Maria Sibylla Merian

Maria Sibylla Merian (born April 2, 1647 in Frankfurt am Main , † January 13, 1717 in Amsterdam ) was a naturalist and artist. She belongs to the younger Frankfurt line of the Merian family from Basel and grew up in Frankfurt am Main.

She received her artistic training from her stepfather Jacob Marrel , a student of the still life painter Georg Flegel . She also lived in Frankfurt until 1670, then in Nuremberg , Amsterdam and West Friesland . The governor of Suriname , Cornelis van Sommelsdijk, suggested that she undertake a two-year trip to this Dutch colony from 1699 onwards . After returning to Europe, Maria Sibylla Merian published her main work Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium , which made the artist famous.

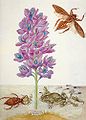

Because of her precise observations and representations of the metamorphosis of butterflies , she is considered an important pioneer of modern entomology .

To the prehistory

For the scholars of the Middle Ages , the nature that surrounded them was hardly worth considering. In this respect they adopted what was handed down from antiquity - including Aristotle's idea of the nature of insects. After that, these “unworthy” animals had arisen in a kind of spontaneous generation from rotting mud - a doctrine that was not convincingly refuted until 1668 by Francesco Redi . A few decades earlier, two books on insects had appeared that are considered to be the first documents in entomology: De animalibus insectis libri septem by Ulisse Aldrovandi (Bologna 1602) and Insectorum sive minimorum animalium theatrum by Thomas Moffett (London 1634), a work that also refers to earlier ones Considerations by the Zurich naturalist Conrad Gessner supported. The publisher of Matthew Merian , the father of Maria Sibylla, brought in 1653, the Historiae naturalis de insectis libri III of educators and polymath John Johnston out mainly a compilation of footage from the work of Moffett and Aldrovandi, whose relatively coarse woodcuts now in detailed engravings implemented were.

The large, complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts by Johann Heinrich Zedler (1706–1751) initially defines under the keyword Insectum : "Vermin in general, which means all, warring and flying species," then points to bees and silkworms the economic benefit of entomological studies, but also emphasizes the spiritual benefit: “… yes, there is no worm so hideous and so small in our eyes that, if we only wanted to turn our due attention to it, we would not like the wisdom of the great Baumeister's Heaven and Earth was completely convincing. ”In conclusion, it is assumed that not many people would be suitable for this new field of research:“ But this requires a particularly tough diligence, deep reflection and an arduous realization, which, however, is very little given to them. ”

The late renaissance marked the beginning of flower and still life painting , which has been cultivated especially in the Netherlands since the beginning of the 17th century and flourished as an independent art form during the Baroque era . Maria Sibylla's grandfather Johann Theodor de Bry had already published a copper engraved volume with 80 depictions of flowers in 1612, her father Matthäus Merian provided an expanded new edition of this Florilegium novum in 1641 . The life's work of Maria Sibylla Merian was created in a time of increasing interest in nature, its closer observation and its subtle, artistic representation.

Life

Frankfurt am Main

Maria Sibylla Merian was born in 1647 as the daughter of Matthäus Merian the Elder and his second wife Johanna Catharina Sibylla Heim. Her half-brothers were Matthäus Merian the Younger and Caspar Merian . Her father was a publisher and engraver in Frankfurt, editor of the Theatrum Europaeum and the Topographien, and well-known for his frequently reproduced cityscapes. When his daughter was born, he was 54 years old and ailing. He died just three years later. In the following year the widow married the flower painter Jacob Marrel , a pupil of the Flemish school of painting, who set up a studio in Frankfurt, but continued his flourishing art trade in Utrecht and rarely stayed with his family.

The artistic talent of Maria Sibylla became clear very early, but found no support from her petty-bourgeois, strict and amusic mother. So she secretly practiced copying existing art sheets in an attic. Finally, her stepfather Marrel advocated and supported targeted artistic training; because of his frequent absence he commissioned one of his students, Abraham Mignon (since 1676). At the age of 11 Maria Sibylla Merian was able to produce copperplate engravings; she soon surpassed her teacher in this technique and developed a personal style of painting. She complemented her flower pictures with small butterflies and beetles, following the example of the Utrecht School of Painting.

During this time, she began breeding silkworms , but soon expanded her attention to other species of caterpillars. In the foreword to her famous late work on the Surinamese insects ( Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium ) she wrote in retrospect:

“I have been researching insects from a young age. First I started with silkworms in my hometown Frankfurt am Main. Then I found out that other caterpillar species developed much nicer butterflies and owls than silkworms. This prompted me to collect all the caterpillar species I could find to watch their transformation. Therefore I withdrew from all human society and dealt with these investigations. "

With her special interest, the teenage researcher explored uncertain territory, which caused her mother to fear and unease. Maria Sibylla herself was increasingly committed, recorded the metamorphoses of the butterflies and their typical environment in her sketchbook , but not only observed her insects with an objective, inquiring look, but also with religious reverence for what she experienced as the miracle of creation . These two aspects, combined with artistic intensity, characterize her entire life's work and can also be found in the text accompanying her books.

On May 16, 1665 Maria Sibylla Merian was married to Johann Andreas Graff (1637–1701); he too was a student of her stepfather, Marell. In the third year of marriage, the first daughter, Johanna Helena, was born.

Numerous very detailed drawings and copperplate engravings of Nuremberg church interiors and other buildings are known by Johann Andreas Graff, including a splendid volume with views of Nuremberg. In a resolution of 1685, the Nuremberg Council praised “his good change that he has conducted here, also in his knowledge and the information he has given to the youth”. Apparently he worked as a drawing teacher - it is known that he was the first to teach the baroque master builder Johann Jacob Schübler in childhood. The frequently found representation in some texts about Maria Sibylla Merian that Graff was not up to his wife, professionally unsuccessful, plagued by feelings of inferiority or even drunk, cannot be proven.

Nuremberg

In 1670 the family moved to Nuremberg, the city of Graff's birth . Maria Sibylla had to contribute through a variety of activities to secure her livelihood. However, as a woman in the Free Imperial City of Nuremberg, she had narrow professional limits. The “Painter's Order” from the end of the 16th century only allowed men to paint with oil paints on canvas and thus secured them those jobs that promised prestige and good income. Women were only allowed to work in small formats, with watercolor and opaque colors on paper or parchment . The main source of income for the family was the trade in paints, varnish and painting utensils, which Maria Sibylla Merian operated. She also took on a large number of commissioned work, for example embroidering silk blankets or painted table cloths for the town's patrician households .

She also taught young women the art of flower painting and embroidery. Her students included Clara Regina Imhoff (1664-1740), through whom she gained access to the Hesperides Gardens of the Imhoff patrician family, and the later successful flower painter Magdalena Fürst (1652-1717). As templates for this lesson, Merian made copperplate engravings, which became the basis of her first book publication. The New Flower Book was intended as a sample book for women embroidering. The first part contained a few copies of foreign flower pictures and appeared in 1675. The second and third parts, published in 1677 and 1680, contained our own studies of nature. The low editions and the useful nature of the work meant that today only a few of the pieces that were masterfully colored by Maria Sibylla Merian are still available.

A little later she published her caterpillar book in two parts (1679 and 1683): The caterpillars' wonderful transformation and strange flower food contained the results of their long-term observations. Here you can find the compositional principle that she also applied to her later work: on each leaf, the developmental stages of the insects are shown in connection with the plants that serve them as food. The prints were published in a relatively small octave format and on paper that was not first class, and only a few colored copies have survived - therefore the work did not achieve the same charisma as the Book of Insects from Surinam later.

For a long time the caterpillar book v. a. seen as a contribution to entomology. In fact, however, it should serve devotion, as the sentence in the foreword already shows: "So look here, not my glory, but only God's glory to praise Him as a creator of even these smallest and smallest worms." The book is right at this time The tradition of natural piety spread in Nuremberg, the search for God in the most insignificant creatures.

Netherlands

In 1685, after twenty years of marriage, Merian decided at the age of 38, together with her mother and two daughters (then 17 and 7 years old), to go to Walta State Castle near Wieuwerd in the Dutch Friesland for an indefinite period . Her stepbrother Caspar had been there since 1677 and had asked her to do so. The castle belonged to three sisters of the governor of Suriname, Cornelis van Aerssen van Sommelsdijk; they had made it available as a refuge for the early pietist sect of the Labadists . The approximately 350 people in the colony felt committed to early Christian ideals, beyond the natural orthodoxy of the official church. However, it was precisely this group, led by their preacher Yvon (1646–1707), that had developed into a strict, morally narrow-minded community that was prone to rapturous exaggeration, which hardly corresponded to Merian's nature.

It then assumed a certain special position in the colony. She provided her daughters with extensive artistic training, improved her own knowledge of Latin , gradually began again to paint butterflies and flowers and studied the collection of exotic butterflies from Suriname, which she found at Walta State Castle.

During this time she began to create her "study book". In it she collected small watercolors on parchment and noted observations of the caterpillars and butterflies depicted from earlier years. She presented new observations in Friesland in the same way and numbered them.

Johann Andreas Graff visited her in 1690 and reported on his experiences in a letter to Johann Jakob Schütz . He was particularly concerned about the well-being of his daughters (among other things because he had observed children being beaten) and complained that his wife was neglecting her artistic work. The marriage was divorced by a resolution of the city council of Nuremberg on August 12, 1692; Graff had filed for divorce so that he could remarry.

After the death of her mother - her stepbrother had died in 1686 - she left the Labadist group and settled in Amsterdam with her daughters in 1691 . Mostly the view is that she had chosen the multi-year stay at Waltha Castle as a deliberate turning point in order to gain distance from the efforts of the Nuremberg years and the failure of their marriage.

In Amsterdam she found numerous ideas for her artistic endeavors. As a recognized natural scientist, she was given access to the natural history cabinets , greenhouses and orangeries in the homes of wealthy citizens such as the collector of tropical plants Agnes Block . The acquaintance with Caspar Commelin, the director of the Botanical Garden in Amsterdam, proved to be particularly valuable for her studies; later he provided the scientific notes for her great book on insects from Suriname. She read intensively the newly published books on her specialty, entomology, and compared them with the results of her own studies. In addition, she painted depictions of flowers and birds for wealthy nature lovers, and she supplemented existing plant images with images of flies, beetles and butterflies; her daughters supported her. She used the contacts to influential citizens of the city to prepare the planned trip to Suriname.

Trip to Suriname

In February 1699 she sold a large part of her collections and her paintings to finance the trip. In April she deposited a will with an Amsterdam notary , in which she designated her daughters as universal heirs. In June 1699 she went with her younger daughter Dorothea Maria on board a merchant cruiser that took them to Surinam . She wrote about her intention in the foreword to Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium :

“In Holland , however, I was amazed to see what beautiful animals were allowed to come from East and West India ... In those collections I found these and countless other insects, but in such a way that their origin and reproduction were missing there means how they transform from caterpillars into pupae and so on. All of this stimulated me to take a long and expensive trip and to go to Suriname (a hot and humid country ...) to continue my observations there. "

Although friends and acquaintances urgently advised her not to travel to Suriname because of the extreme climate there, Maria Sibylla Merian did not allow herself to be dissuaded from her plans. She received financial support for her company from the city of Amsterdam. Initially from the state capital Paramaribo , later from the Labadist community Providentia, 65 km away , where they lived with the Pietist community, the two women undertook their excursions into the inaccessible primeval forests . There they observed, drew or collected everything they could discover about the tropical insects. Their classification of butterflies in daytime and moths (referred to by them as chapels and owls) is valid until today. They took plant names from the language used by the Indians . After a two-year stay, Merian, now 54, was no longer able to cope with the exertion and fell seriously ill with malaria . On September 23, 1701, she and her daughter returned to Amsterdam.

Amsterdam

The mayor made the town house available for an exhibition in which the exotic animal and plant preparations that had been brought with them could be seen and admired with great interest. Her drawings and collectibles served Merian as templates for parchment paintings, after which 60 copper engravings were made for a large-format masterpiece about the flora and fauna of Surinam, especially about the insects living there. Several engravers worked on it for three years. In 1705 the main work of Maria Sibylla Merian appeared in a leather, gold-decorated cover : Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In the introduction she stated:

“I was not addicted to profit in the production of this work, but wanted to be content with it when I get my expenses back. I spared no expense in carrying out this work. I have had the plates engraved by the most famous masters and have used the best paper for them, so that I can bring pleasure and pleasure to both art lovers and insect lovers, just as I will be delighted when I hear that I mean I achieved my intention and at the same time brought joy. "

Maria Sibylla Merian was now recognized as a great natural scientist and artist, but could not live on the income from her relatively expensive books alone. In addition, she gave painting lessons, traded, as in Nuremberg, in painting utensils and sold animal and plant preparations from her natural objects collection.

She suffered a stroke two years before her death and was only able to move around in a wheelchair afterwards. She died in Amsterdam in 1717 at the age of 69. In the death register she was referred to as "poor". The assumption that she was buried in a poor grave has now been disproved. On the day of her death, Robert von Areskin, personal physician of Peter the Great , bought a series of watercolors and the study book for herself that she had put on at Waltha Castle. Today everything is owned by the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg.

Inheritance and descendants

The younger daughter Dorothea Maria published the third volume of the caterpillar book in Amsterdam in 1717. In autumn she went to St. Petersburg with her second husband, the painter Georg Gsell (she was his third wife). Before that, she sold her mother's scientific and artistic estate to an Amsterdam publisher. Dorothea Maria worked as a teacher at the Academy of Arts and painted motifs similar to her mother. In 1736 she traveled to Amsterdam on behalf of Peter the Great to acquire more watercolors for him. She and her husband had a "blended family" with children from previous marriages of both partners and their own children; their descendants can be traced back to Russia for several generations.

The older daughter Johanna Helena married the Dutch overseas merchant Hendrik Herolt and lived with him in Suriname; their descendants can still be proven over several generations.

Lifetime achievement

Maria Sibylla Merian was one of the first researchers to systematically observe insects and find out something about their actual living conditions. She was able to show that each butterfly species as a caterpillar is dependent on a few forage plants and only lays its eggs on these plants. In particular, the metamorphosis of the animals was largely unknown. Although some scholars knew of the transformation of caterpillars into full-grown butterflies , wider circles of the population, but also many more educated people, the process was alien. Merian made a decisive contribution to changing this, not least because her book The Caterpillars Wonderful Metamorphosis and Strange Flower Food was published in German. For the same reason, however, many scholars of that time refused to recognize it - the specialist language of the scholars was Latin .

It was also unusual that she continued her work in South America . Trips to the colonies were common in order to settle there and get rich as quickly as possible by exploiting slaves or to search for treasures as adventurers. Research trips were practically unknown. Maria Sibylla Merian's travel plans were hardly taken seriously before she succeeded, under comparatively difficult circumstances, in discovering a number of previously unknown animals and plants in the primeval forests of Suriname, studying and documenting their development and later making her research results known in Europe close.

Regardless of the scientific results, it was above all the external circumstances of the trip that caused a stir. A woman around 1700, without male protection, accompanied by her daughter alone, was on the move for weeks on a merchant ship, in order to pursue her scientific work during the day for two years in the company of some Indians in a hot and humid climate in primeval forests near the equator - this achievement alone provided her Europe sustained fame and respect. Numerous biographies and a dozen novels about Maria Sibylla Merian appeared - while her scientific knowledge, although much noticed and historically significant at the time, was soon overtaken by the development of the natural sciences.

Carl von Linné referred to her work and named a moth after her. The plant genus Meriana Trew from the Iris family (Iridaceae) is named after her.

Her artistic work was already well received by her contemporaries. During a long interim period, the few volumes in the first edition quickly disappeared in university libraries and with some scholars and collectors. Several publishers tried to use Maria Sibylla Merian's popularity commercially by reprints of the Metamorphosis , but these editions never again reached the high level of the books she published. It was not until the 20th century that widespread interest in her drawn and colored leaves developed again. In the meantime it had become possible to reproduce the first edition true to the original with the help of highly developed reproduction and printing processes and to distribute it in larger editions.

The most important part of her butterfly collection ended up in the private collection of the banker Johann Christian Gerning (1745–1802) and his son Johann Isaak von Gerning (1767–1837) in Frankfurt am Main, with whom the Natural History Museum Wiesbaden was later founded. The still handsome specimens from Merian's collection can still serve as reference material for the museum's scientists today .

Appreciation in recent times

Exhibitions (selection)

- 2017: Cabinet exhibition Maria Sibylla Merian in the Museum Wiesbaden , from January 13th to July 9th 2017.

- 2017: Maria Sibylla Merian and the tradition of flower pictures in the Kupferstichkabinett Berlin , from April 7, 2017 to July 2, 2017

- 2017/2018: MARIA SIBYLLA MERIAN and the tradition of flower painting in the Städel , from October 11, 2017 to January 14, 2018.

Banknote and postage stamp

Towards the end of the 20th century, Maria Sibylla Merian's work was also publicly re-evaluated and recognized. Her portrait was originally intended for the 100 DM notes introduced in 1990 . For the portrait of Maria Sibylla Merian, however, only an artistically inferior etching by Johann Rudolf Schellenberg was available, as doubts about the authenticity of the original template arose. That is why the Bundesbank organized a design competition to get a high-quality master copy from this etching that would later become the basis for the portrait on the banknote. Since the 100 DM note was to be one of the first to appear, people were swapped due to these difficulties and the 500 DM note was given Merian's portrait. The reverse bore a picture of Merian with a dandelion, on which the caterpillar and butterfly of the gorse extensor are sitting. This design was retained until the changeover to euro banknotes .

Merian was also featured on a 40-pfennig postage stamp in 1987 .

Namesake

Numerous schools are named after her, including a comprehensive school in Bochum-Wattenscheid . In Dresden and Frankfurt the Merianplatz was named after her.

A German research ship for investigations in the area of the ice edge, based at the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde, has been named Maria S. Merian since July 26, 2005 . The ship was handed over to the institute on February 9, 2006 off Warnemünde and put into service. A passenger ship on the Frankfurt Primus Line bears the name Maria Sibylla Merian .

A crater 22 km in diameter was named after her on Venus.

The Academic Women's Association Meriana, founded in 2007 in Frankfurt am Main , chose its name as an expression of respect for Merian.

In June 2017 the building of the Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Center in Frankfurt am Main was renamed Maria Sibylla Merian-Haus .

In 2018, Maria-Merian-Gasse in Vienna- Donaustadt (22nd district, Seestadt Aspern ) was named after her.

Maria Sibylla Merian Prize

Every year between 1994 and 2009, the Hessian Ministry of Science and Art awarded two young artists the Maria Sibylla Merian Prize . This should give special support to female artists, as they are still disadvantaged. It was repeatedly suggested that the prize should be divided in such a way that half each went to a young artist and half to a young scientist .

The Maria Sibylla Merian Society

The Maria Sibylla Merian Society was founded in May 2014 in Amsterdam. It is an interdisciplinary association that is open to anyone interested and is dedicated to further research into Merian's life and work. A symposium was held on the 300th anniversary of her death in 2017. The Society's website includes a. Essays and scientific literature (including from the two symposia in 2014 and 2015) as well as pictures, documents and letters from MS Merian.

Others

Numerous motifs from Meissen porcelain are inspired by her illustrations.

Works

Publications

-

New flower book . Reprint 1999, 2003 in 2 volumes: Prestel, Munich, ISBN 3-7913-2060-2 , ISBN 3-7913-2663-5

- Volume 1. Nuremberg 1675.

- Volume 2. Nuremberg 1677.

- Volume 3. Nuremberg 1680.

- The caterpillars' wonderful transformation and strange flower food . 3 volumes (Microform 1991). Harenberg, Dortmund 1982 (reprint), ISBN 3-88379-331-0

-

The caterpillars are wonderfully transformed and have a strange food for flowers. First and other part. Reprint, Berlin 2020, ISBN 978-3-96849-008-3 .

- Volume 1: Graff, Nuremberg 1679. Digitized version of the University Library Erlangen-Nuremberg

- Volume 2: Graff, Frankfurt 1683. Digitized version of the Heidelberg University Library

- Volume 3: Merian, Amsterdam 1717. Google Books . Edition Amsterdam 1730: De europische Insecten digitized of the University of Göttingen

-

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium , Amsterdam 1705. Digitized version of the University of Göttingen in Dutch

- Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium ( Dissertatio de generatione et metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium ) 1719 (with supplemented plates, a total of 71 plates)

- Reprint 1980-1982: Piron, London

- Reprint 1992: Insel, Frankfurt am Main, ISBN 3-458-16171-6

First editions in libraries (selection)

The Saxon State Library in Dresden owns one of the six copies of the Flower Book (1680) that have survived worldwide .

First editions of the Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (1705) can be found in the following museums:

- Royal Library in The Hague

- Austrian National Library in Vienna

- University Library Basel doi : 10.3931 / e-rara-5285

- University library in Jena

- Kupferstichkabinett in Basel

- City and University Library in Frankfurt am Main

- Saxon State Library in Dresden

- Library of the Germanic National Museum , there are also four pictures of Merian

gallery

literature

- Barbara Beuys : Maria Sibylla Merian. Artist, researcher, businesswoman . Insel Verlag, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-458-31680-0 . Meeting .

- Margarete Pfister-Burkhalter: Iconographic overview of the portraits of Maria Sybilla Merian (1647-1717). In: Bulletin of the Swiss Bibliophile Society , Vol. 6, 1949, pp. 31–42 ( digitized version ).

- Neues Blumenbuch (Insel-Bücherei No. 2004), reprint of the original edition with an afterword, by Helmut Decker, 3rd edition, 2013, ISBN 978-3-458-20004-8 .

- Boris Friedewald : Maria Sibylla Merian's Journey to the Butterflies. Prestel Verlag, Munich, London, New York 2015, ISBN 978-3-7913-8148-0 .

- Christina Haberlik, Ira Diana Mazzoni : 50 classics - artists, painters, sculptors and photographers . Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 2002, ISBN 978-3-8067-2532-2 , pp. 36-39.

- Helmut Kaiser : Maria Sibylla Merian: A biography . Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 2001, ISBN 3-538-07051-2 .

- Charlotte Kerner : silkworm, jungle blossom. The life story of Maria Sibylla Merian. Beltz & Gelberg, Weinheim 1998, ISBN 3-407-78778-2 .

- Diana Krause: Maria Sibylla Merian - adored, scorned, forgotten? Reception history of an “incomprehensible”. In: Constanze Carcenac-Lecomte et al. (Ed.): Steinbruch. German places of remembrance. Approaching a German history of memory. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 3-631-36272-2 , pp. 29-47.

- Dieter Kühn : Ms. Merian! A life story. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-10-041507-8 .

- The little book of tropical wonders. Colored engravings by Maria Sibylla Merian. 6th edition. Insel, Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig 1999, Insel-Bücherei 351 / 2B, ISBN 3-458-8351-0 .

- Heidrun Ludwig: Nuremberg natural history painting in the 17th and 18th centuries. Basilisken-Presse, Marburg an der Lahn 1998 (Acta biohistorica; 2). Zugl .: Berlin, Techn. Univ., Diss., 1993, ISBN 3-925347-46-1 .

- Gertrud Lendorff : Maria Sibylla Merian, 1647–1717. Your life and work. Basel 1955.

- Debra N. Mancoff: Women Who Changed Art. Prestel Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-7913-4732-5 , pp. 10, 41, 44-45.

- Erich Mulzer : Maria Sibylla Merian and the house Bergstrasse 10. In: Nürnberger Altstadt reports. Edited by Altstadtfreunde Nürnberg e. V. Nürnberg 1999, pp. 27-56.

- Maria Sibylla Merian and the tradition of the flower picture. Edited by Michael Roth, Martin Sonnabend, exhibition catalog, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-7774-2787-4 .

- Kathrin Schubert: Maria Sibylla Merian. Trip to Suriname. Frederking & Thaler, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-89405-772-5 .

- Ruth Schwarz, Fritz F. Steininger: Maria Sibylla Merian. Life pictures. Schwarz, Frankfurt am Main 2006.

- Katharina Schmidt-Loske: The animal world of Maria Sibylla Merian. Marburg / Lahn 2007, ISBN 978-3-925347-79-5 .

- Anne-Charlotte Trepp: Insect metamorphosis as a passion or Maria Sibylla Merian's long path to rebirth. In: To know everything about the bliss. The exploration of nature as a religious practice in the early modern period (1550–1750). Campus-Verlag: Frankfurt a. M. and Munich 2009, p. 210 ff.

- Christiane Weidemann, Petra Larass, Melanie Klier: 50 women artists you should know. Prestel, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-7913-3957-3 , pp. 34-35.

- Kurt Wettengl (Ed.): Maria Sibylla Merian. Artist and natural scientist 1647–1717. Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern 2004, ISBN 978-3-7757-1226-2 .

- Kurt Wettengl: From natural history to natural science. Maria Sibylla Merian and the Frankfurt Natural History Cabinets of the 18th Century. Kleine Senckenberg series, volume 46.Swisserbeard, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-510-61360-0 .

- Maria Sibylla Merian of Basel, 1647–1717. In: Rudolf Wolf : Biographies on the cultural history of Switzerland. Volume 3, Orell Füssli, Zurich 1860, pp. 113–118.

- Lucas Wüthrich: Merian, Maria Sibylla. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 17, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-428-00198-2 , p. 138 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Natalie Zemon Davis : Metamorphoses. The life of Maria Sibylla Merian. Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-8031-2484-0 .

Fiction

- Inez van Dullemen: The flower queen. A Maria Sibylla Merian novel . Structure, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-7466-1913-0 .

- Utta Keppler: The butterfly woman: Maria Sibylla Merian. Biographical novel . Salzer, Bietigheim-Bissingen 1977; dtv, Munich 1999, 2000, ISBN 3-423-20256-4 .

- Olga Pöhlmann : Maria Sibylla Merian. Novel. Krüger, Berlin 1935.

- Werner Quednau : Maria Sibylla Merian. The life path of a great artist and researcher. Novel . Mohn Verlag, Gütersloh 1961.

Web links

- Literature by and about Maria Sibylla Merian in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Maria Sibylla Merian in the German Digital Library

- Search for Maria Sibylla Merian in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Maria Sibylla Merian on the website of the RKD Netherlands Institute for Art at rkd.nl (English, accessed on August 26, 2016)

- Publications by and about Maria Sibylla Merian in VD 17 .

- The Maria Sibylla Merian Society

- Lucas Wüthrich: Merian, Maria Sibylla. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Marguerite Menz-Vonder Mühll: Merian, Maria Sibylla. In: Sikart

- Stefan Schmitt: Power of Nature - Maria Sibylla Merian. In: Die Zeit , November 12, 2009

- Birgit Schmidt: Maria Sibylla Merian. Artist and naturalist, painter of flowers and insects , about the exhibitions in Wiesbaden, Berlin and Frankfurt (2017/2018)

- Merian, Maria Sibylla. Hessian biography. (As of January 13, 2017). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- Renate Ell: Maria Sibylla Merian - natural scientist and artist Bavaria 2 radio knowledge . Broadcast on January 2, 2017 (podcast)

- Jutta Duhm-Heitzmann: 01/13/1717 - Anniversary of the death of Maria Sibylla Merian WDR ZeitZeichen on January 13, 2017 (podcast)

biography

- Biography of Maria Sibylla Merian at the Deutsches Museum

- Maria Sibylla Merian. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

- About Maria Sibylla Merian . Botanical Art & Artists . English. Biography, references, links, illustrations

- Merian, Maria Sibylla in the Frankfurt personal dictionary

Digital copies

- View original editions Digitization project of the Georg-August-Universität Göttingen

- Digitized books by Maria Sibylla Merian from the holdings of the Bamberg State Library (search term: Merian)

- MS Gräffin, M. Merians des Eltern seel: Daughter. New book of flowers at the Saxon State Library - State and University Library Dresden

Individual evidence

- ↑ Family tree of Maria Sibylla Merian

- ↑ In this article the historically common spelling Suriname is used for the country Suriname .

- ↑ insectum. In: Johann Heinrich Zedler : Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 14, Leipzig 1735, column 741.

- ↑ Erich Mulzer: Maria Sibylla Merian and the house Bergstrasse 10. In: Nürnberger Altstadt reports. Ed. Altstadtfreunde Nürnberg e. V., Nürnberg 1999, pp. 27-56.

- ↑ a b Erich Mulzer: Maria Sibylla Merian and the house Bergstrasse 10. In: Nürnberger Altstadt reports. Ed. Altstadtfreunde Nürnberg e. V., Nürnberg 1999, p. 48.

- ^ A b Anne-Charlotte Trepp: Insect metamorphosis as a passion or Maria Sibylla Merian's long path to rebirth. In: To know everything about the bliss. The exploration of nature as a religious practice in the early modern period (1550–1750). Campus-Verlag: Frankfurt a. M. and Munich 2009, p. 210 ff.

- ↑ Davis, Natalie Zemon: Metamorphoses - The life of Maria Sibylla Merian . 1st edition. Wagenbach, Berlin 2003, p. 51/52 .

- ^ Renate Ell: Maria Sibylla Merian - natural scientist and artist. ( Memento of the original from November 17, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ; Radio feature, Bayern 2 , April 29, 2013 (accessed November 15, 2015)

- ^ Davis, Natalie Zemon: “Metamorphoses - The Life of Maria Sibylla Merian”, p. 16 and p. 135, footnote 3

- ^ Illustration of a lapwing from the holdings of the Fogg Art Museum , harvardartmuseums.org, accessed on April 2, 2013

- ↑ Barbara Beuys: On the 300th anniversary of the death of Maria Sibylla Merian. Retrieved July 22, 2018 .

- ^ Elisabeth Rücker: Entrepreneur and publisher . in: Maria Sibylla Merian, artist and naturalist, 1647-1717. Ed .: Kurt Wettengl. Hatje Cantz, Frankfurt / Main 1997, p. 261 .

- ↑ Natalie Zemon Davis: Metamorphoses - The life of Maria Sibylla Merian . Wagenbach, Berlin 2003, p. 153 .

- ↑ Natalie Zemon Davis: Metamorphoses - The life of Maria Sibylla Merian . Wagenbach, Berlin 2003, p. 111, 130 .

- ^ Renate Ell: descendants of Dorothea Maria Graff and Georg Gsell. Retrieved November 19, 2017 .

- ↑ Renate Ell: Descendants of Johanna Helena Graff and Hendrik Herolt. Retrieved November 19, 2017 .

- ↑ Lotte Burkhardt: Directory of eponymous plant names - Extended Edition. Part I and II. Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin , Freie Universität Berlin , Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-946292-26-5 doi: 10.3372 / epolist2018 .

- ↑ Museum Wiesbaden ( Memento of the original from January 31, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Between art and science. In: FAZ of January 12, 2017, page 31.

- ↑ Städel

- ^ Artistic nature in FAZ of October 10, 2017, page 34

- ↑ Deutsche Bundesbank (ed.): From cotton to banknotes . A new series of banknotes is created. 2nd Edition. Verlag Fritz Knapp GmbH, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-611-00222-4 , p. 15-16 .

- ^ Merian , Venus Crater Database, Universities Space Research Association.

- ↑ ADV Meriana Frankfurt: Name. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ↑ New names for Senckenberg buildings - Videos - rheinmaintv. (Video, 30 seconds) (No longer available online.) In: rheinmaintv.de. Archived from the original on July 17, 2017 ; accessed on June 10, 2017 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Compilation of motifs on the Porzellanmanufaktur website ( Memento of the original from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed April 2, 2013

- ↑ Description on the publisher's website

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Merian, Maria Sibylla |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Merian, Mariam Sibillam; Merian, Maria Sibilla; Merian, Maria Sybilla |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Naturalist and artist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 2, 1647 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Frankfurt am Main |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 13, 1717 |

| Place of death | Amsterdam |