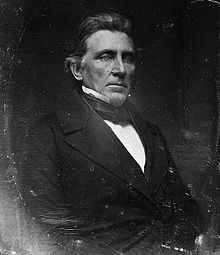

William M. Gwin

William McKendree Gwin (born October 9, 1805 in Gallatin , Tennessee , † September 3, 1885 in New York City ) was an American doctor and politician ( Democratic Party ). Gwin was a member of the US House of Representatives for Mississippi . He was also one of the first two US Senators for California along with John C. Frémont . Before, during, and after the Civil War , Gwin was known in California, Washington, and the southern states as a sympathizer of the South.

Early life

Gwin was the son of Reverend James Gwin, a Methodist priest who worked under William McKendree . McKendree was the first Native American Methodist priest and became the namesake of young Gwin. Reverend Gwin had served in the military under General Andrew Jackson . William Gwin studied medicine at Transylvania University in Lexington , where he graduated in 1828.

Political career

Gwin practiced as a doctor in Clinton, Mississippi until 1833. In that year he was United States Marshal for Mississippi for one year .

In 1840 he was elected to the US House of Representatives as a Mississippi MP . He turned down another nomination in 1842 due to financial exposure. When James K. Polk took over the office of US President , he entrusted Gwin with the supervision of the construction of the new customs house in New Orleans . In 1849 he moved to California. Also in 1849 he took part in the Constitutional Convention of California. He bought land in Paloma , where he built a gold mine. The Gwin mine made him a fortune. Gwin also founded the Democrats' Chivalry wing, which stood opposite the Whig wing.

After California was accepted as a US state , Gwin was elected US Senator . His tenure lasted from September 9, 1850 to March 3, 1855. Gwin campaigned strongly for the expansion of the states on the Pacific and in 1852 campaigned for an exploration of the Bering Strait . As a result of the California gold rush of 1848 , Gwin tabled a bill that was passed on March 3, 1851. This called a three-member Public Land Commission into being, which should determine the legality of Spanish and Mexican land donations in California. From 1851 to 1855 he was chairman of the US Senate Committee on Naval Affairs .

The California Governor John Bigler turned to Gwin's rival David C. Broderick , rejected as Gwin him in gaining the ambassador post in Chile to help. Broderick was named chairman of the California Democrats, whereupon they split up. Gwin dueled with Joseph W. McCorkle . The 30-yard rifle duel took place over a dispute over alleged mismanagement of Gwin's state resources. This was the beginning of a time of chaos in California politics, marked by bribery, intimidation and political maneuvers. Although Broderick's supporters were nominally weaker, they were able to prevent Gwin's re-election in 1854. However, when the Know-Nothing Party began to exploit the weakness of the Democrats, Broderick accepted Gwin's new candidacy in 1856, after which he was re-elected and from January 13, 1857 to March 2, 1861 went to Washington again. He took Joseph Heco with him to introduce him to his friend, US President James Buchanan .

During his second term, Gwin sat on the Senate Finance Committee . He achieved successes such as the establishment of the California Mint and a naval base with shipyard, the development of the Pacific coast and a law to build a steamship line between San Francisco , China and Japan , across the Sandwich Islands . From 1860 he campaigned for the purchase of Alaska from the Russian Tsar. Although the reorganized Republicans achieved some major successes in California, Gwin's wing of the Democrats was also very successful in the 1859 election. After Abraham Lincoln was elected President in 1860, Gwin helped organize secret talks between Lincoln's Secretary of State, William H. Seward, and Southern leaders. These talks should prevent the breakup of the Union. Before hostilities broke out between the states, Gwin toured the south and his chivalry spoke out in favor of the south. Gwin also explored the possibility of detaching a California-led Pacific republic from the Union; however, after the poor performance of the Democrats in 1861, there was no longer any political leeway.

Next life

Gwin returned to New York. He traveled on the same ship as Edwin Vose Sumner (Commander of the Pacific Division of Union Forces) and Michail Bakunin - an acquaintance of Joseph Heco. Sumner arranged for Gwin to be arrested as a secessionist sympathizer, but Abraham Lincoln advocated his release. Gwin sent his wife and one of his daughters to Europe and returned to a plantation in Mississippi himself. After the plantation was destroyed in the war, Gwin fled to Paris with another daughter and son. In 1864 he tried Napoleon III. convince American slave owners to settle in Sonora , Mexico . Despite initial interest, Napoleon declined, as his protégé, Maximilian I , feared that the southerners could take over Sonora entirely. After the war, Gwin returned to the United States and surrendered to General Philip Sheridan in New Orleans . General Sheridan granted his release so that he could return to his family, who had also returned, but was overruled by President Andrew Johnson , with whom he was at war with.

Gwin retired as a farmer in California, but died in New York City in 1885 . He was buried in Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland .

Individual evidence

- ^ WW Robinson: Land in California. University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles, CA 1948, p. 100.

literature

- Arthur Quinn: The Rivals: William Gwin, David Broderick, and the Birth of California . Crown Publishers: The Library of the American West, New York 1994.

- WW Robinson: Land in California . University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles, CA 1948.

Web links

- William M. Gwin in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress (English)

- William M. Gwin in the database of Find a Grave (English)

- Guide to the William McKendree Gwin Papers at The Bancroft Library

- Howard A. DeWitt: Senator William Gwin and the Politics of Prejudice.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gwin, William M. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gwin, William McKendree (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American politician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 9, 1805 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Gallatin , Tennessee |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 3, 1885 |

| Place of death | New York City |