter “I. World economy: The crisis is not over yet ” ( Memento from January 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive ), Council of Experts for the Assessment of Macroeconomic Development

- ^ Gary B. Gorton, The Subprime Panic , Yale ICF Working Paper No. 08-25, September 30, 2008, p. 1

- ↑ See Figure 7 in The Global Economy and Financial Crisis , IMF

- ^ Report on financial stability. June 2008 , Swiss National Bank (PDF; 894 kB), p. 12.

- ^ Report on financial stability. June 2008 , Swiss National Bank (PDF; 894 kB), pp. 12, 19.

- ↑ Dorothea Schäfer: Agenda for a new financial market architecture (PDF; 289 kB). In: DIW : weekly report, December 17, 2008.

- ↑ The entirety of the financially relevant EU decisions on the Greek and euro crises, i. H. in the days and nights from 7th to 9th May inclusive, is recognizable from various publicly accessible archives, e.g. B. from the archived news from Deutschlandfunk, see, for example, the second section in http://www.dradio.de/nachrichten/20100509080000 .

- ↑ Details: see e.g. B. EU approves multi-billion support for the euro , Spiegel Online of May 10, 2010, accessed on May 30, 2010.

- ↑ Press release January 13, 2010 of the Federal Statistical Office

- ↑ Eurostat decline in industrial production over 20% ( Memento from January 29, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 306 kB)

- ↑ University of Münster, Pfister, slide No. 5 ( memento from January 19, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 205 kB)

- ↑ a b Bernhard Graf and Stefan Schneider: "How threatening are the medium-term inflation risks?" In: Deutsche Bank Research April 30, 2009 (PDF; 301 kB)

- ↑ Page no longer available , search in web archives: Management report against the background of the financial crisis, p. 12 , PricewaterhouseCoopers (PDF)

- ↑ Guidance 2010 - Forecasts in Times of Crisis, p. 7 ( Memento of December 3, 2012 in the Internet Archive ), cometis AG (PDF; 1.0 MB)

- ↑ Welthungerhilfe food study ( Memento from December 11, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Oxfam Fact Sheet (PDF; 200 kB)

- ↑ UNCTAD (2009): The global economic crisis: systemic failures and multilateral remedies. Chapter III: Managing the financialization of commodity futures trading. P. 38

- ↑ John Baffes, Tassos Haniotis, Placing the 2006/08 Commodity Price Boom into Perspective, Policy Research Working Paper, The World Bank's Development Prospects Group, July 2010, p 20

- ↑ 1.02 billion people hungry. One sixth of humanity undernourished - more than ever before. , FAO, June 19, 2009.

- ↑ Graphics and text: Global financial and economic crisis 2008/2009 , from: Figures and facts: Globalization , Federal Agency for Civic Education / bpb

- ↑ Graphics and text: Development of cross-border trade in goods , from: Figures and facts: Globalization , Federal Agency for Civic Education / bpb

- ↑ Graphics and text: Shares and share trading , from: Facts and Figures: Globalization , Federal Agency for Civic Education / bpb

- ↑ Graphics and text: Public debt EU-28 and selected European countries , from: Figures and facts: Europe , www.bpb.de

- ↑ Graphics and text: Unemployment EU-28 and selected European countries , from: Facts and Figures: Europe , www.bpb.de

- ^ WZ Online: FMA board member Ettl warns of "geopolitical recession". Retrieved October 6, 2019 .

- ↑ Banks vying for dollar loans from the ECB. Financial Times Deutschland , September 11, 2008.

- ↑ “Fed urged the ECB to borrow dollars” , faz.net , January 25, 2013

- ↑ Joint action - central banks lend again billions . FAZ.net, September 18, 2008.

- ↑ a b Seven central banks jointly lower the key interest rate , NZZ Online, October 8, 2008 (accessed on May 1, 2009).

- ↑ Monetary policy decisions . ECB, November 6, 2008.

- ↑ Bank of England Reduces Bank Rate by 1.0 Percentage Points to 2.0% ( Memento from December 31, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), bankofengland.co.uk, December 4, 2008 (accessed May 1, 2009); Report from the Bank of England ( Memento of December 18, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) of November 6, 2008.

- ↑ US banking system receives help from the ECB - concerted action by central banks ensures US institutions access to liquidity in euros, yen, pounds and Swiss francs , Handelsblatt , April 7, 2009.

- ↑ "Big central banks supply banks with liquidity - fireworks on the stock exchanges - SNB also involved" , NZZ Online

- ↑ Bettina Schulz, Patrick Welter, Stefan Ruhkamp: "Debt crisis - central bank alliance triggers price rally." FAZOnline November 30, 2011

- ↑ Philip Plickert, Patrick Welter and Jürgen Dunsch: "Central banks permanently borrow foreign currency". faz.net of October 31, 2013

- ↑ BMF on the German bad bank solution ( Memento from June 15, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Bad bank variants (PDF; 38 kB)

- ^ Bundesbank press release April 19, 2010 - Maastricht debt level 2009 ( Memento of April 23, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Press release of the Bundestag from May 11, 2010 ( Memento from May 17, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Deutsche Bundesbank: Financial Stability Report 2009, Chart 1.1.4.

- ↑ Tim Oliver Berg, Kai Carstensen: A return to the old role is required soon! , in: Wirtschaftsdienst , Vol. 92 (2012), no . 2, Zeit talk, pp. 79–94, doi: 10.1007 / s10273-012-1332-0 .

- ↑ See Bernhard Ecker "10 Years Lehman Bankruptcy: Life After the Panic Attack" in Der Trend from August 10, 2018.

- ↑ Press release of the EU Commission from May 27, 2010

- ↑ Press release of the Deutsche Bundesbank April 13, 2011 ( Memento of April 16, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Joaquín Almunia Vice President of the European Commission responsible for Competition Policy Restructuring EU banks: The role of State aid control CEPS Lunchtime Meeting Brussels , February 24, 2012

- ↑ Olaf Storbeck, “How Taxpayers Feed the Banks” , Handelsblatt June 14, 2012

- ^ "Taxpayers supported the banking sector with 1.6 trillion euros" , Süddeutsche Zeitung , December 21, 2012

- ↑ Banking Crisis Management ( Memento from May 13, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), European Commission , around June 2012

- ↑ New crisis management measures to avoid future bank bailouts , EU press release, June 6, 2012

- ↑ MEPs torpedo bank controls ( Memento from January 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), press release by H.-P. Martin , Independent MEP, October 22, 2012

- ↑ final declaration in full ; Publication of the final declaration on the website of the Federal Government of Germany ( Memento of February 7, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ “That was decided by the G20 summit” , Handelsblatt

- ↑ On the communiqués of the G20 group ( Memento of April 10, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ G20 - top ten outcomes. Archived from the original on January 25, 2010 ; Retrieved December 19, 2011 .

- ↑ Andreas Oldag: G-20 Summit - The Trillion Trick , Süddeutsche Zeitung, April 4, 2009, accessed on December 19, 2011

- ↑ Carsten Volkery: G-20 summit in London: industrialized countries celebrate the trillion compromise , Spiegel online, April 2, 2009, accessed on December 19, 2011

- ↑ Comparison of the gross domestic products of 2009 and 2010 , imf.org, accessed on December 19, 2011

- ^ Final document of the G20 summit in Pittsburgh ( Memento from August 15, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Final document of the G20 summit in Toronto ( Memento from September 24, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The old game of hide and seek , by Günter Heismann, Die Zeit, March 14, 2013

- ↑ a b Press release: Structural reform of the banking sector in the EU , European Commission, January 29, 2014

- ↑ a b Separate banks: Separated to be united , Nina Hoppe, July 30, 2015

- ↑ EU parliamentary committee missed agreement , Handelsblatt, May 26, 2015

- ^ Report from Brussels , Representation of the State of Hesse to the European Union, 11/2015 of June 5, 2015

- ↑ separating banking idea on the brink of , by Elisa Simantke , Der Tagesspiegel, May 5, 2015

- ↑ EU finance ministers agree on separate banking rules , Reuters, June 19, 2015

- ^ Agreement on separate banking rules , by René Höltschi, NZZ, June 19, 2015

- ↑ a b Structural reform in the EU banking sector: making credit institutions more resilient , European Council, October 13, 2015

- ↑ It is wrong to focus on the ban on proprietary trading by banks , SAFE - Sustainable Architecture for Finance in Europe, February 11, 2016

- ↑ Separate banks law is about to expire in the EU ( Memento from February 10, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Wirtschaftsblatt, February 9, 2016

- ↑ EU finance ministers agree on separate banking rules , OnVista, March 13, 2016