Old town (Schweinfurt)

|

Old town

District in Schweinfurt

Coordinates: 50 ° 2 ′ 42 ″ N , 10 ° 14 ′ 3 ″ E

|

|

|---|---|

| Height : | 220 m above sea level NN |

| Area : | 40 ha |

| Residents : | 2529 (December 31, 2015) |

| Population density : | 6,323 inhabitants / km² |

| Postal code : | 97421 |

| Area code : | 09721 |

|

Martin-Luther-Platz

St. Johannis and Altes Gymnasium (left) |

|

The old town is part of the independent city of Schweinfurt . Due to the lack of an official city structure and the city administration not having published its subdivision of the city area into city districts and districts, it cannot be defined more precisely. From the only publication of the city on this, in connection with the youth welfare plan, it is not clear whether the old town (district 11) is only a district within the city center (districts 11, 12 and 13) or an independent district. The old town is in the east (or east) of the city center.

The old town is surrounded by the city wall, which is still preserved in sections, and in front of it mostly by ring systems. The eastern part of the old town (without its later western extension) with the market square and street cross forms a classic medieval city complex, which is why it is probably a founding city . Presumably, Emperor Friedrich I, Barbarossa had it laid out as Civitas Imperii ( imperial city ) in the 12th century . In competition with the first Schweinfurt settlement on Kiliansberg , which today is also called the old town or, to distinguish it, the old town as it never had town charter. The imperial city was first confirmed in a document by King Wilhelm of Holland in 1254.

The Schweinfurt old town, like the other urban areas outside the industrial area, was preserved to 60% in the Second World War , contrary to the information of most national publications that speak of severe destruction.

location

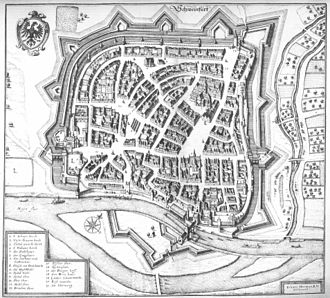

The old town forms the eastern part of the city center district , which already existed during the imperial city period (until the beginning of the 19th century ) when Schweinfurt was bordered by a city wall. The old town is today largely surrounded by ramparts (green areas) and the city wall is still preserved in several sections or has been partially reconstructed. The old town lies on the north bank of the Main and has a natural border through the valley of the Marienbach in the east . Furthermore, the Main Island Bleichrasen can also be counted as part of its area in the broadest sense , as it was integrated into the fortifications that are no longer preserved here (see plan above).

The old town is about 220 to 225 m above sea level. NN on a flood-free base, approx. 12 to 17 m above the Main with 207.6 m above sea level, which is dammed to form the major shipping route ( Rhine-Main-Danube Canal ) . NN at the level of the old town (above the Schweinfurt barrage ). The Schweinfurt Mitte DB stop is located at the south-west corner of the old town .

Overview

Cityscape

Today the old town is characterized by great contrasts. In the far east, the city wall stands in sharp contrast to the massive Rückert Center. In the east, carefully renovated, old Franconian old town quarters follow. In the middle around the Roßmarkt there is urban chaos. In the west around the Jägersbrunnen there is finally a more modern city area. While the Stadtgalerie Schweinfurt further west is already outside the old town.

See also: Schweinfurt, cityscape

Outline of the old town

Inner city: center and right (east)

City expansion: left and above (west)

Fischerrain : lower left corner (southwest)

Below: Main with side arms. Right: Marienbach

The old town is divided into three areas:

- Inner old town : the city was founded around the market square

- Urban expansion : in the west and north

- Fischerrain : fishing settlement annexed in 1436

The old town in the narrower sense, still predominantly historical, is congruent with the area of the old town renovation . It includes the inner old town, the Fischerrain and the area of the northern urban expansion. The remaining area of the old town in the west is today a predominantly less structured, small to medium-sized area, in parts also a modern city area.

Quarters on the Main

There are three renovated old town quarters of different characters on the Main. Down the Main (from east to west) these are:

- the Zurich in the inner old town. A former castle district and the oldest part of the inner city (on the right map in the lower right corner);

- the former commercial district , also in the inner old town (on the right-hand plan in the lower center);

- the Fischerrain . A once independent fishing settlement of unknown age and origin (on the right plan in the lower left corner).

Marketplaces

Schweinfurt is known as the city of squares , with five former marketplaces in the old town. Today market days are only held on the (main) market.

- market

- Albrecht-Dürer-Platz - former name: Holzmarkt ¹

- At the armory - former name: Schweinmarkt ¹

- Kornmarkt - former name: Getreidmarkt ¹, previously: Salzmarkt ², before 1806 a leather and shoe market ²

- Roßmarkt - former name: Viehmarkt ²

¹ in the cadastral plan from 1868

² Peter Hofmann: schweinfurtfuehrer.de

history

City foundation

For the beginnings of the old town see the article introduction. The oldest building in the city still preserved today is the St. Johanniskirche , Romanesque core , begun before 1200. The first city ruin was already before the first documentary mention, around 1250, in the struggle for supremacy in Main Franconia between the Hennebergers and the bishop of Wurzburg . The second ruin of the city in 1554 happened during the Second Margravial War . After that, the old town was rebuilt in its current form from 1554 to 1615.

The structural development of the presumed founding town began at a right angle between the Main and the valley of the Marienbach . Within these natural limits, the city could only develop on the flood-free plateau, approx. 15 m above the Main, towards the west and north. The first quarter, the Zürch , was built in this corner on the edge of the market square, around which three further quarters were built around the street cross on the market. North of a river, on the sunny side, with four quarters and four city gates (plus fisherman's gate) around a cross on the market square, where the town hall (Markt 1) and the city church face each other. In the imperial city with early democratic approaches, palaces were not welcome. Nobles were not allowed to live in the city with civil rights. The Reichsburg in the old town was demolished in 1427 (see Zurich ).

City expansion

Due to good economic development, the imperial city was able to acquire several villages and lands in 1436/37 (see: Schweinfurt, building a territory ). “ After 1437 a necessary expansion of the city gradually took place in two generations, which by 1502 was fairly complete. “The old town was expanded to the west and north. Until then, the city wall ran northwards from the Main along the following route:

- Petersgasse, southern part (today: Nussgasse )

- Across the area of two blocks of houses that still exist today on both sides of the Rosengasse, which were created after the city's expansion

- Kronengässchen

- Meat Bank, Ostkante (today: Georg-Wichtermann-Platz )

- Kirchgasse

- Bodengasse

Before that, the city moat ran, which the street name Graben indicates. The course of this first, inner city wall with a ditch in front of it is still recognizable today from the arched course of the streets in this area. The foundations of the Inner Hospital Gate not far east of Albrecht-Dürer-Platz in Spitalstraße and the Inner Obertor not far south of the Kornmarkt in Obere Straße were found and the locations were marked.

During the expansion of today's old town, the two alleys Alte Mang (name from 1567, today: Manggasse) and Am Oberen Anger (today: Bauerngasse) were laid out on the arched area immediately outside the inner city fortifications . They were probably laid out as anger , as this explained the unusual width of both streets.

While the original old town had the market as the only large square in its center, four more marketplaces (see marketplaces ) and the meat bank (see: Georg-Wichtermann-Platz ) were added as a result of the city expansion . Topographically, there were no limits to the west and north, and so the old town has unusual proportions for late medieval German conditions, with only two-story town houses ( some of which were raised by one floor in the 18th century ) and a relatively large number of wide, public rooms. This is also reflected in the historical city map (see: Overview ) and is beneficial for fire protection and traffic, which is why the historical city plan has remained almost unchanged to this day. There was no big city fire outside of wars.

In the 1640s, in the course of the Thirty Years' War , which the city survived unscathed, the outdated, medieval city wall was expanded by the Swedes into a modern fortification (see: City wall and ring systems ). This completed the historical cityscape at the end of the Thirty Years War. The following city view from 1648, by Matthäus Merian , is the epitome of historic Schweinfurt to this day.

Modern times

In the 19th century , the city gates were demolished for reasons of traffic engineering, which the Schweinfurt citizens have long viewed as an unforgivable intrusion into the historical cityscape as a result of a false belief in the future. At the center of the criticism is Carl von Schultes , who was mayor of the city for almost the entire second half of the 19th century. The longing for medieval romanticism is particularly pronounced in the industrial city, which is also reflected in the extensive renovations of the old town, with the maintenance and restoration of historical structures (see: Schweinfurt model ). The late medieval old town plan has been preserved to this day, apart from a few widened alleys. There were neither road relocations nor breakthroughs, such as B. 1895/96 in neighboring Würzburg , with the big breakthrough for the new main shopping street Schönbornstrasse. A similar project in Schweinfurt after 1945 was not realized (see: Second World War and the post-war period ).

Construction of the railroad

Due to the difficult topographical framework, three variants for the routing of the Ludwigs-Westbahn were discussed, none of which were ideal:

- Northern variant: Northern bypass of the old town, with a tunnel through the vineyards to the east on the Mainleite from Ludwigsbrunnen and railway embankments (with culverts) over the valleys of the Höllenbach and Marienbach . With a train station on the northern edge of the old town, west of the Obertor.

- Middle variant: tracks through the middle of the city, on Rückertstrasse and Spitalstrasse.

- South variant: A line layout on a narrow strip between the old town and the Main , with only two through tracks, without a train station in this area. With the approx. 95 m long Harmonietunnel with two tubes, north along the Harmonie from 1835, today's natural history museum at the Maxbrücke .

The tracks of the Schweinfurt tram , which ran from 1895 to 1921 (see picture: Spitalstrasse and Schultesstrasse ) were later laid along the middle variant, but the southern variant was implemented in 1852, between the first-built city station east of the old town and the shunting station built in 1874 and central train station in the west. The siding for the port facilities was decisive for this variant.

On the one hand, this cut off the old town from the banks of the Main; on the other hand, it brought enormous advantages. The city was left with unsightly, larger railway areas in the city center, as in many other cities, because the main passenger, freight and marshalling yard with later depot was built far outside, 2 km west of the old town, in the area of the municipality of Oberndorf . There was then enough space to build up large-scale industry. This formed the basis for an exceptionally well-ordered urban development from the 1930s to the present day, with a large, but also compact industrial, railway, power station and port zone in one place. Otherwise, as in many other industrial and large cities, such as B. Nuremberg , these areas scattered between residential areas, would divide the city, with an unattractive overall picture.

In the 1960s, a freight train derailed in the Harmonietunnel . Around 1970 the line was electrified , except for the tunnel, which was too low for this. Trains with electric locomotives had to roll through the tunnel without power, which was therefore demolished a short time later and replaced by a trough with a cover in the middle area. In 2009 the regional train stop Schweinfurt-Mitte was opened on the western edge of the old town within the S-Bahn- like route along the city center. Another stop at the Fischerrain , as a connection to the central bus station, was previously considered, but has not been implemented until today (2017).

More than 100 years after the construction of the railway came the next major transport project that essentially gave the banks of the Main along the old town its current shape, the construction of the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal in the early 1960s.

Founding period

Today there are only a few business buildings in the Wilhelminian style left in the old town , like some bank buildings. In addition, the Holy Spirit Church , which was built in the course of industrialization for the Catholic rural population in the Protestant, former imperial city in place of a sugar factory from 1897 to 1902.

Holy Spirit Church

Schultesstr.

(1902)Bayerische Staatsbank Schultesstrasse

today the office building

(1908)

World War II and post-war period

The old town was 40% destroyed in World War II (see article introduction) in contrast to neighboring Würzburg , which was 80% destroyed by a firestorm that did not take place in Schweinfurt. The city was destroyed by about 45% on average and thus just as badly as Rothenburg ob der Tauber .

A planned reconstruction of the city in the 1950s and 1960s was only necessary in a few places, which meant that for a long time there were some vacant lots in the side streets of the old town, today (2019) still in Hadergasse. After 1945, as part of the reconstruction, a wide main street was planned across the old town, over largely destroyed areas, by relocating Zehntstraße, which was to connect from the northern market square across Manggasse to Neutorstraße. The major project was not implemented, also because of the continued use of the supply lines preserved in the ground.

In the old town, due to demolitions and bomb damage, there is a typical mixed development from many epochs for partially destroyed German cities. From the late Middle Ages to the early modern period, to the post-war period and modernity, around the Roßmarkt to urban chaos.

Schweinfurt model

In the 1970s, many smaller commercial and commercial enterprises were relocated from the old town backyards, some of which were destroyed in the war, to the new industrial area Hafen-Ost . This was the prerequisite for the subsequent renovation of the old town . This is made possible by the Schweinfurt model , which is being imitated nationwide. The city buys the "hopeless cases" in a redevelopment area, makes them attractive with property regulations, demolition of outbuildings, basic or partial renovations and verified usage suggestions and ensures a manageable risk when buying at moderate prices.

Although renovation of the old town is very difficult due to the often complicated ownership structure, diverse interests and unattractive properties, the city of Schweinfurt has achieved great success here. Since the old town renovation began in the old commercial district in the 1980s , one quarter after another in the eastern and central old town has been renovated across the board. In the end, a harmonious, historical overall picture emerged in the individual quarters, although in some places there was little historical building fabric left. As a result, this area of the old town has since acquired an increasingly historical character. Gaps in construction were closed neither in retro style nor with modern contrasts, but in a sensitive way. Currently (2019) the old town is being renovated in the quarter between the Zeughaus and Kornmarkt (see: City expansion around Bauerngasse ). The last to follow is the Keßlergasse / Zehntstrasse district (see: Keßlergasse / Lange Zehntstrasse ).

The western part of the old town lies outside the redevelopment areas and has largely lost its old town character. It developed into a modern city area with business and department stores, for example the Jägersbrunnen in the post-war period and more recently Georg-Wichtermann-Platz (see: Jägersbrunnen and Georg-Wichtermann-Platz ).

population

Population development

| date | Residents old town |

|---|---|

| 1800 | 6,045 1 |

| December 1, 1840 | 7,766 2 |

| 1868 | 9,748 3 |

| December 1, 1871 | 10,840 2 |

| December 31, 2015 | 2,529 1 |

|

1 Information about the city of Schweinfurt

3Information in Back then in Schweinfurt. P. 8

|

|

When the empire was founded in 1871, the old town, which at that time was essentially only surrounded by smaller factories and industrialist mansions, had around 10,000 inhabitants, which corresponds to a population density of 25,000 inhabitants per square kilometer. Until then, the population of the old town was almost identical to that of the whole city. In the first decades after the Second World War , around 5,000 people lived in the old town on an area of 0.4 km², as many as then, for example, in the City of London (1951: 5,324 inhabitants on an area of 2.9 km²). In 2015 the old town had only 2,500 inhabitants, while in comparison the only slightly larger old town of Frankfurt am Main (0.48 km²) had 3,937 people.

Social structure

| Status December 31, 2015 |

Old Town (District 11) |

The entire Schweinfurt area |

|---|---|---|

| German | 74.4% | 70.7% |

| Dual nationals | 6.9% | 16.1% |

| Foreigners | 17.7% | 13.2% |

The population structure of the old town reflects the post-war history of the district. The relatively few apartments in the area dominated by commercial buildings were mostly of a very low standard in the post-war decades. The long-established bourgeoisie had almost completely left the old town and the proportion of foreigners rose sharply as a result of cheap living space. Since the renovation of the old town, which began in the 1980s, this area got a completely different character, with attractive old town apartments. Germans moved in again, but for late repatriates (mostly dual nationals ) who also came to the city in the 1980s, the refurbished living space in the old town was usually too expensive. This explains the apparent contradiction among migrants , with a disproportionate proportion of foreigners and a disproportionate proportion of dual nationals.

places

Inner old town

Main bridge and bridge gate

Until the end of the 14th century , traffic across the Main near Schweinfurt was only possible by ferry. Only a privilege granted by King Wenceslas in 1397 allowed the city to build bridges, mills and hydraulic structures of all kinds on the Main, and the city was allowed to impose a tariff to cover the construction costs. The bridge was built by 1408 at the latest, where damage from ice drift was reported. And that, in connection with floods, remained the big issue into the 20th century . On the northern side of the Main, on the city wall , the bridge gate, which was demolished in 1833, was built, a double gate. The Leopoldina was founded in the Zwinger des Brückentor after a copper engraving from the 19th century . In 1652 the oldest permanent science academy in the world, the Leopoldina , today's National Academy of Sciences, was founded in Schweinfurt , before the corresponding societies in Paris and London . Today's Maxbrücke is already the seventh bridge at this point and meanwhile the third road bridge over the Main. In the 2020s it will be demolished and replaced by a larger new building.

Brueckenstrasse

The entrance to the old town at Maxbrücke became the city's new landmark. The branch of the Bavarian State Social Court (2000), the Georg Schäfer Museum (2000), the main customs office (2007) and the city library (2007) in the expanded medieval Ebracher Hof are “the most beautiful entrée” (from west to east) . It shows "how tradition and modernity [...] unite in the most excellent way."

The Georg Schäfer Museum (MGS) (1998–2000) by Volker Staab was opened in 2000 and received two architecture prizes. The entire ground floor is accessible with free entry and is designed as an agora , a public meeting point with a café, museum bookstore and large staircase between the main loggia and the town hall loggia , in which the two main entrances are protected by large open stairs and a ramp. In the exhibition rooms on the upper floors, the surroundings were also included through visual axes to the old town and the Main.

The city library (2004–2007) by Bruno-Fioretti-Marquez opposite the MGS is a conversion and expansion of the Ebracher Hof. With a new underground base floor and the so-called lantern as a skylight , a 33 meter long glass bar that follows the course of the former city wall and forms the framework for a small piazza . The main customs office (2005–2007) is also by Bruno-Fioretti-Marquez and completes the building ensemble , which in 2008 was named one of the 24 best buildings in Germany by the German Architecture Museum in Frankfurt .

On the way to the market square you pass the monument of Olympia Fulvia Morata (1526 to 1555), a poet and humanist scholar from Ferrara who is closely connected to the history of the city of Schweinfurt. In the second city ruin ( see: City foundation ) she lost all her belongings, could only save her bare life and died a short time later at the age of only 30.

- Brueckenstrasse

City library (2007)

in the Ebracher Hof (1578)Georg Schäfer Museum (MGS)

market

In the middle of the eastern old town, at a historic intersection (Rathauskreuzung) , is the market (main market). Here the old road crossed along the Main line from Bamberg in the direction of Frankfurt am Main with the north-south connection from Erfurt over the Main Bridge to the southern region. The market probably only came into being at the end of the 13th century , is first mentioned in documents in 1336 and is therefore not as old as the neighboring district of Zurich . Apart from the town hall, there are no significant historical buildings on the market. However, the large square with the triad town hall, Rückert monument and the line of sight to St. Johannis is proportionally balanced and has retained its overall historical character.

The old town hall (1570–1572) by Nikolaus Hofmann from Halle (Saale) is considered a brilliant achievement of the profane German Renaissance . On the evening of April 20, 1959, the roof of the Old Town Hall, which had survived the Second World War unscathed, was on fire. The east gable curved outwards and threatened to fall into Brückenstrasse. However, the fire brigades brought the fire, which was probably triggered by welding work, under control. In the 1980s, the large vaulted cellars were restored and the Ratskeller opened (today Aposto ).

Next to it the New Town Hall (1954–1958) by Fred Angerer , which has now also been placed under monument protection. The large inner courtyard with a fountain is now part of a publicly accessible sequence of courtyards, squares, arcades, open staircases and loggias , from Martin-Luther-Platz via the market to the staircase of the Georg Schäfer Museum .

The poet Friedrich Rückert was born in 1788 in Markt 2 (Rückerthaus) , diagonally across from the town hall (Markt 1). He was also a pioneering translator of oriental poetry, spoke at least 44 languages and was the first to translate parts of the Koran into German. Rückert was Germany's most popular poet in the 19th century, had a distant relationship with the bon vivant Goethe and was forgotten in the 20th century. The Rückert monument (1890) on the market square is a bronze cast by Wilhelm von Rümann and Friedrich von Thiersch . At the feet of the poet sitting on a chair there are allegorical figures from his works The Armored Sonnets , which he wrote in 1813 under the pseudonym Freimund Raimar against Napoleon I and the wisdom of the Brahmin .

Several well-known personalities stayed at the market, especially in the brewery (No. 30; see: lower middle picture)

- “ King Gustav Adolph of Sweden lived in house no. 8 on October 20, 1631, and in house no. 30 there in 1625 Wallenstein., 1634 Octavio Piccolomini, 1813, as a plaque in the upper forecourt says, Emperor Alexander of Russia his triumphal march to France, and in the 1830s King Ludwig I of Bavaria twice. "

During the Second World War , the southern half of the west side of the market was almost completely destroyed. The reconstruction of this row of houses is a successful example of town houses from the early 1950s. A planned reconstruction was not necessary on the less damaged east side and it formed an ugly torso for a long time. The Kaufhof AG (formerly Tietz ), which had opened a department store in the city in 1884 (see: Spitalstraße ), here thought to build a department store before Horten on Jägersbrunnen opened 1964th

- market

Market south side of the

old town hall , the new town hall

and the Rückert monumentMarket north side

around 1891

with St. Johannis and Brauerei-Gasthof Brauhaus (right)

Martin-Luther-Platz

Not far north of the market, a flight of stairs leads up to Martin-Luther-Platz, historically the best preserved square in the city. In the cadastral plan of 1868 the square is called the churchyard .

On the square is the Johanniskirche (from 1200, Romanesque , Gothic and other architectural styles), the main Protestant church of the city and the oldest surviving building in Schweinfurt, which was first mentioned in writing in 1237. The construction of a three-aisled basilica began around 1200 . In 1237 the north tower with the Romanesque tower chapel was completed, the south tower was dispensed with. The church has been Protestant since 1542, one of the most important ecclesiastical monuments between Bamberg and Würzburg . St. Johannis was planned as a civic church, but from 1325 the council of the city of Schweinfurt had to carry the construction load. Almost all European architectural styles over 8 centuries, from Romanesque to Classicism, are represented. The old grammar school (1582–1583, Renaissance ) behind St. Johannis has been home to the City History Museum since 1890. It is currently (2017) being expanded and will therefore remain closed until at least 2019. [obsolete] In Wenkheimer Gässchen there was a farm of the Franconian knight family von Wenkheim (also: von Wenckheim ), which the city bought in 1445. In 1503 an imperial bailiwick was established there. The Wenkheimers later owned large estates and castles in Hungary and appointed a prime minister.

The Kulturforum Martin-Luther-Platz is to be built by 2021, by connecting the old grammar school with the city history museum, the city clerk's house, the old Reichsvogtei and a commercial building on Oberen Straße. The city archive from the neighboring Friedrich-Rückert-Bau and the Otto Schäfer Collection , which will be donated to the city as a donation together with the museum building on Kiliansberg , will also find a new home here. Then the Friedrich-Rückert-Bau from the 1960s, the renovation of which would cost an estimated 7 to 8 million euros, is to be demolished and space is to be created for an underground car park on which apartments are to be built. The aim is to further develop Martin-Luther-Platz, together with the Gunnar-Wester-Haus , which has remained unchanged , into a museum district.

Spitalstrasse

|

|

|

|

Spitalstrasse after 1894,

with horse-drawn tram , looking east |

Spitalstraße 2017,

view in the opposite direction |

During the National Socialist era , Spitalstrasse was renamed Adolf-Hitler-Strasse . The Spitalstrasse, which leads from the market to the west, was the undisputed main street and the main business center of the city until the 1960s, when the westward shift of the city area began. In 1982 Spitalstrasse became a pedestrian zone.

In the cadastral plan of 1868, Spitalstrasse, Steinweg and Schultesstrasse already formed an 800 long western main development axis of the city, which apart from here had hardly grown beyond the city wall. It was not until six years later that the Centralbahnhof and later the main train station opened a kilometer further west . The first municipal tram in Bavaria, the Schweinfurt tram , ran on this western axis from 1895 to 1921 as a single-track horse - drawn tram to the main train station. The tram depot was at the Mühltor, which was demolished in 1876 .

In 1884 Leonhard Tietz from Stralsund , the founder of today's department store chain Kaufhof , opened his second branch in Schweinfurt, which he passed on within his family in 1893. The former Tietz department store in Schweinfurt gave way to a new building with Commerzbank. Spitalstrasse and Steinweg (see: Schultesstrasse ) became a boulevard and a promenade for the bourgeoisie around 1900 . With (from east to west) the Café Viktoria , the Mode Bazar Louis Voit , the Café Restaurant Metropol , the Tietz department store , the commercial hall , the Heilig-Geist-Kirche , the Steinwegschule and the Königliche Filialbank , which later became the Bavarian State Bank.

Rückertstrasse

Rückertstrasse was once called Mühlgasse , which led to the Mühltor , which was demolished in 1876 . It was renamed after Friedrich Rückert , who was born in the corner house on the market (see: market ). This is where the town hall intersection was located , which is now meaningless (largely a pedestrian zone). Since 1950 at the latest, the first traffic lights in the city have been regulating traffic here, by means of a glass pulpit on the first floor of the Rückerthaus, in which a police officer switched the system by hand as required.

Until the post-war period, a tram track ran through Rückertstrasse, as a relic of the Schweinfurt tram that ran until 1921 and which is still reminiscent of the Zur Straßenbahn restaurant on Rückertstrasse .

Rückertstrasse was one of the city's most important shopping streets until the early 1960s. Until then, for decades, the main business center was shifted and expanded to the west, finally far beyond the old town limits, with the opening of the Stadtgalerie Schweinfurt in 2009. The opening of the Rückert Center in the early 1970s, at the end of Rückertstrasse, directly behind the city wall , did not bring the hoped-for revitalization of the street. In the 1990s, Rückertstrasse experienced a brief second boom as a chic shopping street, then several business closings again, while in more recent times it has reappeared in a better picture.

- Rückertstrasse

Mühltor (1564), on the right

Café Beier (aborted 1991)

before 1876

Zurich

The Zürch is a former castle district and is generally regarded as the oldest quarter of today's old town, although that is not certain. The more than 300 year old Zurich fair is the oldest fair in Lower Franconia . The quarter has narrow, paved streets on a medieval town plan, with some very small houses and is surrounded by the almost completely preserved town wall. Through all of this, Zurich has retained the character of a castle district to this day, despite the castle that has not existed for 600 years.

Former commercial district

The former commercial district includes Juden-, Peters-, Rosen-, Nuss- and Metzgergasse. It was once delimited by three city gates as corner points: the bridge gate in the east, the Fischertor in the south and the inner hospital gate in the west. The town hall quarter in the north is no longer part of the former commercial district. The renovation of the old town of Schweinfurt began in 1979 in the old commercial district, as the redevelopment area Old Town 1: Southern Old Town (3.9 hectares). The former commercial district is registered as a building ensemble in the Bavarian list of monuments.

In 1986 the alleys were redesigned to become a traffic-calmed area , using paving stones to preserve the historic alley character.

The quarter lies behind the former Great Main Mill , which served various branches of industry and of which large successor buildings (spinning mill) have been preserved. In addition, the quarter was behind the former Main Harbor, which is now 1.5 km down the Main on the opposite (southern) side of the Main in the industrial area Hafen-West . The former commercial district with its landmark, a scrap tower , is a closed urban area with a medieval street plan and two-story, mostly eaves-side buildings, with facades from the 18th and 19th centuries and formerly commercially used rear buildings.

In the late Middle Ages, the first synagogue of the Jewish community of Schweinfurt stood in Judengasse, in place of today's Friederike-Schäfer-Heim of the Schweinfurt Hospital Foundation . The new building of the old people's home from the 1950s divides Petersgasse into two parts, the part on the Main is now called Nussgasse . In 2018 it was decided to tear down the home and replace it with a new building elsewhere.

The scrap tower was built by Balthasar Rüffer III in 1611 as a representative stair tower for a four- story , two-winged Renaissance house . built. From 1818 until 1908 the building was used to manufacture shotgun pellets . The Welsh hood of the tower was therefore torn off and this was raised by four floors and a shot trap with a melting pot was installed. The north wing was destroyed in the last war. In 1985 the city bought the tower and the south wing, which was threatened with decay, removed roof structures from there and renovated the complex until 1990. The cabaret, the scrap tower cellar, is located in it . Otherwise there was no building substance worth preserving around the tower and south wing. That is why the rest of the area was completely cleared and then narrowly and carefully built up again. The entire area appears today as a closed old town quarter. In place of the northern wing, a new building of the same size was built by a private client until 1991, with an art gallery and studio. Thus the two wings again form the former courtyard on Petersgasse.

Petersgasse 6 and 8 were the main buildings of the Kugelfischer company . The courtyard complex at Metzgergasse 16 was probably built in 1594 in post-Gothic forms and is a very well-preserved courtyard from the 16th century . The former mayor of Würzburg , the merchant Balthasar Rüffer, lived in it .

As a result of the renovation of the old town and the Georg Schäfer Museum , which was opened in 2000 , the quarter was greatly upgraded and, with several bars and restaurants, became a meeting place for the urban bourgeoisie.

- Former commercial district

Metzgergasse 16 courtyard on the banks of the Main

Keßlergasse, Long Zehntstrasse

|

|

|

|

Zehntstrasse with baroque house ...

|

... and the Twelve Apostles

|

The redevelopment area Altstadt 5: Keßlergasse, Lange Zehntstrasse (4.0 ha) is one of the oldest pedestrian zones in Germany, in which Keßlergasse is only 3.50 meters wide at its narrowest point. The name Zehntgasse (today's Zehntstrasse) can be traced back to 1424 and goes back to the Zehnthof of the Haugs Abbey in Würzburg , built in 1387 . Today there is the post office in the city center and not far to the west is the Twelve Apostle House . In the cadastral plan of 1868, the fields outside the city wall closest to here still bear the field name tithe .

From the 1980s to around 2010 there was a market hall with retailers and restaurants between Keßlergasse and Langen Zehntstraße. At that time in particular, the quarter had a southern flair. In 2018, a larger district development with the Krönlein-Karree (also: City-Karree ) between Keßlergasse and the post office was completed (see picture: Georg-Wichtermann-Platz ).

Inner and outer old town

Krumme Gasse, Am Oberen Wall

The area around Krumme Gasse and along the Upper Wall is located on the northeastern edge of the old town and in its northern area is already in the area of urban expansion. It corresponds to the redevelopment area Altstadt 3: Krumme Gasse, Am Oberen Wall (7.9 ha) and was largely redeveloped in the 1990s. The Krumme Gasse is registered as a building ensemble in the Bavarian list of monuments.

The narrow area stretches 400 meters along the largely preserved or partially reconstructed city wall and in its northern area lies steeply above the valley of the Marienbach . With its narrow, winding, but not connected alleys, it does not form a closed quarter. This old town area borders on Rückertstrasse in the south. In the west it is bounded by the market and the Oberen Strasse (formerly: Obere Gasse or Obertorgasse ), which was once in the main business center of the city, until a shift to the west began (see: Rückertstrasse ).

The Krumme Gasse was mentioned as a cobbled street as early as 1434. During the renovation, the streets were paved for the first time only at the edge and provided with a band of structured asphalt in the middle to make them easier to walk on and drive on.

The main guard was in the middle of the area above the city wall. In a plan from 1771 it is shown on the roof with three cannons pointing towards Kiliansberg . The Roth brewery, which has been in existence since 1818, is now located in the place of the Hauptwache, in some historic buildings. The Roth'sche Haus (also: Schopperhaus ) from 1588 at Oberen Straße 24 was a larger Renaissance building that was hit by an explosive device in 1944 and destroyed the house, with the exception of the well-preserved ground floor, which has always been a restaurant is located. A mysterious inscription in the courtyard entrance of the house reports on the alleged meteorite fall from Schweinfurt on the property in 1627, which cannot be proven.

This old town area borders in the north on the Motherwell Park , part of the ring system around the old town, on the Obertotschanze, which is still preserved or restored, with the velvet tower.

- “ The history of the Velvet Tower, which has been expanded and converted many times, has not been fully explored. What has been clarified, however, is the origin of the name, which has nothing to do with fabrics and nothing to do with the built-in sandstone, but rather comes from French. Le Sommet is the name of the summit and stands for the highest point of the city fortifications. "

- Krumme Gasse / Am Oberen Wall

For more pictures see: Schweinfurt model

Georg-Wichtermann-Platz

The former meat bank on the square of the same name was demolished in 1890. The post office was relocated here from the Stadtbahnhof and the square was renamed Postplatz . In 2005 the place was renamed again. Since then, he has been named in honor of the long-time mayor Georg Wichtermann (1956 to 1974). Due to the lack of historical reference, the renaming has recently been negated by nearby shops in favor of the name Alter Postplatz .

The square is located between the inner old town in the east and the urban expansion in the west, which is now a modern city area in many places. The square no longer has the character of an old town and is therefore not part of the old town redevelopment areas. The inner city moat ran through today's square until 1437 (see: City expansion ), which was encountered under this square when the two-story underground car park was built in 1986. Bread and meat banks for bakers and butchers have been located here since 1562. From 1804 to 1890 the meat bank building stood here in the middle of the square . On the cadastral plan from 1868, the place is therefore also referred to as the meat bank . After that, the city post office was built on the same site, which in 1893 already had 40 telephone intercoms, the place was henceforth called Postplatz . In 1966 the post office was demolished. After the construction of the underground car park, the space above was planted with plane trees from Italy and designed as a sandpit for boules based on the Mediterranean model , which not all citizens understood and demanded a sealed area.

- A place through the ages

Outer old town

Fischerrain

The Fischerrain occupies a special position. It does not belong to the area of the structural expansion of the city, but is nevertheless located directly outside the first, former wall ring, with the (inner) city gates. The small quarter on the Main was originally an independent fishing settlement. It is not known when it was integrated into the old town, whether before or in the course of the city expansion from 1437 and whether it existed before the city of Schweinfurt was founded. After being incorporated into the expanded city fortifications, the quarter had its own access to the city for the fishermen, the Fischerpforte .

The quarter, which once had numerous fish shops, breweries, inns and restaurants, has largely retained its typical Franconian character away from the main thoroughfare. Today there are still two fish shops and two restaurants, the Hess wine restaurant, the successor to the traditional Gößwein wine bar .

Kornmarkt, Bauerngasse, Armory

The redevelopment area Altstadt 4: Neue Gasse, Zeughaus (9.5 ha) has been redeveloped since the 2010s. It covers the northern old town (former name: Am Oberen Anger ) between the two former marketplaces Getreidemarkt (today: Kornmarkt ) and Schweinmarkt (today: Am Zeughaus ).

The Kornmarkt was dominated by the Obertor until it was demolished in 1872. The northern old town is located in the area of the first city expansion, as indicated by the street names Neue Gasse and Graben (inner ditch). The name The village in the city for the self-contained, small-scale district of Zurich is more appropriate for the northern old town, as the name Bauerngasse indicates. This quarter was on the edge of the largest agricultural area in the imperial city area, which the city acquired from the Teutonic Order . The residents come mainly from the village of Hilpersdorf , which was located in the imperial city area south of the Bellevue and became a desert because the imperial city council asked the residents to move into the city. They did not settle until after 1437 at the earliest at the Oberen Anger , popularly known as the Bauerngasse . This name can only be traced back to 1809. The houses on the city wall in Neue Gasse lay on striped corridors that stretched far beyond the city fortifications. Wine was also grown here and wine taverns emerged, such as the traditional Hammer wine tavern, which closed in 2013 .

The Armory (1589 - 1591) was arsenal of imperial city and was extensively restored in 2014 and transformed the space. The central fire station with a large hose drying tower stood on it until the Second World War. At the Zeughaus, in the Bauerngasse and at the Kornmarkt there have been numerous inns from historical times until today. In this pub mile, which flourished in the 1990s with additional new music venues, the now internationally known idea of the Honky Tonk pub festival was born in 1993 (see also: Schweinfurt, Nightlife ).

The historic cityscape in this area was not only disturbed by bomb damage, but also afterwards until the 1970s by faceless new buildings and shop conversions. The old town has been renovated here since the end of the 2010s (see also: Schweinfurt model ).

- Kornmarkt / armory

Kornmarkt north side

with Obertor

(demolished in 1872) to the

left of the SattlervillaArmory (1591)

There were once two breweries in the quarter. The Schweinfurt Am Graben club brewery founded in 1845 and the Wagnerbräu Am Zeughaus founded in 1870 (see also: List of former breweries in Bavaria, Schweinfurt ).

To the north, the area borders on Fichtel's garden in the former ski jumping facility, where the sophisticated Fichtelsvilla, which was destroyed in the last war and only the stairs remained. For the park, Mies van der Rohe made an unrealized design for the Georg Schäfer Museum , which was then realized in an enlarged form with the New National Gallery in Berlin .

Rossmarkt

The western old town around the Roßmarkt is, like the northern old town, in the area of the first city expansion (see: City expansion ) . The Bürgerhof with its Renaissance gable (today the Sparkasse) is still preserved from the Schranne on Roßmarkt . The Schranne was once a large complex with a garden courtyard together with the municipal brewery, the communal brewery . The Bauschenturm from 1615 is a Renaissance stair tower for the Bauschhaus . With an inscription on the Leopoldina , today's National Academy of Sciences , which, however, was not founded in the Bauschenhaus , as was once assumed , but in the office of the city physician Johann Laurentius Bausch , in the Zwinger of the bridge gate . The medical officer is said to have used the tower as an observatory . In the Thirty Years' War who lived here Field Marshall of the Swedish army Karl Gustav Wrangel . The Bauschenhaus was a castle-like house on Roßmarkt that was rebuilt and extended in the neo-renaissance style in 1876 and still exists today in the western part of the outer walls.

Today's Roßmarkt represents urban chaos, with a mix of small, historic old town houses through to large, new commercial buildings. In the early 1960s, the city bus station was relocated from the market to the Roßmarkt and redesigned in 1997. Since then it has been spanned by a star-shaped glass roof.

Wolfsgasse, Hadergasse

The quarter between Wolfsgasse and the city wall was once a quarter of poorer people, which can be seen in historical photos and also in the cadastral plan from 1868, with relatively disorganized, small-scale development and larger gaps. Here is Hadergasse, with the prison nicknamed Villa Rosa , named after the red paint on the building, which was retained during the renovations in 2003 and 2006 because of the nickname. The city wall serves as a prison wall here.

The legendary, now closed, music pub Shepherd's opened in Hadergasse in 1969 . It was part of a smaller pub mile (on the west side of the alley; lodge , among others ). On the east side is the last larger, not yet closed war construction gap in the old town. Around 2015, the Neue Hadergasse quarter on the city wall was completed, on an open space of the large Lebküchner wine shop that was destroyed in the war , with a Renaissance house.

Hunter's well

The Jägersbrunnen was called An der Scheuer in 1599 and previously next to the Judenkirchhof , as there was a Jewish cemetery there until 1554. The fortifications of the Schweinfurt city wall ran across the western area of today's Jägersbrunnen . The three-story market hall on the north side, which was destroyed in the last war, was completed by 1898 at the latest. On the south side stood the Barthelsvilla, which was damaged in the war.

The Jägersbrunnen no longer has the character of an old town, but has developed into a metropolitan area. In the early 1960s, Horten AG acquired the large ruins of the former German gelatine factory outside the old town . Since the city of Schweinfurt did not want a department store there outside the city area, it swapped this area with Horten AG for the ruins of the Barthelsvilla at Jägersbrunnen. For the construction of the department store (today: Galeria Kaufhof ), which opened here in 1964, a city wall tower was demolished against protests, some of which only consisted of a replica from the 19th century. The originally planned four-storey department store with hydrangea tiles allowed the city to build only three storeys, taking into account the neo-baroque Palace of Justice opposite, which, together with the department store and other buildings, is considered a successful architectural ensemble . Germany's third largest video advertising wall is located at the Iduna high-rise .

Hohe Brückengasse

The west side of Hohen Brückengasse is a successful reconstruction example of a commercial building front from the early 1960s.

Siebenbrückleinsgasse

Siebenbrückleinsgasse runs south of the Roßmarkt. Before a stream flowed from the former Spitalsee (see: city center, Spitalseeplatz ) through the city ditch into the Main at the Spitaltor, it turned eastward in front of it and flowed through Siebenbrückleinsgasse. Then he turned south again and ran along the northern section of today's Fischerrain road into the Main through the inner ditch. This separated the original old town from the old Fischerrain fishing district , which was included in the city fortifications when the city was expanded. In Siebenbrückleinsgasse, after the first, medieval synagogue in Judengasse (see: Old Industrial Quarter ), the Jewish community center of the second Jewish community in Schweinfurt was located .

Schultesstrasse

In the Wilhelminian era , the Schultesstrasse, which adjoins Spitalstrasse to the west, was called Steinweg and its continuation outside the city wall and Spitaltor was called Schultesstrasse . Today the Steinweg is called Schultesstraße and the former Schultesstraße is called Gunnar-Wester-Straße . Today's Spitalstrasse (previously: Spitalgasse ) led to the Spitaltor. This is where the Hospital of the Holy Spirit , which has been occupied since 1364, was destroyed in the Second Margrave War in 1554 and rebuilt around 1600, and the associated hospital church were located . From the building complex demolished in 1896, a farm building from 1612 has been preserved, with a late Gothic core from 1364. It is hidden behind the Holy Spirit Church, which was built in 1912 and named after the hospital .

Steinweg with Inner Spitalturm (left, demolished in 1870), Spital zum Heiligen Geist (center) and Spitalkirche (right)

Spital (left) and Holy Spirit Church

See also: Founding period until the 1920s

City gates

The five Schweinfurt city gates were all demolished in the second half of the 19th century . The bridge gate was at the old Main Bridge as the southern entrance to the city. Then followed (counterclockwise) Mühltor , Obertor , Spitaltor and Fischertor as a special access for fishermen, which was not far west of the bridge gate and closed the circle. In total, with inner and outer gates, eight city gates were built in the course of time: Brückentor , Mühltor , Inner and Outer Upper Gate , Inner , Middle and Outer Hospital Gate and Fischertor . There were also small front and side gates, such as the Zwingertor and the Gerberstieglein at the bridge gate , which also consisted of two gate towers as a double gate.

In addition, there were other gates, such as the field gate, on the local wall of Oberndorf, which was part of the imperial city .

City wall and ring systems

The Schweinfurt city wall was first mentioned in a document in 1258. The southeast corner of the city wall in what is probably the oldest quarter of the old town of Zurich was also the enclosure wall of the Reichsburg, which was located here from 1310 to 1427. Here are two defense towers; one of them is the Türmle wine tavern . Bastions have been preserved or partially reconstructed in the northeast. The north-east corner is marked by the velvet tower , once also the detention tower. In the second half of the 16th century , the eastern wall (today: Am Unteren- and Am Oberen Wall ) was raised significantly, as the eastern side was viewed as the most dangerous attack side, as a shelling on the city was possible from Kiliansberg . That is why the Mühltor was rebuilt here in a more massive form after the Second City Ruin (see: Schweinfurt, Early Modern Times ) in 1564. In the 1640s, in the course of the Thirty Years' War , which the city survived unscathed, the outdated, medieval city wall was expanded into a modern fortification with entrenchments by Field Marshal of the Swedish Army and statesman Karl Gustav Wrangel , who had his headquarters on Roßmarkt .

Since the 1990s, discoveries have been made on the city wall again and again as a result of difficult access and construction work. For example, with the Jungfernkuss discovered in 2007 , a shell tower that comes in part from a Carmelite monastery founded in 1367 (until 1542). Parts of the Spitaltorbrücke from 1748 were rediscovered and exposed during construction work in the late 1990s. In 2016, the small Höpperle tower on the western city wall , which was destroyed in the Second World War, was reconstructed.

Around the old town with the partially preserved city wall, with short breaks, there are ring systems. Starting from the north, in a clockwise direction, the following parks form a green band:

- Fichtel's garden , in front of the northern city wall . With a flight of stairs as a remnant of Karl Fichtel's large villa that was destroyed in the last war .

- Motherwell Park , in front of the north-eastern city wall, named after the Scottish twin town Motherwell .

- Philosophers walk / Am Oberen Wall , park in front of the eastern city wall, with pond and fountain, at the Marienthal house .

- On the Unteren Wall , in front of the eastern city wall and St. Salvator , in the former Zurich castle district .

- Bastei , city beach in an old main bastion at the mouth of the Marienbach and opposite the Böckleinsinsel . Not far from there, at the Zollhof, is a landing stage for river cruise ships .

- Gutermann promenade with green space along the Main , west of the Maxbrücke and opposite the Main Island Bleichrasen . The promenade leads past (industrial) monuments, the spinning mill, the cultural center Disharmonie with terrace café, the beer garden at Mole 9 , the old fishing district Fischerrain , the Schweinfurt run-of-river power station and the Schweinfurt Mitte DB stop .

- Old cemetery , in place of the cloister garden of the Carmelite monastery (see above) not far from today's Heilig-Geist-Kirche .

- Schillerplatz (former theater location) with inset words by Friedrich Schiller and a fountain, in front of the New Baroque Palace of Justice.

- Green area and forecourt at the arcade building of the Kunsthalle Schweinfurt , with the Rossbändiger fountain .

- Châteaudun Park , in front of the north-western city wall, named after the French twin town of Châteaudun . The theater of the city of Schweinfurt is located here .

There are numerous fountains and (industrial) monuments along the ramparts and Main Promenades (see: Monuments and fountains in Schweinfurt ).

See also

literature

- Edgar Lösch: Schweinfurt old town - history destruction renewal. Documentation on the renovation of the old town , ISBN 3-926879-36-X

- Edgar Lösch: History of the old inns in Schweinfurt . Schweinfurt Museumsschriften, Schweinfurt 2010, ISBN 978-3-936042-58-0

- Hubert Gutermann: Alt Schweinfurt - in pictures, customs and legends . Schweinfurter Tagblatt, Schweinfurt 1991, ISBN 978-3-925232-09-1

- Paul Ultsch: Back then in Schweinfurt. When the city wall was still a boundary . Book and idea publishing company, Schweinfurt, ISBN 3-9800480-1-2

- Erich Schneider : Schweinfurt and its monuments - architecture-art-technology . Verlagshaus Weppert, Schweinfurt 2015, ISBN 978-3-9803695-9-6

- Uwe Müller: Schweinfurt - over 200 views from the beginnings of photography up to the fifties . Sutton Verlag, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-89702-020-7

- Herbert Hertel: Schweinfurt in old views . European Library, 1996, ISBN 978-9028862258

- Bruno Erhard: Schweinfurt, yesterday and today - in 55 pairs of historical and current photographs . Sutton Verlag, Munich 2019 (from May 22nd) ISBN 978-3-95400-962-6

Web links

Video

Individual evidence

- ^ Population register-based population

- ↑ Overview map of the districts. Retrieved December 23, 2016 .

- ↑ a b c Historical Lexicon of Bavaria. Retrieved February 4, 2017 .

- ↑ Schweinfurt city culture topics. Publication of the Schweinfurter Tagblatt for the Handelsblatt and DIE ZEIT, p. 4

- ↑ a b c d e swity.de/Vorbild Schweinfurt: Old town renovation against housing shortages. Retrieved May 22, 2019 .

- ^ BayernAtlas / Historical map of Schweinfurt. Retrieved July 9, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Peter Hofmann: Schweinfurt guide

- ^ A b Paul Ultsch: Back then in Schweinfurt . Book and idea publishing company, Schweinfurt, ISBN 3-9800480-1-2 , p. 10 ff.

- ↑ Historical Lexicon of Bavaria. Retrieved May 24, 2019 . The streets are not mentioned here, but were derived from the map (1260 / 70–1437) of the city before the expansion, with the first city wall drawn in.

- ↑ Peter Hofmann: schweinfurtfuehrer.de/Geschichte/1400–1500. Retrieved July 3, 2020 .

- ↑ Measured from the land register plan from 1868

- ^ Paul Ultsch: Back then in Schweinfurt . Book and idea publishing company, Schweinfurt, ISBN 3-9800480-1-2 , p. 89 ff.

- ↑ a b c d e f List of the architectural monuments in Schweinfurt

- ↑ Various authors: How long do we have to live in these fears? . Verlagshaus Weppert, Schweinfurt 1995, ISBN 3-926879-23-8 , p. 61, map with the degree of destruction of German cities

- ↑ Several authors: How much longer do we have to live in these fears? Verlagshaus Weppert, Schweinfurt 1995, ISBN 3-926879-23-8 , p. 103

- ↑ mainpost.de: The Schweinfurt Model, August 22, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d mainpost.de: Why the city is buying and selling empty houses, May 16, 2019. Accessed May 17, 2019 .

- ↑ a b 1868 Schweinfurt, which at that time was still almost identical to today's old town, had 9,748 inhabitants. Paul Ultsch: Back then in Schweinfurt. When the city wall was still a boundary. Book and idea publishing company, Schweinfurt, ISBN 3-9800480-1-2 , p. 8.

- ↑ Population register-based

- ^ Paul Ultsch: Back then in Schweinfurt . Book and idea publishing company, Schweinfurt, ISBN 3-9800480-1-2 , p. 40 ff.

- ↑ a b Schweinfurt City | Culture | Topics. Special edition of the Schweinfurter Tagblatt for the Handelsblatt and DIE ZEIT: The most beautiful entrée. P. 3, May 20, 2009.

- ^ Time Machine Architecture , Fourth Architecture Week of the Association of German Architects (BDA) in Schweinfurt 2008, p. 2.

- ^ BDA Prize Bavaria 2001 and Architecture Prize Concrete 2001

- ↑ TV-Touring Schweinfurt, January 30, 2016.

- ↑ Bertelsmann Universal Lexikon, Gütersloh 1989.

- ^ Paul Ultsch: Back then in Schweinfurt . Book and idea publishing company, Schweinfurt, ISBN 3-9800480-1-2 , p. 29 ff.

- ↑ a b c Schweinfurter Anzeiger: Mayor Sebastian Remelé: "Through the hoarding, Schweinfurt turned from a provincial to a big city" - birthday cake for a long company history . September 24, 2014

- ↑ a b c d Map of Schweinfurt, with sights and history. Tourist Information Schweinfurt 2009

- ↑ Schweinfurter Tagblatt: Planned: Kulturforum Martin-Luther-Platz , July 28, 2016

- ↑ a b c d mainpost.de: Scrap tower: 30 years ago there was a celebration in the old town, April 27, 2020. Accessed on April 28, 2020 .

- ↑ List of architectural monuments in Schweinfurt, Ensemble of the former industrial district : file number E-6-62-000-4

- ↑ Peter Hofmann: schweinfurtfuehrer.de/Sehenswerte/Metzgergasse No. 16. Accessed on May 22, 2019 .

- ↑ mainpost.de: Pavement and cellar under the Schweinfurter Zehntstrasse, August 7, 2019. Accessed August 7, 2019 .

- ↑ List of architectural monuments in Schweinfurt : file number E-6-62-000-5

- ↑ Peter Hofmann: schweinfurtfuehrer.de/Sehenswerte/Das Roth'sche Haus. Retrieved May 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Schweinfurt prison for high and wealthy gentlemen, November 28, 2019. Retrieved November 28, 2019 .

- ^ Paul Ultsch: Back then in Schweinfurt . Book and idea publishing company, Schweinfurt, ISBN 3-9800480-1-2 , p. 39

- ↑ Peter Hofmann: schweinfurtfuehrer.de/Alte Stadtansichten und Infos / Fichtelsgarten am Obertor. Retrieved January 26, 2017 .

- ↑ Illustration in: Peter Hofmann: Schweinfurtführer.de / Roßmarkt. Retrieved January 28, 2017

- ↑ Peter Hofmann: schweinfurtfuehrer.de/Sehensertes/Der Bauschenturm. Retrieved May 22, 2019 .

- ↑ a b mainpost.de: The legendary "Shepherd's": One sausage - three menus, November 5, 2010. Accessed June 20, 2019 .

- ↑ Caption with incorrect information: In 1615, it was not the hospital tower that was built, but the new hospital gate to the left, only visible with the spire

- ^ Peter Hofmann: schweinfurtfuehrer.de/Geschichte/1700-1800. Retrieved May 22, 2019 .