History of dentistry

The history of dentistry or the history of dentistry encompasses the developments in dentistry including the contributions of people who influenced dentistry of their time. It is part of medical history and goes back to prehistory . The conservative treatment of teeth was established in a 14,000 year old male from the rock cave of Riparo Villabruna near Sovramonte in northern Italy, and also for the period around 5500 to 7000 BC. With farmers in Pakistan . Carious teeth were precisely drilled open , possibly combined with a subsequent filling of the cavity. Also from the Neolithic Age comes a molar tooth from Denmark that was trepanated . The first dental work was done in the middle of the 1st millennium BC. Made by Etruscans and Phoenicians . The influence of Roman and Greek scholars was decisive in the Middle Ages in both Christian and Arab countries. The Arabic knowledge, along with many ancient ones, came through the translation school in Toledo and via Salerno to the occidental region, where dentistry was practiced by the barbers .

From the Sumerians to modern times, the belief that a toothworm is the cause of tooth decay has persisted. Science laid the foundation for modern dentistry at the beginning of the 18th century, primarily through the French Pierre Fauchard . From the 19th century, dental treatment under anesthesia was carried out with nitrous oxide , which was synthesized as early as 1776. Ether and chloroform anesthesia followed the nitrous oxide. The US dentist William Thomas Green Morton was able to relieve a patient of their suffering for the first time without pain.

In November 1895, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen discovered the X-rays , later named after him , which simplified the examination of the jaw. The local anesthetic procaine was developed in 1905 by the German chemists Alfred Einhorn and Emil Uhlfelder , who assigned the active ingredient the name novocaine (Latin word for "new cocaine") as a local anesthetic for toothache . This laid the foundations for modern diagnostics and therapy. Dentistry then experienced rapid progress: from the development of numerous oral surgical procedures to the manufacture of dentures using CAD / CAM processes. In parallel with the progress of scientific dentistry, the job description developed, which is represented in the history of the dental profession . In addition, animal dentistry developed, which uses modified methods of general dentistry.

The Danish Hedvig Lidforss Strömgren (1877–1967) and the German Walter Hoffmann-Axthelm are among the most important researchers on the history of dentistry .

Preliminary remark

The history of medicine (including that of dentistry, also called dentistry and outdated dental art ) is researched using historical and sometimes ethnological methods. The main sources used are medical texts, medical records, historiography or diaries, letters, literary texts and ethnographic records and interviews. The examination of human remains and ancient pathogens does not fall into the methodology of medical history, but rather paleopathology , but is considered for the sake of completeness.

prehistory

For a long time it was believed that because of diet, hunters and gatherers were not affected by tooth decay . From the Middle Paleolithic of Europe and Western Asia, i.e. the time of the Neanderthals , hardly any cases of tooth decay are known, if so as a result of a diet-related enamel fracture . In September 2013, however, the results of investigations on 52 skeletons in the Grotto des Pigeons in eastern Morocco from 15,000 to 13,700 years ago were published, which shows that these hunters and gatherers were already suffering from tooth decay. This is in contrast to the previous assumption that this dental disease only arose through the consumption of carbohydrates from grain production , i.e. only in the Neolithic Age. Apparently this goes back to acorns of the holm oak , pine nuts of the maritime pine and pistachios of the turpentine pistachio . In view of the widespread, probably ritual removal of the anterior teeth , it is all the more surprising that there was no evidence of the removal of carious teeth, even if painful abscesses had developed.

In 2015, a carious molar tooth of a 14,000-year-old male was examined, the remains of which were found in 1988 in the rock cave of Riparo Villabruna near Sovramonte in northern Italy. The results show that the hole in the tooth was machined with a very small, pointed stone blade to remove infected tissue. Until then, dental treatments were known about 7,500 to 9,000 years ago in today's Pakistan , as evidenced by finds in Mehrgarh ( Balochistan ), one of the most important archaeological sites for a prehistoric settlement group in South Asia . The residents appear to have been skilled jewelry makers and also used their skills to drill small carious cavities with stone tools such as those used to make pearl necklaces. The reconstruction of the origins of dentistry shows that the methods of treatment of the time were apparently very effective. The earliest tooth filling made from beeswax was discovered in Slovenia and is around 6,500 years old. A fractured canine was restored with it.

Very early evidence is also available for trephination : During excavations in Denmark, an approximately 5000 year old trepanned molar (molar) was found.

Finds from Italy and Tunisia prove tooth removal in the early Mediterranean region. Apparently, teeth were removed frequently, at least in every third adult woman. However, since there are no other traces of violence in the facial area, this was probably due to cosmetic, ritual or social reasons, such as status reasons. The distance may have been related to growing up. The presumption of a ritual function is suggested by ethnological comparisons. Ritual tooth extraction was common among many Australian Aboriginal tribes . The Himba people living in Namibia and the Surma people from Ethiopia had the custom of breaking out the lower four incisors of children between the ages of seven and nine. Originally, this “gap” was supposed to serve as a counter bearing for a lip plug or a disc. Both African tribes have a cultural element in common, which can be explained by their common descent from the Herero , an East African, semi-nomadic people.

The development of ideas about the development of tooth decay

Medicinal belief in the toothworm

A Sumerian text from around 5000 BC. BC, so claimed Suddick and Harris 1990, describes the toothworm as the cause of tooth decay for the first time . The authors misinterpret a publication by Hermann Prinz from 1945. If one follows Astrid Hubmann's dissertation, it becomes apparent that four sources, the oldest from around 1800 BC. BC dates to prove the belief in the toothworm. It is a sheet of Nippur .

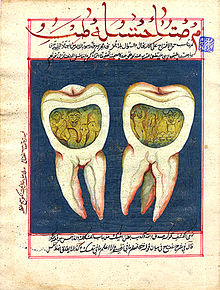

A plaque discovered at Assur suggests that toothworm and toothache were treated differently, which could suggest an understanding of them as different diseases. From the library of the Assyrian king Assurbanipal (669–631 / 627 BC) comes the work of a Nabunadinirbu, which is entitled When a person has a toothache . Possibly it is a copy of a considerably older Babylonian text in which, in addition to the description of a treatment, a ritual incantation is of particular importance. In this, the worm, probably a demon or evil spirit, rejects the gifts of the highest god Anu , namely ripe figs , apricot and apple juice, and prefers the blood of the teeth.

In the scriptures it says: “When Anu created heaven, heaven created earth,… the swamp created the worm, then the worm went crying to Shamash (the sun god)… Lift me up and let me dwell between teeth and gums! I want to drink the blood of the teeth, I want to eat the roots of the gums! ”Then follows an incantation which is supposed to banish the“ demon toothworm ”:“ Because you said this, worm, may the god Ea strike you with his strong hand! “This text has to be spoken three times. Then a pain-relieving mixture of different herbs is placed on or in the tooth. The personal physician of the Roman emperor Claudius , Scribonius Largus, recommended in the 1st century AD to kill the toothworm by smoking it with the narcotic black henbane ( Hyoscyamus niger ). He describes his experiences here: "Sometimes something that looks like small worms is brought out."

Other recommendations were to mix emmer mixed beer, broken malt and sesame oil and apply to the affected tooth. Basically, it was believed that worms could emerge from rotten juices anywhere in the body. Since ancient times it has been believed that an imbalance of the four body fluids - blood (sanguis), mucus (phlegma), yellow bile (cholera or chole, Greek: χολή), black bile (melancholia, from Greek melanos and chole: μέλανος , χολή) - would cause diseases. In order to cure a patient, one had to remove excess or spoiled juices. This happened, for example, by bloodletting , sweating, urine and stool regulating agents. The doctrine of the juices represented a substantial advance over earlier views, which had seen man's condition as determined by the gods alone. With the humoral pathology , the ancient doctors began to systematically describe the specific tendencies towards illness.

Also in ancient India (around 650), in Egypt - here it is the papyrus Anastasi IV , 13, 7 (around 1400 or around 1200/1100 BC) - as in Japan and China , a sick tooth was a "worm tooth" , but also among the Aztecs - there, for example, tobacco was put into the cavity - and the Maya , indications were found that the toothworm was the cause of tooth decay. The legend of the toothworm can also be found in the writings of Homer, and in the 14th century the surgeon Guy de Chauliac believed that worms caused tooth decay.

The Compositiones medicamentorum by Scribonius Largus , the personal physician of Emperor Claudius , had a strong influence in the Old World . For the treatment he recommended Zahnräucherungen and conditioners, as well as deposits and chew and fumigation with henbane seeds , which for this reason as herba dentaria were called. He indicates that some worms are sometimes spit out during treatment. So people continued to believe in the worm, but also tried to accelerate the falling out of diseased teeth by laying on worms. Pliny the Elder, however, did not believe in the existence of the toothworm, but in a similar healing effect. Pliny also mentions the ingredients of the tooth cleaning powder he recommends called "Dentifricium" (ὀδοντότριμμα): powdered or burned bones , horn or mussel shells , pumice powder , soda , mixed with myrrh . Celsus, on the other hand, recommended ground salt. Tooth salt is still used today, especially in Asia.

In the Arabic-speaking world, toothworms were believed to be based on older traditions. This is shown by the work of Muhammad ibn Zakarīyā ar-Rāzī , who saw the relationship between body and soul as determined by the soul, as well as the works of Avicenna or Abulcasis . ʽ Umar ad-Dimašqi , who taught in Damascus around 1200 , rejected the toothworm, especially the charlatanry carried on with worms , in his book The Chosen One about revealing secrets and tearing the veil .

Around this time, Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179) also believed in worms, but recognized poor hygiene as the cause. The purpose of rinsing with water was to avoid the livor , a deposit that could settle around the tooth and produce the dreaded worms. She recommended aloe and myrrh and coal smoke. Constantinus Africanus , who came to Salerno from Tunisia , made the medical university there famous in the early 11th century. He brought ancient knowledge and also the theory of humours to the north, but also confirmed the tooth worm, which had also found its way into conventional medical works. For example, in the tract Practica brevis by Johannes Platearius from Salerno, written in the 12th century, which describes the (humoral pathological) causes and therapeutic options for toothache, but also the toothworm, the development of which he attributes to the putrefaction of juices in holes in molars and its treatment he recommends centaury juice, myrrh and opium as a topping or as an awl, and henbane smoke. Medieval dentistry reports on the use of frog fat to allegedly facilitate tooth removal by Petrus Hispanus and John of Gaddesden (1280–1348 / 49 or 1361), writings on rubbing in with milkweed for toothache or the recommendation of earthworm oil by Arnaldus de Villanova (~ 1235-1311). The famous West Flemish surgeon Jan Yperman (1269/65 to around 1350) also explained the pus formation that occasionally occurs in diseased teeth with the movement of worms. Sometimes charlatans took over the worm theory. For example, they hid earthworms in food that the pain-afflicted person was supposed to suck to "numb" them. They then removed the worm that had emerged from their mouths to the applause of the amazed crowd.

Scientific theories

It was not until the 19th century that various theories about the development of tooth decay were developed that replaced the ideas based on humoral pathology . In 1843 the worm theory was developed into a parasite theory by the Munich anatomist Michael Pius Erdl (1815–1848) . It was followed by the inflammation theory according to Leonhard Koecker or special metabolic products of the chemical conversion of food components were made responsible for the development of caries. In 1825, London dentist Andrew Clark saw dental disease as a result of the diet of wealthy people and concluded that simpler people who were used to a hard life usually had healthy, caries-free teeth.

The American Willoughby D. Miller (1890), who during his thirty years of activity in Germany also received bacteriological training from Robert Koch (1843–1910) at Berlin University , developed the "chemoparasitic theory", according to which lactic acid bacteria continued into the 1960s Years were seen as the cause. Miller was president of the Central Association of German Dentists (CVdZ) for six years . At the 4th International Meeting of Dentists in St. Louis in 1904, he was elected President of the Fédération Dentaire Internationale . The Miller needle he developed , a probe used in dentistry to find and probe root canals, is named after him. His saying went down in history: “ A clean tooth never decays. ”(Loosely translated:“ A clean tooth doesn't get sick. ”) Paul Keyes finally discovered in 1960 that Streptococcus mutans is the cause of caries.

The most diverse theories followed one after the other:

- the "tooth lymph theory" (Charles F. Bodecker, 1929)

- the " proteolysis theory" ( Bernhard Gottlieb , 1944)

- the "ulciphilia theory" (Sten Forshufvud, 1950)

- the "organotropic caries theory" (Charles Leimgruber, 1951)

- the "resistance theory" (Adolph Knappwost, 1952)

- the "Corrosion Theory" (Ulrich Rheinwald, 1956)

- the "pulp phosphatase theory" (Julius Csernyei, 1956)

- the "glycogen theory" (Peter Egyedi, 1956)

- the "non-acidic caries theory" (Halfdan Eggers-Lura, 1962)

- the "proteolysis- chelation theory" (Albert Schatz and Joseph J. Martin, 1962)

- the "unspecific plaque hypothesis" (Walter Joseph Loesche, 1976), with which the development of periodontitis was also discussed

- the "specific plaque hypothesis", (RC Page, HE Schroeder, 1976)

Ecological plaque hypothesis

Only subsequently was made a paradigm shift by Philip D. Marsh (1994), which led to the "ecological plaque hypothesis." Due to several pathogenic factors, the hard tooth tissue is destroyed in several stages: A continuous availability of fermentable carbohydrates , which leads to a permanently lowered pH value , is the driving force behind the destruction of a bacterial homeostasis of plaque (dental plaque). The acidic environment stimulates the reproduction of acid-producing and acid-tolerant germs such as mutans streptococci and lactobacilli . There is also an interaction between Streptococcus mutans and the fungus Candida albicans , which causes the bacterium to change its virulence . The fungus produces signaling molecules that stimulate the bacterium's genes to produce antibiotics in the cell . The bacterium can absorb foreign genetic material through the fungus.

By the end of the 20th century, however, the belief in the toothworm as the cause of pain was preserved in rural areas of China and was exploited by many quacks . Three of these scams from 1985, 1987 and 1993 are also reported in Taiwan.

If the macroscopic "toothworm" is ridiculed in modern times, the bacteria and fungi undoubtedly appear worm-like in modern microscopes .

Early dentistry

Orient

Predynastics :

3 periapical granuloma

Macedonian period :

2 abrasion teeth

Roman period :

5 osteolysis

Coptic period :

1 palatal perforation, 4 cyst

The first dentist known by name in world history (and at the same time a doctor) is said to have been Hesire in ancient Egypt (around 2700 BC), who was honored with the title wr-ibḥ-swnw as "the great of dentists and doctors". A basalt statue of Psammetich-Seneb (around 600 BC) in the Vatican Museum shows that he was called the "chief physician of the dentists at court". However, his title as a doctor is just one of his many titles and may have been symbolic rather than practical. The translation of the title is also not certain, alternatives such as “the great ivory and arrow carver” have been suggested.

The Ebers papyrus , a medical papyrus from ancient Egypt, describes around 1600 BC. In addition to the Edwin Smith papyrus (1550 BC), which is one of the oldest surviving texts on medical topics, measures for the treatment of various dental diseases, in particular caries and periodontitis . It is believed that the Smith Papyrus is just a copy of a script that is at least 1,000 years older. The Smith Papyrus describes the treatment of mandibular fractures by means of manual reduction and a subsequent splint. With numerous archaeological finds, one can assume that some of the measures to be assessed as “therapy” took place post mortem as part of the mummification , as Egyptians placed great value on moving into the Osiris realm as intact as possible .

The grain was ground with stone mills . The bread was stained with stone grains. The teeth were chewed off by this and by the rough food. The tooth was partially ground down to the pulp . Cariogenic bacteria did the rest and the tooth became infected. Tooth extractions (tooth removals) were the exception. Stone flour , resins , malachite and plant seeds were used as tooth filling .

Dentistry is not mentioned in the Torah , but parts of the mouth are also mentioned in the context of the explanations in the 3rd book of Moses on anatomy . In a remarkable passage, the salivary glands are compared with water sources and the salivary duct is described as “duct (Ammat ha-mayim) that runs under the tongue” (Lev R. 16: 4.). This is interesting insofar as the salivary ducts of the salivary glands were not exactly described in the scientific literature until the 16th and 17th centuries (Lehi; Ar 15b). The position of the tongue (lashon) is described, which would lie between two “walls” made up of the jawbone (leset) and the cheek flesh.

Toothbrushes

In ancient times, dental hygiene began using twigs that were chewed with fibers, such as the miswāk , which was used as a toothbrush . The branch from the toothbrush tree ( Salvador persica ) contains cleaning agents, disinfectants and even fluoride . It was found in the ancient Indian collection of medical knowledge of the surgeon Sushruta (सुश्रुत, Suśruta) around 500 BC. Recommended. In addition, Sushruta is considered a pioneer of anesthesia , which he carried out with cannabis indica , among other things . Miswāk is also mentioned in the ancient Indian code of Manu ( Sanskrit , f., मनुस्मृति, manusmṛti ) at the turn of the ages. In the Islamic world, Mohammed is said to have used it regularly, according to the hadith literature . Also from other wood brushing rods were made, so in the Western Sahara , the Maerua crassifolia (from the family of capparaceae ). In Mauritania he is called (in the Arabic dialect Hassania ) as atīle . The toothbrush tree is called tiǧṭaīye there , and in this region the Commiphora africana from the balsam tree family , adreṣaīe and desert date ( Balanites aegyptiaca , in Hassania: tišṭāye ) are used to clean teeth. In southern Burkina Faso , teeth are cleaned with Zanthoxylum zanthoxyloides . In India, branches of the neem tree are used to brush teeth. In addition to toothbrushes, toothpicks have also been used since ancient times .

Greeks and Romans

Greek scholars such as Hippocrates (around 460-370 BC) and Apollonios von Kition (In: Περὶ ἄρθρων ( Perì árthrōn )) described the dentition (tooth eruption ). Hippocrates suggested head and chin bandages made of leather for jaw fractures and the fixation of the teeth adjacent to the fracture gap with gold wire. At the end of the 5th century, the Corpus Hippocraticum also mentions the removal of loose teeth for dental pain therapy.

Around 450 BC A commission in Rome was commissioned to draw up a constitution known as the Twelve Tables Act . There it says in Plate X , “One should not add gold to 'the corpse'. But anyone who has dentures on the basis of gold wire bandages, with which missing teeth are attached to the neighboring teeth by human or animal teeth with gold wire or gold bands, should not be an offense to bury or burn them, ”from which it can be deduced that back then Dentures were already widespread.

In Martial's epigrams (40–102 / 104), dentures are also mentioned: Sic dentata sibi videtur Aegle emptis ossibus indicoque cornu (“This is how Aegle sees himself toothed, thanks to purchased bones made from Indian horn.”) In the Roman Empire they were used So already the ivory ("Indian horn") for the production of artificial teeth.

Dental practitioners in ancient Rome were mostly Greek slaves who, with successful treatment, that is, pain-relieving treatment, were able to achieve their freedom and even rise up socially. Investigations of the remains of Romans demonstrated attempts in dental prosthetics and oral surgery . The importance of the teeth with the Romans around the turn of the times is shown by votive offerings , which consisted of clay-made dentures, but also by the dental care habits of the Romans, which are strange from today's perspective, who brushed their teeth with their urine.

Aulus Cornelius Celsus , a Roman medical writer, extensively described oral diseases as well as dental treatments including narcotics and astringents . The description of the four signs of inflammation ( rubor, tumor, calor, dolor , Latin: redness, swelling, warming, pain) also goes back to Celsus . In his Latin treatise De Medicina , he summarized the medical knowledge of the Alexandrian school in eight books. A section in the sixth book is devoted to the teeth, and the eighth book also provides initial information on orthodontic treatment .

Pliny the Elder compiled the natural history knowledge in his 37-volume work Naturalis historia and presented it to Emperor Titus in AD 77. In this work he devotes himself to dentistry in 169 scattered places. He also describes the dentition including its deviations, but these are not examined for their cause, but interpreted. Infants born with broken teeth were of particular importance. The spectators of the Valeria Messalina prophesied that she would lead her state to ruin. (The prophecy is said to have been fulfilled in Suessa Pometia ). Agrippina the elder is fortunate because she has two canine teeth ( dog teeth ) at the top right . More than 32 teeth would mean a long life. Pliny describes several dozen tinctures and remedies from the plant, animal and stone kingdoms. The naming of the tooth grates (odontītis) as a remedy for toothache is said to go back to him. He describes a teething aid , a mixture of honey and the ashes of dolphin teeth, various other tinctures or, for example, the teething aid consisting of a wolf's tooth or horse's tooth, which should alleviate teething problems in children through its magic. The history of the pacifier began with the development of artificial baby feeding , like a relief from around 900 BC. Shows from the palace of King Sardanapal of Nineveh . In Europe, pacifiers have been known at least since the Middle Ages, as can be seen from the illustrations. Unhygienic sucking bags were used as fabric pacifiers from the late Middle Ages to the 18th century. They were only replaced by rubber pacifiers in the second half of the 19th century.

From the time of Pliny there is also a description of the treatment of carious teeth and gum disease and how tooth extractions are to be carried out. Aristotle also describes extraction forceps for this purpose . There are also explanations on how to fix loosened teeth with tweezers and thin wires and how to splint jaw fractures .

Archigenes , (Ἀρχιγένης), a Greek military doctor under Trajan , came from Apamea , ( Syria ) and was a representative of a medical school known as the eclectic school. He was the son of Philippos (Φίλιππος) and pupil of Agathinos (Ἀγαθῖνος), the founder of the eclectic school, and developed the drill around 100 AD . After this used as a trephine for boring the skull, he came up with the idea to also have a sore tooth trepan to relieve the inflamed pulp. However, he never got the idea of drilling out carious dentin .

The physician Emperor Marcus Aurelius , Galen of Pergamon (ca. 130-210), attacked the orthodontic idea of Celsus and describes how teeth narrowed by filing and shaping, to reduce crowding. Galenos expanded the four signs of inflammation to include the feature of the functio laesa , the "disturbed function". In his work De ossibus ad tirones , he wrote that the lower jaw consists of two bones, which can be seen from the fact that it falls apart in the middle when cooking. The Arab doctor Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi had the opportunity to examine the remains of people who had starved to death during a famine in Cairo 1,000 years later. In his book Al-Ifada w-al-Itibar fi al-Umar al Mushahadah w-al-Hawadith al-Muayanah bi Ard Misr (Book of Instruction and Admonition on Seen Things and Recorded Events in the Land of Egypt) he contradicts Galenus that he did can only see the lower jaw as a single, seamless bone. Celsus and Galenus were the authoritative medical writers of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. Their influence was still decisive in the Middle Ages in both Christian and Arab countries.

Protection and relief through invocation of the saints

Dentistry initially became part of folk medicine and magic again . Toothache was one of the numerous ailments for whose relief and protection individual saints were invoked, who were believed to have a corresponding influence. In many cases, saints were chosen who, according to tradition, had suffered as martyrs from the same parts of the body.

Holy Apollonia

According to tradition, Apollonia of Alexandria , who died a martyr under Emperor Philip Arabs (244-249) , had her teeth torn out with pliers before she threw herself into the stake . Her feast day in the Catholic and Orthodox Churches is February 9th. Pope John XXI. (1276–1277) advised believers to say a prayer to Apollonia if they had a toothache. So she became a protector against toothache, but also the patron saint of dentists and all other professions in the dental field. Apollonia was canonized in 1634 by Pope Urban VII.

Grains of the common peony lined up on chains were called Apollonia grains in southern Germany and given to teething toddlers to chew. In France they were known as Herbe de St. Antoine . Other pain-relieving plants were also given corresponding names, such as the Apollonia root in Salzburgerland as the name for the wolf monkshood , a name that was also found in Bavaria, or the Apollonia herb ( henbane ).

Toothache god

The so-called "Toothache Lord God" from St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna is one of the few stone depictions of the Man of Sorrows still preserved in Austria . It was made around 1420 by an unknown artist and shows the half-length figure of Christ clad in an apron with a crown of thorns and wounds. As was customary in cultic veneration at that time, the figure was adorned with flowers that were attached to the head with a cloth. According to legend, three drunken boys saw Christ wearing this cloth and blasphemed that Jesus had a toothache . That same night the three boys themselves got in great pain. It was only when they returned to the cathedral the next day to apologize that their pain disappeared again. Since that time, the "toothache god" has been sought out by numerous Viennese to ask for relief from toothache.

Priests and barbers

In the Middle Ages, after the Migration Period , the level of healers in antiquity had not yet been reached, as demonstrated by a small prosthesis to replace one's own, previously fallen out central incisors , which was found in the Slavic burial ground of Sanzkow (Demmin district).

At the beginning of the Middle Ages, monks and priests performed medical and dental activities. Bader assisted them. The Second Lateran Council in 1139 threatened priests with severe sanctions if they engaged in treating. Pope Alexander III made a far-reaching decision at the Council of Tours in 1163 that bloody interventions were incompatible with the priestly office: Ecclesia abhorret a sanguine ("The Church shrinks from blood"). The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 finally forbade the medical profession in priestly garb from the practice of surgical measures, because guilt for the death of a person made the priesthood unfit. The medical science of the European Middle Ages then took a development that was only reversed in the 19th century.

The bather (lat. Balnĕator) was the owner or head of a bathing room, also known as the bathhouse . He was authorized to practice minor surgery and to shave. Since not every trained bather could afford a bathing room for financial reasons, a new profession of barbers emerged over time , who basically offered the same range of treatments, but without a bath. The barbers (from French barbe , "beard") were artisans according to their status and profession . Barbers are mentioned for the first time in an official letter from Cologne in 1397. But a relief on St. Mark's Basilica in Venice, which was made as early as the 13th century, shows a tooth extraction performed by a barber. Anything significant about dentistry could only be found in the Latin word for surgeons. the bathers couldn't read that. Superstition, alchemy and astrology therefore dominated the minds of most of the dentatores of the time, who were often not tied to a particular location .

In 1450, according to a decision by Parliament, barbers in England were only allowed to perform bloodletting , pull teeth and care for the hair. Until 1745 the surgeons' associations existed parallel to the barber's associations. By a decision of the British King George II , the associations were separated and the barbers could devote themselves to hair care. The French King Louis XV. made the same decision a few years later.

In 1858 the Odontological Society of Great Britain and then the Institute of Dentists, i.e. the dentists of England, were founded. The dentists Horace Hayden and Chapin A. Harris founded the first dental school in Baltimore (USA) in 1840. In the same year, the important American Society of Dental Surgeons and in 1845 the French Société de Chirurgie dentaire de Paris , whose first president was the Parisian doctor and especially dentist Louis Nicolas Regnart (1780-1847) was. In 1859 the London School of Dentistry was founded. The first exam also took place this year. Registration was introduced for licensed dentists in 1878 and control of those who were not licensed in 1921.

In Belgium , the first statutory provisions governing the practice of dentistry can be established in 1818, including an examination by a Provencial Commission. New regulations followed from 1880. In 1815, only a kind of examination before the medical supervisory authority took place in Sweden. In 1860, the Svenska Tandläkaresellskapet (Swedish Dental Association) was founded in Sweden and in 1885 a polyclinic was created as a teaching institution. Dental treatment in Russia was born around 1760–1770, when the German Obel was one of the first dentists to be awarded the right to practice after an examination at the Medical College in Saint Petersburg . According to a law published in 1810, these foreign specialists had the right to train pupils in a manual manner who, after passing an examination, worked as dentists.

In 1779 the barbers and bathers were united by the German imperial laws. On May 25, 1804, the Danish king issued the “276. Patent for the establishment of a medical college ”. The new Prussian trade legislation abolished the guilds in 1811 and the practice of surgery was separated from the barber trade. As a result, surgery was able to develop independently of the barber / hairdressing trade, especially after freedom of establishment for healers was introduced in 1818.

In Germany, dentistry and other medical-surgical subjects were unworthy of an academically trained doctor. Barbers took over most of the dental care of the population. According to Grosch, the job title Bader was the same in southern Germany as a barber was in northern Germany. However, both guilds could exercise different functions, depending on the region and time period. They gave themselves a wide variety of job titles, such as dental technician, dental artist, dentist, dentist, dental surgeon, dentist licensed in America, doctor, doctor, dentist, specialist for dentists, docent, teacher of modern dental technology, American doctor of dental surgery, Swiss dentist or traded as Atelier for dental operations or dental atelier . Beside them the tooth breakers were out and about at fairs.

The barbers tried to meet the demand for lighter teeth with aqua fortis (nitric acid). However, it should take to 1989, to a method of bleaching ( engl .: Bleeching) to VB Haywood and Heyman by means of hydrogen peroxide (H 2 O 2 found) distribution.

Johann Andreas Eisenbarth (1663–1727), a highly privileged medicus from Magdeburg , “cured” the people in his own way. In Bavaria, such a vagabond doctor, with official permission, drove his mischief until 1772, even longer without permission. In Saxony , under Friedrich August II. (1696–1773), the Collegium medico-chirurgicum was opened in 1748, three years later the first surgical clinic, where a teacher of dentistry was also employed in 1777.

At the beginning of the 18th century, technical terms that had disappeared were in use in modern times. The names for tartar were tartar , Tartarus dentium (after Paracelsus Tartarus , "deposits and concrements") or Odontolithus (Greek: ὀδόντ- odont- "tooth"; λίθος lithos "stone"). When a tooth was "burned out", the tooth pulp was treated with a hot probe. The "filing" of a tooth was used to remove caries from the tooth so that the caries would not spread any further. This created unsightly gaps between the teeth, which were avoided by only filing the teeth distally (backwards) and adding a filling material to the filed teeth. An abscess was opened by “scarifying the gums” ( cupping ) .

In addition to numerous tooth wash, tooth tinctures and JA Rieses's widow tooth wool or Kropp's tooth cotton (20% carvacrol cotton ), the silk plaster with cantharids (Emplastrum mezerei cantharidatum, Drouotisches plaster) against toothache, which had to be worn behind the ear, was offered. To produce it, “30 parts of Spanish fly and 10 parts of daphne bark are soaked for eight days with 100 parts of vinegar ether ; 4 parts of Sandarach , 2 parts of Elemi and 2 parts of rosin are dissolved in the filtered tincture and then spread on taffeta that has previously been coated with a solution of 20 parts of isinglass in 200 parts of water and 50 parts of alcohol ”. In 1895 “ amber tooth pearls for teething children” were offered, which were touted as “more effective than tooth collars”.

On December 1, 1820, the medical college in Kiel issued the fee schedule for all medical professions. Since the barbers were also authorized to pull teeth, they could fall back on the dentists' tax .

Since the beginning of the 19th century, the barbers developed more and more into the profession of hairdresser . With the new journeyman's examination regulations of March 20, 1901, the separation between hair and healing arts took place. The job title “barber” finally disappeared in 1934. However, they were still allowed to pull teeth until the Dentistry Act was passed in 1952.

Recourse to ancient teachings, Arab-Persian influence, new assumptions

The acceptance and revival of ancient notions of illness and treatment methods in Christian Europe took place via Salerno . The school in Salerno, supervised by the Benedictines , was one of the first medical universities in Europe and integrated specialist knowledge from the Arab, Greek, Jewish and Western-Latin cultures. Thus, at the beginning of their appearance, the monasteries took on a social task for the general public, with Constantinus Africanus (1017-1087) being of central importance. He translated Arabic compendia into Latin, making them accessible to scholars. On the one hand, the humoral pathology of antiquity, which attributed toothache to juices flowing downwards, and on the other hand, the idea of a divided lower jaw. Constantinus recommended an arsenic application to combat toothache. The use of arsenic to treat a sore tooth in Chinese healing art is said to have been described by Huang-Ti (黃 鈦) in his work Net Ching as early as 2700 BC . The Chinese knew nine causes of toothache (Chinese: Ya-Tong ) plus seven forms of gum disease. In contrast, they used acupuncture , the technique of which was described on 388 pages, including 26 pages of acupuncture measures for toothache.

In Liber Regius , published in the middle of the 10th century, the Persian doctor Haly Abbas (ʿAli ibn al-ʿAbbās; † 944) also recommended the use of arsenic for devitalization (dying) of the pulp. Arsenic (III) oxide was used until modern times to devitalize the tooth pulp and disappeared from the range of therapies in the 1970s because of its carcinogenic effects, inflammation of the gums , the loss of one or more teeth including necrosis of the surrounding alveolar bone , allergies and symptoms of poisoning.

A few references to the treatment of tooth and gum problems can be found in the greatest Jewish scholar of the Middle Ages, Maimonides (1135 / 38–1202). He could only refer to a few Talmudic passages. One of them forbids a priest ( Kohen ) to worship if he is missing teeth, as such a Kohen is unsightly. At the same time, the importance of teeth from the Bible quote eye for eye becomes clear ( Hebrew : עין תּחת עין ajin tachat ajin), often quoted as "an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth". With reference to the Codex Hammurabi , the partial quotation is usually understood to mean that the perpetrator should be rewarded with the same with the same. However, the biblical context of the Torah contradicts this interpretation. According to the predominant rabbinical and historical-critical view, it is about appropriate compensation ( Talion formula ), which is to be paid by the perpetrator in cases of bodily harm . ( "If an eye is lost, replace what is worth to the eye, if a tooth is lost, what is worth to the tooth - eye for eye, tooth for tooth." ). This was intended to contain the blood feud that was widespread in the ancient Orient and to replace it with a proportionality of offense and punishment.

The School of Salerno produced Roger Frugardi , who wrote articles on dentistry, and Gilbertus Anglicus († 1240), who differentiated between two causes of toothache, namely weak teeth and bad juices and food particles between the teeth.

Another region through which Arabic knowledge found its way north was the Toledo School of Translators . The Qānūn fī ṭ-Ṭibb ( Arabic القانون في الطب, Canon of Medicine) of Avicenna as a template for surgeons such as Bruno da Longoburgo , Teodorico Borgognoni or Wilhelm von Saliceto . The term wisdom tooth is derived from Avicenna's translation into Latin as dentes intellectus . The work, of which 15 to 30 Latin editions existed throughout the West in 1470, was considered an important textbook in medicine until the 17th century. In the Arab Empire, ancient Greek scriptures were translated into Arabic and formed the basis of the healing arts, which were supplemented by the rules of the Koran . In Toledo, Saliceto again adopted the treatment methods derived from the prescriptions of the Koran in his translations from Arabic into Latin, which, however, imposed considerable restrictions on anatomy and surgery. The shedding of blood was forbidden in Islam, so developed one bloodless there treatments: caustics were to tooth extraction previously applied to the gum to the tooth by the subsequent inflammation of the periodontal apparatus was loosens enough that it by hand - without bloodshed and thus " “- could remove. This correlated with the above-mentioned edict of Pope Alexander III that bloody interventions were incompatible with the priestly office. However, Bernhard von Gordon warned against appropriate treatment of the front teeth. He also recognized in his Lilium medicinae (around 1303) that chewing on one side led to tartar and plaque formation on the unused side. The fixation of a fractured lower jaw on the intact upper jaw ( intermaxillary fixation ) can also be traced back to Saliceto. It was not until the 19th century that this idea was taken up again and further developed.

Abu l-Qasim (936–1013), known in the West as Albucasis , attests to Kitāb at-Taṣrīf ( Arabic كتاب التصريف) his extensive knowledge and skills in tooth surgery, tooth stabilization with gold and silver wire and in the treatment of gum problems, including dental prophylaxis. Abulcasis perfected many dental instruments, as can be seen from his sketches.

About 500 years later Ambroise Paré (1510–1590) wrote numerous and widespread articles in French, and thus also non-academically trained surgeons and barbers, understandable language on dental treatment. Paré considered the principles that superfluous items had to be removed, a rotten tooth extracted and missing parts replaced (reimplanted) to be important. He developed stabilizing ligatures for jaw fractures, experimented with reattaching chipped teeth and designed simple, fixed dentures. He coined the term "obturator". Obturators were used to close defects in the palate, which were often a result of tertiary syphilis . They were made of leather, silver, ivory, or a sponge attached to a metal holder.

Guy de Chauliac listed various extraction instruments such as levers and forceps in his Chirurgia Magna of 1363, but otherwise referred to Avicenna and Abulcasis. Like him, he mentions the dentures made from bovine bones. He also confirmed that barbers and traveling tooth breakers performed most of the extractions. Despite various other writings, the medieval-ancient tradition lasted until the 18th century.

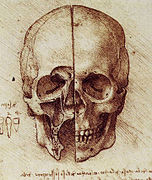

anatomy

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1512) made the first modern anatomical drawings of the jaw, teeth and masticatory muscles . He also created sketches for the anatomy of the face and the maxillary sinus. One of the founders of anatomy was Andreas Vesalius , who with his anatomy De humani corporis fabrica libri septem of 1543 questioned the views of the ancient authority Galen of Pergamon. Vesal relied on the dissection of human corpses for his anatomical findings, which founded modern anatomy , while Galen gained his (incorrect) knowledge by dissecting animals. It was through him that the joint ligaments and inter- joint cartilage of the temporomandibular joint were first described . He also discussed the function of the muscles of the face and cheek in great detail, gave an exact anatomy of the tooth roots and was the first to recognize the pulp cavity , but not its function. Bartolomeo Eustachi (1500 / 1513–1574) was the first to examine the first and second dentition in more detail and, in 1550, also described the function of the pulp cavity.

Vesal's successor, Gabriele Falloppio , recognized the morphological independence of the two sets of teeth , who was also the first to name the tooth follicle. The first dental treatise in German, largely independent of other medical disciplines, was published by Walther Hermann Ryff around 1548 in Würzburg.

histology

In the 16th century, in contrast to Vesal and his acquaintances Eustachi and Falloppio , Volcher Coiter no longer interpreted the tooth as bone. In the pre-microscopic era of the 16th and 17th centuries, in addition to Bartholomaeus Eustachius, Marcello Malpighi (1628–1694) and Johann Jakob Rau (1668–1719) researched the structures of hard dental tissue and their origins. With the development of optical magnification aids, especially by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723), more precise histological examinations of the tooth structure and discoveries in the area of the histological processes during the embryonic phase of the teeth are possible. Malpighi postulates the secretion theory of melt formation by means of an ossifying juice; Eustachius mentions the conversion theory for the first time. Alexander Nasmyth (1789–1848), Richard Owen (1804–1892), Anders Adolf Retzius (1796–1860), Jan Evangelista Purkyně (1787–1869), Albert von Kölliker (1816–1905), Wilhelm von Waldeyer (1836–1921 ), Viktor von Ebner-Rofenstein (1842–1925), Gustav Preiswerk (1866–1908), John Tomes (1815–1895) as well as his son Charles (1846–1928) and many other researchers gave dental histology a thorough study of the the entire area has a broad scientific basis.

So far, only a few studies have been carried out on medieval corpses in order to determine , for example, periodontal pathogens. As part of a study, it was possible to isolate and decipher large amounts of genetic material from the tartar of a 1000-year-old skeleton . It is tartar from a man who lived in Dalheim Monastery (Lichtenau) . Substantial parts of the genome of a periodontal bacterium could be reconstructed, and the genetic material of food components was found for the first time, including 40 opportunistic pathogens , antibiotic resistance genes , the genome of the periodontal pathogen Tannerella forsythia was successfully reconstructed from 239 bacterial and 43 human proteins . The discovery paves the way to a better understanding of tooth and gum disease and shows how the human oral flora and common diseases have developed and adapted in human evolution.

Changes were only introduced again through Pierre Fauchard.

Protagonists of dentistry in the 17th and 18th centuries

While academically educated doctors described physiological and anatomical conditions in their publications, the practical practice of dentistry in the 17th century was mainly practiced by barbers, tooth breakers, barkers and quacks. In the 18th century, independent dentistry developed and, as a result, an increasing establishment of the dental profession, especially in the larger European cities. However, recognition as an academic subject began only gradually in the 18th century.

Pierre Fauchard

Dentistry was first introduced in Europe as an independent medical discipline in France. Louis XIV. (1638–1715) issued the edict Expert pour les dents (“Specialist for teeth”), which forbade the barbers to extract teeth and introduced a profession of surgeon dentiste , the “dental surgeon”, which was equal to the surgeon . As a result, Pierre Fauchard (1678–1761) published the book Le Chirurgien Dentiste ou Traite des dents ("The dentist or the treatment of teeth") in 1723 . With this publication, Fauchard is regarded as the father of modern dentistry. His book was the first to provide a comprehensive description of dentistry, including the basics of oral anatomy and functioning, as well as surgical, conservative, and prosthetic treatments. His thoughts were completely new. He rejected the cause of tooth decay, which he called the “German toothworm theory”, as wrong. He often looked through a microscope and found no worms. Sugar harms both gums and teeth. One should limit the consumption of sugar in daily food. The milk teeth seem to separate from their roots. However, it is wrong for some dentists to claim that they have no roots. (The false claim was based on the fact that deciduous teeth no longer have roots because they are resorbed before the tooth change.) The first authentic case report of a homoplastic tooth transplant (from person to person) was written in 1728 by Pierre Fauchard. In 1746 he first described the clinical symptoms of periodontitis . In 1889 Théophile M. David (1851-1892) suggested naming the disease described as "Maladie de Fauchard" after its author. It was known especially in the Anglo-Saxon-speaking area as Rigg's disease (English: Riggs disease), after the American dentist John Mankey Riggs ( see below ).

Fauchard recommended lead, tin or gold for filling carious teeth. Teeth should be cleaned regularly by a dentist. He described tooth alignment, recommending that if the teeth were irregularly positioned, creating space between them by filing, loosening the teeth with tweezers, and using wires to fix the teeth in their new position until they became firm again. If a tooth is knocked out, it can be replanted ( replanted ) and it will still be able to serve for many years. He was a vehement opponent of dental charlatans and criticized their unsuitable or fraudulent procedures.

For example, he refused to allow nitric acid and sulfuric acid to be applied to the teeth to remove tartar , which would only seriously damage the teeth and subsequently have to be extracted. Fauchard criticized the use of horsehair in toothbrushes, which were too soft to be able to remove plaque, and instead called for the toothbrushes made from pig bristles, which had been used in China since the beginning of the 16th century, to be used or cleaned with a sponge or cloth. Around 1700 Christoph von Hellwig invented a toothbrush in its current form. With the invention of nylon in 1938, the US company DuPont manufactured the first nylon toothbrushes.

He also revealed that charlatans filled teeth with cheap tin or lead , only covered them with a thin layer of gold, and sold them as expensive gold fillings . Gold leaf to replace hard dental tissue was used in the Arab world as early as the eighth century. The first written references in Europe to gold foil as a filling material for teeth were not found until the middle of the 15th century. In 1484 Giovanni d'Arcoli first used gold foil as a filling material for carious teeth. The gold hammer filling in a molar (molar) is documented in the case of Anna Ursula von Braunschweig-Lüneburg , who was buried in 1601 . At that time, in contrast to the modern age, the gold filling was not cast from liquefied metal, but instead was placed using cold welding . This is based on the property of gold in a highly pure state to form atomic bonds at its interface and thereby harden. The gold foil is tapped (condensed) into the tooth with a hammer (hence the name). The gold hammer filling experienced an upswing in the United States in 1855 by Robert A. Arthur and William Gibson Arlington Bonwill and has been used as a filling process up to modern times, as it is a restoration technique that is gentle on the tooth substance.

The smile revolution

In his book The Smile Revolution in Eighteenth Century Paris , Colin Jones describes that in those days the smile that made teeth visible was frowned upon, especially at court. Small-lipped smiles were required as part of physical control to survive in the world of the royal court of Louis XIV (1638–1715). It was also a social characteristic: no courtier wanted to be seen with his mouth open, let alone portrayed. Tooth gaps and ugly dark teeth were widespread, especially because of the decadent lifestyle and the high-sugar diet. But smiling was also seen as a sign of gullibility, recklessness or bad manners, in the worst case a mark of a madman. In the 18th century, however, the literary works and stage works by Samuel Richardson (1689–1761) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) caused a change of heart. Richardson's work established the school of sensitive literature . Emotions should be shown through a charming smile, but this was only possible for the social and cultural, wealthy elite who could afford expensive dental treatment. Teeth and dentists became “chic”, which was mainly due to Fauchard's special expertise. He was able, at least in part, to replace the brutal tooth breaker methods customary at the time and devoted himself to tooth preservation and prevention. Nicolas Dubois de Chémant made expensive dentures with porcelain teeth ( see below ).

In autumn 1787, visitors to the exhibition would have loved to sink into the ground when they saw a self-portrait of the important artist Marie Louise Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755–1844) on the walls of the Louvre . The problem was her mouth. He smiled - not just like the Mona Lisa's enigmatic smile , but with a smile that showed her teeth. “Was Vigée Le Brun crazy, a slut or some kind of revolutionary gone mad?” The only thing left for the visitors was to pretend they hadn't noticed anything. However, with the French Revolution (1789–1799), the “Parisian smile” became increasingly widespread in many variations. However, it was soon suppressed by terror and turned into a smile of resignation, up to the desperate smile of the victims on the scaffold . Smiling was no longer an expression of openness, but made people suspicious. People lost their smile and with it the dentists - also through some "reforms" - were pushed to the margins of society and lost their reputation. The “smile revolution” came to an end.

Philipp Pfaff

Fauchard's counterpart in Germany was Philipp Pfaff (1713–1766), who published the first textbook on dentistry in German in 1756: Treatise on the teeth of the human body and their diseases . He described, among other things, the molding of the jaw with sealing wax , whereby the impression , which was first cast with plaster, served as a model for the production of dentures . In 1840, the Americans L. Gilbert and WH Dwinelle accelerated the setting of the plaster by adding salts, thus transforming it into a suitable impression material. As a result, plaster of paris was used for functional plaster casts in toothless patients.

The "direct capping", a covering of the vital (living), opened tooth pulp (tooth nerve) with gold plates, goes back to Pfaff. He also published the first description of an extraoral retrograde root canal filling in the context of tooth replantation . The root canal of the extracted tooth is closed from the tip of the root and then the tooth is replanted (replanted). Pfaff was appointed court dentist by Frederick the Great . The Philipp Pfaff Institute , the joint advanced training academy of the Berlin Dental Association and the Brandenburg State Dental Association , is named after him.

John Hunter

In England, the Scot John Hunter (1728–1793), a surgeon and anatomist who is considered the founder of scientific surgery , wrote in 1771 The Natural History of the Human Teeth (translated from English: John Hunter's natural history of teeth and description of diseases . […] Leipzig 1780) and 1778 A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of the Teeth ("A practical treatise on the diseases of the teeth") with for the first time scientifically detailed descriptions of the anatomy , physiology and pathology of the teeth. Much of English society has been hostile to Scots since the Second Jacobite Rising. In this situation, Hunter had no choice but to turn to the job of the lowest esteem among medical professionals and commonly practiced by quacks and barbers: that of dentist. He wrote the most extensive treatise on dentistry of that time. One of the things Hunter was interested in was the transplantation of teeth. However, he overlooked the fact that in numerous cases infectious diseases, especially syphilis, were transmitted through transplantation . He believed that this was only possible with purulent teeth. Numerous dental practitioners then developed various requirements that a tooth donor had to meet in order to minimize the transmission of diseases. Tooth transplantation was already carried out by the ancient Egyptians, later also by the Etruscans, the Greeks and the Romans. The first written evidence is found in 1594. In 1685, Charles Allen ( York ) made detailed statements on heteroplastic tooth transplantation (from animal to human), including a description of how the animal had to be tied up. It was the first dental booklet to appear in the English-speaking world and containing astonishing insights into anatomy and physiology. In the 1930s, the healing of transplanted teeth was examined histologically by Heinrich Hammer (1891–1972) for the first time . Healing only occurs if the Desmondont (root skin) is completely preserved , otherwise the graft first heals in the bone and is then resorbed . Hunter also conducted research in the field of orthodontics ( see below ) and suggested removing the tooth pulp before filling therapy for carious teeth . He also dealt with the treatment of anomalies in tooth position .

James Lind

Scurvy (English: Scurvy ) was since the 2nd millennium BC. Known as a disease in Egypt. Later Hippocrates and Pliny also wrote about it. In addition to other serious symptoms, bleeding gums and gingival hyperplasia occur. The disturbed collagen synthesis leads, among other things, to a reduced synthesis of the Sharpey fibers of the teeth holding apparatus (periodontium), which mainly consists of collagen , which leads to tooth loss . If there is a persistent lack of ascorbic acid (vitamin C) in the diet, the disease occurs after about four months and, if left untreated, leads to death.

In the Age of Discovery , from roughly the 15th to the 18th centuries, scurvy led to the mass deaths of seafarers ; For example, the ship of Vasco da Gama lost about 100 men to scurvy on a voyage of 160 men. The reason for the frequent occurrence of scurvy at sea was the unbalanced diet, which - due to the lack of preservation options - mainly consisted of salted meat and ship's rusks. In 1734 the theologian and physician Johann Friedrich Bachstrom demanded the use of fresh fruit and vegetables to cure scurvy. That citrus fruits against scurvy help was at least since 1600 known as a doctor of the East India Company had recommended for this purpose, but their use had not initially enforced. It wasn't until the British ship's doctor James Lind was able to show in 1754 that citrus fruits help against scurvy that the disease lost its horror. Lind was the first to investigate its effect in a systematic experiment from 1747. It is one of the first controlled comparative studies in the history of medicine. For his experiment he divided twelve scurvy-sick sailors into six groups. All received the same diet and the first group also received a quart (a liter) of cider daily. Group two took 25 drops of sulfuric acid , group three six spoons of vinegar , group four half a pint (almost a quarter liter) of sea water, group five two oranges and a lemon and the last group a spice paste and barley water . Treatment of group five had to be discontinued when the fruit ran out after six days, but by that point one of the sailors was already fit for duty and the other was almost recovered. In the other test participants, a certain effect of the treatment was only seen in the first group. Scurvy also occurred on land, especially in the winter months , in besieged fortresses , in prisons or among the first North American settlers, where fruit and vegetables were initially scarce. In the 20th century, scurvy occurred en masse during the First and Second World Wars as well as in German concentration camps and in the Soviet gulag .

The name ascorbic acid (previously hexuronic acid ) was derived in 1933 by Albert von Szent-Györgyi Nagyrápolt and Walter Norman Haworth from the Latin name of the disease scorbutus , with the negative prefix a- (weg-, un-) - "anti-scorbutic acid". In 1934, the pharmaceutical company Roche was the first company to start synthetic production of vitamin C to combat this vitamin deficiency disease . As recently as 1936, Roche employees reported that the specialists among the doctors simply rejected vitamin therapy; 80 percent would even laugh at the "vitamin craze". At the time, an internal company letter stated that “the need for vitamins in the first place” had to be created. Vitamin C is only taken regularly "when something hocus-pocus is being made". The National Socialists then very actively promoted the supply of vitamins to the population in Germany. They wanted to "strengthen the national body from within" because they were convinced that Germany had lost the First World War as a result of malnutrition . In 1944 the Wehrmacht ordered 200 tons of vitamin C from Roche, among others.

Other protagonists from the 17th to the 19th century

In France, Italy and Spain in particular, further works were published which dealt with dentistry in whole or in part:

- Jacques Guillemeau (1549–1613), Les Œuvres de chirurgie, 1602

- Wilhelm Fabry von Hilden (1560–1634), city doctor and surgeon in Bern, described the removal of jaw tumors.

- Pierre Dionis (1643–1718), Cours d'operations de chirurgie, 1707; several editions.

- Johann Scultet (1595–1645), L'arcenal de Chirurgie, 1712

- Étienne Bourdet (1722–1789), Recherches et observations sur toutes les parties de l'art du dentiste, 1757

- Antonio Campani (1738–1806), Odontologia ossia trattato sopra i denti opera, 1786

- Félix Pérez Arroyo, (1755–1809) Tratado de las operaciones en la dentadura, 1799

- Louis Laforgue, (? –1816), L'Art du dentiste ou Manuel des opérations, qui se pratiquent sur les dents, Paris 1802

- Jean-Baptiste Gariot (1761–1835), Traité des maladies de la bouche, 1805

- Joseph Fox (1755-1816), first instructions on dental regulations, which were followed in England until about 1850.

- J.-CF Maury (1786–1840), Traité complet de l'art du dentiste d'après l'état actuel des connaissances, 1828

- Jakob Calmann Linderer (1771–1840), teaching of all dental operations based on the best sources and his own forty years of experience. Berlin 1834; Reprint Bremen 1981

- Joseph Linderer (* 1809, Jakobs Sohn), Jakob Calmann Linderer: Handbook of Dentistry, containing anatomy and physiology, materia medica dentaria and surgery, Berlin 1837

- Joseph Linderer: The preservation of one's own teeth in their healthy and diseased condition, Berlin 1842

- Pierre-Joachim Lefoulon, (? –1841), Nouveau traité théorique et pratique de l'art du dentiste, 1841

- Edmond Andrieu (1833–1889), Traité de dentisterie opératoire, 1889

Basic research

Only when anatomy and physiology had made corresponding advances in basic research could dentistry gradually become an independent science in the 19th century. These include primarily the relevant microscopic examinations by Jan Evangelista Purkyně (1787–1869), Anders Adolf Retzius (1796–1860) and Albert von Kölliker (1817–1905).

In 1782, Johann Jakob Heinrich Bücking introduced the first specialized pliers for the various applications. Extraction forceps go back in their current form to the English oral surgeon John Tomes (1815–1895). The Tomes fiber , discovered by him in 1840, is named after him, the cell extension of an odontoblast ( dentine former), which is located in the dentinal tubules . He was elected first President of the British Dental Association because of this and other contributions to dentistry .

Historical forms of treatment

Reconstructive dentistry

There is evidence that dental amalgam was used as a filling material as early as the beginning of the Tang Dynasty ( Chinese 唐朝 , Pinyin táng cháo ) in China (618–907 AD) , as described in the writings of the Chinese doctor Su Kung (蔌 哭嗯) from the year 659. Amalgam returns as a “silver paste” in Ta-Kuan Pent-ts'ao (大观 被 压抑 的 曹操) around 1107. The alloy is also mentioned in 1505 and 1596 (by Li Shi-Zhen李时珍) in the Ming period ( Chinese 明朝 , Pinyin míng cháo ) . In 1505, Liu Wen t'ai (刘 雯 台) describes the exact composition: "100 parts of mercury , 45 parts of silver and 900 parts of tin , to be stirred in an iron pot."

Although special treatises in the local language on dental treatment have been available since the 14th century, "the Ottinger", named after a dentist, has been documented in technical literature since the 15th century. In 1530 the Mittweidaer Zene Artzney Buchlein against all sorts of kranckeyten and frailties of the tzeen was published , a "small healing book for all kinds of diseases and ailments of the teeth", the first book that is entirely devoted to dentistry, written for barbers and surgeons who use the mouth to treat. It covers topics such as oral hygiene , tooth extraction , drilling the teeth and making gold fillings . It contains advice on “how to help the children so that they can easily venture into [them] ir zene”: The little ones should be bathed frequently and then the gums with a finger that has previously been dipped in warm chicken, goose or duck fat has been, "subtle rubbing and trucking". When the teeth break through, one takes “fine, subtle” wool from the neck of a sheep, dips it in warm chamomile oil and then places it on the baby's neck and cheeks. Sometimes people tried to make "difficult" teething easier by hanging a greased bat around the child's neck. However, as in the High Middle Ages, the direct application of fat was probably more common.

One of the first dental monographs is the so-called “useful report” by Walther Hermann Ryff from 1548: a useful report on how to keep the eyes and face, where they are lacking, dark or dark, sheared, healthy, stiffened and confirmed. […] With further instruction on how to keep the mouth fresh, pure, clean, healthy, strong and firm […] .

Those who could not afford gold were usually filled with lead (from the Latin plumbum “lead” the terms plombe and plombieren derive ) or - less permanently - from the resins galbanum or opopanax .

Since the lead was too soft, the search for a durable material continued. The amalgam was rediscovered in Germany and used for the first time in 1528 by the Ulm doctor Johannes Stocker , who in his pharmacopoeia Praxis aurea describes the production of amalgam, which "hardens like stone in a tooth hole". However, amalgam did not see its introduction in the western world until the 1830s. In 1806, Joseph Fox (1755–1816) still used an alloy of bismuth, lead and tin (an alloy studied by the chemist d'Arcet, the " Darcet's metal "). The Parisian dentist Louis Nicolas Regnart (1780–1847) suggested in 1818 that this alloy be introduced into the tooth hole (the cavity to be filled) in small pieces and melted there with a hot plug. By adding a tenth of the mass of mercury, Regnart was able to lower the melting point considerably. Initially, amalgam was made by mixing mercury with a filing made from silver coins. In 1819 Auguste Onésime Taveau introduced the amalgam in France and Thomas Bell in England. As early as 1833, after the forced introduction of amalgam as a filling material by Crawcorn, who had brought it with him from Europe in 1830, the so-called "amalgam war" broke out, which led to a temporary ban on amalgam as a filling material. The time went down in history as Crawcorn days . In 1855, two American dentists, William M. Hunter (1819–1889) and Elisha Townsend (1804–1858), announced a new amalgam formulation that came close to that of modern times. The powder mixture consisted of four parts of silver and five parts of tin; one gram of mercury was processed per gram of this powder. However, any dentist who processed amalgam was expelled from the American Society of Dental Surgeons, leading to the dissolution of this association in 1856. A similar discussion flared up in Germany in the 1920s. During this debate, which has now dragged on for almost two hundred years, no major health hazard could be demonstrated.

The Paris court dentist Antoine Malagou Désirabode described in 1845 in the chapter "De l'obliteration ou plombage des dents" of his book on the art of the dentist a tooth filling that is based on a principle from the construction industry ( fluation ). The fact that fluoride and fluorosilicates (then called "fluate") bind moisture and harden in the process, made them appear suitable as dental fillings when mixed with aluminum oxide. Soon after, there were numerous patents for dental fillings with fluoride additives.

On March 20, 1860, the American dentist Barnabas Wood (1819–1875) received a patent for a low-melting alloy. Wood's metal , named after him, was also used for dental fillings, despite the content of the toxic heavy metals lead and cadmium . The components bismuth , lead, cadmium and tin are ignoble and easily dissolve in the mouth, so that there is a risk of chronic cadmium poisoning . Therefore, the alloy soon disappeared again as a dental filling material.

In connection with amalgam fillings, Greene Vardiman Black drew up Black's rules for cavity preparation, named after him, in 1892, including the principle of extension for prevention ( English: expansion [of the cavity] for prevention). As a result, the tooth should be drilled so far that the filling margins were relocated to an area that is easily accessible for cleaning. He also divided the cavity shapes into five cavity classes , which have retained their global importance to this day. He changed the composition of the filing, which now consisted of 68.5% silver, 25.5% tin, 5% gold and 1% zinc to increase strength. Black also invented the phagodynamometer for measuring chewing pressure, which was presented to the professional world in 1895.

Aesthetic and ritual tooth corrections

The specialty of ethno-dentistry deals with the various procedures of tooth changes. The first dental work was done by the Etruscans and Phoenicians (now Lebanon) in the middle of the first millennium before the turn of the century. The Etruscans (now northern Italy) were able to produce gold spheres 0.1 mm in diameter and connect them to one another without soldering. Their metallurgists had the following recipe: "If you mix the juice of three types of vegetables and charcoal dust with gold particles, tiny gold pearls form as if by magic." The illustration on the right shows human or animal replacement teeth that are attached to a gold band with a metal pin the remaining teeth were attached. They knew that saliva did not attack gold. Women and men were equal. Slaves were also allowed to wear elegant clothes and gold jewelry. Dentistry was in the hands of doctors.

Artificial deformations have been made for thousands of years - always in a ritual or cultural context. Depending on the respective peoples, a distinction is made between different types of deformation: There are pointed, gap, surface or serrated filing of the teeth, horizontal filing up to complete sawing of the tooth crown. In addition, there are furrow, cell and relief filings, the displacement of front teeth from their natural position, the creation and enlargement of diastemas or gaps, the breaking out or levering out of single or multiple teeth with a spear point or stone chipping, the elongation (apparent lengthening) medium Front teeth, the dental jewelry and the artificial coloring of the teeth.

A dental bridge consisting of five human teeth attached to a gold ribbon was discovered in a tomb of the monastery of San Francesco in the Tuscan city of Lucca in Italy . The 17th century dental bridge is similar to the Maryland bridge (adhesive bridge or adhesive bridge) developed at the University of Maryland in the 1970s. The prosthesis found consists of three central incisors and two lateral canines attached to a golden band. Two small gold pins attached the teeth to the band.

Tooth blackening

In Japan, tooth blackening ohaguro ( Japanese お 歯 黒 ) has been fashionable since the middle of the first millennium, as suggested by traces of blackened teeth in bone finds from the Kofun period (300 to 710). The Ohaguro goes back to the Heian period (794–1192). It was first mentioned in writing in the Genji Monogatari ( jap. D , dt. The story of Prince Genji) in the 11th century, although it has been around since 2879 BC. Was practiced. Was conducted ohaguro of men and women of the court nobility and later by the Samurai . During the Edo period (Japanese 江 戸 時代, Edo jidai, 1603 to 1868) it was common for married women to blacken their teeth. It was considered erotic as it increased the contrast with the white skin of the face. It was therefore very common among women in the brothel district . At the same time it was considered a symbol of marital fidelity. In the 18th century men were banned from blackening their teeth, and in 1871 the Meiji government (Japanese 明治 時代 Meiji jidai) finally extended this ban to women by a cabinet decision , as this practice was classified as barbaric under Western influence. In the Nguyễn dynasty ( Hán Nôm : 家 阮 ) in Vietnam (1802 to 1945) the custom lasted into the 20th century. In Southeast Asia it was a symbol of strength and honesty, was considered a symbol of beauty and signaled the willingness to marry women. An elaborately manufactured mixture of iron filings, which were put in tea or rice wine and oxidized, was used to dye the teeth . The resulting black color was applied to the teeth with a soft brush and adhesive powder . Because of the limited shelf life, the procedure had to be repeated every three days. It was also believed that blackening kept teeth healthy and counteracts any iron deficiency during pregnancy. Recent studies of the composition of the dye confirm that there was a certain protection against tooth decay and demineralization of the teeth.

Gemstones

Around the year 900, for ritual or religious reasons, the Mayans decorated their front teeth with various gemstones such as jade , cinnabarite , serpentinite , pyrite or hematite , which were found during excavations in Antigua Guatemala . For this purpose, holes precisely matched to the size of the gem were drilled with a drill and floating abrasives made of quartz powder . More than 50 different patterns were identified. It is believed that each pattern represented a tribal affiliation or had a religious meaning.

In modern times, Mick Jagger decided to have a ruby inserted into an anterior tooth, but had it exchanged for an emerald in order to eventually replace it with a diamond . This started a trend towards tooth jewelery like twinkles (brillies), dazzlers and grills .

Tooth gold plating

Already 1000 BC The Chinese used tooth fillings made of the finest gold leaf, which was stamped into the caries holes. The first prosthetic work was done in 500 BC. Made by the Phoenicians . In Eastern Europe, for example in Tajikistan and the Orient, gold teeth on the front were considered a sign of wealth.

Urine therapy

Human or animal urine , which is rich in urea and carbamide peroxide , was used in early China for its analgesic properties, healing and teeth whitening. The Huángdì Nèijīng (chin. 黄帝内經) is one of the oldest standard works of Chinese medicine . It is translated as "The Medicine of the Yellow Emperor" ( Huáng Dì , Chinese 黃帝 / 黄帝 ). Two of the 18 volumes are devoted to tooth and gum diseases. In Nei Tching Sou Wen , rinsing with a child's urine is recommended for painful gum disease and bleeding gums. Bernardino de Sahagún (approx. 1500–1590) points out in his writings that the Aztecs put dental care on a level with body care. After rinsing them with cold water and cleaning them with a polishing cloth, they have blackened their teeth with Espiga Negra (a mixture of different plants) or partially rinsed them with urine. Urine was used to clean teeth from the Celtiberians to the ancient Romans to the French high nobility . For example, Marie de Sévigné (1626–1696) wrote in one of her letters to her daughter that she should rinse her mouth with fresh urine every morning and evening, as she had seen many people cured them of toothache and decayed teeth. This application even from the famous Pierre Fauchard ( as recommended). The procedure was to be assigned to folk medicine and not to scientific medicine, although it is still used today as an autologous urine treatment in alternative medicine .

Stomatoscope

The treatment procedures, which became more and more delicate in the 19th century, increasingly required a better view of the treatment area. The Wroclaw surgeon and dentist Julius Bruck (1840–1902) took up the galvano-caustic operation method developed by Albrecht Theodor Middeldorpf (1824–1868) and published his construction in 1865 in the book The Stomatoscope for the x-raying of teeth and their neighboring parts by galvanic incandescent light . Just two years later, based on the same principle, he developed the urethroscope for x-raying the bladder and its neighboring parts . Since then he has been considered a pioneer in endoscopy . He used the "stomatoscope" both for better diagnosis of the oral cavity (Latin stoma ; ancient Greek το στομα, to stoma = mouth, mouth, last opening. See " stomatology ") and by means of diaphanoscopy for caries diagnosis. According to the Dental History Museum in Zschadraß , Joseph Murphy invented the mouth mirror in 1811.

Further therapy methods

Tiberius Cavallo published his book A complete treatise on electricity in 1777 , in which he recommended the use of electricity to treat toothache. For this purpose, he developed a corresponding instrument with which electrical stimuli could be delivered to a tooth in a targeted manner. His ideas have been taken up in modern times and devices for electrical sensitivity testing of teeth were developed, with which the vitality of the teeth can be checked.

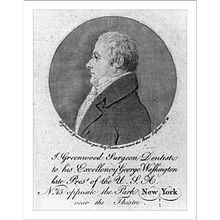

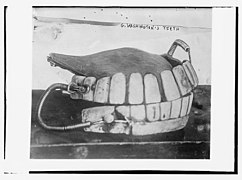

Dental trade and transplants

The Englishman Hunter still believed in the 18th century that a freshly extracted tooth only had to be inserted into another patient quickly enough to be able to grow successfully. With printed advertisements he attracted whole groups of poorer 'tooth donors' who had their healthy teeth extracted for a few pence , so that they could be used immediately afterwards by wealthier contemporaries. Hunter's scientific reputation meant that his ' tooth transplants ' were copied not only in Europe but also in the USA. This method, which was associated with a high risk of infection (especially syphilis ) for patients, was only abandoned towards the end of the 18th century .