Middle Latin

The term Middle Latin summarizes the various forms of the Latin language of the European Middle Ages (around 6th to 15th centuries). An exact differentiation on the one hand from the preceding late Latin (Latin of late antiquity ) and on the other hand from the new Latin of the humanists that emerged in the Renaissance is not possible.

The term is an analogy to Middle High German . The Latin literature of the Middle Ages is a medium-Latin literature refers to the Latin Philology of the Middle Ages as a Middle Latin Philology or shortly Medieval Latin . Professionals in this discipline are known as Middle Latin.

Based on the literary language of the late antique imperial era, the language of jurisprudence and the church fathers , sometimes, but by no means consistently, influenced by the Romance languages or the respective mother tongue of the author, but contrary to common prejudices (" kitchen Latin ") always in contact with the Ancient literature of the classical period, especially poetry , produced an extremely heterogeneous linguistic material that encompasses the whole range from slang , colloquial , pragmatic diction to highly rhetorical or poetic stylization at the highest level and, in its top-quality products, the comparison with the ancient, much stronger There is just as little need to shy away from the literary production filtered by the selection of the traditional process as the one with the simultaneous or later vernacular literary production.

development

When writers dealt with antiquity and Christianity at the beginning of the Middle Ages , only Latin was available to them as a trained written and book language in Romania , that is, in the area in which Latin had established itself as a colloquial language; Romanesque book literatures were only to emerge in the later Middle Ages (from around the 12th / 13th centuries). Even Germania could not come up with a more suitable written language than Latin, especially since the Germanic languages had developed a culture and (mostly oral) tradition that differed from the Mediterranean world. In addition, since the clergyman, who was also the writer at the time, dealt verbally and in writing with the Latin that he found as the language of the Bible , its exegesis , Christian dogmatics and the liturgy , it was obvious that this should be used Language took over as written language.

This Middle Latin differs from classical Latin in numerous ways . The deviations from the classic norm have various causes:

- In addition to Latin as a written and educational language , various vernacular languages have gradually developed in Romania , all of which are further developments of so-called Vulgar Latin . Every author of texts now allows elements of their own mother tongue to flow into their written language. This also applies to people who speak non-Romance languages. The extent of such influences depends, of course, to a large extent on the training of the respective author. Seen as a whole, the vernacular and vulgar Latin influences, especially those that are not conveyed through Bible Latin , are however limited. Therefore, despite some identifiable national peculiarities , Middle Latin does not break down into dialects or regional languages , but has a horizontal structure according to style level and genre. Less pronounced in morphology and syntax , but clearly in word formation , epoch-specific developments can be observed within Middle Latin .

- Since Latin - despite all the linguistic competence and differentiation skills of many writers - is a learned language for everyone , there is a tendency towards gradual simplification (especially in syntax). Typically Latin phenomena are given up or at least used less often, especially if they have already been given up in the Romance languages or do not exist in the respective mother tongue. B. the AcI , the ablativus absolutus and the variety and nesting of the subordinate clauses . The extent to which these tendencies take effect on the individual author is e.g. Sometimes depending on the epoch, very different. Opposing tendencies such as hyperurbanism or mannerism can often be observed.

- The new social and political structures ( Christianity , feudalism ) also affect the language, especially in the area of vocabulary , where numerous new creations are necessary and many words expand their range of meanings .

Throughout the Middle Ages, Latin was a living language that was fluent in the educated classes not only in writing, but also orally, which also included an active mastery of verses and metrics . All those who had a certain level of education were bilingual : on the one hand they spoke their respective mother tongue, on the other hand Latin, which is therefore often referred to as the “father tongue” of the Middle Ages. As already said, the Middle Latin spread far beyond the borders of the Roman Empire , so far as East Germany , Jutland , the Danish islands , after Sweden , Norway and Iceland , in the Slavic areas to the real Russia in and after Hungary and Finland .

The "mother tongue" was expressed in the fact that ancient words were given new meanings, new derivations and words were formed and the language was generally dealt with as with a mother tongue, which is constantly changing , but without ever following the models of the classical era forgotten to which one always remained committed.

The end of Middle Latin was not brought about by the vernacular, but by Renaissance humanism and the so - called Neo - Latin that it gave rise to, which gradually became established in the 15th and early 16th centuries. New Latin was characterized by a stricter orientation to classical Latin . Few classical authors, especially Cicero and Virgil , were considered role models. This backward-looking standardization paralyzed the lively development of language and made it difficult to use the Latin language in everyday life. The virtuosity of some authors disguises the fact that the lack of flexibility in Neo-Latin resulted in overall linguistic impoverishment. The most passionate proponents and lovers of Latin, the humanists, contributed significantly to the suppression of the Latin language through their struggle against what they believed to be barbaric Middle Latin and their insistence on the norms of classical antiquity. It was only during this period that Latin as the language of education and politics began to freeze and “ die ”.

Features of Middle Latin and deviations from Classical Latin

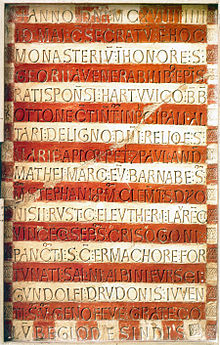

Graphics and Pronunciation (Phonology)

The representation of the phonetics of Middle Latin encounters considerable difficulties for three reasons, firstly the period of around 1000 years, during which there were considerable changes, secondly the spatial extent over large parts of Europe and the associated regional influence from the most diverse in vernacular languages used in this area and, thirdly, the difficulty of reconstructing them exclusively from handwritten evidence and interferences with vernacular languages. Under these circumstances there could not be a uniform debate. Nevertheless, some general statements can be made.

- The phonetic coincidence of the diphthongs ae with ĕ and oe with ē , which has already been documented for the ancient colloquial language, led to orthographic consequences early on. The a is initially subscribed, especially in italics , later the so-called e caudata develops , the e with a tail as descender (ę). Since the 12th century æ and œ have mostly been represented by a simple e , e.g. B. precepit for præcēpit, insule for īnsulæ, amenus for amœnus. In addition, there are reverse (" hyper-correct ") spellings such as æcclesia instead of ecclēsia, fœtus instead of fētus and cœlum instead of cælum. The humanists revive the e caudata , which had temporarily disappeared .

- In early medieval Latin in particular, e and i are often exchanged.

- y instead of i and œ is found not only in Greek words, but also in Latin, z. B. yems for hiems, yra for īra ; see. the title Yconomica (Œconomica) Konrad von Megenberg .

- h is omitted or added, initially, e.g. B. iems for hiems, ora for hōra and hora for ōra, and otherwise, e.g. B. veit for vehit; especially after t, p and c, z. B. thaurus for taurus, spera for sphæra, monacus for monachus, conchilium for concilium and michi for mihī.

- Since t and c coincided before the semi-vowel i , they are very often interchanged in writing, e.g. B. tercius for tertius , Gretia for Græcia.

- Consonant gemination is often simplified or set abundantly, e.g. B. litera for littera, aparere for apparēre and edifficare for ædificāre.

- Inconvenient groups of consonants are simplified, e.g. B. salmus for psalmus, tentare for temptāre.

- Dissimilations are very often and obviously taken from Vulgar Latin , e.g. B. pelegrinus for peregrīnus (cf. in German pilgrims; also French pèlerin , Italian pellegrino ), radus for rārus (cf. Italian di rado ).

- All vowels are articulated openly. Evidence is a holdover in Italian: The Credo in the sense of the Christian creed is articulated with an open 'e' and continues the Middle Latin pronunciation. In contrast, the purely Italian verb form credo ("I believe") is spoken with a closed 'e'.

morphology

conjugation

- Confusion of "normal" verbs and depositions , e.g. B. (ad) mirare instead of (ad) mīrārī, viari instead of viāre (= travel).

- There are numerous conjugation changes, e.g. B. aggrediri for aggredī, complectari for complectī, prohibire for prohibēre (see Italian proibire ), rídere for rīdēre (see Italian ridere ) and potebat for poterat (see Italian potere ).

- In the future tense there are confusions between b- and e-future tense, e.g. B. faciebo for faciam, negam for negābō.

- The passive perfect is very often formed with fui instead of sum : interfectus fuit (from this usage, which incidentally comes across in classical Latin to denote a state in the past, the French passé composé or the Italian passato prossimo developed).

- Additional periphrastic verb forms: The paraphrase with habēre and past participle perfect passive (e.g. lībrōs perditōs habenō ), used in classical Latin only to expressly denote a permanent state, can replace the usual perfect passive or active; dicēns sum .

declination

- There is a certain uncertainty in dealing with the different declensions, so that words sometimes go from one declension to the other, e.g. B. noctuum for noctium, īgnīs for īgnibus . More often the pronominal dative ending -ī is replaced by -ō : illō for illī. In general, there is a tendency to convert words of the u-declension into the o-declension and words of the e-declension into the ā-declension, e.g. B. senātus, -ī instead of senātus, -ūs ( but senati is already in Sallust), magistrātus, -ī instead of magistrātus, -ūs or māteria for māteria / māteriēs (= timber), effigia for effigiēs (= portrait).

- Change of gender, especially "decline" of the neuter (cf. Romance languages), e. B. cornus instead of cornū, maris instead of mare (= the sea), fātus instead of fātum, domus tuus instead of domus tua, timor māgna instead of timor māgnus.

- With a few exceptions (as in the Romance languages) every adjective can be increased by adding a prefix of plūs or magis , e.g. B. plūs / magis nobilis and sometimes together with the synthetic comparative plūs / magis nobilior. It is less common to use a comparative instead of a superlative, e.g. B. Venit sibi in mente, ut maiorem principem, qui in mundo esset, quæreret.

syntax

- In Middle Latin, the pronounalian (illa, illud) was also used as a definite article and the numeral ūnus (ūna, ūnum) was also used as an indefinite article.

- The demonstrative pronouns are usually no longer separated as sharply as in classical Latin. So hic, iste, ipse, īdem like is can be used.

- The two participles præfātus and prædictus (eigtl. Previously mentioned ) are often used as new demonstrative pronouns like illegal .

- Instead of the non-reflexive pronouns there are often the reflexive ones, i.e. sē = eum, suus = eius.

- Some verbs are combined with another case, e.g. B. adiuvāre, iubēre, sequī, vetāre + dat .; fruī, ūtī, fungī + Akk.

- Instead of an accusativus cum infinitivo , a quod or even a quia clause is often used (but already in the Vulgate ), quāliter clauses are also used in this function.

- The conjunction dum is often used instead of temporal cum .

- The narrative tense is no longer just the perfect tense and the present tense, but also the imperfect tense, even the past perfect tense. The present tense is also used instead of the future tense I and the perfect tense instead of the future tense II.

- The cōnsecutiō temporum (sequence of times) is no longer strictly observed. For example, subjunctive past perfect tense is often found in clauses instead of subjunctive past perfect tense.

- The final use of the infinitive, which is rarely and usually only poetically attested in classical Latin, is often used, e. B. Abiit mandūcāre for Abiit, ut ederet or mandūcātum abiit .

- Instead of the present active participle there is often a gerund in the ablative , e.g. B. loquendō for loquēns (cf. the Italian and Spanish gerundio and the French gérondif ).

vocabulary

The Latin of the Middle Ages is characterized by a considerably more extensive vocabulary, which is enriched on the one hand by new Latin formations with the help of prefixes and suffixes as well as semantic training , on the other hand it borrows from various other contemporary vernacular languages and Greek . Since a large part of the early Christian literature was written in this language and some Greek expressions had been retained in the Latin translation of the Bible, a considerable amount of Greek word material had already been incorporated into the Latin language in late antiquity. Even if the knowledge of the Greek language of most medieval scholars is not to be exaggerated, they were in a position to create further new formations based on Greek-Latin glossaries or bilinguals . Another source were the languages of the Germanic peoples who succeeded the Romans in Central Europe . In addition, many of the classic Latin words that were no longer in use were replaced by new words based on Vulgar Latin and the Germanic languages .

Examples

- Words that are too short are replaced by longer (and often more regular) words, e.g. B. īre by vadere, ferre by portāre, flēre by plōrāre, equus by caballus, ōs by bucca and rēs by causa;

- So-called Intensiva on -tāre often replace the underlying verb , e.g. B. adiutāre instead of adiuvāre, cantāre instead of canere and nātāre instead of nāre.

- Words taken over from antiquity often have new meanings: breve the letter, the document, convertere and convertī go to the monastery, corpus the host, plēbs the (Christian) community, homō the subordinate, comes the count ( cf.French comte , ital . conte ), dux the duke (cf. French duc ), nōbilis the free, advocātus the bailiff;

- Numerous new words are also created or borrowed: bannus (to English bann) the jurisdiction, lēgista the jurist, camis (i) a the shirt; see. the title De ente et essentia .

Middle Latin literature

Literary genres

The Middle Latin writers and poets strove to produce a literature whose focus was less on antiquity than on the present with all its profound social, cultural and political upheavals. The literary genres that have been cultivated are innumerable. Among the traditional genres (such as history , biography , letter , epic , didactic poem , poetry , satire and fable ) new ones, like the saint's legend , the translation report , the Miracle Collection , the visionary literature , the homily , the figure poem , the hymn and the sequence , the puzzle seal .

Of course, religious literature was of great importance. It encompasses both prose and poetic works and has partly a broader audience, partly the educated elite as a target audience. The popular versions of legends of saints (e.g. the Legenda aurea by Jacobus de Voragine ), miracle stories and other examples (e.g. the works of Caesarius von Heisterbach ) were aimed at a broad readership . In some cases, such works were translated into the vernacular at an early stage and also reached their audiences via sermons, for which they served as collections of material. Theological treatises, biblical commentaries and most of the poetic works had their place primarily in the school, sometimes also in court society and in the vicinity of educated bishops.

The ancient drama was initially not continued as it was tied to the requirements of ancient urban culture and was rejected by Christianity due to its connection with pagan cult. The dramas in Hrotswith von Gandersheim stand out as a contrast-imitative examination of the Terence model . Parody is widespread (only represented by a few examples in ancient times). New forms are spiritual play and comedia, which is completely independent of ancient drama .

Two fundamentally different techniques are available for poetry and are not infrequently used alternatively by the same author: the metric technique continued in the ancient tradition, which is based on the length of the syllables (quantity), and the technique derived from vernacular poetry, in which the number of syllables and the orderly sequence of stresses (accents) structure the verse. Metrical poetry is also stylistically in the tradition of the ancient poetic language, since mastering it requires intensive examination of classical models such as Virgil and Ovid as well as the Christian poets of late antiquity. Outsider phenomena here for some authors are the renunciation of the synaloeph and the use of rhyme, especially the so-called Leonine hexameter . The beginnings of the accenthythmic technique are closely related to the music of the Middle Ages , because almost without exception it is poetry set to music .

Prose and verse are used depending on the occasion and target audience, largely independent of the topic. Form types that combine prose and verse in different ways are opus geminum and prosimetrum . In prose, the accenthythmic clause, the cursus , prevails over the quantitating clause . Also encounters the rhyming prose .

meaning

The Medieval Latin literature is earlier than the vernacular literature and this also has a lasting effect: poets such. B. Dante Alighieri or Francesco Petrarca in Italy, some of whom still wrote in Latin, also transferred content and style to their works written in Italian.

In the light of what has been handed down today, the Germanic literatures appear to be even less independent and until the 12th century contain texts that were almost exclusively translated from Latin, more or less precisely. The Germanic folk and heroic poetry, which differed greatly from the ecclesiastical Mediterranean tradition, was initially no longer cultivated after the introduction of Christianity and was soon banned. Despite many indirect references to its former wealth, it was only saved for posterity in the rarest cases - by monks. In England alone, whose culture developed in the first centuries after the conversion quite free from patronage by continental currents (6th-9th centuries), a book literature in the vernacular emerged in the early Middle Ages, the oldest evidence of which is the all-round epic Beowulf . Similar legacies from the Franconian Empire mentioned by contemporary historians have been lost.

Conversely, of course, folk poetry also had a strong impact on Middle Latin literature. Since around the 12th century there have even been - e.g. B. in the Carmina Burana - numerous poems, which are partly written in Latin and partly in German.

Based on the ancient prerequisites (illustrations in specialist literature, poetry, the Bible), illustrated works have increasingly emerged since the Carolingian Renaissance , the illustration of which can be attributed to the author himself in individual cases. Literature production and book illumination are therefore closely related.

Medieval Latin literature does not take the place it deserves in science or in schools, because the many forms of language that were used as written language between late antiquity and humanism (approx. 550–1500) and their value are not sufficiently known. Until the very recent past, Middle Latin was viewed from a classical perspective as an inferior appendage to classical Roman literature. In some cases, the use of Latin in the Middle Ages is also misinterpreted as a regrettable suppression of the mother tongue and as a cultural alienation.

Middle Latin authors (selection)

| 6th century | 7th century | 8th century |

|---|---|---|

| 9th century | 10th century | 11th century |

|

||

| 12th Century | 13th Century | 14th Century |

See also

- Latin literature

- Category: Literature (Middle Latin)

- List of well-known Middle Latin philologists

- Classical Philology

- Neo-Latin Philology

Web links

- Glossarium ad scriptores mediæ et infimæ latinitatis (Ecole des chartes)

- Peter Stotz: The Latin Language in the Middle Ages ( Memento from April 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- Walter Berschin: Introduction to the Latin Philology of the Middle Ages

- Dag Norberg: Manuel pratique de latin médiéval (English)

literature

- Johann Jakob Bäbler : Contributions to a history of Latin grammar in the Middle Ages, Halle: Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses, 1885.

- Walter Berschin : Introduction to the Latin Philology of the Middle Ages (Middle Latin). A lecture. Edited by Tino Licht. Mattes, Heidelberg 2012, ISBN 978-3-86809-063-5 (general introduction).

- Bernhard Bischoff : Palaeography of Roman antiquity and the western Middle Ages. Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1979, ISBN 3-503-01282-6 ( Basics of German Studies 24), (Introductory work on the palaeography of the Latin Middle Ages).

-

Franz Brunhölzl : History of the Latin Literature of the Middle Ages. 3 volumes. Fink, Munich 1975-2009,

- Volume 1: From Cassiodorus to the end of the Carolingian renewal. 1975, ISBN 3-7705-1113-1 , online

- Volume 2: The Intermediate Period from the End of the Carolingian Age to the Middle of the Eleventh Century. 1992, ISBN 3-7705-2614-7 , online

- Volume 3: Diversity and Bloom. From the middle of the eleventh to the beginning of the thirteenth century. 2009, ISBN 978-3-7705-4779-1 .

- Ernst Robert Curtius : European literature and the Latin Middle Ages. 2nd revised edition. Francke, Bern 1954 (reference work on the history of literature).

- Monique Goullet, Michel Parisse : Textbook of Medieval Latin. For beginners. Translated from the French and edited by Helmut Schareika . Buske, Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-87548-514-1 (a textbook that does not require any knowledge of classical Latin).

- Gustav Gröber (ed.): Overview of the Latin literature from the middle of the VI. Century to the middle of the 14th century. New edition, Munich 1963.

- Udo Kindermann : Introduction to Latin Literature in Medieval Europe. Brepols, Turnhout 1998, ISBN 2-503-50701-8 .

- Paul Klopsch : Introduction to the Middle Latin verse theory. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1972, ISBN 3-534-05339-7 .

- Karl Langosch : Latin Middle Ages. Introduction to language and literature. 5th edition. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1988, ISBN 3-534-03019-2 ( The Latin Middle Ages ), (Introduction to the peculiarities of medieval Latin).

- Elias A. Lowe: Codices Latini Antiquiores. A Paleographical Guide To Latin Manuscripts Prior To The Ninth Century. 11 volumes. Oxford 1934–1966 (panels on palaeography).

- Max Manitius : History of Latin Literature in the Middle Ages. 3 volumes. Munich 1911–1931 ( Handbuch der Altertumswwissenschaft 9, 2), (reference work on the history of literature). Vol. 1 ( digitized version ), Vol. 2 ( digitized version ), Vol. 3 ( digitized version )

- Franz Steffens: Latin palaeography. 2nd, increased edition, Trier 1909 (125 tables with transcription, explanations and systematic presentation of the development of the Latin script), online .

- Peter Stotz : Handbook on the Latin language of the Middle Ages . 5 volumes. CH Beck, Munich 1996-2004 ( Handbook of Classical Studies 2, 5), (including a history of language and grammar).

- Ludwig Traube : Lectures and Treatises. Volume 2: Introduction to the Latin Philology of the Middle Ages. Published by Paul Lehmann . Beck, Munich 1911 (introduction to Middle Latin philology by one of the founders of the university subject Middle Latin).

Dictionaries

A comprehensive, complete modern dictionary of the Middle Latin language does not yet exist. The basis of the lexical work are first of all the dictionaries of classical Latin such as the Thesaurus linguae latinae (volumes IX 2, fasc.1-14, bis protego have been published so far ), Karl Ernst Georges' extensive Latin-German concise dictionary and the Oxford Latin Dictionary . For words or meanings used exclusively in Middle Latin, the following should also be used:

- Old comprehensive and manual dictionaries

- Charles du Fresne, sieur du Cange u. a .: Glossarium ad scriptores mediae et infimae latinitatis (monolingual), first 1678 ( Glossarium ad scriptores mediæ et infimæ latinitatis , Niort: L. Favre, 1883–1887, École nationale des chartes ).

- Egidio Forcellini : Totius latinitatis lexicon , first 1718 (also edited by Vincentius De-Vit, Prati 1858–1875); 2 vols. Onomasticon , Padova 1940.

- Lorenz Diefenbach : Glossarium latino-germanicum mediae et infimae aetatis , Joseph Baer, Frankfurt am Main 1857; Reprint Darmstadt 1968 ( facsimiles at Google Books ).

- Lorenz Diefenbach : Novum glossarium latino-germanicum mediae et infimae aetatis , Sauerländer, Frankfurt am Main 1867 ( facsimiles at archive.org ); Reprint Aalen 1964.

- Modern manual dictionaries

- Albert Blaise : Lexicon latinitatis Medii Aevi , praesertim ad res ecclesiasticas investigendas pertinens, CC Cont.med., Turnhout 1975.

- Albert Blaise: Dictionnaire latin-français des auteurs chrétiens , Turnhout 1954.

- Albert Sleumer: Church Latin Dictionary , Limburg / Lahn: Steffen 1926; Reprinted by Olms, Hildesheim 2006.

- Edwin Habel: Middle Latin Glossary. With an introduction by Heinz-Dieter Heimann. Edited by Friedrich Gröbel, 2nd edition Paderborn / Munich / Vienna / Zurich 1959; Reprint (with new introduction) 1989 (= Uni-Taschenbücher , 1551).

- Friedrich A. Heinichen: Latin-German on the classical and selected medieval authors. Stuttgart 1978 (several reprints, e.g. as Pons global dictionary).

- Younger, more comprehensive dictionaries

- Otto Prinz , Johannes Schneider a. a. (Ed.): Middle Latin dictionary up to the late 13th century . Beck, Munich 1954ff. (In development, should cover the use of the word up to the end of the 13th century).

- Franz Blatt (Ed.): Novum Glossarium mediae latinitatis ab anno DCCC usque ad annum MCC , Copenhagen 1957ff. (under development, starts with "L").

- Jan Frederik Niermeyer : Mediae latinitatis lexicon minus ( Lexique latin médiéval - Medieval Latin Dictionary - Middle Latin Dictionary ). Edited by Co van de Kieft, Leiden [1954-] 1976, reprinted ibid. 2002 (only a few sources cited).

- More specialized dictionaries and word lists

- JW Fuchs, Olga Weijers (Ggg.): Lexicon latinitatis Nederlandicae Medii Aevi , Leiden 1977ff. (in development, previously A to Stu).

- R [onald] E [dward] Latham: Revised medieval Latin wordlist from British and Irish sources. , London 1965; Reprints there in 1965, 1973 and more.

- RE Latham: Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources , London 1975ff.

- Lexicon mediae et infimae latinitatis Polonorum , Warsaw 1953ff. (in development, previously A to Q).

- Latinitatis Medii Aevi lexicon Bohemorum , Prague 1977ff.

Magazines

- Middle Latin yearbook . Founded by Karl Langosch, currently edited by Carmen Cardelle (et al.), Stuttgart 1964ff.

- The Journal of Medieval Latin. Published on behalf of the North American Association of Medieval Latin, Turnhout 1991ff.

Individual evidence

- ↑ For example: Rupprecht Rohr : The fate of the stressed Latin vowels in the Provincia Lugdunensis Tertia , the later ecclesiastical province of Tours . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1963.

- ↑ See Peter Stotz: Handbook on the Latin Language of the Middle Ages , Vol. 3: Phonology. CH Beck, Munich 1996 (see literature).

- ↑ JF Niermeyer, Mediae Latinitatis Lexicon Minus , p. 509 (right column) and 1051 (left column)

- ^ Cf. Karl Polheim : Die Latinische Reimprosa , Berlin 1925

- ↑ Henrike Lähnemann: Rhyming prose and mixed language with Williram von Ebersberg. With an annotated edition and translation of his 'Aurelius Vita'. In: German texts from the Salier period - new beginnings and continuities in the 11th century , ed. by Stephan Müller and Jens Schneider, Munich 2010 (Medieval Studies 20), pp. 205–237 ( Open Acces Preprint ).