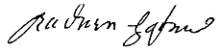

Andreas Hofer

Andreas Hofer (born November 22, 1767 at the Sandhof near St. Leonhard in Passeier in the County of Tyrol ; † February 20, 1810 in Mantua , Kingdom of Italy ) was the host of the “ Am Sand ” inn - hence also known as the Sandwirt . In addition, he was also active as a horse and wine dealer. As the leader of the Tyrolean uprising of 1809 , he is considered a freedom fighter against the Bavarian and French occupation of his homeland. On site, Hofer - especially by the German-speaking population - is often honored with numerous monuments as a folk hero and in a glorifying way as a national hero.

Life

Childhood and youth

Andreas Hofer was born as the male heir longed for by his parents as the fourth child after three sisters. His father Josef was 43 years old at the time of his birth and the owner of the thriving inn "Am Sand" in Passeier . His mother Maria died in 1770 when he was only three years old. He was not treated particularly well by Anna Frick, his father's new wife, with whom he had another daughter. His father died in 1774, and the unfriendly stepmother took over the management of the inn, although she was not very suitable. He attended school, which had only been compulsory for a few years. There he only learned basic arithmetic and writing. Until the end of his life, his written routing slips were based directly on the verbatim speech in the South Tyrolean dialect, without any attention to spelling rules.

One of his sisters married Josef Griener soon afterwards, who had to undertake to continue running the guest and farming business on the Sandhof until Andreas Hofer came of age. The constant disputes between his stepmother and his brother-in-law, who soon owed the property with 1,700 guilders , were probably the main reason why Andreas Hofer was employed by various landlords and also wine merchants for some time before he came of age. During this time he was also in Welschtirol ( Cles in Val di Non ), where he learned Italian, and probably on trips to northern Italy. On these trips he was able to acquire a good knowledge of the country and its people in the wider area.

Tyrolean uprising of 1809

As a result of Austria's defeat in the Third Coalition War and the Peace of Pressburg , Tyrol was under Bavarian rule from 1805/1806. The Bavarians began to implement a series of reforms in their new province of Tyrol, with the disregard of the old Tyrolean military constitution ( Landlibell Emperor Maximilians I from 1511) and the reintroduction of the Josephine church reform causing displeasure ( Minister Montgelas ). Interventions in religious life (prohibition of Christmas mass, processions and pilgrimages, rosary etc.) also led to resistance from the clergy and the population.

The forced drafting of recruits for the Bavarian Army ultimately led to the uprising that began on April 9, 1809 in the Tyrolean capital Innsbruck . If the uprising is mostly understood to this day as a freedom struggle against Bavarian and French foreign rule and their church struggle and recruitment practice, it also showed reactionary, anti-Enlightenment features. For example, Haspinger , a Capuchin priest who opposed the smallpox vaccination introduced by the Bavarian occupation for Tyrol , on the grounds that this should instill “Bavarian thinking” into Tyrolean souls; and Hofer forbade all "balls and festivals" after the first victory and ordered by decree that "women" were no longer allowed to " cover their breasts and arms too little and with transparent rags ". Taverns should remain closed during the service. Immediately after the first battle on the Bergisel, there were violent riots against the Jewish population of Innsbruck on the part of the insurgents.

Andreas Hofer was elected as supreme commander at the head of the anti-Bavarian movement. On April 11, 1809, he was able to prevail against the Bavarians in a battle near Sterzing . On April 12th, the first battle at Bergisel took place with Andreas Hofer and Martin Teimer at the head of the Tyrolean armed forces. Just two days later, after Teimer's victory near Wildau (also Wilten) over the Bavarian-French Bisson corps, the Austrians and Tyrolean rebels were able to move into Innsbruck. However, the Bavarian and French troops succeeded in regaining control of parts of Tyrol and recaptured Innsbruck. After the Bavarian-French troops prevailed in a bloody battle near Wörgl on May 13th, the second battle at Bergisel took place from May 25th to 29th, with the Bavarian troops having to retreat defeated into the Lower Inn Valley on May 29th . The Znojmo armistice followed with a renewed occupation of Tyrol by Napoleonic troops. The call to the Landsturm was followed by another victory of the rebels on August 13th: 15,000 Bavarian, Saxon and French soldiers under the leadership of Marshal Lefebvre faced an equally large Tyrolean rifle contingent under Andreas Hofer (third battle on Bergisel).

The Peace of Schönbrunn , which remained unconfirmed in Tyrol and was considered treason, motivated Hofer again to rebel, which ended on November 1, 1809 with the defeat of the Tyroleans on the Bergisel . Another call for resistance on November 11th had little effect.

Capture and execution

As the leader of the insurrection movement, Hofer had resisted to the very end and had become an outlaw. But he could not make up his mind to flee to Austria; After the final collapse of the military resistance, he and his family and his secretary and confidante Kajetan Sweth sought refuge first on the "Kellerlahn" in the Passeier, then on the "Pfandlerhof" and then on the Mähderhütte of the " Pfandleralm " ( alpine pasture of the Prantacher Hof opposite St. Martin in Passeier ). His escape ended there on January 28, 1810, and he was captured by French occupation soldiers who had found out about his whereabouts from the Tyrolean Franz Raffl for 1,500 guilders. He was then brought first to Bolzano and then to Mantua , the headquarters of the French viceroy of Italy, Eugène Beauharnais , who was responsible for the southern part of Tyrol , and was arrested there on February 5, 1810 in the Porta Molina military prison .

Beauharnais initially wanted to spare Hofer's life, but the French Emperor Napoleon ordered the immediate trial and execution . The French court martial that met as a result - its public defender, the Italian lawyer Jakob Bassevi from Mantua, tried in vain to be spared - after a brief trial on February 19, 1810, Andreas Hofer was sentenced to death . This was carried out the following day by firing squad. After the death sentence had been read, the shots rang out and Hofer fell to his knees, a second volley hit his face and he collapsed, but was still alive. Thereupon Michel Eiffes from Luxembourg approached him and gave him the coup de grace by shooting him in the left temple. Eiffes was accepted into the French army in 1800 , although he wanted to evade this compulsory obligation. He died 35 years after Hofer's execution at the age of 66 and was a highly respected war veteran in his Luxembourg hometown of Befort, where he worked as an innkeeper and mayor.

Hofer was first buried in Mantua in the parish garden of the citadel . Tyrolean Kaiserjäger under the leadership of Georg Hauger exhumed his bones on January 9, 1823 while marching back from Naples to Tyrol and brought them first to Trento , then to Bolzano. During the court martial investigation into the case, which lasted until August 1823, Hofer's remains came to Innsbruck, where they were temporarily stored in a box in the Servite monastery until 1834 and were ceremonially transferred to the court church in the same year . His tomb was made according to a design by the Tyrolean painter Johann Martin Schermer .

Hofer was originally the commander of the Passeirer Schützen and took the rank of major , which is why there was no higher rank among the standing riflemen who were later called up , as no one was supposed to be above Andreas Hofer.

Nobility rise

The nobility diploma , which established the ennoblement of Andreas Hofer, was only issued to Hofer's son, Johann Hofer von Passeyr , on January 26, 1818 . The elevation of Andreas Hofer to the nobility took place on May 15, 1809, through a hand-held ticket issued by Emperor Franz to Count Ugarte from Niederhollabrunn . However, since the court decree could not be sent to Tyrol because of the war events, the question remains whether Andreas Hofer even became aware of his ennoblement. The Hofer von Passeyr family died out in Vienna in 1921 with Leopold Hofer Edlen von Passeyr, a great-grandson of Andreas Hofer. Leopold Hofer is buried in the Grinzing cemetery.

Versions of Andreas Hofer's last words

Hofer's last words are said to have been "Franzl, Franzl, I owe that to you!" But it is also reported that Hofer exclaimed after the first firing volley had only injured him: “French! Oh, how bad you shoot! "

There is no historical evidence whatsoever for the origin of this rumor, which emphasizes the fighting power of the own Tyrolean riflemen ; however, these words are also part of the Andreas Hofer song (Tyrolean national anthem).

reception

Andreas Hofer as a folk hero

Andreas Hofer is considered a popular hero among the Tyrolean population, and his commitment is honored with a number of monuments; every year on February 20th he is celebrated as a fatherland hero. Critical voices against the political mythologization of the uprising, which also resulted from “religious fundamentalism” (reclaiming the abolished monopoly of faith of the Catholic Church) were also occasionally voiced.

The Sacred Heart Festival , which is celebrated annually in all of Tyrol, is closely related to the battles of Napoleonic times : When Tyrol was threatened by French troops in 1796, the Tyrolean Parliament vowed to celebrate the Sacred Heart Festival every year still happens today with church services, processions and mountain fires.

The Andreas Hofer song (“To Mantua in Gang”) is the national anthem of the Austrian state of Tyrol . In what is now the autonomous Italian province of South Tyrol , calls for the song to also be declared a national anthem have so far been rejected by politicians. The text comes from the poet Julius Mosen, who was born in Marieney in the Saxon Vogtland in 1803 and died in Oldenburg in 1867 . The students of the Julius-Mosen-Gymnasium in Oelsnitz (Vogtland) , named after him, cultivate the connection to Andreas Hofer through trips to South Tyrol and performances by music and singing groups in Bolzano . Conversely, Tyrolean rifle squads take part in events in Mosen's homeland.

The highlight of the Andreas Hofer Memorial Year took place on September 20, 2009 in Innsbruck. Around 28,000 members of traditional associations took part in a parade, who parade past the official gallery for almost five hours, in which the Federal President , Federal Chancellor , the governors of the three historic Tyrolean regions and other top politicians were. In addition, around 70,000 spectators took part in the parade. The controversial crown of thorns, which is a symbol of the oppression of the South Tyroleans by Italy, was carried along with the procession, but was symbolically defused by roses. South Tyrolean rifle companies carried banners with texts like “Los von Rom!” And “Self-determination for South Tyrol” in front of them.

In the Sandhof in St. Leonhard as part of the MuseumPasseier , Hofer's life and work has been examined from different perspectives - including critical ones - since 2009. At the beginning of the museum tour, the controversial term hero is questioned, for which there is no generally applicable definition.

Several chapels were dedicated in honor of the fighter, see Andreas Hofer Chapel .

Imperial honor

Due to the imperial resolution of Franz Joseph I of February 28, 1863, Andreas Hofer was added to the list of the “most famous warlords and generals of Austria worthy of perpetual emulation”, in whose honor and memory there was also a life-size statue in the general hall of that time The newly established Imperial and Royal Court Weapons Museum (today: Heeresgeschichtliches Museum Wien ) was built. The statue was created in 1873 from Carrara marble by the sculptor Johann Preleuthner and was dedicated by Emperor Franz Joseph himself.

Andreas Hofer during National Socialism

In particular, the option , which was described as an option between the fascist dictatorships of Italy and Germany between 1939 and 1943, was for German-speaking South Tyroleans and Ladins to leave their South Tyrolean homeland and exercise the option for Germany ( Optanten ) or to remain in South Tyrol ( Dableiber ) not really compatible with the life of the South Tyrolean Andreas Hofer from St. Leonhard in Passeier. So the South Tyrolean NS resistance group was formed as the Andreas Hofer Bund with reference to his work . The resistance of the Andreas Hofer Association against National Socialism was one of the prerequisites for the South Tyrolean People's Party (SVP), founded in May 1945, to be recognized by Italy as the legal political representative of the German and Ladin speaking South Tyroleans.

Already because of the option, an instrumentalization of Andreas Hofer, who of course had also fought against a Bavarian occupation of his homeland, by the NSDAP for their Greater German purposes was almost impossible. The tradition cultivated in Vienna of commemorating Andreas Hofer on the day of his death in St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna was interrupted by the National Socialists in 1938; perhaps also because for the referendum planned by Schuschnigg for March 1938 the "Mander, s'ischt Zeit" ( men, it is time ), known as the Hofer quote , was used and printed on posters.

After 1945, Andreas Hofer was built up as a hero of the Tyroleans and Austrians who were loyal to their homeland, especially as the patron saint to preserve the unity of Tyrol. In 1956, the commemoration in St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna was resumed.

Hofer is reportedly also great grandfather of the same name Tyrolean resistance fighter against the Nazi Andreas Hofer , who in 1944 as a member of the resistance group to Henry Maier and Walter Caldonazzi , sentenced to death and in April 1945 by SS men in the prison of Stein an der Donau shot was .

In literature and media

As early as 1827, Karl Immermann wrote Das Trauerspiel in Tyrol , which was soon banned by Austrian censors. In 1899, the native author Franz Kranewitter devoted himself to the Tyrolean past: the drama about Andreas Hofer under the title Andre Hofer was written. In 1968 this play was performed by the South Tyrolean Unterland open-air theater under the direction of Luis Walter. Later it was u. a. performed by the Tiroler Volksschauspiele in Telfs in 1984 under the direction of Klaus Rohrmoser . In 1959, the year of the 150th anniversary of the Tyrolean uprising of 1809, an Andreas Hofer comic by Hans Seiwer and Georg Trevisan was published.

In 1984 the Andreas Hofer myth received a new impetus through the celebration of the 175th anniversary. In particular, the public conflict over the crown of thorns , a metal crown several meters in diameter that was carried by the Tyrolean riflemen during the parade, was formative for the country. The crown of thorns was carried from the Brenner to Innsbruck and should remain there. The discussion about the crown of thorns was one of the milestones for the creation of the list for a different Tyrol , from which the Tyrolean Greens would ultimately emerge. The crown of thorns is located about 30 kilometers west of Innsbruck in the market town of Telfs on the Thöni site .

With his book Des Hofer's new clothes , Siegfried Steinlechner presented a first comprehensive history of the reception of Andreas Hofer in 2000. According to this, Hofer himself should by no means be seen as a national hero and in 1848 was rather ridiculed even in Tyrol. With the rise of the German Nationals in Tyrol, however, he was transfigured into a figure of national resistance. That is why the Andreas Hofer song , with which the death of Hofer is celebrated, also includes the words “all of Germany was in shame and pain”. The National Socialists once again brought Andreas Hofer into play as the defender of Germanness against Italy and France , and Bozen was established as the myth of the “last German city” that Hofer defended.

In 2001 the life story of Andreas Hofer was filmed in the film Andreas Hofer - The Freedom of the Eagle by Xaver Schwarzenberger ; Leading roles: Tobias Moretti (Andreas Hofer), Franz Xaver Kroetz (Joachim Haspinger) and Martina Gedeck (Mariandl).

Andreas Hofer monuments

Andreas Hofer monument in Merano

Andreas Hofer monument in Kufstein

Andreas Hofer Monument , Bergisel, Innsbruck

Debate about the Andreas Hofer Lied (2004)

In 2004, Andreas Hofer again caused broad discussions in Tyrol. To the tune of Andreas Hofer song, there are historically traditional texts different, including social democratic and socialist, for example to the contrary dawn of Heinrich Eildermann . When this song was sung publicly at a party of the SPÖ , Otto Sarnthein , regional chairman of the Tyrolean riflemen, reported it. A state law from 1948 provided for up to four weeks' arrest in the event that a different text was sung to the melody. At a session of the Tyrolean Parliament in November 2004, the legal text was slightly changed.

More Tyrolean freedom fighters

- Josef Speckbacher (1767-1820)

- Peter Mayr (1767-1810)

- Katharina Lanz (1771-1854)

- Martin Teimer von Wildau (1778–1838)

- Giuseppina Negrelli (1790–1842)

other topics

- Hofer von Passeyr , the ennobled descendants of Andreas Hofer

- Andreas-Hofer-Bund , various associations with different objectives

- Andreas-Hofer-Kreuzer , emergency money to finance the Tyrolean struggle for freedom

literature

- Josef Danei: The uprising of the Tyroleans against the Bavarian government in 1809 according to the records of contemporary Josef Daney . On the basis of the first edition by Josef Steiner (1909) revised, completed and provided with notes, an introduction and biographical information. In: Mercedes Blaas (ed.): Schlern writings . tape 328 . Universitätsverlag Wagner, Innsbruck 2005, ISBN 3-7030-0402-9 .

- Humbert Fink : On Mantua in gangs: The life and death of the folk hero Andreas Hofer . Econ , Düsseldorf 1992, ISBN 3-430-12779-3 .

- Michael Forcher : Anno Nine: The freedom struggle of 1809 under Andreas Hofer . Events, backgrounds, aftermath. Haymonverlag, Innsbruck 2008, ISBN 978-3-85218-582-8 .

- Jochen Gasser, Norbert Parschalk: Andreas Hofer - An illustrated story . Tyrol's survey 1809. Edition Raetia, Bozen 2008, ISBN 978-88-7283-334-6 .

- Margot Hamm: The Bavarian integration policy in Tyrol 1806-1814 . In: Series of publications on Bavarian national history . tape 105 . Munich 1996, ISBN 3-406-10498-3 .

- Karl Theodor von Heigel : Hofer, Andreas . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 12, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1880, pp. 559-563.

- Josef Hirn: Tyrol's uprising in 1809 . Schwick, Innsbruck 1909.

- Hans Kramer: Hofer, Andreas. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 9, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-428-00190-7 , p. 378 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Hans Magenschab : Andreas Hofer . Between Napoleon and Kaiser Franz. Graz / Regensburg 1994, ISBN 3-222-11522-2 .

- Farewell to the fight for freedom? Tyrol and “1809” between political reality and transfiguration. In: Brigitte Mazohl-Wallnig, Bernhard Mertelseder (ed.): Schlern writings . tape 346 . Universitätsverlag Wagner, Innsbruck 2009, ISBN 978-3-7030-0453-7 .

- Andreas Oberhofer: The other Hofer . The person behind the myth. In: Schlern writings . tape 347 . Universitätsverlag Wagner, Innsbruck 2009, ISBN 978-3-7030-0454-4 .

- Andreas Oberhofer: Worldview of a "hero" . Andreas Hofer's written legacy. In: Schlern writings . tape 342 . Universitätsverlag Wagner, Innsbruck 2008, ISBN 978-3-7030-0448-3 .

- Karl Paulin: Andreas Hofer and the Tyrolean struggle for freedom 1809 . According to historical sources. Tosa, Vienna 1996, ISBN 3-85001-579-3 .

- Matthias Pfaffenbichler, Schallaburg Kulturbetriebsgeselschaft mbH in cooperation with the KHM (ed.): Napoleon . General, emperor and genius. Exhibition catalog for the Lower Austrian State Exhibition 2009. Schallaburg Kulturbetriebsgesellschaft, Schallaburg 2009.

- Meinrad Pizzinini : Andreas Hofer . His time - his life - his myth. Tyrolia, Innsbruck / Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-7022-2973-3 .

- Andreas Raffeiner, Sven Knoll , Martin Sendor: Andreas Hofer . His legacy - 200 years later. In: Eckhartschriften . tape 194 . Österreichische Landsmannschaft , Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-902350-30-5 .

- Bernhard Sandbichler: Andreas Hofer 1809 . A story of loyalty and betrayal. Tyrolia, Innsbruck / Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-7022-2488-2 .

- Viktor Schemfil: The Tyrolean War of Freedom 1809 . A military historical representation. In: Schlern writings . tape 335 . Universitätsverlag Wagner, Innsbruck 2007, ISBN 978-3-7030-0436-0 .

- Martin P. Schennach: Revolt in the region . On the Tyrolean survey of 1809. In: Publications of the Tyrolean State Archives . tape 16 . Universitätsverlag Wagner, Innsbruck 2009, ISBN 978-3-7030-0462-9 .

- Hans Seiwer; Giorgio Trevisan [Ill.]: The life and death of Andreas Hofer . Historical representation in words and pictures. South Tyrolean Association of War Victims and Front Fighters; Printed by Robert Haller, Meran 1959.

- Siegfried Steinlechner: The Hofer's new clothes . About the state-supporting function of myths. Studienverlag, Innsbruck / Vienna / Munich 2000, ISBN 3-7065-1397-8 .

- Ilse Wolfram: 200 years of folk hero Andreas Hofer on stage and in film . In: Theater Studies . tape 16 . Herbert Utz Verlag , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-8316-0932-1 .

Movies

- Andreas Hofer (1909): silent film, director: Rudolf Biebrach

- Tirol in Waffen (1914): Silent film with Rudolf Biebrach as Hofer, director: Carl Froelich

- Andreas Hofer (1929): silent film, actor a. a .: Fritz Greiner as Andreas Hofer, Maly Delschaft as Anna Hofer, director: Hans Prechtl

- The Rebel (1932): a film by Luis Trenker

- Der Judas von Tirol (1933): Director: Franz Osten

- Andrè Hofer (1974): TV play based on Franz Kranewitter, directed by Luis Walter

- Der Judas von Tirol (1978): TV play based on Karl Schönherr, directed by Luis Walter

- Andreas Hofer - The Freedom of the Eagle (2002): Actor a. a .: Tobias Moretti as Andreas Hofer, Franz Xaver Kroetz as Feldpater Joachim Haspinger, director: Xaver Schwarzenberger

- Andreas Hofer, Rebel Against Napoleon (2009): Documentary by Bernhard Graf , ORF

- Andreas Hofer's last trip (2009): Documentation (28 min.) By Franz J. Haller and Ludwig Walther Regele (interviews: Roberto Sarzi and Meinrad Pizzinini); Rai Sender Bozen , Office for Audiovisual Media.

- Bergblut (2010): Actor a. a .: Klaus Gurschler as Andreas Hofer, Verena Buratti as Anna Hofer, director: Philipp J. Pamer

comics

- Andreas Hofer. A life for Tyrol , an adventure in world history. The interesting youth magazine, No. 34 (Walter Lehning Verlag, Hanover), undated [approx. 1955].

Web links

- Literature by and about Andreas Hofer in the catalog of the German National Library

- Extensive documentation about Andreas Hofer can be found on tell.at

- 2009 commemorative year "history meets future"

- Insorgenza Tirolese (Italian; with many pictures)

- Andreas Hofer at EPOCHE NAPOLEON

- MuseumPasseier - Andreas Hofer

- Entry on Anna Hofer, the forgotten woman in the Austria Forum (in the collection of essays)

- "Tirol in Waffen" (1913/1914) , the first feature film about Andreas Hofer, on filmportal.de

- ORF Tirol: "Andreas Hofer: Divine Warrior in Lederhosen"

- Edda Dammmüller: February 20th, 1810 - Anniversary of the death of Andreas Hofer WDR ZeitZeichen on February 20th, 2020 (podcast)

Individual evidence

- ^ Hans Magenschab: Andreas Hofer. Between Napoleon and Emperor Franz . Graz / Regensburg 1994, ISBN 3-222-11522-2 , p. 41

- ↑ Gastrointestinal, pp. 43-44

- ↑ Gastric scrape, p. 48

- ^ Tyroleans and Vorarlbergers plunder the Allgäu . ( Memento from June 20, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) In: Allgäuer Zeitung , December 14, 2009

- ↑ Steinlechner: Des Hofer's new clothes , pp. 30–32.

- ↑ a b Fear of a special role , in ORF online, on April 12, 2009

- ↑ Laurence Cole, in: Datum 5/2008, pp. 56f.

- ↑ In the case of the riflemen, officers were appointed by election.

- ^ The drawing of the dungeon at Mantua, ... , p. XXXVII, accessed on August 19, 2014

- ↑ Joseph Ritter von Wertheimer: The Jews in Austria. From the standpoint of history, law, and the state's advantage. Three volumes. Mayer and Wigand: Leipzig 1842, 253 p. Limited preview in the Google book search, p. 259 and 96

- ↑ Upper Austria News from February 27, 2009

- ↑ Little Chronicle. (...) Hofer's bones. In: Neue Freie Presse , Morgenblatt, No. 16343/1910, February 20, 1910, p. 11, center right. (Online at ANNO ). .

- ^ Johann Jakob Staffler : Tyrol and Vorarlberg, topographical with historical remarks , Volume 1, Felician Rauch, Innsbruck 1841, p. 272, limited preview in the Google book search

- ^ "Andreas Hofer's family", Austria. Bundesverlag, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ His legal name was Leopold Hofer, since there had been no nobility in Austria since 1919 and thus no more titles of nobility.

- ↑ Hedwig Abraham: Graves Grinzinger Friedhof Hofer, Leopold, Edler von Passeyr. Art and culture in Vienna, accessed on February 15, 2019 .

- ↑ Almost 100,000 at the Tyrolean pageant . In: ORF . September 20, 2009

- ↑ Innsbruck: The controversial move was peaceful ( Memento from September 28, 2009 in the Internet Archive ). In: The press . September 20, 2009.

- ↑ Johann Christoph Allmayer-Beck : The Army History Museum Vienna. The museum and its representative rooms. Kiesel Verlag, Salzburg 1981, ISBN 3-7023-0113-5 , p. 33 f.

- ^ The "Anschluss" of Austria 1938 , Deutsches Historisches Museum , October 15, 2015, viewed on July 2, 2018

-

^ Hans Matscher: The Meraner Andreas Hofer Monument . In: haben.at. 2008, accessed on March 18, 2011.

An Andreas Hofer memorial in Merano. In: Der Alpenfreund. Illustrated tourist magazine for the Alpine region , issue 6/1896, (VI. Year), p. 63, bottom left. (Online at ANNO ). - ↑ OBV .

- ↑ Online version

- ↑ a b studiowalter.it

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hofer, Andreas |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Hofer, Andreas Nikolaus (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Tyrolean freedom fighter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 22, 1767 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | St. Leonhard in Passeier , Tyrol |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 20, 1810 |

| Place of death | Mantua , Italy |