Dialects in Saarland

| Saarland dialects | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

Saarland | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

Although there is no purely Saarland dialect, a wide range of dialect varieties is considered typical of the Saarland. In Saarland , both are Rhine Franconian and Moselle Franconian dialects spoken, all of the West Central German count. Colloquially, many Saarlanders refer to their dialect as " Platt ", often with a specification of the respective place (for example "Sankt Wendeler Platt").

distribution

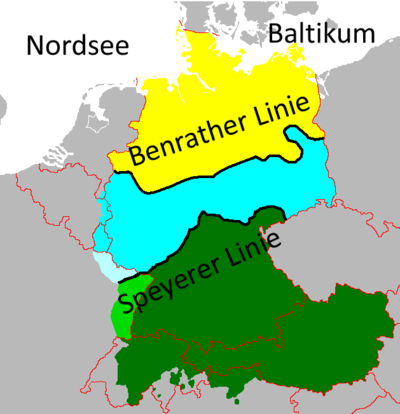

The language border between Moselle Franconian and West Palatinate Saarland follows the das-dat line ( Rhenish fan ), which runs through the country from Völklingen in the south-west to St. Wendel / Freisen in the north-east. Outside the Saarland, it is mainly the Rhineland-Franconian Saarland dialects, especially the “Saabrigga Platt” spoken in the state capital Saarbrücken , that are perceived as the Saarland dialect.

In the vicinity of Lebach and Schmelz , the “datt-watt” boundary runs along the Prims . Although no actual island dialect is spoken here, it remains to be seen that the Schmelzer dialect has certain peculiarities that do not occur in this form in the rest of the Saarland, since Schmelz is one of the last strongholds of the Moselle-Franconian dialect towards the Rhine-Franconian.

In allusion to the typical Moselle Franconian-Saarland expressions "lòò" (da, there) and "hei" (here), the area around Lebach and Schmelz in Saarland is referred to as the Lohei - especially among speakers of the city dialects .

There are also other smaller dialect islands in the Saarbrücken districts of Ensheim and Eschringen, as well as in Kleinblittersdorf - Bliesransbach and in Mandelbachtal - Blieshaben-Bolchen . In the local dialects there are forms that are characterized by the fact that the old monophthongs have not yet been diphthongized . This includes the dialects of Lorraine , which are otherwise only spoken in France, but are threatened by French there. It is true that an Alemannic origin or a transition to Alemannic is often wrongly postulated for all of these dialects ; In truth, these are marginal zones in which the High German diphthongization was not carried out - as in South Alemannic, Low German, some Thuringian dialects and Ripuarian .

historical development

The manifestation of the border lines (e.g. the course of the das-dat line from Völklingen to the northeast) can, among other reasons (such as the so-called homecoming limit), also be explained by denominational and political factors: The Rhenish-Franconian Before 1815, the language areas of the Saarland belonged mainly to the Protestant rule (e.g. the County of Saarbrücken and the Duchy of Zweibrücken ), while the Moselle-Franconian parts were significantly influenced by the Catholic Electorate of Trier . The Ensheim-Eschringer-Sprachinsel could also be traced back to such reasons, because Ensheim has belonged to the influential Wadgassen Monastery since the Middle Ages , and it is surrounded by Saarbrücken area. The observation that in the greater Saarbrücken area in the 17th and 18th centuries the dialect changed from Moselle-Franconian to Rhine-Franconian influence can probably be traced back to these conditions.

Another dialect border is attached to the home runner border to the south : only beyond this was it possible for the miners to reach their home villages on foot before and after the shift. During the industrial revolution, this area had its own language development that differed from the rest of the Saarland .

vocabulary

Examples

| Standard German | Saarland | |

|---|---|---|

| Rhine Franconian | Moselle Franconian | |

| Yes | jòò | jòò |

| No | nah | nah, nah |

| What? | what? / huh? | watt? |

| what for? | for what? / fawas / ferwas? | for watt? / fawatt? / fier wa (tt)? |

| I me you | isch / mixed / you, but also: me, me, you | eisch / meisch / deisch, ësch / mësch / dësch |

| you | you, de (unstressed) | dur, doo, de (unstressed) |

| Hello, how are you, what is your family / work / job etc.? - I'm fine, thanks for asking, and yourself? | Unn? - Jò, unn du / unn selbschd? / Unn selwer? | Onn? - Jó, unn selwat? |

| Potatoes | Grumberry / Grumbiere / Gromberry | Grompern / Grumbern / Krumpern / Grommberde |

| Carrots | Gellerriewe | Gellreiwen |

| cold | Freck | Freck |

| Suspenders | Galljäh | Galljäh, Gaul, Gaul |

| Rain gutter | Kannel, Kandel | Kaandel, Käänell, Kundel, Kòndel |

| learn, teach | teach | empty, lose |

| borrow, lend | lean, lean, lean, lean | lean, lean, lean |

| hide (something), hide (me) | (ebbes) verschdobbele / vaschdobbele, (mixed) verschdegge (le) / veschdegge (le) | clog / clog |

| to be afraid | gray | gray, ferten |

| ugly, unsightly | schròò | schròò |

| fast | dabba | siër / dapper, see |

| especially now | grad selääds ("just hurting") | grad selääds, express |

| fed up, sad / depressed | die / de Flemm hann, schnibbisch sin | de Flemm hann / hunn |

| look there | lu / gugg mòòl / emòòl dòò, gugg e mòòl dòò | l (o) u mò lòò, l (o) u mò lei |

| Siffy, ugly person | Pootsche / Pootche | Babbich Kerschdche |

particularities

holle and nemme

Many Saarlanders mostly use the word holle / hole ('to get') instead of the word nemme ('to take'). In large parts of the Saarland, take is almost completely replaced by fetch or only occurs in connection with prefixes ( abemme, mitnemme, in Moselle Franconian no longer: aafhollen, mëdhollen ). This has also been reflected in the (High German) local colloquial language, said Saar politician and Federal Minister (of Foreign Affairs) Heiko Maas in a daily news interview "You just have to get enough time for such a decision" (instead of "taking time") ).

- Examples

- Isch holl mei medicine (I take my medicine), also: I hòòl mei medicine

- Holl's dà only (take it easy ), also: Hòòl's dà nor

- I have picked up (I picked up, also: I picked up )

- Isch holl mich's Lëwwe / Lääwe (literally: I take my life, actually: I overexert myself), also: I hòòl ma's Lääwe

egg

A frequently used filler word without a direct meaning is the word egg. Similar to the English well, it is often used at the beginning of a sentence and cannot be translated. In particular, it also marks answers in retold dialogues and serves as a pause for thought before the actual answer.

- Examples

- Eijò (or drawn out in order to emphasize: Eijòòò )! / Ei jò! / Ei sëscher! (Yes certainly!)

- I’m going emmòòl gugge (I’ll have a look)

- And then it's frozen to see if Luschd still has it. - Eh! (Then I asked her if she was still interested. - No!)

Different place names

Many place names are pronounced very differently from the official spelling.

- Examples

- Altroff ( Niedaltdorf ) - the form -truff or -troff for places that end in -dorf in High German , continues across the state border to Lorraine and has been incorporated into the official spelling of the place names: Grosbliederstroff u. v. m.

- Daarle ( Saarbrücken St. Arnual )

- Däschdäasch ( Dörsdorf )

- Häschbre ( Hasborn )

- Kaltnaggisch ( male ear )

- Mäbinge ( Marpingen )

- Sietzert (Sitzerath)

- Berweld (Bierfeld)

- Wiwwelskeije (Wiebelskirchen)

- Moolschd (Malstadt) district of Saarbrücken

- Bätschbach (Bexbach)

- Heeb ( Hoof )

- Bräwatt ( Breitfurt )

Places with a “-weiler” at the end of their name (Ottweiler, Landsweiler etc.) are pronounced -willer / -willa (Ottwilla, Landswilla). In neighboring Lorraine, the pronunciation “-willer” is often used as an official place name.

The different pronunciation of the official place names also extends to place names in areas near the border of Rhineland-Palatinate , with which there is a dialect continuum :

- Laùätre or Laudd (e) re ( Kaiserslautern )

- Zweebrigge ( Zweibrücken )

- Baamella ( Baumholder )

- Sóuschett ( Grimburg )

Denominations of origin on -a

The denominations of origin of the inhabitants of places that end in -en (in the dialect -e ) are usually formed with -er (dialect: -a ) in Saarland , while the ending -ener is common in High German .

- Examples

- Dialect: Saarbrigge → Saarbrigg a

- High German: Saarbrücken → Saarbrück it (see also Saarbrücker Zeitung )

- Dialect: Neinkeije → Neinkeij a

- High German: Neunkirchen (Saar) → Neunkirch er (and not Neunkirchener )

but: Neunkirchen (Nahe) → Nin (g) keier - Neinkirier

- High German: Neunkirchen (Saar) → Neunkirch er (and not Neunkirchener )

- analogous to Dillingen , Zweibrücken , leases and so on.

- but: clearing → clearing a

- Tholey - Tholer not Tholeyer

- Hasborn - Häschber not Hasborner

- Berweller - beer fields

Exceptions

The rule is not applied to places outside the Rhine-Moselle-Franconian dialect area in whose region the -ener rule applies; in dialect it is called Dresd (e) na (Dresdner) or Minsch (e) na (Munich), but it is also called Erlang a (Erlanger) or Brem a . In other words - the educational rule applies at the place in question: Bremers are everywhere Bremer, Munich everywhere are Munich and Saarbrücken are everywhere Saarbrücken.

Tendency towards the diminutive

Similar to other dialects, there is a tendency towards frequent use of the diminutive .

First and last names

As in other southern German dialects (especially by older dialect speakers) third persons, i.e. those who are not present, are usually named with a preceding family name: “De Meier Kurt”, “Meiersch Hilde”. It should be noted that the maiden name or maiden name is also used as a gender name for married women. Mrs. Hilde Becker b. Meier is "Meiersch Hilde" until the end of her life, because she comes from the Meier family, and not "Beckersch Hilde".

French influence

For centuries the Saarland was a plaything of interests between Germany ( Prussia , Bavaria and others) and France . In addition to some French place names, influences on the Saarland vocabulary also come from this period.

| German | Saarland (Rhine or Moselle Franconian) | French origin |

|---|---|---|

| Duvet, duvet | Plümmo | plumeau ( down duvet, down comforter ; from plume = feather ) |

| pavement | Troddwa / Troddewa / Trottuar | pavement |

| head | Daätz | tête |

| quietly, (also: take it easy) | dussma (now do mòl dussma) | doucement |

| on, go, hopp! (also: bye!) | allé (alleh / alláa then!) | all (go) |

| be grumpy | d (i) e Flemm hann | avoir la flemme (too lazy to do something) |

| easy, humorous | klòòr | coloré (couleur = color ) |

| sofa | Schess (e) long | chaise longue |

| Stroller / K. drive | Scheesewään (s) che / (rum-) Scheese | also refers to chaise = chair |

| Eaves, drain | Kullang | couler (drain) |

| wallet | Portmonnää / Portmonnäi | Wallet |

| back | rèduur [-'-] | back |

| are in a hurry | pressiere (me pressiert's) / pressere (mer pressert's) | presser |

| bailiff | it Hissje | huissier |

| to go to your loved one, free | puss / posseere (walk) | pousser = press |

| I'm cold | I han (have) cold | j'ai froid |

| umbrella | Parapli | parapluia |

| Currants | Groan | groseille |

Notation

As with other German dialects, there is no standardized written language. Dialect authors write the Saarland dialect phonetically (according to the pronunciation) in an adapted German spelling. An additional letter is required to separate the long open O [ ɔː ] from the long closed O (see below, Phonetics section ): For this purpose ò or òò (to emphasize the length) is written. The spelling å , which is often used in the Bavarian language for a similar sound, is only used very rarely. In addition, the "ë" (roughly between ö and ë) is used in the Moselle Franconian dialects as in the neighboring and related Luxembourgish.

phonetics

Since the exact pronunciation usually varies from village to village, the rules mentioned in the following section do not necessarily apply to all regions. There are differences in particular between the Rhine-Franconian and Moselle-Franconian dialects.

Consonants

The inland German consonant weakening is characteristic of Saarland . H. the neutralization (phonology) of the difference between voiced and unvoiced consonants. This means that for speakers of Standard German, especially at the beginning of the syllable, actually voiced consonants can be perceived as voiceless and vice versa.

Consonants are usually pronounced somewhat voiced (e.g. in La dd ezòn, “La tt enzaun”), which is usually also given in writing. Conversely, is a clearly perceptible at typically loud induration place at groups of consonant + / r / at the beginning of a syllable. For example, for Saarlanders, the pronunciations [ pʁoː'ɡʁam ] and [ bʁoː'kʁam ] of the word program are allophone (that is, from a phonetic point of view, one could just as easily write Brokramm - this would not change the pronunciation or not perceive it). However, such initial hardening is usually not reflected in writing. It can also be found in other German dialects.

Also typical Saarland is the failure to distinguish between sh [ ʃ ] and soft ch [ ç ] ( ch as in white ch , not like in Lo ch ): Both phonemes are in large parts are Saarland and allophone pronounced as a relatively soft, almost voiced sh . This sound, a alveolopalataler fricative [ ɕ ] , lies between the standard German sh and ch . This allophony means , for example, that the words church and cherry are both pronounced as Kersch / kɛɐɕ / and can only be distinguished on the basis of the context .

The sound values for ch (as in Lo ch ) and r seem to be closer together than in many other regions of Germany. The manifold varying in the German pronunciation of r can be in the Saarland almost the voiced pronunciation of the ch ( [ ʀ ] instead unvoiced [ χ ] or [ x ] coincide), z. B. about raare [ ʁaːʁɘ ] (Eastern Saarland for smoking ).

Similar to the Low German and the Rhine Franconian and especially the Mosel Franconian have some of the sound shifts of standard German not participate:

- The consonant combination pf / PF / in High German words is in Saarland basically pp, z. B. in Kopp ("head"), Päär ("horse") or Abbel ("apple"). This is characteristic of dialects north of the Speyerer line / Main line .

- The pronunciation of the b changes intervowel to w , e.g. B. e Wei b , zwää Wei w he ( "a Wei b , two Wei b er") or weewe ( "weave"). In such cases, the pronunciation of this w can be a kind of mixture of b and w ; it is almost a b , in which the lips are not fully closed ( [ .beta. ] ). This fact is remarkable insofar as the Saarland should actually lie south of the Boppard line . In the Moselle-Franconian part of the Saarland, this also happens in the wording, e.g. B. Korf as opposed to Korb .

- Conversely - in the Rhine Franconian part - a w can mutate into a b in the wording, e.g. b. in e Lee b , zwä Lee w e, e Lee b -specific ( "a Lö w e, two Lö w s a Lö w Chen"). Also in this case, the debate is the w blurred and tends to [ beta ] .

- In Moselle Franconian there is also a systematic use of t instead of s , depending on the context , e.g. B. wa t ? (“What?”), But not in Rhine Franconian. This difference is the main distinguishing feature between Rhine-Franconian and Moselle-Franconian Saarland; the border between the two dialect groups is therefore called the / dat line (also: Sankt Goarer line or Hunsrück barrier).

Vowels

In the standard German only exist two pronunciations for O, namely, a short open / ɔ / (z. B. " o ffen") and a long closed / O / (z. B. "gr o ß") . Saarland also knows another one, namely the long open o / ɔː /, often written as òò . This is typically used in place of a long a , e.g. B. in klòòr ("interesting"; actually "clear" [in some regions, however, klòòr also stands for funny or surprising, for example: that iss jo klòòr = that is weird / strange]) or in hòòrisch ("hairy “), But not in large [ kʁoːs ] , for example .

According to the east (in the standard German depending on the length [ O ] or [ œ ] ) exists in the Saarland not native ( Entlabialisierung ). Long ö will ee [ ê (z. B.] sch ee n "sch ö n"), short ö becomes e and the like [ ɛ ] (z. B. W e rda "W ö rter ").

Likewise, there is no ü in Saarland . It is in most cases by i replaced (eg in. I wwa " ü ber", Eq i gg "Gl ü ck"), with a short i is often spoken in the initial sound a bit dull with a hint of rounding; about [ ɨ ] (or even [ ʉ̟ ]). However, there is not always a replacement by i , e.g. B. H u ndsche (H ü DOGGY) or in dòòdef òò r (daf ü r).

In addition, many Saarlanders speak mixed sounds with a tendency towards Schwa instead of short closed and semi-closed vowels, i.e. between short "i" and "e", e.g. B. “/ nɪt /” → “/ nɘt /” → “/ nət /” (not), as well as between a short “o” and “u”, e.g. B. "/ ʃʊlːɐ /" → "/ ʃɵlːɐ /" → "/ ʃəlːɐ /" (shoulder). The transitions are fluid and the use varies between regions and people.

Diphthongs

Also typical of the Saarland is the often somewhat more closed and further forward rendering of the diphthongs ei as [ ɐɪ̯ ] (instead of [ aɪ̯ ]) and au as [ ɐɵ̯ ] (instead of [ aʊ̯ ]).

The diphthong eu does not exist in Saarland, but is replaced by ei (or au, depending on the region), e.g. B. in egg or auer “your” or nei (also nau ) “new”. If it is pronounced consciously, for example to clarify a statement through High German pronunciation, it is typically given locally colored rather than [ ɵʏ̯ ] or [ ɵɪ̯ ] (instead of High German [ ɔʏ̯ ]).

All in all, the Saarland dialects are characterized by a largely poor diphthong. Many words that have a diphthong in High German simply have a vowel in the Saarland at the corresponding point. If a diphthong is replaced by a vowel, this happens more or less regularly; however, there seems to be no rule which determines in which cases the diphthong is replaced and in which not. Here is a presumably incomplete list:

- ei → [ ɛː ] or [ ɛ ] : kää or label (depending on the region) for "no"; analog "small"

- ei → [ ə ] / [ ɘ ] : e for "on".

- au → aa / òò: laafe or lòòfe (depending on the region) for "to run". Analog "buy", "tree"

- au → u / o: uff, also off (depending on the region) for "on".

- au → ou: Schlouch for "hose", Bouch for "belly" (mainly for older speakers)

It should be noted in particular that the substitutions of one and the same diphthong can also be different within a region, e.g. B. u ffk aa fe ( au fk au fen) or R ä n ( e ) m ( " clean home ", place name, from the verb rääne rain =; the e is as extremely short [ ə ] pronounced) .

Klitika

As in many other dialects, pronouns and articles in particular , but also sometimes other unstressed words, merge with preceding or following words; they get clitical .

- (Extreme) examples

- Hann ersm sowed? - "Did you tell him ?" (Triple clitical)

- Unn s has ne frozen, obb ers do dääd. - "And it (= she) asked him if he would do it." (Both proclitically and enclitically)

Syllable stress

The emphasis on the individual words largely corresponds to that of the standard German language. However, in some cases - especially with place names - there are deviations from the norm; the tendency then is to stress the first syllable. Examples: Zwääbrigge ( Zweibrücken ) and Neinkeije (also Näinkaaje ) ( Neunkirchen ). The words cocoa or nutmeg are also emphasized locally on the first syllable.

The pronunciation of French terms regularly differs greatly from the original French; they merge seamlessly into the dialect by adjusting both the sound value and the accentuation. Sometimes the stress shifts to the first syllable.

Final syllables

The differences between High German and Saarland final syllables are also regular in many cases:

- Unstressed -en almost always becomes -e in Rhine Franconia , e.g. B. in all verbs (laugh → laugh, eat → eat, wash → laundry, let → go ; exceptions: go → go n , see → see n ), but also in plural forms (lanterns → laderne ) and other cases (cart → Karre ), even with place names ( Munich → Minsche, Dillingen → Dillinge ). This applies i. A. but not for the (southwest) Moselle Franconian.

- The word component -agen usually becomes -aan: say → s aan , wagon → w aan , hit → schl aan .

- Other unstressed -n is either omitted in Rhine Franconian (seldom, especially in the dative case , see grammar ) or is interpreted as high German -en and thus according to the above rule to -e , e.g. B. in traffic light n → Ambel e . The local Moselle Franconian is also normally exempt from this rule.

grammar

Apart from the pronunciation, there are a number of grammatical and semantic differences to everyday German.

Neutral feminine

In Saarland, women have the neuter as their grammatical gender. For example, Saarland does not use the forms Anna or Hilde commonly used in "normal" colloquial language , but rather it Anna ("das Anna") or es Hilde ("das Hilde"). Which is especially at the start of the block it in this case usually to a single s reduced, so that this also phonetically interesting constructs such as s Susanne yield / s‿su'sʌnə / (the distinction between voiced and unvoiced consonant is weak, the article is klitisch , see above). The use of ähs dòò or et lòò , literally translated as "she there", is also often used , but with a mostly derogatory connotation .

This peculiarity of "neutral women" is not due to a disdain for women, but rather comes from the fact that " the girl " and " the miss " are grammatically neutrals: the Saarlanders see almost all women as girls / misses. Female speakers do not avoid this rule either.

Married women are an exception. If not the first name but the (newly acquired) surname of the husband (with the possessive suffix -sch ) is used, the woman is grammatically feminine: " es Hilde" - but " die Bäggasch" (the "Becker'sche" = the wife of Mr. Becker). (S. the (!) Woman).

Another exception are women - regardless of their marital status - that are gesiezt or referenced with their surnames: " The Mrs. Muller has gesahd" - and subsequently also " it has also gemennt".

The neutral feminines of Saarland are not unique; the same can be found in the Cologne dialect and beyond.

conjugation

In the present plural there is basically only one verb form for all three persons: mir sinn, you sinn, die sinn (instead of “we are, you are, they are”).

As in many other southern German dialects, a past tense is not in use. The verbs hann (have) and sinn (be) are an exception ; however, the past tense forms are sometimes only used as an auxiliary verb to form the past perfect . For example, the choice of words Isch hott geschdern kää problems ('have' in the simple past) would be more common; More common is the use of the perfect perfect: Isch hann schdern kää had problems or past perfect: Isch hott schdern kää had problems .

Conversely, as is common in other regions, the superplusquamperfect is often used: He hott mers gesaat hat (RF) "He had told me". (Note: In High German, “He told me” (perfect), “He told me” (past tense) and “He had told me” (past perfect) are grammatically correct.)

Analogous to standard German, the analytical subjunctive forms ( isch hann → isch hätt , isch krien → isch kräät ) are increasingly being displaced by verbal constructions. The subjunctive II is formed in most cases with the help of the subjunctive of the verb duun ("to do"), in some regions also go ("to go"): isch dääd saan, that ... or isch passt (d) saan, that ... ("I would say that …"). In the standard German language, the use of dääd / passt (d) corresponds to the use of would. Duun (“to do”) is used almost exclusively in this function as an auxiliary verb ; otherwise, the use of mache has established itself for the verb “to do” . The subjunctive I, which is used in standard German in indirect speech, actually does not exist (as in many other German dialects) or, especially if the speaker doubts the truth of the recounted statement, is replaced by the subjunctive II or verbal constructions with dääd / gang ( d) substituted.

The use of the verb genn (to give) instead of werre (to be) is also widespread, although not entirely consistent . Werre is used almost exclusively as an auxiliary or modal verb . Both the formulation Moo egg moment which is so never gesaat genn and egg moment moo, the Sun never is gesaat wòòr (both: "Yes (≈ egg) Wait a minute, that was never said so") are accepted. Overall, it can be said that genn is accepted for the formation of the passive and as a main verb substitute for to be , but is not or only rarely used to form the future tense . Examples: It gebbt nächschde month zwää ( "It (= they) will next month two (years old)"); on the other hand: I werre sem not verròòde ("We will not tell him / her").

The conjugation of some verbs uses other forms than in standard German, for example isch hann gebrung (instead of “I have brought”), or isch hann das net gewissen (instead of “I did not know”), sometimes a different form of first person singular of meaningful when used as an auxiliary verb: achzeh genn as ish sense ( "when I eighteen (years old) , where (= become) am )".

The latter can also be explained by the peculiarity of Saarland, that the first person singular (as well as all plural forms) coincides with the infinitive. The conjugation table for the indicative present active is as follows for Saarland (including examples: go "go", hann "have", gugge (n) "look" / "look", chat (n) "talk"):

| step | Infinitive to -n | Infinitive to -e (Rhine Franconian) | Infinitive in -n (Moselle Franconian) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard German | go | to have | watch | talk | watch | talk | |||

| infinitive | (Forming) | go | hann | (Forming) | gugge | chatter | (Forming) | look | chatter |

| 1st person singular | -n | I'm going | i'm hann | - | I gugge / look | chatter | -n | look ësch / eisch | ësch / eisch babble |

| 2nd person singular | -sch or -schd | you go (d) | you hash (d) | -sch or -schd | you guggsch (d) | you schwäddschd | -schd | doo / dah guckschd | doo / dah babble |

| 3rd person singular | -t / -dd | he / she / it goes | he / she / it hadd | -t / -dd | he / the / it guggd | he / it chatters | -t / -d | (h) en / he / (h) ett peep | (h) en / he / (h) ett chatters |

| 1st person plural | -n | go to me | me hann | -e | me gugge | chatter to me | -n | look at me | talk to me |

| 2nd person plural | -n | you go | you hann | -e | you gugge | you chatter | -t / -d | look at you | you chatter / chatter |

| 3rd person plural | -n | they go | the hann | -e | the gugge | the chatter | -n | look se / sée | se / sée chat |

declination

The distinction between the Kasūs has largely disappeared in Saarland:

- The dative does exist as a case; The nouns are usually not changed in the dative when declining , only the article provides information: z. B. die Kinner, de Kinner ("the children, the children n ").

- The accusative is generally replaced by the nominative . Only the definite article reveals the accusative (especially with younger speakers). See. Hash you the doo Liar Liar geheerd? (“Did you hear the dumbbeater there?”); but also more and more often: hash you denne foolish talker dòò geerd? The deviating declension of the noun becomes clear especially with (also substantivated) adjectives, e.g. B .: "Isch hann e scheen a Schingge doo" ( " beautiful he " instead of High German dekliniertem "I have a beautiful en ham here"); or also: "Isch hann e Pladda." (" Platt er ") instead of the high German declined "I have a Platt en (tire)."

- The genitive does not exist. Instead of the genitive, as in many other regions of Germany, there are usually dative constructions: Either with the preposition "von", z. B. He is de Schwòòer vum Chef. (“He's the boss's brother-in-law.”) Or as an anticipatory dative construction with sumptive possessive pronouns , e.g. B. em Hilde sei Schwòòer (literally: "to Hilde his brother-in-law"; analogously "Hilde's brother-in-law").

Diminutive

There are three diminutive forms . Usually the simple forms are used on -je and -sche , e.g. B. Wutz → Wutz each (pig / pig) or Waan → Wään specific (vehicle / carts). The high German -chen corresponds to these two forms . Diminutive forms on -le such as B. in Alemannic or -lein in High German are not used.

However, in addition to the forms -je and -sche, there is also a rarer third form of the diminutive on -elsche, e.g. B. Wutz elsche (roughly equivalent to "particularly cute little pig"). This third form is a particularly strong form of the diminutive; In High German it would correspond to the simultaneous use of -lein and -chen in the same word.

Occasionally there are also diminutive-like constructs in verbs , e.g. B. in rumwutz el e (from rumwutz ), which, as with nouns, can soften the sharpness of a statement and provide it with a wink.

The diminutive in the Saarland dialect features compared to the standard Deutsche its own plural form : The last letter of the extension is very open and corresponds to the pronunciation of standard German suffix -er (which normally as [ ɐ ] is pronounced). Examples: e Bäämsch [ ə ] → zwää Bäämsch [ ɐ ] (tree), e Mädsch [ ə ] → zwää Mädsch [ ɐ ] (girls).

Pronouns

Similar to Dutch, there are two forms for many pronouns, a stressed and an unstressed, of which the unstressed is usually used.

| Nominative | dative | Remarks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard German | unstressed | stressed | ||||

| I | isch, sch | isch / esch (MF) | me | mer | me | |

| you | de | you (RF) / last (MF) | to you | there that | to you | |

| he | a (very short "er") / (e) n (MF) | der, he (long) / henn (MF) | him | m, em, nem, himm | demm, dem | |

| she | se | die (rarely: she) / hett (MF) | her | ner, rer, he, hiir, army | of the | Rare; see. Note above about grammatical gender! |

| it | s (RF) / et (MF) | uhs, das (RF) / dat, et (MF) | him | m, em, nem | demm, dem | Usually replaces the feminine form, s. O. |

| we | mer | me | us | oos, us | ||

| her | ner / der (MF) | you (MF) | to you | eesch, eisch | Also common form of courtesy | |

| she | se | die (seldom: she) / be (plural only), she (seldom) (MF) | them | ne, en, hinnen | dene, dene | |

The pronoun she (says) and se (unstressed) is used only for the third person singular femininum - but which is rare because of the grammatical neutrality of women - and for the polite form to the address.

This 3rd person singular feminine (“die”, “she” or “se”) is normally used for women who are named by their surname (“se” for “the woman Müller”), or for only grammatically feminine things (“ se ”for“ die Bluum ”= flower) as well as salutations / (job) titles / titles (“ se ”for“ die Mudder ”= mother).

As a personal pronoun for the 3rd person plural, however, it is not used or only rarely used; typically one uses the as an accented form instead . The unstressed shape se (with a very short [ ə ] ) can also occur for the third person plural, but usually only in enclitic position z. B. in Hann se dir sellemòòls kää money gebb? - "Didn't they give you any money back then?"

The adverb dòò (high German da in the sense of here, there; but not in the sense of because ) can also be used attributive or pronominal (but here it is not inflected ), whereby the sentence order usually changes as follows: The dòò audo fallen mer aarisch gudd. - " I like that car (= this car) pretty much." The combination of certain articles + dòò thus replaces the demonstrative pronouns that are not used in Saarland.

Word order

In the case of constructions made up of the auxiliary verb plus the infinitive of a main verb, in which the auxiliary verb is at the end of the sentence in High German, this changes position in Saarland with the main verb. Examples are the unrealis of the past ( Jòò, that hättma kenne mache. - "Yes, you could have done that.") And subordinate clauses ( Hatma jòò kenna gesaad, that I should go ahead. - "Nobody told me, that I should let her go. "). This word order can also be found, for example, in Dutch and various Alemannic dialects .

Connections with have and adjective

Similar to French, Saarland often uses the combination of haben with an adjective, e.g. B. isch hann kald ( I am cold = I am cold) like French j'ai froid .

literature

- Edith Braun : Max and Moritz in Saarbrücker Platt (adaptation of Wilhelm Busch's Max & Moritz). Saarbrücken 1983, ISBN 3-922807-33-X , 64 pages, out of print.

- Edith Braun, Max Mangold : Saarbrücker Dictionary. Vocabulary of the current Saarbrücken vernacular. Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag, 1984, ISBN 3-921646-70-7 , 304 pages.

- Edith Braun: Saarbrücken dialect lessons. Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag, 1986, ISBN 3-925036-06-7 .

- Edith Braun: Saarbrücker Homonym Dictionary. Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag, 1989, ISBN 3-925192-92-1 , 373 pages.

- Edith Braun: nicknames of the Saar and around it. 2nd Edition. Lebach, 1991, out of print.

- Edith Braun: Dialect. Dictionary - Stories - Customs. Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag, 1994, ISBN 3-925036-89-X .

- Edith Braun: New Lebacher dialect book. Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag, 1995, ISBN 3-930843-00-5 , 224 pages.

- Edith Braun: When someone from Saarland says. Ottweiler Druckerei, 1995, ISBN 3-923755-44-9 .

- Edith Braun, Anna Peetz: Hare bread and goose wine. All kinds of food and drink. edition Karlsberg, Homburg / Saar 1995, ISBN 3-930204-07-X , 312 pages.

- Edith Braun: Lively dialect. Gudd gesaad I. Proverbs and sayings. Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag, Saarbrücken 1996, ISBN 3-930843-04-8 .

- Edith Braun, Lutz Hahn: Lively dialect. Gudd gesaad II. Proverbs and sayings. Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag, Saarbrücken 2000, ISBN 3-930843-59-5 , 160 pages.

- Edith Braun, Adelinde Wolff: Dialect of Werschweiler / Ostertal. Words and stories. Verlag Pirrot, Saarbrücken-Dudwei1er 1997, ISBN 3-930714-27-2 .

- Edith Braun, Max Mangold, Eugen Motsch : St. Ingbert dictionary. Verlag Pirrot, Saarbrücken-Dudwei1er 1997, ISBN 3-930714-30-2 , 236 pages.

- Edith Braun, Karin Peter: Saarlouis dialect book. Dictionary - Stories - Customs. Saarbrücken printing and publishing house, Saarbrücken 1999, ISBN 3-930843-47-1 .

- Edith Braun: The Saarland Christmas story. Verlag Michaela Naumann, Nidderau 1999, ISBN 3-933575-20-6 , 16 pages.

- Edith Braun, Agnes Müller, Rainer Müller: Quierschieder dialect book. Dictionary - Stories - Customs. 2002, ISBN 3-923755-90-2 .

- Norbert Breuer-Pyroth: Vaschtesche me? Dictionary of the old Saarlouis language. Vocabulary with 1,400 terms. With 62 pages of stories. 4th, greatly expanded edition. Saarlouis 2006, ISBN 3-00-020012-6 , 181 pages.

- Georg Drenda: Word atlas for Rheinhessen, Pfalz and Saarpfalz . Röhrig Universitätsverlag, St. Ingbert 2014, ISBN 978-3-86110-546-6 .

- Horst-Dieter Göttert : How mæ héi gossip. Beckinger Sprachgut. A Moselle Franconian dialect dictionary. Beckingen 2010, 422 pages, 87 illustrations, hard cover.

- Wolfgang Haubrichs u. Hans Ramge (Ed.): Between the languages, settlement and field names in Germanic-Romanic border areas, contributions to the language in Saarland, 4, Saarbrücken 1983.

- Frank Lencioni: Practical language course Saarland. 2nd, expanded edition. Books on Demand, ISBN 978-3-8423-3067-2 .

- Charly Lehnert , Gerhard Bungert : So chat to me. Phrase book High German-Saarland. Phrases, vocabulary, grammar. Lehnert Verlag, Saarbrücken 1987, ISBN 3-926320-09-5 , 96 pages

- Charly Lehnert, Gerhard Bungert: Hundred words Saarland. Key vocabulary. Lehnert Verlag, Saarbrücken 1987, ISBN 3-926320-11-7 .

- Charly Lehnert: Hundreds of Saarland wisdom. Saarland idioms in Rhine-Franconian and Moselle-Franconian dialect. Lehnert Verlag, Saarbrücken 2003, ISBN 3-926320-80-X , 36 pages.

- Charly Lehnert: DerDieDasDòò. Saarland idioms in Rhine-Franconian and Moselle-Franconian dialect Lehnert Verlag, Saarbrücken 2003, ISBN 3-926320-77-X .

- Alexandra N. Lenz: Structure and dynamics of the substandard. A study on West Central German ( Wittlich / Eifel ). Stuttgart 2004.

- Hans Ramge: Dialect change in central Saarland. (= Publications of the Institute for Regional Studies in Saarland, Volume 30), Saarbrücken 1982, 24 maps, ISBN 978-3-923877-30-0 .

- Manfred Vogelgesang: The dialect of Blieshaben-Bolchen (Saarland). In: Phonetica Saraviensa (11). Saarbrücken 1993.

Web links

- Dialect and dialect literature in Saarland

- Literature on the Saarland dialect in the Saarland bibliography

- Gau un Griis Association for the maintenance of Franconian in Lorraine. Founded 1986. Has been operating since 2001 a. a. publishes the biannual trilingual (Français, Deutsch, Platt) literary magazine "Paraple". Currently at number 37 (80 pages each)

- Saarland dictionary (private collection)

- Stefan Abenschön: 50 Joor Saarland: Mainly gutt gess - From the house and feasting of the Saarlanders (HBK Saar) , youtube

- Geoplatt ( Memento from November 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Page with a map of the das-dat border ( memento of the original from March 28, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Page on the history of the Saarland dialects ( Memento of the original from March 28, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Saarland for Beginners ( Memento from October 11, 2012 in the Internet Archive )