Richard Meinertzhagen

Richard Meinertzhagen , DSO , CBE (born March 3, 1878 in Kensington , London , † June 17, 1967 there ) was a British officer and naturalist . He was particularly active in military reconnaissance and most recently held the rank of colonel . In addition, he owned the largest private collection of bird preparations in his day and wrote several standard works on ornithology . His biographer Brian Garfield later accused him that his bird collection was partially stolen or manipulated with regard to the origin. He also accused him of numerous exaggerations and false assertions regarding the military and secret service adventures in his diaries. These had previously been widely accepted in historical studies and were long considered a trustworthy source. Meinertzhagen was also one of the role models for Ian Fleming's fictional character James Bond .

Origin and youth

Meinertzhagen was born into a banking family that belonged to the British financial aristocracy. This English branch of the family went back to the Bremen banker Daniel Meinertzhagen V. (1801–1869), who came to England in 1826 and was naturalized in 1837. He married the daughter of the banker Frederick Huth and from 1850 became a partner in the bank Frederick Huth & Co., which became the second most important Anglo-German commercial bank after the Rothschilds . Richard's father Daniel VI. (1842–1910) was a senior partner of the bank, his mother Georgina (–1914) a née Potter. Richard was the third of ten children and the second son. His parents' marriage appears to have been unhappy, and most of them lived separately. The children were raised by a nanny.

When Meinertzhagen was seven years old, the family moved to the former monastery of Mottisfont , Romsey , in the Test Valley of Hampshire , which they had acquired. This included an estate of 800 hectares, which was tended by a large servants. Meinertzhagen learned to hunt here and became an avid bird watcher. According to his own statements, he claims to have gone on long hikes with Herbert Spencer , and Charles Darwin still kept him on his knees (a pipe supposedly belonging to Darwin, which Meinertzhagen donated to the Linnean Society in 1958 , turned out to be produced in Birmingham in 1928). In fact, he was known to the suffragette Beatrice Webb because it was his aunt.

Meinertzhagen first attended a boarding school in Aysgarth in the north of England, then in Fonthill . He later followed his big brother to Harrow to the same school that Winston Churchill graduated from a few classes above him. He must have been an excellent student, because within four years he mastered the material of six school years and was also a good athlete. In 1895 he joined his father's bank and was sent to Cologne and Bremen the following year - he was 18 years old. Here he learned fluent German, but the banking business bored him. After nine months he returned to England.

He was able to persuade his father to allow him to join the Hampshire Landwehr Cavalry ( Hampshire Yeomanry ). His older brother Dan was planned to continue the family bank, but died in 1898 of appendicitis while in Germany. Meinertzhagen suddenly found himself in the role of the eldest son at the age of 19. His father tried to arouse interest in the banking business by giving it to a stockbroker friend for training, but Meinertzhagen was all too obviously unsuitable for this. He began an officer course in Aldershot and joined the Royal Fusiliers Regiment in 1899 as a lieutenant .

Military career

Beginnings in India

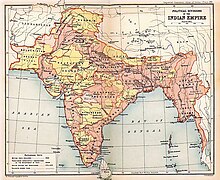

Meinertzhagen left England in February 1899 to join a battalion of his regiment stationed in India - the start of a 25-year military career. According to his diaries, he already experienced a number of adventures at the beginning of the journey. He claims to have rescued a little English girl from a brothel during a stay in Cairo or to have dispersed the daily parade of troops with a continuous elephant. No evidence can be found for stories like this outside of Meinertzhagen's books, but they were well told and later earned him a loyal readership. In fact, he fell ill with typhus and was sent to England and various places in British India to recover . In Wellington in the Nilgiri Mountains of South India, he befriended the young FM Bailey , who later became known as a spy . He last served in a unit of mounted infantry in Mandalay in 1901/02 , but, according to his claims, never held a command.

The Nandi massacre

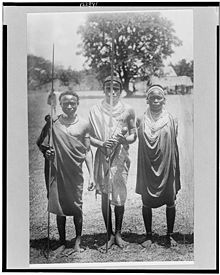

In 1902 Meinertzhagen was transferred to the King's African Rifles in British East Africa . After a brief stay in Nairobi , he took up service at the Fort Hall outpost in the Kikuyu settlement area . Meinertzhagen later claimed to have commanded Fort Hall as well, in fact he was third or fourth in the ranking. If one follows his diary, which has been published as the Kenya Diary , then, according to his biographer Brian Garfield, he is guilty of genocide . Meinertzhagen repeatedly describes scenes in which he and his soldiers wiped out the inhabitants of entire villages and did not spare the children either. Taken together, he claims to have killed around 1,500 people. These bloodthirsty fantasies are still often cited as a prime example of British imperialism . In fact, with one exception , there is no evidence in the carefully kept files of the British Army , in which much smaller incidents were meticulously noted, that Meinertzhagen's self-accusations could be true. Rather, he was used for mapping and was dedicated to hunting. On this occasion he discovered the giant forest pig Hylochoerus meinertzhageni in 1904 , which is named after him. He sent not only animal skins but also a large number of insects and pressed plants to England.

The only massacre for which Meinertzhagen was actually responsible caused an international scandal (see Nandi Expedition ). In 1905 he was employed as an adjutant in the Nandi Fort in the highlands of Kenya (he calls himself the commander again). Members of the Nandi felt disturbed by the construction of the railroad to Uganda and tried to sabotage it. According to the files, the commander of the British units in the area, Lt. Col. Edgar G. Harrison, and his adjutant, Major Ladislaus Herbert Richard Pope-Hennessy, therefore proposed that the Nandi warriors be set up on Ket Parak Hill. When events did not develop as planned, they were glad when Meinertzhagen voluntarily took over the entire responsibility. As far as the conflicting reports suggest, the Nandi leader, the so-called Laibon, was invited to peace talks. When he appeared with around 25 warriors, Meinertzhagen massacred the peace delegation together with another five soldiers. The opposition to British rule was ended in one fell swoop. According to Meinertzhagen, he fought with a pistol and the other side with spears. Meinertzhagen's biographer Brian Garfield has reconstructed a sequence in which the Nandi warriors were shot with a Maxim machine gun .

Between late 1905 and early 1906, the Nandi massacre was investigated three times by commissions, each of which declared Meinertzhagen's conduct to be honorable. However, the colonial department of the British Foreign Office insisted that Meinertzhagen - meanwhile promoted to captain - should be withdrawn from Africa and ordered back to England. He used the connections of his influential family there and finally succeeded in being sent to the 3rd Battalion of his regiment, the Royal Fusiliers , in Cape Town in February 1907 .

According to Meinertzhagen - who found no support anywhere outside of his diaries - he was used as a spy in 1910 to spy out a Russian fort in the Crimea . He has many adventures, the wildest on a train ride through the Greek mountains, during which the train derails. A wagon hangs over the abyss and Meinertzhagen hears a young woman scream. He saves her just before the car falls into the abyss. Such fantasies were later taken to be facts by Meinertzhagen biographers, but no corresponding railway accident in Greece can be proven for 1910. In real life Meinertzhagen was stationed in Mauritius from July 1910 (again he falsely claims to have been in command), where he wrote his first ornithological article. He applied for the staff officer course in Sandhurst , was rejected, but accepted at the Staff College in Quetta , which is why he traveled to India again in 1911. In 1913, his right eye was hit by a pellet in a gun accident. He spent several months in the hospital, almost lost his eye, and has been wearing glasses ever since.

An incident is said to have happened in May 1913, for which there is also only his diary as a source. Meinertzhagen therefore visited his polo ponies in their stable and discovered that they had been mistreated by the servant. In his anger, he killed the servant with a polo stick. This story, too, was later quoted as evidence of the character of British imperialism. In any case, Meinertzhagen found nothing in portraying himself in public as a mass murderer and manslayer .

Chief of the military reconnaissance in the campaign against Lettow-Vorbeck in East Africa

When the First World War broke out , the so-called Force B was sent from India to East Africa under General Arthur Aitken . Meinertzhagen describes himself in his diaries - in which many historians have followed him - as their chief of military reconnaissance (in fact, this task was initially carried out by Lieutenant Colonel JD Mackay). The first mission was a failed landing in front of Tanga , where Meinertzhagen claims to have participated in the fighting. There is no evidence of this outside of his own writings. In fact, on November 5, 1914, after almost all of the landing troops had withdrawn to the ships after the loss of 1,500 men and almost all weapons, he was sent to the shore because of his knowledge of German to negotiate the armistice and exchange the wounded prisoners. The catastrophic defeat was kept secret on the British side for months.

In 1915 Meinertzhagen - promoted to major - actually became chief of the military reconnaissance of the British East Africa Corps. According to his own statements, he built a spy ring in East Africa until 1916, for which he mainly recruited black Africans who could cross the front line without attracting attention (in fact, the spy ring was built by Mackay, which then failed due to malaria and was replaced by Meinertzhagen). They are said to have successfully spied on Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck's plans . This contradicts the fact that the commander of the German protection forces managed for years to evade the British persecutors and repeatedly attack them in unexpected places. Occasionally it was even suspected that the position of British troops had been betrayed to the Germans.

According to the diary, Meinertzhagen claims to have seen through Lettow-Vorbeck's tactics as early as November 1914: “Von Lettow will not face the fight. He will whiz around and keep as many of us busy as possible. ”According to the documents that have come down to us in the army files and from other witnesses, there is nothing to suggest that Meinertzhagen understood the enemy during the war. His biographer Brian Garfield attributes the factual failure of his educational work to the fact that most of the agents belonged to the Nandi tribe. They had been assigned to the British officer of all people who had massacred their Führer ten years earlier, and so they had every reason to work for the Germans.

Meinertzhagen also prides itself on having forged the money used in German East Africa in large quantities and thus successfully destabilizing the currency. In fact, under his guidance, the German 20 rupee banknote was forged. However, the paper was stiffer than the original and all notes had the same serial number so that the forgeries were easy to spot. However, today they have a high collector's value among numismatists , so that there could hardly have been "several million" of them, as Meinertzhagen claims. Meinertzhagen again reports on adventures he claims to have experienced during commando operations, while his own files show that he was sitting at his desk in Nairobi. In November 1916 he was sent back to England because of his poor health. After the war he visited von Lettow-Vorbeck in Germany, and the two stayed in contact for decades.

The conquest of Beersheba

At the end of May 1917, Meinertzhagen reported to his new office in Cairo. According to his own statements, Meinertzhagen claims to have led dozens of agents behind the Turkish lines. In fact, the success of the British Enlightenment during this period can be traced back to the fact that British cryptanalysts in Room 40 succeeded in deciphering the codes of the German and Turkish radio messages. Meinertzhagen claims that he had the idea of installing a receiving station on top of the Great Pyramid of Cheops , but this and other receiving stations already existed a year before he came to the Middle East. On November 21, 1917, the largest airship ever built, the L 59 , took off from Bulgaria to deliver supplies to the German protection forces in East Africa. Meinertzhagen prides himself on having sent the captain a forged radio telegram, according to which Lettow-Vorbeck had surrendered and the zeppelin was supposed to turn back. In fact, the order to turn back was given on November 23 by the major German radio station in Nauen .

In the English-speaking world, Meinertzhagen's name is mainly associated with the so-called haversack ruse (German: "List with the provisions bag"). This deception actually took place, except that Meinertzhagen was not involved. During the First World War, a British expeditionary force under Edmund Allenby planned the invasion of Palestine . It came from the Sinai desert and the route to Palestine was blocked by the fort in Gaza held by Ottoman troops with German military advisers . To the east of it stretched the Negev desert , and the only way to catch water was in the Be'er Sheva oasis , which was also defended by three divisions . Allenby could actually only operate within the area served by the Sinai Railway via Suez .

In order to deceive the Ottoman commanders, the haversack ruse was staged in September 1917 . A British officer "lost" within sight of a Turkish patrol a haversack, a 20- pound - grade at the time a lot of money - - contained a letter from his wife that heralded the birth of the Son, and the military plans of Allenby. According to this, the British had postponed the attack, whose thrust would be directed against Gaza, until the end of the year. Only a diversionary attack would be launched against Beersheba. Thereupon the Australian general Harry Chauvel moved his cavalry troops at night before Be'er Scheva and captured the place in a surprise attack. With Beersheba in British hands, the expeditionary force's water supply was secured and Allenby was able to conquer Jerusalem before Christmas .

The German commander, General Kress von Kressenstein , states in his memoirs that he was not deceived by the haversack ruse because it was not possible to postpone the attacks into the rainy season. On the German and Ottoman sides, an attack on Beersheba was considered hopeless for logistical reasons.

Meinertzhagen added to the story that he had survived a plane crash four days before the haversack ruse . He himself was head of the military reconnaissance under Allenby, and in his book Army Diary he cites numerous documents that allegedly prove that he himself carried out the haversack ruse . In reality Meinertzhagen held a subordinate position in the rank of major, but not in Allenby's staff, but at MI-7 , responsible for censorship and propaganda . Meinertzhagen's main job was the production of cards, which he was indeed excellent at.

The story of the haversack ruse with Meinertzhagen as the main character has gone down in numerous history books and shown in the film The Lighthorsemen . In fact, the haversack ruse was invented by Lieutenant Colonel James D. Belgrave . He could no longer defend himself against the later appropriation by Meinertzhagen because he fell on June 13, 1918. The haversack ruse was carried out by Arthur Neate , who also confronted Meinertzhagen by letter in 1927. Neate refrained from going public, presumably because he was now working within the diplomatic service for military intelligence and therefore did not want to cause a stir. Neate publicly corrected the story in a letter to the editor in 1956. Meinertzhagen excused himself by saying that the haversack ruse had apparently been tried several times.

The alleged game of cat and mouse with the German spy master Fritz Frank

Rumors circulated among British soldiers in the Middle East that a German master spy named Fritz Frank was responsible for various accidents. According to Meinertzhagen, while questioning prisoners of war, he came across a Greek employee Frank, whom he persuaded to work for the British. This double agent arranged for him to meet the German spy on a dark night in a wadi . There was an exchange of fire that killed a young woman. Months later, during a house search in Jaffa, he came across photographs, the sight of which made it clear to him that the "Greek" was Frank and that he had accidentally shot his wife. After the war, Meinertzhagen claims to have met Frank again on an assignment in Germany. The alleged cat-and-mouse game with the German master spy Fritz Frank is also one of the popular myths surrounding Meinertzhagen and has been included by various authors in books on British secret service work.

The alleged attempt to rescue the tsarist family

At the end of 1917 Meinertzhagen was ordered back to England. In the summer of 1918 he was sent to the Allied headquarters in France and promoted to colonel on a temporary basis . He continued to spend longer stays in England. During this time, at the personal request of King George V, he claims to have been involved in a commando operation to free the family of Tsar Nicholas II who were held captive in Yekaterinburg . The mere fact that he claims to have carried out this rescue operation with a Havilland DH-4 biplane, which in addition to the pilot only offered space for one other person, shows that Meinertzhagen's information cannot be trusted. The allegedly attempted liberation of the tsarist family was later processed into a book.

On November 11, 1918, Meinertzhagen claims to have been the officer who was supposed to deliver the German declaration of surrender in the First World War to Field Marshal Douglas Haig . His car exploded on the way. Seriously wounded, he found a ride on a truck and delivered the historical document to Haig. There are no documents that could prove or disprove Meinertzhagen's story. In fact, he was treated for an abdominal injury in the weeks that followed.

Commitment to Zionism

Until 1917, Meinertzhagen described himself as a common anti-Semite with no particular interest in Judaism . He attributes his change to a Zionist - a supporter of a Jewish state in Palestine - to his meeting with Chaim Weizmann and Aaron Aaronsohn . Aaronsohn ran a spy ring ( NILI ) in Ottoman-ruled Palestine , which collected information for the British army .

In the spring of 1919 Meinertzhagen took part in the peace conference in Paris . For this purpose he was temporarily attached to the staff of Foreign Minister Balfour . At the conference the Arab interests were represented by the famous TE Lawrence ("Lawrence of Arabia"), the Zionist interests by Meinertzhagen (both had known each other from their secret service work since 1917). During the First World War, the British government had made extensive promises to the Arab and Zionist sides ( Balfour Declaration ) which it now refused to keep. They are at the root of today's Middle East conflict .

In the autumn of 1919 Meinertzhagen was appointed Political Officer for Palestine, an office in which he was supposed to mediate between the British military government under Allenby and civilian authorities. The Zionist Bureau under Chaim Weizmann had used its influence to get Meinertzhagen to receive this post. The period up to 1922 was the climax of his actual influence. In April 1920, during Passover , the bloody Nabi Musa riots broke out in Jerusalem. On this occasion, the Zionist leader Vladimir Jabotinsky was sentenced to 15 years in prison, which was lifted on Meinertzhagen's intervention. Meinertzhagen complained to Allenby about the anti-Semitic attitude of numerous British officers and accused them of having provoked the "bloody Passover". In April 1920 he bypassed official channels and complained directly to Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon . Allenby released him immediately.

When Churchill became Colonial Minister in 1921, he requested Meinertzhagen for the Middle East Department. The League of Nations mandate for Palestine was formally not under Churchill's jurisdiction, but the creation of a Middle East department was one of the power struggles with which Churchill expanded his influence. His desk was next to TE Lawrence's. A friendship with Harry St. John Bridger Philby - British advisor to the later founder of Saudi Arabia Ibn Saud and bird lover like Meinertzhagen - who was actually considered a violent anti-Semite, also dates from this time . Meinertzhagen worked as a kind of liaison officer for the War Ministry in the Colonial Ministry and was responsible for the budget and logistics of the military government of Palestine. Churchill confronted him in June 1922 because information from the Colonial Office had apparently been passed on to the Zionist Office in London. Meinertzhagen denied that it was the leak, but as a result he was only occupied with subordinate activities. In the autumn of 1922 he made a month-long inspection tour of the Middle East, and in 1923 another long journey to the Middle East, North Africa and India. In the military he was assigned to a new regiment , the light infantry of the Duke of Cornwall . In 1925 he submitted his departure and his pension was reduced to that of a major.

In the 1930s Meinertzhagen became a member of the Anglo-German Association . British business people who felt hindered by the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles and wanted to expand their business with the German Reich had organized themselves in it. In this context, Meinertzhagen met with Joachim von Ribbentrop for dinner in 1934. At the same time he was a member of Focus , a discreet lobby group around MP Winston Churchill that worked against National Socialism . Meinertzhagen made several trips to Germany. According to his own account, he claims to have met Adolf Hitler three times , and at the last meeting on June 28, 1939 in Berlin, he claims to have had a loaded pistol in his pocket. In his diary he reproaches himself for missing the opportunity to shoot Hitler and Ribbentrop at the same time. There is no independent source for any of these meetings, although the British Embassy in Berlin closely monitored all British visitors to the German government. Hitler actually spent the last-mentioned appointment in Berchtesgaden .

Meinertzhagen remained committed to Zionism for the rest of his life, even though occasional anti-Semitic attacks have been passed down from him. In 1948, during a visit to the newly founded Israel - Meinertzhagen was now 70 years old and suffered from arthritis - he and Hagana relatives fought against Arab snipers on Haifa beach . In 1953 he visited Israel again and was received like a head of state.

The death of his second wife

Meinertzhagen had married Armorel Le Roy-Lewis in 1911. The marriage turned out to be disastrous. For the divorce after just over a year, Meinertzhagen was seen at a meeting with a prostitute - at that time a frequently used means to legally dissolve a marriage under British law. In 1921 he married Annie Constance Jackson, who was an eminent ornithologist. This marriage resulted in two sons and a daughter. The eldest son later died in World War II , and Richard Meinertzhagen memorialized him in 1947 with the book The Life of a Boy .

Annie Meinertzhagen was the heir to an extensive fortune and two estates. The Meinertzhagen bank, which was run by Richard's younger brother Louis, had gotten into trouble, so that Richard Meinertzhagen lived mainly on his wife's fortune. During his early retirement, he undertook extensive trips, often accompanied by Annie, the longest of which in 1925/26 to India in the region between the Himalayas, Burma and southern India. He collected mammals, butterflies, flies and other insects, plants and above all birds, which he prepared himself. In 1927/28 he published an important work on Asian birds, in which he claimed to have collected important specimen copies himself. As a direct participant in the expedition, Annie Meinertzhagen must have known that her husband was lying. Another possible motive, according to his biographer Brian Garfield, was that he showed an increasing interest in his 33-year-old cousin Theresa Clay. In any case, Annie Meinertzhagen changed her will in 1927 in such a way that in the event of her death, her property would no longer go to her husband, but should be administered by an executor for the children. As long as he did not remarry, he should only receive a fixed pension. Meinertzhagen made a long trip to Egypt in 1927/28, while Annie gave birth with the third child in his absence.

Annie Meinertzhagen died on July 6, 1928 as a result of a gunshot wound. In the portrayal of Meinertzhagen, the couple had undertaken target practice. When he went to the target, he heard a shot, turned around and saw his wife lying dead on the ground. She shot herself while checking to see if her revolver was empty. However, the firing channel ran diagonally from the top front to the back and bottom, and Meinertzhagen was about a foot taller than his wife Annie. She had been proficient with firearms since childhood and had shot numerous birds herself. Since Meinertzhagen was the only witness to the incident, the death was declared an accident by the police. In the following weeks, according to his diaries, Meinertzhagen sank into depression , and on September 11, 1928, he volunteered to be admitted to a psychiatric institution , where he stayed for a year.

Meinertzhagen made sure that his cousin Theresa Clay received a good scientific education, which she completed with a doctorate at the University of Edinburgh . She became a world-renowned expert on bird lice from the Mallophaga group . Meinertzhagen named a dozen bird species he discovered after her, such as the Afghan sparrow Montifringilla theresae . For more than thirty years they traveled together, wrote scientific papers together, and towards the end of his life she looked after him. She and her sister Janet also raised his children. Meinertzhagen usually introduced her as his housekeeper, she in turn referred to him as "Uncle Dick". The 1930s were filled with trips to Estonia, Russia, Germany, Kenya, Uganda, Sudan, Egypt, India, Afghanistan, Finland, Morocco and the United States.

At the beginning of the Second World War, Meinertzhagen was reactivated with the rank of lieutenant colonel for military reconnaissance. Again, his diaries are filled with supposedly fantastic deeds. In fact, Meinertzhagen was busy placing propaganda articles in the British press and censoring unpleasant reports. In the spring of 1940 he was finally given retirement. According to his own account, however, he was involved in Operation Dynamo , during which British troops were evacuated from Dunkirk .

Work on your own fame

A quote from former British Prime Minister David Lloyd George shows what reputation Meinertzhagen enjoyed . With a view to the famous Haversack Ruse, he wrote in his memories of the war: “[Meinertzhagen] seemed to me to be one of the most capable and successful people I have ever met in an army. That was enough to make him suspicious and prevent his ascent to the highest ranks of his profession. "

Meinertzhagen's diaries are covered with allusions that he was a spy licensed to kill (“my other work”). In 1930, for example, he allegedly caught and shot a group of Bolshevik agents on a farm near Ronda in Spain. In fact, he was out on a bird hunt at the time. His diaries consist of a loose-leaf collection in 70 volumes. The way in which the texts are typed and the quality of the paper can differ from page to page, so that it appears as if Meinertzhagen has subsequently exchanged individual pages. He claims to have bought the typewriter he used throughout his life in 1906. The special type - a Garamond pica cursive script - was only available in the commercial trade since 1920, so that Meinertzhagen seems to have written at least the diaries up to 1920, including his haversack ruse (according to his own statements, he only got the volumes up to 1907 from his handwritten diary up to then typed).

In the 1930s Meinertzhagen made the acquaintance of Ian Fleming , who was a generation younger and who was then working as a financial correspondent for the Reuters news agency . Both were members of Winston Churchill's Focus group. They became friends, and Fleming's future fictional character James Bond has many of Meinertzhagen's traits.

Ornithology

Meinertzhagen got to know Walter Rothschild , the leading British bird expert and founder of the Bird Museum in Tring , now part of the Natural History Museum , as a student at Harrow . Bird watching was an important hobby of the British upper class at the time, and Meinertzhagen was thus able to establish important contacts with Edmund Allenby, for example. He was well known to Erwin Stresemann among the German ornithologists . He also became a close friend of leading Indian ornithologist Sálim Ali , chairman of the Bombay Natural History Society , who did not seem to hold against him for his frequent racist remarks.

Meinertzhagen published over a hundred articles and twelve books on ornithology, among which Birds of Arabia stands out, which is based on the unpublished book Birds of Arabia by George Latimer Bates . Typical of him is a style rich in anecdotes and a humanizing description of birds, which earned him recognition and rejection alike. The prime example of this is his behavioral book Pirates and Predators . The predator here is a bird of prey that flies away with its prey. The pirate swoops away from him. His scientific work dealt mainly with the bird fauna of the Palearctic region, North Africa , the Middle East and the Himalayan region; In addition, there are also publications on Mauritius , East Africa , South West Africa and Greenland . He also completed the book Nicoll's Birds of Egypt by his friend Michael Nicoll, who had died in 1925.

In addition, Meinertzhagen and his cousin Theresa Clay were the leading specialists in bird lice ( Mallophaga ). Their collection comprised 600,000 copies, the largest in the world at the time. Meinertzhagen donated it to the Natural History Museum in 1951 . In 1957, ten years before his death, Meinertzhagen also donated his entire collection of over 20,000 birds to the Natural History Museum , which Ernst Mayr described as the largest and most beautiful private collection in the world. He was then made an Honorary Associate of the museum and even received a key to the museum.

Meinertzhagen was Vice President of the British Ornithologists' Union from 1940 to 1943 ; for his services he was awarded the Godman Salvin Medal in 1951. The American Ornithologists' Union made him an honorary member. In 1957 he was awarded the CBE by the Queen for his services to ornithology .

Commitment to a bird sanctuary on Heligoland

Meinertzhagen fought for decades to preserve Heligoland as a bird sanctuary . During the peace negotiations in Paris in 1919, he campaigned for the island to be designated a bird sanctuary. After the Second World War he took up this concern again. He organized a petition, and after long disputes with the British Foreign Office , Heligoland was given the status of a bird sanctuary again in 1951.

The Meinertzhagen scandal

On four different occasions, employees of the British Museum (Natural History) reported to their superiors that after Meinertzhagen visits, bird hides were missing from the collection. The fourth time, the overseer of the ornithological department, CF Regan, hired him. In his briefcase he found nine bird hides, which Meinertzhagen claimed he wanted to borrow to work on at home. Meinertzhagen was then banned from visiting the bird department in 1919. It was lifted after a year and a half under pressure from Lord Walter Rothschild.

Individual ornithologists were also skeptical of Meinertzhagen and expressed this to specialist colleagues. FE Warr wrote in a letter to Charles Vaurie : “I am ready to swear that the Meinertzhagen collection contains bellows that have been stolen from the Leningrad Museum, the Paris Museum and the American Museum of Natural History . […] He also removed labels and replaced them with others that matched his ideas and theories. ” Phillip Clancey , who had traveled with Meinertzhagen and collected with him, pointed out that many of Meinertzhagen's labels had questionable locations or data were provided.

In the early 1990s, the ornithologist Alan G. Knox then examined all the siskins from the Meinertzhagen collection ( Carduelis flammea and C. hornemanni ). The bird hides, insofar as they were collected and prepared by Meinertzhagen himself according to the label, fell into two groups. One group was prepared in a uniform style that probably corresponds to that of Meinertzhagen. The other group, to which the technically superbly groomed birds and birds with impeccable plumage belonged, had been groomed in different styles. The preparation style is so characteristic of the respective taxidermist that Knox was able to assign some of the birds to certain other taxidermists. Some of these birds were even reported missing in the Natural History Museum , so that Meinertzhagen later donated birds that he had stolen from this museum as part of his own collection. According to Knox, the motive for some of the forgeries was to establish Carduelis flammea britannica as an independent subspecies. In general, Meinertzhagen acquired particularly beautiful birds.

Alan Knox published his warning in 1993 in the journal Ibis . As a result, three subspecies had to be deleted from the list of bird species occurring on the British Isles, for which Meinertzhagen had supplied either the only or the first evidence ( Falco columbarius columbarius , Gallinago gallinago delicata and Eremophila alpestris alpestris ).

Case study for a forgery: The Blewitt-Kauz

In 1999, the ornithologists Pamela C. Rasmussen (then at the Smithsonian Institution , now Michigan State University ) and Nigel J. Collar from BirdLife International, using the Blewitt owl as an example, demonstrated that the distribution map of a bird species also had to be redrawn outside the British Isles. At the time, seven bellows of this owl were known in collections. Four of the specimens had been collected by the British colonial official James Davidson, and another from the British Museum was considered missing. One copy came from Meinertzhagen. According to the label, he had it on October 9, 1914 - that would be 30 years later than the rest of the birds - and at a different location - near Mandvi in the Tapti Valley in the Surat- Dangs area of Gujarat in the western foothills of the Satpura Mountains - collected. The owl hadn't been seen since then.

Rasmussen and Collar compared Meinertzhagen's specimen with a series of owls that Meinertzhagen had in all likelihood actually shot and groomed himself in 1914, as well as with the other known Blewitt owls and other birds that undoubtedly came from Davidson. In the Meinertzhagen copy, almost all of the stitch holes were cut away from the original seam; this cut must have been made when the bird was completely dry. The bird was then stuffed anew and loosely sewn up again. Body fat usually leaks out of old bird hides and stains feathers, feet and beak. This specimen, on the other hand, had been freed from fat with a solvent and there were remains of a white powder that had apparently been used for drying. If this treatment had been carried out immediately after the bird's death, oily remains in the plumage, on the feet or on the beak would have been expected. The feet were subsequently twisted.

In the Meinertzhagen copy there was still some of the original cotton wool used for darning near the ells . When analyzed in the FBI's trace lab, it was found to be the same cotton as the Davidson specimens. Davidson was probably self-taught in the preparation of birds and used a very peculiar style, including tying the wings from the outside . Remains of the cord used in this process could also be found on the Meinertzhagen copy.

Meinertzhagen's diary, too, if taken seriously as a source, makes it seem unlikely that he could have collected the Blewitt-Kauz. According to the diary, he was in Bombay on October 6th and 13th. Accordingly, the officer Meinertzhagen would have made an elaborate trip to the inaccessible valley of the Tapti at a highly inopportune time - the First World War had broken out for two months and the British army had also been mobilized in India - and stayed there for a day or two at most Shot an extremely rare bird on this occasion - the only specimen in the 20th century - without recording this exciting event in his diary or publishing it later. Also in Meinertzhagens’s register of the shot birds there is no reference to the event or even entries about other birds collected in the area.

The Meinertzhagen specimen of the Blewitt owl was introduced into the specialist literature in 1969 by his friend, the respected Indian ornithologist Sálim Ali , only two years after Meinertzhagen's death (nothing indicates that Ali knew of Meinertzhagen's forgeries or was involved in them) . Rasmussen and Collar came to the conclusion that the specimen allegedly shot by Meinertzhagen must actually be the specimen from the British Museum that Davidson collected and is now missing . Meinertzhagen had re-prepared the owl to cover up the theft and given a new location and date. The forgery later led Ali to search Mandvi for the Blewitt owl, where he probably never lived. Numerous other birds from the Meinertzhagen collection show signs of new preparation, as described here using the Blewitt owl as an example.

Together with Robert Prys-Jones , the head of the bird department of the Natural History Museum in London, Pamela Rasmussen was finally able to show that fourteen records of bird species or subspecies on the Indian subcontinent, for which Meinertzhagen had provided the only evidence, were falsified. In many cases the information was incorporated into the ornithological literature. In 2005 the journal Nature published an article informing the broad scientific public about the gigantic extent of Meinertzhagen's forgeries. Pamela Rasmussen was quoted here as saying that there are hundreds, probably thousands, of wrongly cataloged bird skins in the collections through Meinertzhagen. The correction of the damage caused by Meinertzhagen came for South Asia the following year with the publication of Rasmussen's Guide to the Birds of South Asia . The general public became aware of the scandal through an article in the New Yorker . The processing of the damage that Richard Meinertzhagen caused in ornithology continues.

literature

Literature from Meinertzhagen

Books on ornithology (selection)

- Nicoll's Birds of Egypt . 2 volumes. Hugh Rees, London 1930.

- Review of the Alaudidae . 1951.

- Birds of Arabia . Oliver & Boyd, Edinburgh 1954.

- Pirates and predators . Oliver & Boyd, Edinburgh 1959.

The Meinertzhagen collection is now in the Tring Zoological Museum .

The "Diaries"

- Army Diary. 1899-1926. Oliver & Boyd, London and Edinburgh 1960.

- Diary of a Black Sheep. Oliver & Boyd, London 1964.

- Kenya Diary. 1902-1906. Oliver & Boyd, Edinburgh 1957.

- Middle East Diary. 1917-1919. Cresset Press, London 1959, and Thomas Yoseloff, New York 1960.

These are excerpts from over 70 volumes with well over ten thousand pages of typewritten “diaries”. They are now in the Rhodes House of the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

Literature about Meinertzhagen

Obituaries:

- Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, CBE, DSO 1878-1967. In: The Geographical Journal . Vol. 133, No. 3, 1967, p. 429 f.

- Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen CBE, DSO 1878-1967. In: The Ibis . Vol. 109, No. 4 (1967), pp. 617-620.

Historical biographies of Meinertzhagen:

- John Lord: Duty, Honor, Empire. The Life and Times of Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen . Hutchinson, London 1971.

- Mark Cocker: Richard Meinertzhagen. Soldier, Scientist and Spy. Secker & Warburg, London 1989.

- Peter Capstick: Warrior. The Legend of Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, 1878-1967. St. Martin's Press, New York 1997.

Critical biography with the processing of his forgeries:

- Brian Garfield: The Meinertzhagen Mystery. The Life and Legend of a Colossal Fraud. Potomac Books, Washington, DC 2007, ISBN 978-1-59797-160-7 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ For example, quoted by Hew Strachan: The First World War. A new illustrated story . Pantheon, Munich 2006, pp. 114 and 116, from Meinertzhagen's diaries. It is almost the rule that they are used as a source in books on East African history, such as Geoffrey Hodges: Kariakor The Carrier Corps: The Story of the Military Labor Forces in the Conquest of German East Africa, 1914 to 1918 . Roy Griffin (Ed.). Nairobi University Press, Nairobi 1999, ISBN 9966-846-44-1 ; or Carl G. Rosberg, Jr. and John Nottingham: The Myth of 'Mau Mau' Nationalism in Kenya . East African Publishing House, Nairobi 1966.

- ^ Georgina Meinertzhagen: A Bremen Family . Reprint: General Books, Memphis, Tennessee, 2010, pp. 2 and 105f.

- ↑ The anecdote is mentioned in his obituary Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen CBE, DSO 1878-1967. In: The Ibis . Vol. 109, No. 4 (1967), pp. 617-620, here p. 617 repeated. Given Darwin's state of health at the time, it is extremely unlikely that the two of them would ever have met.

- ↑ According to information in his obituary: Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, CBE, DSO 1878-1967. In: The Geographical Journal. Vol. 133, No. 3, 1967, pp. 429f., He is said to have studied at the University of Göttingen.

- ↑ Grzimek's animal life. Vol. 13: Mammals 4. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1979, pp. 97f.

- ^ Brian Garfield: The Meinertzhagen Mystery. The Life and Legend of a Colossal Fraud. Potomac Books, Washington, DC 2007, p. 68.

- ↑ “Von Lettow is not going to fight it out. He will flit from pillar to post and occupy as many of us as he can. " Quoted from Garfield, p. 105.

- ↑ Garfield, p. 112.

- ^ Obituary: Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, CBE, DSO 1878-1967. In: The Geographical Journal. Vol. 133, No. 3, 1967, p. 429f .: “In 1916 he was transferred to Egypt as head of General Allenby's Intelligence Section and was responsible for the celebrated 'haversack ruse' before the third battle of Gaza, when he rode out into no-man's-land and, when chased by the Turks, pretended to be wounded and dropped a haversack containing money, various blood-stained letters and papers which gave skilfully-designed misleading information as to the direction of Allenby's attack. "

- ^ Friedrich Freiherr Kreß von Kressenstein : With the Turks to the Suez Canal . Otto Schlegel, Berlin 1938, p. 269. Kreß von Kressenstein attributes the deception to Meinertzhagen, as he found out from English sources after the war. For the Turkish view cf. Garfield, p. 256.

- ↑ According to Arthur Neate's diary (see below), Neate saw Meinertzhagen in his office on the afternoon of the alleged crash, cf. Garfield p. 33.

- ↑ The existence of MI-7 as a continuation of the real existing secret services MI-5 and MI-6 was often the object of parodies. However, during both World Wars there was actually an MI-7, in World War I under the Director of Military Intelligence , Major General George Macdonough . It was closed shortly after the end of the First World War and briefly revived in 1939. Meinertzhagen worked for this organization in both world wars.

- ↑ For example Martin Gilbert: The First World War. A Complete History. Henry Holt & Co, New York 1994, p. 370; Randall Gray: Chronicle of the First World War . Vol. 2. Facts on File, Oxford 1991, p. 94; Harold E. Raugh, Jr .: Intelligence . In: Military Heritage . April 2001, pp. 18-23. All information from Garfield, p. 253.

- ↑ Michael Occleshaw: Armor Against Fate. British Military Intelligence in the First World War and the Secret Rescue from Russia of the Grand Duchess Tatiana. Columbus Books, London 1989.

- ^ Obituary in Annie Constance Meinertzhagen . In: The Ibis . Twelfth Series, Vol. 4, No. 4, 1928, pp. 781-783.

- ^ Garfield, p. 168.

- ↑ War Memoirs of David Lloyd George . Vol. 6. Ivor Nicholson & Watson, London 1936, p. 3220: “[...] he struck me as being one of the ablest and most successful brains I had met in any army. That was quite sufficient to make him suspect and to hinder his promotion to the highest ranks of his profession. "

- ↑ Bo Beolens, Michael Watkins, Michael Grayson: The Eponym Dictionary of Mammals JHU Press, 2009, p. 31, ISBN 9780801893049

- ^ A b Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen CBE, DSO 1878-1967. In: The Ibis . Vol. 109, No. 4 (1967), pp. 617-620, here p. 619.

- ^ Brian Garfield: The Meinertzhagen Mystery. The Life and Legend of a Colossal Fraud. Potomac Books, Washington, DC 2007, pp. 187 and 309.

- ↑ “I can say upon my oath that Meinertzhagen's collection contains skins stolen from the Leningrad Museum, the Paris Museum, and the American Museum of Natural History. [...] He also removed labels, and replaced them by others to suit his ideas and theories. " Quoted from: Alan G. Knox: Richard Meinertzhagen - a case of fraud examined . In: The Ibis . Vol. 135, No. 3, 1993, pp. 320-325, here p. 320.

- ^ Alan G. Knox: Richard Meinertzhagen - a case of fraud examined . In: The Ibis . Vol. 135, No. 3, 1993, pp. 320-325, here p. 320.

- ↑ Knox: Richard Meinertzhagen ... , pp. 320-325.

- ↑ Knox: Richard Meinertzhagen…. P. 324f.

- ↑ Pamela C. Rasmussen and Nigel J. Collar: Major specimen fraud in the Forest Owlet Heteroglaux ( Athene auct.) Blewitti. In: The Ibis . Vol. 141, No. 1, 1999, pp. 11-21.

- ^ Sálim Ali: President's Letter 'Mystery' Birds of India - 3 Blewitt's Owl or Forest Spotted Owlet . In: A Bird's Eye View. The Collected Essays and Shorter Writings of Sálim Ali . Vol. 1. Permanent Black, Delhi 2007, ISBN 978-81-7824-170-8 , pp. 300–302, here p. 300.

- ^ Sálim Ali: President's Letter 'Mystery' Birds of India - 3 Blewitt's Owl or Forest Spotted Owlet . In: A Bird's Eye View. The Collected Essays and Shorter Writings of Sálim Ali . Vol. 1. Permanent Black, Delhi 2007, ISBN 978-81-7824-170-8 , pp. 300–302, here p. 302.

- ↑ John Seabrook: Ruffled feathers. Uncovering the biggest scandal in the bird world . In: The New Yorker . May 29, 2006, pp. 50-61, here p. 57.

- ↑ Rex Dalton: Ornithologists stunned by bird collector's deceit . In: Nature . Vol. 437, No. 7057, 2005, pp. 302f.

- ↑ Pamela C. Rasmussen: Guide to the Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. 2 volumes. Smithsonian Institution , Washington, DC 2006.

- ↑ John Seabrook: Ruffled feathers. Uncovering the biggest scandal in the bird world . In: The New Yorker . May 29, 2006, pp. 50-61. Seabrook describes Meinertzhagen's ornithological forgeries in this article, but still presents his claims about its historical role as fact.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Meinertzhagen, Richard |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British officer and ornithologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 3, 1878 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Kensington (London) , London, United Kingdom |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 17, 1967 |

| Place of death | Kensington (London) , London, United Kingdom |