Second Kamchatka expedition

The Second Kamchatka Expedition , also known as the Great Nordic Expedition , was a research and discovery voyage conducted between 1733 and 1743 under the direction of the naval officer Vitus Bering , whose participants explored Siberia , measured the northern coasts of the Russian Empire and sea routes from Okhotsk to North America and East Siberia Explored Japan .

The results of the expedition, which were achieved with considerable hardship, include the discovery of Alaska , the Aleutian Islands and the commanders' islands , the precise mapping of the northern and northeastern coasts of Russia and the Kuril Islands , the refutation of the legend of the existence of fabulous countries in the North Pacific and the ethnographic one , historical and scientific exploration of Siberia and Kamchatka . With the failure of a circumnavigation of the northeastern tip of Asia by sea, the desire for an economic use of the northeast passage , which had been cherished since the beginning of the 16th century, was shattered .

With over 3000 people directly and indirectly involved, the Second Kamchatka Expedition was one of the largest expedition projects in history. The total cost of the company, which was financed by the Russian state, was an estimated 1.5 million rubles , unimaginably high for the time , which was roughly one sixth of Russia's income in 1724.

prehistory

Foundation of the Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg

The beginning of the systematic geographic exploration and scientific exploration of the eastern part of Asia in the 18th century goes back to the initiative of Tsar Peter I (1672-1725), who ruled Russia from 1689 . He was encouraged to create his own academy of sciences on his study trip through various European countries in 1697 and 1698. In the years 1723/24 this plan took shape. In order to gain access to the rest of Europe in the scientific field and to put the training of his own specialists on a permanent basis, Peter decided to call foreign scholars to Russia and to create his own Russian academy in Saint Petersburg .

In December 1725 this facility was officially opened. Young, mostly German-speaking scientists formed the core of the academy's staff in the first decade after it was founded. One of her tasks was to organize and provide scientific support for expeditions to previously unknown parts of the Russian Empire.

First expeditions to Siberia

Tsar Peter had met Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) several times during his life and was confronted by him at their last meeting in Bad Pyrmont in 1716 with the question of whether there was a land connection between the northeastern tip of Asia and North America. This question was of considerable relevance against the background of the discussion about the origin of mankind. If one did not want to give up the belief in the common origin of all human beings, then in the event that Asia and North America were not connected with one another, the question arises as to which way humans had come to the New World . In order to obtain final certainty about the existence of a land connection between the two continents, Peter sent the two Russian geodesists Ivan Jewreinow (1694-1724) and Fyodor Luschin (1695-1727) to the eastern edge of his empire in 1719 . However, their expedition was unsuccessful, at least in terms of answering the question about the land connection.

Between 1720 and 1727, the German physician Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt (1685–1735) traveled to western and central Siberia and carried out studies on geography, mineralogy, botany and zoology. He also collected observations in the fields of philology, ethnography, economics and trade. Today Messerschmidt's expedition is the prelude to the scientific exploration of Siberia.

The First Kamchatka Expedition

Since Yevreinov and Luschin's expedition had not clarified the question of the land connection between Asia and America, Peter the Great signed the order for another large expedition to the east in 1724.

The first Kamchatka expedition lasted from 1728 to 1730. The company was led by the Danish captain Vitus Jonassen Bering (1681–1741), who had served as a naval officer in the Imperial Russian fleet since 1704. With his ship St. Gabriel , built at the mouth of the Kamchatka River , Bering set out in a northeasterly direction in 1728 and reached a point at a north latitude of 67 degrees where the coast did not extend further north. However, due to the poor weather conditions, he was unable to sight the North American mainland. Despite the new knowledge about the geography of the north-eastern coast of Siberia, the expedition report prepared by Bering after his return was controversial. Since the answer to the question about the exact location of North America was still pending, Bering himself suggested another research trip, the "Second Kamchatka Expedition".

Planning and preparations for the second Kamchatka expedition

The goals of the expedition

At the center of Bering's new expedition plans were the surveying of the northern coasts of the Russian Empire, the expansion of the port of Okhotsk as access to the Pacific Ocean , the search for sea routes to North America and Japan, the development of the Siberian mineral resources and finally the safeguarding of Russian rule eastern part of Asia. The framework conditions for this gigantic project turned out to be extremely favorable.

The tsarina Anna Ivanovna (1693–1740), who ruled from 1730 , endeavored to continue the work of Peter the Great and to advance the territorial and economic expansion of her empire. With the ukase of April 28, 1732, the Tsarina issued a decree to send out a new expedition, which was followed on May 13 and 26, 1732 by two ukasses from the Russian Senate to the Admiralty College to prepare the enterprise and to appoint Vitus Bering as its leader . An ukase from the Senate of June 23, 1732 required the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences to write instructions for the scientific part of the trip. Another ukase from the Senate to Bering of January 7, 1733, finally concerned the organization and tasks of the expedition.

To achieve its goals, the expedition was divided into three groups, each with one or more departments.

The northern group

The task of the northern group was to survey and map the northern coast of Russia between the Arkhangelsk port on the White Sea and the Anadyr River in eastern Siberia. The fulfillment of this task provided the basis for answering the question about the Northeast Passage as a connection between Europe and the Pacific and aimed at finding an alternative to the expensive land transport in Russian China trade and a northern sea route to India.

The Pacific Group

The expedition's Pacific group consisted of two divisions. The first, by Vitus Bering self-directed department should, of Okhotsk off the Kamchatka explore and then go in search of the legendary "João da Gama-Land" (also called "Compagnie Land"). This was named after the Portuguese navigator João da Gama (* around 1540, † after 1591), who claimed in 1589 to have discovered land north of Japan. From "João-da-Gama-Land", Bering's group was then to advance further east to the coast of North America. The second Pacific division was under the direction of the Danish captain Martin Spangberg (d. 1757 or 1761), who had already stood by Bering on the first Kamchatka expedition and was given the task of exploring the sea routes to Japan and China from Okhotsk.

The academic group

The academic department of the expedition was headed by three professors from the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences . The Academy appointed the Württemberg natural scientist and botanist Johann Georg Gmelin (1709–1755) to research the flora and fauna as well as the natural resources of the areas visited . Gmelin had studied in Tübingen and received her doctorate for a thesis on the chemical composition of medicinal water. At the urging of his former academic teacher Georg Bernhard Bilfinger (1693–1750), Gmelin followed this to Russia in 1727. There he received a chair in chemistry and natural history in 1731.

The academy selected the German historian and geographer Gerhard Friedrich Müller (1705–1783) to conduct ethnological and historical studies . Müller had studied in Rinteln and Leipzig and came to Saint Petersburg in 1725 through a friend from university. In 1730 he was appointed associate professor of history at the university there and the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences a year later . From his intensive preoccupation with Russian history, the first volume of the collection of Russian history emerged in 1732 . Due to his arrogant behavior as the office's secretary, Müller got into an argument with other academy members. Therefore, his participation in the expedition was based not only on the desire to have direct access to the historical sources on the trip, but also on gaining distance from Saint Petersburg.

At the suggestion of the astronomer Joseph Nicolas Delisle (1688–1768), who was still appointed to Saint Petersburg by Peter the Great, the Academy of Sciences entrusted his younger brother Louis De l'Isle de la Croyère (1690–1741) with astronomical-geographic and physical measurements. Louis initially served the academy as an adjunct in astronomy. In 1727 the academy management appointed him professor and sent him on a three-year survey trip to Arkhangelsk and the Kola Peninsula , so that he had already gained expedition experience before the trip to Siberia began. Still, Croyère was one of the most controversial participants in the academic department because his skills were later heavily questioned by both Gmelin and Müller.

The participants in the academic group were the only ones not under Bering's command, but the St. Petersburg Academy. Each of the professors received precise instructions about the research program to be completed. The instructions for Croyère and the geodesists accompanying him were written by his brother Joseph Nicolas. Gmelin wrote the instructions for his natural history research himself. He received additional instructions from the anatomist Johann Georg Duvernois (1691–1759), who, like Georg Bernhard Bilfinger, was one of his former academic teachers in Tübingen. Among other things, Duvernois wanted to know whether the people in Siberia could move their ears, whether their uvula were simple, split or three-sided, or whether the Siberian men also had milk in their breasts. The physicist Daniel Bernoulli (1700–1782) wrote instructions for Croyère and Gmelin for carrying out a series of physical measurements. The historian Müller drew up his work plan himself. His main goals were to research the history of all cities visited during the expedition and to collect as many language samples as possible from Siberian ethnic groups with whom he would meet. The two painters Johann Christian Berckhan (died 1751) and Johann Wilhelm Lürsenius (died after 1770), who belonged to the academic department, received special instructions. The academy also instructed the researchers to prepare reports in Russian and Latin on the status and results of the expedition. Numerous astronomical, geodetic and physical measuring instruments were made available to the participants in the academic department to carry out their work. The Siberian governor and governors were required to give the researchers all necessary assistance.

The travels of the three expedition groups (1733–1743)

The academic group

After the two Pacific departments under Martin Spangberg and Vitus Bering had already left Saint Petersburg for the east in February and April 1733, the academic group set out on August 19, 1733. In addition to the three academicians Gmelin , Müller and Croyère , the academic group included the Russian students Stepan Krasheninnikov , Alexei Grolanow, Luka Ivanov, Vasily Tretyakov and Fyodor Popov, the student and translator Ilya Jaontov (d. 1739), the geodesists Andrei Krassilnikow (1705 –1773), Moisei Uschakow (d. Before 1743), Nikifor Tschekin and Alexandr Iwanow (d. 1738), the instrument maker Stepan Ovsjanikow (d. 1738) and the painters Johann Christian Berckhan and Johann Wilhelm Lürsenius. Twelve soldiers, a corporal and a drummer were assigned to protect them. Horses served as a means of transport on land; barges were used on the rivers.

The academic department first traveled through Novgorod , Kazan , Yekaterinburg and Tyumen to Tobolsk , where they arrived in February 1734. In May, Gmelin and Müller separated from the rest of the group to which under the direction Croyères was made, and traveled to December 1734 the Irtysh upwards over Semipalatinsk , Kuznetsk to Tomsk and then to Yeniseisk . They reached Irkutsk in March 1735 via Krasnoyarsk and Udinsk . There they left some of their luggage behind and set out to explore the area around Lake Baikal . They studied the trade in the Russian-Chinese border town of Kyakhta in Transbaikalia and paid a visit to the mines of Argun . They spent the winter in Irkutsk again. Müller looked through and copied documents in the local archive, and Gmelin studied the plants that were collected in the summer.

The next travel destination was Yakutsk , where the participants of the academic department would meet Bering and travel together to Kamchatka . After leaving Irkutsk, the two scholars first traveled along the icy Angara River to Ilimsk , where they celebrated Easter. When the Lena was free of ice in May, they continued their journey downstream by boat and reached Yakutsk in September 1736. Almost all members of the two Pacific departments had now gathered here, and so Gmelin and Müller had great problems finding accommodation at all. To make matters worse, fire broke out in Gmelin's accommodation on November 19, 1736. In his travel memories, which he wrote later, he described the nocturnal situation:

“At nine o'clock a storm was heard and it was said that the fire had broken out; soon afterwards it was said that the house I lived in was on fire. We all hurried; but all help was in vain [...] Who could be more dismayed than I? because at one time I saw myself deprived of all aids to future perceptions, especially the books and instruments, of all my previously prepared essays "

Only a few books and Gmelin's cash could be saved from the burned-out house; some of the coins had melted from the heat. The loss of the botanical scripts hit Gmelin particularly hard. Immediately after the fire, he wrote to the Senate in St. Petersburg asking for replacements for the lost books and scientific instruments.

According to their instructions, the members of the academic group should leave Yakutsk directly for Kamchatka . However, when they learned from Bering that the provisions they needed on Kamchatka had not yet arrived, they decided to first send the student Stepan Krasheninnikov ahead of them. He was commissioned to provide suitable quarters in Bolscherezk, the southernmost place on the peninsula, and then to create a botanical garden with native wild herbs in order to facilitate Gmelin's later work. Gmelin and Müller gave the student an extensive work program for the exploration of Kamchatka. Krasheninnikov should

“... start with the perception of the weather, diligently record the ebb and flow of the Kamchatk sea, the fire-spitting mountain and the warm countries, fish, quadruped and both, animals living in the water and on the land, birds, even everything the sea casts, diligently collects and describes and all news that could be received from Kamchadals, Korjaks and Kurils, both with regard to their way of life, clothing, idolatry, manners and customs, trade and change, as well as their stories of their descent through bring together safe customers and describe them as precisely as possible. "

After all, Gmelin justified the decision in his travel report, enough time had already passed and neither Müller nor he had any particular desire to “become an eternal citizen of Siberia”.

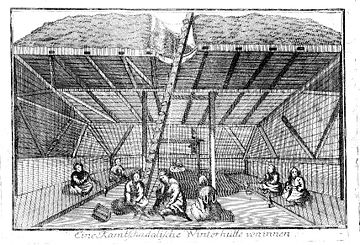

On July 20, 1737 Krasheninnikov left together with the expedition members of the Pacific Department under the leadership of Vitus Bering to Okhotsk . On the subsequent voyage across the Sea of Okhotsk , Krasheninnikov only narrowly escaped death when the ship Fortuna sank and lost his supplies and luggage. As a makeshift he set up in Bolscherezk, the then trading center of Kamchatka on the west coast of the peninsula, and for the next four years explored the fauna and flora of the peninsula on a total of five routes, drew maps and carried out a large number of scientific studies. At the beginning of October 1740, the doctor and naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller (1709–1746) arrived in Kamchatka. After completing his studies, Steller initially worked as a teacher at the August Hermann Franckes orphanage (today's Francke Foundations ) in Halle . With no prospect of an academic career in Prussia and attracted by news of the Second Kamchatka Expedition, he had entered Russian service and arrived in Saint Petersburg in November 1734. After an expansion of the scientific staff of the expedition had been decided in early 1735, he traveled after the academic department to carry out botanical studies as an assistant to Gmelins. At the beginning of 1739 he met Gmelin and Müller in the Siberian Jenisseisk . In the meantime they had decided not to travel to Kamchatka themselves, and instead sent Steller on the journey to the east. When he finally arrived in Bolscherezk on October 2, 1740, he first found out about Krasheninnikov's previous work on the basis of a detailed written report. Since there was hardly any botanical work to be carried out in the onset of winter, Steller and Krascheninnikow made a detour to a nearby settlement of the local Itelmens , before setting off on a dog sled journey through the south of the peninsula in early 1741. After his return he received a letter from Bering asking him to accompany him as a doctor on the sea expedition to North America. In 1742 Krasheninnikov was also ordered to leave Kamchatka, then met Gmelin and Müller in Siberia and returned to Saint Petersburg with both of them in 1743.

The northern group

The northern group was faced with the task of surveying and mapping the entire coast between Arkhangelsk and today's Bering Strait . The basis for this was the idea, discussed since the 16th century, of the existence of a north-east passage and thus a northern sea trade connection between Europe and China . Such a route through the Arctic Ocean would have been considerably more cost-effective for Russian-Chinese trade than the costly land transport through Central Asia . Peter I had taken up the idea of a search for the Northeast Passage during his reign and commissioned his advisor Fyodor Saltykow (d. 1715) to develop detailed plans for exploring the northern coasts of the Tsarist Empire. The proposals developed by Saltykow in 1713 and 1714 became the basis of the expedition plan for the northern group of the Great Nordic Expedition. This planned to build ships inland on the Ob and on the Lena , which would then sail to the respective estuaries and explore the coast from there. A ship built in Tobolsk am Ob was to sail east from the estuary and meet a ship built on the Lena, which in turn was supposed to sail west. A third ship, also built on the Lena, was commissioned to sail eastwards to Kamchatka . The construction of magazines and signal towers along the coastline was planned for the supply and better orientation of the individual groups.

The fulfillment of their tasks soon turned out to be difficult and costly for the expedition members of the northern group. Dmitri Owzyn needed four attempts alone before he finally reached the mouth of the Yenisei in 1737, coming from the west after the completion of his ship in Tobolsk . A group led by Lieutenant Vasily Prontschishchev (1702–1736) managed to bypass the Taimyr peninsula between Lake Laptev and Lake Kara coming from the east on the second attempt . Both Prontschishchev and his wife accompanying him and a large part of the team lost their lives in this company. Three years later, Captain Khariton Laptev made a new attempt to circumnavigate the Taimyr Peninsula from the east. First he and his team reached the Chatanga Golf , where they found simple accommodation and provisions for wintering. However, when they set off again the next year, their ship was trapped and crushed by the pack ice. After Laptew had initially sent a group led by his helmsman Semjon Tscheljuskin (around 1700 – after 1760) to explore the island on foot, he set out in April 1741 himself accompanied by a sailor and a Yakut guide. During the next few months, Chelyuskin and Laptev crossed the Taimyr Peninsula and surveyed its coastline. Tscheljuskin reached its northernmost point in the spring of 1742, the Cape Tscheljuskin later named after him . In their reports to the St. Petersburg Admiralty College, both later agreed that the sea route around the peninsula was unsuitable for shipping due to the pack ice.

The third ship under the command of Lieutenant Peter Lassenius (also Lassinius , died 1735) was to set off eastwards from the Lena in 1735. However, Lassenius and his crew got stuck in the ice at the mouth of the Lena and tried to hibernate. When an auxiliary expedition arrived in the spring of 1736, 42 of the original 52 expedition participants had already died, including Lassenius. Thereupon Bering sent a new group under the command of Dmitri Laptew (d. After 1762), a cousin of Chariton Laptew , to the northern coast of Siberia. Advancing eastward, Dmitry Laptev reached the Indigirka River in the summer of 1739 before his ship was trapped in the ice. After wintering, Laptew had smaller boats built to be able to maneuver better in the ice, and in this way reached the mouth of the Kolyma River in 1740 . After having to hibernate in the ice again, Laptew finally decided to travel on overland to the mouth of the Anadyr on the southern edge of the Chukchi Peninsula . As a result, it was clear that the difficult climatic conditions did not allow economic use of the Northeast Passage. Nevertheless, the participants in the northern group managed to completely map the northern coasts of Siberia except for the Kola peninsula and the Chukchi peninsula. In contrast, the first conquering of the northeast passage in a west-east direction was only possible at the end of the 19th century, when the Swedish polar explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld advanced through the northern Arctic Ocean to the Bering Strait with his steamer Vega in 1878/79 .

The Pacific Group

Spangberg's trips to Japan

The first Pacific department under the direction of the Danish captain Martin Spangberg (1698? –1761; also: Spanberg ) had been commissioned to explore the sea route to Japan and thus to enable direct trade contact between Japan and the Russian Empire. Spangberg had been in the service of the Russian Navy since 1720 and had accompanied Vitus Bering on the First Kamchatka Expedition between 1728 and 1730 . In 1732 he was designated as a participant in the Second Kamchatka Expedition. In addition to exploring a sea route from Kamchatka to the mouth of the Amur and on to Japan, his task was to find the country "Jesso" (also "Jedso" or "Jeso"), which was believed to be connected to Japan .

After his arrival in Okhotsk , Spangberg had two ships built there between 1734 and 1737. In June 1738 the Brigantine Archangel Michail under the command of Spangberg and the double sloop Nadeshda (Russian for "hope") under Lieutenant William Walton ran south from the port together with St. Gabriel , who was still from the First Kamchatka Expedition under Alexander Scheltinga from Okhotsk. Spangberg soon had to part with the Nadeshda and St. Gabriel due to damage and so he reached the island of Urup , which belongs to the southern group of the Kuril Islands, alone with the Archangel Mikhail , before he decided to return home due to unfavorable weather conditions. He determined the geographical location of 31 other Kuril Islands until he returned to Kamchatka, where he spent the winter.

After building a new ship and repairing the others, Spangberg made another attempt in May 1739. He got caught in a storm that separated the ships. Independently of each other, Walton and Spangberg reached the Japanese island of Honshu in June . It came off the island of Aji on the Oshika peninsula in the former Principality of Sendai , as well as separately in Amazu on the Bōsō peninsula , first contacts with Japanese fishermen and later also for the exchange of goods and gifts. After further exploratory trips, all participants in the Pacific Department under Spangberg returned to Okhotsk via Kamchatka at the end of August 1739. Since Spangberg had successfully completed his task of exploring and mapping the sea route to Japan, Bering sent him back to Saint Petersburg with Walton to report . A comprehensive description of these contacts with Japan can be found in volume three of the collection of Russian history by Gerhard Friedrich Müller , which was apparently modeled on Spangberg's diary.

In Saint Petersburg, however, Spangberg's results were questioned, and so in May 1742 he set off again for Japan with four ships. During this trip, Alexander Scheltinga reached the east coast of the Sakhalin island , which he believed to be the legendary "Jesso". Spangberg himself had to turn back unsuccessfully and traveled back to Saint Petersburg in August 1745 without official orders, which is why he was demoted and placed under arrest until the end of 1747.

Bering's and Tschirikov's trips to America

Eight years after the start of the expedition, Bering was able to tackle one of the company's most important goals, the exploration of the sea route to North America. Under the direction of the Russian shipbuilder Adrei Kuzmin (d. 1744), the construction of two package boats began in 1737 near the Okhota River on the Sea of Okhotsk . The construction of the two ships proceeded only slowly because there were no building materials and difficult weather conditions delayed the work. In the summer of 1739 the canvas arrived in Okhotsk on 40 horses and by the beginning of November 1739 the carpentry work was finished. In June 1740 the two package boats were launched and baptized in the names of the two apostles Peter and Paul . On September 15, 1740, the two ships left Okhotsk and sailed to Bolsheetsk on Kamchatka , where the crews spent the winter.

On June 15, 1741, the flagship St. Peter set sail under the command of Vitus Bering and the St. Paul under the command of Alexei Tschirikow from Petropavlovsk and set a course east-southeast to the legendary "João-da-Gama- Land ”(also“ Compagnieland ”). Louis De l'Isle de la Croyère had presented Bering's officers at a preparatory meeting held in 1741 with a map of his brother showing the location of this legendary country. In fact, the "João-da-Gama-Land" probably meant the Kuril archipelago and so Bering and Tschirikow sailed south without any prospect of success until June 23rd. After the decision was finally made to change course to north-northeast, a storm separated the two ships.

On July 26, the St. Peter's crew sighted land at latitude 58 ° 14 ′ north - it was Alaska . The naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller assigned to Bering wrote in retrospect:

“One had not a little pleasure now that we were under the country, and to listen to the conflicting affects of the high imagination of oneself and future rewards and the pathetic speeches. Some wanted to approach the country at once and seek out the port. Others presented this very dangerous. But everyone acted for himself and no one introduced anything to the captain-commander. The deliberations and commissions that are usually done in the country because of minor matters were now omitted here in the most important business and the main point of the Kamchatk expedition, which lasted ten years, and we saw nothing in common and unity among us except that we were locked up in one vehicle were."

On July 30th, Elias Day named after the biblical prophet Elijah , St. Peter anchored off an island off the coast, now Kayak Island . In the erroneous assumption that they had reached a headland, the landing site was christened “Cape St. Elias”. While the crew replenished the St. Peter's water supplies , Steller was set down on land accompanied by the Cossack Foma Lepichin. He first came across an abandoned fireplace and the remains of a meal and then discovered a storage cellar, in which he found storage containers made of tree bark filled with smoked fish, straps made of plant fibers, arrows and various grasses and herbs. As he explored the island further, he saw smoke rising, but he did not meet people. Then Steller collected plants. A diademed jay , which his companion had shot and which Steller thought he had already seen in a book about the North American flora and fauna, finally convinced him that he had really landed in North America. But Captain Bering, who feared the weather would worsen and had already lost too much time in the search for “Joao da Gama land”, urged to leave again after a short time. Steller later noted bitterly in his travelogue:

“The time which was used here for investigations had an arithmetic relationship with the equipment; It took ten years to prepare for this great end, ten hours were devoted to the matter itself. "

On the morning of July 31st, the St. Peter left the island and sailed along the coast of Alaska for two weeks. In the meantime, the deficiency disease scurvy had broken out on the ship . On September 9 and 10, Bering anchored off a small group of islands to replenish water supplies. The first sailor Nikita Schumagin to die of scurvy was buried there. After him, the archipelago is still called the Shumagin Islands today. On September 14th, 1741 there was also a first encounter with the indigenous people, the Alëuts or Unangan .

On the way back, the St. Peter got into bad weather and violent storms. A large part of the crew and Captain Bering himself were seriously ill with scurvy. In addition, water supplies became scarce. On November 15, 1741, land came into view. Steller wrote:

“How great and extraordinary the joy of everyone at this sight cannot be described. The half-dead crawled out to see this, and everyone thanked God warmly for this great grace. "

When two anchor ropes broke on November 16 and the ship ran aground on a reef, the decision had been made to spend the winter on the coast. Instead of Kamchatka, as initially assumed, the crew of St. Peter landed on an island more than 500 kilometers east of the mainland. Although there was enough food on the island, which was populated by arctic foxes, sea otters and partridges, some of the sick expedition participants, including Vitus Bering, died of unknown causes; More recent studies have shown that scurvy, at least in Bering, probably cannot have been the immediate cause. One day after his death, on December 20, 1741, he was buried on Bering Island, which was later named after him . With the beginning of spring the situation of the stranded, who had survived the winter in earth huts, improved. Steller had herbs rich in vitamins added to the diet and so the scurvy sufferers recovered. A new boat was built from the remains of the St. Peter and in the meantime Steller examined the flora and fauna of the island. After setting off for Kamchatka on August 24, 1742, after a thirteen-day sea voyage, he reached the port of Petropavlovsk together with 45 surviving crew members and his descriptions of the Steller manatee, later named after him, in their luggage .

After the separation of the two ships, Tschirikow sailed on with the St. Paul in a north-easterly direction. He reached North America on July 25, 1741, one day before Bering. On July 27th, he tried to send a dinghy with the helmsman Awram M. Dementjew and ten crewmen ashore near Chichagof Island for an investigation. When the men had not returned after six days, Tschirikow dispatched his boatswain, Sidor Saveliev, with three other crew members in the second dinghy to shore. But even these did not return. The following day there was contact with some indigenous people who approached St. Paul with kayaks . Since Tschirikow had no other dinghy with which he could have clarified the fate of his missing crew members, he decided to leave on August 5th. The fate of the 15 men remained in the dark until today.

The return of Tschirikov's group also became a struggle for survival. The fresh food was running low and the water supply was exhausted. On September 19 the men succeeded in exchanging drinking water for knives at another encounter with some Unangan off the island of Adak . In the course of the further journey, however, they were left with nothing but rainwater. Tschirikow himself became so ill with scurvy that he could no longer go on deck and had to hand over command to his helmsman Ivan Jelagin (d. 1766). Under Jelagin's leadership, the St. Paul finally reached her port of destination Petropavlovsk on Kamchatka in October 1741 . Of the original 75 men, only 51 returned; all the officers except for Tschirikow and Jelagin had died on the way. On October 21, 1741, the day they arrived in Kamchatka, the astronomer Louis De l'Isle de la Croyère also died as a result of his scurvy disease.

A trip undertaken in the next year was largely unsuccessful. Tschirikow, who had moved up as expedition leader after Bering's death, went via Okhotsk to Yakutsk to await further instructions from St. Petersburg. However, the Admiralty College did not respond to his proposal to take another voyage to North America. In September 1743, the second Kamchatka expedition was officially declared over.

The results and their reception by learned Europe

overview

With regard to the overall picture of the expedition results, Folkwart Wendland draws the following conclusion: "The results of the Great Nordic Expedition were terrific and still impress us today because of their complexity, the willingness to work and the courage of the many known and unknown expedition participants and helpers," admits at the same time that "due to the inadequate preparation, implementation and inconsistent leadership, especially of the Pacific group of Berings, great mistakes were made that unnecessarily cost the lives of many people".

In contrast to the rapid publication of the newly acquired geographical knowledge, the publication of the other expedition results extended over a longer period of time and was characterized by numerous obstacles. Folkwart Wendland, who traced the dissemination of information using several examples, attributes this to both the "temporarily desolate state of the Petersburg Academy" and the restrictive information policy of the Russian government. This had imposed a strict publication ban on all expedition participants and treated the reports submitted by the researchers as classified information. The Imperial Russian Academy of Sciences was to have sole power of disposal over the new knowledge, because it had been acquired with enormous effort and, moreover, was given great economic and strategic importance. In this way, the publications of the expedition members appeared in a period between 1747 and 1793, partly forbidden and far from complete.

cartography

One of the most rapidly received results of the Second Kamchatka Expedition in Europe was the mapping of the northern and northeastern coasts of Siberia as well as Kamchatkas , the Kuril and Japanese island chain . In 1745 the Atlas Rossijskoj published by the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences appeared , which contained a general map of Russia on a scale of approximately 1: 8.9 million as well as 19 special maps of the Russian Empire . Nine years later, the Petersburg Academy published the card Nouvelle Carte des Découvertes faites par des Vaisseaux Russiens aux côtes inconnues de l'Amérique Septentrionale avec les Pais adiacents (about 1: 14 million), which also appeared in a Russian-language edition and was later reprinted several times .

With the knowledge gained during the expedition it became possible for the first time to get a more precise idea of the entire coastline of the Russian Empire, as well as the legend of the existence of fabulous countries such as the "Joao da Gama Land" or the country " Jesso “was refuted. The dream of an economic use of the Northeast Passage was shattered.

Müller: Siberian historiography

Between 1732 and 1764 Gerhard Friedrich Müller published his research results in a total of nine volumes of the monograph series Collection of Russian History . Before his return to Saint Petersburg in 1743, he had visited a large number of regional archives, where he looked through, copied and - to a lesser extent - scientifically evaluated vast amounts of documents. Among other things, he had come across papers that contained evidence that the Bering Strait had been crossed by the Cossack fur hunter and trader Semyon Deschnjow (around 1605–1673) long before Vitus Bering passed through .

Müller, who had had a tense relationship with the director of the Petersburg Academy Johann Daniel Schumacher (1690–1761) even before he left for Siberia , worked under difficult conditions after his return. Schumacher and the Russian writer and scientist Mikhail Wassiljewitsch Lomonossow (1711–1765) considered Müller to be unpatriotic and accused him of not doing his job quickly enough. At the same time, Müller was overwhelmed with tasks. Although he pledged to remain in Russia for the rest of his life in 1747, the dispute escalated in 1750 and Müller was struck off the Academy's list of professors for a year. These working conditions only improved after his admission to the management staff of the Academy's Geography Department in 1753.

Due to his outstanding achievements as a historian, Müller is now known as the "father of Siberian historiography". In the 19th century, the natural scientist Karl Ernst von Baer (1792–1876) judged Müller's achievements as part of the Second Kamchatka Expedition: “If copies had not been taken from all the Siberian archives under Müller's direction, this news would have long been lost . "

Gmelin: botany and travelogue

The natural scientist Johann Georg Gmelin published the botanical results of his trip in the multi-volume work Flora Sibirica sive historia plantarum Sibiriae (mostly Flora Sibirica for short ). While he was able to manage the publication of the first and second volumes himself in 1747 and 1749, after his death his nephew Samuel Gottlieb Gmelin (1744–1774) took over the publication of the third and fourth volumes in 1768 and 1769. The publication of the fifth volume, already in manuscript form, could never be realized. In his description of the Siberian flora, Gmelin mentions a total of 1,178 species, which were supplemented by almost three hundred copperplate engravings based on the templates of the draftsmen Johann Christian Berckhan, Johann Wilhelm Lürsenius and Johann Cornelius Decker. In addition to this description of the plants and their detailed pictorial representation, the knowledge gained by Gmelin during the expedition in the field of geobotany should be emphasized, due to which Gmelin is now one of the founders of plant geography.

In addition to the Flora Sibirica , Gmelin, who was appointed professor of botany and chemistry at the University of Tübingen in 1749, published a detailed report on the trips of the academic group, contrary to the agreements with the Russian Academy of Sciences. This was published in four volumes in 1751 and 1752 under the title Reise durch Sibirien, from 1733 to 1743 by the widow Abraham Vandenhoeck's publishing house in Göttingen. The mathematician Leonhard Euler , with whom Gmelin corresponded, sent one of the “ corpora delicti ” from Berlin to the office of the Petersburg Academy under Johann Daniel Schumacher, who saw his doubts about Gmelin's trustworthiness confirmed. In learned Europe, on the other hand, the publication of the trip through Siberia was a great success. From today's point of view, the value of the travel description lies not only in the large number of ethnographic and geoscientific observations it contains, but also in the information on the travel course of the academic group.

Krascheninnikow: Country description

Stepan Krasheninnikov , who took part in the expedition as a student, received a professorship at the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences on his return. On behalf of the academy, he recorded his research results in the two-volume work Opisanije Zemli Kamčatki ( Eng . "Description of the country of Kamchatka"), whose publication in 1755 he did not live to see because he died shortly before.

The great interest with which the results of the expedition were received by the learned world of Europe can be seen from the publication history of this work.

- In 1764 (nine years after the Russian first edition) an abridged English translation was published.

- In 1766 a German translation was made based on the abridged English edition.

- A year later, a French version was published, also based on the abridged English edition.

- Another two years later, the French astronomer Abbé Jean Chappe d'Auteroche (1728–1769) published a new French translation based on the Russian original.

- The first Dutch translation appeared in 1770.

- A year later a German translation of the French edition of Chappe d'Auteroche was published.

- In 1786 an abridged second edition of the Russian-language original followed.

Steller: Country description and ethnography

In addition to Krasheninnikov, the doctor and naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller also wrote a report on his trip through Kamchatka. This work, published in 1774 by Johann Benedict Scherer under the title Description of the Land of Kamchatka long after Steller's death, contains detailed descriptions of the people of Kamchatka as well as precise geographical and natural history descriptions. A special feature of the work is the clear statement with which Steller condemned the suppression of the indigenous Itelmenen ethnic group by the Cossacks . Steller had already brought this position to the brink of a high treason trial during his stay on the peninsula, when he complained in a protest note sent to Saint Petersburg about the behavior of the Russian commander Vasily Chemetevski towards the Itelmens.

Not only is Steller's respect for the foreign culture of the indigenous peoples, which was unusual at the time, remarkable, but also his scientific approach. Unlike Gmelin and Müller, who carried a library of several hundred volumes with them during their trip, Steller only traveled lightly. In addition, he tried to adapt to the eating habits of the peoples he studied and used Itelmenian boats and dog sleds on his travels through Kamchatka. His interest in the naturopathy of the Itelmenen and in the question of why the indigenous people did not suffer from scurvy in contrast to the expedition members , Steller ultimately saved his life during his participation in the cruise of the Pacific group under Bering. In his epilogue to the reprint of Steller's description of the land of Kamchatka , published in 1996, the German ethnologist Erich Kasten emphasizes Steller's participation in the life of the peoples he has studied and, in his research work, makes "first approaches to the current debate about indigenous knowledge or" native knowledge “in resource management in circumpolar areas”.

The German naturalist and geographer Peter Simon Pallas (1741–1811) played a special role in the reception of Steller's work . The Russian Academy of Sciences entrusted him with the management of an expedition carried out between 1768 and 1774, which took him from the central Urals through western Siberia to the Caspian Depression . While preparing for this venture, Pallas came across materials from the Second Kamchatka Expedition. He realized that some of the documents had not yet been evaluated and published. In order to save the knowledge gained through enormous efforts from being forgotten, Pallas published a total of four works by Steller in 1781 and 1793, including his topographical and physical description of the Bering Island and the diary he wrote during the sea voyage with Bering. In addition, he published, partly in an annotated and edited form, other works by Steller in his two journals Stralsundisches Magazin and Neue Nordische Beyangebote . In addition to being a publisher, Pallas also used the collection objects and documents from the Second Kamchatka Expedition kept by the Petersburg Academy for his own publications, such as the Flora Rossica or the Zoographia Rosso-Asiatica . With the publication of the biographical sketch Reliable news of the last fate of Mr. Georg Wilhelm Steller , he made an important contribution to the life story of the German natural scientist, whose exact circumstances of death have repeatedly given rise to speculation.

Recent research on the Second Kamchatka Expedition

Since the opening of Russian archives to foreign historians in the 1990s, the scholarly discussion of the Second Kamchatka Expedition has taken off again. Together with researchers from today in Moscow -based Russian Academy of Sciences and the Danish University of Aarhus , the deal Francke Foundations , the close of the 18th century cultural, religious and scientific relations with Russia were talking intensively with the history of German-Russian scientific relations in 18 Century. In this context, among other things, the publication series "Sources on the history of Siberia and Alaska from Russian archives" was created, in which the Francke Foundations together with the archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences published previously unpublished documents and manuscripts of the expedition members in scientific-critical editions. At the same time, Russian-German exhibition projects were realized and workshops with German and Russian scientists were held. In 2005, on board a ship on the Siberian Ob River, a scientific conference entitled "300 years of academic research on Ugra - from Müller to Steinitz" took place, during which some stations of the expedition were also visited.

While most of the objects collected during the expedition were lost over the centuries or scattered across different European countries, numerous handwritten documents are still stored in the archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences and in the Russian State Archives for Old Documents (RGADA) in Moscow. A special find was made by Wieland Hintzsche, an employee of the Francke Foundations and editor of the series "Sources on the History of Siberia and Alaska from Russian Archives", who in 2001 found a travel diary of Georg Wilhelm Steller in Saint Petersburg , which was believed to be lost . It is the 330-page first part of Steller's diary, which he wrote between December 1737 and February 1739. In addition to the scientific observations, these rediscovered handwritten notes contain information about everyday life on the trip and provide new insights into Steller's travel preparations in Moscow.

The Russian researcher Natascha Ochotina Lind and the Danish historian Peter Ulf Møller found previously unknown letters from the Vitus Berings family while working in the Moscow Archive of Foreign Policy of the Russian Empire (AVPRI) . These letters - and above all the information concerning his wife Anna Christina Bering - open up insights into Bering's previously unknown private life. Anna Christina Bering accompanied her husband on the Great Northern Expedition until after Okhotsk and corresponded during the trip, among other things with her father, the Vyborger merchant Mathias Pülse (also Pylse or Piilse ) and her born in 1721 the second son of John, the high school in Tallinn visited , while two of his younger siblings took part in the expedition with their parents. A selection of these letters has since been published in an anthology from 2003 edited by Lind and Møller.

A special focus of interest is on the person and the work of Gerhard Friedrich Müller , whose birthday was in 2005 for the 300th time. Particularly noteworthy is the re-evaluation of the ethnographic aspects of the expedition carried out in this context. Gudrun Bucher was able to demonstrate, based on an examination of the instructions written by Müller in 1740 to Johann Eberhard Fischer (1697–1771), that the beginning of scientific ethnology , which so far generally relies on the work of August Ludwig von Schlözer (1735–1809) in the second Half of the 18th century, it must be attributed to Müller. Due to his poor health, Müller had applied to the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences to be recalled from the expedition at the end of 1737. The rector of the St. Petersburg Academic Gymnasium Johann Eberhard Fischer, who was then sent to Siberia, was provided with extensive instructions by Müller. The last and by far the most extensive part of these instructions with 923 individual points referred to the ethnological studies to be carried out by Fischer. If one follows Bucher, then this detailed - albeit hardly fulfilled by Fischer - research program for the systematic description of the Siberian peoples and their languages must be seen today as the beginning of modern ethnology.

literature

Modern editions of written sources

- Documents on the 2nd Kamčatka expedition 1730–1733: Academy group , edited by Wieland Hintzsche and Natasha Ochotina Lind with the collaboration of Heike Heklau, Halle 2004, ISBN 3-931479-63-3 (sources on the history of Siberia and Alaska from Russian archives, volume 4, 2)

- Georg Wilhelm Steller: Letters and Documents 1739 , edited by Wieland Hintzsche, Halle 2001, ISBN 3-930195-67-4 (Sources on the history of Siberia and Alaska from Russian archives, Volume 3)

- Georg Wilhelm Steller, Stepan Krašeninnikov, Johann Eberhard Fischer: Travel diaries 1735 to 1743 , edited by Wieland Hintzsche, Halle 2000, ISBN 3-930195-64-X (sources on the history of Siberia and Alaska from Russian archives, volume 2).

- Georg Wilhelm Steller: Letters and Documents 1740 , edited by Wieland Hintzsche, Halle 2000, ISBN 3-930195-61-5 (Sources on the history of Siberia and Alaska from Russian archives, Volume 1)

- Doris Posselt (ed.): The great Nordic expedition: from 1733 to 1743. From reports by the explorers Johann Georg Gmelin and Georg Wilhelm Steller. With 82 contemporary illustrations and 2 route maps , Munich 1990, ISBN 3-406-33596-9 (reader-friendly edition that reproduces the most interesting and typical text passages in modern spelling and punctuation).

- Carol Urness (Ed.): Bering's voyages: the reports from Russia , Fairbanks 1986, ISBN 0-912006-22-6 (translation of Gerhard Friedrich Müller's news of voyages and discoveries made at sea, published in 1758 as the third volume of his collection of Russian history with comments, illustrations and maps).

- Peter Ulf Møller / Natasha Okhotina Lind (eds.): Until death do us part: the letters and travels of Anna and Vitus Bering , translated by Anna Halager, Fairbanks 2007, ISBN 978-1-889963-94-5 .

- Sven Waxell, The American Expedition , translated by MA Michael, London, Edinburgh, Glasgow, 1952.

- FA Golder: Bering's Voyages , American Geographical Society , New York, Volume 1: 1922, Volume 2: 1925.

Contemporary reports

cards

- Wieland Hintzsche and Thomas Nickol (eds.): Monumenta Sibiriae: Sources for the history of Siberia and Alaska from Russian archives , Gotha 1996, ISBN 3-623-00480-4 (contains 19 loose cards in a folder and a booklet with explanations).

Representations

- Erich Donnert: Russia's reach out to America: a contribution to the Eurasian-American history of discovery in the 18th and early 19th centuries, Frankfurt a. M. u. a. 2009, ISBN 978-3-631-58362-3 , pp. 21-28.

- Raymond H. Fisher, Bering's Voyages. Whither and Why , Seattle and London, 1977.

- Marcus Köhler: "Description of peoples". The ethnographic method of Georg Wilhelm Steller (1709–1746) in the context of the development of the “Russian” ėtnografija , Saarbrücken 2008.

- Peter Ulf Møller / Natasha Okhotina Lind (eds.): Under Vitus Bering's Command. New perspectives on the Russian Kamchatka Expeditions , Århus 2003, ISBN 87-7288-932-2 (anthology with essays by an international group of researchers. The majority of the essays were written in connection with a workshop on the subject held in Copenhagen in 1998. The volume contains both English and as well as Russian-language contributions, which are supplemented by abstracts in the other language. Some of the contributions are based on more recent source studies that were only made possible by the opening of Russian archives to foreign historians in the 1990s. The bibliography compiled by Peter Ulf Møller is indispensable ).

- Marvin Falk (ed.): Aleksej Vladimirovič Postnikov: Exploring and mapping Alaska: the Russian America era, 1741–1867, translated by Lydia Black, Fairbanks 2015.

- Folkwart Wendland: The Russian Empire on the eve of the Great Nordic Expedition, the so-called second Kamchatka Expedition , in: Doris Posselt (Hrsg.): The Great Nordic Expedition: from 1733 to 1743. From reports by the explorers Johann Georg Gmelin and Georg Wilhelm Steller, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-406-33596-9 , pp. 332-384.

- Winkler, Martina: The Empire and the Sea Otters: Russia's Expansion into the North Pacific Area, 1700–1867, Göttingen 2016, ISBN 978-3-525-30177-7 .

Biographies of expedition participants

- Tatjana Fjodorova, Birgit Leick Lampe, Sigurd Rambusch and Tage Sorensen, Martin Spangsberg: A Danish Explorer in Russian Service , Esbjerg, no year (English with German summary on pp. 274–285).

- Vasilii A. Divin, The Great Russian Navigator, AI Chirikov , translated and annotated by Raymond H. Fisher, Fairbanks 1993 (sometimes too subjective Russian).

- P. Lauridsen: Vitus J. Bering og de russiske Opdagelsesrejser fra 1725–43 [Vitus J. Bering and the Russian voyages of discovery from 1725–43], Copenhagen 1885 ( online ).

- P. Lauridsen, Vitus Bering: The Discoverer of Bering Strait , translated by JE Olson, Chicago 1889, Reprint Freeport / NY 1969.

- Lütgen, Kurt, Vitus J. Bering , Balve 1976 (book for young people).

- Erik Amburger , Vitus Bering's Descendants in Russia , in: Personalhistorisk Tidsskrift 3, 1936, pp. 35–38.

Exhibition catalogs

- Terra incognita Siberia: the beginnings of scientific research in Siberia with the participation of German scientists in the 18th century; an exhibition by the Francke Foundations in Halle in cooperation with the archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg , Halle (Saale) 1999 (narrow volume, which reproduces the panels of the traveling exhibition greatly reduced in size and provided with brief explanations).

- Wieland Hintzsche (ed.): The Great Nordic Expedition: Georg Wilhelm Steller (1709–1746); a Lutheran explores Siberia and Alaska; an exhibition by the Francke Foundations in Halle, [12. May 1996 to January 31, 1997] , Gotha 1996, ISBN 3-623-00300-X (opulently illustrated and comprehensive exhibition catalog with introductory and very clearly written texts on the various aspects of the expedition).

Web links

One of the largest collections of historically significant writings and maps for the discovery and development of the Northeast Asian region in the 18th century is owned by the Göttingen State and University Library (SUB Göttingen). Some of these materials, which came to Germany through the mediation of the former Göttingen student Baron Georg Thomas von Asch (1729–1807) and the Göttingen scholar August Ludwig von Schlözer (1735–1809), were collected in 2001 and 2002 as part of the The project "Digitization of the rare books, maps and manuscripts for exploring Siberia from the Asch Collection" funded by the German Research Foundation was scanned and made available online. The materials are offered on the web server of the Göttingen Digitization Center (GDZ) as a digital collection with the abbreviation “Sibirica” and on the web server of the Library of Congress as part of the “Meeting of Frontiers” project.

Digital copies of the "Sibirica" collection (selection)

- Gerhard Friedrich Müller : Collection of Russian History , 9 volumes, Saint Petersburg 1732–1764 (later continued by Ewers and von Engelhardt), available online from the Goettingen SUB digitization center (contains as Volume 3: News from voyages and discoveries made at sea, which happened long ago from Russia along the coasts of the Giess Sea and on the Eastern Ocean against Japan and America , Saint Petersburg 1758).

- Johann Georg Gmelin : Flora Sibirica sive historia plantarum Sibiriae , 4 volumes, Petropoli 1747–1769, available online from the Goettingen SUB digitization center.

- Johann Georg Gmelin: Life of Mr. Georg Wilhelm Stellers , Frankfurt 1748, available online via the Goettingen SUB digitization center.

- Johann Georg Gmelin: Journey through Siberia, from the year 1733 to 1743 , 4 volumes, Göttingen 1751–1752, available online from the Goettingen SUB digitization center.

- Stepan Petrowitsch Krascheninnikow : Opisanije Zemli Kamčatki , 2 volumes, Saint Petersburg 1755, available online from the Goettingen SUB digitization center.

- Georg Wilhelm Steller : Description of the country Kamchatka, its inhabitants, their customs, names, way of life and various habits , ed. by Johann Benedict Scherer, Frankfurt a. M. [u. a.] 1774, available online from the Goettingen SUB digitization center.

Other web links

- GW Steller : Journey from Kamchatka to America with the Commander-Captain Bering , Saint Petersburg 1793, published by PS Pallas ( online ).

- Bering in Danish , University of Copenhagen (Danish).

- Maps of the Academy of Sciences St. Petersburg a. a. on the discoveries of the expedition, Bern University Library Ryh 1302 41-45, online .

Remarks

- ↑ Hintzsche / Nickol, The Great Nordic Expedition , p. 200.

- ↑ In deliberate demarcation from the traditional interpretation, for example by Raymond H. Fisher in his 1977 book Bering's voyages: whither and why , about the search for a land connection as the most important goal of the First Kamchatka Expedition, Carol Urness emphasizes the mapping of eastern Russia as the main purpose the trip. Cf. Carol Urness: The First Kamchatka Expedition in Focus , in: Møller / Lind (ed.), Under Vitus Bering's Command, Århus 2003, pp. 17–31 (summary of the theses of their 1987 book Bering's First Expedition: A re- examination based on eighteenth-century books, maps, and manuscripts ).

- ↑ Hintzsche / Nickol, The Great Nordic Expedition, p. 78.

- ↑ Johann Georg Gmelin's journey through Siberia from the year 1733–1743 , part 2, Göttingen 1751, p. 446. Available online ( memento of the original dated December 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked . Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. via the digitization center of the Lower Saxony State and University Library Göttingen .

- ↑ Johann Georg Gmelin's journey through Siberia from the year 1733–1743 , part 2, Göttingen 1751, p. 538f. Available online ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. via the digitization center of the Lower Saxony State and University Library Göttingen.

- ↑ Johann Georg Gmelin's journey through Siberia from the year 1733–1743 , part 2, Göttingen 1751, p. 538. Available online ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. via the digitization center of the Lower Saxony State and University Library Göttingen.

- ↑ Gerhard Friedrich Müller (1758): News of sea voyages and discoveries made at sea that have long since happened from Russia along the coasts of the Eismeer and on the Eastern Ocean against Japan and America (= Collection of Russian History , 3 (1-3) ). Part of the ten-volume collection of Russian history published from 1732 to 1818 . St. Petersburg: Imperial Academy of Sciences. Pp. 168-183. Available online

- ↑ Georg Wilhelm Steller, diary of his sea voyage from Petripaul's port in Kamchatka to the western coasts of America, and his incidents on the return voyage , here quoted from Posselt, The Great Nordic Expedition, p. 242.

- ↑ In the ship's diary, anchoring is dated Monday, July 20th ( old style ). The dating of the ship's diary does not take into account the crossing of the date line . In North America it was still Sunday.

- ↑ Georg Wilhelm Steller, diary of his sea voyage from the Petripaul's port in Kamchatka to the western coasts of America, and his incidents on the return voyage , here quoted from Posselt, The Great Nordic Expedition, p. 251.

- ↑ Georg Wilhelm Steller, diary of his sea voyage from the Petripaul's port in Kamchatka to the western coasts of America, and his incidents on the return voyage , here quoted from Posselt, The Great Nordic Expedition, p. 272.

- ↑ Folkwart Wendland, The Russian Empire on the Eve of the Great Nordic Expedition , in: Doris Posselt (Ed.): The Great Nordic Expedition, Munich 1990, p. 368.

- ↑ Folkwart Wendland, The Russian Empire on the eve of the Great Nordic Expedition , in: Doris Posselt (Ed.): The Great Nordic Expedition, Munich 1990, pp. 332–384, here p. 369.

- ↑ Folk waiting Wendland, The Russian Empire on the eve of the Great Northern Expedition , in: Doris Posselt (ed.): The Great Northern Expedition, Munich 1990, p 371st

- ↑ The digital version of a reprint of the Academy map made in 1758 is available online via the Gallica project of the French National Library in Paris at the address http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6700199v .

- ↑ Quoted here from Folkwart Wendland, Das Russische Reich on the eve of the Great Nordic Expedition , in: Doris Posselt (Ed.): The Great Nordic Expedition, Munich 1990, p. 365.

- ↑ Erich Kasten: Epilogue , in: Description of the country Kamtschatka by Georg Wilhelm Steller, ed. by Erich Kasten and Michael Dürr, reprint of the edition from 1774, Bonn 1996, ISBN 3-86097-031-3 , pp. 281–294, here: p. 292. The volume is available online as a PDF document via the von Kasten and Dürr operated server siberian-studies.org.

- ↑ On this, Wieland Hintzsche: The Travel Journals of Georg Wilhelm Steller , in: Møller / Lind, Under Vitus Bering's Command, Århus 2003, pp. 171–178, as well as the report in the German-language edition of the National Geographic magazine from August 2001, p. 108-111.

- ↑ In addition Natasha Ochotina Lind: The First Pianist in Okhotsk. New information on Anna Christina Bering , in: Møller / Lind, Under Vitus Bering's Command, Århus 2003, pp. 51-62.

- ↑ The Bering Letters from Okhotsk, February 1740 , in: Møller / Lind, Under Vitus Bering's Command, Århus 2003, pp. 237-269.

- ↑ Cf. Gudrun Bucher: "From Description of Sitten und Gebräuche der Völcker": the instructions of Gerhard Friedrich Müller and their meaning for the history of ethnology and historical science , Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-515-07890-8 , and the same: Gerhard Friedrich Müller's Instructions and the Beginning of Scientific Ethnography , in: Møller / Lind, Under Vitus Bering's Command, Århus 2003, pp. 135-144.

- ^ Library of Congress , Meeting of Frontiers: Collections from Goettingen State and University Library (SUB) - The Georg von Asch Collection .