Longobards

The Langobards ( Latin Langobardi , Greek οἱ Λαγγοβάρδοι , also Winniler ) were part of the tribal group of the Suebi , closely related to the Semnones , and thus an Elbe Germanic tribe that originally settled on the lower Elbe .

Surname

It is unclear where the name of the Lombards comes from. The "Langobardi" at Strabo ( Die Geographie VII, 1,3) are regarded as the first mention. The Lombard chronicler Paulus Diaconus tells of an old legend in the 8th century (see Origo gentis ). Accordingly, the Lombards were once called Winniler. These were threatened by the vandals , and both peoples prepared for battle. The Vandals prayed to Wodan , and he told them that victory would be given to those he saw first in the morning. Gambara , mother of the Vinnillian dukes Ibor and Agio, advised to pray to the goddess Frea , Wodan's wife. Frea gave instructions that the Winnil women should line up in the east early in the morning and tie their long hair like beards in front of their faces. Early in the morning Frea got up early and turned Wodan's bed to the east, and when he woke up he saw the Winnilerinnen and asked astonished: “Who are these long beards?” Then Frea replied: “You gave them their name, now give them the victory ! ”So the Winnil triumphed over the Vandals, and since then they have called themselves Lombards.

The derivation of the name is also controversial in research. It is clear that the description of Paulus Diaconus contains topical elements, especially since the long beard dress was not a special characteristic only of the Lombards. Nevertheless, even in more recent research, the derivation of Longobards from long beards is considered quite probable for philological reasons, whereby an original external name is assumed. An alternative name for a tribal battle ax considered in research is viewed as more problematic.

history

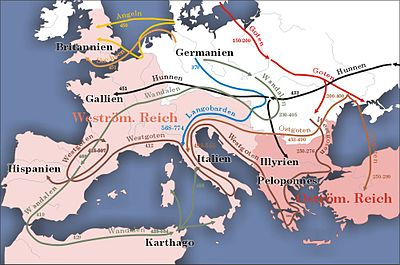

The early history of the Lombards has often been misinterpreted due to inadequate notions of closed, wandering peoples. The question of whether groups of this name on the lower Elbe in the late 1st century BC BC with the groups mentioned further south from the 5th century and migrating to Italy from 568 onwards - even genetically - is considered to be a research mistake.

Groups called Lombards were identified by Strabo and Tacitus for the year 3 BC. Mentioned as part of the Marbod League. During a campaign of Tiberius to the Elbe in 5 AD, which took place in the course of the immensum bellum , the Lombards are mentioned again: The historian Velleius Paterculus wrote “The power of the Lombards was broken, a tribe that was even wilder than the Germanic Wildness is. ”Strabon mentions that the Lombards, who actually settled on the left (southern) bank of the Elbe, moved to the right (northern) bank of the Elbe. This seems to be supported by the abandonment of the occupancy of local cemeteries. With the subsequent retreat of the Romans to the Rhine , the Lombards disappeared from history for the next 150 years. Archeology shows a group of finds known as Elbe Germanic on both sides of the lower and middle Elbe and in Bohemia .

The Lombards invaded the Roman Empire in AD 166 at the beginning of the Marcomann Wars as part of a raid . After the Marcomann Wars, archaeological findings show that the focus of settlement shifted from Mecklenburg to the Altmark in the west of the Elbe . Archaeologically as Elbgermanen identifiable populations occupied the area from 250 to 260 on the middle Danube , where previously the Rugier settled (today Lower Austria); under King Godeoc in 489 these were also the Lombards, who settled on the left bank of the Danube between Linz and Vienna. Around 490 a group, which the sources call the Lombards, moved to Moravia and at the beginning of the 6th century to Pannonia , more precisely to the Tullnerfeld . In 510, under their leader Tato, they finally destroyed the Herul empire ruled by Rudolf . Under the subsequent King Wacho , the Lombards moved to Pannonia ( Pannonia inferior ); under Audoin in 546/47 the settlement also took place in the Pannonia Secunda and thus in all of western Hungary and in the area of today's Burgenland . This settlement was supported by the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I , as he assumed from the Lombards that they would keep the Gepids living east of the Danube in check and also form a security belt against the Ostrogoths in Italy and the Franks in former Gaul. The Lombards also undertook raids to pillage Dalmatia and Illyria and came as far as the Byzantine Epidamnus .

However, it is uncertain whether a Lombard population really existed in the period between the Lombards' phase on the lower Elbe, which is handed down in ancient sources, and their appearance on the central Danube. Perhaps it was only on the Danube that a constantly re-mixing population group was newly formed in disputes with the Herulers. A large group of Saxons who joined the Lombards appears in the sources. According to this interpretation, it took on an old, well-known and glorious name. According to Prokop, Emperor Justinian I left the Lombards “the Pannonian fortresses and the Noric polis”. In 552, many Longobard warriors accompanied the Eastern Roman military leader Narses to Italy to fight the Ostrogoths . However, they were soon released due to their lack of discipline. They also provided auxiliary troops on the move against the Persians.

In the year 567 the Lombards destroyed the Gepid Empire after long battles together with the Avars . Already in the following year most of the Lombards moved to Italy, accompanied by Gepids, Thuringians, Sarmatians, Suebi, Pannonians and Norikers. Whether they had to give way to Avar pressure, as was generally assumed in the past, whether they had the rich peninsula in view from the outset or were even invited by Narses, is disputed. In any case, from April 2, 568, under King Alboin, they conquered large parts of Italy, which they had got to know in 552 as a still relatively rich country. Together with other Germanic tribes, they pushed further south, but were unable to conquer the entire peninsula: about half of the country remained under the control of the Eastern Roman Empire.

The Lombard conquest of Italy is considered to be the last train of the late ancient migration and therefore a possible date for the end of antiquity and the beginning of the early Middle Ages in this area. The most important Longobard settlement areas in Italy can be identified on the basis of the burial grounds. These were mainly concentrated in the areas north of the Po from Piedmont to Friuli , in the area between Lake Maggiore and Lake Garda (the Ostrogothic settlement was already concentrated here before 550). Towards the south one encounters significantly fewer burial grounds. The majority of the Lombards resident in Italy adopted Arian Christianity. The Longobard Empire with the capital Pavia comprised northern Italy and parts of central and southern Italy. It was divided into several ducats (partial duchies).

How large the number of Lombards immigrated to Italy cannot be precisely determined in view of the unfavorable sources. Estimates assume around 100,000 to around 150,000 people, including other ethnic groups who had joined the Longobard tribal core (including Saxons and remains of the Gepids). The figure of 500,000 people named by the Lombard historian Paulus Diaconus is probably unrealistic, as is not infrequently the case with figures from ancient and medieval authors. Just supplying such a huge wandering crowd would have encountered insurmountable obstacles. Paulus Diaconus alone counted 20,000 Saxon men who accompanied the Lombards to Italy, which, according to Wilfried Menghin , suggests that at least 40,000 people set out with them. He also assumes that the total number of Longobards should be estimated at least three times as large as that of the Saxons. Walter Pohl came to around 100,000 immigrants in 2009. The Longobard procession started from the west bank of Lake Balaton and moved via Emona and then to Kalce and on to Aidussina and Savogna to Cividale del Friuli , without encountering much resistance. The Bishop of Tarvisium met them near Spresiano and gave Albion the keys to the city of Treviso , which was elevated to a Lombard duchy. The route to Vicenza and Verona , which he reached at the end of October 568, probably led on the old Roman road . In this way he founded four duchies (Cividale - here he put his marpais (marshal) and nephew Gisulf, Ceneda , Treviso and Vicenza). In 569 he founded other duchies in Brescia and Bergamo . Milan was captured on September 3, 569. From here the duchies of Turin and Asti were founded , probably to ward off possible attacks by the Franks. Ewin was given the Duchy of Trento . It went on via Liguria and Tuscany to Pavia . This city put up bitter resistance and could not be conquered until 572. The duchies of Benevento and Spoleto were founded in central and southern Italy . Alboin was murdered on June 28, 572 (or 573) in his capital, Verona.

After Alboin's murder, Cleph followed, but was also murdered after a short time (574). After his murder, no king was elected for ten years ( interregnum ), during which the various dukes led a mostly violent regime. Then Cleph's son, Authari (584-589), was elected king. He married Theudelinde , daughter of the allied Duke Garibald I of Bavaria . After Authari's death, the Catholic Theudelinde married Agilulf , who was an Arian himself but, under the influence of his wife, sought rapprochement with the Catholic Pope in Rome. He allowed some of the bishops who had fled the Lombards to return, and he also returned church property he had taken possession of. It was not until 662 that Catholicism finally ousted Arianism from among the Lombards, who dominated the Catholic indigenous majority of the population. Presumably the Lombards also gave up their common language at this time and quickly and completely integrated into the Roman population. In research, the Lombard invasion, with which the peninsula lost its political unity for 1300 years, usually marks the point from which one can speak of "Italian" instead of "Italian" (as in antiquity).

At the end of the 7th century there was a civil war in which Cunincpert was able to prevail against Alahis .

Under Grimoald (662–671) and Liutprand (712–744) the Longobard Empire reached its greatest spatial extent. Charlemagne conquered Pavia in 774 under the last Longobard king Desiderius and had himself crowned King of the Longobards (→ Longobard campaign ).

In the south, the Duchy of Benevento remained independent under Arichis II , who assumed the title of princeps and ruled from 774 with equal power. Occasionally there was still resistance to Karl's rule. Hrodgaud , the dux (Duke) of Friuli , claimed the Lombard crown for himself in 776 and several cities joined him. He was quickly defeated and killed by Charlemagne, who came to Italy in forced marches. Desiderius' son Adelchis also tried to regain the Lombard royal crown, but ultimately failed in 788 when his Byzantine troops landed in Calabria from Grimoald III. , the dux of Benevento, were beaten.

The Lombard language became extinct by 1000. With the conquest by the Normans in the 11th century, the ducat Benevento also lost its independence. The name "Lombards" has been preserved in the name of the northern Italian region of Lombardy ( Lombardia in Italian ).

The royal crown of the Lombards was the Iron Crown . Numerous Roman-German rulers of the Middle Ages, such as Conrad II , Henry VII or Charles IV , were crowned with it in order to underline their claim to imperial Italy . Centuries later, Napoleon I had himself crowned King of Italy with the iron crown in order to legitimize his rule.

Ruling structure

By the 8th century, an administrative structure had developed at the head of which the rex ( king ) stood. He was responsible for the iudices ("judges", senior officials), which were made up of the duces (dukes) and gastalden or comes (" Pfalzgrafen ", counts ). The office of dux was conferred for life, often hereditary, while the Gastalden were often changed after some time. The iudices were subordinate to the actores ("managing directors", sub-officials), which are divided into sculdahis ( Schultheiss , also rector loci ), centenarius (Zentgraf, Gograf ) and locopositus (local superior) without their distinguishing feature clearly coming to light . One level lower in the hierarchy were the decani (chiefs), saltarii (“pasture” supervisors) and scariones , oviscariones and scaffardi (superiors of a “crowd”) who, as subordinate officials, tended to perform “police” tasks.

As gasindi 'royal court officials' there was the marpahis or strator ' marshal , stable master ', the stolesaz or maior domus ' chamberlain ', vesterarius ' treasurer ' and spatharius 'sword bearer', while the cupbearer, otherwise important at Germanic courts, apparently only belonged to the Lombards played a subordinate role. The referendarius ' clerk ' also held an important court office.

Language and culture

Longobard was spoken by the Longobards who immigrated to northern Italy from the 6th century to the beginning of the 11th century. Essentially only personal names, place names and individual words that appear in the early days as runic inscriptions and later in Latin documents have survived. It is generally assumed that the Longobard grammar largely corresponded to the structures of Old High German.

From a cultural point of view, the rule of the Germanic Lombards, which were still relatively uncivilized, initially meant a considerable setback in northern Italy, which had been influenced by late ancient and above all Byzantine art and culture.

The main element of the Lombard-Arian art, which originated from Germanic ornamental geometry, was the braided ribbon ornament, which brought it to a true perfection.

The Lombard rulers, however, like the Catholic religion, increasingly adopted the Latin language and adapted the Roman and Byzantine cultural influences. The old Roman school system is also said to have flourished under the Lombard kings. They had already come into contact with Byzantine art in Pannonia. They added new stylistic elements to the Byzantine structures of the basilica and the central building , in particular the decoration of the outer walls with blind arcades , pilasters or pilaster strips and arched friezes . The Byzantine architectural style was further developed and, as the "Lombard" style , it flourished and spread in Western Europe.

A number of churches and monasteries as well as grave goods have been preserved as traces of the cultural achievements of the Lombards .

Law and justice testify to the Lombards' lively will to order. In Edictus Rothari 643 - the first codification of a Germanic law that was already heavily influenced by Roman - King Rothari recorded and standardized the Lombard law , a customary law that has been passed down orally , in Latin.

The historian Paulus Diaconus wrote the “History of the Lombards”, among other things, under the rule of Charlemagne.

Since Bruno Schweizer, some researchers have assumed with the Longobard theory of Cimbrian that the last remnants of the Longobards live on in today's Cimbri and their ancient language. However, this thesis is very controversial and has few advocates today. In German studies, the thesis is also sometimes put forward that Lombard influence caused the second sound shift around 600 , through which the southern, High German dialects separated from the northern, Low German. According to their proponents, this thesis is supported by the fact that one of the earliest evidence of the sound shift can be found in the Edictus Rothari , which was written down in 643 . In the opinion of other researchers, there is still insufficient evidence for this hypothesis - if only because of our ultimately inadequate knowledge of Langobard.

Dukes of the Lombards

Note: The first dukes as far as Wacho cannot be documented historically; they are only contained in the tribal saga. The reigns up to Alboin are not secured.

- ??? - ??? Ibor and Agio (also Aio)

- ??? - ??? Agelmund (son of Agio; from the family of Gugingus)

- ??? - ??? Lamissio (also Laiamicho; from the Gugingus family)

- ??? - ??? Lethuc (also Lethu)

- ??? - ??? Hildeoc (also Hildehoc, Aldihoc; son of Lethuc)

- ??? - ??? Godeoc (also Godehoc)

- 478–490 Claffo (son of Godeoc)

- 490-510 Tato (son of Claffo)

- 510-540 Wacho (son of Unichi, nephew of Tato)

- 540-545 Walthari

- 545-560 Audoin

- 560-572 Alboin

Kings of the Lombards

(Lombardy, Italy)

- 568-572 Alboin

- 572-574 Cleph

- 574-584 Interregnum

- 584-590 Authari

- 590-615 Agilulf

- 615-626 Adaloald

- 626-636 Arioald

- 636-652 Rothari

- 652-653 Rodoald

- 653-661 Aripert I.

- 661–662 Godepert and Perctarit

- 662-671 Grimoald

- 671 Garibald

- 671-688 Perctarit (2nd time)

- 688-700 Cunincpert

- 700-701 Liutpert

- 701 Raginpert

- 701 Rotharit (dux from Bergamo)

- 701-712 Aripert II.

- 712 claim

- 712-744 Liutprand

- 744 Hildeprand

- 744-749 Ratchis

- 749-756 Aistulf

- 756-757 Ratchis (2nd time)

- 757-774 Desiderius (last Longobard king of the Longobards)

- 774–781 Charlemagne in personal union

- 781-810 Pippin

- 810–812 Charlemagne (2nd time) in personal union

- 812-818 Bernhard

- 818–822 Ludwig the Pious

- 822–855 Lothar I in personal union

- 844–875 Ludwig II.

The list ends here, because with Ludwig II the office of Duke of the Lombards was merged with that of King of Italy - a title that Ludwig had already received from his father in the year 839/840.

UNESCO World Heritage Site

Since June 2011 a group of important buildings under the title The Lombards in Italy, Places of Power (568 to 774 AD) has been included in the UNESCO World Heritage List. The buildings contain the most important monumental testimonies of the Lombards, which can be found in seven different locations on Italian soil. These are Cividale del Friuli , Brescia , Castelseprio Torba , Spoleto , Campello sul Clitunno , Benevento , Monte Sant'Angelo . They extend from the north of the peninsula to the south, where the dominions of the most important Lombard duchies were.

literature

Overview works

- Panagiotis Antonopoulos: Early Peril Lost Faith: Italy between Byzantines and Lombards in the Early Years of the Lombard Settlement, AD 568-608. Lambert, Saarbrücken 2016.

- Volker Bierbrauer , Christoph Eger, Robert Nedoma , Walter Pohl , Piergiuseppe Scardigli, Jürgen Udolph : Longobards. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 18, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2001, ISBN 3-11-016950-9 , pp. 50-93. (Professional article)

- Urs Müller: Longobard legends. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 18, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2001, ISBN 3-11-016950-9 , pp. 93-102. (introductory article)

- Jan Bemmann, Michael Schmauder (ed.): Cultural change in Central Europe, Lombards - Avars - Slavs. Files from the international conference in Bonn from February 25 to 28, 2008. RGK. Colloquia on Pre- and Early History Volume 11. Bonn 2008.

- Karin Priester : History of the Longobards . Society, culture, everyday life. Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8062-1848-X (lively, well-illustrated introduction).

- Jörg Jarnut : History of the Longobards. In: Urban paperbacks. Volume 339, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-17-007515-2 (scientific, not unproblematic introduction).

- Neil Christie: The Lombards . The Ancient Longobards. Blackwell, Oxford 1995, ISBN 0-631-18238-1 .

- Walter Pohl , Peter Erhart (Ed.): The Longobards. Domination and identity. In: Research on the history of the Middle Ages. Volume 9. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 2005 (research status of the Langobardistik).

Exhibition catalogs

- Berthold Schmidt : The late migration period in Central Germany. Catalog (north and east part). In: Publications of the State Museum for Prehistory in Halle. 29th Berlin 1975.

- Landschaftsverband Rheinland, Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn (publisher); Morten Hegewisch (editor): The Lombards. The end of the Great Migration. Catalog for the exhibition in the Rheinisches LandesMuseum Bonn, August 22, 2008 - January 11, 2009. Primus, Darmstadt 2008, ISBN 978-3-89678-385-1 .

origin

- Hermann Fröhlich: On the origin of the Lombards. In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries . 55/56 (1976) 1-21 ( online ).

- Ralf Busch (Ed.): The Longobards. From the Lower Elbe to Italy. In: Publication by the Hamburg Museum for Archeology and the History of Harburg. (Helms Museum). Volume 54.Wachholtz, Neumünster 1988, ISBN 3-529-01833-3 .

archeology

- Wilfried Menghin : The Lombards. Archeology and history. Theiss, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-8062-0364-4 (History of the Lombards from an archaeological-historical perspective).

- Volker Bierbrauer: The Lombards' conquest of Italy from an archaeological point of view. In: Michael Müller-Wille, Reinhard Schneider (Ed.): Selected problems of European land grabbing in the early and high Middle Ages. Sigmaringen 1993, pp. 103-172.

- Uta von Freeden, Tivadar Vida: excavations of the Longobard burial ground of Szólád, Somogy county, Hungary. In: Germania. Volume 85, 2007, pp. 359-384.

External relations

- Konstantinos P. Christou: Byzantium and the Longobards . From the settlement in Pannonia to final recognition (500–680). Historical Publications St. D. Basilopoulos, Athens 1991, ISBN 960-7100-38-7 (German and Greek).

- Paolo Delogu among others: Longobardi e Bizantini. In: Paolo Delogu; André Guillou; Gherardo Ortalli; Giuseppe Galasso (Ed.): Storia d'Italia , Volume 1. UTET, Torino 1995, ISBN 88-02-03510-5 (Italian).

swell

- Gert Audring (collaborator), Joachim Herrmann (ed.): Greek and Latin sources on the early history of Central Europe up to the middle of the 1st millennium of our era, 1st part. In: Writings and Sources of the Old World. Volume 37.2. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-05-000348-0 (source collection).

Web links

- Reto Marti: Longobards. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Les Lombards, derniers barbaren du monde romain par Jean-Pierre Martin, Directeur de recherche au CNRS.

- Sources on the Longobard history . (Latin texts on the history of the Lombards and Italy in the early Middle Ages)

- National Archaeological Museum of Cividale de Friuli . (Images of found objects of Lombard art)

- Paulus Diaconus: History of the Langobards (English)

- Lecture by Caterina Giostri: Goti e Longobardi in Italia. Le potentiali dell'archeologia in riferimento all'identità , Padua 2010 (Italian).

Remarks

- ↑ Strabo mentions Lankosargen (Greek: οι Λαγκόσαργοι), probably another expression for the Longobards.

- ↑ Lombards. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Volume 18, p. 50.

- ↑ Lombards. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Volume 18, pp. 50f.

- ↑ Robert Nedoma: Old Germanic anthroponyms. In: Dieter Geuenich , Wolfgang Haubrichs and Jörg Jarnut (eds.): Person and Name. Methodical problems in the creation of a personal name book of the early Middle Ages (= supplementary volumes to the Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Volume 32). Berlin / New York 2002, pp. 117f.

- ↑ Wilfried Menghin : The Longobards. Archeology and History , Theiss, Stuttgart 1985, pp. 15-17.

- ↑ Strabo 7, 1, 3; Velleius 2, 108, 2; 2, 109, 2f .; Tacitus, Annals 2, 45, 1.

- ↑ Velleius 2, 106; 2, 109, 1f.

- ^ Strabo, Geographika 7, 1, 3.

- ↑ The Lombards. The end of the mass migration, p. 57f.

- ↑ Karin Priester: History of the Longobards. Society - culture - everyday life . Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, p. 23.

- ↑ Karin Priester, 2004, p. 28.

- ↑ Walter Pohl: The Lombards between Elbe and Italy. In: The Lombards. The end of the Great Migration. Catalog for the exhibition in the Rheinisches LandesMuseum Bonn, August 22, 2008– January 11, 2009. Primus, Darmstadt 2008, pp. 23–33, here: p. 26.

- ↑ Max Spindler: Handbook of Bavarian History. Volume 1: The old Bavaria, the tribal duchy up to the end of the 12th century , Beck, Munich 1981, p. 121 (refers to "Paulus Diac. II 26, p. 87" (note 26)).

- ↑ Wilfried Menghin : The Longobards. Archäologie und Geschichte , Theiss, Stuttgart 1985, p. 95, thinks that one could even assume up to 200,000.

- ↑ Walter Pohl: The Lombards between Elbe and Italy. In: The Lombards. The end of the Great Migration. Catalog for the exhibition in the Rheinisches LandesMuseum Bonn August 22, 2008 - January 11, 2009. Primus, Darmstadt 2008, pp. 23–33, here: p. 29.

- ↑ Karin Priester: History of the Longobards. Society - culture - everyday life . Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, p. 37 ff.

- ↑ Hartmann: History of Italy in the Middle Ages Volume II Part 2, Perthes, Gotha 1903, p. 285ff.

- ↑ Franconian Reichsannals.

- ↑ The terms in brackets only give the approximate meaning and cannot be equated with the early medieval offices.

- ↑ a b c Thomas Hodgkin: Italy and Her Invaders . Volume VI. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1897, pp. 578 f.

- ^ Ludo Moritz Hartmann : History of Italy in the Middle Ages, Volume II, Part 2. Perthes, Gotha 1903, pp. 37-40.

- ^ Ludo Moritz Hartmann : History of Italy in the Middle Ages, Volume II, Part 2. Perthes, Gotha 1903, pp. 47-48.

- ↑ Bruno Schweizer: The origin of the Zimbern

- ↑ Florus van der Rhee: The high German sound shift in the Langobardischen laws