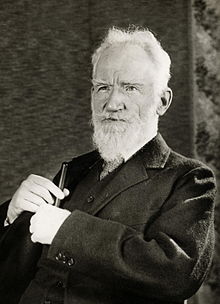

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw , usually just called Bernard Shaw at his own request (born July 26, 1856 in Dublin , Ireland , † November 2, 1950 in Ayot Saint Lawrence , England ), was an Irish playwright , politician, satirist, music critic and pacifist who Received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1925 and the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay in 1939 .

Life

Shaw came from a Dublin-based family of Scottish Protestant origin and grew up there in difficult family circumstances. His father, George Carr Shaw, was an unsuccessful grain dealer who had a drinking problem. His mother Lucinda Elizabeth Shaw, b. Gurly was a singer who separated from her husband shortly before G. Bernard Shaw's sixteenth birthday and moved to London with her two daughters and their singing teacher. Shaw initially stayed with his father. He suffered from severe social phobia , especially in his youth .

Shaw first worked as a commercial clerk, but soon moved to London to gain a foothold as a music and theater critic. In order to develop his prose, he wrote five novels between 1879 and 1883 , which were rejected by various publishers . Finally, he celebrated his first successes as a music critic for the newspaper Star , for which he wrote masterly ironic comments . For example, he discussed the compositions of Ethel Smyth under the pseudonym "Corno di Basseto" ( basset horn ). Shaw was one of the first music critics to refuse to attach any importance to the gender of the composer in evaluating the work. In 1923 he asked the now ennobled Ethel Smyth in a letter how masculine the work of Handel and how feminine the work of Mendelssohn and Arthur Sullivan actually are.

After reading the works of Percy Bysshe Shelley , he became a vegetarian in 1881: "It was Shelley who first opened my eyes to how barbaric my diet was," Shaw said in a 1901 interview. The vegetarianism played henceforth an important role for him; he understood it as a political matter and spoke in this context of solidarity, of "expanding the area of the feeling of togetherness". In 1882 he was reading Das Kapital by Karl Marx in the French translation (transfer into English did not exist). “That was the turning point in my career. Marx meant a revelation, ”he reported later. In 1884 he joined the intellectual-socialist Fabian Society (Society of Fabians), where there were personal overlaps with the vegetarian National Food Reform Society . He soon played a leading role in the Fabian Society, which was not aiming for social change in a revolutionary way, but rather in an evolutionary way. There he was able to spread his political ideas as a speaker. It was in this society that Shaw met his future wife, Charlotte Payne-Townshend, whom he married in 1898. Shaw is also considered a co-founder of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), in which the Shaw Library still commemorates him today.

In 1895 Shaw became a theater critic for the Saturday Review. This step initiated his future path as a playwright. In 1898 his first successful piece, Candida, appeared. Several comedies followed, such as The Devil's Student (1897), Arms and the Man ( Heroes ) (1898), Mrs. Warren's Trade (1898), Captain Brassbound's Conversion (1900), Man and Superman ( Man and Superman ) (1902), Caesar and Cleopatra (1901), Major Barbara (1905) and Androclus and the Lion (1912). Pygmalion , released in 1913 , later became the basis for the musical and film My Fair Lady . For Shaw, World War I represented the last desperate breaths of the 19th century empires. After the First World War he wrote more serious dramas such as Haus Herzenstod (1919) and Die heilige Johanna (1923). Shaw was a writer well into the old age of 90. In the last creative period (1930–1949) he paid more and more attention to political problems and merged fantastic and satirical elements.

As a representative of intellectual theater , Shaw created a new type of drama - the discussion drama , whose heroes clash as bearers of certain ideologies . Shaw's main interest is not the plot, but the clash of opinions, the discussions about philosophical, moral, political problems that his heroes lead. Shaw often resorts to satirical exaggeration and the grotesque, his heroes are not infrequently eccentric. In 1925 Shaw received the Nobel Prize “for his work, which is based on both idealism and humanity, in which fresh satire is often combined with a peculiar poetic beauty”.

A special feature of Shaw's publications are the long forewords . In these he presents the topics and problems dealt with in the plays in detail, so that the forewords are sometimes longer than the plays themselves. Thereupon rumors circulated in the fan base that Shaw is said to have declared: “I write my forewords for the intellectuals and my plays for the dummies. "(" I write my forewords for the intellectuals and my dramas for the stupid. ")

Shaw's destruction of conventional forms of drama such as well-made play , melodrama , farce or historical drama is just as characteristic of Shaw's dramatic work . He uses quotes from these genres of drama and uses them to generate a fore-pleasure in order to then show the viewer their lack of reality through inversions and disillusions. For example, Shaw's first drama Widowers's Houses (1892) was created based on a scenario designed by William Archer in the style of well-made play . Shaw, meanwhile, consumes the fable with the second act and in the third act lets a discussion and analysis of the social contexts and causes of the events depicted follow. Shaw remains true to this approach in his extensive dramatic oeuvre: the idealistic disguised motifs and illusions of the characters and actors are confronted with reality and thus made conscious as such. In the 1890s, however, Shaw's understanding of reality changed from a sociologically founded concept of reality to a biological-religious one after the turn of the century. His dramas change from realistically oriented pieces to utopian-visionary ones: Widowers's Houses and Mrs. Warren's Profession (written in 1893 ) contrast with the parable Back to Methuselah (1922).

In Shaw's conception of the drama, form and style no longer form independent meanings, but are subordinated to the purpose of analyzing reality and convincing the viewer. In contrast to conventional views, Shaw uses his own comprehensive biological and socio-political knowledge in a rhetorically accurate and at the same time witty form, on whose persuasiveness he trusts. In this regard, together with Bertolt Brecht , he founds an enlightening, didactic form of modern theater that intends to steer a changing world in the “right” direction by criticizing prejudices and reconstructing reality. A mere documentary or photographic representation of social conditions would neither do justice to such an intention nor to the increasingly complex social conditions. In order to uncover the problems in the relationship between humans and the environment, which also includes the social and cultural structures created by humans, Shaw primarily uses the parable or parable.

This construction is intended to reveal the truth that is hidden behind the social and linguistic-rhetorical surface. With the help of discussions of ideas, montages and provocative allegorical reinterpretations, Shaw tries to dissolve traditional myths such as heaven , hell , paradise or the fall of man and traditional literary motifs such as St. Joan or Don Juan in order to provoke a shock of knowledge in the audience. In Back to Methuselah , for example, the fall of Adam and Eve is by no means a misfortune. Rather, the emergence of sexuality, reproduction and death opens up a spectrum of possibilities to escape the unbearable boredom of eternity without endangering the continued existence of the human species.

Shaw's correspondence with Stella Patrick Campbell was also staged as a drama by Jerome Kilty entitled Dear Liar: A Comedy of Letters . His letters to the famous actress Ellen Terry have also been published and adapted as a play. His letters to H. G. Wells and to Gene Tunney are also published. His close friend and antagonistic discussion partner was Gilbert K. Chesterton , whose Catholic criticism of capitalism he valued as much as his sharp wit and who published a biography of him in 1909.

Because of his anger with the English orthography , he donated part of his fortune to the creation of a new English phonetic alphabet, which was designed in the course of a competition by Ronald Kingsley Read and is named after the initiator Shavian alphabet ("Shaw alphabet"). While Shaw was alive, the only expression of his considerable fortune was a Rolls-Royce .

In the last few years of his life he loved to be around his home and garden at Shaw's Corner to stay and tend the garden. He died of kidney failure (caused by the fall of a tree on him) at the age of 94 . On November 6, 1950, he was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium in London . His ashes, mixed with Charlotte's, were scattered in the garden on the sidewalks and around the statue of Saint Saint Joan , about which he had also written a drama in 1923.

Before his death, Shaw's name was known far beyond the British Isles. Shaw was the only Nobel Laureate to receive an Oscar until 2016, when Bob Dylan was also awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. He received the Oscar in 1939 for the best screenplay for the film adaptation of Pygmalion under the title Pygmalion: The novel of a flower girl . Since 1943 he was an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters .

politics

Shaw took an active part in politics throughout his life. From 1897 he was a council member in the St. Pancras district in London for years . He is one of the creators of the founding program of the British Labor Party in 1900. At the beginning of the First World War, he published a large article in 1914 in which he called the United Kingdom and Germany to negotiate and criticized blind patriotism . He remained a staunch opponent of the war during and after World War I.

In 1931 he met Mahatma Gandhi in London , who was there to negotiate with the British government. In March 1933 he traveled to Japan and expressed himself very critical of the Japanese hegemony policy in China (→ Second Sino-Japanese War ) in a conversation with the Japanese Army Minister Sadao Araki :

“The European was imperialistic, yet it led to the disappearance of three empires. Have you in Japan ever thought that in your imperialistic aims you may end as a republic, and that is not at all what your rulers want? […] If you had been born in Russia, you would have become a politician greater than Stalin […] I would like to stay here talking to you until the Chinese land on the Japanese mainland. ”

“The European War was imperialist, but it led to the disappearance of three empires. In Japan, did you ever think that your imperialist goals might end up being a republic, which is not necessarily what your rulers want? […] If you were born in Russia, you would have become a bigger politician than Stalin. [...] I would like to continue chatting with you here until the Chinese land on the Japanese heartland. "

Shaw also traveled to the Soviet Union in the 1930s . His works were published there with the help of Artemi Chalatow . In the foreword to the play On the Rocks (1933) he defended the forced collectivization in the Soviet Union . At the height of the Great Depression in 1931, he made a US radio broadcast calling on every able worker to travel to the USSR. Defending the Stalin purges, Shaw declared:

"We cannot afford to give ourselves moral airs when our most enterprising neighbor [that is, the USSR] humanely and judiciously liquidates a handful of exploiters and speculators to make the world safe for honest men."

"We cannot afford to behave highly morally when our bold neighbor [the Soviet Union, note] liquidates a handful of exploiters and speculators in a humane and fair manner in order to protect the world for the decent."

Shaw was a believer in eugenics and advocated government and educational measures in reproduction to improve genetic makeup.

Works

Plays

- The Houses of Mr. Sartorius or The Houses of My Father (Original: Widowers' Houses ), Comedy (1892)

- The Lover (Original: The Philanderer ), original version: The Heartbreaker , Comedy (1893)

- Heroes (Original: Arms and the Man ), Comedy (1894)

- Mrs. Warren's Profession (Original: Mrs. Warren's Profession ), Drama (1894)

- Candida , Mystery (1895)

- The Man of Destiny (Original: The Man of Destiny ), Comedy (1896)

- The Devil's Disciple (Original: The Devil's Disciple ), melodrama (1897)

- You never know (Original: You Never Can Tell ), Comedy (1898)

- Caesar and Cleopatra , Comedy (1898)

- Captain Brassbound's Conversion (Original: Captain Brassbound's Conversion ), comedy (1900)

- The Boxing Match (Original: The Admirable Bashville ), Comedy (1901)

- Man and Superman (Original: Man and Superman ), Comedy (1902)

- John Bull's Other Island (Original: John Bull's Other Island ), Comedy (1904)

- How he lied to her husband (Original: How He Lied to Her Husband ), drama (1904)

- Major Barbara , Comedy (1905)

- The Doctor at the Crossroads or The Doctor's Dilemma (Original: The Doctor's Dilemma ), Comedy (1906)

- Married (Original: Getting Married ), Comedy (1908)

- Blanco Posnet's Awakening (Original: The Shewing-Up of Blanco Posnet ), Drama (1909)

- Mesallianz or wrong number (Original: Misalliance ), Comedy (1910)

- Fanny's first play (Original: Fanny's First Play ), Comedy (1911)

- Androcles and the Lion (Original: Androcles and the Lion ), Comedy (1912)

- Pygmalion , Comedy (1913)

- Haus Herzenstod (Original: Heartbreak House ), comedy (1919)

- Back to Methuselah (Original: Back to Methuselah ), Parable (1921)

- Saint Joan (Original: Saint Joan ), Dramatic Chronicle (1923)

- The Emperor of America (Original: The Apple Cart ), comedy (1929)

- Too true to be good to (Original: Too True to Be Good ), Comedy (1931)

- Rural Commercial (Original: Village Wooing ), Comedy (1933)

- Stuck (Original: On the Rocks ), Comedy (1933)

- The island of surprises (Original: The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles ), game (1934)

- Die Millionärin (Original: The Millionairess ), Comedy (1935)

- Too Much Money (Original: Buoyant Billions ), Comedy (1936, 1946–1948)

- Geneva (Original: Geneva ), Drama (1938)

- The golden days of the good king Karl (Original: In Good King Charles' Golden Days ), drama (1939)

Film adaptations

- 1939: The novel of a flower girl ( Pygmalion )

- 1940: Major Barbara

- 1945: Caesar and Cleopatra

- 1970: Caesar and Cleopatra (theater recording)

Novels

- Cashel Byron's Profession (Original: Cashel Byron's Profession ), Roman (1882)

- The Amateursozialist (Original: An Unsocial Socialist ), Roman (1883)

- Künstlerliebe (Original: Love Among the Artists ), Roman

- The foolish marriage (Original: The Irrational Knot ), novel

- Immature or young wine ferments (Original: Immaturity ), Roman

- The Puritan and the nun or letters to a nun , novel (1958)

additional

- Common sense in war (Original: Common Sense About the War ) (1914), in: What I Really Wrote About the War (1930)

- The Illusions of Socialism (Original: The Illusions of Socialism ) (1897), German in: Essays (1908)

- Guide for intelligent women to socialism and capitalism (Original: The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism and Capitalism ), German by Siegfried Trebisch and Ernst W. Freissler, 550 p., Fischer, Berlin 1928

- Ein Wagnerbrevier (Original: The Perfect Wagnerite ) (1896)

- Handbook of the Revolutionary (Original: The Revolutionist's Handbook ) (1902)

- A Negro Girl Seeks God (Original: The Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God ), Legende (1932); German by Siegfried Trebitsch u. with 20 woodcuts by John Farleigh . Artemis, Zurich 1948, and in the Suhrkamp Library, Volume 29, Frankfurt a. M. 1962

- The prospects of Christianity (Original: On the Prospects of Christianity ) (1912)

- The last spring of the old lions (Original: The Last Spring of the Old Lion )

- Music in London (Original: Music in London )

- Shaw on Music, ed. Eric Bentley. New York: Applause Books 1995, ISBN 1-55783-149-1 . Collection of Shaw's concert reviews (1962, posthumous)

- Politics for Everyone (Original: Everybody's Political What Is What? ), Essay (1944)

- Socialism and human nature (Original: The Road to Equality ) Frankfurt a. M .: Suhrkamp 1973

- Socialism for millionaires. 3 essays, 1st edition. Library Suhrkamp, Volume 63, Frankfurt a. M. 1979, 1982, ISBN 3-518-01631-8

- Freedom Beyond the Grid - The Abbess Laurentia and Bernard Shaw

- The Catechism of the Subversive . Epilogue from Mensch und Übermensch , separate text. Frankfurt a. M .: Suhrkamp 1964

- Why for Puritans? Prefaces. dtv, Munich 1966

- Foreword for politicians . Frankfurt a. M .: Suhrkamp 1965

- Sixteen autobiographical sketches . Frankfurt a. M .: Suhrkamp 1964

- Do we agree? A debate between GK Chesterton and Bernhard Shaw with Hilaire Belloc in the chair. Palmer, London 1928

literature

- Lorenz Nicolaysen: Bernard Shaw, a philosophical study. Philosophical series 67. Rösl, Munich 1923.

- GK Chesterton : George Bernard Shaw, Phaidon, Vienna 1925.

- Herbert Eulenberg : Against Shaw - A polemic, Reissner, Dresden 1925.

- Gerhard Kutzsch : The "Candida" case. A critical study of George Bernard Shaw , undated 1941.

- Michael Holroyd : Bernard Shaw, Mage of Reason. A biography. Original title: Bernard Shaw. Translated by Wolfgang Held . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-518-40722-8 .

- Thomas Kluge: Bernard Shaw for the wicked. Frankfurt am Main, Leipzig: Insel-Verl. 2006. (Insel-Taschenbuch. 3205) ISBN 978-3-458-34905-1 .

- Hesketh Pearson: George Bernard Shaw. Geist und Ironie (Original title: Bernard Shaw. His Life and Personality, translated by Otto Schütte with the assistance of Hartmut Georgi and Isabel Hamer). In: Heyne biographies. Munich: Heyne 1981. (Heyne Taschenbuch. 79.) ISBN 3-453-55080-3 .

- Hermann Stresau: GB Shaw represented with self-testimonies and picture documents (= Rowohlt's monographs. Volume 59). Reinbek near Hamburg: Rowohlt, 12th edition, May 2001, ISBN 3-499-50059-0 .

- Albrecht Grözinger: Shaw, George Bernard. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 9, Bautz, Herzberg 1995, ISBN 3-88309-058-1 , Sp. 1596-1598.

Web links

- Literature by and about George Bernard Shaw in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about George Bernard Shaw in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about George Bernard Shaw in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- George Bernard Shaw in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Works by George Bernard Shaw in Project Gutenberg ( currently not usually available to users from Germany )

- George Bernard Shaw - Biographical . On: Nobelprize.org (official website of the Nobel Foundation). Retrieved March 8, 2014. (In English)

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the award ceremony for George Bernard Shaw in 1925

- George Bernard Shaw - Quotes and Biography (English)

- George Bernard Shaw - Quotes and Sayings

- Quotes & aphorisms by George Bernard Shaw

- Well cited: George Bernard Shaw

- George Bernard Shaw, Playwright, Author - Biography

- George Bernard Shaw Biography on Spartacus Educational

- George Bernard Shaw Biography in The Literature Network

- Classics of world literature - Bayerischer Rundfunk Fernsehen

- George Bernard Shaw The Marxist Reference Archive

- Information about George Bernard Shaw especially for schools on the education server SwissEduc (English)

- Background information on Shaw's Nobel Prize in 1925 at literatur-nobelpreis.de

- Shaw's Corner in Ayot St Lawrence, near Welwyn, Hertfordshire - Country home of playwright Bernard Shaw for 44 years

Individual evidence

- ↑ Biography of Bernard Shaw , pbs.org.

- ↑ Bernard Shaw: a Brief Biography ( Memento of the original from October 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Cary M. Mazer, University of Pennsylvania .

- ↑ br.de: Between shyness and social phobia

- ^ A b Cary M. Mazer: Bernard Shaw: a Brief Biography. (No longer available online.) University of Pennsylvania, archived from the original October 7, 2013 ; accessed on August 3, 2009 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Günther Stolzenberg: Tolstoi, Gandhi, Shaw, Schweitzer: Harmonie und Frieden mit der Natur, Göttingen 1992, p. 94.

- ^ Matthias Rude: Antispeciesism. The liberation of humans and animals in the animal rights movement and the left, Stuttgart 2013, p. 93.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 92.

- ^ The Fabian Society: its Early History. By G. Bernard Shaw . A paper read at a Conference of the London and Provincial Fabian Societies at Essex Hall on the 6th of February 1892 and ordered to be printed for the Information of members.

- ↑ See Bernhard Fabian (Ed.): The English literature. Volume 1: Epochs and Forms . Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag, 3rd edition Munich 1997, ISBN 3-423-04494-2 , p. 425.

- ↑ See Hans Ulrich Seeber: Shaw and the renewal of British drama. In: Hans Ulrich Seeber (Ed.): English literary history . 4th ext. Ed. JB Metzler, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-476-02035-5 , pp. 334–338, here p. 335.

- ^ J. Percy Smith (Editor): Bernard Shaw and HG Wells . University of Toronto Press, 1995, ISBN 0-8020-3001-7 , pp. 242 .

- ^ Honorary Members: George Bernard Shaw. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed March 22, 2019 .

- ↑ David Bergamini: Japan's Imperial Conspiracy, Heinemann London 1971, pp. 545-546.

- ^ Robert Service: Comrades! A History of World Communism. Harvard University Press, Cambridge / Mass., 2007 ISBN 978-0-674-02530-1 , p. 206.

- ^ Paul Gray: Cursed by Eugenics. Time Magazine World on Time.com, January 11, 1999, accessed September 5, 2012 .

- ^ Geoffrey Russell Searle: Eugenics and politics in Britain, 1900-1914 . Noordhoff International, Groningen, Netherlands 1976, ISBN 978-90-286-0236-6 , p. 58.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Shaw, George Bernard |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Irish writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 26, 1856 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Dublin , United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 2, 1950 |

| Place of death | Ayot Saint Lawrence , England |