Saint-Joseph (Montigny-lès-Metz)

Saint-Joseph is a Roman Catholic parish church in the Lorraine community of Montigny-lès-Metz in the Moselle department in the Grand Est region of France . The St. Josephs Church was built during the time that Montigny belonged to the German Empire ( Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine ). It is assigned to the diocese of Metz . The main day of patronage is the ecclesiastical solemnity of Joseph of Nazareth ( March 19 ). The two additional patron saints of the Josephskirche are Saint Anthony of Padua (memorial day: June 13th) and holy Privatus of Mende (memorial day: August 21st). Both saints recall the patronage of the two previous churches of Montigny.

history

After the annexation of Metz to the German Empire after the Franco-Prussian War in 1870/1871 and the subsequent peace treaty of Frankfurt , the city on the Moselle became the administrative seat of the newly created district of Lorraine within the realm of Alsace-Lorraine (with the capital Strasbourg ) . In addition, Metz was developed into the strongest fortress city ( fortress Metz ) in the German Empire. Before the Franco-Prussian War , Metz had 47,242 inhabitants, of whom only 1952 had given German as their mother tongue. The majority of the population was of the Catholic denomination, the Protestant community had around 1,000 members and the Jewish community had 1952 members.

By 1910, the city grew to a total of 68,598 inhabitants due to the influx of so-called "old Germans" and members of the military. The population growth between 1905 and 1910 was also a result of the 1908 amalgamation of Plantières-Queuleu and Devant-les-Ponts, which together contributed 7,639 inhabitants. With regard to the population of 1910, only 20,932 people were born in Metz itself, 15,432 came from the rest of the Reich, 14,521 had moved from old Germany and 4080 came from abroad.

As a result of the emigration of some of the residents to France and above all through immigration and the stationing of German officials and military, the previously mostly French-speaking Metz temporarily became mostly German-speaking.

After the annexation of Germany, Metz was redesigned by the German authorities, who decided to turn urban planning into a kind of architectural 'showcase' for the German Empire. As a result, the previous old defensive walls around the city center were laid down, a new infrastructure laid out and the area rebuilt for residential and commercial purposes.

The architectural eclecticism is reflected in numerous historicist , especially neo-Romanesque buildings, such as the Metz train station , the Protestant city church Metz and the main post office. The imposing Protestant garrison church of Metz with its 97 meter high church tower was built in neo-Gothic style. In addition, the Gothic cathedral of Metz was extensively redesigned .

In 1817 Montigny only housed 848 inhabitants in 108 houses, after 1871 it became an important garrison town with strong population growth. In 1910 Montigny had 10,260 inhabitants. A new church had already been built for the Protestant residents in 1894, so that the Catholic majority of the community population did not want to stand back and began to collect donations for a new church under the pastor Zutterling. Until then, the residents of Montigny attended services in the small local parish church, which was dedicated to the holy private of Mende . The old parish church was on the former Chausseestrasse (today Rue de Pont-à-Mousson) in the area of today's Place de la Nation, west of today's Josephskirche.

There was also the monastery church of St. Anthony of Padua , which was mainly intended for the nuns of the local Benedictine abbey and was expanded in the 17th and 18th centuries. The urgency of building a new church was declared by a resolution of the parish council on April 24, 1898. The new church in Montigny was no longer to stand at the old location, but was to be built elsewhere. The relocation of the new parish church to another place was due to the fact that the former location on the main street of Montigny had led to constant noise during the services due to traffic noise and troop movements and it was now hoped that the cult would take place undisturbed.

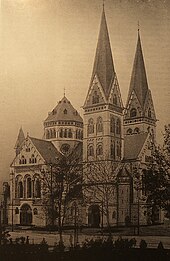

The foundation stone of the new church building in Montigny took place on May 3, 1903 at the site of the earlier orchards. The neo-late Romanesque St. Joseph's Church, built by Ludwig Becker in Montigny near Metz between 1903 and 1906, is directly linked to the architecture of the Koblenz Herz-Jesu Church . According to an article in the Metzer Zeitung, the pastor of Montigny, Philipp Châtelain, pastor Zutterling's successor in office, had seen the plans of the Sacred Heart Church on display in Koblenz in 1899 and was so enthusiastic about them that he commissioned Becker for there was a similar church in Montigny. Ludwig Becker was also a member of the Metz Cathedral Building Association and thus part of a local network with regard to church building.

The church in Montigny was inaugurated on Sunday, July 29, 1906 by the Metz bishop Willibrord Benzler .

The church, which had previously been neglected in maintenance, was extensively restored in 2017 by a resolution of the Montigny city council.

architecture

The sacred building, built in the Rhenish-Romanesque style of the 12th century by the Mainz cathedral master builder Ludwig Becker, with a high west tower flanked by a staircase tower of 72 meters high, a narthex and a richly structured choir section with choir flank towers, is clearly based on the architecture of the interior and exterior Cologne Church of St. Apostles . A large main portal with eyelashes and a rose window above it leads into the interior. The side aisles are accessible through two smaller portals on the main facade. A statue above the rose window represents the church patron, Saint Joseph.

The design of the free floors of the facade tower reveals the architect's extensive knowledge of the history of architecture. Becker designed the tower in a balanced way and conceived his designs in Montigny and elsewhere as historical buildings that, despite their perfection in execution, suggest a longer construction period with a change in construction and style phases to the viewer. Becker implemented this knowledge consistently in the immediately preceding project before Montigny, in Mettlach with the construction of the neo-Romanesque Lutwinus Church (1899–1901). Early Romanesque and late Romanesque design elements of the Rhenish transition style are skillfully combined. To increase the imposingness of his tower facade in Montigny, Becker does not use a rhombus helmet for the tower helmet, as a concept based on the historical original would actually have required, but crowns his bell tower with a high octagonal slate helmet, which is already based on the Gothic design language. The conception of the tower cubature with its high gables and the pointed helmet is based on that of the towers of Lübeck's Marienkirche .

As with Becker's church building of St. Lutwinus Church in Mettlach, the neo-Romanesque Elisabeth Church in Bonn (1906–1910) and the Koblenz Herz-Jesu-Kirche in use, stone-transparent elements and plastered surfaces alternate in Montigny. In addition, roughly hewn stone is scattered into the facade in order to avoid any impression of over-smooth, boring perfection. The sprinkling of rustic ashlar in the facade of the Josephskirche in Montigny creates organic transitions between plastered surfaces and ashlar surfaces. Becker deliberately breaks up the canonically strict neo-Romanesque conception of Rhenish-Romanesque influences and thus finds intellectual connections to the painterly-organic conception of Art Nouveau .

Architectural elements from the late Staufer period , i.e. the first half of the 13th century, were used in Becker's neo-Romanesque churches in Mettlach, Koblenz, Bonn and Montigny . After the founding of the German Empire with the victory over the French Empire in 1871, the Staufer myth experienced a great boom. Emperor Wilhelm I was occasionally called Barbablanca ("white beard"), analogous to the nickname Barbarossa ("red beard") of the Hohenstaufen emperor Friedrich I. Wilhelm I as the perfecter of the policy of Friedrich I. Barbarossa - this idea was born in 1896 For example, staged in its purest form in the neo-Romanesque Kyffhäuser monument . According to legend, Barbarossa slept in the Kyffhäuserberg only to wake up one day and save the empire.

Under the special influence of Kaiser Wilhelm II , buildings were built everywhere in the German Empire based on the style models of the Rhenish Romanesque, which, in addition to their sacred or profane function, above all a monument character in the sense of emphasizing the connection between medieval and current size and importance of the empire should express. In a historicizing architectural language, Kaiser Wilhelm II tried to build on the heyday of the German emperors of the Middle Ages. Since 1889 in particular, the emperor has been intensively concerned with the Romanesque churches of the Rhineland in Gelnhausen , Limburg , Maria Laach , Andernach , Sinzig , Bonn , Schwarz-Rheindorf and the Romanesque churches of Cologne . A specially created collection of building photographs and architectural details were presented to the well-known architects of the German Empire, as the Emperor considered the Romanesque architectural style to be particularly capable of development.

The results of the imperial efforts were the construction of prestigious neo-Romanesque buildings such as the Berlin Gnadenkirche (1890–1895, Max Spitta ), the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church with a neo-Romanesque forum (1891–1895, Franz Schwechten ), the Church of the Redeemer in Bad Homburg in front of the height (1903–1908, Franz Schwechten), the Church of the Redeemer in Jerusalem (1893–1898, Friedrich Adler ), the Dormition Basilica on Mount Zion (1900–1910, Heinrich Renard ), the Auguste Viktoria Hospital on the Mount of Olives (1907 –1910, Carl Gause / Robert Leibnitz ) or the Protestant Metzer Stadtkirche (1901–1904, Conrad Wahn ). The Imperial Palace in Posen (1905–1913, Franz Schwechten), the Metz main train station (1905–1908, Jürgen Kröger) and the government building in Koblenz (1902–1905, Paul Kieschke ) can be named among the secular neo-Romanesque buildings initiated by the emperor .

Ludwig Becker's adoption of late Staufer architectural forms can also be assigned a programmatic character.

The richly painted inside the building of the Church of St. Joseph in Montigny consists of Jaumont Stone , the local light yellow colored sandstone and not from gray-red Vosges -Sandstein as the other imperial funded public buildings of that time in Metz and the surrounding area. The nave in the three-aisled basilica style is four-bay and vaulted with ribs. The transept unloads with two bays and just closes. The crossing is vaulted with an octagonal dome on trumpets , which is decorated with a blind gallery on the outside. The cloister vaults of the crossing of Limburg Cathedral or of St. Quirinus in Neuss can be named as historical models of the elaborate crossing design . The basic cubature of the Quirinus Minster may also have been the source of inspiration for the tower facade in Montigny. The choir part closes in three apses.

Furnishing

Mural

The interior of the Josephskirche in Montigny is adorned with a multitude of wall paintings, which are divided into five main groups:

- in the nave: large groups of ornaments with floral patterns, inscriptions and mythical creatures ; the representation of holy cities (including Bethlehem , Jerusalem and Rome ) in the vault centers

- in the aisles: floral ornamental paintings

- in the dome: paradise with the four paradise rivers Pishon, Gihon , Tigris and Euphrates ( Gen 2.10–14 EU ).

- in the transept: ornamental fields with mythical creatures

- in the apse: Christ as Pantocrator on the throne of the Last Judgment with the book of life as well as a lily and a double-edged sword surrounded by two adoring angels; Four other angels hold Jesus' instruments of passion (vinegar sponge, lance , scourge , cross , crucifixion nails , hammer); The heavenly coronation of St. Joseph and St. Privatus von Mende (parish patron of the previous church) by angels and the representation of planets, sun, moon and stars; Lions are depicted on the wall surfaces.

- Triumphal arch: The depiction of the apocalyptic Agnus Dei with the Latin inscription “Dignus es (sic!) Agnus accipere honorem et gloriam” (German translation: “The Lamb is worthy to receive honor and glory”; Rev 5.12 EU ); It stands for 'es' instead of 'est'.

All wall paintings were extensively restored between 2008 and 2011.

window

With regard to the windows, the historic neo-Romanesque glazing from the Wiesbaden company Martin has been preserved. The apse windows thematize the seven sacraments . The transept windows show scenes from the life of the church patron, St. Joseph, as well as from the life of Mary . Representations of various saints adorn the glazing of the nave and the narthex. The windows of the upper aisle and the small apses are glazed using the grisaille technique.

High altar

The high altar, a foundation of a parishioner, is designed in the form of Romanesque reliquary shrines. It was created in the Colmar workshop by Theophil Klem (1849–1923). The figurative and ornamental works are all based on Maasland Romanesque art. A representation of the Trinity is attached above the exposure niche . Below is the tabernacle with a representation of Agnus Dei . The wooden altarpiece , standing on marble pillars, contains a relief representation of six saints. Saint Louis , King of France, Saint Clement of Metz , the first Bishop of Metz, John the Baptist , Saint Martin of Tours , Saint Nicholas of Myra, the patron saint of Lorraine and Saint Thomas Aquinas are shown .

The three-part stipes of the altar show, using mosaic technique, Old Testament prefigurations of the sacrificial death of Jesus Christ and the Eucharist : (from left to right) the sacrifice of Melchizedek , the salvation of the Israelites through the sight of the brazen serpent and the appearance of God above Abel's incense altar .

The predella above the cafeteria contains the Latin inscription from the step prayer "Introibo ad altare Dei, ad Deum qui laetificat iuventutem meam."

The reliquary grave of the high altar contains relics of the holy Metz martyr Livarius von Marsal as well as the two holy Trier martyrs of the Thebaic Legion , Severinus and Theodor.

The altar stands under an elaborate canopy on pillars of four bundles of greenish Carrara marble . The corners of the roof structure are decorated with depictions of angels on thrones. You are holding banderoles in your hands. The front eyelash shows the Virgin Mary venerated by angels . The interior of the canopy vaults thematize the birth of Jesus , the miraculous and wonderful multiplication of bread , the crucifixion and the resurrection of Jesus. The roof structure of the canopy is crowned by a lantern with a Lorraine cross at its top .

To the left of the altar on the wall is the cornerstone of the church.

Celebration altar

The popular altar erected in the wake of the Second Vatican Council in 1983 was designed by Claude Michel under theological and liturgical advice of Théo Louis. André Forfert was responsible for the execution. The stipes is decorated with a relief of the face of Jesus Christ. The four supporting columns and the symbol sculptures of the four evangelists at the corners come from the earlier sideboard.

The reliquary grave in the altar contains relics of St. Therese of Lisieux , St. Metz Bishop Sigebald and St. Eustachius, the martyr .

Left choir flank chapel

The St. Mary's altar is located in the left choir flank chapel. It was donated by the Montigny parishioner Marie-Léontine de Nettancourt, Duchess of Clermont-Tonnerre. The wings of the retable altar thematize the life of Mary ( Annunciation of the Lord , Visitation of the Virgin , Birth of Christ and the presentation of the Lord in the temple). On the back of the wing panels there are floral ornaments. The center of the altar contains a statue of the Virgin Mary with the baby Jesus, a colored stone sculpture from the 16th century, which previously adorned the portal of the old church of St. Anthony of Padua. Two small adoring angels float around the head of Mary.

The frescoes of the apse calotte quote the invocations of Mary from the Lauretanian litany with symbolic images and tapes in Latin : "Rosa mystica" (mystical rose), "Domus aurea" (golden house), "Foederis arca" ( ark of the covenant ), "Ianua coeli" ( Gate of Heaven ) and “Stella matutina” ( morning star ).

Right choir flank chapel

The Sacred Heart Altar stands in the right choir flank chapel next to the sacristy . Like all altars in the Josephskirche, this altar is also designed in the forms of Maasland Romanesque art. The richly ornamented and stone-set altar is a foundation of the female members of the Siechler family from Montigny. The center of the reredos is a statue of Jesus Christ in a flame mandorla with a visible heart on the chest as a sign of divine love for people. In the spandrels of the mandorla, two adoring angels are depicted at the top and a man and a woman in medieval garb praying at the bottom. The Latin inscription of the halo is: “Venite ad me omnes qui laboratis et onerati estis et ego reficiam vos.” (German translation: “Come to me, all of you who struggle and have to bear heavy burdens. I will refresh you. "; Mt 11.28 EU )

The two wings of the retable show Saint Margaret Maria Alacoque on the left and Pope Pius X on the right with his papal coat of arms and his motto “Instaurare omnia in Christo” (German translation: “Renew everything in Christ”) in knee-kneeling veneration of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. On the back there are angels with quotations from the litany of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Latin: “Cor Jesu, fons totius consolationis, miserere nobis. Cor Jesu, bonitate et amore plenum, miserere nobis "(German translation:" O heart of Jesus, source of all consolation, have mercy on us. O heart of Jesus, full of goodness and love, have mercy on us. ")

The present wall paintings of Apsiskalotte show in God's vision of the Prophet Ezekiel described four worshipers before the throne of God ( Ezek 1.4 to 28 EU ), which is also the author of the New Testament apocalypse were taken ( Rev 4,6-8 EU ). From left to right these are: a winged lion , a winged human being, an eagle and a winged bull . All four beings each carry a book. A lettering band hovers over each of the four beings (from left to right: S. Marcus, S. Mathäus, S. Johannes, S. Lucas). The gaze of her nimbly head is on Jesus Christ. According to the testimony of the Bible, the heavenly beings depicted proclaim the holiness of God. In Christian theology they are associated with the four evangelists John , Luke , Mark and Matthew . The human-faced being stands for the incarnation of Jesus, the bull-faced being for his sacrificial death, the lion-faced being for the resurrection and the eagle-faced being for Jesus' return to the Father. A menorah, flanked by incense burners , is depicted between the beings in an arched field .

St. Anthony altar

The Antonius altar is set up in a side chapel in the left transept. Saint Anthony of Padua is the third patron saint of the church, alongside Saint Joseph and Saint Privatus. The patronage of the altar commemorates the patron saint of the old monastery church of Montigny. The central statue of St. Anthony with the baby Jesus in his arms is flanked by a statue of St. Francis of Assisi (left) and a statue of St. Clare of Assisi (right)

On the wall to the left of the altar next to the choir organ is a copy of the painting "L'adoration des Bergers" (Adoration of the Shepherds) by Jusepe de Ribera , the original of which is in the Louvre in Paris .

St. Private Altar

The private altar is located in a side chapel in the right transept. It was donated by the builder of the Joseph Church, Pastor Philipp Châtelain. The patronage of the altar commemorates the patron saint of the old parish church of Montigny. Holy Privatus can be seen in the central niche of the reredos. The polychrome stone statue dates from the 15th century and was restored at the beginning of the 20th century. Before, this statue stood in the niche of a house on Rue Guynemer. On the left side of the reredos an angel has sunk in worship of the holy martyr. On the right, Pastor Philipp Châtelain is shown offering the model of the new St. Joseph's Church to the holy private.

Sacred objects

- Statues

In addition to the numerous neo-Romanesque statues in the Josephskirche in Montigny, there are also historical pieces from the previous church of today's neo-Romanesque sacred building, including a wooden figure of Christ from the 15th century and a statue of St. Privatus von Mende .

- Way of the Cross

The Way of the Cross of the Josephskirche consists of fourteen stations carved in stone, which were created by the sculptor Anton Mormann ( Wiedenbrücker Schule ). Mormann had also made the station of the cross in the Herz-Jesu-Kirche in Koblenz. The stations of the cross in Montigny are arranged along the right inner wall of the Josephskirche and the last three - the death of Jesus, the removal from the cross and the burial of Jesus - are in the narthex of the church. The neo-Romanesque Way of the Cross was consecrated on Good Friday, April 14, 1911, by Nicolas Hamant, head of the small seminary, on behalf of the Bishop of Metz.

- Mission cross

The large mission cross from 1947 is in the right transept. It had stood on the square in front of the Josephskirche from 1947 to 1949. When the statue of St. Joan of Arc was erected in its place in 1949, the mission cross was transferred to the church.

- Jeanne d'Arc monument

The first statue of the Lorraine saint Joan of Arc was inaugurated on May 30, 1935 by Mayor Félix Peupion and Bishop Jean-Baptiste Pelt . Peupion died during the Nazi deportation, the square behind the Josephskirche was named in his honor after the Second World War . The statue of the French national saint was a replica of the sculpture "Jeanne after the victory" by the sculptor Henri Allouard . During the Nazi occupation, the Jeanne d'Arc monument was destroyed by the Nazi rulers. Only the sword could be recovered by a parishioner. In 1949, the monument was reconstructed, supplemented with the sword of the previous statue and inaugurated as part of a solemn ceremony by the Vicar General of the Diocese of Metz, Louis, in the presence of the then French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman . Schuman, who campaigned for reconciliation with Germany and German-French friendship and is considered the founding father of the European Union , stated in his speech at the time that Jeanne d'Arc had made a decisive contribution to establishing Christianity as the foundation of Europe promote.

- Atonement Cross

The Atonement Cross (Croix du sacrilège), which is now behind the St. Joseph's Church, originally stood in front of the Protestant church under the imperial oak . Since the cross supposedly obstructed access to this church, it was moved to its present location in 1915. It was built by the Montigny citizen Blaise Fabert in honor of the Blessed Sacrament. The name "Croix du sacrilège" ( Sacrilege Cross) reminds us that thieves stole the chalices from St. Anthony's Church in Montigny on January 22nd, 1804 and poured out the consecrated hosts on the ground where it was previously installed.

Organs

The current main organ on the entrance gallery was built in 1987 by François Delangue ( Amanvillers ) and blessed by Bishop Pierre Raffin during an inauguration ceremony . The instrument has 34 registers that can be played using three manuals . The pipes are made of pewter and wood. The action mechanism is mechanical, the stop action is electric. In 1991 the main organ was supplemented with an echo work. The organ was completely restored in 2005 by Jean-Louis Helleringer. The predecessor instrument of this main organ was an instrument from 1950.

The choir organ in the left transept was built in 1905 by the Cavaillé-Coll company and electrified by Jacquot Lavergne in 1939. Several maintenance work has been carried out since then, the last one in 2005. The choir organ can be operated from the main organ manuals.

Bells

The first bells of the new Josephskirche were cast by the Otto bell foundry in Hemelingen and were blessed by Bishop Willibrord Benzler on June 30, 1907:

- Marienglocke, 4568 kg

- Saint Concordia , 1895 kg

- Holy Privatus, 1323 kg

- Saint Joseph, 929 kg

- Saint Mary Magdalene , 779 kg

- Saint Martha , 559 kg

- Saint Lucia , 390 kg

In 1917 the three smaller bells had to be handed over to the German military administration and were melted down for war material. It was not until 1931 that three new bells could be purchased from the Alsatian bell foundry Causard in Colmar , which were consecrated by Bishop Jean-Baptiste Pelt on September 28, 1931 :

- Saint Marguerite-Marie , 779 kg

- Holy Honorine , 562 kg

- Saint Joan of Arc , 385 kg

The disposition of the current seven-part bell in the bell tower is: a ° -d′-e′-fis′-g′-a′-h ′.

Pastor

The following clergy worked in Montigny:

- Nicolas Pichon: 1790 to 1829; Due to the anti-religious measures of the French Revolution , Nicolas Pichon was suspended because he refused to take the oath on the constitution . He was represented by the following priests until 1793:

- Pierre Lucot: 1791 to 1792

- Father Georges: 1792 to 1793

- (?)

- Philipp (e) Châtelain: 1899 to 1922; Builder of the Josephskirche and the rectory ; * February 27, 1863 in the hamlet of Hallingen / Halling in the town of Püttlingen , † January 9, 1922 in Montigny-lès-Metz; During the First World War he was exiled to Silesia by the German authorities from 1914 to 1918 because of pro-French tendencies . Châtelain was buried in the Josephskirche in 1922.

- Léon Zimmermann: 1922 to 1950; * March 9, 1884 in St. Avold , consecrated on July 19, 1908 in Metz, expulsion by the German authorities during the Nazi annexation ; since October 2, 1950 dean of the cathedral chapter of Metz; † May 29, 1962 in Metz

- Marcel Leroy: 1950 to 1967; * March 7, 1900 in Flavigny-sur-Moselle , consecrated in Metz on July 15, 1928, expulsion by the German authorities during the Nazi annexation; † June 28, 1981 in Metz

- (?)

literature

- The inauguration of the new Catholic parish church in Montigny. In: Metzer Zeitung, July 31, 1906.

- New church in Montigny. In: Metzer Zeitung, July 29, 1906.

- Niels Wilcken: Architecture in the Border Area. Public construction in Alsace-Lorraine (1871–1918). Saarbrücken 2000, pp. 273-275.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Folz, above surname: Metz as the German district capital (1870–1913). In: A. Ruppel (Ed.): Lothringen and his capital. A collection of orienting essays. Metz 1913, pp. 372-383.

- ^ Thomas Nipperdey: German history. 1866-1918. Volume 2: Power state before democracy. Beck, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-406-34801-7 , p. 72.

- ↑ Rolf Wittenbrock: The city expansion of Metz (1898-1903). National interests and areas of conflict in a fortified town near the border. In: Francia, 18/3 (1991), pp. 1-23.

- ↑ Christiane Pignong-Feller: Metz 1900–1939. An imperial architecture for a new city. German Transfer from Margarete Ruck-Vinson (Èditions du patrimoine, Center des monuments nationaux), Paris 2014.

- ↑ http://www.montigny-les-metz.fr/l-eglise-saint-joseph , accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ https://metz.catholique.fr/sites-paroissiaux/saint-privat/saint-joseph/ , accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ http://www.montigny-les-metz.fr/l-eglise-saint-joseph , accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ Marcel Grosdidier de Matons: Nouveau guide de Metz, Metz 1936.

- ^ New church building in Montigny, in: Metzer Zeitung, June 29, 1906.

- ↑ Kristine Marschall: Sacred buildings of classicism and historicism in Saarland. (= Publications by the Institute for Regional Studies in Saarland, Volume 40), Saarbrücken 2002, p. 84.

- ^ The inauguration of the new Catholic parish church in Montigny, in: Metzer Zeitung, July 31, 1906.

- ^ Niels Wilcken: Architecture in the border area, The public building industry in Alsace-Lorraine (1871-1918), Saarbrücken 2000, pp. 273-275.

- ^ Niels Wilcken: Architecture in the border area, The public building industry in Alsace-Lorraine (1871-1918), Saarbrücken 2000, pp. 273-275.

- ^ Niels Wilcken: Vom Drachen Graully to the Center Pompidou-Metz, Metz, a culture guide, Merzig 2011, p. 216.

- ↑ Paul Seidel (Ed.): Der Kaiser und die Kunst, Berlin 1907, p. 78.

- ^ Udo Liessem: Die Herz-Jesu-Kirche in Koblenz (Große Baudenkmäler, Issue 317), 3rd, modified edition, Munich, Berlin 1998, pp. 6-8.

- ↑ Kristine Marschall: Sacred buildings of classicism and historicism in Saarland. (= Publications by the Institute for Regional Studies in Saarland, Volume 40), Saarbrücken 2002, pp. 84–85, 122.

- ↑ http://www.montigny-les-metz.fr/l-eglise-saint-joseph , accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ http://www.montigny-les-metz.fr/l-eglise-saint-joseph , accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ https://metz.catholique.fr/sites-paroissiaux/saint-privat/saint-joseph/ , accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ https://metz.catholique.fr/sites-paroissiaux/saint-privat/saint-joseph/ , accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ https://metz.catholique.fr/sites-paroissiaux/saint-privat/saint-joseph/ , accessed on March 22, 2020.

- ↑ https://metz.catholique.fr/sites-paroissiaux/saint-privat/saint-joseph/ , accessed on March 22, 2020.

- ↑ Géza Jászai: Evangelist or God's symbols ?, On the iconology of the Maiestas Domini representation of the Carolingian Vivian Bible, in: Das Münster, Zeitschrift für Christian Kunst und Kunstwissenschaft, 1, 2019, 72nd year, Regensburg 2019, p 25-29.

- ↑ https://metz.catholique.fr/sites-paroissiaux/saint-privat/saint-joseph/ , accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ https://metz.catholique.fr/sites-paroissiaux/saint-privat/saint-joseph/ , accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ http://www.montigny-les-metz.fr/l-eglise-saint-joseph , accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ https://metz.catholique.fr/sites-paroissiaux/saint-privat/saint-joseph/ , accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ http://www.montigny-les-metz.fr/l-eglise-saint-joseph , accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ https://metz.catholique.fr/sites-paroissiaux/saint-privat/saint-joseph/ , accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XpdtH7exw20 , accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ https://metz.catholique.fr/sites-paroissiaux/saint-privat/saint-joseph/ , accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ https://metz.catholique.fr/sites-paroissiaux/saint-privat/saint-joseph/ , accessed on March 22, 2020.

Coordinates: 49 ° 6 ′ 1.7 ″ N , 6 ° 9 ′ 22 ″ E