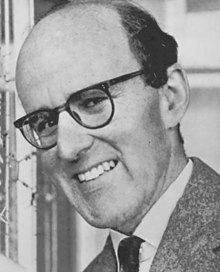

Max Ferdinand Perutz

Max Ferdinand Perutz (born May 19, 1914 in Vienna , Austria-Hungary , † February 6, 2002 in Cambridge ) was an Austro- British chemist . He received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1962.

Life

Max Perutz's parents were Adele ("Dely", née Goldschmidt) and Hugo Perutz. Both parents came from wealthy textile manufacturer families from assimilated Judaism, but the son was brought up in the Roman Catholic denomination. After visiting the Theresianum in Vienna, he began studying at the University of Vienna in 1932 . There, his interest in biochemistry was primarily aroused by courses with Friedrich Wessely . After he had completed his first university degree in Vienna in 1936, he went to England and joined the Cavendish Laboratory of the University of Cambridge as a research assistant in a crystallography research group under John Desmond Bernal . Under the supervision of William Lawrence Braggs , he completed his Ph.D. In Cambridge he also began researching hemoglobin , which is responsible for the transport of oxygen in the blood and which would occupy him for most of his research career .

In 1947 he founded a professor in Cambridge , the Department of Molecular Biology (Laboratory of Molecular Biology), which he headed until 1979th There worked Francis Crick , Hugh Huxley , James Watson , Sydney Brenner , Fred Sanger and Aaron Klug . With Perutz as director, the institute became the birthplace of molecular biology, from which fifteen Nobel Prize winners emerged. At Cambridge he also became a member of the Peterhouse , where he was made an Honorary Fellow in 1962 . He took great care of the new members and was also a regular and popular speaker for the Kelvin Club , the college's scientific society.

After Nazi Germany annexed Austria in 1938, Perutz was expelled from the country because of its Jewish origins. When the Second World War broke out, Perutz was deported from England to Canada along with other persons of German or Austrian descent , as a contribution of the country to bear the burden of war in the Commonwealth. When the camp conditions in Canada improved, at first fascist prisoners of war and refugees were housed together, then they were separated after loud protests, Perutz acted as a camp teacher for the refugees, like many other inmates with an intellectual or manual background.

During the war he worked on the Habbakuk project . The aim of this research project was to build an aircraft platform in the middle of the Atlantic where aircraft could be supplied and refueled. To do this, he investigated the recently discovered substance pykrete , a mixture of ice and wood fibers. To this end, he also carried out early-stage experiments with Pykrete under the Smithfield Meat Market in London . Perutz had been selected for this research project because he had researched the changes in crystal arrangements in the layers of glacial ice before the war . After the war, he briefly returned to glaciology and demonstrated, among other things, how glaciers flow.

In 1953 Perutz showed that one could use the diffraction of X-rays on protein crystals , which were alternately mixed with heavy atoms or not mixed with them, in order to clarify the structure of the crystals (solution of the phase problem). In 1958, John Kendrew and others succeeded in elucidating the first protein structure, that of myoglobin . In 1959 Max Perutz used this technique to elucidate the structure of the protein hemoglobin. For this work he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1962 together with John Kendrew. Today several thousand molecular structures of proteins are determined by X-ray crystallography.

After 1959, Perutz and his colleagues continued to determine the structure of oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin at high resolution. As a result, in the 1970s, he was finally able to explain the exact function of hemoglobin: how it switches back and forth between the oxidized and the non-oxidized form and regulates the uptake of oxygen and its release in muscles and organs. Further work over the next two decades refined and reinforced Perutz's research results on the functioning of hemoglobin. In addition, Perutz also studied the structural changes in hemoglobin in many hemoglobin diseases and how this impaired oxygen binding. He hoped to be able to use this molecule as a drug receptor in order to slow down or even cure the consequences of sickle cell anemia . Another of his research areas was the diversity of the hemoglobin structures of different species in order to adapt to different habitats and behavior patterns. In the last years of his life, Perutz worked on changing protein structures, such as those caused by Huntington's disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. In this case, it showed that the Huntington's disease the number of glutamine related repeats, as this combines to form shapes that it comprises opposite zipper called (engl. Polar zipper).

Perutz died in 2002 of Merkel cell carcinoma , a rare skin cancer. Until recently, he worked on a scientific project that he had started a few years earlier and that dealt with an atomic model of amyloid fibers. The preliminary final result of his investigations was published posthumously in April 2002.

In Vienna, on the Vienna Biocenter campus, both the subject-specific library and the Max F. Perutz Laboratories , a joint venture between the University of Vienna and the Medical University of Vienna, bear his name. The same applies to the Perutz Glacier in Antarctica.

The author

In his later years, Perutz was a regular reviewer / essayist for The New York Review of Books on biochemical topics. Many of these essays were summarized in 1998 in his book I wish I had made you angry earlier . Perutz's literary ambitions had been criticized in his childhood by his relative Leo Perutz , a well-known writer, who told the boy that he would never be a good writer. An unjustified statement, as one can determine from the remarkable letters that Perutz wrote as a minor. These letters are summarized in the book What a Time I Am Having: Selected Letters of Max Perutz . Max Perutz was also delighted that he received the Lewis Thomas Prize in 1997 for his scientific writings .

Others

At a lecture on Living Molecules in Cambridge in 1994, Perutz also attacked the theories of the philosophers Karl Popper and Thomas S. Kuhn and the biologist Richard Dawkins . He criticized Popper's view that scientific progress occurs through a sequence of hypothesis creation and refutation, stating that hypotheses do not necessarily have to be the basis of scientific research and, at least in molecular biology, they do not necessarily have to be subject to change. Kuhn's view that scientific progress takes place in paradigm shifts triggered by social and cultural pressure was, for Perutz, an unfair representation of modern science.

He expanded his criticism to include scholars who criticized religions, especially Richard Dawkins. Statements that violated religious beliefs were tactless for Perutz and simply damaged the reputation of science. He concluded, "Even if we don't believe in God, we should try to live as if we did."

In the days following the September 11, 2001 attacks , Perutz wrote to British Prime Minister Tony Blair , appealing not to use military means to respond: “I am alarmed by American calls for retaliation and I am concerned that President Bush's revenge is killing thousands of innocent people and plunge us into a world of escalating terror and counter-terror. I hope you can use your moderating influence to keep this from happening. "

Private

Max Perutz married Gisela Peiser in 1942. This marriage had two children: Vivien (* 1944), an art historian, and Robin (* 1949), a professor of chemistry at the University of York.

Awards

- 1954: Member of the Royal Society

- 1962: Nobel Prize in Chemistry , together with John Cowdery Kendrew

- 1963: Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- 1963: Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- 1964: Member of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina

- 1965: Honorary doctorate from the University of Vienna

- 1967: Austrian Decoration of Honor for Science and Art

- 1967: Wilhelm Exner Medal

- 1968: Member of the American Philosophical Society

- 1970: Member of the National Academy of Sciences

- 1971: Royal Medal of the Royal Society

- 1972: Honorary doctorate from the University of Salzburg

- 1975: Order of the Companions of Honor

- 1976: Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- 1976: External member of the Académie des Sciences

- 1979: Copley Medal

- 1983: Corresponding member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences

- 1985: External member of the Academy of Sciences of the GDR

- 1987: together with John Meurig Thomas Christmas Lectures (Crystals and Lasers).

- 1989: Order of Merit

- 1993: Otto Warburg Medal

- 1997: Lewis Thomas Prize

Main work

- Proteins and nucleic acids . 1962

Web links

- Literature by and about Max Ferdinand Perutz in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Max Ferdinand Perutz in the German Digital Library

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the 1962 award to Max F. Perutz (English)

- Entry on Perutz, Max Ferdinand (1914-2002) in the Archives of the Royal Society , London

- Entry about Max Ferdinand Perutz in the database of the Wilhelm Exner Medal Foundation .

- Max Perutz Library

- Max F. Perutz Laboratories

- Recordings for and with Max Perutz in the online archive of the Austrian Media Library

- Wolfgang Burgmer: May 19, 1914 - birthday of the biochemist Max Perutz WDR ZeitZeichen on May 19, 2019 (podcast)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Max F. Perutz - Facts. Nobeprize.org - The official website of the Nobel Prize, accessed July 25, 2013 .

- ^ LMB Nobel Facts - MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology . In: MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology . ( cam.ac.uk [accessed November 3, 2017]).

- ↑ Annette Puckhaber: A privilege for the few. German-speaking migration to Canada in the shadow of National Socialism. Lit, Münster 2000. Zugl. Diss. Phil. University of Trier , p. 223 full text

- ↑ Albert Gossauer: Structure and reactivity of biomolecules. Verlag Helvetica Chimica Acta, Zurich 2006, ISBN 3-906390-29-2 , p. 449.

- ↑ Max Perutz May 19, 1914 to February 6, 2002. (PDF file; 99 kB) Obituary - excerpt from the yearbook of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences, 2002, p. 331f.

- ^ Max Perutz Library

- ^ Member entry of Max Ferdinand Perutz at the German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina , accessed on October 12, 2012.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Perutz, Max Ferdinand |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Perutz, Max |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British chemist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 19, 1914 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vienna , Austria-Hungary |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 6, 2002 |

| Place of death | Cambridge |