Volunteers of the People's Police

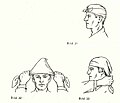

Volunteer of the People's Police (FH) was a voluntary activity by laypeople for the German People's Police (DVP) between 1952 and 1990 . You worked on the legal basis of the German Democratic Republic in the police service in the various areas of the DVP . The helpers only wore a red armband (see illustration) on their left upper arm to identify them . There was no uniform, in some cases isolated pieces of uniform without national emblems, epaulettes, etc. were used.

The areas of application in internal security were varied and ranged among others. a. from the control of public life and border installations to road safety . The priorities changed, however, according to “current political requirements” ( collectivisation of agriculture , building of the wall and compliance with plans by the companies, etc.) or regionally from district to district in the GDR . Several helpers in the security police saw themselves as counterparts to the members of the voluntary operational Komsomol brigades of the Soviet militia and accordingly demanded in December 1959 z. B. by the responsible minister ( Ministry of the Interior (MdI) ) an increase in their competencies, but this was rejected. With the note that the helpers should work exclusively under the personal guidance of a people's police officer. During this time the goal of their use was z. B. "Educational influence in residential areas , in companies and collectives ". Her area of responsibility extended to the uncovering of criminal offenses , violations of legal interests as well as their causes and favorable conditions, the prosecution of which, among other agencies, was mostly guaranteed by the People's Police.

It was founded on September 25, 1952, and was dissolved on September 30, 1990.

Historical development

Establishment and approval

A preliminary stage of the voluntary helpers of the People's Police was the honorary service in the German People's Police , which many FDJ members joined in 1952. In October 1952 the Section Authorized Representatives (ABV) were introduced. The GDR leadership was able to fall back on Soviet experience in developing the fields of activity of the later ABV.

On September 25, 1952, the GDR's Council of Ministers approved volunteers for the People's Police and their legal context was outlined in the order: People who had reached the age of 17 could join groups of volunteers to support the People's Police organized by the People's Police “To be recorded.

The ordinance initially contained little concrete information on structure, subordination and tasks, which initially encouraged a kind of "wild growth". The ordinance of September 1952 was in any case a reaction to the establishment of volunteer brigades in the summer of that year, especially in the former state of Thuringia . Only later regulations corrected this.

Establishment and consolidation in the state apparatus

With this ordinance, the voluntary helpers of the People's Police achieved their legality and at the same time their powers before the law. With order no. 152/52 from the head of the KVP of December 10, 1952, the structure and organization of the ABV was established. From then on, he was the link between the People's Police, including through the people's voluntary helpers to the population. In the weeks and months that followed, the ABV helper system was refined and established. Both ABV and the voluntary helpers of the People's Police saw themselves in their work as operational preventive, that is, directed towards the prevention of criminal offenses, misconduct and administrative offenses as well as the averting of dangers and disturbances.

In larger VEBs , the voluntary helpers for industrial security (A) also emerged . Just a few months after the founding of the ABV and the voluntary helpers of the People's Police at the end of 1952, the main administration of the People's Police came to the conclusion that the ABV helper system should be further consolidated and expanded. The establishment of the ABV and its helpers was completed by the end of 1952.

On March 16, 1964, a second ordinance was issued, in the course of which the activities, powers and admission requirements of the volunteers were more clearly defined. The new ordinance did not only affect the volunteers of the People's Police, but also the volunteers of the border troops of the NVA , who played a subordinate role in this ordinance.

On August 1, 1965, a directive was issued by the Minister of the Interior and Chief of the German People's Police on the work of the voluntary helpers of the German People's Police.

On April 1, 1982, with effect from May 1, 1982, the Council of Ministers of the GDR issued the third and last ordinance in which the volunteers of the People's Police and the border troops that had previously been treated together were again treated separately. While the voluntary helpers of the border troops were included in the law on the state border of the German Democratic Republic , also with effect from May 1, 1982, the ordinance on the voluntary helpers of the German People's Police now expressly determined a complete catalog of powers as well as the concrete employment requirements and mediation principles. According to the opening words, all those who, through their willingness and active participation in ensuring public order and security, contributed to "ensuring the reliable protection of workers and peasants" were now considered to be voluntary helpers of the German People's Police. By definition, these were citizens of the GDR who actively supported the German People's Police on a voluntary basis and performed tasks on the basis of the decree issued. Their activity was regarded as a form of “conscious and active participation of the citizens in order to exercise their basic rights and obligations in protecting the socialist society of the GDR”.

Role of state security

The results of previous scientific research show that the aim of creating volunteers was by no means just to reinforce the staff for patrol and post service or at major events and to influence the citizens to ensure compliance with the law. From the beginning it was also about discreet spying on where the “workers and peasants” could not gain access until now. Which caused the work of some of the volunteers to conflict with their actual mission.

Statements by former people's police in the Dresden district , who were superiors and trainers working directly with volunteers, also allow the conclusion that the State Security specifically placed volunteers, probably also with toleration or approval by the people's police. Thanks to their help, the GDR Ministry for State Security was able to extend its surveillance network to these groups of people in order to be able to tailor and pursue conspicuous "subjects", also and above all in their own ranks. Specific numbers of volunteers who worked as IM are not to be provided. As a point of reference, one can use the "exposure quota" of members of the People's Police of almost 40% who were considered to be "IM-contaminated" due to such state security activities and who had to retire from the police force in the course of the IM review after the fall of the Wall.

The work of the volunteers of the People's Police was limited, based on the experience of June 17, 1953 , to a purely informative patrol activity . With the beginning of the collapse of the GDR state system, the original assignments of volunteers were cut more and more. Their tasks were taken over by state-loyal and straightforward organs such as B. the fighting groups of the working class . So it was not surprising that the volunteers, initially treated as persons of respect, were now deputized for the hated GDR regime, made contemptuous or ridiculed for their work and their work.

Turning time and dissolution

At the latest at the time of the change in the GDR , the majority of the preventive measures were no longer taken seriously by the citizens, requests were boycotted or simply ignored. In the area of the Dresden district, the volunteers of the People's Police were in fact no longer existent at the end of December 1989. The background was that the companies no longer saw any incentive in releasing the volunteers from their work. Far-reaching consequences and unprecedented economic problems were faced. The system of the section authorized representative then collapsed completely in this district by around mid-1990, so that the volunteers ceased to exist by this point at the latest. The dissolution of both groups of volunteers, both that of the People's Police and that of the GDR border troops, happened almost in parallel, but not identically. For example, on September 13, 1990, the GDR Council of Ministers issued the "Law on the Duties and Powers of the Police" with effect from October 1, 1990, which was based on the basic principles of the Federal Republic of Germany as laid down in the Unification Treaty of August 31, 1990 was. The law created in this way was an interim solution and should be valid until the respective country-specific police laws come into force. With the coming into force of the law on October 1st, the previous "Ordinance on the Voluntary Helpers of the German People's Police" of April 1st, 1982 automatically expired on September 30th, 1990 at midnight, which meant that the volunteers were in fact without a legal basis on October 1, 1990 (from 0:00:01 a.m.). Its official dissolution can therefore be dated September 30, 1990.

Short chronicle

- September 25, 1952: The regulation of the Council of Ministers of the GDR on the formation of groups of volunteers to support the People's Police is announced. The first volunteers come from the working class and are supposed to support the work of the People's Police.

- December 10, 1952: On the orders of the chief of the German People's Police, Karl Maron , the construction of the system of the authorized officer begins. These should win volunteers to support their work.

- January 1954: The 17th meeting of the Central Committee of the SED brings resolutions on the radical socialist restructuring of agriculture. As a result, the section authorized representative and his voluntary helpers in the rural communities of the GDR have increased tasks.

- December 1955: First large central ABV conference. The experience gained so far with the volunteers should be quickly generalized, especially through better training.

- August 13, 1961: Volunteers from the People's Police and the German Border Police are particularly involved in cordoning off the roads and railways in the course of the construction of the Wall .

- May 24, 1962: Decree of the Council of State of the GDR on the administration of justice. Groups of helpers then checked their tasks.

- September 1967: Friedrich Dickel publicly pays tribute to the work of the now more than 100,000 volunteers in Berlin. At the same time, more and more recent initiatives come from so-called “advanced helper collectives”.

- February 17, 1969: At the same time the Council of Ministers of the GDR decides to further increase road safety and the associated responsibility of the FH in this area.

- October 1969: Hundreds of volunteers in the state capital are entrusted with the security for the 20th anniversary of the GDR.

- June 29, 1970: Ceremonial event in Friedrichstadt-Palast as a result of which the Council of Ministers of the GDR and the Central Committee of the SED honor the services of the People's Police and their helpers.

- July 1970: On the 25th anniversary of the People's Police, the state leadership of the SED proclaims the results of the successes of the volunteers.

- December 17, 1971: Regulation of transit traffic through massive reinforcement of the volunteers (in association with the VP) on the transit roads .

- June 15, 1972: The Minister for National Defense of the GDR issues the order on order in the border areas and territorial waters of the German Democratic Republic (border order)

- September 25, 1972: For its 20th anniversary, “deserved helper collectives” are honored by the Minister of the Interior, Friedrich Dickel.

- July 28 - August 5, 1973: The 10th World Festival takes place in East Berlin. Volunteers are involved in the process organization.

- April 1, 1982: The new ordinance on the voluntary helpers of the German People's Police comes into force.

- September 13, 1990: Enactment of the law on the tasks and powers of the police with effect from October 1, 1990. The volunteers are no longer mentioned therein.

- September 30, 1990: Official dissolution of the Volunteers of the People's Police.

Classification and structuring

The division and structuring took place depending on the situation and mostly adapted to local conditions. However, they were an integral part of the organization of the German People's Police. In particular in the area of the section authorized representative, where they represented an important role in "ensuring security and order". With the use of volunteers, the People's Police were able to compensate for their own staff shortages.

The fields of activity differ as follows:

- Volunteers

- the protection police

- in their districts

- for authorized officers (ABV) of the police force

- of operational security

- the traffic police

- the criminal investigation department

- the transport or railway police

- the water police

- the dike weir

- the border police (1958–1964 on the basis of separate legal bases)

- of the border troops (1964 until the final separation in 1982 - on the basis of common legal bases)

- the protection police

The volunteer helpers of the dyke defense, mainly deployed in the coastal area of the Baltic Sea or in the Brandenburg Oderbruch , had the task of checking the condition of dykes and dunes together with dyke protection patrols or the fire brigade .

The members of the transport police (Trapo), to which the railway police belonged, wore dark blue uniforms. In their ranks also served a section representative, who was recognizable by a shield-shaped blue sleeve badge, on the upper edge of which was slightly curved in white lettering section representative . He, as well as the Reichsbahn in general, were subordinate to the transport police as reserves or to support all kinds of volunteers. Since their tasks in the broadest sense are identical to those of the Volunteers of the People's Police, their areas of responsibility also relate to those of the Transport Police. The Trapo volunteers did not wear a blue armband, but the well-known red one.

| Possible command structures for the volunteers in action | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model structure of the volunteers of the People's Police with the ABV | Model structure of the volunteers of the People's Police in the context of the deployment with the People's Police | Sample of a command structure for the volunteers in the transport police with the ABV | Internal model structure of the volunteers of the People's Police |

The structural organizational structure of the volunteers was in principle very simple. At the head of a group of voluntary helpers was generally the authorized officer who , in contrast to his voluntary helpers, was a police officer of the German People's Police and was accordingly allowed to wear a uniform. Each section plenipotentiary was assigned a certain number of volunteers, the number of which could vary from region to region, even from section to section. More helpers were deployed in new housing estates in large cities than in small village communities in rural areas.

The internal structuring of the volunteers of the People's Police among themselves largely corresponded to that of the National People's Army, i.e. in a ratio of 1: 3: 27. There were three group leaders for one platoon leader. Nine volunteers each belonged to a group. However, this size allocation or internal structuring could only be adhered to in theory. In practice it was subject to constant fluctuations. Section officers and voluntary helpers were entrusted with the patrol duty in their main task , whereby most of the incidents in the responsible police station were reported by the helpers to their ABV. He informed the People's Police, if this had not already been done by the volunteers. However, the ABV was not always the superior in the narrower sense, especially when the volunteers were deployed as escort or auxiliary staff in the People's Police . A member of the People's Police was able to give instructions to a volunteer without informing the responsible ABV; usually in the case of "imminent dangers". Of course, the volunteer also had the duty to notify the nearest police station of the People's Police, regardless of their subordination, about incidents. The case was different when the voluntary helpers of the People's Police were on duty together with members of the VP, as in a manhunt or general traffic control. In this case the superior was always the superior of the People's Police.

Special use in the criminal police

The service of volunteers in the People's Police in the Criminal Police Department was classified by the Ministry of the Interior. Their use was therefore also subject to the addition of a confidential official matter . The 1st implementation instruction issued for this purpose of July 21, 1986 primarily contains the assignment of tasks to the volunteers as well as their operational activities, in particular during searches. Accordingly, volunteers from the People's Police could also be called in to support the Criminal Police in solving these tasks by the People's Police and to prevent and combat such crime. The head of the criminal police or his deputy were responsible for the necessary political and technical training and qualification as well as for the actual work of the volunteers with the police. They were also responsible for placing individual orders, checking the results and maintaining proof of work for such activities, as well as providing annual instruction. The criminologists responsible for the assignment gave the volunteers their orders and instructions, settled the work results and made an annual assessment of these results. It is noteworthy that this contract placement had to be done orally only . They also initiated a personal development report for the volunteer. The specific tasks of the volunteers included:

- Prevention, detection and investigation of criminal offenses and other legal violations in companies, cooperatives, residential areas, etc.

- Participation in the detection and clarification of criminal offenses, in particular the determination and transmission of information about possible suspects

- Detection of red-handed perpetrators

- Independent implementation of initial measures at crime and incident sites such as first aid services, witness statements and information gathering

- Support function of managers, boards of directors of cooperatives and other managers in eliminating the causes and conditions for criminal offenses

- Implementation of state control measures i. S. d. Section 48 of the GDR Criminal Code

- Control of compliance with conditions such as residence and contact prohibitions

- Influence on control persons through educational measures in the sense of reintegration

- Establishing facts about the behavior of recidivists through surveillance

- Participation in house searches as part of the People's Police of people with control measures

- Identification of “anti-social elements” who do not do regular work and who are at risk from criminal acts

- Organization and implementation of search work

- Help with the distribution of flyers, offprints and other wanted materials

- independent long-term search activity as part of their professional activity

- Review of information and information from the population on wanted matters and their follow-up

- Checking and monitoring of wanted-relevant places within the framework of the People's Police (apartments, restaurants, etc.)

- Checks for wanted art and cultural goods such as at flea markets, trade fairs and the like

In such cases, the selected volunteers operated independently or in cooperation with members of the People's Police. A group deployment of several helpers could, however, also come into consideration with appropriate search control, such as B. at larger festive events. As a rule, they were selected on the basis of their professional and / or social activity as well as their leisure time behavior, which served the purpose of the search and thus enabled them to actively participate in crime prevention and its fight.

Numerical development

An exact listing of the volunteers based on their areas of activity is not possible. Previous sources speak of a total of 177,500 volunteers, which, however, should have existed from the establishment to its dissolution. Around 2500 of them were volunteer helpers with the border troops. Others put a number of 4000 here. The first number has, however, been misinterpreted. These 177,500 helpers are not the total number, but the number of volunteer helpers of the People's Police in relation to the year 1988. However, the Ministry of the Interior speaks of around 177,000 people in this year in question. In an interview in April 1987, Helmut Ferner , Head of the Main Police Department, spoke of 177,000 volunteers.

The first numerical recording of volunteers of the People's Police dates back to 1959, when the Ministry of the Interior of the GDR named around 10,000 volunteers. On the 20th anniversary of the founding of the Volunteers of the People's Police, on September 25, 1972, the People's Police had around 127,000 men and women as volunteers of the People's Police. Of these, about 88 percent were assigned to support the section authorized representative and more than 7 percent were subordinate to the traffic police. Almost every second of them, around 67,000 volunteers, were even given special powers. Looking at these figures, it becomes clear that the annual number of volunteer helpers of the People's Police, apart from the early years from the 1970s, has been constant at around 170,000 and 175,000 helpers of the People's Police. Several thousand helpers from the border troops have to be added to this. As early as 1968, 1.9 million citizens of the GDR were active in various commissions for order and security. This affected not only the helpers of the People's Police and border troops, but also countless voluntary helpers in the fire brigades, the operational security , as well as the air protection helpers of the OdR . A breakdown of the voluntary helpers into male and female personal assignments was not made even in GDR times. The majority, however, were male.

Rights and duties of the helpers of the People's Police

All voluntary helpers carried out their work to ensure public order and security under the leadership of the German People's Police within the framework of the powers assigned to them. However, they usually carried out the tasks assigned to them independently or in cooperation with VP members, for example during traffic checks or searches. In addition, they had to maintain strict confidentiality towards unauthorized persons about all reports and facts that came to their attention during the service. A distinction is to be made between the special powers that go beyond the extent of the delegated powers . These could only be transferred by a head of the People's Police District Office. In this context, the volunteers had the right and the duty :

| General rights and obligations | Special rights and obligations |

|---|---|

|

|

In addition, the Minister of the Interior and Chief of the People's Police could issue further far-reaching powers , which, depending on the type and severity of the situation, could go far beyond the powers of a member of the People's Police. But even so, the powers of the VP's volunteers have always been expanded. In the course of a further required increase in road safety and due to the 2nd implementing ordinance of the StVO from August 1, 1965, they were given far-reaching transport policy tasks. For this purpose, they were grouped into so-called “specialist groups” according to their interests, trained and brought to the

- Traffic monitoring

- Traffic education

- Traffic accident record as well as

- voluntary auxiliary motor vehicle experts

increasingly used.

Exceeding authority and punishment

As with the members of the People's Police, there were experienced helpers who appeared through competent and confident demeanor. On the other hand, superiors also registered excessive "diligence" and overstepping of competencies. While the people's police were subject to the disciplinary system of the people's police, offenses committed by volunteers could not be prosecuted and punished through this regulation. In the event of a proceeding, the volunteer was either completely excluded as a helper or had to expect his powers to be curtailed, depending on the severity of the offense.

Operational catalog of measures (extract)

As is a matter of course with today's police measures, the helper had to adhere to legal restrictions in the performance of his service when exercising his powers. So were all measures taken only perform as long as this appeared to respond to threats or to eliminate interference in the interest of restoring public order and security offered. The resulting catalog of measures for the voluntary helpers of the People's Police primarily contains the behavior and procedure of the helper when an event is to be expected or has occurred. The blue memo booklet was the helper's little helper, could be conveniently stowed in the trouser pocket or deployment pocket and served in the event of an emergency not to exceed the assigned competencies and spheres of activity or to fill them in completely depending on the situation. Overzealous volunteers learned this catalog by heart. The very extensive catalog contains 89 situations, arranged according to alphabetically sorted keywords, from the ash deposit to the referral of suspicious persons to the TP . The key points were supplemented with a description of the most important measures. It should be pointed out that the Volunteer of the People's Police was neither allowed to accept nor receive reports from citizens. Otherwise, the helper had to refer the injured person immediately to the authorized officer who had this competence or to the nearest office of the People's Police. Subsequently, depending on the circumstances, crime scene security and / or security or removal of the danger point had to be carried out. By securing the scene of the crime , the volunteer understood the securing of the scene of the incident as the most important starting point for further investigations by the People's Police. It was therefore all the more important that the helper knew the basic principles of a criminal investigation. He was therefore obliged not to touch or change anything at the scene of the crime, unless other regulations precluded this. This was the case in cases such as the covering of inflammatory slogans or the removal of inflammatory pamphlets, but also in the outpatient treatment of any injured persons by the voluntary helper or the arriving rescue service. In such a case, however, the outlines of the injured person were marked with chalk so that the criminal police could later reconstruct the case. If the crime scene was secured, for example if unauthorized persons were prevented, the helper immediately reported to the TP. Witness statements had to be recorded until they arrived and any agreement between them had to be prevented until they were questioned by a police officer. Traces (blood stains etc.) that could be smeared due to the weather had to be protected. In addition, there was a strict ban on smoking at the crime scene (even outside of rooms). However, the helper was also entitled to take measures to arrest the perpetrator, such as hiring a third person to prosecute him. In rare cases, the pursuit of the fugitive after a theft and the like.

The input had to be distinguished from the ad admission or acceptance . In this case, the helper was obliged on all his patrols to receive written or oral suggestions, information, concerns and complaints with which the citizens turned to him (on behalf of the state parliament). Public safety and order problems were referred to the People's Police. The helper could also be commissioned with the processing by the section authorized representative. Since the individual listing of all measures would go beyond the scope, the most important measures are discussed here. In detail the following were:

Harassment and abuse

Harassment in the GDR included any improper behavior by people towards others in the form of mobbing, fights, swear words and the like. Insults , on the other hand, were gross disregard for personal dignity through infamous insults, assaults and immoral acts. In the case of both types, the volunteer first pointed out to the People's Police that the insult or the harassment had to be avoided. At the request of the injured party, the personal details were then exchanged, with the volunteer taking on the role of the exchange person. He then had to instruct the parties to turn to the Arbitration and Conflict Commission in the event of a legal dispute , which in the GDR was the first point of contact for such offenses before the courts. If, however, the volunteer himself was harassed or insulted in the course of his intervention, the personal details of the perpetrator were recorded and a corresponding report was initiated to the People's Police. If the volunteer had a bad day, such facts could end with the transfer to the TP.

Search operations

During search operations , in which volunteers from the People's Police as well as from the border troops could be involved, the helpers had an important examination task. But first, this manhunt operations differed in persons investigation and subject-search . In the case of searches for people, the volunteers were sent to reinforce the people's police officers who had already been deployed to heavily frequented locations such as train stations , airfields or traffic junctions , in order to scrutinize those people who matched the search grid. The “target persons” had to identify themselves and were compared with the grid matches. If the volunteer came to the conclusion that the suspect needed a more detailed examination, he handed him over to a member of the People's Police or was able to take the suspect to the nearest office himself. In the case of property searches, such as the theft of passenger cars , the volunteer followed the same pattern. For example, he subjected all vehicle owners of the Wartburg 353 type with the desired grid color such as red or white to a traffic control at a selected point, which could either be carried out by the People's Police or, in smaller communities, by the helper himself A manhunt, like a bicycle theft, was followed by the volunteer as part of his foot patrol.

House book control

The control of house books , the number of which amounted to around two million in 1988, was initially the responsibility of the house book officer of the apartment building concerned. He had to hand over the house book at any time upon request to the authorized officer and voluntary helpers of the People's Police, but only to those with special extended authority for inspection and control. If the house book had to be checked immediately for urgent reasons, or if it was to be carried out as part of a routine examination, the Volunteer People's Police checked the house book to see whether all tenants of the house had been properly entered and whether the residential units were a main or secondary residence respective tenant acted. In addition, the determination of the people present in the house was of the greatest importance, since in the event of a possible family visit that lasted more than three days, these people also had to be recorded in the house book with the note `` Visiting stay '' . The personal details who came from West Germany to visit the East were carefully checked . The house book officer also provided corresponding notes with the reference D or BRD . In this context, the volunteer checked whether more than 24 hours had elapsed between the time of entry of the visit and the entry. The time of entry was to be found out from the responsible People's Police Station or the authorized officer if the house book officer had failed to ask the West visitor about the time of their entry. Other checkpoints when checking the house book concerned name changes in the event of marriage, moved groups of people and the handwritten certification of the tenants for the correctness of their information.

Anti-state agitation and defamation of the state

If the helper encountered anti-subversive agitation during his stripes , he first had to know the definition of this term. According to this, anti-subversive agitation was committed by anyone who, with the aim of damaging or inciting against the socialist state or society, threatens to commit crimes against the state or calls for resistance to the socialist state or society of the GDR Glorifies fascism or militarism, disseminates or installs inflammatory pamphlets, anti-subversive slogans or symbols and the like, discriminates against representatives or other citizens of the GDR or the activities of state or social organs and institutions.

In the event of verbal agitation, the helper had to determine the perpetrator's personal details and, if he refused, bring him or her to the People's Police immediately, or arrest them temporarily if necessary. Any witnesses could be heard and their statements were precisely recorded. The procedure for written agitation looked different. Discarded inflammatory pamphlets (leaflets) were to be collected immediately when found. The time and location were then recorded and immediately communicated to the TP. If the helper was given a hate speech by a citizen because he had found one on the street, etc., he recorded his personal details as well as the location and time and also passed this information on to the TP immediately. In the case of inflammatory slogans, such as wall paintings, the location had to be secured and the slogan not to be touched or removed. In this case, the helper was obliged to cover the hate speech with tarpaulins or blankets as far as possible without obscuring any traces and thus withdrawing it from further view. Here, too, an immediate witness investigation and notification to the VP took place. The situation of the volunteer was particularly precarious on June 17, 1953 , the popular uprising in the GDR, whereupon all VP helpers had to be mobilized inconspicuously in future events and trained and instructed for future missions. The last such events took place in the course of the turmoil in 1989/1990, when countless reports were made to the VP by volunteers of the VP.

Defamation of the state in the GDR was committed by anyone who publicly despised the state order or state organs, institutions or social organizations or their activities or measures, or who defamed a citizen of the GDR, including insulting voluntary helpers because of their affiliation makes statements of a fascist or militarist character to a state or social organ or social organization that are despised or slandered. In practice, this meant that if the volunteer was insulted or denigrated by a person because of his voluntary work, that person could possibly be prosecuted and convicted of defamation of the state. Otherwise, the helper proceeded the same as with the anti-state agitation.

Identity determinations

The identity determination , also briefly called Personal finding was one of the most frequently used rights transferred the volunteer helpers. Without this right, proper work would not have been possible. The identification of the person meant the inspection of the identity card or equivalent documents. This included all types of service books and ID cards, party books, military passports or diplomatic passports, but also the temporary identity card and driver's license. The control of the personal documents of citizens of West Berlin or the Federal Republic was tricky. As a rule, these were not allowed to be checked by the volunteer, but only after a corresponding official briefing by the TP, which was then also noted on the helper's ID. On the other hand, the recording of personal data included writing down personal data. However, the personal data recording was also subject to limits, so it could not be used by the helper at will. It was only permitted when performing the assigned tasks such as the identification of witnesses, deliveries, arrests, searches and vehicle controls as part of the traffic police . The so-called exchange of personal data in the GDR was a civil law claim of every citizen against another citizen of the GDR, if he could credibly justify it. In this case, the volunteer was obliged as an intermediary to support the exchange of these personal details. This has been the case with all types of harassment, insults, trespassing, assault and defamation. Specifically, this means that if the helper was called to such a case, he inspected the suspect's personal details and passed this information on to the person making the request. Reference should be made to the possibility of clarification of the dispute by a social court or a lawsuit. In addition, the identity card of the GDR had to be carried with you at all times and was to be given to the People's Police, the helper or other authorized persons upon request. The data was checked based on the validity of the ID, entries and changes as well as the comparison of the photo with the person. Refusals to show them usually lead to transfer to the TP. In the case of deficiencies or inconsistencies, however, only a notification was made to the VP office, which then took over the further initiation. If the citizen had lost his ID and was able to credibly assure the volunteer of this (e.g. after a robbery), the helper referred the injured party to the VP registration office or the ABV.

Motor vehicle inspection

The wide range of tasks of the volunteer at the vehicle control , which mainly took place in the context of the assignments with the regular traffic police, related not only to the general traffic controls, but also to the traffic monitoring in the context of the VP or self-employment as well as the accident recording. Even stopping motor vehicles was only permitted to helpers who were specifically authorized to do so. In urgent cases that required rapid intervention, such as gross violations of legal obligations in road traffic or serious technical defects, the helper could give the other driver the signal to stop manually or with a signal stick from his moving vehicle. In any case, the helper then checked the driving license and the vehicle documents of the sinner and was able to instruct him in the case of minor offenses, but also request the correction of a technical defect. If that was not possible on site, the helper wrote a so-called notification of defects. In this, on the one hand, the vehicle driver was set a removal deadline and, on the other hand, the obligation to prove the corrected defect in a nearby office of the VP. Incidentally, improper loads had to be arranged or newly secured on site by the vehicle driver. Trailers requiring registration that were not properly registered or whose papers could not be produced during the inspection had to be parked in order to prevent further travel and to call in the VP. Another point during the vehicle inspection was the lighting, which could be checked for functionality, and an immediate remedy of defects could be ordered here too. If the volunteer noticed an alcohol flag from the driver in the course of his traffic control or if it appeared to be drunk at the wheel , every measure had to be taken to prevent the driver from starting again. This was followed by routine identification of personal details, with the identity card and vehicle documents being provisionally confiscated. If the helper was in possession of a breath alcohol test tube , he could use this on the driver of the vehicle before the TP arrived, who had to be informed in the meantime. The helper's sphere of activity when involved in a traffic accident was dependent on the severity of the accident. A distinction was made between a road traffic accident with minor consequences without personal injury and only minor property damage of up to 300 marks , and a road traffic accident with greater consequences with personal injury and property damage of more than 300 marks. In the first case, the volunteer arranged for any traffic disruptions that had already occurred to be removed immediately and for the accident site to be secured, then recorded the personal details of the person involved and notified the TP. In the case of accidents with personal injury, the same procedure was to be used, but based on the principle of priority of assistance.

Self-defense

The legal right to take personal action against illegal attacks and to prevent threatening damage through defensive actions through this attack was not only incumbent on the volunteer in appropriate emergency situations, but was available to every citizen of the GDR. If the helper encountered such a situation in the course of his patrol, he was obliged to assist the persons in distress in a suitable manner and to inform the TP promptly or to have them informed. If the volunteer acted in self-defense, the German People's Police were informed immediately after the self-defense, stating the personal details of the attacker and the facts of the matter. The attacker himself was temporarily arrested by the helper and then taken to the TP. Incidentally, the volunteer could not be prosecuted if the self-defense measure was exceeded ( resulting in death) if the agent was put into a justified high degree of excitement and for this reason also went beyond the limits of self-defense.

Administrative offenses and criminal offenses

An administrative offense in the GDR was anyone who culpably had committed a violation of the law, which expressed a lack of discipline and made it difficult for the state to function properly and disrupted the development of socialist community life. The volunteer could not pursue administrative offenses , i. H. enforce, but prevent improper actions and instruct the citizen in the case of minor misdemeanors. In the event of significant disruptions, a report was made to the VP, stating the personal details and the circumstances. According to GDR law, criminal offenses were all culpably committed acts that were socially unlawful or dangerous to society (action or omission), which according to the law gave rise to criminal liability as an offense or crime. If the volunteer witnessed or was even suspected of a crime, he was also authorized to temporarily arrest the person or suspect, to question any witnesses, to secure the scene of the crime and subsequently to restore public safety and order or to maintain.

Property damage and theft

The property damage report was one of the few operational measures that the volunteer inevitably had to deal with every day during his patrol. Such cases were a long-running hit, especially in large cities such as Berlin , Karl-Marx-Stadt , Leipzig or Dresden. Damage to property in the GDR included not only willful damage to property, which also included the damage to or rendering unusable of socialist property, but also damage to public announcements by the state organs. Only the announcements of the city council and the like are mentioned here. This also included:

- Damage to benches (park benches, etc.)

- Damage to enclosures (fences, walls)

- Demolishing public flower beds and shrubs

- Smearing walls and waiting rooms

- Breaking window panes

- Overturning waste bins and ash bins and that

- Entering plantings such as flower beds

If the helper witnessed such damage, he had to stop the violation of legal interests immediately and record his or her personal details. Depending on the severity of the injury, there was either a warning and instruction or the transfer to the next VP police station. In the case of the theft , the procedure was similar to the damage to property, only there was no more instruction, but the handover to a VP member and the seizure of the stolen goods. If the volunteer was only informed of a theft, he referred the injured party to the nearest VP office or the ABV, as he was not authorized to report it. In addition, the helper was authorized to pursue fugitive thieves in the course of his service and to secure any traces at the crime scene.

Fights / assaults / bodily harm

It was not uncommon for the TP's volunteer to be called to night brawls and acts of violence in public, the tactical approach of which required the helper to act promptly but also wisely. Brawls and assaults included assault , assault against citizens because of their state or social activity, hooliganism, drunkenness in public and disturbance of socialist coexistence. As a first measure, the volunteer asked those involved to refrain from further such actions and primarily to provide first aid to any injured persons. If the brawl could not be stopped by the intervention of the helper, even with the support of other neutral persons, the People's Police had to be notified, if not already done. If the helper succeeded in ending the assault, routine work such as taking down personal details and, if necessary, transferring them to the TP would take place. Brawls or assaults involving bodily harm required an identical approach.

Prevention of junk and dirty products

The actual secondary topic, however, listed in the list of measures of the helpers, is the control of so-called dirt and junk products . Their distribution and importation was prohibited in the GDR. A large part of the category of trash and dirty products was related to literary works that were suitable for conveying tendencies towards racial and ethnic hatred , cruelty , contempt for human beings , violence , murder and other crimes in children and young people . This also included works that could contribute to sexual aberrations and magazines of pornography . In contrast to the other preventive measures, the volunteer had to collect this immediately when it was discovered, i.e. not first secure the crime scene, but immediately determine the owner's personal details. In this research, it was important that the volunteer determined the origin of the trash or dirty product. He then handed everything over to the People's Police with a written report. Usually those were products of traveling from the socialist countries like Czechoslovakia , Hungary and Romania introduced or through the transit traffic of the GDR from West Germany and West Berlin. For a short time, the magazine Magazin was one of the dirty products, since underage schoolchildren were able to access erotic literature in the course of their waste collection . The subsequent dissemination of the nude photos among classmates at a polytechnic high school in Kamenz led to a public reprimand among several lower school students , triggered by the report of a volunteer who had observed the dissemination in the course of his pilotage work.

Provisional arrest / resistance and delivery

The provisional arrest of a person who was found redacted or found after persecution was not only the responsibility of the volunteer in the GDR, but everyone. This right is also established in the current social order of the FRG. The provisional arrest (also preventing an offender from escaping) always ends with the handover to a police officer or an authorized person. In the case of the GDR helper with handover to a VP member. If a person is provisionally arrested on the basis of urgent suspicion, their personal details must first be determined and then handed over to the TP. If the person resisted their arrest, the helper had to ask them for the last time to comply with the measure (the removal). In the event of a refusal, the necessary measures had to be taken to comply with the law, possibly with the help of people to arrest the perpetrator. Whether the necessary measures were also carried out with physical violence and / or punishment cannot be determined, but it is conceivable in individual cases. Resistance could not be challenged by the helper's clever, prudent and confident action. In addition, resistance to state measures was committed by anyone who prevents a member of a state body by using force or threating with force or another significant disadvantage from the dutifully performed state tasks assigned to him to maintain order and security, or who the act against a citizen, but also against the volunteer himself. The supply of people in the police in the course of a preliminary arrest was the right after short-term measure restricting the liberty that was to rule that the workers are not with an identity card demonstrative person or due to an urgent Tatverdachtes immediately to the VP supply had when this to clarify a situation through which order and security appeared necessary. It begins with the verbal notification of the helper by giving the person concerned the reason for the transfer, and ends with the handover to a VP member, but also if the person decides to identify himself on the way to the office due to a rethink.

Carrying out traffic instruction and holding driving tests

Carrying out traffic instruction was the responsibility of those voluntary helpers with special powers. This traffic instruction was a briefing of those persons who were summoned to “tutor” by the People's Police because of misconduct in traffic due to a lack of legal knowledge. In this case it was not uncommon for technically and pedagogically qualified volunteers of the traffic police to conduct these training courses. Such helpers were also not uncommon in the GDR for the acceptance of theoretical and practical basic and final exams to obtain a driving license. However, the driver's license was always issued by the People's Police.

Other points

The monitoring obligations of the volunteer do not end with the list of measures mentioned. The non-exhaustive catalog contains further points and thus duties of the helper, which could be location-specific:

- General assistance

- Burning of meadows, embankments, fields, wasteland and other areas

- Alarm system damage - abuse and destruction

- Ash deposit control

- Outdoor swimming pool control and surveillance

- Construction site security

- Crop protection

- Fireworks usage

- Pedestrian controls

- Gas leaks

- Eliminating and safeguarding hazards, troubleshooting

- Green area control

- Control of public stops

- Control of children's play streets

- Correct storage of items

- Convoy security and escort

- Curfew control

- Control of the litter requirement

- Sale and use of air guns

- Found ammunition and treatment of found weapons

- Notification of defects / notifications

- Registration control

- No smoking control

- Property damage to machines, telephones

- Student guide

- Prevention of cruelty to animals

- Rabies transmission

- Drunkenness in Public

- Monitoring the serving of alcohol

- Monitoring of the proper parking of motor vehicles

- Monitoring of fire protection on campsites

- Surveillance of citizens at risk of crime through special control measures

- Monitoring public collections

- Monitoring of railway facilities and level crossings

- Monitoring of entrances and exits in and out of properties

- Monitoring of escape and rescue routes

- Monitoring of the stay of children and young people (dance events, cinema visits)

- Keeping public streets, paths and squares clean

- Preventing disturbances and trespassing

- Stop drinking bouts

- Event monitoring

- Burning waste outdoors

- Avoid jumping on and off public transport

- Monitoring the reintegration measures of those released from prison into social life

Regulations

Employment requirements and suggestion system

In principle, every citizen of the GDR who had reached the age of 18 and was fit for health could take up service as a volunteer for the People's Police. Until 1964, the age of 17 was considered. The voluntary but lost in practice some limitations: So many helpers followed recommendation or targeted propaganda of party leadership in county or district offices as well Kombinats- or utility lines, in order to promote a career in the hierarchy of the SED regime or by this honorable service a To be able to show a flawless socialist curriculum vitae, for example for admission to a degree. The only specific prerequisite for employment was that the prospective helper had the correct moral and politically socialist attitude in the sense of the social order of the GDR and was ready to assist the German People's Police or the border troops of the National People's Army in “ensuring or protecting the state order and the Protection of the national economy, the public property of the citizens and their security ”. The following official basic requirements also applied:

- Knowledge of the legal policy of the GDR, with the application of which all citizens were to be educated to voluntarily and consciously comply with legal norms, as well as to enforce the law together with them

- to maintain close contact with the workers in the field or area of activity and to deal with them honestly and correctly

- the rights of citizens to heed their suggestions and critical advice and to protect their legitimate interests

- the constant willingness to gain further qualifications

- to regularly take part in training courses and instructions

- the knowledge of the current situation in the area of operation as well as knowing one's own possibilities and responsibility to fulfill the task

- To be a personal role model in appearance and behavior in the work collective and in the leisure area

- high professional and social activity

- Exercise of conscious state discipline and strict observance of the laws of the GDR

- high vigilance, reliability and confidentiality

- Conscientious fulfillment of the assigned tasks

- Development of a spiritual creativity

The majority of the budding volunteers were members of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED). Although this was not a formal admission requirement, it was beneficial for an application. Even in the case of a later career desire in the People's Police, a previous activity as a university of applied sciences could only be an advantage. The volunteers were usually proposed by the National Front , the SED and the heads of the state and economic management bodies of the combines, companies and institutions, but also by their own work collectives and cooperative boards. At the latest with the announcement of this proposal, the word “voluntary” ended, because it was disadvantageous for the budding helper to refuse to “serve on behalf of socialism”. Refusing helpers had to fear reprisals in their professional life, which could have an impact, for example, in the allocation of kindergarten places for the children. In many cases one could speak of forced voluntary service as a helper. Unsolicited applications from people who volunteered on their own initiative, however, were considered the rule. The applications or suggestions received were then carefully checked by the police stations or the district headquarters and, after their evaluation, confirmed as volunteers if necessary. The budding volunteer undertook to actively support the German People's Police or the border troops of the GDR in fulfilling their tasks. His subsequent assignment took place according to the respective requirements, taking into account his knowledge and skills.

A “discharge” from service as a voluntary helper took place on application or due to “official incapacity” through the withdrawal of the confirmation by the People's Police or the National People's Army. There was no oath of oath as with the members of the People's Police or with the conscripts in the NVA.

Training and collaboration

In addition to the actual training, which consisted of instruction in the form of lessons, most of the knowledge transfer was based on the principle of " learning by doing ". Theoretical knowledge was primarily imparted on a political level, since the main administration of the German People's Police of the Ministry of the Interior committed itself as early as 1952 that the volunteers had to acquire a high level of political knowledge. For this reason, it issued a corresponding directive in March 1960 in order to qualify the volunteers who were recruited politically, ideologically and professionally so that they correspond to the “norms of socialist society” and to promote their development into “conscious citizens of the republic”. The technical instruction consisted of imparting and instruction in police tactical behavior, contained rules of conduct for security and cordoning measures as well as the establishment of basic knowledge in the field of socialist legality. Incidentally, the same training principle also applied to the border police volunteers. The latter helpers in particular had to be sensitized through appropriate training so that they could provide effective support for the NVA border troops. The tightened school instruction also brought immediate success. In 1961, during the harvest season, volunteers from the People's Police in the Halle district were present at over 5,000 fire safety controls and spoke at over 1,000 fire safety events. The better professional qualification not only benefited public safety and order, so in the first quarter of 1961 volunteers of the People's Police were able to detect almost 300 criminal acts that are punished by the People's Police. They were also involved in 123 fire-fighting missions and in May 1961 secured the international peace voyage with around 18,000 volunteers from the People's Police .

With the third and final introduction of the ordinance for volunteer helpers of the People's Police in 1982, the training of the helpers was still the responsibility of the People's Police. In order to achieve a high level of quality and social effectiveness in ensuring public order and security, they continued to be obliged to support a constant acquisition of a high level of “political and technical knowledge” by the helpers and to give them the principles of police work required for their work to convey. In addition to teaching the Russian language and imparting the Marxist-Leninist doctrine, the volunteers were primarily concerned with operational skills such as sport, the use of applied technology and the teaching of correct behavior when intervening, as well as correct and polite behavior towards the citizen. The cooperation with the People's Police on the one hand and the helpers at the border police on the other, based on these training courses, ultimately served primarily the complex prevention and control of criminal offenses, misconduct and administrative offenses, the elimination of their causes and conditions as well as defense and Elimination of other dangers and malfunctions that may arise.

Personal equipment and identification required

The personal equipment of the volunteer primarily included his functional bag, which was available in different designs and sizes. This was also due to the fact that much of the equipment came from the helper's personal property. The important point is that no helper was allowed to carry handguns on duty . Usually the standard equipment for a volunteer of the People's Police consisted of one

- Notepad or notebook

- blueprint

- Writing utensils ( pencil , eraser , etc.) and whistle .

In addition, he could carry smaller tools such as a screwdriver , combination pliers or functional pocket knife in his pocket . For crime scene forensics were at his blackboard chalk , graph paper , and if possible a camera available. VP helpers who were out on the night patrol also carried a torch, candle and matches. Standard equipment for all missions, however, was the emergency kit, which consisted of adhesive plaster, gauze bandage and scissors. Motorcycle or motor vehicle strips allowed heavy objects to be carried, such as hammers , tool boxes , rescue blankets , etc. Binoculars or protective goggles could also be used in addition to special equipment, depending on the area used. In the course of the operation alongside members of the People's Police, volunteers were equipped with a regulatory staff and / or a protective helmet. Every volunteer of the People's Police always wore an ID card wrapped in green during his service, which authorized him as a volunteer helper of the VP and which he had to show to the persons concerned without being asked to intervene. The ID was therefore also the legal legitimation of all volunteers.

Insurance and criminal justice protection

All volunteers enjoyed legal and insurance protection for the time of their supporting measures and activities . The expenses incurred in connection with the performance of the service were reimbursed by the People's Police. The insurance cover itself covered all citizens who suffered an accident during organized social, cultural or sporting activities. The insurance cover usually consisted of the company wage compensation and was legally treated like an accident at work . Organized social activities included all voluntary social activities, including the activities of voluntary helpers. These activities included a. Equated with the fulfillment of obligations of conscripts outside the military service, but also life-saving activities, state holidays and vacation events, etc. For the consequences of an accident, the helper was entitled to benefits in kind, accident pension, care allowance, special care allowance and allowance for the blind. In the event of death, the survivor was entitled to a funeral allowance and an accident survivor's pension. The granting of the benefit lay with the responsible social insurance company, and with those not insured with the social insurance of workers and employees. The underlying accident was within 4 days

- a) in the case of citizens with social insurance, the company or the cooperative,

- b) for pupils and students of the school or university or technical college,

- c) for all other citizens of the responsible social security

to display. In the case of voluntary helpers, it was usually sufficient to provide information to the section authorized representative as the superior or to the VP department. The institutions were then obliged to report this accident to the responsible occupational health and safety inspection in accordance with the legal provisions. The accident also had to be marked with GT (social activity).

The criminal law protection of voluntary helpers of the People's Police was guaranteed by § 112 StGB of the GDR: If a helper was prevented by the threat of violence or its use or in some other way from the dutiful realization of the powers assigned to him, that corresponded to the same factual requirement as an attack against one regular members of the People's Police or other state organs of the GDR.

Allowance and working hours

All volunteers of the People's Police were deployed on a voluntary basis . As a rule, this meant no payment, but in individual cases continued payment of the previous wage costs. Most of the voluntary work of the volunteers was sold as a service for the people and the fatherland, so there was a constant influx of volunteers. Far more important than any remuneration, which could also be in the form of irregular monetary bonuses, which could also be associated with the award of medals and decorations , was the helper's prospect of increased social standing and the associated preferences. Such benefits were, for example, the faster allocation of a telephone connection or the allocation of a passenger car with or without a waiting time. Furthermore, for granted in kind gifts, such as watches of the popular brand Glashutte , Ruhla or radios of all kinds. The working hours of the volunteers in the police were committed and were a week eight to ten hours depending helper. In addition, there were full-time helpers, mainly older people and retirees, who worked far more hours. However, here too the norm deviated from the standard, which was not least intended by the government. Combines and companies in which voluntary helpers went about their regular work were able to enormously increase the proportion of their hourly output for social activities. Of course, this also led to an increased reputation of the company in general, for example in the awarding of honorary titles such as the company of socialist work . If several volunteer helpers of the People's Police were employed in a company, their activities were largely "marketed" by the company director, the party or FDJ secretary, also by the responsible police station chief, the authorized officer or even their own collective.

General rules of conduct

The general rules of conduct were largely based on the rules of conduct of the People's Police. These goods:

- constant discipline and correct demeanor

- prudent and considered action

- Start and end every conversation with greeting (left hand on temple)

- General address of the citizen with " Mr. ", " Mrs. ", " Miss " but also " Comrade "

- identify yourself with the ID card for volunteers if you are self-employed

- Instructions were understandable and polite

- Give all possible support and help primarily to children and frail people (e.g. when crossing a busy street without a pedestrian crossing)

- to strengthen the relationship of trust with the citizens through their own correct behavior and action and thereby secure their support and participation

- Maintain secrecy towards unauthorized third parties about official matters.

In reality, however, it was not always possible to comply with the above-mentioned model catalog for the personal status of a volunteer helper, but this concerned not only the negative influence, but also the positive one. For example, there were also voluntary helpers with a high school diploma or university degree who were mentally superior to their supervisor in many ways, which in many places also triggered discomfort and resentment on the part of the ABV or the VP member of his / her helpers.

Questionnaire

Each volunteer helpers in the police or border guards had in the course of investigations or reports, the so-called W-issues from the inside out dominate. Since when the hustle and bustle at the scene of the crime or incident occurs, e.g. If, for example , an uncontrolled influx of people could threaten a considerably confusing situation even more chaotically, the helper could fall back on his W-questionnaire, which he always had to keep with him either in small book form or in the form of a slip in his ID card . In particular for the subsequent reports to the People's Police, the following catalog of questions had to be dealt with:

- When? (Time in day, month, year and time of the discovery or the occurrence)

- Who? (Personal details or personal description of the perpetrator, perpetrator, witnesses)

- Where? (City, district, street, house number, floor, description of the location)

- What? (Brief, clear presentation of the facts about the type of event, consequences and effects as well as violated legal norms)

- How? (Brief, clear description of the course of events, in particular the manner, circumstances and intensity)

- By which? (Presentation of the means and objects with which an act or act was committed)

- Whom? (Name of the injured party, in particular individuals, companies or institutions)

- Why? (Motive and motives of the perpetrator or the person acting - as far as can be determined and their causes)

- What was initiated? (Previous measures taken with time information, who was informed and who took over the further processing?)

In addition to these questions, the Volunteers of its control section as the number of VP (110) listed at another suitable location, the most important numbers Fire Department (112) or the German Red Cross (115) and various other phone numbers of his superiors ABVs, VP- Revier , City Council , Polyclinic , Electricity Works, Gas and Water Works, Arbitration Commission , Car Repair Workshop and Towing Services , Forestry Company and other important telephone numbers.

Basic tactical rules in patrol duty

As a rule, there were three types of patrol for the Volunteers of the People's Police, the foot patrol , bicycle patrol and motorcycle patrol . The former also with guard dogs. Car patrols are rare, but also occur, mainly in rural areas with a correspondingly larger task area. As a rule, the voluntary helpers were instructed directly on site by the section authorized representative. Focal points conveyed and objects presented that deserved special attention.

Foot patrol

- Take moderate steps, stop frequently and observe - do not move in the flow of passers-by.

- Choose and observe favorable locations at important points such as danger spots.

- adhere to fixed times and (monitoring) rooms.

- Submit or report situation reports to responsible VP members at set times.

- No smoking, drinking or eating while on patrol.

- Visit restaurants and other public buildings only for compelling reasons or by order together with the section authorized representative, independently only to check for the protection of children and young people, regulation, control of the police hour, etc.

- Consolidation of the understanding of the social forces resident in the area such as porters, tank attendants, sales staff.

- Keep in touch with VP members and other volunteers in the area and avoid standing together unnecessarily.

Bicycle patrol

- Drive slowly and constantly observe the surroundings

- Conscientiously comply with traffic regulations

- Interrupt trips, push the bike and patrol - stopping more often and watching

- Park your bike before intervening

- Use mobility with the bike - special hot spots that require careful observation, pass several times from different directions

Moped / motorcycle patrol

- Precise imprint of prominent observation points before patrols

- Select the travel speed so that the strip area to be driven can be clearly observed

- Compliance with traffic regulations

- Carry out foot stripes at defined breakpoints or take control

- park the vehicle properly when intervening in a situation

Night behavior

- Tactics of hearing and seeing a lot with your own cover.

- Adhere to a moderate sequence of steps and adequate distances to the house.

- stopping more often in inanimate places and observing the tactics mentioned above

- Surprising appearances in places that were only recently observed (to prevent possible “criminal elements” from adjusting to fixed processes).

- Never turn your back to people approaching from behind - turn around in good time, walk towards them or let them by.

- when intervening, keep your distance from the person while maintaining back freedom.

First aid measures

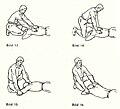

In the event of injuries or damage to people, the volunteers were often the first to reach the scene of the incident and, as part of their basic training in first aid, were also able to take the very first medical measures until the rescue workers arrived. In the socialist society, but also in today's police system, the life and health of people came first. The VP's volunteer helper understood first aid to mean providing the person concerned with first aid using the simplest of means, even under the most difficult and difficult conditions. The principle applied here: keep calm - act sensibly, logically and purposefully! . In detail, the work of the helper in the mountains , position control, first aid as well as transport for medical treatment or notification of a doctor included. To do this, the volunteer followed a strict chain of events:

- Rescuing the injured from the danger zone

- Calling the doctor or emergency services

- First aid

- Overview posture, calm and order

- Identification of the injured party

- Note down the personal details of the attending physician

- Write down the license plate number of the ambulance

As a result of the serious accident, assistance was no longer possible for the person concerned, e.g. B. through visible fatal physical impact, severed limbs, etc., the volunteer had to ensure that the scene of the accident was secured and to cover the person affected as much as possible. In the event of injuries, all volunteers have been trained to perform the following alternative assistance:

Rescue / wound treatment / arterial bleeding / bleeding

In the recovery of patients from a vehicle, the volunteers first had to prevent an imminent fire hazard. To do this, he had to pull out the ignition key, close the gasoline lines and provide any extinguishing devices such as hand fire extinguishers . Then the helper was able to carefully rescue the injured person with the help of tools such as jacks etc. while protecting injured parts of the body. He had to take into account that the casualty could have possible internal injuries. If this was to be assumed due to the severity of the accident, the helper had to prompt enough citizens of the surrounding area to provide help or to request other volunteers to ensure a better rescue. Under wound care each cut through the protective cover was to understand the body of the skin for the volunteer helpers. Each wound had to be covered with a sterile dry gauze dressing, whereby wounds should never come into contact with fingers or tweezers . They should also not be washed out or treated with ointments and powders. Foreign objects such as knives etc. had to be left in the body, and any change in position was prohibited in order to avoid serious damage. The doctor was then to be informed immediately. Injuries also had to be covered with germ-free material by the volunteer and tied with a stronger compress without any limbs such as fingers or toes possibly dying off. The helper could tell by the white or blue color of the extremities. If the bleeding did not stop despite the compress, the helper also had to put on a bandage that was placed a hand's breadth towards the heart. Injuries to larger vessels had to be appeased by hand pressure and then tied off. A whole bandage package was placed between the injury and the heart and fastened with a belt or similar. In this case, the helper had to fill out an accompanying note for the coming doctor, which included the time and his name. If after an hour still no doctor arrived, the constriction had to be loosened in order to prevent the affected limbs from dying off. The relaxation was also to be noted on the accompanying note. The venous blood flow was recognized for the carer in contrast to arterial injury by regular blood discharge from the wound. In this case, the helper applied a pressure bandage , whereby a protective bandage was sufficient for minor bleeding. He then took the injured person to the nearest house or hospital or called the ambulance service. The helper had to diagnose bleeding of internal organs (e.g. liver , spleen , kidneys , lungs or intestines ) by carefully observing the color of the face, since such injuries were noticeable by pale skin color and sweating. If this was the case, the injured person had to be placed in a quiet position and taken to the nearest hospital immediately, possibly by confiscating a passing vehicle.

Skull, spine and internal organ injuries

Injuries to the skull, especially skull fractures, could be recognized by the helper through bleeding from the nose , ears or mouth . Accompanied by dizziness in the victim or vomiting. If the person affected was unconscious, the volunteer would bring them into a stable position on their side without raising their head in order to avoid possible complications as far as possible. Spinal injuries could be recognized by the helper by pain and paralysis of the person concerned. In this case, the casualty was carefully placed on a table or a wide board with the help of several helpers and taken to the nearest hospital without being repositioned, with the greatest care, unless an emergency medical service arrived. In the case of open fractures, the wound had to be treated first. Immediate danger to life for the accident victim arises from injuries to vital internal organs . In this case, the volunteer had to assume that the upper body was severely bruised, as occurred in rear-end collisions, which originated from the driver being trapped between the steering wheel and the backrest. It was recognizable for him by the shock of the casualty (if conscious), shortness of breath, blue-red face coloring and rattling breathing with coughing. If this was the case, the helper had to free the person from his position as much as possible and lie down in a half-sitting position, like on tree stumps and the like, and protect them from cooling down. If I stopped breathing, the helper started giving me my breath immediately.

Injuries to the open chest and abdomen