Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars ( Crimean Tatar qırımtatar , qırımtatarları ) are a Muslim Turkic-speaking ethnic group originally living on the Crimean peninsula . Their language belongs to the group of northwestern Turkic languages .

Crimean Tatars differ significantly from the Volga-Ural Tatars , and so they are called Crimean Turks - mainly by the Turks from Turkey ( Turkey Turks) . This takes into account the fact that their written language is derived from a regional variant of Ottoman and is therefore very close to Turkish .

history

The Crimean Tatars, Sunni since the 13th century , contributed significantly to the spread of Islam in Ukraine .

ancestry

According to one theory, the Crimean Tatars are the descendants of many of the populations who lived in or conquered the Crimea ( Mongols , Khazars , Greeks , Iranians , Huns , Bulgarians , Cumans , Crimean Goths and later Crimean Menians , Venetians and Genoese ). So their roots are formed by different ethnic groups . So are mainly Kipchaks and Tatars (Zentralkrim) Nogaier -Tataren (northern steppe) and Ottoman Turks (southern coast) counted among their ancestors. The latter assimilated numerous Venetians and Genoese; their language, a regional variant of Ottoman , was the lingua franca of Crimea between the 15th and 19th centuries and influenced the Tatar and Nogai colloquial languages .

According to another theory, the Crimean Tatars are descendants of the Kipchaks who settled in Crimea in the course of the Mongol conquests and then later founded an independent khanate after the fall of the Golden Horde .

Crimean Khanate

In the 15th century, the Mongolian Golden Horde got into internal turmoil, which resulted in several splits. Hacı I. Giray from a noble family of Genghisids founded his own khanate with the Crimea as its center around 1444 with the support of the Kingdom of Poland , the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Grand Duchy of Moscow - after he had previously tried unsuccessfully to gain power in the Golden Horde tear. The khanate, initially unstable until 1478, ruled large parts of modern Ukraine and southern Russia until 1792; among other things from 1556 the areas of the Nogaier in the north Caucasian Kuban . The capital became Bakhchysaraj , founded around 1450 , from where a Giray (كرايلر) Khan ruled for most of the time. In addition to the Giray and the Nogaiians, the Şirin, Barın, Arğın, Qıpçaq and later Mansuroğlu and Sicavut were always very influential. The Khanate of Crimea was thus less Mongolian than the Golden Horde and it was even significantly involved in their downfall in 1502. Until the Battle of Molodi (1571) it was one of the most important states in Eastern Europe. Even after that and into the 18th century it was a power factor in the region: Alliances were formed with other successor states of the Golden Horde, in particular with the khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan . In 1648 it helped the hetmanate of Ukraine to break away from Poland-Lithuania by entering into an alliance with the Zaporozhian Cossacks of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi . During the Second Northern War (1655–1660) it allied itself with Poland and helped save the country from being divided up by Russians, Swedes, Transylvanians and Brandenburgers. It operated lively trade with the Ottoman Empire, whose protectorate it enjoyed from 1478 to 1774 while maintaining a high degree of autonomy. From 1758 to 1787 the Mankite Nogai made the Khan. In the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774), the Ottomans had to recognize the independence of Crimea. From 1783 the khanate was initially under indirect and from the Treaty of Iași (1792) under direct Russian rule.

Slavery and the Crimean Khanate

Even before the formation of the Crimean Khanate, the Crimea was an important starting point for the slave trade . Building on the nomadic way of life of the Crimean Tatars, these activities made up the bulk of the Crimean Tatar economy at times. The raids into the mostly Slavic neighboring areas began in 1468 and did not end until the end of the 17th century.

The Crimean Tatars made their rich human booty with raids into the Ukraine, southern Russia and in 1656 to Masuria . Most of the men had to take part in these raids, known in Tatar as the “harvest of the steppe”. The slaves were then brought to the Crimea, bought by mostly Christian traders (Greeks, Armenians) in Kefe and from there they were sold to the Ottoman Empire or the Middle East . The most famous figure among these slaves was Roxelane , who later became the wife of Suleyman the Magnificent. The exact number of slaves is difficult to determine.

The Crimean Tatars also made great profits with ransom money from the affected countries or with tribute payments from such countries with the aim of preventing raids.

For a long time, the raids by the Crimean Tatars posed a serious problem on the khanate's Christian neighbors, both on the Russian Empire and on Poland-Lithuania , which at that time included Ukraine and Belarus. The Principality of Moldova was also affected by the raids by the Crimean Tatars. Whole areas were depopulated and looted, which weakened these states considerably. In the 16th century, Russia had to recruit up to 80,000 men every year to work on the southern fortifications ( Russian Verhaulinie ) against the lightning-fast incursions of the steppe riders, which were hardly predictable due to the thousands of kilometers of steppe border. A third of the state budget had to be raised for the defense against the Crimean Tatars.

The incursions of the Crimean Tatars were a frequent cause of war and also contributed to the development of the Cossacks as peasants who could defend themselves . As a result of the incursions, the southern steppe areas could not be fully populated until the 18th century, when the Tatar danger was eliminated ( New Russia ). Russia , strengthened under Tsar Peter the Great , pursued an active policy of repression against the Crimean Tatars.

Annexation of the Crimean Khanate and Russian rule

After Russia had conquered the Crimea in 1771, it replaced the Ottoman protectorate with its own and guaranteed the existence of the khanate as a "free, unrelated territory". After the Russian victory over the Ottomans in 1774 , the Peace of Küçük Kaynarca was followed by nine years of relative independence for the Crimean Tatars. With the withdrawal of the Ottomans, the Crimean Tatar upper class debated a new direction in their foreign policy. There were several rebellions of the extremely anti-Russian-minded Tatar population against the growing Russian influence. Catherine the Great tolerated Sahin Giray as Khan on the throne, who, however, with his pro-Russian rapprochement and reform policy, won no sympathy among the population. The Russian Empire repeatedly intervened militarily to eliminate its opponents and reinstate Sahin. There was major destruction. With the resettlement of the Greeks and Armenians living in Crimea to Russian territory, an important trade pillar in Crimean Tatar society collapsed.

Ultimately, the annexation by Russia took place on the advice and under the command of Grigory Alexandrovich Potjomkins in 1783. The khan was replaced by a Russian governor ( Taurian governorate ), the Crimean Tatar nobility ( mirza ) integrated into the administrative structure of the khanate. His land ownership and privileges were guaranteed. The Tatar farmers also kept their land. Because of this policy, there were no major uprisings against Russian rule. With the encouraged settlement of Russian and foreign settlers in the Crimea, the associated expropriation, the ousting of the nobility from the administration and the cities, Crimean Tatars were driven into emigration in larger waves (larger ones in the 1790s and 1850s). They settled in parts of what is now Romania and Bulgaria , which were then part of the Ottoman Empire. Many bathhouses, mosques, fountains and evidence of antiquity were destroyed. After the middle of the 19th century, the Crimean Tatars had become a minority in the Crimea. All important administrative tasks were taken over by Russians, the demographically and economically weakened population group of the Crimean Tatars also politically disempowered.

Short-term autonomy in the First World War

After the fall of the Tsar, the Crimean Tatars were one of the many non-Russian ethnic groups in Russia who mobilized politically and socially. In June 1917, a national party, Milli Firka , was formed, demanding territorial autonomy for the Crimean Tatars. Violent clashes broke out between the Crimean Tatar and Russian-Ukrainian populations. After the October Revolution (1917), a short-lived Crimean Tatar state called the People's Republic of Crimea was proclaimed in December in Crimea , but it existed less than a month before the Bolsheviks crushed it. The ruling class of the Crimean Tatar national movement sought support among Russia's opponents in the First World War . The Ottoman Empire wanted a Muslim Crimean state to be established under the Ottoman protectorate. Erich Ludendorff, on the other hand, preferred the establishment of a German colonial state in the Crimea, an idea that Adolf Hitler reverted to ( Gotenland ). Under the German occupation, from spring to autumn 1918, the non-Russian press banned by the Bolsheviks was re-admitted, the Simferopol University was founded, and Crimean citizenship was introduced.

In 1921 the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of Crimea was established within the RSFSR . About 15% of the Crimean Tatars died during the famine from 1921 to 1922 , triggered by a state-forced grain export. In the autonomous Soviet republic, Crimean Tatar was the official language alongside Russian and Crimean Tatar culture and language were promoted. From 1927, with the beginning of the Stalinist terror, the tide turned, Crimean Tatar cultural institutions were again banned and the traditional Arabic spelling of Crimean Tatar was replaced in quick succession by Latin and then Cyrillic . This meant the loss of access to the written tradition for future generations.

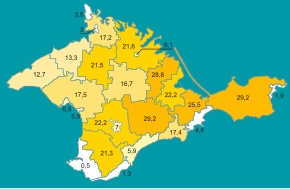

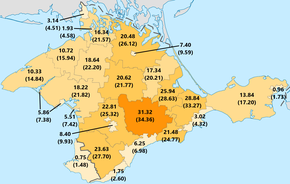

According to the first edition of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia , the population of Crimea in 1936 consisted of: Russians 43.5%; Ukrainians 10%, Jews 7.4%, Germans 5.7%, Tatars 23.1% (202,000 out of the total population of 875,100).

German occupation, collaboration and deportation in World War II

Due to the oppression they had suffered in 1941, the German occupation troops of the Second World War were received more warmly in the Crimea than in other parts of the Soviet Union . About 20,000 Crimean Tatars, i.e. about 7 percent of the entire Crimean Tatar population, made themselves available to the Wehrmacht , practically all men capable of military service, twice as many as had been drafted into the Red Army . Crimean Tatar units were used by the German security service in the rear area and to fight partisans, as well as self-protection in the villages. As an association of Crimean Tatar volunteers, the Tatar SS-Waffen Mountain Brigade No. 1 was formed in July 1944. On the initiative of the leader of Einsatzgruppe D of the security service, SS-Oberführer Otto Ohlendorf , many of the Crimean Tatars who were willing to collaborate and who were used for informing tasks in the initial phase of the occupation of Crimea were able to be won over to this troop and thus the German 11 Army to supplement. The brigade was disbanded at the end of 1944, and its final 3,500 fighters were assigned to the SS-Waffengruppe Krim.

Crimean Tatars also took part in the Soviet partisan movement. Eight Crimean Tatars were awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union , and a Crimean Tatar pilot - Amet-Chan Sultan - was awarded this prize twice.

On April 9, 1944, the Wehrmacht lost Odessa . In the Battle of the Crimea , the Red Army managed to completely retake the peninsula by May 12th.

From the southern regions of the Soviet Union, several peoples who had tried to use the war to enforce independence were deported to the Asian part of the Soviet Union during World War II. The autonomous republics of the Kalmyks, Chechens and Ingush were dissolved, including the Autonomous Soviet Republic of Crimea. All Crimean Tatars were deported to Central Asia on charges of collective collaboration . Within a few days (May 18-20, 1944) around 189,000 people were transported by train under terrible conditions. The deportees' wagons were often not opened for days, estimates of the percentage of deaths from dying of thirst, starvation and illness range between 22% and 46%.

During the following years, other non-Slavic minorities (mostly Crimean Menians , Greeks, Crimean Germans , Crimean Italians ) were driven into emigration; only Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians were encouraged to settle there.

By resolution of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on February 19, 1954 on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of the Treaty of Pereyaslav , the Crimea Oblast was transferred to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (USSR) on April 26, 1954 .

return

Of the non-Russian national movements in the Soviet Union since the 1960s, the Crimean Tatars were the earliest and most intensely politically mobilized. They campaigned for the return to their homeland and the re-establishment of their republic. In 1967 the Crimean Tatars were acquitted of the charge of collective treason by decree by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, but they were disproportionately represented among the political prisoners of the 1970s.

In 1985 Gorbachev's glasnost and perestroika began. Since 1989 they were finally allowed to return, despite the opposition of the population now living there - but not to their original settlement areas. Instead, they were distributed across the peninsula .

In 1990 there were again around 20,000 Crimean Tatars in the Crimea. Despite perestroika, they received no support from the authorities. Some of them were deported again or their makeshift houses were destroyed. Many settled without official permission.

In the second half of 1991 the Soviet Union disintegrated ; In the course of this process, Ukraine declared their independence on September 24, 1991, and Belarus the next day.

In June 1991, the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People was organized in Crimea , a council of Crimean Tatars, which is a political representative of the Crimean Tatar national movement. The current chairman is Refat Abdurachmanowitsch Tschubarow .

Minority in Ukraine

Since the end of the 1980s (as of around 2008) around 266,000 have returned from deportation. In the meantime they have peacefully achieved their political recognition, but not the legal one. Since majority voting applies in Crimea, all minorities are underrepresented in the Crimean Parliament.

In 1992, Crimean Tatar was declared the third regional official language of the peninsula, as its speakers now made up over 10 percent of the population.

The Crimean Tatars usually allied themselves with the central government of Ukraine against the Russian-oriented government of Crimea. In 1998 they lost the guarantee of a fixed number of seats in the Kiev parliament. The aim of the Crimean Tatar movement is to restore this quota, to have adequate representation in the authorities and to improve their economic and social situation. In the 1990s, their demonstrations and arguments with the law enforcement officers had a considerable potential for violence.

Since the Orange Revolution (2004), which was supported by the Crimean Tatars, the government in Kiev has occasionally supported the interests of the Crimean Tatars in Crimea (or in the local authority there ), where the majority of the population is of Russian descent.

The majority of the Crimean Tatars are Sunni . Today around 280,000 or nearly 12 percent of the Crimean's 2.5 million residents are believed to be Crimean Tatars; 150,000 Crimean Tatars still live in Uzbekistan , a large number also in the southern Russian district of Krasnodar .

As the OSCE High Commissioner for National Minorities reported in August 2013, the return of the formerly deported minorities to Crimea led to social and economic tensions. There have been cases of hate speech , devastation of religious sites, violent clashes, and widespread land occupation.

Situation in the Crimean crisis

In the Crimean crisis of 2014, the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People , a national political association of Crimean Tatars, called for a boycott of the referendum on the status of Crimea , opposing the secession of Crimea from Ukraine. The new Crimean government offered the Council of Crimean Tatars a seat in the cabinet if it recognized the new government. Milli Firka , the re-established Crimean Tatar party, said the Crimean Tatars would not heed the Mejli's call to boycott.

Since the annexation of Crimea to the Russian Federation in the spring of 2014, the Crimean Tatars have been living under Russian rule again.

A Crimean Tatar businessman's private television station, ATR, was launched in 2006 . After the annexation of the peninsula by Russia, he no longer received a broadcast license. Since then he has been broadcasting from Kiev .

The Crimean Tatars, who have fled to the western parts of the country as internally displaced persons (IDPs) due to the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine or because of the annexation of Crimea , are supported by the Lviv non-governmental organization Crimea SOS in cooperation with the United Nations refugee agency ( UNHCR ).

In April 2014, Russian President Putin passed a law on the “rehabilitation of the Crimean Tatars” who suffered under the tyranny of Stalin. Everything must be done so that the "annexation to the Russian Federation can be flanked by the restoration of the legitimate rights of the Crimean Tatar nation" - said Putin.

In 2017, however, the United Nations found that the human rights situation in Crimea had deteriorated significantly since its annexation by Russia.

The law enforcement agencies of the Russian Federation conducted criminal trials against several dozen Crimean Tatars who refused to accept their forcibly granted Russian citizenship. Participants in protests were also arrested.

society

Diaspora

The majority of the Crimean Tatars live in the diaspora in Turkey. Up to 5 million are given, which are fully integrated and closely networked through corresponding cultural associations. This also includes the descendants of the Crimean Tatars who emigrated to the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century. The focus is on the city of Eskişehir . The Crimean Tatars in Romania and Bulgaria have a similar history.

The second largest group are the descendants of the residents who were deported by Stalin to the Central Asian states, above all Uzbekistan (100,000). These make up a large proportion of the returnees.

religion

The Crimean Tatars are Sunni Muslims of Hanafi law school. Since the increasing number of expellees returned, there have been a few representative places of worship again, but the imams are mostly trained abroad, especially in Turkey, due to the lack of training opportunities.

The religious understanding is u. a. strongly dominated by İsmail Gasprinski by a secular, Reformation doctrine, which was briefly expressed in the People's Republic of Crimea as the first secular republic in the Islamic world. The later secularization of Turkey under Kemal Ataturk also had an influence here .

Lately there is said to have been an increasing number of unofficial preachers from the Arab world who preach more radical teachings, including the Hizb ut-Tahrir . However, there are no major Islamist-motivated incidents or organizations.

literature

The beginnings of Crimean Tatar literature can be found in the Dīwān literature of the Khans. The Khans Ğazı II Giray (1554–1608) and Halim Giray Han (1772–1824) are known poets. It is heavily influenced by Persian poetry.

After the Russian Revolution in 1905 , literature flourished again. A group of Crimean Tatar authors and politicians such as Hasan Sabri Ayvazov (–1936) and Ahmet Özenbaşlı (1867–1924) gathered in the Tercüman newspaper published by İsmail Gasprinski . Against the “too moderate” perceived positions, a literary counter-movement with the group of the “Genç Tatarlar” (“Young Tatars”) formed in the newspaper Vatan Hadimi .

With the complete deportation of the Crimean Tatars, the literary business came to an abrupt end. The times of deportation, exile and return were put into words by Cengiz Dağcı, who lived in exile in England . Contemporary authors also include Şakir Selim, Ablayaziz Veliyev, Rıza Fasil and Yunus Kandim.

Well-known Crimean Tatars

- İsmail Gasprinski (1851–1914), intellectual, educator, publisher and politician

- Edige Mustafa Kirimal (1911–1980), Turkish politician and representative of the Crimean Tatars in Germany

- Noman Çelebicihan , politician, President of the short-lived Republic of the Crimean Tatars

- Muazzez İlmiye Çığ (* 1914), Turkish sumerologist

- Halil İnalcık (1916–2016), Turkish historian

- Amet-Chan Sultan (1920–1971), Soviet fighter pilot

- Cüneyt Arkin (* 1937), Turkish actor and director

- Mustafa Abduldschemil Dschemilew (Qırımoğlu) (* 1943), Soviet-Ukrainian politician

- İlber Ortaylı (* 1947), Turkish historian

- Enwer Ismailow (* 1955), Ukrainian jazz guitarist

- Hasan Polatkan (1915–1961), Turkish politician

- Orhan Gencebay (* 1944), Turkish singer, saz virtuoso and actor

- Jamolidin Abdujaparov (* 1964), racing cyclist

- Emir-Ussejin Kuku (* 1976), human rights activist

- Jamala (* 1983), singer, winner of the Eurovision Song Contest 2016.

- Server Mustafayev (* 1986), human rights activist

gallery

literature

- Alan W. Fisher: The Crimean Tatars . Hoover Press, 1978, ISBN 0-8179-6662-5 .

- Alexandre Billette: The Russian Enemy . In: Le Monde diplomatique . No. 8152 , December 15, 2006, p. 23 .

- Brian Glyn Williams: The Hidden Ethnic Cleansing of Muslims in the Soviet Union. The Exile and Repatriation of the Crimean Tatars . In: Journal of Contemporary History . tape 37 , no. 3 , July 2002, ISSN 0022-0094 , p. 323-347 .

- Brian Glyn Williams: The Crimean Tatars. From Soviet Genocide to Putin's Conquest . Hurst, London 2015, ISBN 1-84904-518-6 .

- Norman M. Naimark : Flaming hatred. Ethnic cleansing in the 20th century (= Fischer. The time of National Socialism. 17890 ). Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-596-17890-2 , pp. 128-139 .

- Greta Lynn Uehling: Beyond Memory. The Crimean Tatars' Deportation and Return . Palgrave Macmillan, New York NY et al. a. 2004, ISBN 1-4039-6264-2 .

- V. Stanley Vardys: The Case of the Crimean Tartars . In: Russian Review . tape 30 , no. 2 , April 1971, ISSN 0036-0341 , p. 101-110 .

- Ulrich Hofmeister / Kerstin S. Jobst (eds.), Crimean Tatars, Austrian Journal of Historical Studies (ÖZG) / Austrian Journal of Historical Studies, 28 | 2017 / 1st study publisher. ISSN 1016-765X .

See also

Web links

- Exile order of May 11, 1944 (English, Russian )

- Tatar.Net

- Vatan KIRIM, Crimean Tatar diaspora in Turkey

- Chapter Crimean Tatars in student thesis "The National Question in the Crimea" by Veit Kühne

- Crimea: Rioting between Tatars and Russians (August 15, 2006)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Schulze: Crimean Tatar. (PDF; 192 kB), accessed on March 17, 2013.

- ^ John E. Woods, Judith Pfeiffer, Ernest Tucker: Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi . Otto Harrassowitz, January 1, 2005 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ Яворницький Д. І. Історія запорозьких козаків. У 3-х т. - Т. 1. АН Української РСР. Археографічна комісія, Інститут історії. - К .: Наукова думка, 1990. - С. 331-342

- ↑ Eizo Matsuki: The Crimean Tatars and their Russian-Captive Slaves. ( Memento from June 5, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 364 kB). Mediterranean Studies Group at Hitotsubashi University.

- ^ Alan W. Fisher: The Crimean Tatars. Hoover Press, 1978, p. 26. in Google Book Search.

- ^ Günther Stökl : Russian history. From the beginnings to the present (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 244). 4th enlarged edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-520-24404-7 , p. 421.

- ^ Alan W. Fisher: The Crimean Tatars. Hoover Press, 1978, pp. 79-90 limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ Andreas Kappeler: Russia as a multi-ethnic empire: emergence - history - decay. CH Beck, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-406-36472-1 , p. 50 Crimean Tatars in the Google book search

- ↑ Kerstin Jobst: Playing with great powers? National conflicts after the collapse of the Tsarist Empire up to the beginning of the Russian civil war in 1918/19 on the Crimean peninsula. In: Philipp Ther: The dark side of the nation states: “Ethnic cleansing” in modern Europe. Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-525-36806-0 , 83 ff.

- ↑ Akira Iriye, Jürgen Osterhammel, Emily S. Rosenberg, Charles S. Maier: Geschichte der Welt 1870-1945. World markets and world wars. Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-64105-3 , p. 559.

- ↑ Quoted here from V. Stanley Vardys, 1971.

- ^ Rolf-Dieter Müller: On the side of the Wehrmacht: Hitler's foreign helpers in the "Crusade against Bolshevism" 1941–1945. Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-86153-448-8 , p. 237.

- ↑ David Motadel : Islam and Nazi Germany's War. Harvard University Press 2014, p. 235 ff.

- ^ Isabelle Kreindler: The Soviet Deportated Nationalities: A Summary and an Update. In: Soviet Studies. Volume 38, No. 3, July 1986, p. 391; JSTOR 151700 .

- ↑ Philipp Ther: The dark side of the nation states: "Ethnic cleansing" in modern Europe. Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-525-36806-0 , p. 136.

- ^ Isabelle Kreindler: The Soviet Deportated Nationalities: A Summary and an Update. In: Soviet Studies. Volume 38, No. 3, July 1986, p. 396.

- ↑ The Transfer of the Crimea to the Ukraine (English)

- ^ Friedrich-Christian Schroeder, Herbert Küpper: The legal processing of the communist past in Eastern Europe. Frankfurt 2010, ISBN 978-3-631-59611-1 , p. 192.

- ↑ Hans-Heinrich Nolte : Little History of Russia , Reclam, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-15-009696-0 , p. 410.

- ^ Andreas Kappeler: Brief history of the Ukraine. Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-58780-1 , p. 268.

- ↑ a b Integration of formerly deported people in Crimea, Ukraine, is focus of OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities' latest report , on the OSCE report “The Integration of Formerly Deported People in Crimea, Ukraine” of August 16, 2013.

- ^ Andreas Kappeler: Brief history of the Ukraine. Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-58780-1 , pp. 268f.

- ↑ Tatars in the Crimea: leader tape or resistance. on: Spiegel Online . March 22, 2014 (a report from Bakhchisarai and Simferopol).

- ↑ Uwe Halbach: Analysis: The Crimean Tatars in the Ukraine Crisis , Federal Agency for Civic Education, November 2014

- ↑ UNHCR website with the presentation of the NGO Crimea SOS ( Memento from July 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- ↑ Путин подписал указ о реабилитации крымских татар . In: ТАСС . ( tass.ru [accessed October 27, 2017]).

- ↑ Konrad Schuller : Old Soviet Methods. FAZ from Sep 29 2017, p- 8

- ↑ Citizens of Ukraine captured in Russia. 88 cases researched by OVD-Info . In: Eastern Europe , 6/2018, pp. 3–48.

- ^ Brian Glyn Williams: The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation. Brill, 2001, p. 113.

- ↑ Ann-Dorit Boy: The fear of the Islamists. In: FAZ . March 10, 2014.