Adder

| Adder | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Adder ( Vipera berus ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Vipera berus | ||||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) | ||||||||||||

| Subspecies | ||||||||||||

|

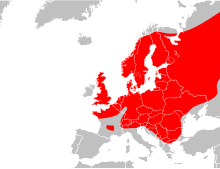

The adder ( Vipera berus ) is a small to medium-sized venomous snake of Eurasia from the family of vipers (Viperidae). Of all vipers, it has the largest and at the same time the most northerly range, and it is the only snake species that can also be found north of the Arctic Circle .

features

Dimensions and shape

The adder reaches an average length between 50 and 70 centimeters, but in extreme cases can also be up to 90 centimeters long. The largest adder found in Germany was a female of 87 centimeters in Thuringia . For the area of the former Soviet Union , 84 centimeters is documented as the maximum size, for England, however, only 73 centimeters. The longest specimens mentioned come from Northern Europe with one individual from Northern Finland with 94 centimeters and one from Central Sweden with 104 centimeters in length; however, both cases are not confirmed. The females are usually significantly longer than the males, who usually do not exceed a body length of 60 centimeters. In contrast, the length of the tail is greater in the males in relation to the body length than in the females. The weight of the animals is on average 100 to 200 grams with maximum values up to about 300 grams in pregnant females.

The body of the snake is compact, the head for a viper is comparatively little distinct from the body. The snout is rounded in front and merges into a flat top of the head, the canthus rostralis is also rounded. The head is oval when viewed from the top and slightly broadened at the back of the head by the poison glands. As an adaptation to cool living spaces, it is able to broaden its body by actively spreading the ribs in order to offer a larger area for heat absorption when sunbathing and thus to use less heat radiation more effectively.

coloring

The basic color of the adder is very variable and ranges from silver-gray and yellow to light and dark gray, brown, blue-gray, orange, red-brown and copper-red to black. The coloration is very variable within the species; different colors can also appear within the same population . In large parts of the distribution area, the animals show a sexual dichromatism . Males usually have different shades of gray from white-gray to almost black, and the contrast between the basic color and the drawing is usually more pronounced in them than in the females. Different shades of brown, red or beige predominate in the females, and the contrast between the light basic color and the dark zigzag band is usually a little less.

The most noticeable drawing feature is a dark zigzag band on the back. Just like the basic color, the drawing on the back can also be made very variable. The variations range from wide or narrow zigzag lines through wavy and diamond bands to individual cross ties, as they are especially in the subspecies V. b. bosniensis are trained. In Austria and Slovenia in particular, there are also populations that have a dark basic color with light or light bordered markings. There are also a number of dark, round spots on the flanks. It is not uncommon for smooth snakes to be mistaken for adders.

In addition to the drawn color variants, there are also monochrome specimens of the adder. The hell viper , also known as mountain viper in the Alpine region, is a black adder ( melanistic color ). Just like the hell viper , the copper otter , a purely copper-colored variant, used to be considered a species of its own. Most specimens of the infernal (mountain viper) or copper viper are not black or red from birth, but gradually darken or ruby in the first two years of life. The black coloration seems to occur more frequently in cooler areas, for example in Northern Europe, in moor areas or in mountains, than in warmer areas. Locally, more than 50% or even 70 to 95% of the population can be melanistically colored. Partially melanistic and albinotic animals, on the other hand, are very rare, but have also been documented.

The head usually has the same basic color as the body, especially in the females the rostral and canthus rostralis can be slightly yellowish brown. At the back of the head the animals have an x-shaped or a V-shaped drawing with the tip pointing towards the head, which is separated from the zigzag band on the back. A wide band of temples stretches across the eyes to the neck. The vertically slit pupils , which are surrounded by a rust-red iris , are typical of vipers . The ventral side is gray-brown, black-brown or black and often has lighter spots, especially on the throat and chin region. The underside of the tip of the tail can be yellow, orange, or brick red.

Scaling

With the exception of the bottom row, the back scales of the adder are clearly keeled and have a rough surface. As a rule, there are 21 rows of back scales around the middle of the body, in rare cases there are 19 or 23. The ventral side is formed from 132 to 152 in males and from 132 to 158 in females from ventral shields , which are the anal shield and 29 to 48 (males ) or 23 to 43 (females) paired under tail shields .

The scaling of the head can be very variable in the adder. The top of the head is covered with many small scales, the unpaired forehead shield (frontal) and the pair of crown shields (parietal) are large and fully developed. Between the eye and the eight to nine, more rarely six to ten, upper lip shields ( supralabials ), the snake usually has a series of under-eye scales ( suboculars ); in rare cases two rows can be formed. The rostral is almost square and just visible from above. The nostril lies entirely in an undivided nasal shield , which is separated from the rostral by a nasorostral . The temporalia are smooth and only slightly keeled. The lower edge of the mouth is formed by three to four, rarely five, sublabials .

Karyotype

The karyotype of the adder, with 18 pairs of chromosomes (2n = 36), 8 of which are very large ( macrochromosomes ), corresponds to that of most of the viper species examined. The only exceptions to this are the aspis viper ( V. aspis ) and the European horned viper ( V. ammodytes ) with 21 chromosome pairs (2n = 42) and 11 macrochromosome sets. Females have two different sex chromosomes , which snakes call the Z and W chromosomes, while the males have two Z chromosomes.

distribution and habitat

distribution

Of all vipers, the adder has the largest and at the same time the northernmost range, and it is the only snake species that can also be found north of the Arctic Circle . The area ranges from central and northern Europe , including the UK and Scandinavia over the Alpine area and the northern Balkans , Poland , Hungary , the Czech Republic and the entire northern Russia as far as Sakhalin in eastern Asia. The snake can also be found in North Korea and in northern Mongolia and China .

In Germany it is mainly in the North German Plain (especially in heath areas), in the eastern mountain ranges and in parts of southern Germany (eg. Black Forest , Swabian Alb , Bavarian Forest , Alpine with foreland ) before; in between there are larger gaps in the area, especially in the climatically warmer river valleys. The lack of climatically suitable western low mountain ranges ( Sauerland , Bergisches Land , Siegerland , Westerwald , Vogelsberg , Taunus , Hunsrück , North Palatinate Bergland , Palatinate Forest and Odenwald ) is striking . Because the species is seriously threatened in the other areas in its portfolio, it is in all of Germany under nature conservation . Larger populations can be found in particular on Hiddensee and Rügen .

In Austria the adder is widespread in all federal states except Vienna and Burgenland . In the Alps it inhabits areas up to an altitude of about 2500 meters. The adder is absent in the Pannonian lowlands and in south-east Austria . There are larger local deposits in the Mühlviertel and Waldviertel .

In Switzerland , the species occurs mainly in the Alpine region , especially in the east. In the western Alps it is much rarer than the aspic viper - because for the most part the habitats of the aspic viper and adder are mutually exclusive. It occurs very locally in eastern Ticino and in the cantons of Graubünden , Bern , Vaud , Friborg and Jura . It has not yet been clarified whether the adder ever made its home in the canton of Valais or whether it was ousted by the aspic viper over time. To meet an adder in the German-speaking Valais would be a big surprise.

habitat

The adder prefers habitats with strong day-night temperature fluctuations and high humidity. Dwarf shrub-rich forest aisles and forest edges, moors, heaths, moist lowlands, alpine scree fields and mountain meadows in the area of the tree line are settled. In the mountains you can find the snake up to heights of 2500 to 3000 meters.

Way of life

activity

The adder is diurnal and only shifts its activity to dusk when it is very hot. Morning and late afternoon sun it seeks suitable places and basks, the optimal activity temperature reaches about 30 to 33 ° C . It is particularly active on hot humid days and after long periods of rain, but it is very sensitive to wind. When disturbed and threatened, the snake flees under stones or in the vegetation. If she is cornered, threatening gestures with loud hissing and bites occur, causing her upper body to snap forward.

The adder bridges the winter with a four to seven month long, in the extreme north even up to eight months of cold rigidity . She looks for suitable hiding spots and often hibernates in common quarters with many other adders and other reptiles. In Germany, rigid winter usually begins in mid to late October, and in warm years only in early November. Depending on the weather and altitude, the first animals appear in Germany from mid-February to April, regionally later, from their rigor. The males appear on average two weeks before the females.

nutrition

Like most other vipers, the adder is a stalker and does not specialize in particular prey. The prey animals are attacked with a bite through which the viper venom is injected into the body. Then the adder pauses briefly and then begins to pursue the bitten animal, which is very weakened due to the poisonous effect and eventually dies. The prey animals are swallowed completely, mostly head first.

The adder mainly hunts small mammals , lizards and frogs . Among the small mammals, long-tailed mice , voles and shrews make up the largest proportion of prey. The individual prey spectrum is strongly dependent on the local offer, which means that the main prey animals vary greatly. Thus, there is approximately in the range of archipelago in Southern a strong dependence on the earth mouse ( Microtus agrestis ) in the forests of central Europe by the bank vole ( Clethrionomys glareolus ) and in marshy wetlands of brown frogs such as the frog ( Rana temporaria ) and the Moorfrosch ( Rana arvalis ). In contrast to the adults, the young snakes feed almost exclusively on young brown frogs and forest lizards , which is why these species play a central role in the distribution of the adder.

Reproduction and development

The adders mate in April to May after rigid winter and spring molt. During the mating season, the competing males have comment fights , with the rivals straightening their front bodies and trying to push the opponent to the ground. The pairing itself is preceded by a long foreplay .

The adder is one of the few ovoviviparous reptiles , which means that it incubates its eggs in the womb. This peculiarity is to be understood as a further adaptation of the adder to cool northern habitats (see distribution area), since in this way the eggs in the mother animal are constantly exposed to the warming rays of the sun. In a conventional clutch, the period with sufficiently high summer temperatures for the young animals to develop would be too short. The eggs only form a thin membrane that is pierced by the young snakes during or immediately after birth. As with all reptiles, the embryo feeds on the egg yolk in the egg. The mother organism takes care of the gas exchange.

The young snakes are born between August and October, when they are barely the size of a pencil. The average litter size is 5 to 15, in rare cases there are up to 20 young animals. The first molt occurs shortly after birth, after which the snakes are independently active and hunt for young frogs and lizards. Adders reach sexual maturity at three to four years of age.

Enemies

A number of birds of prey and mammals are important as predators of the adder , but also a few reptiles .

Among the birds of prey is the Buzzard ( Buteo buteo ), the meadow ( Circus pygargus ) and the harrier ( Circus aeruginosus ), the black kite ( Milvus migrans ), the Schell ( Aquila clanga ) and the Schreiadler ( Aquila pomarina ) and the Schlangenadler ( Circaetus gallicus ) proven to be a snake hunter. The eagle owl ( Bubo bubo ), the carrion crow ( Corvus corone ), the gray heron ( Ardea cinerea ), the white stork ( Ciconia ciconia ), the crane ( Grus grus ) and the domestic chicken ( Gallus gallus ) can also prey on adders.

Among the mammals, different species of marten such as the European polecat ( Mustela putorius ), the ermine ( Mustela erminea ), the European badger ( Meles meles ) or the fire weasel ( Mustela sibirica ) can be named as predators. The red fox ( Vulpes vulpes ), the brown-breasted hedgehog ( Erinaceus europaeus ) and the house cat are also important. The wild boar ( Sus scrofa ) plays a special role, causing a strong predation pressure on snake populations due to the increasing populations in large parts of Central Europe. For example, for the Central Apennines in Italy, it has been proven that the snake density in wild boar-free areas is up to three times as high as in comparable areas with wild boar.

Among the reptiles, the grass snake ( Natrix natrix ) and the dice snake ( Natrix tessellata ) come into question as predators, especially for young snakes. Conversely, however, both species are also preyed on by adult adders.

Evolution and systematics

Research history

The first scientific description of the adder was made by Carl von Linné in his tenth edition of the Systema naturae in 1758 under the two different names Coluber Berus and Coluber chersea and in 1761 in the subsequent edition also under Coluber prester . Albertus Seba used the generic name Vipera as early as 1734 and thus before the introduction of the binominal naming system Linnaeus , which Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti confirmed in 1764. François-Marie Daudin introduced the species name Vipera berus , which is still valid today, in 1803.

Current system

The current differentiation of the adder from similar species is mainly based on the scaling ( pholidosis ), especially on the signs on the top of the head. In the North Iberian adder ( Vipera seoanei ) , for example, the shields on the top of the head (frontal and parietal) are almost completely present in the adder. Differences at the molecular level as well as in the poison composition justify the species distinction.

The adder is systematically classified in the genus Vipera and there often together with a few other species in the subgenus Pelias . A comparison of the mitochondrial DNA ( mtDNA ) in 2000 confirmed the close relationship between the North Iberian adder and the adder. Here both species are sister species. According to the analysis, the closest relatives were the western Caucasus viper ( V. dinniki ) and the European horned viper ( V. ammodytes ). However, the analysis did not include all species of the genus Vipera , so that no phylogenetic conclusions can be drawn for the entire genus. Svetlana Kalyabina et al. in 2002 posed a relationship analysis on the basis of mitochondrial DNA before, after which the adder together with the Vipera Nikolskii ( V. Nikolskii ), Baran's Viper ( V. barani ) and the Ponti's viper ( Vipera pontica ) forms a monophyletic group, the sister species the Nordiberische Adder is. Until 1986 the forest steppe otters, Baran's vipers and Pontic vipers were almost unanimously classified as adder races , the independence as a species postulated by V. N. Grubant and A. V. Rudaeva is still controversial among systematics today .

Historical biogeography

In contrast to most other vipers, there are good fossil records in the case of the adder, which enable both the reconstruction of the lineages and the biogeographical development. The oldest fossils that can be clearly assigned to the adder come from the early Miocene and were found in Langenau in the lower Orleanium and in the Randecker Maar in the middle Orleanium. Finds from Eastern and Central Europe come from the middle and late Miocene, and the adder is documented in a large part of its current range for the Pleistocene . Finds from Poland, East England, Austria, Romania and Germany should be mentioned in particular.

In addition to the fossils, molecular biological data help to reconstruct the historical biogeography and the distribution in the Pleistocene . A systematic analysis of the genetic material of snakes in the entire area of distribution showed how the European adder colonized Europe after the Vistula Ice Age with its extensive glaciation of the European continent. The study comes to the conclusion that this settlement came from three separate founder populations who lived in different retreat areas.

Snake venom

Composition and effect

Adders are very shy. In case of danger, they flee immediately. A bite only occurs if you threaten it massively, touch it or step on it. The LD 50 value of the poison is around 6.45 mg (milligrams) per kilogram of body mass for a subcutaneous injection and around 0.55 mg per kilogram of body mass for an injection into a blood vessel. For a person of 75 kg (kilograms) body mass, this means that he would achieve a lethal dose of 483.75 mg or 41.25 mg of the poison when injected, which would correspond to the average bite of more than five adders. Therefore, deaths from adder bites alone are unlikely. Since the adder does not simply waste the poisonous secretion it needs to hunt mice, frogs, blindworms or other animals, it also uses little or no poison from its small supply for most of its defense bites.

Although the venom of the adder is about two to three times more venomous than that of the diamond rattlesnake ( Crotalus adamanteus ), a bite is usually only dangerous for children and the elderly due to their low venom supply of only 10 to 18 mg dry weight. The symptoms of the bite express themselves as follows: Around an hour later there is a large swelling around the bite. Due to nerve agents can cause shortness of breath and heart problems. The bite of an adder can also lead to paralysis. Because of the blood-decomposing part of the secretion, it is possible that the area near the bite site looks bluish.

Often, however, these symptoms do not occur at all, and the pain from the bite is usually limited, so that some people do not even notice when they are bitten. Conversely, however, more serious cases have also been documented: Between 2003 and 2009, 23 people on the island of Hiddensee alone had to be treated in hospital for several days after an adder bite, in two cases even in the intensive care unit.

Epidemiology

Between 1959 and 2003, there were no known deaths from an adder bite in Germany. In 2004, an 81-year-old woman died on the island of Rügen after being bitten by a black adder. However, due to the unusually short period of time between the bite and the occurrence of death and her recent hospital stay, it is rather unlikely that the death was caused solely by the effects of the poison.

Human and adder

Hazard and protection

The adder populations are primarily endangered by adverse effects on the habitats, for example through the encroachment or afforestation of sunny spots or through management or construction measures in heather and forest edge areas. In East Germany, especially due to the abandonment of the clear-cutting economy, sunny areas that were otherwise used as spring sunbathing and mating spots are becoming increasingly rare in the forest. Active biotope development measures are therefore required in these forests to protect the adder. Another reason for the great endangerment of the adder is the increasing fragmentation of the forests by trunk roads. The trapped populations are threatened with genetic impoverishment and, in the long term, local extinction.

In earlier decades many populations were reduced considerably by the massive killing of animals (supported by state “head premiums” per specimen hunted). Reptiles are often pushed into the peripheral areas through rewetting measures in partially drained raised bogs .

Legal protection status (selection)

- Fauna-Flora-Habitat Directive (FFH-RL): not listed

- Federal Species Protection Ordinance (BArtSchV): Appendix 1

- Federal Nature Conservation Act (BNatSchG): particularly protected

National Red List classifications (selection)

- Red List Federal Republic of Germany: 2 - highly endangered

- Red list of Austria: VU (corresponds to: endangered)

- Red list of Switzerland: EN (corresponds to: highly endangered)

Like all European snake species, it is listed in Appendix II of the Bern Convention ( Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Wildlife and Their Natural Habitats ) and thus enjoys strict protection within the European Union . The animals may neither be killed nor caught; Owners of this type of snake must submit appropriate certificates of origin and offspring.

Cultural history

There was also a popular superstition that red or black adders are particularly poisonous.

The adder was often caught as a medicine for humans and animals. In Lithuania , for example, chopped up adders were fed to pigs in the belief that they would grow better as a result.

supporting documents

Individual evidence

Most of the information in this article has been taken from the sources given under literature; the following sources are also cited:

- ↑ a b c d e All information according to Nilson et al. 2005

- ^ A b Hans-Jürgen Biella, Wolfgang Völkl: The biology of the adder (Vipera berus, L. 1758) in Central Europe - a brief overview. In: Michael Gruschwitz, Paul M. Kornacker, Richard Podloucky, Wolfgang Völkl, Michael Waitzmann (Eds.): Distribution, ecology and protection of snakes in Germany and neighboring areas. Mertens distribution, ecology and protection of snakes in Germany and adjacent areas. Mertensiella 3, 1993

- ↑ Michel Gruschwitz, Paul M. Kornacker, Michel Waitzmann, Richard Podloucky, Klemens Fritz & Rainer Günther: The snakes of Germany - distribution and stock situation in the individual federal states In: Michael Gruschwitz, Paul M. Kornacker, Richard Podloucky, Wolfgang Völkl, Michael Waitzmann (Ed.): Distribution, ecology and protection of snakes in Germany and neighboring areas. Mertensiella 3, 1993

- ↑ Atlas of amphibians and reptiles in Europe: Distribution map Vipera berus (PDF file; 386 kB): Homepage of the Societas Europaea Herpetologica

- ↑ Andreas Meyer, Department of Reptiles, KARCH (coordination office for amphibian and reptile protection in Switzerland). In: Sabine Joss, Fredy Joss (2008): Hiking destination summit - Upper Valais. SAC publishing house, Bern. ISBN 3-859-02275-X

- ↑ Wolfgang Völkl, Hans-Joachim Clausnitzer, Arno Geiger, Ulrich Joger, Richard Podloucky, Steffen Teufert: Kreuzotterschutz, Jagd und Forstwirtschaft. In: Ulrich Joger, Ralf Wollesen (Hrsg.): Distribution, ecology and protection of the adder ( Vipera berus [Linnaeus 1758]) . Mertensiella 15, 2004

- ↑ Species list according to Andrey Bakiev: About the food relations of the adder (Vipera berus) in the central Volga region as predator and prey of vertebrates . In: Ulrich Joger, Ralf Wollesen (Hrsg.): Distribution, ecology and protection of the adder ( Vipera berus [Linnaeus 1758]) . Mertensiella 15, 2004

- ↑ P. Lenk, S. Kalayabina, M. Wink, U. Joger (2001): Evolutionary relationships among the true vipers (Reptilia: Viperidae) inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 19: 94-104. ( Full text PDF )

- ↑ Svetlana Kalyabina-heaps, Silke Schweiger, Ulrich Joger, Werner Mayer, Nicolai Orlov, Michael Wink: phylogeny and systematics of the adders (Vipera berus complex). In: Distribution, ecology and protection of the adder (Vipera berus). Mertensiella 15, 2004 ( summary of the conference report )

- ↑ Sylvain Ursenbacher, Malin Carlsson, Véronique Helfer, Håkan Tegelström, Luca Fumagalli: Phylogeography and Pleistocene refugia of the adder ( Vipera berus ) as inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequence data. In: Molecular Ecology 15, 2006; Pp. 3425-3437, Wiley Online Library , Semantic Scholar , doi: 10.1111 / j.1365-294X.2006.03031.x

- ↑ Falk Ortlieb et al. 2012

- ↑ poison advising the University of Freiburg : locals poisonous snakes , accessed September 10, 2015

- ↑ Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (ed.): Red list of endangered animals, plants and fungi in Germany 1: Vertebrates. Landwirtschaftsverlag, Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3784350332

- ↑ Online overview at www.amphibienschutz.de

- ↑ Appendix II of the Bern Convention

literature

- Göran Nilson, Claes Andrén, Wolfgang Völkl: Vipera (Pelias) berus (Linnaeus, 1758) - adder. In: Ulrich Joger, Nikolaus Stümpel: Snakes (Serpentes) III Viperidae. in the series Manual of Reptiles and Amphibians in Europe Volume 3 / IIB. Aula-Verlag, Wiebelsheim 2005; Pp. 213-292. ISBN 3-89104-617-0

- Hans Schiemenz, Hans-Jürgen Biella, Rainer Günther, Wolfgang Völkl: Kreuzotter - Vipera berus (Linnaeus, 1758). In: Rainer Günther (Ed.): The amphibians and reptiles of Germany. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Jena 1996; Pp. 710-728. ISBN 3-437-35016-1

- David Mallow, David Ludwig, Göran Nilson: True Vipers. Natural History and Toxicology of Old World Vipers. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar (Florida) 2003; . 242-252. ISBN 0-89464-877-2

- Hans Schiemenz: The adder. Neue Brehm-Bücherei Volume 332, Westarp Sciences, Hohenwarsleben 1995. ISBN 3-89432-151-2

- Ulrich Joger, Ralf Wollesen (Ed.): Distribution, ecology and protection of the adder (Vipera berus). Mertensiella 15, 2004; ISBN 3-9806577-6-0

- Ulrich Gruber: The snakes in Europe and around the Mediterranean. Franckh'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung Stuttgart 1989; Pp. 193-194. ISBN 3-440-05753-4

- Falk Ortlieb, Andreas Dunst, Fanny Mundt, Irmgard Blindow, Klaus Fischer: Bite injuries caused by adders ( Vipera berus ) on the island of Hiddensee (Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania) in the years 2003–2009 . In: Zeitschrift für Feldherpetologie 19 (2012), pp. 165–174, PDF or PDF , English Human bite injuries by adder ( Vipera berus ) on the island of Hiddensee (NE Germany) during 2003 to 2009 .

Web links

- The adder in Austria on www.herpetofauna.at: Species description, distribution and pictures

- Viper in the Animal Diversity Web (Engl.)

- Report on the international conference "Ecology and protection of the adder" 2002 in Darmstadt

- Page about the adder at reptilien-brauchen-freunde.de

- Page about the adder at KARCH (coordination office for amphibian and reptile protection in Switzerland)

- Poison Control Center (also has pictures)

- Photos of the adder on www.herp.it

- Adder distribution in Europe

- Vipera berus in The Reptile Database