Attacks on North America during World War II

| date | February 23, 1942 to April 1945 |

|---|---|

| place | North America , Atlantic Ocean , Pacific Ocean |

| output | Allied victory, defense of North America |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

1941

Thailand - Malay Peninsula - Pearl Harbor - Hong Kong - Philippines - Guam - Wake - Force Z - Borneo

1942

Burma - Rabaul - Singapore - Sumatra - Timor - Australia - Java - Salamaua - Lae - Indian Ocean - Port Moresby - Coral Sea - Midway - North America - Buna-Gona - Kokoda-Track

The attacks on North America during the Second World War on the part of the Axis powers were relatively rare, mainly because of its distance from the central theaters of war in Europe and Asia. They include attacks on continental territory (up to 370 km from the coast) of the United States , Canada, and Mexico . This also includes several smaller states, but not the Danish territory of Greenland , the Hawaiian island chain and the Alëuts .

Japanese operations

Japanese submarine operations

Marine traffic has been attacked several times off the west coast of the United States within sight of cities such as Los Angeles and Santa Monica . Between 1941 and 1942, more than ten Japanese submarines operated off the west coast. These attacked American, Canadian and Mexican ships and sank ten of them.

Attack on Ellwood

The first shelling of the American mainland by the Axis powers occurred on February 23, 1942, when the Japanese submarine I-17 attacked the Ellwood oil field, west of Goleta , near Santa Barbara , California . Even if only a pump house and a jetty near an oil well were damaged, frigate captain Nishino Kōzō ( 西 野 耕 三 ) reported to Tokyo that he had set all of Santa Barbara on fire. The attack left no casualties and the damage ranged from $ 500 to $ 1,000. Most of all, what followed was fear of an invasion of the west coast.

Attack on the Estevan Point lighthouse

On June 20, 1942, the Japanese submarine I-26 under the command of Frigate Captain Yokota Minoru ( 横 田 稔 ) fired 25 to 30 140 mm projectiles at the lighthouse Estevan Point ( Vancouver Island , British Columbia ), but missed it . This was the first attack on Canadian soil since the British-American War of 1812. Although no people were harmed, the subsequent darkening of the outer stations had a disastrous effect on shipping.

Attack on Fort Stevens

On June 21 and 22, 1942, the Japanese submarine I-25 under the command of frigate captain Tagami Meiji ( 田 上 明治 ) fired several projectiles at the Fort Stevens military base . The shelling from the mouth of the Columbia River , Oregon , was the only attack on a military facility on the American mainland. The only documented damage was on a baseball field . However, some large telephone cables were still damaged. The riflemen at Fort Stevens were banned from returning fire during the incident as the Japanese would have had a better target that way. The Japanese submarine was ultimately found by an American training aircraft. Despite a subsequent bomber attack, I-25 managed to escape.

Fort Stevens was a US Army coastal fortification in the US state of Oregon. The fort formed the main fortification of the coastal fortification of the mouth of the Columbia River comprising three forts. The other two forts were Fort Canby and Fort Columbia in Washington State. Fort Stevens was built during the American Civil War and served military purposes until 1952.

Lookout air strikes

The first air strike by an enemy force on the American mainland took place on September 9, 1942 on Mount Emily ( Brookings (Oregon) ), in the form of the so-called Lookout air strikes. It was an attempt by a Japanese seaplane , model Yokosuka E14Y , to cause a forest fire with incendiary weapons . The aircraft, which was piloted by Fujita Nobuo ( 藤田 信 雄 ), had been launched from the Japanese submarine I-25 . No major damage was caused, including another attack on September 29th. The September 9, 1942 release was listed as a memorial on the National Register of Historic Places in 2006 and is called the Wheeler Ridge Japanese Bombing Site .

Balloon bomb attacks

Between November 1944 and April 1945 the Japanese Navy launched over 9,000 balloon bombs towards the United States. Driven by the jet stream, which was only discovered at the time , they sailed across the Pacific Ocean to North America, where they were supposed to start forest fires and cause other damage. According to reports, about 300 of the balloon bombs arrived in North America without causing any serious damage. A total of six people (five children and one woman) were killed in the attacks on mainland North America during World War II when one of the children stepped on and exploded a bomb near Bly , Oregon . The site is now marked by a stone monument in the Mitchell Recreation Area in the Fremont Winema National Forest. Reports from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the Canadian military indicate that the balloon bombs reached Saskatchewan . It is also believed that such a bomb was the cause of the third fire in the Tillamook fires . A member of the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion died on August 6, 1945 while fighting a fire in the northwestern United States. Additional wounds to the 555th included two broken bones and 20 other injuries.

German operations

German landings in the United States

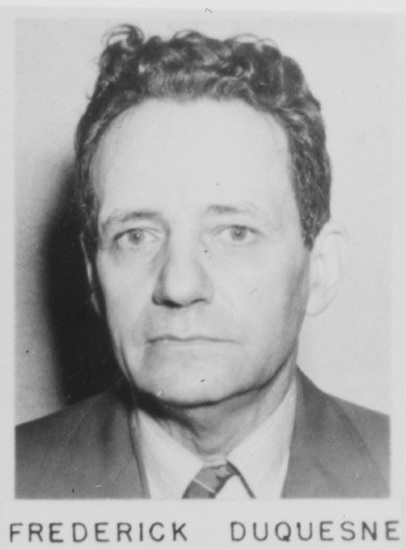

Duquesne spy ring

Even before the war, a large spy ring operating in the country was discovered in the United States . The Duquesne Spy Ring is still to this day the biggest year ended in convictions espionage case in the history of the United States. Employed in key jobs in the USA, the 33 German agents of the ring were supposed to obtain information that could be useful in the event of war, and also to carry out acts of sabotage . For example, a person opened a restaurant to get information about their customers; another worked for an airline reporting Allied ships crossing the Atlantic Ocean ; others in the ring worked as messengers so that they could deliver secret messages as well as normal messages.

The spy ring was headed by Fritz Joubert Duquesne , a South African Boer who worked as a spy for Germany in both world wars . Better known as " The Man Who Kitchener killed ," he got for his key role in sabotage and sinking of HMS Hampshire an Iron Cross awarded.

William G. Sebold , a double agent for the United States, played a major role in the FBI's investigation . Sebold ran a radio station for the Ring in New York for about two years, providing the FBI with valuable information about what Germany was sending to its spies in the United States. He also checked the information that the German spies sent to their homeland. On June 29, 1941, the FBI struck. All 33 spies were arrested, found guilty and sentenced to a total of over 300 years in prison.

Operation Pastorius

When the United States intervened in World War II, the remaining German saboteurs in the United States were ordered to wreak havoc. The orders for this were given by the intelligence service Abwehr . In June 1942 eight agents were recruited who were divided into two teams: the first team led by George John Dasch (alias George Davis) continued to consist of Ernst Peter Burger , Heinrich Heinck and Richard Quirin. The second team, in addition to their commanders Edward Kerling, Hermann Neubauer, Werner Thiel and Herbert Haupt.

On June 12, 1942, the German submarine U-202 dropped the Dasch team, armed with explosives and plans for East Hampton ( Long Island , New York ). Their plan included blowing up power plants at Niagara Falls and three Alcoa power plants in Illinois , Tennessee and New York . Dasch turned himself in to the FBI and gave him all the information about the planned mission, which led to the arrest of the entire team.

Kerling's group landed on June 17, 1942 with U-584 at Ponte Vedra Beach (40 km southeast of Jacksonville , Florida ). Their job was to mine four areas: the Pennsylvania Railroad in Newark , New Jersey , canal locks in St. Louis and Cincinnati , and other places in New York. Dasch's confession also led to the arrest of Kerling's group on July 10th.

All eight German agents were tried by a military tribunal , in which six of them were sentenced to death . President Roosevelt endorsed the decisions. The constitutionality of the tribunal has been approved by the Supreme Court in Ex parte Quirin worn and the six men were on August 8, 1942 executed . Dasch and Burger were both sentenced to 30 years in prison. In 1948 they were released and deported to Germany. Dasch, who had lived in America for a long time before the war, could not live an easy life in Germany because of his collaboration with the United States authorities. One condition of his deportation was that he was never allowed to return to the USA, which was not changed by the many letters he wrote to prominent Americans (for example to J. Edgar Hoover and President Eisenhower ). He later moved to Switzerland , where he wrote the book Eight Spies Against America .

Operation Magpie

Under the code name Operation Elster there was another attempt at infiltration by Germany against the USA in 1944. Part of this operation were Erich Gimpel and the German-American defector William Colepaugh . Their job was to gather information about the Manhattan Project and, if possible, sabotage it. The two started in Kiel with U-1230 , which brought them to Hancock Point in Maine on November 30, 1944 . They made it to New York and went undetected, but Colepaugh later deserted. After Gimpel was able to take the luggage and the suitcase with the spy contents from him, Colepaugh found himself in his hopeless situation with old acquaintances who informed the FBI on December 26th. Colepaugh revealed the entire plan, and Gimpel was arrested four days later. Before his arrest, Gimpel managed to send a message about the nuclear weapons in the USA to the defense service in Germany. Both received the death penalty, which was later commuted to life imprisonment. Gimpel then spent the next ten years in prison. Fired in 1960, Colepaugh started a business in King of Prussia , Pennsylvania before retiring in Florida .

German landings in Canada

St. Martins, New Brunswick

At about the same time as the Dasch operation (25 April 1944) landed the German defense agent Marius A. Langbein with a submarine near the Canadian St. Martins, New Brunswick . His job was to observe shipping traffic in Halifax, Nova Scotia , which was the main departure point for Atlantic convoys. However, Langbein decided against the project soon after and moved to Ottawa, where he lived on the funds made available to him. In December 1944, he surrendered to the Canadian authorities.

New Carlisle, Quebec

In November 1942, U-518 sank two freighters loaded with iron ore off Bell Island, Conception Bay ( Newfoundland ). Despite an attack by the Royal Canadian Air Force , the spy Werner von Janowski succeeded on November 9, 1942 in New Carlisle (Québec) . His disguise did not last long after Earl Annett Jr, manager of the New Carlisle Hotel, became suspicious of his guest when he was using outdated currency in the hotel bar. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police then arrested Janowski on board a Canadian National Railway train to Montreal . A search of his personal belongings found, among other things, a very powerful radio station . Later he worked as a double agent who sent false information to the Abwehr in Germany. The effectiveness and honesty of his "turn" is still discussed today.

Weather station Kurt, Martin Bay

Precise weather information was particularly important during the naval war. This is why U-537 set sail from Kiel on September 18, 1943 . The goal of the crew consisting of a meteorological team led by Professor Kurt Sommermeyer was Martin Bay, which they should reach via Bergen in Norway . On October 22nd, she arrived near the northernmost point of Labrador in Martin Bay, where she set up an automatic weather station ( weather station Kurt or weather radio Land-26 ). The station was powered by batteries that were believed to last about three months. In early July 1944, U-867 set out from Bergen to replace the station's equipment, but was sunk on the way there. The weather station remained undamaged until the 1980s; today it is in the Canadian War Museum .

German submarine operations

Canada

From the beginning of the war in 1939 until the end of the war in Europe, some ports on the Atlantic coast of Canada became important supply connections for the United Kingdom and later for the Allied land offensives on mainland Europe. Halifax and Sydney, Nova Scotia , were the ports of departure for convoys, with the fast convoys starting their crossing to Europe in Halifax and the slow convoys in Sydney. Both ports were heavily secured and equipped with coastal radar, floodlight batteries and coastal artillery. All of these military defenses were manned by regular and reserve personnel from the Royal Canadian Navy and Royal Canadian Army . Strict blackout measures were imposed and anti-submarine nets were installed in front of the port entrances. The port of Saint John was less important , where war material was loaded, especially after the American entry into the war in December 1941.

On February 23, 1940, the Commander-in-Chief of the German Navy, Erich Raeder , presented Adolf Hitler with “Considerations on the use of two submarines with mines and torpedoes against Halifax”, but the minutes noted: “Fuehrer refuses to use it because of psychological effects UNITED STATES".

In June 1941, the U 111, the first German submarine, appeared off Canada. It was commissioned to investigate the maritime traffic situation on Canada's Atlantic coast for later attacks on Canadian shipping. During the reconnaissance trip, the submarine was hindered by pack ice, icebergs and fog.

In the Canadian side of the Battle of the St. Lawrence River named German submarine offensive of 1942 in Canada's inland waters, shipping traffic in the St. Lawrence Gulf and St. Lawrence River was successfully attacked. However, the greatest ship losses occurred in the years 1941 to 1945 off the Canadian Atlantic coast. Not only are the direct losses from torpedoes, mines and artillery fire from submarines to be taken into account, but also the many war-related losses. These include, for example, the sinking of the ships in the collisions caused by the submarines being forced to travel in convoy in the Canadian Atlantic waters, which are badly affected by fog, ice and storms. Despite the loss of ships, the German submarine war did not have a paralyzing effect on the Canadian war effort, but on the other hand also hit the moral of the Canadian population.

As the last ship off the Canadian coast, the HMCS Esquimalt mine sweeper, which was hunting submarines, was sunk by U 190 on April 16, 1945 .

Newfoundland

There were three major attacks in 1942 when German submarines attacked four iron ore freighters traveling for a DOSCO mine in Wabana on Bell Island in Conception Bay , Newfoundland . The SS Saganaga and the SS Lord Strathcona were sunk by U-513 on September 5, 1942 , while the SS Rosecastle and PLM 27 were sunk by U 518 on November 2, 1942 . After these attacks, a torpedo was shot at the 3,000-tonne Collier Anna T , which missed its target, hit a DOSCO loading pier and exploded.

On October 14, 1942, the Caribou , a ferry of the Newfoundland Railway , was shot at by the German submarine U 69 and sank in Cabotstrasse , south of Port aux Basques . The Caribou had 45 crew members and 206 civil and military passengers on board. 137 died in the attack, many of them Newfoundland dogs.

United States

"Enterprise Bump" 1942

The Atlantic Ocean was a key strategic zone in both World War I and World War II . The east coast of the United States in particular offered easy targets for German submarines after Germany declared war on the United States . After a highly successful foray by five Class IX boats, the offensive of short-range submarine class VII boats was maximized. The ships equipped with larger fuel supplies were supplied by support submarines . From February to May 1942, 348 ships were sunk, with the loss of just two submarines between April and May. The high losses were mainly due to the hesitant introduction of convoy systems to protect transatlantic shipping. But the initially missing shoreline darkening also played its part, since without this the ships stood out clearly against the bright silhouettes of American villages and cities such as Atlantic City . Such a blackout was first ordered in 1942.

The cumulative effect of this campaign was extremely severe - a quarter of all ships in World War II were sunk off the east coast of the United States; a total of 3.1 million tons. There were several reasons for this. The naval commander, Admiral Ernest J. King , was unwilling to comply with the British recommendation to introduce convoys. Furthermore, the patrols of the Coast Guard and Navy were predictable and easily evasive, the cooperation between the individual departments was insufficient and the US Navy did not have enough suitable ships, whereupon British and Canadian warships had to be requested for support.

Further course of the war

Several Allied ships were torpedoed within sight of large cities on the American east coast, such as New York City or Boston . The only documented sinking of a German submarine off the east coast of the United States occurred on May 5, 1945, when U-853 sank the Collier Black Point off Newport (Rhode Island) . When the Black Point was hit, the US Navy immediately began chasing and dropping depth charges. When an oil slick and floating debris were found the next day , it was confirmed that U-853 and its entire crew had been sunk. In recent years the wreck has become a popular diving spot. Its intact hull with the hatches open is about 40 m deep, very close to Block Island . In 1991 a wreck was found off the coast of New Jersey, which in 1997 was identified as the remnant of U-869 . Until then, it was assumed that this ship had been sunk off Rabat , Morocco .

Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean

As the convoy tactic took off in the Atlantic, the number of sunk ships decreased and the submarine attacks shifted to the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean . Between 1942 and 1943, more than 20 submarines operated in the Gulf of Mexico. They attacked oil tankers in Texas and Louisiana and sank 56 ships. At the end of 1943 the attacks declined when the merchant ships began to move in armed convoys here too.

On February 16, 1942, a German submarine shelled a Standard Oil refinery and several ships in the mouth of Lake Maracaibo on the island of Aruba, which was then under Dutch rule (→ attack on Aruba ). Three tankers including the Venezuelan Monagas were sunk. The Venezuelan gunboat General Urbaneta helped rescue the crew.

On March 2, 1942, the island of Mona, about 65 km from Puerto Rico , was shelled by a German submarine. There was no damage or human loss.

On April 19, 1942, an oil refinery on Curaçao was shelled.

In one case, the tanker Virginia was attacked by the German submarine U-507 in the mouth of the Mississippi River . On May 12, 1942, 26 crew members died and 14 survived.

U-166 was the only submarine that was sunk in the Gulf of Mexico during the war. At first it was assumed that the ship had been sunk on August 1, 1942 by a Grumman G-44 torpedo of the US Coast Guard. It is now believed that U-166 was hit by a depth chargedropped bya Robert E. Lee escort two days earlier. The G-44 is believedto be chasinganother submarine, U-171 , which was also operating in the area at the time. U-166 is now about 1.5 km below its last victim, the SS Robert E. Lee .

Aborted operations by the Axis powers

Japan

Shortly after the attacks on Pearl Harbor, a group of seven Japanese submarines began patrolling the west coast of the United States . It was planned to attack targets off the California coast for Christmas 1941. However, for fear of American retaliation, the attack was initially postponed to December 27 and later abandoned entirely.

Already in the early stages of the Pacific War , plans were drawn up on the Japanese side for an attack on the Panama Canal . This important water passage in Panama was mainly used by the Allies for replenishment during World War II. However, the planned Japanese attack never started because the Japanese Imperial Navy suffered painful losses at the beginning of the conflict with the United States and the United Kingdom.

1942 launched the Imperial Japanese Army , the Z project (also called "Project Z-Bomber" called). This should produce an intercontinental bomber similar to the German America bomber , which should be able to reach North America from Japan. This aircraft was to have six 5,000 horsepower engines, which Nakajima Hikōki began to develop . The aim was to double the output of the HA-44 engine (the most powerful engine available in Japan at the time) to a 36-cylinder engine. Designs were presented to the Imperial Japanese Army in the form of Nakajima G10N , Kawasaki Ki-91 , and Nakajima G-5N models. Except for the G5N, none of these models got beyond prototype status. In 1945 "Project Z" and other projects to develop heavy bombers were canceled.

Italy

The Kingdom of Italy developed a plan to attack New York Harbor with submarines. However, when the Italian situation continued to deteriorate during the war, it was postponed and later discarded.

Germany

In 1940, the Reich Aviation Ministry requested plans for the America bomber program from German aircraft manufacturers. In this a long-range bomber should be developed with which an attack on the United States from the Azores should be made possible. The planning phase ended in 1942; however, the project was too expensive to be completed.

False alarm

The following false alarms are largely due to a lack of military and civilian experience with the war itself and the poor radar technology available at the time. Some critics speculate that these were deliberate attempts by the Army to frighten the population in order to increase interest in the preparations for war.

The days after Pearl Harbor

On December 8, 1941, due to rumors of an enemy aircraft carrier off the coast of San Francisco in Oakland , California, all schools were closed and blackout and radio silence was ordered in the evening . These reports of an attack on San Francisco have been deemed credible in Washington . When the suspicion was not confirmed, many people spoke of a "test". Lt. Gene. John L. DeWitt of the Western Defense Command then said:

“There were planes over this parish last night. They were enemy planes! I mean Japanese planes! And they were followed out to sea. You think it was a hoax ? It's bloody bullshit that sane people think the Army and Navy are doing such a hoax on San Francisco. "

On December 9th, a similar incident occurred in the northeast. Around noon there were indications that enemy aircraft were barely two hours from the coast. Even if there was no general hysteria , several hunters started from Mitchel Field on Long Island to intercept the "attackers". This was followed by the biggest sell-off on Wall Street since the invasion of France , school children in and around New York were sent home and several radio stations shut down. In Boston , police took large quantities of weapons and ammunition from their stores and distributed them to stations around the city; the industrial establishment was advised to prepare for a raid .

1942 - Battle of Los Angeles

The Battle of Los Angeles is also known as " The Great Los Angeles Air Raid ". The name for the event goes back to contemporary sources and denotes an alleged air raid on the California city of Los Angeles during World War II. The event took place on the night of February 24-25, 1942, less than three months after the United States entered the war and the day after the attack on Ellwood . Initially it was assumed that the American flak barrage was aimed at a Japanese attack, but the United States Secretary of the Navy William F. Knox spoke of a "false alarm" at a press conference a few hours after the event. In 1983 the Office of Air Force History published a report that the events were due to a missing weather balloon, flares, grenade strikes and the ever-present tense situation during the war ("War Nerves"). General George C. Marshall believed that the air defense was alerted by civilian planes that might deliberately panic. Several buildings and vehicles were damaged by shrapnel during the action. A total of five people died in car accidents and cardiovascular failure as an indirect result of the fighting.

Based on eyewitness reports and press photos, some ufologists are of the opinion that the objects seen were flight objects of extraterrestrial origin. The event is described by ufologists as one of the largest mass sightings of a flight object of extraterrestrial origin. "The Battle of Los Angeles" was the model for Steven Spielberg's 1941 film - Where Please Go to Hollywood . A retouched press photo of the event and an adapted newspaper headline were used in the trailer for the Hollywood film Battle: Los Angeles .

Eyewitness accounts

Eyewitnesses reported that on the evening of February 24, 1942 the daily air raid drill took place. The stationed American flak positions fired a few shots into the sky as training for emergencies until around 10 p.m. At around 3:15 a.m., the air alarm was triggered again and the stationed flak positions opened fire on one or more visible objects over Los Angeles. The largest object was illuminated by spotlights and could thus be photographed through the local media. Eyewitnesses described the largest object as "silvery and candy-shaped". The shelling by the flak positions ended around 4 a.m. after eyewitness reports said the objects had disappeared in the direction of the Pacific. According to the military, over 1,400 projectiles were fired at the event. American planes are said not to have been used. However, contemporary witnesses report the crash of an American plane near South Vermont Avenue in the city of Los Angeles.

More alarms

A series of alarms occurred in the San Francisco Bay Area in May and June :

- May 12th: A 25-minute air raid alarm is triggered .

- May 27: The West Coast defense was put on alert when cryptanalysts found the Japanese were planning a series of hit-and-run attacks in retaliation for the Doolittle raid .

- May 31: Battleships USS Colorado and USS Maryland left the Golden Gate to form a line of defense to protect against any attack on San Francisco.

On June 2, there was a two-minute air raid alarm, including radio silence from Mexico to Canada until 9:22 pm .

Web links

- Japanese Submarine Attacks on Curry County in World War II ( Japanese submarine attacks ) ( Memento of 22 June 2013 Internet Archive ) on portorfordlifeboatstation.org (English)

- German Espionage and Sabotage Against the US in World War II: George John Dasch and the Nazi Saboteurs (FBI Handout) ( Deutsche Sabotageaktionen Dasch ) ( Memento from December 15, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) on history.navy.mil (English)

- The planned Italian attack on New York Harbor.

- The San Francisco Bay Area at war.

- Army reactions

- Details of the German spies who landed in North America

- Red White Black & Blue - Feature documentary about the Battle of Atu in the Aleutian Islands during World War II

- Defense of the Americas - a publication by the United States Army Center of Military History .

- The battle for the Gulf of Saint Lawrence

Literature, references

- Michael Dobbs: Saboteurs: The Nazi Raid on America. 2004, ISBN 0-375-41470-3 .

- JP Duffy : TARGET: AMERICA, Hitler's Plan to Attack the United States. Praeger Publishers. PB: The Lyons Press.

- Erich Gimpel: Agent 146: The True Story of a Nazi Spy in America. 2003, ISBN 0-312-30797-7 .

- Manfred Griehl: Luftwaffe over America: The Secret Plans to Bomb the United States in World War II. 2004.

- Michael L. Hadley: Submarines versus Canada. ES Mittler & Sohn, Herford and Bonn 1990, ISBN 3-8132-0333-6 .

- Steve Hoern: The Second Attack on Pearl Harbor: Operation K And Other Japanese Attempts to Bomb America in World War II. Naval Institute Press, 2005, ISBN 1-59114-388-8 .

- Robert C. Mikesh: Japan's World War II Balloon Bomb Attacks on North America. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1973.

- Gregory D. Kesich: 1944: When spies came to Maine. Portland Press Herald, April 13, 2003.

- Bert Webber: Silent Siege: Japanese Attacks Against North America in World War II. Ye Galleon Press, Fairfield, Washington 1984, ISBN 0-87770-318-3 .

Individual evidence

- ^ The Shelling of Ellwood. The California State Military Museum.

- ^ Donald J. Young: Phantom Japanese Raid on Los Angeles. In: World War II Magazine , September 2003.

- ↑ SENSUIKAN! - HJMS Submarine I-26: Tabular Record of Movement. combinedfleet.com.

- ^ Stetson Conn, Engelmann, Byron Fairchild (1964, 2000). The Continental Defense Commands After Pearl Harbor. Guarding the United States and its Outposts. United States Army Center of Military History . CMH Pub 4-2.

- ^ Japanese Submarines on the West Coast of Canada. ( Memento of the original from October 7, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. pinetreeline.org.

- ↑ SENSUIKAN! - HIJMS Submarine I-25: Tabular Record of Movement. combinedfleet.com.

- ↑ David Kravets: May 5, 1945: Japanese Bomb Kills 6 in Oregon. Wired .com.

- ^ Clement Wood: The man who killed Kitchener, the life of Fritz Jouber Duquesne. William Faro, inc., New York 1932.

- ↑ Jonathan Wallace: Military Tribunals. spectacle.org.

- ↑ Agents delivered by U-boat ( Memento from November 4, 2005 in the Internet Archive ). uboatwar.net.

- ↑ W. An. Swanberg: The spies who came in from the sea ( Memento of the original from December 26, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , 21, American Heritage Magazine, April 1970.

- ↑ James W. Essex, 2004. Victory in the St. Lawrence: the unknown submarine war. Boston Mills Press, Erin, Ontario 2004.

- ^ A b Michael L. Hadley: Chapter five, The Intelligence Gatherers: Langbein, Janow and Kurt. U-Boats Against Canada: German Submarines in Canadian Waters. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP, 1990, ISBN 0-7735-0801-5 , pp. 144-167.

- ^ Weather Station Kurt. itod.com, March 27, 2005.

- ↑ Michael L. Hadley: Submarines against Canada. ES Mittler & Sohn, Herford and Bonn 1990, ISBN 3-8132-0333-6 , pp. 41-42.

- ↑ Farley Mowat: GRAY SEAS UNDER. Ballantine Books, New York 1966.

- ^ Robert Leckie: The Story of World War II. Random House, New York 1964, p. 100.

- ↑ Michael Salvarezza, Christopher Weaver: On Final Attack, The story of the U853. ecophotoexplorers.com.

- ^ Hitler's Lost Sub. Transcript. NOVA , PBS. November 14, 2000.

- ↑ a b World War II Shipwrecks. ( Memento of the original from September 5, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. US Department of Interior, Minerals Management Service, Gulf of Mexico Region.

- ^ Shells at Aruba. In: Time magazine, February 23, 1942.

- ↑ Robert L. Schenia: Latin America: A Naval History 1810-1987. Naval Institute Press , Annapolis, Maryland, United States, ISBN 0-87021-295-8 .

- ↑ Steve Horn: The Second Attack on Pearl Harbor: Operation K and Other Japanese Attempts to Bomb America in World War II. Naval Institute Press, 2005, ISBN 1-59114-388-8 , p. 265.

- ^ Christiane D'Adamo: Operations. In: Regia Marina Italiana .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h THE ARMY AIR FORCES IN WORLD WAR II; DEFENSE OF THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE. The Virtual Museum of The City of San Francisco.

- ↑ John Caughey, Laree Caughey: Los Angeles: biography of a city. University of California Press, 1977, ISBN 0-520-03410-4 .

- ↑ John E. Farley: Earthquake fears, predictions, and preparations in mid-America. Southern Illinois University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-8093-2201-3 .

- ^ California and the Second World War; The Battle of Los Angeles. The California State Military Museum.

- ^ The Battle of Los Angeles. Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco.

- ^ California in World War II: The Battle of Los Angeles . Militarymuseum.org. February 25, 1942. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- ^ Brian Niiya: Japanese American History: An A-to-Z Reference from 1868 to the Present. VNR AG, 1993, ISBN 0-8160-2680-7 , p. 112.

- ^ Greg Bishop, Joe Oesterle, Mike Marinacci: Weird California . Sterling Publishing , March 2, 2008, ISBN 978-1-4027-3384-0 .

- ↑ Terrenz Sword: The Battle of Los Angeles, 1942: The Mystery Air Raid . CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform , August 18, 2010, ISBN 1-4528-8515-X .

- ^ Larry Harnisch: Another Good Story Ruined - The Battle of Los Angeles . In: Los Angeles Times , February 21, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ A b C. Scott Littleton: 2500 Strand - Growing up in Hermosa Beach, California, During World War II . Red Pill Press , ISBN 978-1-897244-33-3 .