Local anesthesia (dentistry)

| Local dental anesthesia |

|---|

| MeSH D000766 |

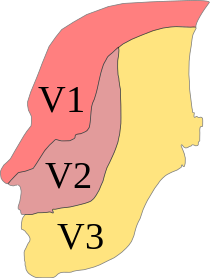

The local anesthesia ( ; Latin locus , "place", ancient Greek ἀν to "no" and αἴσθησις AISTHESIS "perception" with alpha privative , thus local insensibility , local anesthesia ) or local anesthesia - as opposed to general anesthesia (colloquially general anesthesia ) - a limited elimination of pain in the area of nerve endings or nerve conduction pathways without affecting the patient's consciousness. The most common outpatient application is local anesthesia in dentistry . Here is primarily a distinction between the infiltration anesthesia (including terminal anesthesia), the intraligamental anesthesia and regional anesthesia (including regional anesthesia). The conduction anesthesia on the lower jaw takes place in particular on the inferior alveolar nerve as part of the third branch of the trigeminal nerve , the mandibular nerve , while the conduction anesthesia on the upper jaw takes place on the maxillary nerve . The goal is to eliminate pain in all painful interventions in the field of dentistry, oral and maxillofacial medicine. Local anesthesia makes a decisive contribution to avoiding dentophobia (fear of dental treatment) and, with the appropriate painless or painless injection technique , also to avoiding trypanophobia (fear of injections). The implementation of local anesthesia is subject to the (dental) doctor's reservation .

Demarcation

With surface anesthesia , the anesthetic is usually applied to the mucous membrane, whereby the sensitive nerve endings are reached by diffusion.

The infiltration anesthesia is an encapsulation of the tooth or of the target area in the tissue with a local anesthetic . Sensitive conduction pathways , which consist of a bundle of nerve fibers , conduct the impulses from sensory receptors to the brain .

The aim of conduction anesthesia is to block a nerve pathway, whereby all areas innervated (supplied) by this nerve branch are anesthetized.

With intraligamentary anesthesia , only one tooth is specifically anesthetized.

Mode of action

Chemically, local anesthetics come in two forms. While the undissociated, lipophilic base penetrates to the nerve, the hydrophilic , dissociated form ( cation ) has a local effect. It blocks the influx of sodium into (nerve) cells and thus the conduction of stimuli . The thicker the nerve fiber, the higher the concentration of the local anesthetic must be. Due to the small diameter of the pain-conducting C and A-delta fibers, they are inhibited early on, while the motor A-alpha fibers are not tied off until late.

Surface anesthesia

Surface anesthesia is used in the oral cavity to eliminate pain in the oral mucosa , for example to reduce the pain of the puncture pain of the subsequent local anesthesia or for superficial surgery on the gums . Mainly articaine in 2 to 4 percent concentration, lidocaine or tetracaine in 0.5 to 3 percent concentration are used. The surface anesthetics are available as a gel, ointment or spray. For better precise application, the anesthetic is usually applied to a cotton or foam pellet , which is pressed onto the area to be anesthetized for about a minute. The ethanol content can also disinfect the injection site. Surface anesthesia is also used in sensitive patients to switch off the gag reflex or swallow reflex , for example when taking an impression or taking X-rays in the oral cavity. The surface anesthetic is applied to the soft palate and the base of the tongue. A 0.5 to 1 percent solution is used here. Exceeding the limit dose must be avoided. In addition, the surface can also be anesthetized by infiltrating the tissue (skin wheals), also as part of segment therapy .

Pressure anesthesia can also reduce or avoid the pain of the puncture. Pressure is applied to the intended injection area for about 15 seconds with a finger or an instrument.

Taking away the fear of the injection from the patient also means taking away the fear of the treatment, because under local anesthesia it is painless or painless. Most of the time, the phobia of syringes arose from bad previous experiences, mainly in childhood. A clearly perceptible empathy of the treating dentist contributes to the reduction of the fear of needles.

An anesthetic gel is used in adults and is suitable for professional tooth cleaning (PZR) in pain-sensitive patients. It can also be used for minor periodontal surgery. It is applied into the sulcus of each tooth to be treated with the help of a blunt needle and consists of equal parts lidocaine and prilocaine (Oraqix) in a concentration of 5 percent .

Instruments

As a rule, the anesthetic for infiltration anesthesia or block anesthesia is administered with a cylinder ampoule syringe , also known as a carpule syringe . However, disposable syringes are also used, with which the anesthetic is drawn from ampoules or vials . After each patient, the needles are disposed of in a cannula disposal box and the syringe set is sterilized . Partially used cylinder ampoules must not be used for other patients. More expensive self-aspirating disposable syringes with a built-in aspiration mechanism are also commercially available, as are self-aspirating cylinder ampoule syringe sets (example: Aspiject according to Evers). Aspiration ( see below ) and injection take place in the same direction using piston pressure, without the need for an aspiration pull. Cannulas according to ISO 7864 or DIN 13097 with a gauge size 25 (ø 0.5 mm) or 27 (ø 0.4 mm) and a length of 1 "(25 mm) for infiltration anesthesia or 1½" (40 mm) are used in conduction anesthesia. In the case of disposable syringes, the cannula is connected to the syringe by means of a conical Luer connector , in the case of cylindrical ampoule syringes by means of a screw connection.

Pain-free injection technique

A pain-reduced or pain-free injection can be achieved by following several measures. This includes using a surface anesthetic or applying pressure anesthesia prior to the actual injection. The local anesthetic should be warmed to body heat (37 ° C). Disposable syringes can be handled more sensitively than cylinder ampoule syringes. Because of their small size, single-use syringes appear less “threatening” to the patient. The injection cannulas should have a triple facet cut to reduce initial pain and be silicone-coated for pain-reduced gliding through the tissue . The injection cannulas lose their pain-reducing sharpness after a first injection, so that a new cannula should be used for each further injection in the same patient. Withdrawing the injection needle after bone contact avoids a painful subperiosteal injection. The injection speed should not exceed 1 ml / min. Otherwise, the sudden increase in pressure in the tissue will cause pain. Alternatively, a fractional (split) injection technique can be used, in which a small depot of the anesthetic is first applied. The injection into the tissue takes place shortly afterwards, when the first depot has already anesthetized the injection area. In addition to the aspiration test, the fractional injection can help prevent an intravascular injection of the total dose, which is particularly useful in patients with cardiovascular diseases . In this case, the first depot would lead to an increase in heart rate. Excessive bone contact leads to the tip of the needle bending over, which acts like a small barb when the cannula is pulled out after the injection and painfully tears the tissue.

Aspiration test

Before the actual injection, an aspiration test (sucking in the tissue fluid) ensures that the cannula tip does not lie in a blood vessel and that the injection is not carried out directly into a vessel (especially in the area of the inferior alveolar artery , which is immediately next to the inferior alveolar nerve lies). If the tip of the cannula were in a blood vessel, this would be visible through the sucked blood in the glass cylinder ampoule or syringe. In this case, the injection is stopped and the syringe set is exchanged and a new injection - including a new aspiration test - carried out. However, the aspiration test does not completely rule out intravascular injection. An intravascular injection leads, on the one hand, to failure of anesthesia and , on the other hand, to undesirable effects on the heart and circulation, also due to the vasoconstrictor contained in the anesthetic solution ( adrenaline , noradrenaline ).

Anesthesia in the upper jaw

Infiltration anesthesia

In the case of dental interventions in the upper jaw, infiltration anesthesia is usually performed. The puncture is made in the envelope fold in the oral vestibule at the level of the root tip. The anesthetic is under the mucosa (submucosal) and the periosteum (supraperiostal) injected so that it spreads in the bone and diffuses through it. The jawbone has a vestibular thickness of about 1–3 mm. The anesthesia usually starts to work after one to three minutes and reaches its maximum depth of effect after 20 minutes. This is sufficient, for example, to pull a tooth painlessly (extraction).

Conduction anesthesia

The greater palatine nerve supplies the dorsal (posterior) two thirds of the palatal mucosa. It can be turned off by anesthesia on the greater palatine foramen, a small opening through which the nerve passes. For this, 0.2–0.3 ml of anesthetic is sufficient. In oral surgery, in addition to vestibular infiltration anesthesia, the oral mucosa of the palate is anesthetized with a second puncture. For the posterior region ( teeth 4 to 8 ), this incision is made on the palate at the level of the upper first molar , about 1 cm from the tooth neck .

In rare cases, additional anesthesia of the nasopalatine nerve, which supplies the front third of the palatal mucosa, is necessary. For this purpose, about 0.2 ml of anesthetic is injected at the edge of the papilla incisiva . For the front teeth ( teeth 13 to 23 ), the palatal puncture is made close to the papilla, but not directly into it, as it is very sensitive to pain. As an alternative to conduction anesthesia of the incisive nerve, local anesthesia can be performed as an infiltration anesthesia through a puncture directly in the palate area of the tooth to be treated.

The figure shows a faulty and painful conduction anesthesia directly in the incisive papilla. The anesthesia was administered with excessive pressure, which can be recognized by the pale color of the papilla. In addition, too much anesthetic was injected, which caused the papilla to swell disproportionately. This injection technique with palatal local anesthesia can lead to necrosis of the palatal mucosa. In addition, a cannula that was too thick was used, which increases the pain. Kinking the injection cannula at the cannula hub creates an unnecessary risk of the cannula breaking.

Anesthesia in the lower jaw

Conduction anesthesia on the mandible foramen

In the case of dental interventions in the lower jaw, conduction anesthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve on the mandibular foramen , which lies on the inside on the ascending branch of the lower jaw bone, is placed. The difficulty with conduction anesthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve is that the point of injection, the mandibular foramen, cannot be clinically palpated or precisely localized in any other way. The guidance of the cannula is therefore based on palpable anatomical structures. The puncture site is on the side of the pterygomandibular plica (wing-mandibular fold), roughly in the middle between the rows of teeth in the upper and lower jaw. The cannula is inserted about 1 to 2 cm deep until it makes contact with the bone. The bone contact itself is painless with the appropriate injection technique. The tip of the cannula is on the inside of the mandibular branch, above the mandibular foramen in the pterygomandibular space. If the cannula is positioned exactly, it is pulled back a little after bone contact to avoid an injection under the periosteum, and then the injection is carried out.

Further conduction anesthesia

By placing another small depot of about 0.3 ml of the anesthetic, the lingual nerve is anesthetized at a distance of about 10 mm from the bone on the ascending branch of the lower jaw . For anesthesia of the buccal nerve , 0.3 ml of the anesthetic is injected into the vestibular fold of the oral vestibular area of the tooth to be treated or at the medial edge of the ascending branch of the lower jaw. To eliminate the anastomoses , the mental nerve at the mental foramen is anesthetized if necessary .

Infiltration anesthesia

Infiltration anesthesia are used in the lower jaw, especially in the anterior region . In the posterior region, infiltration anesthesia is usually insufficient because of the thickness of the bone, as the anesthetic cannot reach the inferior alveolar nerve. However, it is used for procedures that only affect the gingiva .

Intraligamentary anesthesia

Another way of anesthesia is the Intraligamentary anesthesia (ILA, Engl .: PDL injection (periodontal ligament injection), Intraligamentary anesthesia ), which is suitable for both mandibular and maxillary teeth, but with certain restrictions for the mandibular teeth. "Intraligamentary" means that a mini-cannula is inserted into the periodontal gap, into the ligaments of the tooth holding apparatus , the Sharpey fibers . There the anesthetic is injected with a particularly thin (ø 0.3 mm, gauge size G 30), short (12 mm) and pointed cannula. The injection is carried out at low pressure using a special syringe ( e.g. Citoject ), which looks like a fountain pen, into the periodontal gap of each tooth root. The local anesthetic must be dispensed drop by drop. The local anesthetic must be dispensed continuously and dropwise with a volume of 0.1 ml over a period of at least ten seconds. This very slow application of the anesthetic ensures that the tissue surrounding the tooth has the opportunity to absorb the applied anesthetic so that there is no depot in the periodontal tissue. More recent developments are the dosing wheel syringes according to DIN standard 13989: 2013 ( e.g. Soft-Ject , HSW HENKE-JECT , HSA 855-00 Hammacher ), as well as the electronically controlled STA system ( English Single tooth anesthesia , The Wand ). The anesthetic solution penetrates the tooth-holding apparatus, including the bony alveolus, to the tip of the tooth, where it numbs the nerve fibers entering the pulp within a few seconds . In the case of intraligamentary anesthesia, little anesthetic is administered per tooth, which can be particularly advantageous for patients with cardiovascular risk. With the appropriate technique, the injection pain is less than with other local anesthetic methods. The duration of action is about 20 to 30 minutes. If necessary, you can re-inject. The technique of intraligamentary anesthesia can also be helpful in the case of trypanophobia (fear of injections) in the patient. In addition, intraligamentary anesthesia enables targeted differential diagnosis in the case of pulpic complaints, if the guilty tooth cannot be identified by any other means. ILA is contraindicated in patients at risk of endocarditis , as it can spread germs from the periodontal gap. According to BGB § 670 e Patient Rights Act, a dentist's duty to provide information is also to offer the patient equivalent alternatives to conventional local anesthetic procedures and to inform them about them. In patients with hemorrhagic diathesis and under anticoagulant therapy , for example, conduction anesthesia is contraindicated, as this can have life-threatening consequences due to the risk of massive hematoma formation .

Conduction anesthesia in the mouth area

The following conduction anesthesia (also combined) may be necessary depending on the procedure in order to achieve adequate anesthesia.

| nerve | Anesthetized area |

|---|---|

| Conduction anesthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve (V3) | Bones, mucous membrane and teeth of one half of the lower jaw |

| Extraoral conduction anesthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve (V3) | dto. |

| Circuit anesthesia of the lingual nerve (V3) | Front two-thirds of one half of the tongue |

| Conduction anesthesia of the buccal nerve (V3) | Mucous membrane of the cheek |

| Conduction anesthesia of the mental nerve (V3) | Mucous membrane, skin and muscle in the chin area on one side |

| Extraoral anesthesia of the mental nerve (V3) | dto. |

| Conduction anesthesia of the greater palatine nerve (V2) | posterior two thirds of the palatal mucosa on one side and the gums of the maxillary posterior teeth |

| Conduction anesthesia of the nasopalatine nerve (incisive nerve) (V2) | anterior third of the palatal mucosa on one side |

| Conduction anesthesia of the maxillary nerve (V2) | one upper half of the jaw |

| Extraoral conduction anesthesia of the infraorbital nerve (V2) | via the rami alveolares, all teeth on one half of the upper jaw and the skin on the front and upper half of the face |

| Conduction anesthesia of the facial nerve (VII) | over sensitive fibers molars of one half of the lower jaw |

CCLADS

In 1997 a computer-controlled local anesthetic delivery system (CCLADS) was developed (known under the trade name The Wand ). This allows several injection techniques to be used:

- Anterior middle superior alveolar nerve block (AMSA), for local anesthesia of the maxillary teeth 15 to 25 .

- Palatinal anterior superior alveolar nerve block (PASA), for local anesthesia of the maxillary teeth 13 to 23 .

- Crestal intraosseous approach (CIA), for local anesthesia by injection into the bone.

Further developments led to single-tooth anesthesia ( SingleTooth-Anesthesia-System , STA) and intraligamentary anesthesia.

The principle of operation is that the anesthetic flows from the device through a thin tube to the tip of the needle, which is attached to a pencil-like holder. The anesthetic flows ahead of the needle tip. The needle tip penetrates tissue that has already been numbed and does not cause any pain during the insertion of the injection needle. Slow-flow mode is used for these anesthetic techniques, in which the device delivers 0.005 ml of anesthetic per second. Clinically, this corresponds to about one drop per 2 seconds, which corresponds to the maximum absorption rate in cancellous bone . These techniques take advantage of the porosity of the bone in the upper and lower jaw. The anesthetic is released drop by drop, diffuses through the bone and thus directly reaches the nerve at the apex of the tooth. The advantage is that there is no collateral numbness of the cheeks, tongue and lips after an injection.

The fast flow mode is used in conventional infiltration anesthesia and in conduction anesthesia. The contents of one ampoule (1.7–2 ml) can be applied in 45 seconds.

In all methods, the electronics control both the pressure and the flow rate of the anesthetic applied, so that the release into the tissue is barely perceived.

TENS

The transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is the application of electrical stimulation , which in dentistry in addition to the treatment of pain and for analgesia , such as the case of smaller interference caries therapy is used. As mechanisms, pain- relieving messenger substances ( neurotransmitters ) and endorphins as well as enkephalins should be released to an increased extent. Blood flow-enhancing, vasodilator substances such as vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP hormone) are increasingly formed, which blocks the transmission of pain impulses. The transmission of impulses to peripheral (outside the spinal cord and brain) nerves is blocked by electrical inhibitory processes.

The battery-operated TENS therapy device consists of a generator and two electrodes . The electrodes are placed intraorally (in the mouth) or extraorally (outside the mouth). The pulse strength , frequency and current strength are set by the dentist in advance, but can be changed by the patient using a hand controller depending on the pain intensity.

Nasal spray K305

The combination of the local anesthetic tetracaine- HCl (30 mg / ml) with the vasoconstrictor oxymetazoline- HCl (0.5 mg / ml) as a nasal spray causes local anesthesia in the upper jaw during minor operations. In the USA, such a preparation is approved by the FDA under the name Kovanaze for patients weighing 40 kg or more . This form of local anesthesia can preferably be used both in people with trypanophobia and in children. The side effects of the spray may temporarily result in a runny or blocked nose, sore throat, headache and watery eyes.

Addition of a vasoconstrictor

The addition of a vasoconstrictor (for vasoconstriction) has an antagonistic effect on vasodilation (vasodilation) of the local anesthetic. The blood vessels in the effective area constrict and blood flow is reduced. This slows down the removal of the local anesthetic itself and extends its duration of action. In addition, this leads to a blood depletion in the operating area and thus provides a better overview for the surgeon during surgical interventions. The combination of procaine and adrenaline was praised by Heinrich Braun in 1905 as a milestone in medical progress.

Patient classification

The patients are divided into risk classes according to the ASA classification . The in May 1941 by Meyer Saklad et al. The scheme proposed by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) under the title Grading of Patients for Surgical Procedures differentiates patients prior to anesthesia on the basis of systemic diseases. Of the six groups, only the first three groups are relevant for outpatient dental treatment. Groups four to six describe cases that require inpatient treatment.

- ASA 1: Normal, healthy patient

- ASA 2: patient with mild general disease

- ASA 3: patient with severe general illness

In addition to those grouped in the ASA classification with ASA 3 and higher, pregnant women, children and patients over 65 years of age are considered to be high-risk patients with local dental anesthesia. In particular, the concentration of the vasoconstrictor should be selected depending on the ASA grade and the likely duration of the procedure. However, the classification is controversial because of unclear definitions, even after various modifications.

adrenaline

With a catecholamine addition> 1: 100,000, the limit dose is determined by the vasoconstrictor rather than the local anesthetic substance. In this case, the maximum dose of adrenaline (epinephrine) limits the amount of local anesthetic to be administered per treatment session in a 70 kg person to 20 ml. In patients with cardiovascular diseases, the maximum dose is 40 micrograms, which corresponds to 8 ml of the solution 1: 200,000 (4th Carpules). With regard to the maximum dose, the addition of adrenaline in retraction cords , which are used to stop bleeding after the preparation of teeth for dentures, must be taken into account .

For children up to 2 years of age, the maximum daily dose of an anesthetic containing adrenaline (1: 200,000) is 2 ml, up to 4 years of age 4 ml, and up to 12 years of age 6 ml.

Norepinephrine

Norepinephrine (norepinephrine) has a significantly higher rate of undesirable side effects , such as headaches, a sharp increase in blood pressure and bradycardia . The rate of side effects of noradrenaline to adrenaline is 9: 1. Adrenaline has therefore largely replaced noradrenaline as a vasoconstrictor.

Others

Felypressin (octapressin) is a synthetic vasoconstrictor, chemically related to vasopressin , with the same functionality as epinephrine or norepinephrine, but with less effect and has therefore lost its importance. As a labor-inducing agent, it is contraindicated in pregnancy . It is the prilocaine 0.03 IE added (Xylonest) .

Duration of action

Circuit anesthesia lasts for different lengths of time, depending on the local anesthetic used, its concentration and the amount of vasoconstrictor added (adrenaline or noradrenaline). The local anesthetics articaine and lidocaine are mainly used.

Example Articain:

- 2% without vasoconstrictor: effective duration of action approx. 20 minutes

- 4% with vasoconstrictor adrenaline 1: 200,000: duration of action ready for action approx. 45 minutes

- 4% with vasoconstrictor adrenaline 1: 100,000: duration of action ready for action approx. 75 minutes

In contrast, a subjective feeling of numbness can last two to three hours. In the case of surgical interventions, the aim is to have an effect that extends beyond the intervention in order to avoid immediate postoperative pain. Local anesthesia can be repeated if the procedure takes longer. Adults can receive up to 7 mg articaine per kg body weight during one treatment. Under aspiration control, amounts of up to 500 mg (corresponds to 12.5 ml injection solution, or 7–8 carpules of the 4 percent solution) were well tolerated in healthy adults.

The flooding time of the Articaine can take up to 13 minutes individually before a sufficient depth of anesthesia is achieved.

Bupivacaine (e.g. carbostesin) is one of the most effective preparations; it is used in dentistry as part of particularly long-term treatments, for therapeutic nerve blocks and in pain therapy. It is commercially available in 0.25 and 0.5% solutions. The onset of action takes place with a delay. In contrast, the duration of action is on average up to five hours in the upper jaw and up to eight hours in the lower jaw. The addition of a vasoconstrictor does not extend the duration of action.

Phentolamine mesilate is able to reduce the duration of action by half and thus reduce the numbness of the local anesthetic in dental applications. It has been approved in Germany since the beginning of 2011 and has been available in Germany under the trade name OraVerse since 2013 and as Regitin in Switzerland . One cartridge contains 400 μg phentolamine mesilate. It is applied in the same way as the anesthetic itself. The injection is painless because the local anesthetic is still effective.

Frequency of application

In Germany, local dental anesthesia is performed on an outpatient basis around 57 million times a year, around 51.6 million of which are performed on statutory health insurance patients. In contrast, around 7.5 million local anesthesia are performed on an outpatient basis in all other medical specialties .

Rare uses

Tuber anesthesia (on the maxillary tuberosity , tuber maxillae ), cranial base anesthesia, percutaneous conduction anesthesia in the face, extraoral conduction anesthesia, intraosseous anesthesia, intraseptal anesthesia or the deactivation of the infraorbital nerve are only carried out in rare exceptional cases . The cold anesthesia is rarely used because of the mucous membrane damaging effect. Central anesthesia of the trigeminal nerve through a blockade at the Gasseri ganglion (semilunar ganglion) is only performed in the case of painful conditions that are difficult to control in trigeminal neuralgia . It is usually done by the neurosurgeon under radiological control.

Gow Gates Technique

The Gow-Gates technique (named after the first person to describe it, the Australian George Gow-Gates ) was developed in 1973 to reduce the failure rate of conduction anesthesia to only 5%. A single injection is used to carry out several conduction anesthesia, namely the inferior alveolar nerve, the lingual nerve, the mylohyoid nerve , the auriculotemporal nerve and - with 75 percent effectiveness - also the buccal nerve . For this purpose, a depot of the local anesthetic is placed on the condylar neck of the lower jaw. With the mouth wide open, the condyle head is palpated at the inttragic incisura and serves as a "target mark". Two-thirds of the injection needle (gauge size 27) is inserted into the fold behind the maxillary tuberosity in the paratubar space and the bone contact on the condylar neck is sought. The nerve cord itself lies distal to the condyle. After the aspiration test and the injection, the patient should keep his mouth wide open for another minute. Because of the low vascular supply of this area and the slowed removal of the local anesthetic as a result, a local anesthetic ( mepivacaine - scandicain, meaverin) without a vasoconstrictor is used. The injection is barely noticeable to the patient. The patient should be informed beforehand that with Gow-Gates local anesthesia one half of the face will be more or less completely anesthetized.

The inttragic incisura lies between the tragus and antitragus

Laguardia's method and the Vazirfani-Akinosi block

The Laguardia conduction anesthesia and the Vazirfani-Akinosi block were developed to enable the necessary performance anesthesia of the mandibular nerve when the mouth is obstructed and to avoid extraoral conduction anesthesia. With the patient's teeth closed, the injection cannula is pushed along the upper molars into the pterygomandibular space and the local anesthetic is injected.

Intrapulpal anesthesia

The injection of approx. 0.2-0.3 ml of anesthetic solution, carried out directly into the opened pulp, is carried out in addition to the usual local anesthesia if endodontic treatments (root canal treatments) cannot adequately eliminate pain.

Extraoral conduction anesthesia

If the mouth opening is severely restricted and the anesthesia techniques mentioned cannot be carried out, extraoral conduction anesthesia is used in rare cases.

Inferior alveolar nerve

For extraoral conduction anesthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve, the puncture site is sought two centimeters in front of the angle of the jaw, medial to the mandible branch. The injection cannula is advanced vertically along the lower jaw bone to the lingula mandibulae (bone tongue on the inside of the lower jaw branch that covers the foramen mandibulae).

Mental nerve

In also very rare cases, extraoral conduction anesthesia of the mental nerve can be performed. To do this, locate the puncture site three centimeters below the corner of the mouth. The injection cannula is inserted vertically up to the bone contact.

Infraorbital nerve

In the extraoral technique for conduction anesthesia of the infraorbital nerve, the area of the infraorbital foramen is marked from outside by palpation with the index finger of the left hand and the cannula is pierced below the marking finger through the skin in the direction of the infraorbital foramen. Injection into the infraorbital canal should be avoided, as otherwise nerve damage with long-term symptoms cannot be ruled out.

Failed anesthesia

As anesthesia failure is called local anesthesia, or only partially whose effects.

Local anesthesia in the inflamed area

Inflammations or infections on the tooth to be anesthetized can lead to a weakening of the anesthetic effect (and to the spread of germs into the surrounding tissue) due to the resulting drop in pH . A diffusion of the anesthetic in the nerve fibers can only by the undissociated (not in ion cleaved) Base effected. The normally slightly basic pH value of the tissue drops due to inflammation (pH ≤ 6.0), which can reduce the diffusivity due to the associated lower base content and thus the effect of the local anesthetic (to the point of ineffectiveness).

Anatomical causes

Due to the high density of vessels in the head and neck area, partial or complete intravascular injection of the anesthetic can occur, even if the aspiration test is negative, so that it cannot develop its effect in the injection area. This affects about 20% of all local anesthesia in the mouth area. The high density of vessels can lead to a rapid removal of the anesthetic, which can reduce the effect or the duration of the effect.

The injection point in conduction anesthesia of the mandibular nerve, especially the inferior alveolar nerve, the mandibular foramen, is clinically neither palpable nor can it be precisely localized in any other way and at the same time is subject to anatomical diversity. The mandible foramen lies further back in children, for example, and further forward in full denture wearers, which is part of general dental knowledge. Nevertheless, anesthesia failure can occur if the mandibular foramen deviates from the usual position.

There may be an accessory innervation, for example through the mylohyoid nerves .

Incorrect injection technique

Anesthesia to a failure in the management of anesthesia of the mandibular nerve, it can also be caused by a faulty injection technique in the medial pterygoid muscle , in the plexus venosus pterygoideus or in the parotid come.

Diagnostic local anesthesia

Local anesthesia is used to contain toothache when the tooth causing the pain cannot be identified by other methods. For this purpose, individual teeth are specifically anesthetized and the causer is searched for in a process of elimination.

Therapeutic local anesthesia

Therapeutic local anesthesia is used to treat atypical odontalgia ( atypical toothache , see also atypical facial pain ). 1.7 ml of the local anesthetic articain without a vasoconstrictor are injected into the pain site once or on two consecutive days. It is also used in neural therapy in the form of therapeutic anesthesia . In some of the patients a pain relief is achieved that lasts well beyond the duration of the anesthesia and ideally leads to the complete disappearance of the symptoms.

Local preventive anesthesia

During chemotherapy in oncology , several local anesthesia with vasoconstrictor in the mouth / jaw area are administered to prevent pronounced mucositis , which reduces the flooding of the chemotherapeutic agent into the mucous membrane. In addition, a thirty-minute cold therapy by sucking ice cubes before the radiation therapy can increase the local vasoconstriction during radiation therapy. The resulting insufficient supply of oxygen to the tissue reduces the cellular sensitivity to radiation .

Contraindications

For the purposes of the vasoconstrictor epinephrine as absolute contraindications , the narrow-angle glaucoma , the high-frequency continuous arrhythmia and taking tricyclic antidepressants . The latter increase the adrenaline effect three times.

In cocaine abusus, no (nor-) adrenaline must be added to the local anesthetic, as cocaine inhibits the breakdown of these substances and life-threatening high pressure crises can occur.

unwanted effects

Intravascular injection

If too large a quantity of the substance used gets into the circulatory system, for example in the case of an intravenous injection unnoticed, this can lead to undesirable effects. These show up in restlessness, dizziness, palpitations, oral tingling, metallic taste in the mouth or numbness up to generalized seizures.

Allergic reaction

In the case of local anesthetics of the amide type , mainly allergic reactions to certain stabilizers that were added to the preparations, such as methyl paraben or sodium thiosulfate , which serve as preservatives , were observed . Newer local anesthetics of the amide type are made paraben-free. Allergies occur primarily with local anesthetics of the ester type ( procaine - novocaine ), as the breakdown of these substances produces paraaminobenzoic acid , which is held responsible for the allergic reaction. Local anesthetics of the ester type are rarely used,

Alveolitis sicca

The real wound healing after tooth extraction takes place as primary healing . The alveolus (tooth socket) bleeds completely, a coagulum (blood clot) forms in the alveolus, which after a few days is supplied with blood by spouting capillaries and turns into a scar tissue via a granulation tissue , which later forms bones again. If the bleeding from the extraction wound is very weak - the vasoconstrictor additive in the local anesthetic may be responsible for this - no coagulum may form at all and the bone is exposed, exposing it to oral germs and contamination with bacteria . The result is a painful wound healing disorder, alveolitis sicca (synonyms: dry alveolus, alveolitis sicca dolorosa, Dolor post extractionem or dry socket), a special form of osteitis (bone inflammation).

Local anesthesia for ADHD

In attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) there may be deviations in the effect of local anesthetics. The interactions of methylphenidate hydrochloride ( Ritalin ), the primary drug used in these patients that is a selective norepinephrine / dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI) , limit drug choices . Drug therapy can also be carried out with atomoxetine ( Strattera ), a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, or individually formulated amphetamines that influence norepinephrine / dopamine release. The interactions are the subject of research. All preparations are sympathomimetics , which means an increase in blood pressure and heart rate and bronchodilation . The use of vasoconstrictors in local anesthesia should therefore be carried out with caution, i.e. in low doses (max. 1 mg / kg body weight, max. 40 mg). As already mentioned, the maximum daily dose of an anesthetic containing adrenaline (1: 200,000) for children up to 2 years of age is 2 ml, up to 4 years of age 4 ml, and up to 12 years of age 6 ml of the anesthetic solution. The use of intraligamentary anesthesia should be preferred, if possible. An outpatient clinic for adults with ADHD reported that around 10–20% of those affected reported noticeably longer (approx. 24 hours) or (more often) significantly reduced and weakened effects of local anesthesia during dental treatment.

Complications

In addition to the systemic undesirable effects (for example from an intravascular injection), various complications can arise due to the technique of administering local anesthesia. In most cases these are reversible and therefore have no consequences. Nerve damage can occur, especially the lingual and inferior alveolar nerves. These are usually irreversible and require information . Vascular damage and tissue damage to the mucous membrane can also occur. Hematomas (bruises) can occur when blood vessels open. In very rare cases, infection ( injection abscess ) or a jaw clamp occurs . The injection cannula is extremely rarely broken, which in the worst case can lead to aspiration or swallowing. In the event of (even suspected) aspiration or swallowing of the cannula fragment, an emergency medical transport for inpatient treatment or monitoring is necessary.

Needlestick injuries

Dentists suffer an average of three percutaneous injuries per year in their professional activity , the most common being a needlestick injury when performing local anesthesia. A wide variety of infectious pathogens can be transmitted in needle stick injuries, especially the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as well as the hepatitis virus B (HBV) and hepatitis virus C (HCV). Overall, the number of needlestick injuries in the healthcare system in Germany was estimated at around 500,000 in 2002. Every year around 500 people across Germany develop hepatitis B through percutaneous injuries in their work. In 2007, the German statutory accident insurance recorded 3,959 reportable accidents at work caused by “stabbing and cutting medical tools”. Since then the curve has been going down sharply. In the current reporting year 2014, 1,162 comparable cases were reported.

statistics

Statistics from the professional association for health and welfare services on cases of incapacity for work (AUF) in the field of dentistry after needlestick injuries in which HIV or hepatitis post-exposure prophylaxis was carried out on the insured:

| year | ON* |

|---|---|

| 2015 | 80 |

| 2014 | 81 |

| 2013 | 69 |

| 2012 | 58 |

| 2011 | 59 |

| 2010 | 59 |

| 2009 | 44 |

| 2008 | 52 |

| 2007 | 38 |

* OPEN = cases with incapacity for work

Vaccinations

Hepatitis A vaccines and hepatitis B vaccines are recommended to prevent infection. There is currently no vaccine against hepatitis C. Immunity for the hepatitis B vaccine lasts about 25 years. Vaccination every five years is recommended in the UK for occupationally exposed persons. Hepatitis A vaccines are on the World Health Organization's list of essential drugs and are also part of multiple vaccines in combination with hepatitis B vaccines.

Biological Agents Ordinance

At the end of July 2013, a new version of the Biological Agents Ordinance (BioStoffV) came into force. Above all, employees in the health service should be better protected against the risk of infection from stab wounds and cuts. According to § 10 BioStoffV , used pointed and sharp work equipment, including injection needles or scalpels, must be disposed of safely. The reason for the new version was the necessary implementation of the EU needle stick directive from 2010 in national law. In detail, the regulation provides:

- Establish and use safe procedures for handling and disposing of sharp medical instruments and contaminated waste

- Introduction of appropriate disposal procedures as well as clearly marked and technically safe containers for the disposal of sharp / pointed medical instruments and injection devices

- Avoidance or restriction of the unnecessary use of sharp / pointed instruments

- Provision and use of medical instruments with integrated security and protection mechanisms

- Prohibition of putting the protective cap back on the used injection needle ( recapping )

Recapping

The " Technical Rules for Biological Agents " (TRBA 250), which are published by the Committee for Biological Agents (ABAS) in the Joint Ministerial Gazette, explicitly describe one-handed recapping as a safe tool for dentistry in the field of local anesthesia under point 4.2.5 within the meaning of TRBA 250. One-handed recapping is therefore permitted in dental practices in Germany. This means that after the injection, the injection needle can be reinserted into the protective cover with one hand, provided the other hand is not in the vicinity of the protective cover. For example, a protective cap holder can be used to ensure a safe distance when recapping. Injection cannulas are screwed onto the cylinder ampoule syringe so that they cannot simply be disposed of, but have to be unscrewed from the syringe set. Injection cannulas must also not be bent or kinked, unless this manipulation is used to activate an integrated protective device.

Recapping has been prohibited in Austria since May 2013 in accordance with the Needle Stitch Ordinance (NastV) § 4 Paragraph 2, No. 2.

To avoid needlestick injuries, a system (VarioSafe) was specially developed for the cylinder ampoule holder, in which a plastic cover can be pushed over the cannula with one hand after the injection and locked in two positions. The first and reversible lock is used for storage between the individual injections and the second for safe disposal.

Educating the patient

Local anesthesia already requires compliance with the obligation to provide medical information in accordance with Section 630e BGB .

“The treating person is obliged to inform the patient about all of the circumstances that are essential for the consent. This includes in particular the type, scope, implementation, expected consequences and risks of the measure, as well as its necessity, urgency, suitability and prospects of success with regard to the diagnosis or therapy. When providing information, it is also necessary to point out alternatives to the measure if several medically equally indicated and common methods can lead to significantly different burdens, risks or chances of recovery. "

Furthermore, it is stipulated that the information must be given orally, personally and in good time before an intervention so that the patient can sufficiently reflect on his decision. With regard to local anesthesia, this includes information about the alternatives, possible nerve damage or the risk of bite injuries during the duration of the action. The clarification is to be documented. In contrast to previous opinion, a limited ability to drive cannot be attributed to the local anesthetic alone.

The Hamm Higher Regional Court ruled on April 19, 2016 that a dentist can be liable for treatment using infiltration or conduction anesthesia if he has not informed the patient about the possible alternative treatment using intraligamentary anesthesia and that of the patient for the dental procedure given consent ( informed consent ) was therefore ineffective. It sentenced the dentist to pay € 4,000 in compensation for pain and suffering.

History of local anesthesia in dentistry

After the ophthalmologist Carl Koller (1857–1944) recognized in 1884 that cocaine numbs the tongue when tasted, the surgeon William Stewart Halsted (1852–1922) first used cocaine in dentistry in 1885 . After initial animal experiments, he used the method of numbing the mandibular nerve as a conduction anesthetic. In addition to surface and conduction anesthesia, infiltration anesthesia developed from this. In 1905, the Leipzig surgeon Heinrich Braun extended the duration and depth of action of the procaine developed by Alfred Einhorn , which assigned the name novocaine to the active ingredient , by adding adrenaline. In 1905 , the chemist Friedrich Stolz from Heilbronn succeeded in artificially producing the hormone Suprarenin on behalf of Hoechst . In 1920, the dentist and anatomist Harry Safe described in his textbook “Anatomy and technology of central anesthesia in the oral cavity” the exact procedure for performing the various local anesthesia in the oral cavity. Lidocaine was the first amino - amide -Lokalanästhetikum represented by the Swedish chemist Nils Löfgren (1913-1967) and Bengt Lundqvist was synthesized (1922-1953) in the year 1943rd They sold the patent rights of lidocaine to the Swedish pharmaceutical company Astra AB . In 1957 the development of local anesthetics advanced with the synthesis of mepivacaine , in 1963 of bupivacaine , 1958 of prilocaine and 1976 of articaine. In 1981 intraligamentary anesthesia was developed as a new method of anesthesia. The first attempts were made in France as early as 1920, where the "Anesthésie par injections intraligamenteuses" is reported. At the time, it could not establish itself as the standard method due to the instruments available.

Reward

Germany

Like most medical treatments, local anesthesia is provided according to service contract law (not according to service contract law ). This means that proper treatment is owed and in this case can also be billed. However, the success of the treatment, i.e. the occurrence of sufficient anesthesia, is not owed. For local anesthesia, this means that - after it has been carried out properly - but with insufficient onset of action (see above: anesthesia failure) - it can be provided again and billed.

Statutory health insurance

In Germany, in accordance with the guidelines of the Federal Joint Committee for adequate, appropriate and economical contract dental care, pain is eliminated by infiltration anesthesia for treatment in the upper jaw, and by conduction anesthesia for major interventions or inflammatory processes and for surgical treatment in the lower jaw. In addition to performance anesthesia, infiltration anesthesia is usually not indicated. This does not apply to a pardontal treatment . In the case of surgical and periodontal surgical services, the infiltration anesthesia can be billed in addition to the conduction anesthesia in justified exceptional cases, if this is the only way to achieve a sufficient depth of anesthesia or to eliminate the anastomoses . In accordance with the assessment standard for dental services (BEMA), local anesthesia in Germany is covered by the statutory health insurance companies according to the

- BEMA no. 40 infiltration anesthesia with 8 points (approx. € 7.50). (The service can only be billed once per session in the area of two adjacent teeth (exception: the two central incisors or in the case of intraligamentary anesthesia, in which the infiltration anesthesia is billed per tooth),

- BEMA no. 41a intraoral central anesthesia with 12 points (approx. € 11.20),

- BEMA no. 41b extraoral conduction anesthesia with 16 points (approx. € 15),

honored (as of July 2014). The costs of the anesthetics used are covered by the fee. Intraoral surface anesthesia and pain elimination through TENS and CCLADS are not contractual services.

If the procedure takes a long time and the anesthesia is less effective, it can be performed again and billed.

Private treatment

According to the private fee schedule for dentists (GOZ), local anesthesia is calculated according to the following GOZ items:

- GOZ no. 0080 Intraoral surface anesthesia, 30 points per half of the jaw or anterior tooth area (when applying the 2.3-fold rate approx. € 3.88)

- GOZ no. 0090 Intraoral infiltration anesthesia, 60 points (when applying the 2.3-fold rate approx. 7.76 €)

- GOZ no. 0100 Intraoral anesthesia, 70 points (when applying the 2.3-fold rate approx. € 9.05)

- GOZ extraoral conduction anesthesia: analogue calculation in accordance with GOZ § 6 para. 1

If the service according to number 0090 is charged more than once per tooth, this must be justified in the invoice. For the services according to numbers 0090 and 0100, the costs of the anesthetics used are separately billable (approx. € 1 per cylinder ampoule). Eliminating pain through TENS or CCLADS are not included as a service in the BEMA or the GOZ. The calculation can be made as a demand benefit according to § 2 Paragraph 3 GOZ - for GKV patients by prior agreement in accordance with the federal contract - dentists § 4 par. 5 (BMV-Z) or substitute health insurance contract dentists § 7 par.

Austria

According to the Autonomous Fee Guidelines (AHR) of the Austrian Dental Association (which, however, are not binding), the fee for any type of local anesthesia in dentistry is € 20. This applies if a dentist of choice (dentist who has not signed a contract with a regional health insurance company and therefore does not accept a dental treatment certificate) is active.

Switzerland

Swiss dentists are not bound by any tariff. In accordance with the Swiss Dental Tariff , which is only binding for members of the Swiss Dental Association (SSO), the fee is determined by multiplying the tax point number for the treatment of private patients with the tax point value (TPW), which is a maximum of SFr for infiltration anesthesia. 5.80 (as of 2014), but can also be below. According to item 4065, a tax point number of 11 applies for infiltration anesthesia, which amounts to a maximum of SFr. 63.80 (converted € 58.82) results.

In the case of social security cases that fall under the Accident Insurance Act and the Health Insurance Act, both the tax point number and the tax point value (CHF 3.10) are fixed per service. This results in a fee of SFr for an infiltration anesthesia. 34.10 (converted 31.44 €).

See also

literature

- Walter Artelt : German dentistry and the beginnings of anesthesia and local anesthesia. In: Dental communications. Volume 54, 1964, pp. 566-569, 671-677, 758-762 and 853-856.

- HC Niesel, H. Wulf, HK Van Aken: Local anesthesia, regional anesthesia, regional pain therapy . 3. Edition. Georg Thieme, 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-154753-8 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- N. Schwenzer: Oral and maxillofacial medicine: Dental surgery . 3. Edition. Georg Thieme, 2000, ISBN 978-3-13-116963-1 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- HV Makowski, JF Reuther, P. Kuleszynski: Anesthesia in dentistry: local and general anesthesia in dentistry, oral medicine and maxillofacial medicine . Hüthig, 1978, ISBN 978-3-7785-0442-0 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- HA McLure, AP Rubin: Review of local anesthetic agents. In: Minerva Anestesiol. Volume 71, No. 3, 2005, pp. 59-74, PMID 15714182 , minervamedica.it (PDF; 113 kB).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ HA Adams, E. Kochs, C. Krier: Current anesthesia techniques – an attempt at classification. In: Anaesthesiology, intensive care medicine, emergency medicine, pain therapy: AINS. Volume 36, No. 5, 2001, pp. 262-267, ISSN 0939-2661 , doi: 10.1055 / s-2001-14470 , PMID 11413694 (review).

- ^ HC Niesel, HK Van Aken: Local anesthesia, regional anesthesia, regional pain therapy . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, 2003, ISBN 978-3-13-143412-8 , pp. 586 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ P. Jöhren, G. Sartory: fear of dental treatment - phobia of dental treatment: etiology, diagnosis, therapy . Schlütersche, 2002, ISBN 978-3-87706-613-3 , p. 51 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Gander T., Kruse AL, Lanzer M, Lübbes H.-T., local anesthetics - mechanism of action and risks (PDF) Swiss Dental Journal, SSO, 125: pp. 44–45 (2015). Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ↑ HC Niesel, H. Wulf, HK Van Aken: Local anesthesia, regional anesthesia, regional pain therapy . 3. Edition. Georg Thieme, 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-795403-3 , p. 556 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Roman Huber: Checklist for complementary medicine . Karl F. Haug, 2014, ISBN 978-3-8304-7369-5 , pp. 268 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Friedrich Paukisch: The History of the pressure anesthesia, old and new . Edelmann, 1936, p. 12 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Y. Nir, A. Paz, E. Sabo, I. Potasman: Fear of injections in young adults: prevalence and associations . In: American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Volume 68, Issue 3, 2003, pp. 341-344. PMID 12685642 . Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ Demetra D. Logothetis: Local Anesthesia for the Dental Hygienist . 1st edition. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2013, ISBN 978-0-323-29133-0 , pp. 100 f . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Carpule for receiving a drug , WO 2001030418 A2, Google Patent. Retrieved September 7, 2014

- ^ Klaus Rötzscher: Forensic dentistry . BoD - Books on Demand, 2003, ISBN 978-3-8334-0372-9 , p. 35.

- ^ A b K.B. Bassett, AC DiMarco, DK Naughton: Local anesthesia for dental professionals . Pearson, 2009, ISBN 978-0-13-158930-8 , pp. 286 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Karger, Infusion Therapy and Clinical Nutrition . Volume 3, pp. 181, 1976 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Norbert Schwenzer: Surgical basics. Georg Thieme Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-13-159084-8 , p. 266 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ Stanley F. Malamed: Handbook of Local Anesthesia . Elsevier Health Sciences, April 25, 2014, ISBN 978-0-323-24202-8 , p. 305.

- ↑ Norbert Schwenzer: Surgical basics. Georg Thieme Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-13-159084-8 , p. 291 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ Markus DW Lipp: Emergency training for dentists: prophylaxis, diagnosis, therapy . Schlütersche, 1997, ISBN 978-3-87706-465-8 , p. 92 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ HC Niesel, H. Wulf, HK Van Aken: Local anesthesia, regional anesthesia, regional pain therapy . 3. Edition. Georg Thieme, 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-795403-3 , p. 604 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b c d e Norbert Schwenzer: Tooth-oral-maxillofacial medicine: Dental surgery . Georg Thieme, 2000, ISBN 978-3-13-116963-1 , p. 20th ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ HC Niesel, HK Van Aken: Local anesthesia, regional anesthesia, regional pain therapy . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, 2003, ISBN 978-3-13-143412-8 , pp. 613 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ ADA Status report, Journal of the American Dental Association (JADA) 1983, Volume 106, pp. 222-224. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ Local anesthesia: pain, pressure, discomfort , ZMK, February 3, 2016. Accessed July 11, 2019.

- ↑ Eberhardt Krüger: Anesthesia - Local Anesthesia - Intraligamentary Anesthesia . Medeco, Dental Atlas. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ Walter admission: The intraligamentary anesthesia in the dental practice. ( Memento of December 14, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) In: Zahnärztliche Mitteilungen , ZM-online, Heft 6/2001, p. 46. Retrieved on September 1, 2014.

- ↑ E. Kaufman, P. Weinstein, P. Milgrom: Difficulties in achieving local anesthesia. In: Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). Volume 108, No. 2, 1984, pp. 205-208, ISSN 0002-8177 , PMID 6584494 .

- ^ Schwenzer N, Ehrenfeld M, Dental, Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine - Surgical Basics, Georg Thieme Verlag (2008), ISBN 978-3-13-593404-4 .

- ↑ M. Berakdar, A. Kasaj et al .: Comparative studies between conventional local anesthesia and a new injection method AMSA - The Wand in non-surgical periodontal therapy. (PDF) In: Die Quintessenz , Volume 77, Issue 5, 2004, pp. 783–787. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ S. Malamed, Anesthetic Agents and Computer Controlled Local Anesthetic Delivery (CCLAD) in Dentistry ( Memento of 30 June 2014 Internet Archive ), PennWell, Review. Retrieved September 1, 2014

- ↑ MN Hochman: A new technology for single-tooth anesthesia and further development of intraligamentary anesthesia. (PDF) In: Die Quintessenz , Volume 58, Issue 3, 2007, pp. 301–307. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ^ MA Baumann, R. Beer: Endodontology . Georg Thieme, 2007, ISBN 978-3-13-155002-6 , p. 62 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ ES Jungck and D. Jungck: 11 years of experience with TENStem . (PDF) Association of German Doctors for Algesiology - Professional Association of German Pain Therapists. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ Mark I. Johnson: Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS): Research to Support Clinical Practice . Oxford University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-967327-8 , pp. 23 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Elliot V. Hersh, Andres Pinto et al. a .: Double-masked, randomized, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of intranasal K305 (3% tetracaine plus 0.05% oxymetazoline) in anesthetizing maxillary teeth. In: The Journal of the American Dental Association. 147, 2016, p. 278, doi: 10.1016 / j.adaj.2015.12.008 .

- ^ D. Jankovic: Regional blockades & infiltration therapy: textbook and atlas . ABW Wissenschaftsverlag, 2008, ISBN 3-936072-76-0 , p. 25 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ D. Jankovic: Regional blockades & infiltration therapy: textbook and atlas . ABW Wissenschaftsverlag, 2008, ISBN 3-936072-76-0 , p. 8 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Saklad M. Grading of Patients for Surgical Procedures. Anesthesiology 1941; 2: 281-4.

- ^ PH Mak, RC Campbell, MG Irwin: The ASA Physical Status Classification: inter-observer consistency. American Society of Anesthesiologists. In: Anesthesia and intensive care. Volume 30, Number 5, October 2002, pp. 633-640, PMID 12413266 .

- ^ Astrid Kruse Guter, Christine Jacobsen, Klaus W. Grätz: Specialist knowledge of oral and maxillofacial surgery . Springer, 2013, ISBN 978-3-642-30003-5 , pp. 51 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Monika Daubländer, Peer Kämmerer: Local anesthesia in old age. In: Dental communications . Issue 10/2012, pp. 38–45. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ H. Müllmann, K. Mohr, L. Hein: Pharmacology and Toxicology: Understanding drug effects - using drugs in a targeted manner . Georg Thieme, 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-368517-7 , p. 101 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Norbert Schwenzer: Tooth-mouth-jaw medicine: Dental surgery . Georg Thieme, 2000, ISBN 978-3-13-116963-1 , p. 6 . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Ultracaine Information. (PDF; 68 kB) As of 2010, pharmazie.com; accessed on September 1, 2014.

- ↑ Ultracain specialist information. (PDF) Sanofi Aventis. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ Judith Pfeiffer, Comparative experimental study on the influence of different concentrations of the vasoconstrictor adrenaline on the depth and duration of anesthesia of Articain in 4% solution, dissertation, Universitätsmedizin Mainz, 2001.

- ↑ Stanley F. Malamed: Handbook of Local Anesthesia . Elsevier Health Sciences, April 25, 2014, ISBN 978-0-323-24202-8 , p. 285.

- ↑ EV Hersh, PA Moore, AS Papas, JM Goodson, LA Navalta, S. Rogy, B. Rutherford, JA Yagiela: Reversal of soft-tissue local anesthesia with phentolamine mesylate in adolescents and adults. In: Journal of the American Dental Association . Volume 139, No. 8, 2008, pp. 1080-1093, ISSN 0002-8177 . PMID 18682623 .

- ↑ M. Daubländer, D. Kauschat-Brüning: OraVerse® - the current status. In: ZMK , Volume 29, Issue 9, 2013, status November 5, 2013. Accessed on August 31, 2014.

- ↑ KZBV yearbook. Basic statistical data on contract dental care / 2013. National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Dentists (KZBV), 2013, ISBN 978-3-944629-01-8 .

- ↑ Derived from: T. Keßler: Service expenditure and frequency distribution of fee rates in outpatient medical care 2005/2006. ( Memento of July 28, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) WIP discussion paper 2/08, Scientific Institute of the PKV, 2008. Accessed on August 31, 2014.

- ↑ HC Niesel, H. Wulf, HK Van Aken: Local anesthesia, regional anesthesia, regional pain therapy . 3. Edition. Georg Thieme, 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-795403-3 , p. 617 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Martin S. Spiller, Gow-Gates-Technik ( Memento of the original from July 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (English). Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- ↑ HC Niesel, H. Wulf, HK Van Aken: Local anesthesia, regional anesthesia, regional pain therapy . 3. Edition. Georg Thieme, 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-795403-3 , p. 618 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ HC Niesel, H. Wulf, HK Van Aken: Local anesthesia, regional anesthesia, regional pain therapy . 3. Edition. Georg Thieme, 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-795403-3 , p. 620 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Hugo Van Aken: Local anesthesia, regional anesthesia, regional pain therapy . Georg Thieme Verlag, 2003, ISBN 978-3-13-143412-8 , p. 537.

- ↑ AP Saadoun, p Malamed: intraseptal anesthesia in periodontal surgery. In: Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). Volume 111, No. 2, August 1985, pp. 249-256, ISSN 0002-8177 . PMID 3876361 .

- ↑ HC Niesel, H. Wulf, HK Van Aken: Local anesthesia, regional anesthesia, regional pain therapy . 3. Edition. Georg Thieme, 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-795403-3 , p. 602 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Thomas Weber: Memorix dentistry . Georg Thieme, 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-114373-0 , p. 279 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ JC Türp: Therapeutic local anesthesia for the treatment of atypical odontalgia. (PDF) In: Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. Volume 115, 2005, pp. 1012-1018. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ M. Ratschow: Critical to the range of effects of neural therapy (therapeutic anesthesia). In: Acta Neurovegetativa. 3, 1951, pp. 198-210, doi: 10.1007 / BF01229036 .

- ^ W. Dörr, J. Haagen et al .: Treatment of oral mucositis in oncology. ( Memento from November 23, 2015 in the web archive archive.today ) In: In Focus Oncology. No. 7-8, 2010, pp. 1-5. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ Christoph Klaus Müller, The local anesthesia. What are the risks from a general medical perspective? , Zahnärzteblatt Baden-Württemberg, 03/2011 edition. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ↑ Cocaine effects. Drug net; accessed on October 21, 2016.

- ↑ W. Zink, BM Graf: Toxicology of local anesthetics. Pathomechanisms - Clinic - Therapy. In: Anaesthesiologist. Volume 52, No. 12, 2003, pp. 1102-1123, PMID 14691623 , uni-heidelberg.de (PDF; 462 kB).

- ↑ RSR Buch et al .: Dolor post extractionem - The local therapy of alveolitis with medicinal insoles. In: zm 95, no. 20, October 16, 2005, pp. 54–58.

- ↑ Kirsten Schmied, Der Zappelphilipp bei Zahnarzt , October 2, 2015. Accessed July 11, 2019.

- ↑ Berthold Langguth et al., Unwanted Wakefulness during Anesthesia , Deutsches Ärzteblatt, vol. 108, issue 31–32, p. 541, August 8, 2011. Accessed July 11, 2019.

- ^ Rainer Laufkötter, Berthold Langguth, Monika Johann, Peter Eichhammer, Göran Hajak: ADHD in adulthood and comorbidities. In: psychoneuro. 31, 2005, p. 563, doi : 10.1055 / s-2005-923370 , PDF .

- ↑ Differential therapy after damage to the lingual and inferior alveolar nerves. ( Memento of February 2, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF)

- ^ Scientific opinion of the German Society for Dentistry, Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine (DGZMK). Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ↑ Thomas Weber: Memorix dentistry . Georg Thieme, 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-114373-0 , p. 14th ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ F. Hofmann, N. Kralj, M. Beie: Needle stick injuries in health care - frequency, causes and preventive strategies. In: Health Service (Federal Association of Doctors of the Public Health Service (Germany)). Volume 64, No. 5, 2002, pp. 259-266, ISSN 0941-3790 , doi: 10.1055 / s-2002-28353 , PMID 12007067 ( full text ).

- ↑ M. vd Heuvel: Appropriate waste disposal in the dental practice. (PDF) In: Bayerisches Zahnärzteblatt. 11/2012, pp. 38-40. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ a b Protection against needlestick injuries in health care and nursing (PDF) Small Inquiry, Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 18/9654 18th electoral term September 19, 2016. Accessed October 24, 2016.

- ↑ Pierre Van Damme, Koen Van Herck: A review of the long-term protection after hepatitis A and B vaccination. In: Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 5, 2007, p. 79, doi: 10.1016 / j.tmaid.2006.04.004 . PMID 17298912 .

- ↑ Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunization: Chapter 18 Hepatitis B . In: Immunization Against Infectious Disease 2006 ("The Green Book") (), 3rd edition (Chapter 18 revised October 10, 2007). Edition, Stationery Office, Edinburgh 2006, ISBN 0-11-322528-8 , p. 468. Archived from the original on January 7, 2013.

- ↑ WHO Model List of Essential Medicines . In: World Health Organization . October 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ↑ Jiri Beran: Bivalent inactivated hepatitis A and recombinant hepatitis B vaccine. In: Expert Review of Vaccines. 6, 2007, p. 891, doi: 10.1586 / 14760584.6.6.891 .

- ↑ Biological Agents Ordinance of July 15, 2013 (BGBl. I p. 2514). (PDF) Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection . Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ TRBA 250 Biological agents in health and welfare work. (PDF) Status: May 2, 2018, Committee for Biological Agents (ABAS), Item 4.2.5, Item 5. Accessed on August 21, 2019.

- ^ Regulations of the TRBA 250. ( Memento from July 15, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) SAFETY FIRST! Germany, ipse Communication. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ↑ Needle Prick Ordinance. Version dated May 11, 2013, Legal Information System of the Republic of Austria (RIS). Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ↑ Lothar Taubenheim, The intraligamentary anesthesia: reducing reservations , Dental Implantologie, November 15, 2013. Accessed February 1, 2016.

- ↑ R. Rahn: Fitness to drive after local dental anesthesia and dental interventions. ( Memento from August 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) ZBay Online, 12/1999. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ↑ Obligation to inform about treatment alternatives to infiltration or conduction anesthesia, intraligamentary anesthesia , Higher Regional Court Hamm, judgment of April 19, 2016, Az. 26 U 199/15

- ↑ G. Kluxen: Sigmund Freud: About Coca - Missed discovery. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. Volume 88, No. 45, 1991, pp. A-3870.

- ↑ Harry Safe: Anatomy and technology of central anesthesia in the area of the oral cavity: A textbook for the general dentist . Springer-Verlag, March 7, 2013, ISBN 978-3-642-92263-3 .

- ↑ by Sinatra / year / Watkins-Pitc: The Essence of Analgesia and Analgesics - Sinatra / year / Watkins-Pitc . ISBN 1-139-49198-9 , pp. 280 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ HC Niesel, H. Wulf, HK Van Aken: Local anesthesia, regional anesthesia, regional pain therapy . 3. Edition. Georg Thieme, 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-795403-3 , p. 79 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ A. Langbein: Local anesthesia that is gentle on the patient during dental therapeutic measures with a special focus on intraligamentary anesthesia as the primary method of eliminating pain. (PDF) Dissertation, Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich 2011. Retrieved on September 1, 2014.

- ↑ Guideline of the Federal Joint Committee for an adequate, appropriate and economical dental care contract. (PDF) IV No. 6, Federal Committee of Dentists and Health Insurance Funds , March 1, 2006. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- ↑ a b Dental fee lists. National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Dentists (KZBV). Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ↑ Schedule of Fees for Dentists (GOZ). (PDF) German Dental Association , as of December 5, 2011. Accessed on September 3, 2014.

- ^ Federal cover contract for dentists BMV-Z and replacement insurance contract for dentists EKV-Z. National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Dentists , as of April 1, 2014. Accessed on September 3, 2014.

- ↑ Autonomous Fee Guidelines 2014/2015. ( Memento from January 20, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Austrian Dental Association, June 13, 2014. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- ↑ Dental tariff, short version. (PDF) Swiss Dental Association (SSO). Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ↑ Dentist tariff. (PDF) Swiss Dental Association (SSO). Retrieved August 31, 2014.