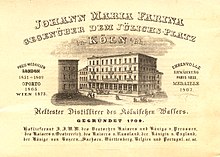

Johann Maria Farina across from Jülichs-Platz

| Johann Maria Farina across from Jülichs-Platz

|

|

|---|---|

| legal form | GmbH |

| founding | July 13, 1709 |

| Seat | Cologne , Germany |

| management | Johann Maria Farina managing partner |

| Branch | Perfume industry |

| Website | www.farina1709.de |

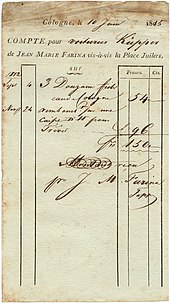

The company Johann Maria Farina opposite Jülichs-Platz GmbH was founded on July 13, 1709 as G. B. Farina in Cologne and is today the oldest existing eau-de-Cologne and perfume factory in the world. Her sign is a red tulip. The company name was also used in French for a long time - "Jean Marie Farina vis-à-vis de la place Juliers depuis 1709" - and often abbreviated as "Farina opposite".

Farina was a privileged supplier to many farms in Europe.

The perfume factory is now run by the founder's five-time great-grandchildren in the eighth generation. The headquarters and birthplace of Eau de Cologne is the “Farina House”. The Cologne Fragrance Museum is located in the house .

Company history

From the origins to the death of Johann Maria Farina (I), 1709–1766

Beginnings

The Farina family had lived in the small Italian community of Santa Maria Maggiore since the mid-15th century . The deep connection with the place they helped to found is evident among other things. a. in the family seal, which represents an eagle and a sack of flour with ears of wheat and which still adorns the family's old residence in Santa Maria Maggiore.

In June 1709 Johann Baptist Farina (1683–1751) came to Cologne, where his younger brother Johann Maria Farina (1685–1766) had lived in Grosse Budengasse as his uncle's representative since 1706. As a trading city with civil rights, Cologne was suitable for establishment and was not yet included in the then international network of Italian dealers. On July 13, 1709, Johann Baptist Farina (Italian: "Giovanni Battista Farina") founds the company GBFarina with the purchase of goods and the start of bookkeeping, which has been continued without interruption until today. The first journal entries are all purchases. On July 24, 1709, Johann Baptist Farina qualified as a so-called “extra-urban” with the City Council of Cologne, this so-called minor citizenship was the prerequisite for being able to become self-employed as a merchant in Cologne (Council Protocol No. 156 with the killing of 20 Reichsthalers) . On August 1, 1709, Johann Baptist Farina (II), with the support of his uncle, the Maastricht councilor and merchant, and his younger brother of the same name, Johann Maria Farina (Italian: “Giovanni Maria Farina”), rented rooms “in der Große bottengassen und Goldschmidts orth ”(today: Unter Goldschmied) in Cologne. The sale only begins after the shop is rented after August 1, 1709. The company GBFarina was then renamed "Farina & Compagnie" in the course of 1709 after the partner and brother-in-law Franz Balthasar Borgnis was accepted the addition of his brothers Johann Maria Farina (I) and Carl Hieronymus Farina was renamed “Gebrüder Farina & Comp.”. On July 29, 1711, Johann Baptist Farina acquired the great citizenship (Citizens Registration Book C658). He qualified as a member of the Schwartzhauß gaff . Since Farina practiced a trade without a guild , he was not a member of a Cologne guild . The Farinas ran a business with so-called "French stuff" ( gallantry and silk goods such as gold and silver cords, ribbons and braid, silk stockings and handkerchiefs, tobacco boxes, sealing wax, feathers, wigs, powder and the like) and worked with them in one for Italian merchants in Germany since the Middle Ages typical trade division. After Johann Maria Farina joined the company in 1714, the purchase of essential oils and other fragrances for perfume production began, which Johann Maria Farina had already made, as his correspondence shows.

After the company "Gebrüder Farina & Comp." Got into financial difficulties several times in the years after 1716, Franz Balthasar Borgnis and Carl Hieronymus Farina left the business and Johann Baptist (II) and Johann Maria Farina (I) ran it under the Name "Fratelli Farina" or "les frères Farina" (German Farina brothers ) continued. In 1718 the two brothers reached a settlement with their creditors. In the following years, the commission and forwarding business was very dominant alongside proprietary trading and in-house production, but overall business development hardly made any headway.

From March 1, 1733, the company operates as "Johann Maria Farina"

Johann Baptist Farina (II) died on April 24, 1732. In the following months Johann Maria (I) made an inventory and continued the business from 1733 under the name "Johann Maria Farina" which still exists today. On March 20, 1733 he wrote in a letter to Ferrari in Antwerp:

“… Li negoti continuati d'una lunga serrie d'anni sotto il nome a di fratelli Farina esendosi terminati p la morte di mio fratelo Gio Battista o resoluto con la beneditione del Sieur di rinovarlo sotto mio proprio conchi vi prego continuare a honorarmi de vostri commandi. "

"... Since the business relationships that had existed for many years under the name of the Farina brothers have come to an end with the death of my brother Johann Baptist Farina, I have decided, with God's help, to continue the company under my own name, and I ask you to honor me furthermore with your orders. "

The company's position seems to have improved very soon after this takeover. In a letter dated May 31, 1733 to his cousin Francesco Barbieri in Santa Maria Maggiore , Johann Maria (I) wrote:

“… Comintio avanzare in eta e si come laudato a dio che ho fatto il primo e il piu difficile fondamento di questo mio negotio che mi da pane cotidiano e che va dun giono a l'altro semper di bene in meglio, il mio bramo col tempo sarebe di vedere in mia piaza un giovine proprio di podere continuare e reduplicarlo… ”

“... I have come to the point that the first difficult beginnings of the business that gives me my daily bread are getting better day by day. It is up to me to see the business continue and double as time goes on ... "

Just two years after Johann Maria Farina (I) took over the sole management of the business, he acquired the great citizenship of the city of Cologne. The corresponding entry in the registration book also shows that Farina had in the meantime moved the business to the corner of Obenmarspforten / Jülichsplatz (renamed Gülichsplatz from 1815), where the company is still based today.

Overall, the company experienced a strong upswing in the 1730s and 1740s, which was based primarily on the freight forwarding business operated by Farina , while the trade in scented water only came to the fore in the 1760s.

Eau admirable Farina

Even before he joined the “Farina & Compagnie” company in 1714, Johann Maria Farina (I) had already produced a scented water called “Eau admirable”. The historian Wilhelm Mönckmeier suspects that the recipe and manufacture of this product was Johann Maria's contribution to the business of his brother and his partner. While the term "Eau admirable" (also Latin " Aqua (ad) mirabilis ") originally served as a generic term for various miracle waters produced with the help of the distillation process, Farina used a new production process in which a mixture of essential oils in high-percentage wine spirit has been resolved. This use of fragrances in alcoholic solution was an innovation brought to Germany by Italian families such as Farina's.

Another novelty was the fragrance itself, whose freshness and lightness stood out clearly from the heavy fragrance essences such as cinnamon , sandalwood or musk that were often used up until then . Johann Maria Farina (I) wrote to his brother Johann Baptist (II) in 1708:

“I found a scent that reminds me of an Italian spring morning, of mountain daffodils, orange blossoms shortly after the rain. It refreshes me, strengthens my senses and imagination. "

For the top note of bergamot , the citrus fruits were harvested green before the fragrance essence was extracted from their peels. The particular difficulty in the later production of the fragrance was that the harvest each year - as with wine - produced different aromas depending on the climatic conditions. The perfumer was therefore faced with the challenge of ensuring a consistent composition by mixing different essences. In order to guarantee an exact repetition of the scent, Farina created reserve samples, some of which have been preserved to this day.

“Eau de Cologne” conquers the European market

Johann Maria Farinas (I) trading with Eau admirable was initially limited to the retail trade in Cologne and sales at trade fairs in Frankfurt am Main . A dispatch of the goods abroad is documented for the first time in the company's letter copy books for the year 1716, when Farina sent twelve bottles of four livres each to a Madame Billy in Aachen . In the 1720s, shipments were still small in terms of quantity, but the spread already extended to Paris, where Farina sent the first shipment of 24 bottles in November 1721. In the 1730s the customer base expanded. Mönckemeier registered the dispatch of around 3,700 bottles to a total of 39 addresses for the years between 1730 and 1739. Farina herself mentions shipments to France, Spain, Portugal, England, the Netherlands, Germany and Italy in a letter of August 9, 1737. The eau admirable enjoyed growing popularity, especially among the nobility . In a letter dated August 31, 1734, Farina reported to the Berlin merchant Fromerey that he had also supplied the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm . Officers of the French army who returned to their homeland from the Rhineland after the war of the Polish Succession to the throne , created a market for the goods in France. The name "Eau de Cologne" dates from this period and appears for the first time in the company papers in a letter from Farina to the Baron von Laxfeld in Münster on June 22, 1742:

"Monsieur Peiffer d Bacharach me fait voir une de vous lettre par laquele vous luy demande six boutellie de Eau de Cologne. Cet ensi que on lapelle en France, mais en soie mesme cet de leau admirable, et je suis le seulle qui faie de la veritable… »

“Mr. Peiffer from Bacharach showed me one of your letters in which you asked him for six bottles of the Eau de Cologne. That's what it is called in France, but it's the same as Eau admirable and I'm the only one who makes the real thing ... "

In the 1740s, sales increased steadily. Regular shipments went to Rouen , Paris , Strasbourg , Magdeburg , Trier , Wesel , Kleve , Lyon and Vienna . Farina also sent the goods to Amsterdam , The Hague , Liège , Lille , Aachen , Düsseldorf , Bonn , Braunschweig , Frankfurt am Main , Leipzig , Augsburg , Stuttgart , Bamberg , Mainz and Koblenz . In a letter dated April 9, 1747, Farina summed up that Eau de Cologne is now "known throughout Europe".

The trade in Eau de Cologne took off during the Seven Years' War . Farina supplied officers in the two French armies of the Rhine, for whom the scented water had meanwhile become a natural item of equipment alongside wigs, powder and other luxury items. The French officers, in turn, had the eau-de-cologne sent to their wives and friends back home. The proportion of French customers was so large that Mönckmeier came to the conclusion that Farina's Eau de Cologne trade in the 1750s and 1760s could almost be described as a purely French business. As far as the volume of trade is concerned, Mönckmeier estimates shipping for the period between 1750 and 1759 at 12,371 bottles, for the last seven years up to the death of Johann Maria Farina (I) at 27,393 bottles. When Farina died in 1766, trading in eau de cologne had almost become his company's main business.

Packaging, quality seals and advertising

Johann Maria Farina (I) had his Eau de Cologne bottled in elongated green bottles, the so-called "Rosolien" or "Rosoli flacons ". Whole rosolias with a capacity of 8 ounces and half to 4 ounces were sold. Quarter bottles of 2 ounces were also added in the 1760s. The best selling was the half bottle that Farina was selling for 6 Reichstaler or 9 guilders per dozen. Initially the goods were sold in bottles, later Farina sent the scented water in boxes of 4, 6, 8, 12 or 18 bottles.

The authenticity of the goods was attested by a red seal with the family coat of arms. In addition, each delivery was accompanied by printed instructions for use in the form of a slip of paper signed by the owner. According to these instructions for use, the water was not only intended for external use, but also provided the best service in the care of teeth, the removal of bad breath and the fight against contagious diseases. When a Madame Duplessis from Nogent asked Cologne in August 1785 whether her husband's paralysis could also be cured with eau de Cologne , Johann Maria Farina (III) replied that she should dip linen in the water and rub it on the painful areas. She can also add 50 drops to the well water three times a week. “At least,” the letter concludes, “don't risk harming him in any way”. Only in 1811 did the reference to the medical effects of the product disappear from the label. However, the notes were retained as a means of advertising. The handwritten signature of the owner was replaced in 1803 by a signature applied by means of a stamp, which made it possible to add a note to each individual bottle.

The company under Johann Maria Farina (III), 1766–1792

After the death of Johann Maria Farina (I) in 1766, his nephew Johann Maria Farina (III), a son of the company's founder Johann Baptist Farina, took over the management of the business. His uncle had taken him as an apprentice after his father's death in 1733, but then the two had fallen out and Johann Maria Farina (III) had entered the Dutch service as a soldier. Around 1747 he returned to Cologne and initially worked as an employee of his uncle. From 1749 he ran his own shop and a chocolate factory. At the same time he sold his uncle's eau de Cologne to Düsseldorf, where his brother Carl Hieronymus Farina had moved in 1717 after he left the company "Gebrüder Farina & Comp." Mönckmeier suspects that Johann Maria Farina (III) was called in as a future heir during the lifetime of Johann Maria Farina (I) in the manufacture of the scented water.

Since Johann Maria Farina (III) could not continue the eau de Cologne production, the shop, consignment and shipping business as well as the chocolate factory after the death of his uncle, he took Carl Anton Zanoli, an employee of his uncle, as a partner added. Zanoli, who had worked at Farina since 1747, brought his experience in commission and freight forwarding business to the table, but was not initiated into the secrets of eau de Cologne manufacture. He shared in the profit, but the six-year agreement between Farina and Zanoli remained secret. In the further history of the company, the involvement of a non-family business partner did not occur again; Mönckmeier does not attach any particular importance to the development of the house.

After separating from Zanoli, Farina (III) increasingly turned to the Eau de Cologne trade. The Business Journal has for ten years from 1767 to 1776 strong growth in the area of goods shipments outwards from:

| year | Quantity (in bottles) Price on average 1 Reichsthaler |

|---|---|

| 1767 | 3072 |

| 1768 | 3828 |

| 1769 | 2556 |

| 1770 | 2940 |

| 1771 | 3492 |

| 1772 | 5232 |

| 1773 | 6156 |

| 1774 | 6036 |

| 1775 | 6684 |

| 1776 | 7692 |

The geographic expansion of Farina's sales itself extended across Europe, with France still in first place. How the addressees of the programs distributed the Eau de Cologne on their part cannot be read from the available sources, but it can be assumed that the scented water reached a much wider group of customers, especially through the large commission houses in the port cities. A first direct shipment of Eau de Cologne to India is documented for the year 1776. At the end of the 1780s, Farina finally gave up its remaining business lines entirely in favor of the Eau de Cologne trade and chocolate manufacturing.

When Johann Maria Farina (III) died on June 30, 1792, he had not made any arrangements for the continuation of the company. The fact that the business was passed into the hands of his wife and sons also ended the time when an individual had run the company.

Development 1792–1914

The management took over from 1800 Johann Baptist Farina (IV), Johann Maria Farina (V) and Carl Anton Farina (VI).

From September 13th to 17th, 1804, Emperor Napoleon visited Cologne with his wife. His first valet Constant noted in his diary: "When we left Cologne, we had all bought a lot of Eau de Cologne from Johann Maria Farina. I only kept enough for the trip and I had the rest packaged."

In 1872 the company was raised to the position of kuk court supplier for Eau de Cologne.

The managing partners Johann Maria Friedrich Carl Heimann , Alexander Mumm von Schwarzenstein and Johann Maria Heimann hosted the celebrations for the 200th business anniversary in 1909.

From 1914 until today

The men's fragrance called Russian leather was created here in 1925 , inspired by the high-quality leather from Russia. The name was Germanized to Juchten in 1934 , and Eau de Cologne became Cologne water at the same time . The name Russian leather was revived in 1967. He was advertised with the security in the arms of manhood .

In 1927, the Doetsch, Grether & Cie company in Basel became the general agent for Farina in Switzerland. Sales to other countries were also taken over by the Dutch company until 1930. In 1943 Doetsch, Grether & Cie took over the export of Farina in trust so that it could continue to deliver to countries that were not directly accessible from Germany. Regular customers such as Thomas Mann and Marlene Dietrich could continue to purchase Farina Eau de Cologne during the Second World War. In addition, the necessary foreign exchange was generated in order to be able to continue buying essences abroad.

Marianne Langen, born in direct line of the founder, Heimann and her husband, Victor Langen , paid off the co-owners of Farina in 1959 and took over all the shares. They sold the company in 1975 to the French perfume and luxury soap manufacturer Roger & Gallet. After Roger & Gallet was taken over by the Elf Aquitaine concern in 1979 , Doetsch, Grether & Cie in Basel took over the shares from Farina in 1981. Since 1999 the Farina family has held all shares in the company in Cologne again. In 2003 Farina opened the Fragrance Museum in the Farina House.

Famous users and customers

- 1734 King Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia (soldier king )

- 1736 Elector Clemens August I of Bavaria

- 1738 Emperor Karl VI.

- 1740 Empress Maria Theresa of Austria

- 1745 King Louis XV. of France ; King Friedrich II of Prussia (Friedrich the Great; Old Fritz); Voltaire

- 1758 King Ferdinand VI. from Spain

- 1782 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- 1791 King Stanislaus II of Poland

- 1797 Queen Louise of Prussia

- 1799 Friedrich Schiller

- 1800 King Gustav IV of Sweden

- 1802 Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

- 1804 Emperor Napoléon I of France

- 1806 Archduke Anton Viktor of Austria

- 1807 Ludwig van Beethoven

- 1809 Caroline, Queen of Naples

- 1810 Pauline, Princess Borghese , Letizia Buonaparte , Jérôme King of Westphalia ,

- 1811 Empress Marie-Louise of France ; Emperor Franz I of Austria ; Hermann Graf von Pückler ; Elise, Grand Duchess of Tuscany

- 1815 Tsar Alexander I of Russia ; Alexander von Humboldt ; Prince Clemens von Metternich

- 1822 Emperor Peter I of Brazil

- 1824 Heinrich Heine

- 1830 King Wilhelm IV of Great Britain, Ireland and Hanover

- 1837 Victoria, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland

- 1841 King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia

- 1843 Tsar Nicholas I of Russia ; Paul Alexander Leopold Fürst zur Lippe

- 1845 Heinrich, Duke of Anhalt

- 1846 King Ernst August I of Hanover ; Adolph, Duke of Nassau

- 1847 King Christian VIII of Denmark and Norway

- 1848 Erich Freund, Duke of Saxony-Meiningen

- 1850 King Friedrich August II of Saxony ; King Frederick VII of Denmark

- 1855 Tsar Alexander II of Russia ; King John of Saxony ; Karl Alexander, Grand Duke of Saxony Weimar

- 1859 Georg Friedrich Karl, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg Strelitz

- 1861 King Wilhelm I of Prussia

- 1862 Friedrich Wilhelm, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg Strelitz

- 1863 Albert Eduard, Prince of Wales

- 1866 King Louis of Portugal ; Ludwig III, Grand Duke of Hesse

- 1868 Emperor Napoléon III. of France ; King Charles I of Württemberg ; Earl Benjamin Disraeli of Beaconsfield ; Friedrich, Grand Duke of Baden; Friedrich Wilhelm, Crown Prince of Prussia

- 1870 Alexandra, Princess of Wales

- 1871 Kaiser Wilhelm I.

- 1872 King Ludwig II of Bavaria (fairytale king)

- 1872 Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria, King of Hungary ; Empress Elisabeth of Austria, Queen of Hungary (Sissi)

- 1873 King Leopold III. from Belgium ; King Albert of Saxony

- 1874 King Oskar II of Sweden ; Victoria, Crown Princess of Prussia

- 1876 King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy

- 1877 King Christian IX. from Denmark ; Mark Twain ; Margaretha, Crown Princess of Italy; Amadeus, Duke of Aosta

- 1878 King Umberto I of Italy

- 1879 Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse

- 1880 King Wilhelm III. the Netherlands

- 1881 King Charles I of Romania

- 1882 Friedrich Franz II., Grand Duke of Mecklenburg Schwerin

- 1888 Emperor Friedrich III. ; Kaiser Wilhelm II ; Mori Ōgai

- 1889 Oscar Wilde

- 1894 King Otto I of Bavaria

- 1901 Emperor Edward VII of India, King of Great Britain and Ireland

- 1910 Emperor George V of India, King of Great Britain and Ireland

- 1921 Thomas Mann

- 1925 Franz Lehár

- 1927 King Gustav V of Sweden

- 1928 Konrad Adenauer

- 1935 Marlene Dietrich

- 1939 Heinz Rühmann

- 1951 Empress Soraya of Persia

- 1959 Indira Gandhi ; Romy Schneider

- 1964 Françoise Sagan

- 1970 Hildegard Knef

- 1987 Princess Diana of Wales

- 1999 Bill Clinton

Literature and Sources

swell

- Historical Archive of the City of Cologne (HAStK)

- Rheinisch-Westfälisches Wirtschaftsarchiv (RWWA) Foundation , Cologne

- National Library of France ( Gallica ): image 7–10

The company archive of the Farina house is now housed in the Rheinisch-Westfälisches Wirtschaftsarchiv Köln (Section 33). Some selected documents are available as digital copies in the Wikisource project (see below). Selection:

- Cologne water from Johann Maria Farina, the oldest distiller in Cologne, lives across from Jülichs-Platz , leaflet from 1811 on Wikisource .

- Delivery of Eau de Cologne to the French Empress Marie-Louise:

- Ingrid Haslinger. Customer - Kaiser. The story of the former imperial and royal purveyors . Schroll, Vienna 1996, ISBN 3-85202-129-4 .

- Florian Langenscheidt (Ed.): German Trademark Lexicon . German Standards, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-8349-0629-8 , pages 396-397

- Florian Langenscheidt (Ed.): Lexicon of German family businesses . German Standards, Cologne 2009, ISBN 978-3-8349-1640-2 , pages 447-448

- Literature by and about Johann Maria Farina opposite Jülichs-Platz in the catalog of the German National Library

Representations

- Hermann Schaefer: history, trademark protection, imitators, jurisdiction. Founded in 1709 from the archives of the original Johann Maria Farina house opposite Jülichs-Platz . Cologne 1929.

- Hermann Schaefer: The trademarks of the original Johann Maria Farina house opposite Jülichs-Platz, oldest Cologne water factory, founded in 1709 in Cologne a. Rh. M. DuMont Schauberg, 1925 and addendum 1929

- Wilhelm Mönckmeier: The history of the Johann Maria Farina house across from Jülichsplatz in Cologne, founded in 1709 , revised by Hermann Schaefer. Berlin 1934 (detailed description of the company's history from its beginnings to 1914 as well as a cursory overview of the period between 1914 and 1933).

- Markus Eckstein: Eau de Cologne: On the trail of the famous fragrance . Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-7616-2027-6 .

- Markus Eckstein: Cologne, cradle of Eau de Cologne , Bachem Verlag, Cologne 2013, ISBN 978-3-7616-2676-4 .

- Verena Pleitgen: The development of business accounting from 1890 to 1940 using the example of the Krupp, Scheidt and Farina companies. Dissertation thesis, University of Cologne, 2005

- Marita Krauss : The Royal Bavarian Court Suppliers. Where the king was a customer . Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-937200-27-9

- Astrid Küntzel: Strangers in Cologne. Integration and exclusion between 1750 and 1814 . Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-412-20072-5 .

- Rudolf Amelunxen: The Cologne event . Ruhrländische Verlagsgesellschaft, Essen 1952

- Bernd Ernsting, Ulrich Krings: The council tower . JPBachem Verlag, Cologne 1996, pp. 506 + 507 ff

- Rhenish-Westphalian economic biographies 1953, section 7, pages 161–198

- Jürgen Wilhelm (ed.): The great Cologne Lexicon . Greven Verlag, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-7743-0355-X .

- Klara van Eyll : The history of entrepreneurial self-administration in Cologne 1914–1997 . RWWA zu Cologne, pages 163, 234, 235

- Robert Steimel: Cologne heads . Steimel Verlag, Cologne 1958

- Ludwig Schröder: The branded article. Development - Structure - Tasks of the Brand Association, Wirtschaftsverlag, Wiesbaden, 1983, ISBN 3-922114-04-0 .

- Werner Schäfke (Ed.): Oh! De Cologne. The history of the cologne. With a contribution by Bernhard Kuhlmann: In any case, Eau de Cologne tastes better than petroleum . Wienand Verlag, Cologne 1985, ISBN 3-87909-150-1 .

- o. V .: To celebrate the company's 200th business anniversary - Johann Maria Farina across from Jülichs-Platz - , 1709–1909, Cologne 1909

- DIE ZEIT No. 46 - November 13, 1959, from the ZEIT ONLINE archive

Specialist publications related to Farina

- Friedrich Gildemeister, Eduard Hoffmann: The essential oils . 1st edition. Julius Springer, Berlin 1899

- Ludger Kremer; Elke Ronneberger-Sibold (Ed.): Names in Commerce and Industry: Past and Present . This includes Christian Weyer: brand name, indication of origin and free character in the border area between proprium and appellative . Logos Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-8325-1788-5 , pages 45-60

Specialist publications on the subject of Eau de Cologne

- Giovanni Fenaroli, L. Maggesi: Acqua di Colonia . In: Rivista italiana essenze, profumi, piante officinali, olii vegetali, saponi , vol. 42, 1960

- Francesco La Face: Le materie prime per l'acqua di colonia . In: Relazione al Congresso di Sta. Maria Maggiore, 1960.

- Sébastien Sabetay: Les Eaux de Cologne Parfumée . Sta. Maria Maggiore Symposium 1960.

- Frederick V. Wells: Variations on the Eau de Cologne Theme . Sta. Maria Maggiore Symposium 1960.

- Frederick V. Wells, Marcel Billot: Perfumery Technology. Art, science, industry . Horwood Books, Chichester 1981. ISBN 0-85312-301-2 , pp. 25, pp. 278

- Hugo Janistyn: Fragrances, soaps, cosmetics , Heidelberg, 1950

Farina in fiction

- Honoré de Balzac : Histoire de la grandeur et de la decadence de César Birotteau, perfumer Marchand, Adjoint au Maire du deuxième arrondissement de Paris, Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur-etc . (History of the greatness and decline of César Birotteau, perfume dealer, alderman to the mayor of the Second Parisian arrondissement, knight of the Legion of Honor, etc.). Paris November 1837

- George Meredith: Farina. A legend of Cologne Chapman and Hall, London 1894.

Web links

- Literature by and about Johann Maria Farina opposite Jülichs-Platz in the catalog of the German National Library

- Farina opposite (website of the company with a multilingual tabular outline of the company's history).

- Eau de Cologne - the fragrance that made Cologne famous (information from the Historical Archive Farina Haus, Cologne, edited by Johann Maria Farina. There is also a family tree of the Farina family ( memento from February 12, 2006 in the Internet Archive )).

- Fragrance Museum in the Farina House in Cologne (with numerous pictures and directions ).

- TV recording of the ceremony "300 Years of Farina" in Cologne City Hall on July 13, 2009

- Information about "300 years of Farina" in Cologne City Hall on July 13, 2009

- Usage list Eau Admirable around 1760

- Effect and virtues of the famous l'eau admirable, or Cöllnisch water called by Johann Maria Farina opposite Jülichs-Platz, around 1733–1800 in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (French).

- Prospectus by Johann-Maria Farina, across from Julichs-Platz à Cologne in the BIU Santé library network of the University of Paris Descartes.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hoppenstedt : Company database - large and medium-sized companies 2007

- ↑ Sabine Seifert: Early case of product piracy: Dat Wasser vun Kölle . In: The daily newspaper: taz . August 10, 2019, ISSN 0931-9085 ( taz.de [accessed November 11, 2019]).

- ↑ The numbering of the name, followed Mönckmeier The history of the house Johann Maria Farina , Annex, Annex 3. The names on the reproduced on the Web genealogy ( Memento of 12 February 2006 at the Internet Archive ) differ from those Mönckmeiers.

- ↑ Cologne population register from 1715, reprint and publication by the West German Society for Family Studies, New Series No. 17, Cologne 1981.

- ↑ Mönckmeier: Die Geschichte des Haus Johann Maria Farina , p. 9. Mönckmeier names the year 1717 as the date for the separation, ibid., P. 81.

- ↑ On this, Mönckmeier, Die Geschichte des Haus Johann Maria Farina , p. 12f.

- ↑ p. 17. The translation is reproduced in Mönckmeier's wording.

- ↑ Citizens Registration Book of the City of Cologne: “December 10 Johann Maria Farina, frantz. krahm, Obenmarktportz ”. Quoted here from Mönckmeier, Die Geschichte des Haus Johann Maria Farina , p. 18.

- ↑ Mönckmeier: The history of the house Johann Maria Farina , p. 6.

- ↑ p. 8.

- ↑ Eckstein, Eau de Cologne , p. 14f.

- ↑ Mönckmeier: The history of the house Johann Maria Farina , p. 58.

- ↑ Mönckmeier: The history of the house Johann Maria Farina , p. 59.

- ↑ Mönckmeier: The history of the house Johann Maria Farina , S. 60th

- ↑ p. 61.

- ↑ Quoted here from Mönckmeier: The history of the house Johann Maria Farina , p. 62.

- ↑ Mönckmeier: The history of the house Johann Maria Farina , p. 63.

- ↑ Mönckmeier: The history of the house Johann Maria Farina , p. 67.

- ↑ "You moins vous ne risquez de lui en faire du mal." Quoted here from Mönckmeier, Die Geschichte des Haus Johann Maria Farina , p. 70.

- ↑ Mönckmeier: The history of the house Johann Maria Farina , p. 81.

- ↑ Mönckmeier: The history of the house Johann Maria Farina , p. 91.

- ↑ Mönckmeier: The history of the house Johann Maria Farina , p. 92.

- ↑ So also Mönckmeier, The history of the house Johann Maria Farina , S. 93rd

- ↑ Mémoires de Constant sur la vie privée de Napoléon, sa famille et sa cour, Tome3, 1830 p. 154.

- ↑ To celebrate the company's 200 year business anniversary - Johann Maria Farina across from Jülichs-Platz , p. 21.

- ↑ Package insert from Farina for the men's fragrance "Russian Leather", August 2018

- ↑ RWWA 33/587/3 correspondence and contracts with Doetsch Grether & Cie 1927

- ↑ Pleitgen: The development of business accounting from 1890 to 1940 using the example of the companies Krupp, Scheidt and Farina , p. 95.

- ↑ RWWA 33/348/17 Trustee reports Doetsch Grether & Cie 1943

- ↑ From the ventures . In: Die Zeit , No. 46/1959, p. 27.

- ↑ Schäfke: Oh! De Cologne , pp. 44 and 46.

- ↑ Schröder: Der Markenartikel , p. 165 ff.

- ↑ RWWA 33/348/18 trust agreements Doetsch Grether & Cie 1944–1999

Coordinates: 50 ° 56 ′ 15 ″ N , 6 ° 57 ′ 29 ″ E