Hamburg port workers strike 1896/97

The Hamburg port workers' strike of 1896/97 is one of the largest labor disputes in the German Empire . It began on November 21, 1896, lasted eleven weeks, included nearly 17,000 workers at its peak, and ended on February 6, 1897 with the complete defeat of the strikers. The dispute had a significant impact on Hamburg's economy and also caused a stir outside of Germany. The strike was mainly carried out by groups of workers who were barely unionized and whose working conditions were characterized by discontinuity. They faced well-organized entrepreneurs. The events gave the conservatives and the imperial government an opportunity two years later to attempt an intensified policy of repression against social democracy with the prison bill .

Requirements and history

Importance of the port of Hamburg

Hamburg had been Germany's leading trading and shipping center since the middle of the 19th century. The city's port was its economic center. In the years from 1856 to 1886, the number of goods imported by ship in Hamburg tripled, which was mainly due to the intensified trade relations with Latin America after this region broke away from Portugal and Spain . In addition, there was emigration to America . It reduced the freight rates for goods traffic from America to Hamburg, because the freight space for journeys from Europe to America was used and paid for.

The economic center of the port also shaped Hamburg's industry, which was strongly oriented towards export. The production of goods with high quality craftsmanship played a greater role here than in industrial regions in which mass production predominated. In addition, there was the production of large goods: the ships at the Hamburg shipyards .

The competitiveness of the port of Hamburg grew during the German Empire. The Port of Hamburg's share of shipping traffic in Germany, measured in net register tons , was just under 30 percent in 1873. This made Hamburg the undisputed number one of the German port cities. Bremen / Bremerhaven followed by a long way with a share of almost 12 percent. Hamburg's share grew to over 40 percent by 1893, to reach more than 44 percent in 1911. The ports on the Weser , still in second place, were only able to improve their share by half a percentage point by 1911. The great advantage of the Port of Hamburg was its good connection to the hinterland . There was an extensive system of inland waterways and railways to and from Hamburg. From Hamburg's point of view, this hinterland extended beyond the German borders. As a transit station, the port was also of great importance for the movement of goods between parts of Central and Eastern Europe and the “New World”. In particular, the flow of goods from and to Austria-Hungary , the Balkan states , Scandinavia and, in some cases, Russia also ran through Hamburg.

The Hanseatic city drew a large part of its economic and political power from the port. There was thus also a potential for losses, especially if the port industry - for example due to strikes - came to a standstill.

Union organization

Hamburg was the center of the socialist trade union movement in Germany. In 1890 the city had 84 trade unions, almost every workers' group here had its own organization, which together represented more than 30,000 members. Another expression of Hamburg's prominent position for the German trade union movement was the fact that the General Commission of Germany's trade unions had its seat in the port city, as did a number of central boards of the individual associations. The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) had also turned the Elbe city into a stronghold. In 1890 the party captured all three Hamburg seats in the Reichstag and defended them until the end of the empire. However, in 1896 the Hamburg labor movement was not far back from a severe defeat. Six years earlier, there had been in a number of countries the attempt on May 1 , the introduction of the eight-hour day and a noticeable reduction in working hours to erstreiken. In Germany these disputes soon concentrated on the Elbe metropolis. In the May fights in Hamburg, however, the strikers were faced with a “highly armed and well-organized block of entrepreneurs whose power and determination could hardly be underestimated”. This power block refused concessions and responded with mass lockouts and further sanctions. The defeat of the strikers after weeks of fighting led to a considerable decline in membership of the Hamburg trade unions.

The deteriorating economy was also responsible for this development in membership numbers . The central port workers 'association, newly founded in 1891, included all workers' groups in the Port of Hamburg and had around 5,000 members that year, but in the following year only 1,800 unionists were united. The Hamburg cholera epidemic of 1892 was partly responsible for this decline. Furthermore, in 1892 the group of the Schauer People took a special organizational path, they separated from the Central Association and founded the Association of Schauer People employed in Hamburg from 1892, an independent, localist organization. Criticism of the functionaries , of centralized structures, of the use of membership fees and of the burden on individual members through regular membership fees were the reasons given for the split.

Differences and similarities among dock workers

The port workers were heterogeneous. At least 15 different professional groups emerged from the different activities. After the largest group of showers, the Ewer leaders were numerically significant. They took care of the transport of the goods to and from the seagoing vessels by water. So-called barges were used for this purpose . Although the importance of the Ewerführung decreased since the 1860s, because the ships were increasingly no longer loaded and unloaded "in the river" but at the newly built quays , this trade was the most important branch of Hamburg's port shipping. Even moored at the quay ships were on the water side of Ewerführern deleted and loaded, so that for shipowners unproductive time spent stopped short as possible. The wharf workers were also a large professional group. Your responsibility lay in loading cargo from the ships into the warehouses on the quays or on carts or in railroad cars for immediate onward transport. Storage workers moved the goods around the warehouses and loaded the barges that brought the goods to the ships. In addition to these occupational groups, there were others such as coal workers, grain workers, boiler cleaners, ship cleaners, ship painters and machinists. In a broader sense, there were around 13,000 seafarers who were divided into different ranks and professions and who lived in Hamburg.

Despite this internal differentiation, there were a number of similarities. The workers were often exposed to high levels of physical strain, often in hazardous and accident-prone environments. The work was done at every time of the day, night and season. Many of the workers also came from the Gängeviertel , a cramped residential area near the port. The vast majority were unskilled and had no permanent employment relationships. Exceptions to this were the Ewerführer and the machinists, whose activity required several years of apprenticeship. Other characteristics of the work were the extremely short employment relationships and the abrupt change between unemployment and days of work without interruption, which could last up to 72 hours at peak times. Only the skilled workers and the state quay workers were independent of these vicissitudes. The lack of a regulated, officially controlled employment agency made matters worse. The recruitment of workers often took place in harbor bars, which were "the real centers of job placement" until the 20th century. The chance of employment was therefore dependent on consumption and on the personal relationship with hosts and agents. Shipowners and merchants no longer selected the workers required in the port themselves, but instead commissioned intermediate contractors, the so-called Baase, and their foremen, known as Vizen. In addition, some business associations in Hamburg had started to set up work records on their own. In this way they hoped to be able to consistently exclude unpopular workers from employment. The "Hamburg system" of entrepreneur-dominated evidence spread from the Hanseatic city across Germany. These forms of job placement took place in a labor market that was always characterized by a clear surplus of labor. Another unifying feature of the workforce was their low level of unionization, which resulted primarily from the lack of relevant vocational training and the high fluctuation . The discontinuity of employment also resulted in the port workers' comparatively high propensity to strike. As day laborers , if a strike was limited to a few days, they did not have to fear losing their jobs and receiving regular income - in contrast to workers in permanent employment. The relatively high tendency to strike was due to the limited influence of the trade unions, who viewed the strike as a last resort and put a long and complicated internal union decision-making process ahead of it.

Lower standard of living

Most of the wage agreements for the Port of Hamburg date from the 1880s. There were hardly any increases afterwards, but decreases more frequently. The pace of work had increased since then, as had the cost of living. The customs union of Hamburg had led in 1888 to a series of sometimes massive price increases. The free port created in the same year led to the demolition of apartments near the port , and the land was now to be used as industrial and commercial space. The homes of around 24,000 people disappeared. The rents for the remaining apartments near the port rose dramatically. A large number of those employed in the port had to look for living space in distant parts of the city such as Eimsbüttel , Winterhude , Barmbek , Hamm or Billwerder . In all cases, higher rents were also to be paid there, and travel times to the port were significantly longer.

course

prolog

The chance of an improvement in the income situation only arose when the economy picked up significantly in the spring of 1896. Unemployment fell noticeably, the number of union members rose, freight rates doubled, and contemporary observers spoke of a veritable grain boom in August, which led to many ships crowding into the port. The balance sheets of the owners reported significant profits from. In September and October, the Akkord- Schauer People reacted to the improved economic conditions with two short strikes, each of which ended victoriously for them. The strikes were organized by the localist union Verein der Schauer People from 1892 , chaired by Johann Döring. Other groups of dockworkers were also successful with wage strikes during these two months, such as the coal workers, the grain workers, the quay workers and a subgroup of the ship cleaners.

The tense situation was exacerbated by the arrest and deportation of the English port worker leader Tom Mann , who was also known in Germany and who wanted to promote the union organization of port workers in Hamburg and Altona in mid-September 1896. This official measure was perceived by wide circles of the unorganized dockworkers as an inadmissible and defamatory restriction of the freedom of association . As a result, the expulsion produced the opposite of its intention: events dealing with Mann's treatment were very well attended, and wages and working conditions were soon discussed at them. Occasionally speakers even called for the defeat of 1890 to be stamped out.

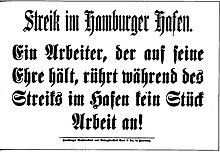

Beginning and extension of the strike

The centralized port workers' association was reserved when it came to strike actions; the leaders of this association considered the level of union density to be too low to be able to successfully carry out strikes. They also feared an army of strikebreakers because the seasonal layoffs of agricultural and construction workers were imminent. On November 12, 1896, a meeting of association members refused to show solidarity with general cargo showmen willing to strike. Four days later, however, the mood turned. At another meeting, the majority of those present spoke out against the advice of all union officials in favor of supporting the general cargo showers. After another four days, on November 20th, the big strike, which has gone down in history as the Hamburg dockworkers ' strike, was resolved : with an overwhelming majority, the members of the dockworkers' association also decided to walk out on November 21st. The entrepreneurs had previously indicated their consent to a general increase in wages. At the same time, however, they wanted to reduce the surcharges that were paid when handling goods that were harmful to health. At the time, nobody expected that the strike would develop into a labor dispute lasting several weeks. The general assumption was that the strike lasted eight to 14 days.

On November 21, 1896, almost all the showers stopped working. The other groups of workers employed in the port also started strikes in the next few days and raised demands that were strictly rejected by the employers. These turned out differently for the individual groups of workers. They can essentially be broken down into those that relate to the basic wage, wage supplements and working hours. In addition, the advocacy of a collective agreement regulation of the working conditions - the trade unions were by no means regarded by the employers as negotiating partners on these issues in 1896. The shutdown of the Baasen was also requested. The negative answers of the entrepreneurs accelerated the wave of reclamations. At the end of November, more than 8,700 strikers were counted. On December 4th, there were almost 12,000. On December 9, that number was 14,500, and on December 21, it was more than 16,400.

Organization of the strike

The individual professional groups elected strike commissions, which met in a central strike committee of around 70 people. This committee was headed by a five-person board, the chairman of this steering committee was the localist Döring. Representatives of the Hamburg trade union cartel , i.e. the local trade union umbrella organization, were initially not involved, as were representatives of the SPD. However, they stepped in when the first attempts at arbitration were made. These prominent workers leaders included Carl Legien , Hermann Molkenbuhr , Karl Frohme, and Adolph von Elm . Each striker was given a strike card that had to be stamped daily. Pickets were distributed in the port to ensure that the strike was carried out consistently. At the same time barges were chartered in order to be able to carry out patrol trips .

The organization of support funds became decisive for the intensity of the strike. The financial resources of the port workers' union were insufficient to sustain a strike for long, and the resources of the localist organization of the showers were even less suitable. Although the union cartel was not involved in calling the strike and worked to contain and dampen the conflict over the following weeks, it recognized the strike on November 27. It asked the other unions for financial support. These measures were not limited to the Hanseatic city; rather, donations were acquired across the empire. The support of the strikers reached a level never before reached in Germany. Donations were even received from abroad, albeit to a limited extent - many dockworkers' unions abroad were not very happy about the outbreak of the strike in Hamburg. They feared that the development of the international dockworkers movement could be damaged. These appeals were not only successful in the social milieu of the workers. Many small shopkeepers also supported the strike because dock workers provided the majority of their customers. In the same way, the "hawkers" took sides, who lived from the sale of their goods on barges and in the port area. They had already declared their solidarity with the strikers on November 25th. Even the civil National Social Association expressed its solidarity with the dock workers and organized a collection of money among its supporters, which brought in a total of 10,600 marks. The calls for financial solidarity led to the fact that from December 2, 1896 every striker could be paid a strike fee of 8 marks per week, for spouses and for each child there was a surcharge of one mark each. These support rates could be increased twice during the course of the strike. For the duration of the strike, it was important that the strike pay exceeded the support rates of the public poor institution. Nevertheless, the strike pay was not generous, as a comparison with the day wages shows. At that time these were between 2 marks for boiler cleaners and 4.20 marks for showers.

Another factor in organizing the strike was the targeted addressing of women at specially organized mass events. In this way, intra-family conflicts and the resulting crumbling of the strike front should be prevented. This tactic was still relatively new in the course of labor disputes and has proven its worth in retrospect from a functionaries' point of view. Luise Zietz , who herself agitated at gatherings of dock workers' women, praised her at the SPD party convention that took place in Hamburg in October 1897.

Reactions in the entrepreneur camp

The entrepreneurs' response was not primarily determined by the employers directly affected, i.e. the Baasen and shipping companies. Instead, it was shaped by the policy of the local employers 'association ( Hamburg-Altona employers' association ), which had been founded four years earlier. Within this association, the key players speculated on a rapid collapse of the strike, because they knew very well the financial weakness of the relevant professional unions. For this reason, the strikers' demands were strictly rejected. Even when shipowners, who were financially badly affected, pressed for a relaxation of the negative policy, they could not prevail. In the eyes of the hardliners , giving in would also have meant recognizing the trade unions as negotiating partners, a step they were not ready to take.

The entrepreneurs recruited strike breakers at home and abroad to keep operations in the port up and running and to undermine the fighting strength of the strikers. On December 7, 1896, around 2000 were working in the port. The employers achieved their goals only to a limited extent: A number of the recruits allowed themselves to be prevented from starting work by the arguments of the picket lines. The labor productivity of the recruited was also significantly lower, because they were hardly familiar with the procedures of port work. Albert Ballin , director of the Hamburg-American Packetfahrt-Actien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG), thought only half of the temporary workers employed in his company were usable. The conditions on the quays and in the sheds were therefore chaotic. The number of ships waiting for loading and unloading increased steadily. The consequences for other branches of the economy were considerable, because there was now a lack of raw materials and intermediate products, which were piled up in the ships, on the quays and in sheds. Complaints about delayed delivery came in from everywhere.

Solidarity with the entrepreneurs

Kaiser Wilhelm II was the most prominent advocate of an uncompromising policy towards the strikers. He attended on November 27, 1896 Alfred von Waldersee , the neighboring Altona as Commanding General of the IX. Army Corps commanded. The emperor wished for “energetic intervention” and encouraged his general before leaving: “Just take it properly, even without asking.” A few days later he instructed the Prussian Justice Minister Karl Heinrich von Schönstedt to initiate public prosecution investigations against Social Democratic MPs who were in Port cities organized solidarity measures with the strikers in Hamburg. He instructed his Minister of War, Heinrich von Goßler , who had been in office since mid-August 1896 , to be ready to impose the state of siege .

The imperial government expressed itself in a similar way. Karl Heinrich von Boetticher , State Secretary in the Reich Office of the Interior , asserted before the Reichstag at the beginning of December 1896 that the dock workers' strike was unfounded. He based his argumentation on pay tables that were leaked to him by the employer. Carl Ferdinand von Stumm-Halberg , a major entrepreneur in the Saarland coal and steel industry and free-conservative politician, raised the mood against the striking workers in the Reichstag. He considered this strike to be the work of the SPD and the English trade unions, thinking about negotiated solutions was " nonsense ". The Association of German Iron and Steel Industrialists , an important representation of the interests of heavy industrial entrepreneurs on the Rhine and Ruhr, publicly praised the service that the Hamburg employers rendered to the fatherland, because “every even only apparent success of the workers” would threaten the internationalist endeavors of their organizations “in increase in the most threatening way ”.

Arbitration efforts

The Hamburg Senate was initially passive. Until late November 1896, he did not formally deal with the strike. However, the police occupied the port area and the quays from November 26th. Police posts were also set up in front of employment verification offices, and the authorities wanted to stop the strike. At the same time, around 1,000 Italians willing to work as strike breakers were refused entry. The request of shipowners to use naval units was also rejected. Overall, the official line in this strike phase followed an avoidance of escalations.

The initiative for an understanding did not come from the Senate, but from well-known personalities. Senator Gerhard Hachmann , responsible for the police, Siegmund Hinrichsen , President of the Hamburg Parliament and Dr. Noack, chairman of the Hamburg industrial court , started an attempt at compromise on November 29, 1896: a court of arbitration should be set up. Members of this body should be an employer representative and four representatives from the workers' side. All sides should acknowledge, in advance, decisions that have been supported by at least six arbitration panel members as binding. The workers agreed to this request. Entrepreneurs are different. They considered it the wrong signal to put workers' representatives on an equal footing with representatives of the bourgeoisie . A court of arbitration would also have meant recognizing the strikers' claims as justified in principle, even if the subtleties of pay and working conditions still had to be negotiated. Instead, the business side continued to speculate that time would work against the strikers. The employers were hoping for what the strikers feared: The strike money would slowly dry up, the strike breakers would familiarize themselves and the labor supply would also increase significantly due to the cold season. The entrepreneurs spoke publicly about understanding the conflict not as a conflict of economic interests, but as a "power struggle". In this controversy, what mattered to them was the decisive victory, not a partial success.

This statement embittered the strikers and reduced their willingness to compromise. Instead, the strike leadership called a general strike across the entire port. The solidifying fronts, the duration of the strike, the obvious problems in the port and the financial consequences of the strike prompted the Senate to intervene. On December 4, 1896, he commissioned a commission of four senators - Hachmann, William Henry O'Swald , Johann Heinrich Burchard and Alexander Kähler - to work out a proposed solution. This initiative met with interest from the strike leaders. However, it was important to them that the workers' right to form coalitions would be recognized as part of the compromise finding. However, the entrepreneurs stuck to their negative attitude. The shipbuilding entrepreneur Hermann Blohm , one of the spokesmen in the business camp, made it clear that the strike was to be understood as a dispute between the state-sustaining business community and the social democrats. This party was to be dealt a devastating blow, and help from the Senate was expected. Blohm wanted a Senate appeal that strongly disapproved of the strikers' actions. The Senate did not respond to this demand, but explored possibilities of resuming work and negotiations via a Senate appeal. The Senate had in mind a declaration that an investigation by the Senate into the complaints and demands of the strikers would begin when work was resumed. Employers should be called upon to reinstate all strikers and to dismiss foreign strikers accordingly. The strike leaders were just as disagreed with this concept as the employers. The workers' leaders emphasized that such a call could in no way guarantee the reinstatement of the strikers and the absence of corporate repression against strikers. To promote the resumption of work on such an uncertain basis is pointless. For their part, the employers again rejected the idea of direct negotiations with the unions. At the same time, they could not be determined to reinstate striking workers. For them, only the envisaged Senate investigation came into question, if it also took the interests of the entrepreneurs into account. However, they called for the Senate to publicly disapprove of the workers' struggle. The Senate rejected this request of the entrepreneurs on December 9, 1896 with a majority of ten to seven votes.

Continuation of the strike and the onset of winter

The strike continued. The authorities were now tending more and more to the employer side. They forbade the strikers from entering the free port area. Wherever strikers stood together in groups or were in the vicinity of those willing to work, they were dispersed by the police. On December 14, the Senate banned house gatherings for the strikers. The trade unions circumvented this measure, however, by distributing statements in which those willing to donate asked the collectors to come to their apartment regularly to receive the donation. However, annoyance and radicalism among the workers increased. Sometimes they resorted to acts of sabotage . Again and again loaded barges, launches and other watercraft drifted without a driver in the harbor basin and in the Elbe stream. Strikers were suspected of having sunk a steamer intended to provide emergency quarters for strikers. A pub that belonged to a Schauerbaas was devastated.

The onset of frost worked against the strikers, because the associated increasing unemployment led to a drop in donations for the dock workers. Unemployed boatmen, machinists and other inland shipping workers competed with the strikers. In addition, the number of ships in the port decreased.

In this situation, the strike leaders approached the Senate again on December 16, 1896 and asked for mediation . The entrepreneurs countered by ruling out any arbitration solution - this would be a victory for the strikers. They insisted on an immediate end to the strike, but they were not ready to talk beforehand. The Senate took the entrepreneurial line. On December 18, he also publicly called for an immediate end to the strike, only then could there be an investigation into the work situation in the port. The Senate did not make any promises to the workers. Nevertheless, the strike leadership decided to recommend that the strike be broken off. She foresaw a crumbling willingness to strike. In addition, she feared that she would have to take out loans to finance the strike, which would considerably limit her ability to strike in the future. In addition, they expected police actions to enforce the end of the strike and thus overall a defeat with years of paralysis of the workers. The strike leadership could not prevail in the strike meetings with this recommendation. Only a minority of 3,671 workers voted to end the strike. It consisted mostly of quay workers and landlords who feared the loss of permanent employment. The majority - 7,262 people - rejected the recommendation as a surrender on December 19 . She neither believed that there would be no repression, nor did she expect anything substantial from a Senate commission to investigate employment relationships.

The strike continued over the Christmas holidays into the New Year, as did an attempt to undermine the stoppage by using strikebreakers. These could get to their workplaces because it was not possible for the strikers to get all machinists to strike. For years this group of workers had largely kept their distance from the social democratic trade union movement. Many machinists who worked daily in the semi-darkness of the engine room, isolated from other groups of workers, viewed themselves more as captains and shop stewards of the employers. The remaining machinists kept the transport in the port area upright in any case. The official reprisals against the strikers intensified. The number of arrests , criminal charges and penal orders against strikers skyrocketed. Strike funds were confiscated. The authorities imposed a minor state of siege over the entire port area in mid-January , so that the strikers were no longer allowed to enter it.

Because the dock workers were not ready to give up in mid-January 1897, despite the more than seven weeks of strike, resistance against the hard line began to increase within the employers' camp. In particular, the shipowners and export merchants pushed for a change in the route. They feared that a weather change expected in the next few days would lead to a considerably increased demand for loading and unloading of newly arriving ships. That would have shifted the balance back in favor of the strikers. After the onset of the thaw, an end to the strike was hardly foreseeable, and the financial losses threatened to worsen. The Hamburg-Altona employers' association therefore suggested that the Senate - not the strikers - appoint an official port inspector on a permanent basis. In the future, he should monitor the conditions in the port and - where necessary - bring about improvements together with entrepreneurs and workers. Before this happens, however, the resumption of work is mandatory. The Senate did not comment on this initiative, but the strike leadership did. She did not like the fact that again no guarantees were given to reinstate her, to refrain from taking measures and to consider her complaints and complaints, but she did not want to let the chance of communication slip by. However, because direct negotiations between trade unions and employers remained a taboo in the eyes of the latter, the groups willing to talk met on January 16, 1897 in the Hamburg stock exchange . The starting position for a compromise was improved because the employers had indirectly agreed to negotiations with delegates from the strikers, and the call for a port inspector was an old demand of the unions. However, the representatives of the strikers insisted on binding assurances that the demands they had put forward for weeks after the end of the strike would actually be implemented. They suggested a gradual and time-consuming process for resolving the points of conflict. Despite the conflicting ideas about the terms, procedures and content of the negotiations, these direct contacts seemed to bring a different end to the conflict within reach.

End of the strike

However, an unexpected declaration of solidarity from a third party caused the fronts to harden again and ultimately to the failure of the unification initiative that had been tackled in the stock exchange on January 16, 1897. Liberal politicians and university professors appealed to the German population to support the Hamburg port workers; they saw in the demands of the employers the unacceptable intention of forcing the other side into unconditional submission. The signatories of the "Professors Call" included Friedrich Naumann , Otto Baumgarten , Heinrich Herkner , Ignaz Jastrow , Johannes Lehmann-Hohenberg , Moritz von Egidy and Ferdinand Tönnies . The appeal brought in about 40,000 marks in donations, but the entrepreneurs embittered this intervention immensely, so that the hardliners within their association now regained the upper hand. On January 21, 1897, the employers therefore rejected the dispute settlement procedure proposed by the strike representatives. Police director Roscher viewed the professors' intervention as a “clumsy tactical mistake” because it came “at the most inopportune moment”. In view of this hardening in the employers' camp, the strike leadership for its part gave up their demand for all strikers to be reinstated. However, this concession was ineffective because the entrepreneurs no longer responded to requests for talks.

The weather further weakened the strikers considerably, as the expected thaw did not materialize. The persistent frost now worked as anticipated by the strike leadership: the number of ships to be supplied remained small. The number of unemployed increased, which was detrimental to the donations - on January 26th the strike fee had to be cut by 3 marks. By stopping shipping traffic on the Upper Elbe , qualified workers could be mobilized for work in the Port of Hamburg. The long duration of the strike noticeably improved the work performance of the strike breakers; they had meanwhile become familiar with the situation.

At the end of January 1897, the strike leadership therefore advised an unconditional cessation of the industrial action. 72 percent of the electorate rejected this proposal in a ballot on January 30, 1897. Only one week later, when the strike had reached its greatest extent after eleven weeks with 16,960 strike money recipients, the majority of 66 percent of the voters decided in favor of the unconditional and immediate cessation of the strike.

On the day the strike was over, violent clashes broke out, especially in Hamburg's Neustadt district . Strikebreakers had fired revolver shots and thus provoked thousands to gather at the Schaarmarkt. They fought street battles with the approaching police . The police broke up the crowd at gunpoint, and the number of people injured in these clashes was estimated at 150. Similar riots broke out in the days that followed. A large number of the strikebreakers fled the city under the impression of this open violence. This increased the chances of reinstatement for the strikers.

Results and consequences

Triumph of the entrepreneurs and repression

While the workers had to digest a total defeat, the employers triumphed publicly. They believed that they had dealt a strong blow to the “international social democracy” and decided the “question of power” for themselves. With the intransigence demonstrated, they did not only do the Hamburg economy and shipping service a service, but also the whole of German working life. The "civil order on which the weal and woe of all our fellow citizens rests" has been defended.

The reactions of the entrepreneurs were not limited to journalistic exaggerations. The strikers learned what many of them feared. They were only reinstated in rare cases. Many entrepreneurs asked for a written statement to keep peace with the scabbards. Some Baase asked for union membership certificates and tore them up. Many workers had to accept lower wages than before the strike. As an employer, the state also knew no mercy. Initially, none of the state quay workers' strike was reinstated. Later, those re-employed had to accept lower-paid jobs as unskilled workers. The post of quay director was filled with a proven opponent of social democracy after the end of the strike.

Criminal justice

The public prosecutor's office provided legal repercussions. More than 500 strikers were charged . They were accused of threat , defamation , abuse or riot . 126 of the accused had been convicted by the end of 1897. The prison sentences totaled over 28 years. There were also 227 fines .

Liberal and Conservative Conclusions

Liberal politicians saw confirmed the need by the strike and its output, arbitration and mediation centers to be made compulsory. With this instrument, the escalation of industrial disputes could be avoided. Conservatives, on the other hand, saw the events as a code for an impending coup . Against this background, consistent measures against social democracy are necessary. General Waldersee considered the violent confrontation of the state with the forces of the coup to be inevitable and advised the emperor in a memorandum not to wait until the state was seriously threatened. Instead, preventive action should be taken against social democracy. At least, however, laws should be passed that make the organization of the masses difficult and that would seriously threaten workers' leaders. Wilhelm II agreed to these considerations and, for his part, called for the destruction of social democracy. In 1899, the State Secretary in the Reich Office of the Interior presented the so-called penitentiary bill to the Reichstag, which was intended to restrict the social-democratic labor movement's ability to act through massive threats of punishment. However, this legislative initiative failed because of the majority in the Reichstag.

Union organization after the strike

The strike leaders regarded it as a deficit that thousands of non-union workers were allowed to have a say in the start and end of the strike. If the right of codecision had been linked to union membership, the strike might have had a more favorable outcome - so the assumption. The worst fear of the strike leaders, which was at the same time the greatest hope of the employers, did not materialize, however: the dock workers did not demoralize their defeat, instead they began to join the union en masse. At the end of 1897 there were over 6,700 members. The showers also gave up their localism and rejoined the port workers' association. The propensity for strikes, however, fell markedly against the backdrop of the defeat of 1897. Furthermore, the repressive measures after the end of the strike shattered union influence among state quay workers. Contrary to the trend, the level of organization fell considerably in this group of workers.

Measures by the Hamburg Senate

The Hamburg Senate did not get involved in the harsh repression policy that Waldersee had advised the Kaiser. Instead, he affirmed the need for gradual social reform . On February 10, 1897, the first measures were taken. The Senate appointed a commission to examine the situation in the port. This working group dealt extensively with the complaints of the workers and also allowed statements by the trade unions, which meant nothing other than their indirect recognition by the state. The final report presented did not spare the readers, but pointed out the grievances in port work. Ferdinand Tönnies described the final report as an ex-post justification for the strike.

Employers implemented some - not all - of the research's suggestions. From then on, wages were no longer paid in the pubs, but in pay offices. The Hamburg Shipowners' Association set up a central proof of work in order to reduce the dependency on landlords and intermediaries. The tariffs for ferry traffic in the port have been reduced. The entrepreneurs also agreed to the proposal to create the post of port inspector.

One of the consequences of the strike was also to tackle the redevelopment of the Gängeviertel. This quarter was not only seen as a place of misery and vice , but also as a haven of political resistance. The renovation, however, dragged on for decades. Initial socio-political considerations to improve the quality of living for the local working population soon no longer played a role, because the economic interests of the landowners, who dominated the Hamburg citizenship, prevailed almost unbroken.

Working conditions, wages, commutes to work

The demand for a limitation of working hours was not enforceable against the entrepreneurs. They also insisted on being able to order night work at any time. Shift work was only introduced in 1907, and excessively long working hours of up to 72 hours were increasingly a thing of the past. In 1912, a normal working day of nine hours was set, but in practice they often worked longer. Physical exertion and the risk of work accidents and permanent health impairments also remained constant companions of port work.

Wages were increased in only a few areas, but not across the board. In many cases there were wage cuts. After 1898 wages stagnated until 1905. Even when they rose thereafter, they lagged behind the rise in the cost of living .

The construction of the Elbe Tunnel in 1911 resulted in a shortening of the way to work. Even more important in the same year was the establishment of the Hamburger Hochbahn , which provided physical relief and considerable time savings on the way between the residential quarters and the workplaces on the Elbe .

Permanent employment and collective agreements

The dockworkers' strike was largely driven by discontinuously employed workers. In the years after the big strike, the entrepreneurs drew the conclusion from this that they would offer permanent jobs in order to secure a higher loyalty of the workers and to strengthen the workers' identification with the activity and the company. At least, however, they wanted to have a workforce who shied away from a strike for longer, because losing a permanent job posed a significantly higher risk than losing a day job. The pioneers of this development were the coal importers and HAPAG, as well as the port companies from 1906, which merged to form the port management association and who managed to bring almost the entire job placement in the port under their control with their proof of work. Before the First World War, this proof of work became a bastion of entrepreneurial power in the port operations and the largest job placement system in Germany.

The entrepreneurs refused to conclude collective bargaining agreements for some time. But finally, starting in 1898, there was a gradual rethink. The power of the trade unions cannot be overlooked, let alone broken. Instead of a fermenting petty war, a labor peace based on collective agreements is the better, because it is more stable and ultimately more cost-effective solution. In 1913 the entire port area was covered by a collective agreement.

Reception after the end of the strike

Contemporary analyzes

The severity of the labor dispute has already prompted contemporaries to write more extensive papers on the dockworkers' strike. This includes the official representation based on police files that Gustav Roscher , Hamburg's police chief shortly afterwards, produced. Carl Legien, on the other hand, described the events from the perspective of the General Commission.

Social science studies were also submitted immediately after the strike. These include the work of Richard Ehrenberg and Ernst Francke and, above all, the representations of the founder of German sociology Ferdinand Tönnies .

research

With a considerable time lag, the strike became the subject of some university theses and dissertations .

The historian Hans-Joachim Bieber has presented two studies on the strike. The first shows the course of the strike and works out the reactions of the Hamburg Senate. The second deals in a compact form with the causes of the strike, the course of the strike and the consequences of the strike. Even Michael Grüttner has released a terse single study on the dock strike. The historian examines the social composition of the port workers, their economic situation and their organizational and strike behavior in order to relate the knowledge gained to the characteristics of the strike. In a further study by Grüttner, his dissertation, the strike action is embedded in a comprehensive examination of the working and living conditions "at the water's edge". Grüttner shows that on the one hand these conditions created underemployment and poverty, on the other hand they also opened up spaces of freedom that were stubbornly defended against the disciplinary demands of industrial work for years. According to Grüttner, the labor dispute of 1896/97 is only one link in a long chain of conflicts between dock workers and entrepreneurs over working conditions and power relations in the port. The study also draws attention to the pronounced ability to deal with conflicts among Hamburg port companies. By the eve of the First World War, they managed to decide all central disputes for themselves, but without being able to finally stop all strike movements and free-trade union counter-power efforts.

Fictionalizations

Georg Asmussen , an engineer at Blohm and Voss for a long time , built the strike into his novel Stürme , published in 1905 , in which the dispute between strikers and strike breakers is discussed in particular. The protagonist Hans Thordsen, himself active on the side of the strikers, criticizes above all that the solidarity principle is exploited and abused by drones who are not willing to work .

The director Werner Hochbaum chose another form of mediation and interpretation of this labor dispute . In 1929 he shot the silent film Brothers in Hamburg , which wanted to recall the events of 1896/97.

attachment

literature

Sources and literature on the strike

- Hans-Joachim Bieber : The strike of the Hamburg port workers 1896/97 and the attitude of the Senate. In: Journal of the Association for Hamburg History , vol. 64 (1978), pp. 91–148. Digitized

- Hans-Joachim Bieber: The Hamburg port workers strike 1896/97. Landeszentrale für Politische Bildung, Hamburg 1987 (reprint from Arno Herzig , Dieter Langewiesche , Arnold Sywottek (ed.): Arbeiter in Hamburg. Lower classes, workers and the labor movement since the end of the 18th century. Publ. Education and Science, Hamburg 1983, ISBN 3-8103-0807-2 ).

- Richard Ehrenberg : The strike of the Hamburg port workers 1896/97. Jena 1897.

- Michael Grüttner : The Hamburg port workers strike 1896/97. In: Klaus Tenfelde and Heinrich Volkmann (eds.): Strike. On the history of the labor dispute in Germany during industrialization. CH Beck, Munich 1981, pp. 143-161, ISBN 3-406-08130-4 .

- Michael Grüttner: "All shipowners stand still ..." Documents on the Hamburg port workers strike. In: Hellmut G. Haasis : Traces of the vanquished. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1984, Vol. 3, pp. 869-887.

- Carl Legien : The strike of the dock workers and seamen in Hamburg-Altona. Presentation of the causes and the course of the strike, as well as the work and wage conditions of the workers employed in port traffic. Publishing house of the General Commission of the German Trade Unions, Hamburg 1897.

- Hannelore Rilke: Labor dispute and public opinion. The Hamburg port workers strike of 1896/97 from a bourgeois-liberal perspective. Scientific term paper to obtain the academic degree of a Magister Artium of the University of Hamburg , Hamburg 1979.

- Johannes Martin Schupp : The social conditions in the port of Hamburg . Inaugural dissertation to obtain a doctorate from the high philosophical faculty of the Royal Christian Albrechts University in Kiel , Kiel 1908.

- Udohaben, Bernt Kamin-Seggewies. Curt Legien: Trials of strength. The workers' struggles against the liberalization of port labor. "The strike of the dock workers and seamen in Hamburg-Altona" from 1896/97. VSA, Hamburg 2007 ISBN 978-3-89965-263-5 .

- Ferdinand Tönnies : Writings on the Hamburg port workers strike. Edited by Rolf Fechner, Profil, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89019-660-2 .

further reading

- Michael Grüttner: The world of work at the water's edge. Social history of the Hamburg port workers 1886–1914 (= critical studies on historical science . Vol. 63). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1984, ISBN 3-525-35722-2 .

- Dieter Schneider: ... so that misery comes to an end. Hundred years of central organization of dock workers. Courier GmbH publishing house, Stuttgart 1990.

Individual evidence

- ↑ For the section “Importance of the Port of Hamburg” see Grüttner, Wasserkante , pp. 19–29.

- ↑ On the importance of the free trade unions and the SPD in Hamburg, see Bieber, Strik, pp. 92 and 95.

- ↑ Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt, p. 25. On the improvement of the employer's association organization immediately before May 1, 1890, see Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt, p. 139 f. For the pioneering role of Hamburg entrepreneurs in the German employer movement, see also Bieber, Strik, pp. 96–98.

- ↑ On the May fights see Grüttner, Arbeitswelt, pp. 137–146 and Bieber, Strik, p. 98.

- ↑ For the prehistory cf. Grütter, dock workers strike, p. 143 f. On the split of the localists see also Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt , pp. 159–164 and Schneider, Elend, p. 24. Schneider, Elend, p. 26 and Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt, p. 159 draw attention to the connection between membership numbers and the cholera epidemic .

- ↑ The mentioned professional groups compare Grüttner, workplace , pp 60-79.

- ↑ Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt (p. 94–101) emphasizes that the predominant structure of casual work in the port was on the one hand a source of unemployment and misery, on the other hand it formed the basis of autonomous behavior that deliberately evaded the constraints of industrial labor economy and its rigid work ethic .

- ↑ These were the workers who were employed on the state quays.

- ↑ Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt , p. 36.

- ↑ On the Baasen see Grüttner Arbeitswelt , pp. 38–42.

- ↑ See Grüttner, Arbeitswelt , p. 147 f.

- ↑ Rilke, Arbeitsklampf , p. 47, states that the degree of organization of the 17,000 dock workers was just under 10 percent.

- ↑ For internal differentiation and the similarities see Grüttner, Hafenarbeiterstreik , pp. 150–155 and Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , pp. 5–7.

- ↑ On the drop in living standards, see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 7 f and Bieber, Strik , pp. 105–107.

- ↑ See the detailed biography in: Rüdiger Zimmermann : Biographisches Lexikon der ÖTV and their predecessor organizations , [Electronic ed.], Library of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung , Bonn 1998.

- ↑ On the successful wage movements of September and October 1896 see Bieber, Strik , p. 112.

- ↑ On the consequences of Mann's expulsion see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 8, Bieber, Strik , p. 109–112 and Schneider, Elend , p. 31 f.

- ↑ For the development of the first strikes of the showmen up to November 20, 1896 see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 8 f and Grüttner, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 144 f.

- ↑ For the details of these demands with different groups of workers see Legien, Strik , pp. 15–39.

- ^ Rolf Geffken : Jammer and Wind: an alternative history of the German shipping industry , Hamburg 1985, p. 28.

- ↑ Figures from Bieber, dock workers strike , pp. 9 and 11; Grüttner, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 145. For the sequence of stoppages by the individual occupational groups, see Legien, Strik , p. 48, Rilke, Arbeitsskampf , p. 58 and Schneider, Elend , p. 34 et seq., Legien and Schneider also have figures on growth the number of strikers.

- ↑ For the leadership of the strike, see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 9 and Grüttner, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 145. For further measures, see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 9.

- ↑ For the reaction of the trade unions abroad and international solidarity with the Hamburg port workers, see Bieber, Strik , pp. 115–117.

- ↑ On the solidarity of the National Social Association with the Hamburg port workers see Dieter Düding: Der Nationaloziale Verein 1896–1903. The failed attempt at a party-political synthesis of nationalism, socialism and liberalism. Oldenbourg, Munich 1972, ISBN 3-486-43801-8 , p. 109 ff.

- ↑ For information on donations and strike money, see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 9 f. For the historical significance of the support intensity, see Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt , p. 171.

- ↑ See the overview of wages and groups of dock workers at Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt , p. 51. Reference to the amount of the support rates of the poor institution at Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt , p. 169.

- ↑ See Grüttner, Arbeitswelt , p. 173 f.

- ↑ On the balance of power in the employers' camp, see Grüttner, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 146 f.

- ^ Number of strike breakers at Rilke, industrial action , p. 59.

- ↑ On the recruitment of strike breakers and their productivity, see Grüttner, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 147 and Bieber, Strik , p. 127.

- ↑ For the reaction of the emperor see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 11. There also the quote.

- ↑ For the opinion of Boettichers and the solidarity address from other employers' associations, see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 11. There also the quotation from the "Association of German Iron and ...". For the origin of the wage tables on which Boetticher relied, see Rilke, Arbeitsskampf , p. 71. Legien has already commented in detail on the “wage list fraud”. See Legien, Strike , pp. 12-15. On the words of Stumm-Halberg see Bieber, Strik , p. 124.

- ↑ For the Senate's initial position, see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 10.

- ↑ Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 10. Grüttner, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 148 falsely writes that the commission should have consisted of four representatives each of the workers, the employers and the three initiators. The call for mediation by the three personalities is reproduced in Legien, Strik , p. 50.

- ↑ On the failure of this first arbitration initiative see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 11. The employers' response to the proposal to set up an arbitration tribunal is printed in Legien, pp. 51–53. Here also the word of the "power struggle".

- ↑ Here briefly Rilke, industrial action , p. 50 f.

- ↑ For the development from December 4th to 9th, 1896 see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 12 f.

- ↑ The explanation is reproduced in Legien, Strik , p. 60.

- ↑ On the radicalization of the strike, see Grüttner, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 148 f.

- ↑ On this, Grüttner, dock workers strike , p. 147 and Bieber, dock workers strike , p. 13.

- ↑ For the development from December 16 to 19, 1896 see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 13 f.

- ↑ For the machinists 'self-image and organizational behavior, see Grüttner, Arbeitswelt , pp. 71 f, 134 f, 153 f and 249. For the significance of the machinists during the dock workers' strike, see Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt , p. 168 and also Legien, Strike , p. 64.

- ↑ For the development over the turn of the year see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 14.

- ↑ For the tradition of this demand see Schneider, Elend , p. 28.

- ↑ For the history and the implementation of the meeting in the stock exchange, see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 14 f and Bieber, strike , p. 137–140.

- ↑ Tönnies , the founder of sociology in Germany, who also published several articles on the dockworkers strike, his statements cost him a professorship for years.

- ↑ On the "Professors Call" see Düding, National Social Association , p. 110.

- ↑ Roscher, quoted in Bieber, Strik , p. 141 and Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 15. The Bieber judgment has not been contradicted.

- ↑ For the meaning of the “Professors Appeal” see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 15 and Bieber, Strik , p. 140 f. This appeal is reproduced in Legien, Strik , p. 70. For the criminal repression against the bourgeois social reformers see Rilke, Arbeitsskampf , p. 79 f and Bieber, Strik , p. 141, note 276.

- ↑ On the absence of the thaw and the reduction of the strike fee, see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 15 and Bieber, Strik , p. 142.Bieber dates this reduction, which is given in Legien, Strik , p. 75, for January 26th, on January 21, 1897.

- ↑ On the strikers, see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 15 and Grüttner, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 149.

- ↑ On the excesses cf. Grüttner, dock workers strike , p . 149 and Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt , p. 173 f and Legien, strike , p. 85 f. Grüttner makes it clear that a large number of strikers were involved in the riots, which Legien had denied for tactical reasons in his paper on the dock workers' strike in order to prevent these riots from being exploited for anti-union agitation.

- ↑ On this, Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 15, there also the quotations.

- ↑ On these repression after the strike, see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 15 f. For the change in the office of quay director and the consequences, see Grüttner, Arbeitswelt , p. 67 f.

- ↑ Figures from Bieber, dock workers strike , p . 16 and Bieber, strike , p. 144.

- ↑ On the liberal and conservative reactions, see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 16. On Waldersee's proposals, cf. also Grüttner, dock workers strike , p. 155 f.

- ↑ On the aftermath of the strike on the union organization and on the discussion about decision-making rights for the unorganized see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 16 and Grüttner, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 158 f. For details on this, Grüttner, Arbeitswelt , pp. 176–196.

- ↑ On this, Grüttner, Wasserkante , p. 183 f.

- ↑ On the Bieber Senate Commission, Dockworkers Strike , p. 16.

- ↑ On the relief for the workers, which the employers have supported, see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 16 f.

- ↑ On this, Grüttner, Arbeitswelt , pp. 114–123.

- ↑ For the duration of work and the side effects of port work after 1897, see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 17.

- ↑ On wage developments see Grüttner, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 156, Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt , pp. 48–56 and Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 17.

- ↑ On the effects of the improved transport infrastructure, see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 17.

- ↑ The Stauer-Baase divided the workers with these cards into three groups. The "permanent" workers, equipped with blue cards, were generally preferred - and not just as before in a single company. Unemployed workers received brown cards. Occasional workers were given white slips of paper. They only got work when the reserves of the first two categories of workers were exhausted. See Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt , p. 181.

- ↑ On the development towards permanent jobs see Grüttner, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 157, Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt , pp. 179–183 and Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 17. See also the explanations in Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt , pp. 210–220 on so-called contract work and to the proof of work of the port operating association. Grüttner assesses the importance of this proof of work much more critically than Bieber ( Strik , p. 147), who sees a reduction in the potential for conflict and does not illuminate the non-equal power and decision-making relationships in committees of this proof of work.

- ↑ On the gradual triumph of the collective agreement, see Bieber, Hafenarbeiterstreik , p. 17 and Bieber, strike , p. 147.

- ^ The strike of the Hamburg port workers in 1896/97. Official representation based on the files of Department II (political and criminal police) of the Hamburg police authority , Lütcke & Wulff, Hamburg 1897.

- ↑ See the section “Literature” and the references to Ehrenberg, Francke and Tönnies in Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt , pp. 319 and 326.

- ↑ See the exemplary evidence in Rilke Arbeitsskampf , p. 1 and p. 93 as well as in Grüttner, Arbeitsswelt , p. 291 f, note 114.

- ↑ See Bieber, strike and Bieber, dock workers strike .

- ^ Grüttner, dock workers strike .

- ↑ Grüttner, Working World .

- ↑ Information about the film on filmportal.de ( Memento of the original from July 28, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ^ Contains: Carl Legien: The strike of the dock workers and seamen in Hamburg-Altona . Hamburg 1897.

Web links

- Bernhard Röhl: "Ditmal strict wi för wat anneres" - article in the daily newspaper of March 11, 2002 about the Hamburg dock workers strike of 1896/97