Serious plaster

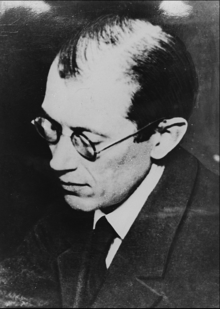

Ernst Raimund Hermann Putz (born January 20, 1896 on the Sinntalhof near Brückenau in Lower Franconia ; † September 12, 1933 in the Berlin-Moabit remand prison ) was a co-founder of a reform-educational rural education home , chairman of an agricultural interest group, an initially independent politician , from mid-1926 a communist politician , Editor of a partisan periodical and the youngest member of the Reichstag at the time . In reference to a medieval military leader of the German Peasant War , he was referred to as " Florian Geyer der Rhön ".

family

Ernst Putz was the second of five children of the sculptor, officer, hostel operator and part-time farmer Sebastian Putz (1867–1937) and his wife Amelie Putz (1868–1918), née Moritz. Both were strictly Catholic. The couple who had married on October 12, 1893 later operation, a thriving boarding house ( pension ), which from the neighboring Staatsbad benefited. The Sinntalhof , founded in 1821, and the lands were brought in by Amelie Putz, who came from a long-established family. When the farm was badly affected by a cyclone in 1910 , the couple built the New Sinntalhof from 1911 , in which the hostel opened in 1912, which became the main source of income for the family.

Ernst Putz, who is said to have been critically ill in his early childhood, had four siblings, the elder Sophie (1894-1923), the younger brother Josef (1897-1914) and the two younger sisters Elisabeth (* 1900) and Charlotte (1903 -1960). Despite their parents' disapproval, all children are said to have left the Catholic Church during their youth. One month after the November pogroms in 1938, however, Charlotte was accepted back into the Catholic Church.

School time as a defining factor

Between 1902 and 1905 Putz attended elementary school in Brückenau, then until 1909 the former Jesuit humanistic grammar school in Pfaffengasse in Aschaffenburg and then until 1912 the royal district high school in Würzburg, where he worked closely with Max "Maxl" Krug (1897-1918 ) made friends. There, however, as a 15-year-old, he was sexually abused by his religion teacher, whom Putz had greatly admired, which he was said to have never got over, as his sister Charlotte reported in 1958.

Possibly this was one reason for his early exit from the church and his move to a country house of education , because he could have taken his school leaving examination in Würzburg. His school there was gradually expanded from a secondary school by three more grades to an upper secondary school between 1907 and 1910 and expanded like a grammar school .

Through the children of a German-Japanese family who were quartered in the Sinntalhof hostel during the summer holidays of 1911 , Ernst Putz learned about a boarding school that interested him straight away. Herta Fumi Ohly (* 1898) and her younger brother Waldemar “Waldi” Hazama Ohly (* 1900) had a lot to report from there: “About inner freedom, music, morning speech and people. A great longing came over me. The school's annual reports - they're all in my bookcase to the right of my desk - I read feverishly. I secretly prepared a hike to the foundation festival in 1913. "

His parents made strong objections to the reform pedagogical Free School Community of Wickersdorf near Saalfeld in the Thuringian Forest , founded by Rudolf Aeschlimann , Paul Geheeb , August Halm , Martin Luserke and Gustav Wyneken and led by Luserke at the time , a non-denominational and thus possibly godless one from theirs Perspective very expensive school camp. Luserke pointed out that Ernst would have to repeat half of the upper secondary school (OII; grade 11) again and would lose half a year as a result. The reason for this is the organizational and didactic difference between the private country school home and the upper secondary school previously attended. The promise of a vacancy sent by Luserke by telegram , the youthful enthusiasm of her eldest son and a clarifying parent-son conversation eventually led to a placet.

“Father and mother were against it, mainly because of a religious attitude. On the bench up at the edge of the forest, under the hornbeam, I overcame the resistance. I was allowed to go. Painless farewell to Würzburg. Drive over Sonneberg , approaching from the south, Reichmannsdorfer Chaussee - Stern - school yard: Ro Frend [meant: FSG student Roland Friend] was dancing across the yard in a bath sheet when he saw me coming. I was there, in my second home. "

From September 20, 1913 to January 22, 1915 he visited the FSG Wickersdorf . There he befriended Roland “Ro” Friend, Otto Gründler (1894–1961), and Wilhelm “Will” Jerosch (1898–1917) , among others . Putz was part of the comradeship of the "bears" led by Luserke, which was founded in 1906 by Ernst Herdieckerhoff and Luserke. On October 11 and 12, 1913, he and around one hundred other schoolmates took part in the First Free German Youth Day on the Hohe Meißner , while Luserke and Wyneken gave lectures there.

Ernst Putz perceived his impressions in the Thuringian Forest very intensely and was able to express them vividly and almost poetically in words:

“Everything was indescribable. Above all, nature. Take the quiet paths, the great [?] And the panorama, to Ellen Key Square, over the horizon, to Feldherrnhügel and to the Meurablick at different times of the year . When the wind is blowing in winter, everything is deep in the snow, the fir trees in the forest crack and creak and the slates rattle on the walls. Or on a gentle summer night, a full moon over the mountains, filling the valleys with its light and shadow, the brook babbling in the valley, the wind gently rocking the fir trees. In the hot summer through the oak trees, when the sun is shining on it, to the Meurablick, where August Halms burial mound is today. How strongly Mother Nature took me in her arms during these years, I cannot say. My second home, never lost, my soil, my trees, the tall linden trees opposite the manor house, the apple tree meadow, the lake in the valley, the smell of soil, grass, fir tree, stone - oh, you Wickersdorfers , you will know how mine Heart is full of all these glories! "

As a student, Putz was interested in, among other things, the youth culture movement around the school newspaper Der Anfang , which Wyneken was responsible for under press law and which was editorially supervised by George Barbizon and Selig Bernfeld under the motto “Through the youth, for the youth!” . When Bernfeld announced the founding of the Green Wandering Bird and the Green Anchor and called on readers to collaborate, Putz offered in writing in mid-February 1914. In the Grüner Anker , a counseling center for young people, members of parliament, doctors, university lecturers, journalists, lawyers and pedagogues made themselves available free of charge as contact persons for young people seeking advice. Putz applied with the argument: “[...] I'm 18 years old. After spending seven years in boarding schools run by the church and the church, I know how difficult the struggles are that some people have to go through. Since I know that I have already been able to help many younger comrades in religious, sexual and moral difficulties, I believe that I can do this work [...]. ”Putz was also confronted with the issue of homoerotic and homosexual contacts within the FSG Wickersdorf . In February 1914, he corresponded with the school's founder, Wyneken, who originally envisioned the FSG Wickersdorf as the "Order of noble boys and youngsters". Wyneken had gathered a circle of pedophile teachers around him, including Fernand Camille Petit-Pierre (1879-1972) , who also emerged as the author of lyrical homoeroticism under the pseudonym René Lermite .

Ernst Putz was a very active member of the Wickersdorf student committee. On June 21, 1915, he became a foreign member of the school community, which included selected former students and teachers. He also took part in meetings of the school community in the following years. At his suggestion, Luserke applied on September 9, 1918, to intensify the correspondence between the school community and FSG Wickersdorf soldiers .

During his entire war mission, Lieutenant Ernst Putz kept in close contact with FSG Wickersdorf , to which he retired from January 4 to March 16, 1919, in order to regenerate after the war. On January 20, 1919, Putz, together with Horst Horster (1903–1981), Hedda Korsch and Martin Luserke, applied to the public because of increasing property crimes within the country school home in order to be able to combat this undesirable development more effectively in the tough post-war period. Four days later, at his request, the school community decided to strengthen the rights of the student committee. Putz was in a position to be completely absorbed in his devotion to this community, but never lost his ability to criticize and spoke out emphatically.

Around the middle of August 1926, Ernst Putz, a member of the Reichstag, was on the island of Juist in Luserke's school by the sea to meet this and other teachers he knew from FSG Wickersdorf . At this time Putz corresponded, also from Juist, repeatedly with Friedrich Pustet III (1867-1947) in Regensburg, a publisher of liturgical Catholic writings. Four years earlier, von Pustet had relocated the religious-philosophical dissertation of Ernst Putz's close friend Otto Gründler elsewhere.

After the death of the Wickersdorf music teacher, composer and temporary headmaster August Halm in 1929, Ernst Putz, a member of the Reichstag, was present in the Thuringian Forest: “I sat at Halms grave in the last hours of my stay in Wickersdorf. It was a hot September day and the land below me was clear as autumn. Who wouldn’t want to envy the musician for this piece of earth ”.

In retrospect, Ernst Putz saw his time in Wickersdorf “like a fulfilled life”. For him, the time there was like a “life lived in advance of a future humanity”, with the “spirit of real camaraderie and an unheard-of community spirit”.

During his detention he wrote to his father: “You never understood why I was so attached to Wickersdorf. […] This is how mankind will live later - changing external forms, of course, and a clearer worldview based on the ideas that I have now served for the last 10 years ”.

The last surviving words of Ernst Putz were not about his unfinished political commitment, but were dedicated to his schoolmates, teachers and his second home, to which he felt deeply connected: “[...] how grateful I am to fate for this time. [...] Once again, before I hurry on, I greet you, you mountains around Wickersdorf, forest, scent of fir trees, shadow and light of the valleys, you people who are so closely connected with this area - you, you beautiful life, that I lived there! "

War effort

At the beginning of the war in August 1914 he volunteered - like many patriotically minded - as a volunteer , but in contrast to his father and his one year younger brother, he was postponed due to a weak constitution and therefore initially returned to Wickersdorf. His brother Josef died at the age of 17 as a member of the 2nd company of the Royal Bavarian 17th Infantry Regiment "Orff" located in the fortress Germersheim on November 8, 1914 near Ypres . On March 9, 1915, Putz passed an external high school diploma in Berlin-Lichterfelde in order to qualify for an officer career.

On March 22, 1915, he entered the Kiel Naval School and was then stationed in Flensburg-Mürwik , where there was a torpedo station and a torpedo school that resulted from it. As a lieutenant of the Naval Corps under Ludwig von Schröder was Ernst Putz during the First World War among others in 1915 on the Great torpedo boat SMS S 126 used in the Funkentelegraphieabteilung (FT Div.), In 1917 on the Great battleship SMS Posen under Wilhelm von Krosigk , from spring 1918 at the General Command of the Marine Corps of the Imperial Navy in Bruges . During his deployment on the Western Front he took part in the retreat from Flanders after October 15, 1918 (day of the withdrawal order) , which showed him the war on land and its consequences. In the same year, his mother died at the age of 50. On December 31, 1918, Ernst Putz resigned as a lieutenant in the reserve. He was probably the bearer of the Cross of Honor and Commemoration of the Marine Corps Flanders .

After the end of the war, Putz could not simply finish with what he had experienced and heard. His teacher Siegfried Wilhelm Paul Krebs (1882–1915), who had received his doctorate in Heidelberg in 1909 , was a philologist, writer and art teacher, had been the first war volunteer from Wickersdorf, deployed in France, and was then quickly the first to die at the FSG Wickersdorf was to be lamented. I.a. Putz remembers him in his notes with sadness.

His close schoolmate "Maxl", Max Krug (1897–1918) from Münnerstadt in Lower Franconia , who had attended the Royal District High School in Würzburg with him , was last deployed as a lieutenant in the Aviator Replacement Department (FEA) 3 Darmstadt-Griesheim after a very serious front-line injury and after their relocation to Gotha on April 6, 1918 died in a plane crash there. He may have been transferred to Neustadt an der Saale . In his notes, Putz recalls Maxl, who is characterized as a “funny boy”.

His close schoolmate "Will" from Wickersdorf, the Lisbon- born Wilhelm Jerosch (1898–1917), son of a Hamburg merchant living there, was a member of the 4th Army under Friedrich Sixt von Armin on October 9, 1917 during the Third Ypres Battle near Geluwe killed in heavy defensive battles against British troops.

Before starting his studies, Putz set out on the arduous journey to Belgium, especially in the immediate post-war period, and through the completely devastated landscapes and completely destroyed villages of Flanders, in order to look for his final resting place.

“In the bruised fields of Gheluwell, on the last lane of the road to Zandnorde, I looked for your grave, good boy. But it was no longer to be found, you too are resting - who knows where? "

Note: He meant the West Flanders places Gheluvelt and Zandvoorde east of Ypres .

Studies and drop-out

On June 3, 1918, he enrolled for the summer semester of 1918 in the philosophy department at the Alma Mater Jenensis in Jena under the Nobel Prize for Literature Rudolf Eucken , with whom Luserke had also studied. However, plaster was still “in the field”, as can be seen from the printed student directories. From 1924 Putz himself had truthfully entered in the Reichstag handbook that he had been at the front from 1915 to 1918. From the summer semester of 1919, Putz actually began studying philosophy, which he nominally continued in the winter semester of 1920/21, but was struck off the student lists on January 4, 1921, because he was probably already without Jena in the late summer of 1920 Graduated to found his country school home on the Sinntalhof . Assuming constant attendance, he could study for a maximum of three and a half semesters.

Project reform pedagogical country school home

From the autumn of 1919 to the spring of 1920, Ernst Putz had the Free School and Work Community , which had moved from Auerbach in southern Hesse, after a brief interlude , to act on the Neuer Sinntalhof in order to guarantee them temporary accommodation. These included the former Wickersdorf piano teacher Käthe Conrad (* 1893), Bernhard Hell , Bernhard Uffrecht and Gustav Wyneken's sister Elisabeth Wyneken (1876–1959), known as "Aunt Lies". At the same time, Putz made it possible for various groups of the (bourgeois) youth movement ( Bündische Jugend ) to hold conferences on the Sinntalhof . In 1920 Putz took over the family's Sinntalhof . The Free School and Work Community of Uffrechts moved to Dreilinden in Brandenburg until Easter 1920 .

Probably because of this phase of a school project in its founding phase, Ernst Putz applied to the Bavarian state government in August 1920 to open his own country school home, which was approved in October 1920. Together with the reform pedagogue Max Bondy and his wife Gertrud Bondy (1889–1977), Putz opened the Free School and Work Community Sinntalhof on the New Sinntalhof , a country education home with initially four students. In the following year there were 14 students, in the school year 1922/23 there were 29. Among them was Walter Georg Kühne , who moved to the FSG Wickersdorf after the school closed and from there in 1925 to the school by the sea on the North Sea island of Juist . Putz and Kühne remained friends for life.

Since neither Putz nor Bondy had a completed teacher training and Putz did not complete it afterwards, contrary to his assurance to the Bavarian Ministry of Culture, the teacher Jakob Stahl nominally took over the pedagogical school management of the Free School and Work Community Sinntalhof . Bondy was the commercial manager and Putz was the technical manager. Jürgen Alexander Justus Diederichs (1901–1976), who was a student at the FSG Wickersdorf between 1913 and 1919, took on the horticultural and handicraft lessons . This was the son of the Jena publisher Eugen Diederichs , who pulled strings in the background at FSG Wickersdorf and later was a sponsor of the Schule am Meer . Eugen Diederichs visited the Sinntalhof during a trip around Whitsun 1921. Bondy's only book on pedagogy consisted of the lectures he had given at the Neuer Sinntalhof. It was published by Diederichs Verlag in 1922.

The joint school project of the Bondys and Putz failed due to irreconcilable differences between the two partners in 1923, due to a lawsuit brought by Bondy against Putz, which raised the issue of the management function of their jointly founded school community. Both viewed themselves as headmasters. Since the dispute could not be resolved and Bondy refused to continue joint school management with Putz, Putz informed the school authorities and parents about it and closed the educational facility on the Neuer Sinntalhof in order to keep the damage to the students as low as possible. In his letter to the parents, he recommended other reform educational country school homes, including first and foremost the FSG Wickersdorf , but also the Free School and Work Community , the Hochwaldhausen Mountain School , the Landschulheim am Solling and the Odenwald School . Bondy then turned to the newly founded by him Schulgemeinde Gandersheim in Lower Saxony Gandersheim to; Putz discovered politics.

politicization

Horst Horster, Ernst Putz and Paul Reiner were politicized by Hedda Korsch and Karl Korsch . Horster was in Wickersdorf between April 1913 and March 1920 in the comradeship of Hedda Korsch. He then studied at the Staatliche Kunstgewerbeschule in Berlin and between 1923 and 1926 was a handicraft teacher at FSG Wickersdorf . He later became friends with Bertolt Brecht . Immediately after Putz's death, Horster and his family emigrated to Denmark on the urgent advice of Hedda and Karl Korsch, where he later became well known as a puppet player and worked as a silversmith. Paul Reiner had graduated from high school in Wickersdorf and was a teacher there after studying and doing his doctorate . Horster and Reiner were among Karl Korsch's closest employees. In a first conversation that Hedda Korsch had with Ernst Putz in May 1923 about scientific socialism, he retrospectively viewed his Free School and Work Community Sinntalhof in 1933 as "piecemeal", as an "island of the blessed". Without a struggle one cannot “create a new world”.

Political commitment

In the winter of 1923/24, Putz became aware of many suicides by farmers. In 1924 he was one of the founding members of the with the support of the Communist Party launched a freelance German farmers (BsL) , over which he presided from May 1924 to 1933. Members of the BsL were, for example, the photographer Kurt Beck , Hermann Bischoff , Richard Schneider and Richard Zimmermann , who belonged to the Association of Workers' Photographers in Germany (VdAFD) . BsL and VdAFD were preliminary organizations of the KPD, which were supposed to generate members in (mainly rural) regions in which the KPD was underrepresented.

Putz invited to the Sinntalhof on August 31, 1924 , where more than one hundred small and medium-sized farmers, representatives of 28 communities, KPD employees of the Land department from Berlin and KPD state parliament members from Bavaria, Hesse and Thuringia met and one seven points -Plan adopted the emergency call of the Rhön farmers , which was addressed to the Reichstag, state parliaments and members of parliament. On September 14, 1924, Putz convened the first Rhön Farmers' Day in Gersfeld . Attempts by the Bavarian and Prussian authorities to prevent the event by arresting Putz had failed beforehand. Only Putz's correspondence could be confiscated. Uniformed and so-called civil scouts were supposed to intimidate the approximately one hundred delegates of the Rhön Farmers Day . The district administrator arranged that no innkeeper provided them with rooms. The Rhön farmers' day therefore took place on the street and was expanded to include the demand for a special tax from large landowners, large industry, trading and banking groups.

During the second Rhön Farmer's Day on October 12, 1924, Putz announced his Gersfeld demands in front of more than 400 farmers from 40 communities . The catalog of demands included the granting of loans for small farmers, tax breaks, the waiver of rent and a delivery of seeds and fertilizers.

Ernst Putz initially stood as a non-party candidate on the KPD list for the 3rd electoral term of the Reichstag . In December 1924, at the age of 28, he became the youngest member of the Reichstag, of which he was a member until 1933. As a member of parliament, he lived in the section of Passauer Strasse belonging to Berlin-Schöneberg , one of the Jewish centers of Berlin at the time, with an exiled Russian scene, near Tauentzienstrasse and the Kaufhaus des Westens (KaDeWe).

From 1924 Putz is said to have worked in the Land Department of the Central Committee (ZK) of the KPD under Edwin Hoernle and Heinrich Rau . However, Putz was not a party member at that time. Since the autumn of 1925 he was chairman of the Reichsbund der Kleinbauern (from 1927: Reichsbauernbund ). Only in July 1926 did he join the Communist Party of Germany. A call for the Reichstag election from 1928 shows plaster in the middle of a leaflet. In 1931, for example, he was visited by the Berlin-Neukölln Untergauleiter of the Red Young Front (RJ), Herbert Crüger , in the Karl-Liebknecht-Haus on Bülowplatz .

Alongside Hoernle, Ernst Putz was considered the most competent agricultural expert of the Communist Party of Germany. In 1925, 1927 and 1932 he visited the Soviet Union with delegations of German farmers and took part in numerous national and international farmers' congresses. He also acted as the editor of Ernst Thalmann's leaflets on the KPD's peasant aid program, which were written by Bruno von Salomon .

Putz, who cultivated a calm and matter-of-fact style, also enjoyed a reputation beyond the KPD, as he stood up primarily for small farmers, although he owned a medium-sized farm himself. His speeches as a member of the German Reichstag can be found in the printed Reichstag minutes and accessed online ( see section Publications ). In December 1932, the Reichsbauernkomitee near Berlin met legally for the last time, Ernst Putz and Bodo Uhse gave lectures. Uhse, who was still a National Socialist until July 1930, was among other things an employee of Putz and in January 1932 the main speaker at the Reich Farmers' Congress in Berlin. After the power transfer to the Nazis and the banning of the KPD by the adopted on February 28, 1933 Reichstag Fire Decree Putz worked from Frankenheim / Rhön from the ground on.

Functions

- 1924–1933: Chairman of the Association of Working Farmers

- 1924–1933: Secretary of the Land Department in the Central Committee of the KPD

- 1924–1933: Deputy or member of the Reichstag (center right)

- 1924–1933: Editor of the periodical Einiges Volk of the working group of working farmers, tenants and settlers

- Late 1924–1933: Member of the International Farmers' Council of the KPD

- October 1925–1933: Chairman of the Reichsbund der Kleinbauern (from 1927: Reichsbauernbund )

Imprisonment and death

After about five and a half months of illegal activity, he was arrested on July 19, 1933. During the so-called protective custody , Putz wrote a diary that also contains memories and a kind of farewell letter. He was unable to go into detail about his political work because he was forbidden to do so.

“You know that I went my way out of deepest conviction. To this day, nothing has shaken this conviction. No one who means it honestly can go against their conscience. I have often spoken to you, dearest father, that nothing would stop me from going other ways as soon as I were no longer deeply convinced of the correctness of my views. I have discussed, spoken and advised with people from all directions. I studied the Nazi press for months. But all I found was that the doctrine, the books of which are being burned today, was the right one for me and the only one suitable for the salvation of our working German people. I cannot take away anything that I have spoken and written out of my deepest conviction for ten years, you know that I was always confirmed, also by political opponents, that I was objective. "

According to his sister Charlotte, he committed suicide on September 12, 1933 in Moabit Prison . According to her own statements, she was informed of the death of her brother, seven years her senior, on September 12, 1933. Your diary shows this date accordingly several times.

“My brother, who was bound by deep friendship (he had been my best friend since childhood), committed suicide in 1933 in Moabit prison. It was just before the verdict that our old father and us sisters would have lost their homes and wealth. This was probably one of the motives that led to this decision. It was also important for him to protect even more people through his death in prison. I saw him (my brother) in prison after he died. His face was clear and beautiful, his eyes open; it was in no way disfigured, we had him cremated as he had requested in his farewell letter, and we took the urn with us to his farm, which we have kept as home. "

The records written by Ernst Putz in Moabit clearly prove his suicide. Several passages read like a suicide note and explicitly mention the intended suicide. Putz specifically refers to the "chivalrous" behavior of his interrogator named Fischer. According to official records of the prison administration, he died of suicide while in custody at the age of 37. In doing so, he anticipated the threatened clan confinement and was able to preserve the freedom of his family and the Sinntalhof .

“This is my tragedy: I, who have really tried to give my whole life to others, am perishing in the grief that I may have harmed others and good friends who were close to me. Now it seems clear to me that it is best for all parts if I leave. I can no longer help anyone, I can only make amends for a few things through self-sacrifice, it seems to me, whereby I spare other people. I have often thought that suicide was cowardice. In these days, when I am having to deal with this outcome, I see that it is not so. "

The death of Ernst Putz while in custody was not in the interests of the Nazi strategists, as he was intended to be one of the main defendants in the show trial (Reichstag fire trial) against communists ( Georgi Dimitroff , Marinus van der Lubbe , Ernst Torgler and others). In any case, he is a Nazi victim.

Myths and Legends

A politically motivated legend led to the fact that a number of biographical information (study of agricultural sciences, German studies and mathematics, degree as a qualified farmer ...) and above all the myth (myth) formed about the nature of his death (severe abuse, murder) over decades in the media and clouded the secondary scientific literature. There is no primary evidence for these claims. Nevertheless, an at least psychological form of torture is conceivable, since it corresponded to the interrogation methods of other political prisoners at the time.

"My comrades-in-arms, ignorant of the context, will disapprove of my suicide."

The alleged function of his father as a member of the Bavarian People's Parliament after 1918, which is also part of the SED legend for Ernst Putz, is demonstrably wrong. Sebastian Putz is not listed as a member of parliament in the first to fifth electoral terms of the Bavarian State Parliament during the Weimar Republic.

Estate, tombstone and grave site

The handwritten memories with suicide note from Ernst Putz were handed over to the party archives of the SED by his sister Elisabeth Putz-Valtari in 1974 in a typewritten transcription . You are now in the Federal Archives.

Ernst Putz was cremated in 1933 and his urn was buried on the grounds of the Sinntalhof . The grave stone of the Putz family is an inscribed boulder that Sebastian Putz probably worked on himself. The tombstone was found in 2013, exposed and transported to the cemetery in Leimbachstraße in Bad Brückenau. The grave site itself had been abandoned by the son of Putz's sister Elisabeth Putz-Valtari.

Honors (excerpt)

- Between Brückenau and the Staatsbad Brückenau, the former Badstrasse was renamed Ernst-Putz-Strasse in 1946. Putz's birthplace, the Sinntalhof, is also on this street .

- In the GDR, Ernst Putz's work was widely recognized.

- On December 21, 1951 (Stalin's birthday), the Ernst Putz School was opened in Neurüdnitz an der Oder .

- In Schletta , Meißen district, Dresden district, there was an MTS Ernst Putz. Dto. in Zuchau , Magdeburg district.

- During the GDR era there was an LPG called Ernst Putz in Kaltensundheim .

- in Rostock - Marienehe there was an Ernst Putz memorial stone.

- One of the barracks of the National People's Army bore the name of Ernst Putz.

- In Sangerhausen there is an Ernst-Putz-Straße in the Am Bergmann district .

- In Unterweid , Thuringia , the elementary school (1975–1991 high school) bears the name of Ernst Putz.

- In 1988, Army General Heinz Keßler gave a unit of the NVA the name Ernst Putz.

- In Oberweid , Ernst-Putz-Strasse was renamed Kaltenwestheimer Strasse in 1991. A memorial stone was erected in 1984 during the inauguration with the NVA honor guard. Today there is a private memorial plaque within the village.

- Since 1992, one of the 96 memorial plaques in front of the Reichstag in Berlin for members of the Reichstag murdered by the National Socialists has been commemorating Putz.

Publications

- Poor harvest, tax burden - the farmers' distress. The farmers' conference in Gersfeld and its lessons . New Village Publishing House, Berlin 1924.

- Religion, marriage, family. Christian rural people and communists . Self-published, Sinntalhof, Brückenau o. J.

- We farmers don't want war! New Village, Berlin 1927.

- Farmer who do you choose? Internationaler Arbeiter-Verlag, Berlin 1928.

- with Heinrich Kornelius Giesbrecht: Farmer Giesbrecht moves back to Siberia. Experiences of a Mennonite refugee from Russia . Internationaler Arbeiter-Verlag, Berlin 1930.

- Escape from Russia. Who is emigrating? Internationaler Arbeiter-Verlag, Berlin 1930.

- The farmer with the tractor. Collective Farms and State Goods in the Soviet Union . Internationaler Arbeiter-Verlag, Berlin 1930.

- A village in the Caucasus. Accountability report of a collective farm . West German printing workshops, Berlin 1932.

- Christian rural people and communists. Religion, marriage, family . Edited by the Communist Party of Germany. West German printing workshops, Düsseldorf 1932.

- German farmers in Soviet Russia. Twenty German farmers travel through the Soviet Union. Putz, Sinntalhof 1932. Digitized

The speeches of the MP Ernst Putz before the German Reichstag can be found in printed form in the Reichstag protocols (register volumes 396, 429 and 447).

Audio

Political speeches by Ernst Putz were recorded and are preserved on shellac records, for example in the German Historical Museum in Berlin. These also contain communist battle songs .

- Address by Ernst Putz - Brothers, on the sun, on freedom . Berlin 1928. Speaker: Ernst Putz, Distribution: Communist Party of Germany.

- Working peasants with workers in one front - The Soviets own this earth - tractor song . Speaker: Ernst Putz, choir: Das Rote Sprachrohr , Berlin. Proletarian Record Center, Berlin 1932. Distribution: Mail order company Arbeiter-Kult.

literature

- Alois Hönig: Ernst Putz, a communist peasant leader . Phil. Diss. V. October 25, 1969, Philosophical Faculty of the University of Rostock 1969

- I. Hildebrandt, Alois Hönig: Putz, Ernst . In: History of the German labor movement. Biographical Lexicon . Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1970, pp. 370–371.

- Plaster, Ernst . In: German resistance fighters 1933–1945. Biographies and letters . Volume 2. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1970, pp. 65-67.

- Hedwig Glasneck: Ernst Putz. 1896-1933 . In: Communists in the Reichstag . Verlag Marxistische Blätter, Frankfurt am Main 1980, pp. 459–464.

- Leonhard Rugel: The Sinnthalhof and the Moritz and Putz families . In: Annual report of the Franz-Miltenberger-Gymnasium Bad Brückenau. Bad Brückenau 1982, pp. 101-106.

- Hedwig Glasneck: Ernst Putz's parliamentary struggle for an alliance with the working peasants . In: Contributions to the history of the German labor movement , Volume 29, Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1987, pp. 38–48. Edited by Institute for Marxism-Leninism at the Central Committee of the SED.

- Leonhard Rugel: The higher school of Ernst Putz in the Sinntalhof . In: Annual report of the Franz-Miltenberger-Gymnasium Bad Brückenau, 1987/88 (1988), pp. 124-134.

- Martin Schumacher (Hrsg.): MdR The Reichstag members of the Weimar Republic in the time of National Socialism. Political persecution, emigration and expatriation 1933–1945. Droste-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1991, ISBN 3-7700-5162-9 , p. 443.

- Ulrich Debler: The Jewish community of Bad Brückenau . In: Würzburger Diözesan-Geschichtsblätter , Volume 66. Ed. Würzburger Diözesan-Geschichtsverein, Würzburg 2004, pp. 125–212.

- Plaster, Ernst . In: Hermann Weber , Andreas Herbst : German Communists. Biographisches Handbuch 1918 to 1945. 2nd, revised and greatly expanded edition. Dietz, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-320-02130-6 .

- Peter Dudek : "That I went my way out of deepest conviction." - The memories of the Free School Community Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120.

- Peter Dudek: Life lived in advance - The memories of Reichstag member Ernst Putz of his school days in Wickersdorf . In: Gudrun Fiedler , Susanne Rappe-Weber , Detlef Siegfried : '' Collect - develop - network: youth culture and social movements in the archive ''. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014. ISBN 978-3-8470-0340-3 , p. 161 ff.

Web links

- Ernst Putz in the database of members of the Reichstag

- Speech by Ernst Putz during the 70th session of the Reichstag on Friday, May 3, 1929. (full text) Reichstag minutes 1928 / 30.2. Pages 1848-1853.

Individual evidence

- ^ Ernst Putz's death certificate, issued by the Berlin-Tiergarten registry office . On: mainpost.de - Various dates of his death are mentioned in the sources, July 1933, September 12 or 15, 1933. According to the death certificate of the Berlin-Tiergarten registry office, the official date is September 12, 1933, confirmed by contemporary diary entries by his sister Charlotte Plaster.

- ↑ Bundesarchiv, DY 55 / V 278/6/1438 (contains curriculum vitae and article)

- ^ Putz, Ernst in the German biography

- ^ A b c d e f g Ralf Ruppert: Searching for traces of Ernst Putz in Bad Brückenau , September 13, 2013. On: infranken.de

- ^ Officer personnel files Sebastian Putz (born January 11, 1867). In: Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, signature: BayHStA, officer personal files 27490. Holdings: 4.2.4 officer personal files.

- ↑ a b c d e Ralf Ruppert: Ernst Putz tombstone in Bad Brückenau is being polished up , October 10, 2013. On: mainpost.de

- ↑ a b c d e Peter Dudek : “That I went my way out of innermost conviction.” - The memories of the Free School Community Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, quotation point: p. 93.

- ^ Letter from Ernst Putz, Sinntalhof hostel, Brückenau, to Friedrich Pustet, Verlag Friedrich Pustet, July 30, 1926 . In: Episcopal Central Library Regensburg, Proskesche Music Department. On: kalliope-verbund.info

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Christoph Kopke , Werner Treß: The day of Potsdam - March 21, 1933 and the establishment of the National Socialist dictatorship . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2013. ISBN 978-3110305494 , p. 188.

- ↑ Peter Dudek: Vorweggelebtes Leben - The memories of the Reichstag member Ernst Putz of his Wickersdorfer school days . In: Gudrun Fiedler , Susanne Rappe-Weber , Detlef Siegfried : Collecting - opening up - networking: youth culture and social movements in the archive . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014. ISBN 978-3-8470-0340-3 , pp. 161–182, citation: pp. 176–177.

- ↑ Leonhard Rugel: The Sinnthalhof and the families Moritz and plaster . In: Annual report of the Franz-Miltenberger-Gymnasium Bad Brückenau . Bad Brückenau 1982, pp. 101-106.

- ↑ a b Ulrike Müller: New knowledge about Ernst Putz . In: Mainpost, September 3, 2015. On: mainpost.de

- ↑ a b c d e Peter Dudek: “That I went my way out of innermost conviction.” - The memories of the Free School Community Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, quotation point: p. 97.

- ↑ a b c d Peter Dudek: Life lived in advance - The memories of the Reichstag member Ernst Putz of his school days in Wickersdorf . In: Gudrun Fiedler , Susanne Rappe-Weber, Detlef Siegfried: Collecting - opening up - networking: youth culture and social movements in the archive . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014. ISBN 978-3-8470-0340-3 , pp. 161-182. Quotation: pp. 165–166.

- ^ Letter from Charlotte Putz (1903–1960) to Romano Guardini (1885–1968) dated October 2, 1958. In: Charlotte Putz estate. Private property Barbara Meyer-Jürgens, Bad Brückenau. Quoted from Peter Dudek: “That I went my way out of deepest conviction.” - The memories of the Free School Community of Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, quotation point: pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Photo: Announcement from 1907 : Extension of the Royal District Realschule to the Royal District High School in Würzburg. On: roentgen-gym.de

- ↑ Peter Dudek: Vorweggelebtes Leben - The memories of the Reichstag member Ernst Putz of his Wickersdorfer school days . In: Gudrun Fiedler, Susanne Rappe-Weber, Detlef Siegfried: Collecting - opening up - networking: youth culture and social movements in the archive . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014. ISBN 978-3-8470-0340-3 , pp. 161–182, citation: p. 177.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Notes (prison diary, memories and suicide note) from Ernst Putz in custody in Berlin-Moabit, summer 1933. Typewritten transcription of his sister Charlotte Plaster (1903–1960) without page numbers. In: Federal Archives, BArch NY 4156, StA 3.

- ↑ a b Peter Dudek: "That I went my way out of innermost conviction." - The memories of the Free School Community Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, quotation point: p. 113.

- ↑ Konrad Ackermann : Hochland - monthly for all areas of knowledge, literature and art . In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria. On: historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de

- ↑ Peter Dudek: “You are and will remain the old abstract ideologue!” The reform pedagogue Gustav Wyneken (1875-1864) - A biography . Verlag Julius Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn 2017. ISBN 978-3781521766 , p. 139.

- ^ Logbook of the Schule am Meer Juist, entry from June 21, 1933.

- ↑ a b c Peter Dudek: “Life lived in advance” - The memories of the Reichstag member Ernst Putz of his school days in Wickersdorf . In: Gudrun Fiedler , Susanne Rappe-Weber, Detlef Siegfried: Collect - open up - network. Youth culture and social movements in the archive . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014. ISBN 978-3-8470-0340-3 , pp. 161–182, citation: p. 164.

- ↑ Martin Kießig : Martin Luserke. Shape and work. Attempt to interpret the essence . Phil. Diss. University of Leipzig, J. Särchen Verlag. Berlin 1936; quoted from: The journey through life of Martin Luserke . Lecture by Kurt Sydow on the 100th birthday of Martin Luserke on May 3, 1980. On: luserke.net

- ↑ Here, in the typewritten transcription of his notes by the sister Elisabeth Putz-Valtari, a noun is missing, which is therefore also missing in the secondary academic literature (Dudek 2011, 2014).

- ↑ Peter Dudek: Fetish youth. Walter Benjamin and Siegfried Bernfeld - youth protest on the eve of the First World War . Verlag Julius Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn 2002. ISBN 978-3-7815-1226-9 , pp. 76-120.

- ↑ Youth as an Object of Science. History of youth research in Germany and Austria 1890–1933 Springer-Verlag, Berlin 2013. ISBN 978-3-322-97007-7 , p. 333.

- ^ Letter from Ernst Putz from Wickersdorf to Siegfried Bernfeld on February 18, 1914. In: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research (ייִדישער װיסנשאַפֿטלעכער אינסטיטוט), New York City. (Copy in the private archive of the Bernfeld journalist Ulrich Herrmann in Tübingen)

- ^ Reply from Gustav Wyneken to Ernst Putz dated February 11, 1914. In: Wyneken estate, No. 1035, Archive of the German Youth Movement Witzenhausen. Quoted from Peter Dudek: “That I went my way out of deepest conviction.” - The memories of the Free School Community of Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933). In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, citation: p. 94.

- ^ Gustav Wyneken: Wickersdorf . Adolf Saal Verlag, Lauenburg 1922, p. 56. Quoted from Peter Dudek : “You are and will remain the old abstract ideologue!” The reform pedagogue Gustav Wyneken (1875-1864) - A biography . Verlag Julius Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn 2017. ISBN 978-3-7815-2176-6 , pp. 112-113.

- ↑ Peter Dudek: “Life lived in advance” - The memories of the Reichstag member Ernst Putz of his school days in Wickersdorf . In: Gudrun Fiedler, Susanne Rappe-Weber, Detlef Siegfried: Collecting - opening up - networking: youth culture and social movements in the archive . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-8470-0340-3 , pp. 161–182, citation: p. 174.

- ↑ Minutes: agendas and resolutions of the school communities, 1906–1921 . In: District Archives Saalfeld-Rudolstadt.

- ↑ Peter Dudek: “That I went my way out of innermost conviction.” - The memories of the Free School Community Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, quotation point: p. 95.

- ^ Letter from Ernst Putz to Friedrich Pustet, Verlag Friedrich Pustet , July 30, 1926. In: Bischöfliche Zentralbibliothek Regensburg, Proskesche Musikabteilung. On: kalliope-verbund.info

- ^ Letter from Friedrich Pustet, Verlag Friedrich Pustet, to Ernst Putz , August 9, 1926. In: Bischöfliche Zentralbibliothek Regensburg, Proskesche Musikabteilung. On: kalliope-verbund.info

- ^ Letter from Ernst Putz to Friedrich Pustet, Verlag Friedrich Pustet , August 13, 1926. In: Bischöfliche Zentralbibliothek Regensburg, Proskesche Musikabteilung. On: kalliope-verbund.info

- ^ Letter from Friedrich Pustet, Verlag Friedrich Pustet, to Ernst Putz , August 20, 1926. In: Bischöfliche Zentralbibliothek Regensburg, Proskesche Musikabteilung. On: kalliope-verbund.info

- ↑ Otto Gründler: Elements for a philosophy of religion on a phenomenological basis . Phil. Diss. Munich. Verlag Josef Kasel & Friedrich Pustet, Munich u. Kempten in the Allgäu 1922.

- ↑ Peter Dudek: “Life lived in advance” - The memories of the Reichstag member Ernst Putz of his school days in Wickersdorf . In: Gudrun Fiedler, Susanne Rappe-Weber, Detlef Siegfried: Collecting - opening up - networking: youth culture and social movements in the archive . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-8470-0340-3 , pp. 161-182, citation: p. 180.

- ^ A b Peter Dudek: “Life lived in advance” - The memories of the Reichstag member Ernst Putz of his school days in Wickersdorf . In: Gudrun Fiedler, Susanne Rappe-Weber, Detlef Siegfried: Collecting - opening up - networking: youth culture and social movements in the archive . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-8470-0340-3 , pp. 161–182, citation: p. 179.

- ^ Officer personnel files Joseph Putz (born January 24, 1897). In: Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, signature: BayHStA, officer personal files 46476. Holdings: 4.2.4 officer personal files.

- ↑ Memorial plaque to Josef Putz and Philipp Füglein in St. Marien in the Staatsbad Brückenau , Lower Franconia.

- ↑ a b Kontreadmiral a. D. Albert Stoelzel ( arr .): Honorary ranking of the Imperial Navy 1914–18 . Edited by Navy Officer Association. Thormann & Goetsch, Berlin 1930, p. 1014.

- ↑ General Command of the Marine Corps of the Imperial Navy (Marinekorps Flanders) . In: Bundesarchiv, signature BArch, RM 120. On: deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de

- ^ Krebs, Siegfried (1882-1915) . In: Federal Archives, Central Database of Legacies. On: nachlassdatenbank.de

- ↑ Peter Dudek: “That I went my way out of innermost conviction.” - The memories of the Free School Community Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, quotation point: p. 114.

- ↑ Peter Dudek: “That I went my way out of innermost conviction.” - The memories of the Free School Community Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, quotation point: p. 112.

- ^ Lieutenant Max Krug, FEA 3, * February 2, 1897 in Münnerstadt, † April 6, 1918 in Gotha . On: frontflieger.de

- ^ Grave site Wilhelm Jerosch, Stele 27, German War Graves Cemetery, Langemark-Poelkapelle, West Flanders . On: findagrave.com

- ↑ Peter Dudek: “That I went my way out of innermost conviction.” - The memories of the Free School Community Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, citation: p. 115.

- ↑ There are two places with this name in West Flanders: en: Zandvoorde, Zonnebeke and nl: Zandvoorde (Oostende) , but the former must be meant because at the time in question it was within the front line of the German 4th Army (east of Ypres ) and had a direct road to nearby Geluwe.

- ↑ Putz, Ernst . In: Reichstag Handbuch 1924 II (1925), p. 328.

- ↑ Archive of the University of Jena, BA stock, No. 902 and No. 983.

- ^ Leonhard Rugel: The higher school of Ernst Putz in the Sinntalhof . In: Annual report of the Franz-Miltenberger-Gymnasium Bad Brückenau, 1987/88 (1988), pp. 124-134.

- ↑ a b Peter Dudek: "That I went my way out of innermost conviction." - The memories of the Free School Community Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, quotation point: pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Putz, Ernst . On: reichstag-abteilungendatenbank.de

- ↑ Brückenau, Bad. Establishment of a secondary school (Sinntalhof). In: Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, signature: BayHStA, MK 21862. Holdings: 2.8.1.4 MK 4 / 1-2.

- ↑ Torsten Fischer , Jörg W. Ziegenspeck : Experiential education: Basics of learning through experience. Experiential learning in the continuity of the historical educational movement . Verlag Julius Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn 2008. ISBN 978-3-7815-1582-6 , p. 21.

- ↑ a b c Ulrich Debler: The Jewish community of Bad Brückenau . In: Würzburger Diözesan-Geschichtsblätter , Volume 66. Würzburg 2004, pp. 125–212.

- ↑ Peter Dudek: “That I went my way out of innermost conviction.” - The memories of the Free School Community Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, citations: pp. 92, 99.

- ↑ Ehrenhard Skiera: Reform Education in Past and Present - A Critical Introduction . Oldenbourg-Verlag, Munich 2010. ISBN 978-3486591071 , p. 178.

- ^ A b c Peter Dudek: Life lived in advance - The memories of the Reichstag member Ernst Putz of his school days in Wickersdorf . In: Gudrun Fiedler , Susanne Rappe-Weber, Detlef Siegfried: Collecting - opening up - networking: youth culture and social movements in the archive . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014. ISBN 978-3-8470-0340-3 , pp. 161–182, citation: p. 168.

- ↑ Irmgard Heidler: The publisher Eugen Diederichs and his world (1896-1930) . (= Mainzer Studien zur Buchwissenschaft 8) Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 1998. ISBN 978-3447040297 , pp. 52, 57, 884.

- ↑ Irmgard Heidler: The publisher Eugen Diederichs and his world (1896-1930) . (= Mainzer Studien zur Buchwissenschaft 8) Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 1998. ISBN 978-3447040297 , p. 887.

- ↑ Max Bondy: The new worldview of education - Dedicated to the German Academic Freischar . Eugen Diederichs, Jena 1922.

- ^ Leonhard Rugel: On the history of the Franz-Miltenberger-Gymnasium . In: Annual report of the Franz-Miltenberger-Gymnasium 1973/74. Bad Brückenau 1974, pp. 2-25, pp. 49-65.

- ↑ Peter Dudek: “That I went my way out of innermost conviction.” - The memories of the Free School Community Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, quotation point: p. 102.

- ↑ Birgit S. Nielsen: Horst Horster (1903–1981), silversmith . In: Willy Dähnhardt, Birgit S. Nielsen (Ed.): German-speaking scientists, artists and writers in Danish exile after 1933 . Boyens, Heide 1993, ISBN 978-3804205697 , pp. 331-336.

- ^ A b Josef Reinhold: The KPD and the Federation of Schaffender Landwirte in the Rhön 1924–1933 . In: Yearbook for Regional History (JbRegG) Vol. 15, Part I (1988). Edited on behalf of the Historical Commission of the Saxon Academy of Sciences. Hermann Böhlaus Nachf., Weimar 1988. ISBN 3-7400-0010-4 , p. 211.

- ^ Carsten Voigt: Combat leagues of the workers' movement: the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold and the Rote Frontkampfbund in Saxony 1924–1933 . Böhlau Verlag, Cologne, Weimar 2009. ISBN 978-3412204495 , pp. 335-336, 511.

- ↑ Manfred Kittel: Province between Empire and Republic: Political Mentalities in Germany and France 1918–1933 / 36 . Oldenbourg-Verlag, Munich 2000. ISBN 978-3486596106 , pp. 196-197.

- ↑ a b c d e f Arnd Bauerkämper: Rural society in the communist dictatorship. Forced modernization and tradition in Brandenburg 1945–1963 . Böhlau-Verlag, Cologne, Weimar 2002. ISBN 978-3-412-16101-9 , pp. 59-60.

- ^ District Secretariat of the Federation of Working Farmers in the Erzgebirge / Vogtland District . In: German Digital Library / German Photo Library. On: deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de

- ↑ Wolfgang Hesse: The lens to the village! Land and landscape in the proletarian amateur photography of the Weimar Republic In: Bertram Kaschek, Jürgen Müller, Wilfried Wiegand (eds.): Taking pictures - photography as practice . Exhibition catalog, Dresden 2010. pp. 55–68.

- ^ Beginning of the peasant movement in the Rhön in the mid-1920s . On: rhoen.info

- ↑ Photo: leaflet To the German smallholders! (Farmer Putz's yard surrounded by the Reichswehr, searched by detectives). In: German Historical Museum, inventory no. Thu 59 / 711.1. On: dhm.de

- ↑ Putz, Ernst . In: Reichstag Handbook, 3rd electoral period . Berlin 1925. p. 408.

- ↑ a b c Putz, Ernst . In: Hermann Weber, Andreas Herbst: German Communists. Biographisches Handbuch 1918 to 1945. 2nd, revised and greatly expanded edition. Dietz, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-320-02130-6 .

- ↑ Photo: Appeal of the Reichs-Bauernbund and the Federation of Working Farmers for the Prussian state and Reichstag elections in 1928 . In: German Historical Museum , Berlin. Inventory number Do 57 / 1332.26

- ↑ Herbert Crüger: Secret times: from the secret apparatus of the KPD to the state security prison . Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 1990. ISBN 978-3861530022 , pp. 51-52.

- ↑ Alois Hönig: Ernst Putz, a communist peasant leader . Phil. Diss. V. October 25, 1969, Philosophical Faculty of the University of Rostock 1969. Quoted from Peter Dudek: “That I went my way out of innermost conviction.” - The memories of the Free School Community of Wickersdorf in the prison diary of KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, quotation point: p. 103.

- ^ Ernst Thälmann proclaims: Communist Party's peasant aid program . Author: Ernst Thälmann, Bruno von Salomon, publisher: Ernst Putz, Communist Party of Germany (KPD), printer: City-Druckerei AG. On: deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de

- ↑ Renata von Hanffstengel: Mexico in the work of Bodo Uhse: the never-abandoned exile . Peter Lang International Publishers of Science, 1995. p. Xii.

- ↑ Ernst Putz. Files of the Reich Security Main Office: decomposition . In: Federal Archives, Berlin-Lichterfelde site, Section R 2, inventory signature BArch R 58/2221 Vol. 13, running from January 1925 to March 1935.

- ↑ History of the German labor movement. Biographical Lexicon . Berlin (East) 1970. p. 370 f. Quoted from: Arnd Bauerkämper: Rural Society in the Communist Dictatorship: Forced Modernization and Tradition in Brandenburg 1945-1963 . Böhlau Verlag, Cologne u. Weimar 2002. ISBN 978-3-412-16101-9 , p. 59.

- ^ Demands of the KPD based on illegality, March 1933, hectographed leaflet. On: deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de

- ↑ Peter Dudek: “That I went my way out of innermost conviction.” - The memories of the Free School Community Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, quotation point: pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Charlotte Putz: “My brother, who was bound by deep friendship [...] committed suicide in 1933 in the prison in Moabit. It was shortly before the verdict that our old father and us sisters would have taken home and wealth ”. Quoted from: Ulrike Müller: New findings about Ernst Putz . In: Mainpost, September 3, 2015. On: mainpost.de

- ↑ a b Peter Dudek: "That I went my way out of innermost conviction." - The memories of the Free School Community Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, quotation point: p. 106.

- ^ Letter from Charlotte Putz (1903–1960) to Romano Guardini (1885–1968) dated October 2, 1958. In: Charlotte Putz estate. Private property Barbara Meyer-Jürgens, Bad Brückenau. Quoted from Peter Dudek: “That I went my way out of deepest conviction.” - The memories of the Free School Community of Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933). In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, quotation point: p. 106.

- ↑ Quote: “12. September 1933. […] Putz, communist member of the Reichstag, found dead in Berlin-Moabit prison. The prison authorities claim suicide. (Official report). “In: Brown Book II: Dimitroff contra Goering - Revelations about the real arsonists . Editions du carrefour, Paris 1934. Reprint Cologne / Frankfurt am Main 1981, ISBN 3-7609-0552-8 , p. 446. Quoted from: Christoph Kopke, Werner Treß: The day of Potsdam - March 21, 1933 and the establishment of the National Socialist dictatorship . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2013. ISBN 978-3110305494 , p. 188.

- ↑ Peter Dudek: “That I went my way out of innermost conviction.” - The memories of the Free School Community Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, citation: p. 104.

- ↑ Alois Hönig: The farmer from the Sinntalhof - Ernst Putz . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement , Volume 9. Ed. Institute for Marxism-Leninism at the Central Committee of the SED. Dietz, Berlin 1967, pp. 713-718. (Federal Archives DY 30/36630)

- ↑ a b Peter Dudek: "That I went my way out of innermost conviction." - The memories of the Free School Community Wickersdorf in the prison diary of the KPD Reichstag member Ernst Putz (1896–1933) . In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement (BzG), 3 (2011), pp. 91–120, quotation point: p. 98.

- ↑ Member of the Bavarian State Parliament (first electoral period) 1919–1920 . In: House of Bavarian History. Bavarian State Ministry for Education and Culture, Science and Art. On: hdbg.de (click on MPs, see there: BVP)

- ↑ Member of the Bavarian State Parliament (second electoral period) 1920–1924 . In: House of Bavarian History. Bavarian State Ministry for Education and Culture, Science and Art. On: hdbg.de (click on MPs, see there: BVP)

- ↑ Member of the Bavarian State Parliament (third electoral term) 1924–1928 . In: House of Bavarian History. Bavarian State Ministry for Education and Culture, Science and Art. On: hdbg.de (click on MPs, see there: BVP)

- ↑ Member of the Bavarian State Parliament (fourth electoral period) 1928–1932 . In: House of Bavarian History. Bavarian State Ministry for Education and Culture, Science and Art. On: hdbg.de (click on MPs, see there: BVP)

- ↑ Member of the Bavarian State Parliament (fifth electoral period) 1932–1933 . In: House of Bavarian History. Bavarian State Ministry for Education and Culture, Science and Art. On: hdbg.de (click on MPs, see there: BVP)

- ↑ Peter Dudek: Vorweggelebtes Leben - The memories of the Reichstag member Ernst Putz of his Wickersdorfer school days . In: Gudrun Fiedler , Susanne Rappe-Weber, Detlef Siegfried: Collecting - opening up - networking: youth culture and social movements in the archive . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014. ISBN 978-3-8470-0340-3 , pp. 161–182, citation: p. 176.

- ↑ Memory of Ernst Putz . In: Neues Deutschland, March 14, 1964. On: nd-archiv.de

- ↑ Revolutionary leader of the working peasants - Ernst Putz was murdered 50 years ago today . In: Neues Deutschland, September 15, 1983. On: nd-archiv.de

- ^ Organized anti-fascist front in the countryside . In: Neues Deutschland, September 15, 1983. On: nd-archiv.de

- ↑ Rudolf Rößler: interests of the peasants defended - 90 years ago the communist Ernst Putz was born . In: Neues Deutschland, January 18, 1986. On: nd-archiv.de

- ↑ Photo: Ernst-Putz-Schule, Neurüdnitz an der Oder. In: Bundesarchiv, signature picture 183-13123-0001.

- ↑ Photo: MTS Ernst Putz, Jahna, Meißen district, Dresden district. In: Bundesarchiv, signature picture 183-18178-0038.

- ^ Photo: MTS Ernst Putz (President Wilhelm Pieck awards Ernst Kriesche, combine harvester driver, MTS Ernst Putz Zuchau, Magdeburg district, the honorary title of hero of work . For reasons for the award, see ADN message no. 200 of October 13, 1955). Zuchau, District Magdeburg. In: Bundesarchiv, signature picture 183-33415-0007.

- ^ Ingrid Ehlers, Ernst Fiedler, Klaus Haese et al .: Memorials of the workers' movement in the Rostock district . SED Rostock 1981.

- ↑ NVA barracks Ernst Putz . In: Neues Deutschland, March 1, 1965. On: nd-archiv.de

- ^ Workers and soldiers celebrated the anniversary of the NVA together . In: Neues Deutschland, March 2, 1988. On: nd-archiv.de

- ^ Photo: Inauguration of the plaster memorial stone 1984 in Oberweid . On: Mainpost.de

- ↑ Memorial stone for Ernst Putz in Oberweid . On: mainpost.de

- ↑ Address by Ernst Putz - Brothers, on the sun, on freedom . In: German Historical Museum, Berlin, inventory no. T 66 / 19.3. On: dhm.de

- ↑ Working peasants with workers in a front - The Soviets own this earth - tractor song . In: German Historical Museum, Berlin, inventory no. T 72/51. On: dhm.de

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Plaster, Ernst |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Putz, Ernst Raimund Hermann (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German politician (independent, KPD), MdR |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 20, 1896 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Sinntalhof , Bad Brückenau |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 12, 1933 |

| Place of death | Berlin-Moabit |