United States Marine Corps: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m Undid revision 139332844 by 24.187.76.203 (talk) Would be hard to prove most. |

||

| Line 496: | Line 496: | ||

===Relationship with other services=== |

===Relationship with other services=== |

||

The Marine Corps combat capabilities in |

The Marine Corps combat capabilities in some ways overlap those of the [[United States Army|U.S. Army]], the latter having historically viewed the Corps as encroaching on the Army's capabilities and competing for funding, missions, and renown. The attitude dates back to the founding of the [[Continental Marines]], when General [[George Washington]] refused to allow the initial Marine battalions to be drawn from among his [[Continental Army]]. Most significantly, in the aftermath of World War II, Army efforts to restructure the American defense establishment included the dissolution of the Corps and the folding of its capabilities into the other services. Leading this movement were such prominent Army officers as General [[Dwight D. Eisenhower]] and [[Army Chief of Staff]] [[George C. Marshall]].<ref name="Krulak" /> |

||

The Marine Corps is a partner service with the [[United States Navy|U.S. Navy]] under the Department of the Navy. As a result, the Navy and Marine Corps have a close relationship, more so than with other branches of the [[Military of the United States|United States military]]. Whitepapers and promotional literature of the 20th century have commonly used the phrase "Navy-Marine Corps Team".<ref name="Seapower21">{{cite journal |

The Marine Corps is a partner service with the [[United States Navy|U.S. Navy]] under the Department of the Navy. As a result, the Navy and Marine Corps have a close relationship, more so than with other branches of the [[Military of the United States|United States military]]. Whitepapers and promotional literature of the 20th century have commonly used the phrase "Navy-Marine Corps Team".<ref name="Seapower21">{{cite journal |

||

Revision as of 01:30, 20 June 2007

The United States Marine Corps (USMC) is a branch of the United States military responsible for providing power projection from the sea,[1] utilizing the mobility of the U.S. Navy to rapidly deliver combined-arms task forces. Alongside the U.S. Navy, the Marine Corps operates as a part of the United States Department of the Navy.

Originally organized as the Continental Marines on November 10 1775 as naval infantry, the Marine Corps has evolved in its mission with changing military doctrine and American foreign policy. The Marine Corps has served in every American armed conflict including the Revolutionary War. It attained prominence in the 20th century when its theories and practice of amphibious warfare proved prescient and ultimately formed the cornerstone of the Pacific campaign of World War II.[2] By the mid 20th century, the Marine Corps had become the dominant theorist of amphibious warfare.[3][4][5] Its ability to rapidly respond to regional crises has made, and continues to make, it an important body in the implementation and execution of American foreign policy.[6]

The United States Marine Corps, with 180,000 active duty and 40,000 reserve Marines as of 2005, is the smallest of the United States' armed forces in the Department of Defense (the Coast Guard, about one fifth the size of the Marine Corps, is under the Department of Homeland Security). The Corps is nonetheless larger than the entire armed forces of many significant military powers; for example, it is larger than the Israel Defense Forces.[7][8]

Mission

The United States Marine Corps serves as an amphibious force-in-readiness. Today, it has three primary areas of responsibility as outlined in 10 U.S.C. § 5063, originally introduced under the National Security Act of 1947:

- The seizure or defense of advanced naval bases and other land operations to support naval campaigns;

- The development of tactics, technique, and equipment used by amphibious landing forces; and

- "Such other duties as the President may direct."

The quoted clause, while seemingly a consequence of the President's position as Commander-in-Chief, is a codification of the expeditionary duties of the Marine Corps. It derives from similar language in the Congressional Acts "For the Better Organization of the Marine Corps" of 1834, and "Establishing and Organizing a Marine Corps" of 1798. In 1951, the House of Representatives' Armed Services Committee called the clause "one of the most important statutory—and traditional—functions of the Marine Corps." It noted that the Corps has more often than not performed actions of a non-naval nature, including its famous actions in the War of 1812, at Tripoli, Chapultepec (during the Mexican-American War), numerous counter-insurgency, and occupational duties in Central America and East Asia, World War I and the Korean War. While these actions are not accurately described as support of naval campaigns nor as amphibious warfare, their common thread is that they are of an expeditionary nature, using the mobility of the Navy to provide timely intervention in foreign affairs on behalf of American interests.[9]

In addition to its primary duties, the Marine Corps undertakes missions in support of the White House and the State Department. President Thomas Jefferson dubbed the Marine Band the "President's Own" for its role of providing music for state functions at the White House.[10] In addition, Marines guard presidential retreats, including Camp David,[11] and the Marines of the Executive Flight Detachment of HMX-1 provide VIP helicopter transport to the President and Vice President, using the call signs "Marine One" (when the President is aboard) and "Marine Two" (when the Vice President is aboard). By authority of the 1946 Foreign Service act, the Marines of the Marine Embassy Security Command provide security for American embassies, legations, and consulates at over 110 State Department posts overseas.[12]

Historical mission

At its founding, the Marine Corps was composed of infantry serving aboard naval vessels and was responsible for the security of the ship and her crew by conducting offensive and defensive combat during boarding actions, and defending the ship's officers from mutiny; to the latter end, their quarters on ship were often strategically positioned between the officers' quarters and the rest of the vessel. Continental Marines, as they were known at the time, were also responsible for manning raiding parties, both at sea and ashore. The role of the Marine Corps has since expanded significantly; as the importance of its original naval mission declined with changing naval warfare doctrine and the professionalization of the Naval service, the Corps adapted by focusing on what were formerly secondary missions ashore. The Advanced Base doctrine of the early 20th century codified their combat duties ashore, outlining the use of Marines in the seizure of bases and other duties on land to support naval campaigns. The Marines would also develop tactics and techniques of amphibious assault on defended coastlines in time for use in World War II.[13] Its original mission of providing shipboard security finally ended in the 1990s, when the last Marine security detachments were withdrawn from U.S. Navy ships.

Capabilities

While the Marine Corps does not employ any unique combat arms, it has, as a force, the unique ability to rapidly deploy a combined-arms task force to almost anywhere in the world within days. The basic structure for all deployed units is a Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF) that integrates a ground combat component, an air component, and a logistics combat component under a common command element. While the creation of joint commands under the Goldwater-Nichols Act has improved interservice coordination between the U.S. military services, the Corps' ability to permanently maintain integrated multi-element task forces under a single command provides a smoother implementation of combined-arms warfare principles.[2]

The close integration of disparate Marine units stems from an organizational culture centered around the infantry. Every other Marine capability exists to support the infantry. Unlike many Western militaries, the Corps remained conservative against theories proclaiming the ability of new weapons to win wars independently. For example, Marine Aviation has always been focused on close air support and has remained largely uninfluenced by airpower theories proclaiming that strategic bombing can singlehandedly win wars.[13]

This focus on the infantry is matched with the fact that "Every Marine is a rifleman," emphasizing the infantry combat abilities of every Marine. All enlisted Marines receive training first and foremost as a rifleman; all officers receive training as infantry platoon commanders.[14] The value of this culture has been demonstrated many times throughout history. For example, at Wake Island, when all the Marine aircraft were shot down, their pilots continued the fight as riflemen, leading supply clerks and cooks in a final defensive effort.[15]

The amphibious assault techniques developed for World War II evolved, with the addition of air assault and maneuver warfare doctrine, into the current "Operational Maneuver from the Sea" doctrine of power projection from the seas.[1] The Marines are credited with the development of helicopter insertion doctrine and were the earliest in the American military to widely adopt maneuver-warfare principles, which emphasize low-level initiative and flexible execution. As a result, a large degree of initiative and autonomy is expected of junior Marines, particularly the NCOs, (corporals and sergeants), as compared with many other military organizations. The Marine Corps emphasizes authority and responsibility downward to a greater degree than the other military services. Flexibility of execution is implemented via an emphasis on "commander's intent" as a guiding principle for carrying out orders; specifying the end state but leaving open the method of execution.[16]

The U.S. Marine Corps relies on the U.S. Navy for sealift to provide its rapid deployment capabilities. In addition to basing a third of the Marine Corps Operating Forces in Japan, Marine Expeditionary Units (MEU), smaller MAGTF, are typically stationed at sea. This allows the ability to function as first responders to international incidents. The U.S. Army now maintains light infantry units capable of rapid worldwide deployment, though they do not match the combined-arms integration of a MAGTF, nor do they have the logistical training that the Navy provides.[2] For this reason, the Corps is often assigned to non-combat missions such as the evacuation of Americans from unstable countries and humanitarian relief of natural disasters. In larger conflicts, Marines act as a stopgap, to get into and hold an area until larger units can be mobilized. The Corps performed this role in World War I, the Korean War, and Operation Desert Storm, where Marines were the first significant combat units deployed from the United States and held the line until the country could mobilize for war.[17]

History

Origins

The United States Marine Corps traces its institutional roots to the Continental Marines of the American Revolutionary War, formed at Tun Tavern in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania by a resolution of the Continental Congress on November 10 1775, a date regarded and celebrated as the birthday of the Marine Corps. At the end of the American Revolution in 1783, both the Continental Navy and Continental Marines were disbanded, and although individual Marines were enlisted for the few American naval vessels left, the institution itself would not be resurrected until 1798. In preparation for the Naval War with France, Congress created the United States Navy and Marine Corps.[18] The U.S. Marines' most famous action of this period occurred during the First Barbary War (1801–1805), when William Eaton and First Lieutenant Presley O'Bannon led seven Marines and 300 Arab and European mercenaries in an effort to capture Tripoli. Though they only reached Derna, the action at Tripoli has been immortalized in the Marines' hymn and the Mameluke Sword carried by Marine officers.[19]

During the War of 1812, Marine naval detachments took part in the great frigate duels that characterized the war, which were the first American victories in the conflict. Their most significant contributions came at the Battle of Bladensburg and the defense of New Orleans. At Bladensburg, they held the line after the Army and militias retreated, and although eventually defeated, they inflicted casualties on the British and delayed their march to Washington, D.C. At New Orleans, the Marines held the center of Gen. Andrew Jackson's defensive line. By the end of the war, the Marines had acquired a well-deserved reputation as expert marksmen, especially in ship-to-ship actions.[19]

After the war, the Marine Corps fell into a depression. The third and fourth commandants were court-martialed. However, the appointment of Archibald Henderson as its fifth commandant in 1820 breathed new life into the Corps; he would go on to become the Corps' longest-serving commandant. Under his tenure, the Corps took on expeditionary duties in the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, Key West, West Africa, the Falkland Islands, and Sumatra. Commandant Henderson is credited with thwarting President Andrew Jackson's attempts to combine and integrate the Marine Corps with the Army.[19] Instead, Congress passed the Act for the Better Organization of the Marine Corps in 1834, stipulating that the Corps was part of the Department of the Navy as a sister service to the U.S. Navy.[20] This would be the first of many times that Congress came to the aid of the Marines.

When the Seminole Wars of 1835 broke out, Commandant Henderson volunteered the Marines for service, himself personally leading two battalions, nearly half of the entire Corps, to war. A decade later, in the Mexican–American War (1846–1848), the Marines made their famed assault on Chapultepec Palace, an imposing complex overlooking Mexico City. The Marines were placed on guard duty at the Mexican Presidential Palace, hence the phrase "The Halls of Montezuma" in the Marines' hymn. In the 1850s, the Marines would further see service in Panama and Asia, escorting Matthew Perry's East India Squadron on its historic trip to the Far East. Colonel Archibald Henderson is known affectionately as "The Grand Old Man" of the Marine Corps, based on his many contributions during his 39 years as Commandant.[21]

Despite their vast service in foreign engagements, the Marine Corps played only a minor role in the Civil War (1861–1865); their most important task was blockade duty. As more and more states seceded from the Union, about half of the officers in the Marine Corps also left the Union to join the Confederacy. Without most of its officers, the remaining Marines were few and inexperienced. The battalion of recruits formed for the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas) performed poorly, retreating with the rest of the Union forces. The Confederate Congress authorized the formation of a Marine Corps of its own, to be made up of ten companies, but this organization had little impact on the war.[17]

Formative years

The remainder of the 19th century was marked by declining strength and introspection about the mission of the Marine Corps. The U.S. Navy's transition from sail to steam put into question the need for Marines on naval ships. Meanwhile, Marines served as a convenient resource for interventions and landings to protect American lives and interests overseas. The Corps was involved in over 28 separate interventions in the 30 years from the end of the American Civil War to the end of 19th century, including China, Formosa, Japan, Nicaragua, Uruguay, Mexico, Korea, Panama, Hawaii, Egypt, Haiti, Samoa, Argentina, Chile, and Colombia. They would also be called upon to stem political and labor unrest within the United States.[22] During this period, war correspondent Richard Harding Davis coined the phrase "The Marines have landed and have the situation well in hand." Under Commandant Jacob Zeilin's tenure, Marine customs and traditions took shape: the Corps adopted the Marine Corps emblem on November 19 1868. It was also during this time that "The Marines' Hymn" was first heard. Around 1883, the Marines adopted their current motto "Semper Fidelis" (Latin: Always Faithful).[19]

John Philip Sousa, the musician and composer, enlisted as a Marine apprentice at the age of 13, serving from 1867 until 1872. He would later return to Corps service from 1880 to 1892 as the leader of the U.S. Marine Band (The President's Own). (His father, John Antonio Sousa, had been a trombonist in the same band.)

During the Spanish–American War (1898), Marines led U.S. forces ashore in the Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico, demonstrating their readiness for deployment. At Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, the Marines seized an advanced naval base that remains in use today by the U.S. Navy. Between 1899 and 1916, the Corps continued its record of participation in foreign expeditions, including the Philippine-American War, the Boxer Rebellion in China (1899–1901), Panama, the Cuban Pacifications, Veracruz (Mexico), Haiti, Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic), and in Nicaragua. In the 1900s and 1910s, the seizure of advance naval bases entered Marine Corps doctrine with the formation of the Marine Corps Advanced Base School and the Advanced Base Force, the prototype of the Fleet Marine Force.[21]

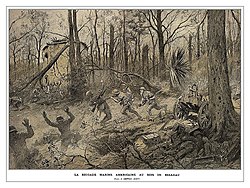

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, before and after World War I, Marines saw action throughout Central America, including Haiti and Nicaragua. These actions became known as the "Banana Wars" after the principal export of those countries. The experiences gained in counter-insurgency and guerrilla operations during this period were consolidated into the Small Wars Manual.[23]

World War I

In World War I, battle-tested, veteran Marines served a central role in the U.S. entry into the conflict. Unlike the U.S. and British armies, the Marine Corps had a deep pool of officers and NCOs with battle experience, and experienced a relatively smaller expansion. Here, the Marines fought their celebrated battle at Belleau Wood, then the largest in the history of the Corps; it created the Marines' reputation in modern history. Rallying under the battle cries of "Retreat? Hell, we just got here!" (Captain Lloyd Williams) and "Come on, you sons of bitches, do you want to live forever?" (GySgt. Dan Daly), the Marines drove German forces from the area. While its previous expeditionary experiences had not earned it much acclaim in the Western world, the Marines' fierceness and toughness earned them the respect of the Germans, who rated them of stormtrooper quality.[citation needed] Though Marines and American media reported that Germans had nicknamed them Teufel Hunden as meaning "Devil Dogs," there is no evidence of this in German records and since Teufelshunde would be the proper German phrase, it was possibly American propaganda. Nevertheless, the name stuck.[24] The Corps had entered the war with 511 officers and 13,214 enlisted personnel, and by November 11 1918 had reached a strength of 2,400 officers and 70,000 men.[25]

Between the World Wars, the Marine Corps was headed by Commandant John A. Lejeune. Under his leadership, the Corps presciently studied and developed amphibious techniques that would be of great use in World War II. Many officers, including Lt. Col. Earl Hancock "Pete" Ellis, foresaw a war in the Pacific with Japan and took preparations for such a conflict. While stationed in China, then-Lt. Col. Victor H. Krulak observed Japanese amphibious techniques in 1937. Through 1941, as the prospect of war grew, the Corps pushed urgently for joint amphibious exercises and acquired amphibious equipment such as the Higgins boat which would prove of great use in the upcoming conflict.[26]

World War II

In World War II, the Marines played a central role in the Pacific War; the Corps expanded from two brigades to two corps with six divisions and five air wings with 132 squadrons. In addition, 20 defense battalions and a parachute battalion were set up.[27] The battles of Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Saipan, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa saw fierce fighting between U.S. Marines and the Imperial Japanese Army.

During the battle of Iwo Jima, photographer Joe Rosenthal took the famous photograph Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima of five Marines and one Navy corpsman raising the American flag on Mt. Suribachi. Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, who had come ashore earlier that day to observe the progress of the troops, said of the flag raising on Iwo Jima, "...the raising of that flag on Suribachi means a Marine Corps for the next five hundred years." The acts of the Marines during the war added to their already significant popular reputation. The USMC War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia was dedicated in 1954. By war's end, the Corps had grown to include six divisions, five air wings, and supporting troops totaling about 485,000. Nearly 87,000 Marines were killed or wounded during World War II and 82 received the Medal of Honor.[28]

Despite Secretary Forrestal's prediction, the Corps faced an immediate institutional crisis following the war. Army generals pushing for a strengthened and reorganized defense establishment also attempted to fold the Marine mission and assets into the Navy and Army. Drawing on hastily assembled Congressional support, the Marine Corps rebuffed such efforts to dismantle the Corps, resulting in statutory protection of the Marine Corps in the National Security Act of 1947.[29] Shortly afterward, in 1952 the Douglas-Mansfield Bill afforded the Commandant an equal voice with the Joint Chiefs of Staff on matters relating to the Marines and established the structure of three divisions and air wings that remains today. This allowed the Corps to permanently maintain a division and air wing in the Far East and participate in various small wars in Southeast Asia—in the Tachen Islands, Taiwan, Laos, Thailand, and South Vietnam.[2]

Korean Conflict

The Korean War (1950–1953) saw the hastily formed Provisional Marine Brigade holding the defensive line at the Pusan Perimeter. To execute a flanking maneuver, General Douglas MacArthur called on Marine air and ground forces to make an amphibious landing at Inchon. The successful landing resulted in the collapse of North Korean lines and the pursuit of North Korean forces north near the Yalu River until the entrance of the People's Republic of China into the war. Chinese troops surrounded, surprised and overwhelmed the overextended and outnumbered American forces. However, unlike the Eighth Army, which retreated in disarray, the 1st Marine Division regrouped and inflicted heavy casualties during their fighting withdrawal to the coast. Now known as the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, it entered Marine lore as an example of toughness and resolve. Marines would continue a battle of attrition around the 38th Parallel until the 1953 armistice.[30] The Korean War saw the Corps expand from 75,000 regulars to a force, by the end of the conflict in 1953, of 261,000 Marines, most of whom were reservists. 30,544 Marines were killed or wounded during the war and 42 were awarded the Medal of Honor.[31]

Vietnam War

The Marine Corps served an important role in the Vietnam War by partaking in such battles as Da Nang, Hue City, and Khe Sanh. Individuals from the USMC operated in the Northern I Corps Regions of South Vietnam. While there, they were constantly engaged in a guerilla war against the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF) and an intermittent conventional war against the North Vietnamese Army (NVA). Portions of the Corps were responsible for the less-known combined action program (CAC) that implemented unconventional techniques for counter-insurgency (COIN).

Vietnam was the longest war for Marines; by its end, 13,091[32] were killed in action, 51,392 were wounded, and 57 Medals of Honor were awarded.[33][34] Due to policies concerning rotation, more Marines were deployed for service during Vietnam than World War II.[35] The USMC presence was withdrawn in 1971, and returned briefly in 1975 to evacuate Saigon and in an attempt to rescue the crew of the Mayagüez.[36] While recovering from Vietnam, the Corps hit a detrimental low point in its service history caused by courts-martial and Non-Judicial Punishments related partially to increased Unauthorized Absences and Desertions during the war. Overhauling of the Corps began in the late 1970s when discharge policies for inadequate Marines relaxed, resulting in the removal of only the most delinquent. Once quality of new recruits improved, the Corps could focus on reforming the NCO Corps, a vital functioning part of its forces.[2]

Post-Vietnam and pre-9/11

After Vietnam, the Marines resumed their expeditionary role, participating in the invasion of Grenada (Operation Urgent Fury) and the invasion of Panama (Operation Just Cause). On October 23 1983, the Marine headquarters building in Beirut, Lebanon was bombed, causing the highest peacetime losses to the Corps in its history (220 Marines and 21 other service members of the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit were killed) and leading to the American withdrawal from the country. The year of 1990 saw Marines of the Joint Task Force Sharp Edge save thousands of lives by evacuating the British, French and American Nationals from the violence of the Liberian Civil War. During the Persian Gulf War (1990–1991), Marine task forces formed the initial core for Operation Desert Shield, while U.S. and Coalition troops mobilized, and later liberated Kuwait in Operation Desert Storm.[19] U.S. Marines participated in combat operations in Somalia (1992–1995) during Operations Restore Hope, Restore Hope II, and United Shield to provide humanitarian relief.[37]

Global war on terrorism

Following the September 11, 2001 attacks President Bush declared a War on Terrorism. The stated objective of the Global War on Terror is "the defeat of al Qaeda, other terrorist groups and any nation that supports or harbors terrorists".[38] Since that time the United States Marine Corps, along with other military and federal agencies, has engaged in global operations including Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom as part of that mission.

Operation Enduring Freedom

Marines and other U.S. forces began staging in Uzbekistan on the border of Afghanistan as early as October, 2001 in preparation for the invasion of Afghanistan.[39] The 15th and 26th Marine Expeditionary Units were the first conventional forces into Afghanistan in support of Operation Enduring Freedom in November of 2001 when they seized an airfield outside of Khandahar.[40] Since then Marine battalions and squadrons have been rotating through, engaging Taliban and Al-Qaeda forces. In 2002, Combined Joint Task Force - Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA) was stood up at Camp Lemonier to provide regional security.[41] Despite transfering overall command to the U.S. Navy in 2006 the Marines have continued to operate in the Horn of Africa into 2007.[42]

Operation Iraqi Freedom

Most recently, the Marines have served prominently in Operation Iraqi Freedom. The I Marine Expeditionary Force, along with the Army's 3rd Infantry Division, spearheaded the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[43] During the occupation of Iraq, Marines spearheaded both assaults on the city of Fallujah in April and November 2004.[44] Their time in Iraq has also courted controversy with the Haditha killings and the Hamdania incident.[39] [45] They currently continue to operate in the Al Anbar province in western Iraq.

Organization

The Department of the Navy, led by the Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV), administers both the Marine Corps and the Navy. The most senior Marine officer is the Commandant of the Marine Corps, responsible for organizing, recruiting, training, and equipping the Marine Corps so that it is ready for operation under the command of the Unified Combatant Commanders. The Marine Corps is organized into four principal subdivisions: Headquarters Marine Corps (HQMC), the Operating Forces, the Supporting Establishment, and the Marine Forces Reserve (MARFORRES or USMCR).

The Operating Forces are further subdivided into three categories: Marine Corps Forces (MARFOR) assigned to unified commands, Marine Corps Security Forces guarding high-risk naval installations, and Marine Corps Security Guard detachments at American embassies. Under the "Forces for Unified Commands" memo, Marine Corps Forces are assigned to each of the regional unified commands at the discretion of the Secretary of Defense and with the approval of the President. Since 1991, the Marine Corps has maintained component headquarters at each of the regional unified combatant commands.[46] Marine Corps Forces are further divided into Marine Forces Command (MARFORCOM) and Marine Forces Pacific (MARFORPAC), each headed by a Lieutenant General. MARFORCOM has operational control of the II Marine Expeditionary Force; MARFORPAC has operational control of the I Marine Expeditionary Force and III Marine Expeditionary Force.[17]

The Supporting Establishment includes Marine Corps Combat Development Command (MCCDC), Marine Corps Recruit Depots, Marine Corps Logistics Command, Marine bases and air stations, Recruiting Command, and the Marine Band.

Relationship with other services

The Marine Corps combat capabilities in some ways overlap those of the U.S. Army, the latter having historically viewed the Corps as encroaching on the Army's capabilities and competing for funding, missions, and renown. The attitude dates back to the founding of the Continental Marines, when General George Washington refused to allow the initial Marine battalions to be drawn from among his Continental Army. Most significantly, in the aftermath of World War II, Army efforts to restructure the American defense establishment included the dissolution of the Corps and the folding of its capabilities into the other services. Leading this movement were such prominent Army officers as General Dwight D. Eisenhower and Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall.[29]

The Marine Corps is a partner service with the U.S. Navy under the Department of the Navy. As a result, the Navy and Marine Corps have a close relationship, more so than with other branches of the United States military. Whitepapers and promotional literature of the 20th century have commonly used the phrase "Navy-Marine Corps Team".[47][48] Both the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) and Commandant of the Marine Corps, heads of their respective services, report directly to the Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV), a civilian who heads the Department of the Navy.

Cooperation between the two services begins with the training and instruction of Marines. The Corps receives a significant portion of its officers from the United States Naval Academy and Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps (NROTC), which are staffed by Marines alongside naval officers. Marine Corps drill instructors contribute to training of naval officers in the Navy's Officer Candidate School. Marine aviators are trained in the Naval Aviation training pipeline.

Training alongside each other is viewed as critical, as the Navy provides transport, logistical, and combat support to put Marine units into the fight. Navy aircraft carriers typically deploy with a Marine F/A-18 Hornet squadron alongside Navy squadrons. Since the Marines do not train chaplains or medical personnel, officers and enlisted sailors from the Navy fill these roles. Some of these sailors, particularly Hospital Corpsmen, generally wear Marine uniforms emblazoned with Navy insignia and markings in order to be noticeably distinct to compatriots but generally indistinguishable to enemies. Conversely, the Marine Corps is responsible for conducting land operations to support naval campaigns, including the seizure of naval and air bases. Both services operate a network security team in conjunction.

Finally, there are several traditional connections between the two services. Marine Corps Medal of Honor recipients wear the Navy variant of the award; Marines also may be awarded the Navy Cross.[13] The Navy's Blue Angels flight demonstration team includes at least one Marine pilot, and is supported by a Marine C-130 Hercules aircraft.[13] In cities with Navy and Marine Corps presence, social activities are often conducted together, for example with the Navy/Marine ball in San Diego.

Air-ground task forces

Today, the basic framework for deployable Marine units is the Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF), a flexible structure of varying size. A MAGTF integrates a ground combat element (GCE), an air combat element (ACE), and a logistics combat element (LCE)[49] under a common command element (CE). A MAGTF can operate independently or as part of a larger coalition. It is a temporary organization formed for a specific mission and dissolved after completion of that mission. The MAGTF structure reflects a strong tradition in the Corps towards self-sufficiency and a commitment to combined arms, both essential assets to an expeditionary force often called upon to act independently in discrete, time-sensitive situations. The history of the Marine Corps as well has led to a wariness of overreliance on its sister services, and towards joint operations in general.[2]

A MAGTF varies in size from the smallest, a Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU), based around a reinforced infantry battalion and a composite squadron, up to the largest, a Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF), which ties together a Division, an Air Wing, and a Logistics Group under a MEF Headquarters Group. There are usually three MEUs assigned to each of the Navy's Atlantic and Pacific Fleets, with a seventh MEU based on Okinawa. While one MEU is on deployment, one MEU is training to deploy and one is standing down, resting its Marines and refitting. Each MEU is rated as capable of performing special operations.[50]

The three Marine Expeditionary Forces are:

- I Marine Expeditionary Force located at Camp Pendleton, California

- II Marine Expeditionary Force located at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina

- III Marine Expeditionary Force located at Camp Courtney, Okinawa, Japan

Special warfare

Although the notion of a Marine special forces contribution to the U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) was considered as early as the founding of USSOCOM in the 1980s, it was resisted by the Marine Corps. Then-Commandant Paul X. Kelley expressed the popular belief that Marines should support Marines, and that the Corps should not fund a special warfare capability that would not support Marine operations.[51] However, much of the resistance from within the Corps dissipated when Marine leaders watched the Corps' 15th and 26th MEU(SOC)s "sit on the sidelines" during the very early stages of Operation Enduring Freedom while other special operations units actively engaged in operations in Afghanistan.[52] After a three-year development period, the Corps agreed in 2006 to supply a 2,600-strong unit, Marine Forces Special Operations Command (MARSOC), which would answer directly to USSOCOM.[53]

Personnel

Commandants

The Commandant of the Marine Corps is the highest-ranking officer of the Marine Corps, though he may not be the senior officer in time and grade. He is both the symbolic and functional head of the Corps, and holds a position of very high esteem among Marines. The commandant has the U.S. Code Title 10 responsibility to man, train, and equip the Marine Corps. He does not serve as a direct battlefield commander. The Commandant is a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and reports to the Secretary of the Navy.[9]

The current and 34th Commandant of the Marine Corps is General James T. Conway; his nomination was confirmed by the Senate on August 2 2006. Conway was then promoted to general, and assumed command as the 34th Commandant of the Marine Corps on November 13 2006.[54] As of February 2007, Marine Generals Peter Pace (Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) and James E. Cartwright (Commander of the United States Strategic Command) are senior in terms of time in grade to the commandant.[55]

Rank structure

As in the rest of the U.S. military, ranks fall into one of three categories: commissioned officer, warrant officer, and enlisted, in decreasing order of authority. To standardize compensation, each rank is assigned a pay grade. The following tables list the rank, abbreviation, pay grade, and insignia of each rank.[56]

Commissioned officers

Commissioned Officers are distinguished from other officers by their commission, which is the formal written authority, issued in the name of the President of the United States, that confers the rank and authority of a Marine Officer. Commissioned officers carry the "special trust and confidence" of the President of the United States. Commissioned officer ranks are further subdivided into Generals, field-grade officers, and company-grade officers.[9]

| Commissioned Officer Rank Structure of the United States Marine Corps | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Officers | ||||||||||

| General (Gen) | Lieutenant General (LtGen) | Major General (MajGen) | Brigadier General (BGen) | |||||||

| O-10 | O-9 | O-8 | O-7 | |||||||

| Field-grade Officers | ||

|---|---|---|

| Colonel (Col) | Lieutenant Colonel (LtCol) | Major (Maj) |

| O-6 | O-5 | O-4 |

|

|

|

| Company-grade Officers | ||

| Captain (Capt) | First Lieutenant (1stLt) | Second Lieutenant (2ndLt) |

| O-3 | O-2 | O-1 |

Warrant officers

Warrant Officers provide leadership and skills in specialized fields. Unlike most other militaries, the American military confers commissions on its Warrant Officers, though they are generally not responsible for leadership outside of their specialty. Warrant officers come primarily from the senior Non-Commissioned Officer ranks.

A Chief Warrant Officer, CWO2-CWO5, serving in the MOS 0306 "Infantry Weapons Officer" carries a special title, "Marine Gunner" (not a rank). A Marine Gunner replaces the Chief Warrant Officer insignia on the left collar with a bursting bomb insignia. Other warrant officers are sometimes informally also referred to as "Gunner," but this usage is not correct.

Enlisted

Enlisted Marines in the pay grades E-1 to E-3 are not "non-commissioned officers" (NCOs) and are generally referred to as "non-NCOs"; they make up the bulk of the Corps' ranks. They are also often referred to as "non-rates" which is a reference to the tradition in the U.S. Navy of not assigning a specific job skill or "rate" to sailors until they reach Petty Officer rank. As every Marine has a job skill assigned upon completion of initial entry training, the term "non-rate" is not technically or logically correct. Although they don't technically hold leadership ranks, the Corps' ethos stresses leadership among all Marines, and junior Marines are often assigned responsibility normally reserved for superiors.

Those in the pay grades of E-4 and E-5 are non-commissioned officers. They primarily supervise junior Marines and act as a vital link with the higher command structure, ensuring that orders are carried out correctly. Marines E-6 and higher are Staff Non-Commissioned Officers (SNCOs), charged with supervising NCOs and acting as enlisted advisors to the command.

The E-8 and E-9 levels each have two ranks per pay grade, each with different responsibilities. Gunnery Sergeants (E-7) indicate on their annual evaluations, called "fitness reports", or "fitreps" for short, their preferred promotional track: Master Sergeant or First Sergeant. The First Sergeant and Sergeant Major ranks are command-oriented, with Marines of these ranks serving as the senior enlisted Marines in a unit, charged to assist the commanding officer in matter of discipline, administration and the morale and welfare of the unit. Master Sergeants and Master Gunnery Sergeants provide technical leadership as occupational specialists in their specific MOS. First Sergeants typically serve as the senior enlisted Marine in a company, battery or other unit at similar echelon, while Sergeants Major serve the same role in battalions, squadrons or larger units.

The Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps is a unique rank conferred on the senior enlisted Marine of the entire Marine Corps, personally selected by the Commandant of the Marine Corps. The Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps wears unique chevrons with the Eagle, Globe, and Anchor at the center, flanked by two five-point stars.

| Staff Noncommissioned Officer (SNCO) Rank Structure of the United States Marine Corps | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps (SgtMajMC) | Sergeant Major (SgtMaj) | Master Gunnery Sergeant (MGySgt) | First Sergeant (1stSgt) | Master Sergeant (MSgt) | Gunnery Sergeant (GySgt) | Staff Sergeant (SSgt) | ||||

| E-9 | E-9 | E-9 | E-8 | E-8 | E-7 | E-6 | ||||

| Noncommissioned Officer (NCO) Rank Structure of the United States Marine Corps | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sergeant (Sgt) | Corporal (Cpl) | |||||||||

| E-5 | E-4 | |||||||||

| Enlisted Rank Structure of the United States Marine Corps | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lance Corporal (LCpl) | Private First Class (PFC) | Private (Pvt) | ||||||||

| E-3 | E-2 | E-1 | ||||||||

Forms of address

Junior Marines, those not yet non-commissioned officers, are typically addressed by their last names. Non-commissioned officers are addressed by rank and last name. All officers, both commissioned and warrant, are addressed as "sir" or "ma'am". Warrant Officers are sometimes informally addressed as "Gunner", although the usage of this term is improper unless the Warrant Officer holds the Military Occupational Specialty of Infantry Weapons Officer (MOS 0306). Addressing an officer by his or her rank is a technically accepted, but rarely used and often frowned upon, form of courtesy.

During recruit training, recruits are not considered full-fledged Marines; as a result, all Marines who have completed recruit training are addressed as "sir" or "ma'am" by incoming recruits who are beginning recruit training.

Informally, some enlisted ranks have commonly used nicknames, though they are not official and are technically improper. A Gunnery Sergeant is typically called "Gunny" and (much less often) "Guns", a Master Sergeant is commonly called "Top", and a Master Gunnery Sergeant is "Master Guns" or "Master Gunny". He also may be called "Top." Differing from the US Army and Air Force, all ranks containing "Sergeant" are always addressed by their full rank and never shortened to simply "Sergeant" or "Sarge". A Private First Class is usually referred to as a PFC.

Initial training

Officers

Every year, approximately 1600 new Marine officers are commissioned, and 38,000 recruits accepted and trained.[17] Commissioned officers are commissioned mainly through one of three sources: Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps (NROTC), Officer Candidates School (U.S. Marine Corps) (OCS), or the United States Naval Academy (USNA). All officer candidates are screened and evaluated for fitness to lead Marines; OCS and NROTC graduates are screened during their tenure, and Academy graduates are screened at a month-long training program called Leatherneck.

Following commissioning, all Marine commissioned officers, regardless of accession route or further training requirements, attend The Basic School (TBS) at Marine Corps Base Quantico, Virginia. There, they spend six months learning to command a rifle platoon. The Basic School, for second lieutenants and warrant officers learning the art of infantry and combined arms warfare, is an example of the Corps' approach to furthering the concept that "Every Marine is a rifleman".[9]

Enlisted

Enlisted Marines attend recruit training, or boot camp, at either Marine Corps Recruit Depot (MCRD) San Diego or Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, just outside Beaufort, South Carolina. Women only attend the Parris Island depot, in the Fourth Recruit Training Battalion, while males who train at Parris Island comprise the First through Third Battalions. Historically, the Mississippi River served as the dividing line which delineated who would be trained where. More recently the recruiting district system has been implemented, resulting in a more even distribution of male recruits between the two MCRD facilities. All recruits must pass an Initial Strength Test to start training. Recruits who fail to do so are placed in a Physical Conditioning Platoon, where they receive individualized attention and training until the minimum standards are reached. The number of recruits sent to boot camp in poor physical shape has risen greatly, and a growing number of recruits are sent home for lying about their previous medical and mental health history, often under pressure from their recruiters.[citation needed]

Marine recruit training is the longest among the American military services; it is 13 weeks long, compared to the U.S. Army's 9 weeks. The Marine Corps plans to cut a week of training by combining swim and team week or eliminating one of the two. Many consider recruit training challenging and demanding, while veterans of the 'old' Corps consider today's training to be too easy.

U.S. Marine Corps training has been compared to the training of the British Royal Marines, who do 32 weeks of training, the longest of any infantry unit in the world.[57] However, the Royal Marines 32-week training differs from USMC recruit training as it includes both recruit training and what would be considered in the USMC to be specialty infantry training.[57] Enlisted U.S. Marines follow their recruit training with training in their Military Occupational Specialty, which for infantry Marines, this is an additional 52-days.[58]. However, if additional training is to be taken into account, Royal Marine "specialist" training comes after their 32 week original course. Additional Royal Marine courses such as the Mountain Leader Training Cadre and in the extreme case the Royal Marines own special forces the Special Boat Service specialise Royal Marines to a level usually only found in Special Forces. Also differing from U.S. Marine recruit training, Royal Marines recruits get 5 long weekends off during the 32 weeks of their training.[59]

Following recruit training, enlisted Marines then attend School of Infantry training at Camp Geiger or Camp Pendleton, generally based upon where the Marine received their recruit training. Infantry Marines begin their Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) training immediately with the Infantry Training Battalion (ITB), while Marines in all other MOSs train for 22 days with the Marine Combat Training (MCT), learning common infantry skills, before continuing on to their MOS schools.[60]

Uniforms

Uniforms serve to distinguish Marines from members of other services and militaries. The Marine Corps has the most stable and hence most recognizable uniforms in the American military; the Blue Dress dates back to the early 19th century[17] and the service uniform to the early 20th century. Marines' uniforms are also distinct in their simplicity; Marines do not wear unit patches or U.S. flags on any of their uniforms, nor name tags on their service and formal uniforms (with some exceptions). Only a handful of skills (parachutist, air crew, explosive ordnance disposal, etc.) warrant distinguishing badges, and rank insignia is not worn on uniform headgear (with the exception of an officer's garrison service cover). While other servicemen commonly identify with a sub-group as much as or more than their service (ranger, submariner, aircrew, etc.), Marines consider it enough to be distinguished simply as a Marine, and their uniforms reflect this.

The Marines have three main uniforms: Dress, Service, and Utility.

The Marine Corps Dress uniform is the most elaborate, worn for formal or ceremonial occasions. There are three different forms of the Dress uniform, the most common being the Blue Dress Uniform. There is also a "Blue-White" Dress for summer, and Evening Dress for formal (white tie) occasions. It is also worn by Marine Corps enlisted recruiters on a daily basis. It is the only U.S. military uniform which bears all three colors of the U.S. flag.

The Blue Dress uniform, often seen in recruiting advertisements, is also often called "Dress Blues" or simply "Blues". It is equivalent in composition and use to black tie, worn at ceremonial events. It consists of a long-sleeved midnight blue coat with a standing collar, white barracks cover, plain white shirt, sky blue trousers with tan web belt or suspenders, white gloves, and black shoes and socks. The uniform may also be worn with a khaki long- or short-sleeved shirt in place of the coat. The Mameluke Sword (for officers) or NCO's sword may be worn as prescribed. NCOs, SNCOs, and Officers wear a blood stripe on their trousers.[61]

The Service Uniform was once the prescribed daily work attire in garrison; however, it has been largely superseded in this role by the utility uniform. Consisting of olive green and khaki colors, it is commonly referred to as "Greens". It is roughly equivalent in function and composition to a business suit. It consists of green trousers with khaki web belt, khaki longsleeve or shortsleeve button-up shirt, khaki necktie (with long sleeves), tie clasp, and black shoes. When worn with a green coat, it becomes the "Service Alpha" uniform, worn to formal but non-ceremonial occasions such as checking into a unit and court-martial hearings. Females wear a green necktab in place of the tie, pumps instead of shoes, and have the option of wearing a skirt instead of slacks. Marines may wear a soft garrison cap (sometimes nicknamed "piss cutter"), or a hard framed hat, which differs in design between females and males.[61]

The Utility Uniform is intended for wear in the field or for dirty work in garrison, though as noted above it has now been standardized for regular duty. It consists of camouflage blouse and trousers, tan rough-out leather boots, and green undershirt. It is rendered in MARPAT pixelated camouflage (sometimes referred to as digitals or digies) that breaks up the wearer's shape, and also serves to distinguish Marine uniforms from those of other services. There are two approved varieties of MARPAT, woodland (green/brown/black/grey) and desert (tan/brown/grey). The same boots and undershirt are worn with either pattern. In garrison, during the summer months, the sleeves of the blouse are tightly folded up to the biceps, exposing the lighter inside layer, and forming a neat cuff to present a crisper appearance to the otherwise formless uniform. In years past when Marines wore identical utilities to their Army and Air Force counterparts, this served to distinguish them as the other services have a different standard for rolling sleeves. In Haiti, the practice earned them the nickname "whitesleeves".[62]

The approved headwear for this uniform is the utility cover, an eight-pointed brimmed hat that is worn "blocked", that is, creased and peaked. In the field, a boonie cover is also authorized. Since the introduction of the Marine Corps Martial Arts Program (MCMAP), Marines have the option of substituting a color-coded rigger's belt for their web belt, indicating their level of proficiency in MCMAP. Unlike the Dress and Service uniforms, utilities are not permitted for off-base wear. Though exceptions are made for essential commuting tasks, e.g. picking up children from daycare or purchasing gas, the wear of utilities in public is otherwise ordinarily prohibited.[61]

Culture

As in any military organization, the official and unofficial traditions of the Marine Corps serve to reinforce camaraderie and set the service apart from others. The Corps' embracement of its rich culture and history is cited as a reason for its high esprit de corps.[9]

Official traditions and customs

The Marines' Hymn dates back to the 19th century and is the oldest official song in the U.S. Armed Forces. It embraces some of the most important battles the Corps had been in to that time (Chapultepec, Derna), and (informal) additional verses were created to honor later events.

The Marine motto "Semper Fidelis" means "always faithful" in Latin. This motto often appears in the shortened form "Semper Fi". It is also the name of the official march of the Corps, composed by John Phillip Sousa. It was adopted in 1868, before which the traditional mottos were "Fortitudine" (With Fortitude); By Sea and by Land, a translation of the Royal Marines' Per Mare, Per Terram; and To the Shores of Tripoli.[63]

The Marine Corps emblem is the Eagle, Globe, and Anchor. (The abbreviation "EGA" for Eagle, Globe, and Anchor is generally not accepted and frowned upon when used in the Fleet Marine Force; the majority of Marines consider the abbreviation offensive and lazy.) Adopted in its present form in 1868 by Commandant Brigadier General Jacob Zielin, it derives partially from ornaments worn by the Continental Marines and the British Royal Marines, and is usually topped with a ribbon reading "Semper Fidelis". The eagle stands for a proud country, the globe signifies world-wide service, and the fouled anchor signifies naval tradition. The eagle is a crested eagle found worldwide, not the bald eagle that appears in other American symbols and is native to North America only. The eagle is standing on the Western Hemisphere and is holding a scroll bearing the Marine Corps motto, Semper Fidelis. It is inscribed with gold letters, "Department of the Navy, United States Marine Corps.[64]

The Marine Corps seal was designated by General Lemuel C. Shepherd, and consists of the Marine emblem in bronze, the beak holding a ribbon reading "Semper Fidelis", on a scarlet and blue background with gold trim. On the seal, however, a bald eagle appears in place of the crested eagle.[63] The blue signifies naval ties, while the scarlet and gold are the official Marine Corps colors. They appear ubiquitously in the Marine Corps, particularly on signage. They also form the base colors of the flag of the United States Marine Corps.[65]

Two styles of swords are worn by Marines. The Marine Corps officers' sword is a Mameluke Sword, similar to the Persian shamshir presented to Lt. Presley O'Bannon after the Battle of Derna during the First Barbary War. After its adoption in 1825 and initial distribution in 1826, Mameluke Swords have been worn by Marine officers ever since, except during the period 1859-1875, when they were required to wear the Army's Model 1850 foot officers' sword. Since 1859, noncommissioned officers have worn the NCO sword, similar to the U.S. Army's foot officers' sword of the Civil War, making Marine NCOs, along with U.S. Cavalry NCOs, the only enlisted service members in the U.S. Armed Forces authorized to carry a sword.[17]

The Marine Corps Birthday is celebrated every year on the 10th of November. The celebrations were formalized by Commandant Lemuel C. Shepherd in 1952, outlining the cake ceremony, which would enter the Marine Drill Manual in 1956. By tradition, the first slice of cake is given to the oldest Marine present, and the second to the youngest Marine present. The celebration also includes a reading of Marine Corps Order 47, Commandant Lejeune's Birthday Message.[66]

Close Order Drill is heavily emphasized early on in a Marine's training. Formal events, such as the Marine Corps Birthday Ball or a retirement ceremony, will almost always incorporate some form of close order drill. The Marine Corps uses close order drill to teach discipline by instilling habits of precision and automatic response to orders, increase the confidence of junior officers and noncommissioned officers through the exercise of command and give Marines an opportunity to handle individual weapons.[67]

Unofficial traditions and customs

Marines have several generic nicknames, mildly derogatory when used by outsiders but complimentary when used by Marines themselves. They include "jarheads" (it was said their hats on their uniform made them look like Mason jars, or that the regulation "high and tight" haircut gave the appearance of a jar-lid). While these explanations are often repeated, the first is questionable, while the second is demonstrably false. The high and tight haircut, while a de facto standard today, is not mandated by USMC regulations, which specify a maximum hair length of 3 inches (76 mm) on the top. In the 1950s, the term jarhead was well established, while the term "high and tight" did not yet exist. Marines who chose to trim their hair closely on the sides were said to have "white sidewalls." Photos of Marines in the World War II era show haircuts that are even longer.

Other nicknames include "gyrenes" (perhaps a combination of "G.I." and "Marine"), and "leathernecks", referring to the leather collar that was a part of the Marine uniform during the Revolutionary War period. "Devil Dogs" ("Teufel Hunden", a corrupted version of the German Teufelshunde, on posters and in print) arises from the nickname reporters[68] conferred on Marines after the Battle of Belleau Wood. The German high command classified Marines as stormtrooper quality (elite troops). The bulldog has also been closely associated with the Marine Corps, and some units keep one as a mascot.[17]

A spirited cry, "Ooh-rah!", is common among Marines, being similar in function and purpose to the Army's "Hooah" cry. "Ooh-rah!" is usually either a reply in the affirmative to a question, an acknowledgment of an order, an expression of enthusiasm (real or false), or a greeting. Usage of the term appears to have began during World War II and became more firmly established after the Vietnam War. There is little agreement or authoritative documentation on where, or why, the practice originated. Apocryphal stories have arisen regarding the origin of the term, including imitations of submarine alarm klaxons, air raid sirens and modifications by English speakers of the word "kill" in languages such as Turkish and Russian. Another theory (commonly held although there is no firm data pointing toward it) is that "Oorah!" is based off the British cheer "Hurrah!".[69] "Semper Fi, Mac", was the common and preferred form of greeting in times past. This term is more than a "spirited cry" or a guttural sound. It was a proclamation of the Marine Corps Motto and a welcome greeting to the ears of those being greeted. It fostered a tie among the brethren who fought in the bloody fields of the Pacific Island-hopping campaign and all around the world.[70]

Veteran Marines

Marines and those familiar with Marine Corps tradition will often object to the use of the term "former Marine" or "ex-Marine" because Marines are inculcated with the ethos "Once a Marine, always a Marine". The terms "former" or "ex" refer to something that once was, but is no longer, as Col Wesley L. Fox, USMC (Ret.) states in the welcoming theater video at the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Veteran Marine refers to an individual that completed their service and has received an honorable or general discharge from the service (see Veteran Marine at [1]). Veteran Marines may certainly be addressed "veteran Marines", yet Marines who have retired are commonly called "retired Marines". However, addressing any veteran Marine as "Marine", which they still are, is appropriate. Veteran Marines may be addressed as "Sir" or "Ma'am" out of respect, or, according to the "Commandant's White letters" from Commandant General Gray, by their earned rank.[62]

Martial arts program

In 2001, the Marine Corps initiated an internally-designed martial arts program, called Marine Corps Martial Arts Program (MCMAP). The idea was borrowed from the South Korean Marines, who train in martial arts and who, during the Vietnam War, were widely rumored to all hold black belts. Due to an expectation that urban and police-type peacekeeping missions would become more common in the 21st century, placing Marines in even closer contact with unarmed civilians, MCMAP was implemented to provide Marines with a larger and more versatile set of less-than-lethal options for controlling hostile, but unarmed individuals. It is also a stated aim of the program to instill and maintain the "Warrior Ethos" within Marines.[71]

The Marine Corps Martial Arts program is an eclectic mix of different styles of martial arts melded together, similar in concept to Jeet Kune Do. MCMAP consists of boxing movements, joint locking techniques, opponent weight transfer (Jujutsu), ground grappling (mostly wrestling), bayonet, knife and baton fighting, non-compliance joint manipulations, and blood restriction chokes.

Marines begin MCMAP training in boot camp. There are five levels of MCMAP, signified by the color of a rigger's belt (from the lowest to the highest levels: Tan, Grey, Green, Brown, and Black). A minimum level of achievement is set for each rank level, including officers. Recruits and junior officers must earn a tan belt in initial training before being allowed to graduate. After entering the Fleet Marine Forces (FMF), Marines are allowed to progress further in MCMAP. Tan and Grey belts are considered the foundation of the movements in MCMAP, with succeeding belts building on those basic techniques. When a Marine has been screened by his or her command they can attend the MAI (Green Belt Instructor) course. Again upon successful completion and screening they may be eligible to attend the MAIT (Black Belt Instructor) course. The only belt requirement is that, to attend the MAIT course, a Marine must already be at least a Green belt instructor. The highest level in belts is the black belt, which has six degrees indicated by red stripes to the right of the buckle.[71]

Equipment

Infantry weapons

The basic infantry weapon of the Marine Corps is the M16 assault rifle family, with a majority of Marines being equipped with the M16A2 or M16A4 service rifles, or more recently the M4 carbine—a compact variant. Suppressive fire is provided by the M249 SAW and M240G machine guns, at the squad and company levels respectively. In addition, indirect fire is provided by the M203 grenade launcher in fireteams, M224 60 mm mortar in companies, and M252 81 mm mortar in battalions. The M2 .50 caliber heavy machine gun and MK19 automatic grenade launcher (40 mm) are available for use by dismounted infantry, though they are more commonly vehicle-mounted. Precision fire is provided by the USMC Designated Marksman Rifle (DMR) and M40A3 sniper rifle.[72]

The Marine Corps utilizes a variety of direct-fire rockets and missiles to provide infantry with an offensive and defensive anti-armor capability. The SMAW and AT4 are unguided rockets that can destroy armor and fixed defenses (e.g. bunkers) at ranges up to 500 meters. The Predator SRAW, FGM-148 Javelin and BGM-71 TOW are anti-tank guided missiles. All three can utilize top-attack profiles to avoid heavy frontal armor. The Predator is a short-range fire-and-forget weapon; the Javelin and TOW are heavier missiles effective past 2,000 meters that give infantry an offensive capability against armor.[73]

Ground vehicles

The Corps operates the same High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle (HMMWV) and M1A1 Abrams Main Battle Tank as the U.S. Army. However, for its specific needs, the Corps uses a number of unique vehicles. The LAV 25 is a dedicated wheeled armored personnel carrier used to provide strategic mobility.[74] Amphibious capability is provided by the AAV-7A1 Amphibious Assault Vehicle, an armored tractor that doubles as an armored personnel carrier. Somewhat dated, it will shortly be replaced by the Expeditionary Fighting Vehicle, a markedly faster tractor that incorporates superior armor and weaponry. The threat of land mines and improvised explosive devices in Iraq and Afghanistan has also seen the Corps begin purchasing Cougar and Buffalo heavy armored vehicles that can better withstand the effects of these weapons as part of the Mine Resistant Ambush Protected vehicle program.[75] The Marine Corps has ordered 1200 International MaxxPro MRAP vehicles for delivery by February 2008, though some of these vehicles will probably be used by other branches of the Armed Forces. The Marine Corps hopes to use MRAP vehicles to replace all HMMWVs on patrol "outside the wire" in Iraq.[76]

Prior to 2005, the Marines operated exclusively tube artillery—the M198 155 mm howitzer, now being replaced by the M777 155 mm howitzer. In 2005, the Corps expanded its artillery composition to include the High Mobility Artillery rocket system (HIMARS), a truck-mounted rocket artillery system. Both are capable of firing guided munitions.[77]

Aircraft

The organic aviation capability of the Marine Corps is essential to its mission. The Corps operates both rotary-wing and fixed-wing aircraft mainly to provide transport and close air support to its ground forces. However, other aircraft types are also used in a variety of support and special-purpose roles.

The Marine light attack helicopter squadrons (HMLA) are composite squadrons of AH-1W SuperCobras and UH-1N Hueys, as the airframes have over 80% commonality. These provide light-attack and light transport capabilities.[78] Marine medium helicopter (HMM) squadrons fly the CH-46E Sea Knight and CH-53D Sea Stallion medium-lift transport helicopters. They are converting to the V-22 Osprey, a tilt-rotor aircraft with superior range and speed, and are being re-named as "Marine medium tilt-rotor" (VMMT) squadrons. Marine heavy helicopter (HMH) squadrons fly the CH-53E Super Stallion helicopter for heavy-lift missions. These will eventually be replaced with the upgraded CH-53K, currently under development.[79]

Marine attack squadrons (VMA) fly the AV-8B Harrier II; while Marine Fighter-Attack (VMFA) and Marine (All Weather) Fighter-Attack (VMFA(AW)) squadrons, respectively fly both the single-seat and dual-seat versions of the F/A-18 Hornet strike-fighter aircraft. The AV-8B Harrier II is a VTOL aircraft that can operate from amphibious assault ships, land air bases and short, expeditionary airfields. The F/A-18 can only be flown from land or aircraft carriers. Both are slated to be replaced by the STOVL version of the F-35 Lightning II (the F-35B).[80]

In addition, the Corps operates its own organic electronic warfare (EW) and aerial refueling assets in the form of the EA-6B Prowler and KC-130 Hercules. In Marine transport refuelling (VMGR) squadrons, the Hercules doubles as a ground refueller and tactical-airlift transport aircraft. Serving in Marine Tactical Electronic Warfare (VMAQ) Squadrons, the Prowler is the only active tactical electronic warfare aircraft left in the U.S. inventory. It has been labeled a "national asset" and is frequently borrowed to assist in any American combat action, not just Marine operations.[81] Since the retirement of the US Air Force's own EW aircraft, the EF-111 Raven; Marine Corps Prowlers, along with those of the US Navy, also provide electronic warfare support to US Air Force aircraft.

The Marines also operate two Marine UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) squadrons (VMU), with the RQ-2 Pioneer UAV for tactical reconnaissance.[82]

Marine Fighter Training Squadron 401 (VMFT-401), operates F-5E, F-5F and F-5N Tiger II aircraft in support of air combat adversary (aggressor) training. Marine helicopter squadron one (HMX-1) operates the VH-3D Sea King medium-lift and VH-60N Nighthawk light-lift helicopters in the VIP transport role. A single Marine Corps C-130 Hercules aircraft "Fat Albert" is used to support the US Navy's flight demonstration team, the "Blue Angels".

Marine bases and stations

The Marine Corps operates 15 major bases, 10 of which host operating forces.[83] Marine Corps bases are concentrated around the location of the Marine Expeditionary Forces (MEF), though reserve units are scattered throughout the United States. The principal bases are Camp Pendleton on the West Coast, home to I MEF; Camp Lejeune on the East Coast, home to II MEF, and Camp Butler in Okinawa, Japan, home to III MEF.

Other important bases are the homes to Marine training commands. Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center Twentynine Palms in California is the Marine Corps' largest base. Marine Corps Base Quantico in Virginia is home to Marine Corps Combat Development Command. It is considered the "Crossroads of the Marine Corps"[84] as most Marines will attend school at Quantico at some point—it is home to initial officer training and the Marine Corps University, which contains the career schools Staff Non-Commissioned Officers Academy, Marine Corps War College (MCWAR), School of Advanced Warfighting (SAW), Command and Staff College (CSC), The School of MAGTF Logistics (SOML)Expeditionary Warfare School (EWS)and Officer Candidate School (OCS) , as well as a variety of other leadership and education programs. There is also Guantanamo Bay, which is located in Cuba and serves as a military prison and a hub for ground forces.[85]

Famous Marines

Many famous Americans, as well as CEOs of many Fortune 500 Companies, have served in the Marine Corps. Tom Monaghan, the founder of Domino's Pizza, is a Marine. In music, John Philip Sousa joined the Marines and became the band's conductor while serving for 13 years. In politics, Senator Zell Miller, pundit James Carville, Secretary of the Navy and U.S. Senator Jim Webb and military analysts Anthony Zinni, Joseph Hoar and Bernard E. Trainor are Marines. Baseball Hall of Famers Tom Seaver, Ted Williams, Rod Carew, Roberto Clemente, Eddie Collins, and Bill Veeck all served in the Marines. Professional boxers Leon and Michael Spinks are both Marines, as are former heavyweight champions Gene Tunney & Ken Norton. Six astronauts, including Senator John Glenn, Charles F. Bolden, Jr. and Fred Haise, are Marine aviators. Several have succeeded in the entertainment industry, including actors Steve McQueen, Don Adams, Gene Hackman, Harvey Keitel, Lee Marvin and Drew Carey; and reggae musician Orville Burrell (Shaggy). R. Lee Ermey and comedian Jonathan Winters were both drill instructors prior to their renown. In addition, many films feature the U.S. Marine Corps.[13]

See also

- Marine (military)

- Radio Reconnaissance Platoon

- United States Marine Corps Women's Reserve

- Commandant's Own Drum and Bugle Corps

- General Orders for Sentries

- Five paragraph order

- Rifleman's Creed

- Iron Mike

References

- ^ a b Gen. Charles C. Krulak (1996). "Operational Maneuver from the Sea" (PDF). Headquarters Marine Corps.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Warren, James A. (2005). American Spartans: The U.S. Marines: A Combat History From Iwo Jima to Iraq. New York: Free Press, Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-87284-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Hough, Col Frank O. (USMCR); Ludwig, Maj Verle E. (USMC), and Henry I. Shaw, Jr. "Part I, Chapter 2: Evolution of Modern Amphibious Warfare, 1920-1941". Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal. History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, Volume I. Historical Branch, HQMC, United States Marine Corsp. Retrieved 2007-06-02.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Garand, George W. and Truman R. Strobridge (1971). "Part II, Chapter 1: The Development of FMFPac". Western Pacific Operations. History of U.S. Marine Corps Operation in World War II, Volume IV. Historical Branch, HQMC, United States Marine Corps. Retrieved 2007-06-02.

- ^

Frank, Benis M and and Henry I. Saw, Jr. (1968). "Part VI, Chapter 1: Amphibious Doctrine in World War II". Victory and Occupation. History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, Volume V. Historical Branch, HQMC, United States Marine Corps. Retrieved 2007-06-02.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ John H. Dalton, Secretary of the Navy; Adm. J. M. Boorda, Chief of Naval Operations; General Carl E Mundy, Commandant, U.S. Marine Corps (November 11, 1994). "Forward...From the Sea". Department of the Navy.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Israeli Defense Forces, CSIS (Page 12)" (PDF). 2006-07-25.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "United State Armed Forces, DOD" (PDF). DOD. 2006-07-25.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e Estes, Kenneth W. (2000). The Marine Officer's Guide, 6th Edition. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-567-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

U.S. Marine Band. "U.S. Marine Band — Our History". USMC.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Marine Barracks, Washington, DC". GlobalSecurity.org.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Marine Security Guard Battalion". GlobalSecurity.org.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e

Lawliss, Chuck (1988). The Marine Book: A Portrait of America's Military Elite. New York: Thames and Hudson.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Milks, Keith A. (May 8 2003). "Ensuring 'Every Marine a Rifleman' is more than just a catch phrase". 22 MEU, USMC.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Lieutenant Colonel R.D. Heinl, Jr., USMC (1947). "Marines in WWII Historical Monograph: The Defense of Wake". Historical Section, Division of Public Information, Headquarters, USMC.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lind, William S. (1985). Maneuver Warfare Handbook. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 0-86531-862-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Chenoweth, USMCR (Ret.), Colonel H. Avery (2005). Semper fi: The Definitive Illustrated History of the U.S. Marines. New York: Main Street. ISBN 1-4027-3099-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ U.S. Congress (11 July 1798). "An Act for Establishing and Organizing a Marine Corps".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e Simmons, Edwin H. (2003). The United States Marines: A History, Fourth Edition. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-790-5.

- ^ U.S. Congress (30 June 1834). "An Act for the Better Organization of the United States Marine Corps".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Moskin, J. Robert (1987). The U.S. Marine Corps Story. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Ellsworth, Harry Allanson (1934). One Hundred Eighty Landings of United States Marines 1800–1934. Washington, D.C.: History and Museums Division, HQ, USMC.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Report on Marine Corps Duplication of Effort between Army and Navy". U.S. Marine Corps. December 17 1932.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help)Contains a very detailed account of almost all the actions of the Continental Marines and USMC until 1932. It is available in scanned TIFF format from the archives of the Marine Corps University. - ^ Flippo, Hyde. "The devil dog legend". About.com.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "History of Marine Corps Aviation — World War One". AcePilots.com.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Ballendorf, Dirk Anthony (1997). Pete Ellis: an amphibious warfare prophet, 1880–1923. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Marines in World War II Commemorative Series". Marine Corps Historical Center.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Marine Corps History". GlobalSecurity.org.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Krulak, Victor H. (1984). First To Fight: An Inside View of the U.S. Marine Corps. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-785-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Chapter 7, The Marines' Push Button 113-119 - ^ Fehrenbach, T.R. (1994). This Kind of War: The Classic Korean War History. Brassey's. ISBN 1-57488-259-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Fast Facts on the Korean War". History Division, U.S. Marine Corps.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Official U.S. Navy figures number the USMC deaths at 13,091. This source provides a number of 14,837. "U.S. Military Casualties in Southeast Asia". The Wall-USA. March 31, 1997.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

"Casualties: U. S. Navy and Marine Corps Personnel Killed and Wounded in Wars, Conflicts, Terrorist Acts, and Other Hostile Incidents". Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy. August 7, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Marines Awarded the Medal of Honor". United States Marine Corps.

- ^ Simmons, 247. Roughly 800,000 Marines served in Vietnam, as opposed to 600,000 in World War II.

- ^ Millet, Alan R. (1991). Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps. New York: Macmillan.

- ^ "The preannounced landing of U.S. Marines was witnessed by millions of U.S. primetime television viewers" (PDF). United States Naval Aviation, 1910–1995. U.S. Navy.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) (PDF file, see 1992, December 9, p. 16. - ^ "Address to Congress". whitehouse. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ a b "CNN Transcript". CNN. Retrieved 2007-04-27. Cite error: The named reference "CNN" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Marines land in Afghanistan". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ^ "Fact Sheet - CJTF-HOA". Combined Joint Task Force - Horn of Africa. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ "USMC.mil - 26th MEU in HOA". United States Marine Corps. Retrieved 2007-04-24.