Main-Danube Canal

| Main-Danube Canal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Course of the Main-Danube Canal |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water code number | EN : 1386 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| shortcut | MDK | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| position | Germany Bavaria | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| length | 170.71 km | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Built | 1960 to 1992 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| class | Vb | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Beginning | Junction from the Main near Bamberg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| end | Confluence with the Danube near Kelheim | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Descent structures | 16 locks between Bamberg and Kelheim | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ports | Bamberg, Forchheim, Erlangen, Fürth, Nuremberg, Roth, Berching, Beilngries, Dietfurt an der Altmühl, Kelheim | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical precursors | Fossa Carolina, Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Used river | Regnitz, Altmuehl | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kilometrage | from Bamberg (km 0.07) to Kelheim (km 170.78) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ascent | In each case towards the Bachhausen lock | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Responsible WSD | Danube Waterways and Shipping Office MDK | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main-Danube Canal in the Regnitz valley near Eltersdorf , Hüttendorf in the background | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

course

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Main-Danube Canal ( MDK ) is an approximately 171-kilometer-long federal waterway in Bavaria that connects the Main near Bamberg with the Danube near Kelheim .

The canal was built between 1960 and 1992. With it, a continuous large shipping route (called the European Canal ) was created between the North Sea near Rotterdam and the Black Sea near Constanța ( Romania ), which runs over the Rhine , Main and Danube. This is why the canal is also known as the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal ( RMD Canal ). During the planning and construction period, the name Rhine-Main-Danube large shipping route was also common. Regionally, it is often simply called the New Canal to distinguish it from its predecessor, the Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal . The 17 km long apex that crosses the low mountain range Franconian Alb as the European main watershed Rhine-Danube is 406 m above sea level. NHN the highest point on the European waterway network.

As a freight transport route (especially for container transport), the RMD Canal is steadily declining, but it is increasingly becoming a magnet for tourists and river cruises. The channel channel, together with the Franconian Lake District, is also part of the Danube-Main crossing , which supplies the Regnitz and Main river , which is threatened by temporary drought, with water from the Danube and Altmühl .

course

The kilometer zero of the Main-Danube Canal is located at the confluence of the Regnitz in the Main (Main-km 384.07) near Bischberg in the district of Bamberg . Initially, the canal runs in the Regnitz river bed. Parallel to the canal, the left, western arm of the Regnitz also crosses the center of Bamberg. At 6.43 km, the canal separates temporarily from the natural course of the river. Between Neuses an der Regnitz (km 22.07) and Hausen bei Forchheim (km 32.01) the canal shares its bed with the Regnitz for the last time.

The Main-Danube Canal passes Erlangen and Fürth , before it crosses the Rednitz in a steel trough bridge and reaches the south-west of Nuremberg . In the Eibach district , it turns south to run temporarily parallel to the Rednitztal valley to the west. At Roth , the artificial waterway curves in a south-easterly direction. After the Hilpoltstein lock (km 99) and an altitude difference of 175.1 meters, the 17 km long apex of the Main-Danube Canal follows . The European main watershed Rhine-Danube becomes at 102 km and 406 m above sea level. NHN water level overcome. A sculpture called the apex posture indicates the course of the watershed there.

The Bachhausen lock that follows (km 116) in the municipality of Mühlhausen (Upper Palatinate) leads the Main-Danube Canal down again into the course of the Sulz through Berching to the south. North of Beilngries , the canal curves to the east. At Dietfurt an der Altmühl (canal km 136.6) it meets the Altmühl. Their bed was enlarged and ten old barrages were replaced by two new ones. The dam-regulated Altmühl forms the last 34.18 km of the canal. This flows into the Danube after 170.78 km at Kelheim (at Danube km 2411.54). The difference in height from the top posture to this point, which is overcome by locks, is 67.8 meters.

The journey coming from the Main is considered to be an ascent even in the apex position, i.e. up to the Bachhausen lock. The ascent from the Danube ends as such at the same lock.

story

prehistory

Carolina fossa

The construction of a connection for small boats between the Main and the Danube was tried , according to current theories, as early as 793 with the Fossa Carolina (also known as Karlsgraben ). Remains of the excavations initiated by Charlemagne between a left tributary of the Altmühl and the Swabian Rezat are still preserved in the vicinity of today's place Graben north of Treuchtlingen . The project is believed to have been completed, as indicated by 2013 excavations showing the canal continues north of the visible Carolina fossa. The canal consisted of several short sections at different levels; the small boats were probably pulled from one section to the next over short ramps. Regulation of the water level was also planned through a pond below the Nagelberg.

Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal

Only after the Thirty Years' War and, above all, with the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in Germany , there were concrete plans to overcome the watershed again. However, due to the Napoleonic Wars , the corresponding projects took a back seat for the time being. In the year of his accession to the throne in 1825, King Ludwig I of Bavaria had commissioned the royal building officer Heinrich Freiherr von Pechmann to draw up plans for a renewed attempt at such a ship connection. After ten years of construction, the Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal was opened in 1846 , a 172.4 km long waterway between Kelheim and Bamberg. The volume of transport on the Ludwig Canal reached its first low point as early as 1880. The main reasons for this were the narrow width of the canal and the progressive expansion of the railway network , which made the operation of the waterway increasingly unprofitable.

The Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal was still used to transport wood and stones. The little damage caused by World War II was quickly removed. In 1950 the canal was completely abandoned. From the 1960s onwards, entire sections were removed and built over. The federal motorway 73 (Frankenschnellweg) between Nuremberg and Forchheim runs largely on the route of the old canal. The route of today's Main-Danube Canal roughly corresponds to that of its historical predecessor. In Bamberg and in the Altmühltal , the routes of the old and new canals are identical. A 65 km long section between Beilngries and Nuremberg is still filled with water and largely preserved in its original state.

Planning of the European Canal Rhine-Main-Danube

The technical progress in the second half of the 19th century required an increased volume of transport. At the same time it became possible at this time to build larger and more economical ships that could compete with the railroad. These developments led to a concept for a Central European waterway network for large ships. In addition to the west-east connection (Rhine / Mittelland Canal / Elbe ), the planners already planned a north-south connection ( Werra-Main Canal / Main / Main-Danube Canal / Danube). On November 6th, 1892, 29 cities and municipalities, 13 chambers of commerce and other economic partnerships founded the Association for the Elevation of River and Canal Shipping in Bavaria , today the German Waterways and Shipping Association Rhein-Main-Donau eV (DWSV). The main objective was to work towards an efficient large shipping route between the Rhine, Main and Danube. In the 1890s, the association submitted several applications to the government of the Kingdom of Bavaria to “have a draft for a new Danube-Main waterway drawn up”, but these were rejected by the Chamber of Deputies .

Starting in 1899, the association created its own concept, which was published in 1903 as a memorandum on the technical design of a new Danube-Main waterway from Kelheim to Aschaffenburg . In addition to the expansion of the Main for ships up to 1000 tons deadweight, the ambitious project envisaged the construction of a modern waterway between the Main and Danube for ships up to 600 tons. The converted bed of the Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal was proposed for the planned Danube-Main Canal. A shortcut to the Main to the west (Fürth - Neustadt an der Aisch - Marktbreit ) was also under discussion from Nuremberg . Without this variant, the project would have required the construction of 19 locks and three ship lifts . Instead of using the Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal entirely, there was also a more western variant from the Danube to Nuremberg: ( Stepperg - Pappenheim - Roth - Nuremberg). In Treuchtlingen this would have coincided with the historic fossa Carolina.

In 1917 the Chamber of Deputies received a bill to secure the "drafting of a draft for the construction of a large shipping route between Aschaffenburg and Passau ". This time the canal should already be able to accommodate the 1200-tonne class Rhine ships that were common at the time. After the Main from Bamberg and the Danube from Kelheim to the imperial border had become Reichswasserstraße on April 1, 1921, the German Reich and the Free State of Bavaria signed a state treaty on June 13th, 1921 “to implement the plan for the Main-Danube waterway as soon as possible ". Rhein-Main-Donau AG (RMD-AG), based in Munich, was founded as the executive body on December 30, 1921 . The plan for the Rhine-Main-Danube major shipping route included the expansion of the Main from Aschaffenburg to Bamberg and the Danube from Ulm to the Austrian border and a canal connection between the two rivers. To finance the project, RMD-AG was granted the concession to use the hydropower plants on the Main, Danube, Lech , Altmühl and Regnitz.

Mindorf Line

The expansion work on the Main and Danube could begin in the following years. Concrete plans for the canal between the two rivers did not come into being until the Rhine-Main-Danube law was signed on May 11, 1938. After the annexation of Austria , the German Reich took over the construction of the waterway. With the implementing regulation of July 26th of the same year, the preliminary contracts were repealed. The now chosen route of the canal along the so-called Mindorf Line also showed parallels to today's Main-Danube Canal.

In 1939, the first preparatory work began near Thalmässing in the Roth district . The course of the canal was measured and marked with red stakes. The farmers had to cut down their forests to a width of 40 meters in the affected sections. In Hilpoltstein , the Deutsche Reichsbahn built a three-track material station with loading crane and connection for a field railway to a material store east of the Swiss mill (near Hofstetten ) and to the construction sites near Pyras and Mindorf . Bridge abutments were concreted for a new country road between the two places that was supposed to cross the canal and the Minbach was laid in a culvert. Remnants of the bridge shell still remind of this project today. In the vicinity, preliminary work was carried out on a test area (150 m × 100 m) for a heavily sunken canal route in the Jura . They should bring experience in sealing the sewer. Today there are two fish ponds on the site.

After the beginning of the Second World War, most of the construction workers were drafted into the Wehrmacht . Polish prisoners of war were used in their place . In 1942 all work on the Mindorf Line was stopped because prisoners and forced laborers were now employed in the Nuremberg industry.

Left: Minbach passage in the planned bridge ramp; left of center and center: two pillar foundations of the planned bridge

Replanning

exhibition of the RMD-AG in the Bavarian State Representation in Bonn , 1965

After the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany , Rhein-Main-Donau AG reverted to its previous rights in September 1949 in order to continue the expansion of the waterway (later known as the European Rhine-Main-Danube Canal). At the same time as the river was being expanded, planning for the Main-Danube Canal was resumed in the 1950s. In April 1955, attempts to determine an optimal standard cross-section were carried out on the Main Canal near Volkach . In 1957 the Hamburgische Schiffbau-Versuchsanstalt determined the dimensions to be used later. The concept of the economy locks for the Main-Danube Canal was developed by the Technical University of Karlsruhe from 1958 onwards. The expansion of the Main was considered complete with the opening of the Bamberg state port on September 25, 1962.

Start of construction on the Main-Danube Canal

Construction of the Main-Danube Canal began in June 1960. In the Duisburg contract between the Federal Republic of Germany and the Free State of Bavaria, financing and implementation were reorganized in 1966. The federal government held two thirds and the Free State of Bavaria one third of the RMD-AG. In 1967 the line from Main to Forchheim was completed, and in 1970 the port of Erlangen opened. In the presence of the Bavarian Prime Minister Alfons Goppel , the so-called northern route (Bamberg-Nuremberg) was inaugurated on September 23, 1972 with the state port of Nuremberg (today Bayernhafen Nuremberg ) .

Even before the construction work began, there was a discussion about the future status of the waterway under international law . During the Cold War , critics feared an internationalization of the canal and "competition from red fleets" of the socialist countries bordering the Danube. On behalf of the German Waterways and Shipping Association and the Bavarian State Ministry for Economic Affairs, Infrastructure, Transport and Technology , the legal scholar and international law expert Günther Jaenicke prepared a study published in 1973. This came to the conclusion that the Federal Republic of Germany was not obliged to internationalize the canal or to grant traffic rights to other states. Many of these fears were later put into perspective by the fall of the Iron Curtain and the development of the European Union .

Katzwanger dam breach 1979

On March 26, 1979, a dam breach with serious consequences occurred on the then new Nuremberg-Roth line above the Nuremberg district of Katzwang ( coordinates of the point in the dam ). Small rivulets were already visible at the western dam foot at around 1 p.m. Experts called in by concerned residents saw no danger in this. At around 3:50 p.m. the canal embankment collapsed over a length of 10 to 15 meters. Around 350,000 cubic meters of water fell from the Eibach canal, which was partially flooded and not yet released for shipping, through the town center of Katzwang and then further into the Rednitz valley, which is about 25 meters deeper than the canal.

The force of the water was so great that it washed away craters up to ten meters in size and carried away cars, people and buildings. Several people had to be rescued from their house roofs by helicopters with life jackets. In addition to the until about 19:00 expiring canal water many disabled spectators the salvage work. These had rushed to the site shortly after the dam breach became known. Even warnings that a nearby cross dam could break could not prevent people from going as far as the immediate vicinity of the break. A 12-year-old girl drowned during a rescue operation in the village. In addition, five injured people, 14 destroyed and 250 damaged houses as well as property damage equivalent to approx. 12 million euros are included in the balance sheet of the disaster.

After the accident, criticism of the crisis management of the city of Nuremberg and the builder of the canal was loud. The accident showed that the authorities were not prepared for the dam breach. The disaster alarm was only triggered at 6 p.m., so that many aid workers, including soldiers from the German Armed Forces and the US armed forces stationed in the surrounding area, learned of the disaster too late. The mayor of Nuremberg, Willy Prölß, and the Bavarian Minister of the Interior, Gerold Tandler, arrived at the scene of the accident that evening .

The “negligent causing of a flood” case was closed in 1981 by the public prosecutor's office. An expert commission blamed the chain of 14 individual factors for the accident. The experts considered “hydraulic processes in the ground, especially in the area of the intersection with the long-distance water pipeline to Fürth” as the cause. Groundwater that had penetrated the pipe shaft had created cavities under the asphalt- sealed joints in the concrete floor. As a result, the joints were broken, whereupon the sewer bed was further submerged and finally collapsed. In the years after the disaster, the entire sewer route was examined for weak points and retrofitted at critical points for the equivalent of around 40 million euros. The analysis of the cause also resulted in a change in the routing of the embankments, which were now planned as deeply as possible.

Completion of the Main-Danube Canal

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Main-Danube Canal was increasingly politically controversial. In addition to doubts about safety and questions of international law, the construction of the canal was now an environmental controversial issue. In particular, the expansion of a 34-kilometer section of the Altmühl and its negative effects on the flora and fauna were the subject of controversial discussions. Overall, the project increasingly lost acceptance. In addition, there were cuts in construction funds and a change in course for the then Federal Minister of Transport, Volker Hauff . In order to support the respective warehouses, different goods transport volumes were forecast, from which benefit-cost ratios were derived.

On behalf of the Federal Minister of Transport, Planco Consulting GmbH carried out a cost-benefit calculation in 1981 . This envisaged a traffic volume of only 2.7 million tons per year for the Main-Danube Canal and a benefit-cost ratio of 0.52: 1. Transport Minister Hauff then described the project as "pretty much the stupidest project since the Tower of Babel." As a result of a cabinet decision of January 27, 1982, Federal Minister Hauff negotiated with the Bavarian state government about a "qualified termination" of the project. The international action group against the construction of the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal , an amalgamation of all federal German and Austrian nature conservation associations and the railway workers' unions in Germany, collected 700,000 signatures against the further construction of the Main-Danube Canal in the same year.

An argumentation study by the Ifo Institute Munich commissioned by the proponents , on the other hand, estimated a traffic volume of 5.5 million tons per year. In the subsequent negotiations, the Free State of Bavaria insisted on the fulfillment of the existing contracts. After the change of government in November 1982, the federal and state governments agreed in a joint protocol: The Main-Danube waterway should be completed quickly so that it could be used as soon as possible. In addition, the transfer of water from the Danube and Altmühl to the Regnitz-Main area should be made possible immediately.

As early as January 14, 1982, the cabaret artist Dieter Hildebrandt dedicated an episode of his television program Scheibenwischer to the Main-Danube Canal and caused a media scandal. Together with his colleagues Gerhard Polt and Gisela Schneeberger, Hildebrandt satirized the "Alfons-Goppel-Prestige-Tümpel", which eradicates the native fauna, but instead "brings sewer rats new living space and taxidermists secure jobs". The waterway, which has been planned for over half a century, would probably cut through an “annoying recreational area”, but ultimately only “completely intact landscapes could survive this canal”. The Bavarian state government protested at the broadcaster Free Berlin because of alleged allegations and a "anti-Bavarian program".

After 32 years of construction, the last section of the canal was officially opened on September 25, 1992 by the then Bavarian Prime Minister Max Streibl near Pierheim . The Deutsche Bundespost issued a special postage stamp for the occasion . The stamp shows the wooden bridge spanning the canal near Essing . From 1960 to 1992, the equivalent of around 2.3 billion euros was invested in the construction of the waterway. Almost 20% of this flowed into environmental protection projects , especially on the southern route . The annual operating costs of 15 million euros are covered to 20% by income from fees. The rest is borne by the Federal Ministry of Transport .

The Rhein-Main-Donau AG was on 1 January 1995 for 800 million marks from the Bayernwerk AG (77.49%), the Lech-electric power stations (14.0%) and the energy supply Schwaben (8.5 %) accepted. As a result of the merger of Bayernwerk AG with PreussenElektra in 2000, RMD-AG today belongs to Uniper with 77.49% , while Lechwerke is almost 90% part of the E.ON Group. In 1997, Energie -versorgung Schwaben merged with Badenwerk to form the EnBW group.

The planned expansion of the Danube between Straubing and Vilshofen along the Rhine-Main-Danube waterway is still controversial. Proponents argue that the cost structure of inland shipping requires ever larger ship units and thus larger lock dimensions, loading depths and a safe minimum water depth. The opponents argue with the disadvantages for the environment and with the fact that inland shipping is declining overall.

Expansion and dimensions

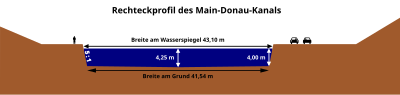

Typical cross-section of the canal

The standard cross-section of the Main-Danube Canal is trapezoidal with a bottom width of 31 m and a water level of 55 m. In the middle the water depth is 4.25 m, at the outer edge of the bed 4.00 m. The canal has a slope of 1: 3 and a dam slope of 1: 2. In the few sections with a rectangular profile, for example in Nuremberg, the bottom width is 41.45 m and the water level is 43.1 m.The bank here has a slope of 5: 1. The depth is again 4.25 m or 4.0 m.

Control ship on the canal

The Main-Danube Canal has the waterway class Vb. It is approved for large motor cargo ships with a maximum length of 110 meters, a width of 11.45 m and a discharge depth of 2.7 m. The largest registered vehicle is a pushed convoy with a length of 187 m and a width of 11.45 m. Ships up to 135 m in length and 11.45 m in width may enter the canal with a special permit. The maximum clearance height must not exceed 6.0 m.

Locks

on the right the pump house for pumping water into the apex of the canal and into the Dürrlohsee (above behind the pump house)

The difference in height from the Main to the apex, the so-called northern route , 175.1 m, is overcome by eleven locks. From the apex to the Danube, the difference in altitude is 67.8 m, which is overcome by the five locks on the southern stretch . At the junctions, the Danube effectively runs 107.3 m above the level of the Main. The 16 locks between Bamberg and Kelheim have to cope with a total difference in height of 242.9 m.

The locks of the Main-Donau-channel case have heights from 5.29 to 24.67 m and a uniform effective length of 190 m and a chamber width of 12 m, the locks of the 13th passage levels are saving locks ; they have relatively little water loss. The other locks are operated with water from the Regnitz and Altmühl. The locks of the three barrages with a drop height of 24.67 m ( Leerstetten , Eckersmühlen and Hilpoltstein) have the highest drop heights of all locks in Germany. In order to prevent these high canal locks from becoming a bottleneck, a system had to be developed in order to be able to fill and empty them in approximately the same time as the much lower river locks of the Main and Danube. The base barrel system used achieves lifting and lowering speeds of up to 1.7 meters per minute, which is roughly five to six times that of river locks.

All locks are operated remotely from four remote control centers (Neuses, Kriegenbrunn , Hilpoltstein, Dietfurt an der Altmühl). The headquarters are manned by two (day shift) and one employee (night shift). For this purpose, the locks were modernized from 2001 to 2007 and the control panels with relay technology were replaced by computers and a programmable logic controller . This cost around 1.3 million euros per lock. The construction of the Erlangen lock is planned for 2023 to 2028 and the construction of the Kriegenbrunn lock for 2022 to 2027.

List of locks on the Main-Danube Canal

| Surname | completion | Canal kilometers | Section length (km) | Altitude (EW m + NN) | Height of fall (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bamberg lock | 1966 | 7.42 | 5.87 | 241.80 | 10.94 |

| Strullendorf lock | 1967 | 13.29 | 12.60 | 249.21 | 7.41 |

| Forchheim lock | 1964 | 25.89 | 6.97 | 254.50 | 5.29 |

| Hausen lock | 1968 | 32.86 | 8.19 | 266.50 | 12.00 |

| Erlangen lock | 1970 | 41.05 | 7.61 | 284.80 | 18.30 |

| Kriegenbrunn lock | 1970 | 48.66 | 20.43 | 303.10 | 18.30 |

| Nuremberg lock | 1971 | 69.09 | 3.73 | 312.50 | 9.40 |

| Eibach lock | 1978 | 72.82 | 11.50 | 331.99 | 19.49 |

| Leerstetten lock | 1980 | 84.32 | 10.62 | 356.66 | 24.67 |

| Eckersmühlen lock | 1985 | 94.94 | 4.05 | 381.33 | 24.67 |

| Hilpoltstein lock | 1989 | 98.99 | 16.47 | 406.00 | 24.67 |

| Bachhausen lock | 1989 | 115.46 | 16.47 | 406.00 | 17.00 |

| Berching lock | 1991 | 122.51 | 7.05 | 389.00 | 17.00 |

| Dietfurt lock | 1984 | 135.26 | 12.75 | 372.00 | 17.00 |

| Riedenburg lock | 1982 | 150.83 | 15.57 | 355.00 | 8.40 |

| Kelheim lock | 1981 | 166.06 | 15.23 | 346.60 | 8.40 |

bridges

over the apex to the east of Hilpoltstein , behind it on the east side the parallel bridge of the federal motorway 9

The Main-Danube Canal is crossed by a total of 115 bridges that span the waterway without piers . Their lower edge is at least six meters above the water level. Among other things, the federal highways 3 , 6 , 9 and the federal highways 2 , 8 , 14 , 22 , 299 and 470 cross the Main-Danube Canal. There are railway bridges over the canal on the main lines Fürth – Würzburg , Fürth (Bavaria) –Cadolzburg , Nuremberg – Crailsheim , Treuchtlingen – Nuremberg and the high-speed line Nuremberg – Ingolstadt . Partially closed branch lines that cross the canal are the Strullendorf – Ebrach , Forchheim – Höchstadt and Erlangen-Bruck – Herzogenaurach railway lines .

The bridge architecture ranges from simple functional buildings from the 1960s and 1970s to examples of modern architecture. Special bridges over the Main-Danube Canal are (from north to south):

- the new chain bridge in Bamberg, completed in 2010 (length: 72 m)

- the new construction of the Luitpold Bridge in Bamberg, completed in 2006 (length: 101 m)

- the Heinrichsbrücke in Bamberg , built in 1974 and meanwhile extensively renovated . The B 22 crosses the canal and the eastern branch of the Regnitz on this 270-meter-long steel structure .

- The pedestrian and cycle path bridge in Forchheim, built in 2002, is a cable-stayed bridge with a length of 117.5 meters.

- The 85 meter long A 6 bridge between Neuses and Katzwang was expanded to six lanes from 2009. As a special feature, the new bridge elements were built next to the traffic routes in order to avoid traffic obstructions on the motorway and canal and then pushed in as a whole, and the previous structure was removed in two sections.

- The 141-meter-long Main-Danube Canal Bridge on the Nuremberg – Ingolstadt high-speed line .

- The Biberbach bridge (near Beilngries) is a steel structure completed in 1991 with a length of 247 meters.

- The Griesstetten- Dietfurt an der Altmühl bridge built in 1990 and made of prestressed concrete (length 124 meters)

- The 220 meter long cable-stayed bridge Meihern-Deising in the municipality of Riedenburg was built in 1988.

- The Untereggersberg bridge , a few kilometers down, is a suspension bridge . It was opened to traffic in 1988.

- The wooden bridge near Essing , built in 1986, is a pedestrian and cycle path bridge in the town of the same name . The 189.91 meter long structure was the longest wooden bridge in Europe until 2006.

- The pedestrian bridge on Torhausplatz in Kelheim, completed in 1988

In addition, the canal itself crosses some streets and rivers. Five concrete trough bridges were erected for this purpose. In the 1970s, steel trough bridges with a length of up to 219 meters (Rednitztal canal bridge) were built over the river valleys of Zenn , Rednitz and Schwarzach . Smaller rivers such as the Middle Aurach and some brooks flow through a twisted or culvert under the canal bed.

Water balance

In order to supply the locks of the Main-Danube Canal with sufficient water, an elaborate regulation system was created which, in addition to the canal, also supplies the water-poor Regnitz and Main river systems with water from the Danube and Altmühl. There are five pumping stations at the locks between Kelheim and Bachhausen , each of which can transport up to 35 cubic meters of water per second into the apex position and into the Dürrloh reservoir . This reservoir has a total volume of two million m³ and adds 1.75 million m³ of usable process water to the storage volume of the apex management. It was built as an open water reservoir between 1994 and 1996 through the generous expansion of the existing Dürrloch pond to the north. The pumping stations use the lower electricity prices at night and on weekends.

For the water supply of Regnitz and Main, a maximum of 21 m³ of water per second can be pumped further into the Rothsee via the northern section of the Main-Danube Canal . Before this, this water flows through a hydroelectric power station with 3 MW electrical output at the Hilpoltstein lock . Before the Eckersmühlen lock, it is diverted from the upper water into the immediately neighboring Rothsee. If necessary, up to 15 m³ / s of water are channeled from this reservoir into the Rednitz tributaries Roth and Schwarzach. In the case of low and medium discharges , the water is discharged via the two turbines of the associated power plant, which are designed for a flow rate of 1.0 m³ / s and 5.0 m³ / s, with a total of 750 kW with a 14.4 m head, a further 9.0 m³ / s can be diverted past the power station. Between 1994 and 2008, an average of 97 million m³ of water was transferred into the Rothsee annually, the natural inflow of the Kleine Roth amounts to approx. 10 million m³, 106 million m³ were released. The average annual electricity generation by hydropower is 2.7 million kWh, which covers a further part of the pump energy used.

Regardless of this, excess water is taken from the Altmühl by the town of Ornbau and fed into the Altmühlsee via the five-kilometer-long Altmühl feeder . From there it reaches the Kleiner Brombachsee and the directly adjacent Großer Brombachsee via the 8.7 km long Altmühlüberleiter . If there is insufficient water in the Regnitz, water is released from the Brombachsee into the lower reaches of the Brombach . This water also flows to the Regnitz and the Main via the Swabian Rezat and Rednitz. In this way, between 1999 and 2008, an average of 30.5 million m³ was released from the Brombachsee towards the Main every year. In the long term, an average annual transfer through the entire system of 150 million m³ of water is expected, 5/6 of which via the Main-Danube Canal.

business

Freight transport

Between 1993, when the Main-Danube Canal was open all year round for the first time, and 2012 an average of 6.38 million tons of goods was transported on it every year. In 2016, the freight volume reached its low point of 4.8 million tons. According to estimates, the technically possible capacity of the Main-Danube Canal is between 14.2 and 18 million tons per year, three to four times as much.

After the fall of the Iron Curtain, the Bavarian Minister of Transport , August Lang, assumed “at least 10 million tons” per year in the medium to long term, and the federal transport route plan was at least 8.5 million tons. So far, this amount has only been reached in the peak year 2000. The property developer Rhein-Main-Donau AG even predicted in 1992 that around 18 million tons of freight would be transported on the waterway as early as 2002.

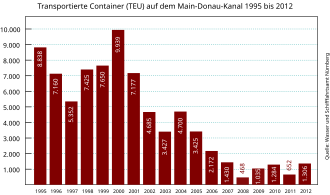

Container traffic

In 2007, 1,430 standard containers ( TEU ) were transported on the Main-Danube Canal . In the peak year 2000, the number of containers transported was almost 10,000. The ever lower capacity utilization with container ships is still one of the main arguments of opponents of the Rhine-Main-Danube project. The Federal Environment Agency found that the transport of classic bulk goods such as stones, mineral oils or ores on German inland waterways shows “a downward trend”. In contrast, container traffic is forecast to "continue to develop positively". On the Main-Danube Canal, however, large, modern container ships have the disadvantage that they can only navigate the canal with two layers because of the 6 m headroom of bridges.

In response to a written request from Eike Hallitzky, Member of the Bavarian State Parliament ( Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen ), the Bavarian State Ministry for Economic Affairs, Infrastructure, Transport and Technology announced on June 23, 2008, among other things, that the Bavarian state government “is not concerned with the modes of transport Trucks , trains and inland waterway vessels chase goods from one another ”. In addition, three-layer container traffic on the Main-Danube Canal is "not impaired by the bridge heights, but by the fluctuations in the water level as a result of the surge and sinking effect when the lock is emptied or filled".

Goods transported in 2015

The transport volume in alternating traffic between the Main-Danube Canal and the Danube (Kelheim lock) consisted of the following goods in 2015 (figures in tonnes):

| Goods division / quantities in tons | Towards the Danube | Direction Main | All in all |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food and feed | 439.420 | 769.692 | 1,209,112 |

| Agricultural, forestry and allied products | 33,494 | 644.373 | 677.867 |

| Ores and metal waste | 368.029 | 14,955 | 382.984 |

| Iron, steel and non-ferrous metals | 238,898 | 247.053 | 485,951 |

| fertilizer | 383,684 | 178.033 | 561.717 |

| Stones, earth (including building materials) | 259.102 | 14,955 | 317.092 |

| Petroleum products | 15,441 | 7,851 | 23,292 |

| Solid fuels | 219.481 | 10,780 | 230.361 |

| Other goods | 29,638 | 60,446 | 95.314 |

| Chemicals | 52,581 | 1,985 | 54,566 |

| All in all | 2,045,098 | 1,993,158 | 4,038,256 |

Ports

The ports of Bamberg, Nuremberg and Roth once belonged to the state port administration of Bavaria. In 1995, it was decided to transfer it to private legal forms with Hafen Nürnberg-Roth GmbH , in which the state port administration held an 80% stake. On June 1, 2005, the Bayernhafen Group and a number of other operating companies took the place of the Bavarian port administration.

Shipping cargo handling in tons at the ports of the Main-Danube Canal:

| Location (MDK km) |

port | Ship cargo handling (in tons) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 - 4 east | Bamberg harbor | 362,000 |

| 22 W - 24 O | Eggolsheim harbor | - numbers are missing - |

| 31.1 east | Forchheim land | Passenger shipping |

| 45.5 west | Erlangen Lands | 81,200 |

| 48.0 east | Frauenaurach land | - under renovation - |

| 55.0 east | Land of Fürth | 68,000 |

| 65.0 west | Gebersdorf | - Shipyard - |

| 71-72 west | Nuremberg harbor | 380,000 |

| 91.0 west | Land Roth | 57,000 |

| 114.2 east | Mühlhausen land | 35,000 |

| 137.5 east | Dietfurt land | 112,000 |

| 149.8 west | Land Riedenburg | - see Kelheim - |

| 171.2 west 2411 D south |

Kelheim harbor and Riedenburg land | 407,000 |

Flora and fauna

During the construction of the Main-Danube Canal, the equivalent of almost 460 million euros was spent on compensatory measures for nature. In contrast to the northern section, which was still largely realized with a standard cross-section, flat banks and still water zones were created on the southern section. When the canal was opened in 1992, Hubert Weiger from the Federation of Nature Conservation in Bavaria described it as "floral decorations on nature's corpse coffin". Ten years after the canal was completed, the Bund Naturschutz determined that the destruction of 600 hectares of wetland led to a sharp decline in the diversity of fish, birds, amphibians and plants. Rare animals such as the yellow-bellied toad or the water shrew have partly disappeared. An overall ecological balance after the construction of the Main-Danube Canal has not yet been drawn up.

The so-called neozoa are considered to be a further ecological danger from the waterway . These are animal species that are introduced through human action into areas where they can displace native species. Due to the lack of predators, these new animal species can reproduce disproportionately there. Among other things, the great humpback shrimp and the Danube shrimp came from the Danube to the Rhine via the Main-Danube Canal .

Water quality

In 2008, the Main-Danube Canal had water quality class II (moderately polluted) throughout its entire course .

freetime and recreation

The entire Main-Danube Canal has a service route on at least one bank that is open to pedestrians and cyclists at their own risk. Because of its minimal gradients, this trail is a popular hiking route for both of them. Although there is little tourist infrastructure along the canal, especially on the northern route, it has now developed into a popular local recreation area in the Nuremberg metropolitan region . The southern section is developed for tourism at a high level. Passenger ships operate daily between Riedenburg and Kelheim from April to October. Bicycles can be taken along for free and at any time. The Main-Danube Canal is part of the Five Rivers Cycle Path and Altmühltal Cycle Path .

Various river cruise operators have now (2015) discovered the canal as an attractive connecting route that allows cruises from Basel or Rotterdam / Amsterdam via Nuremberg and Regensburg to Vienna and Budapest.

The swim course of the long-distance triathlon Challenge Roth is swum in the Main-Danube Canal near Hilpoltstein. The ship traffic pauses during the competition. Until 2017, an approximately 14 km long section of the marathon route ran from the Leerstetten lock to the Eckersmühlen lock on the service route of the Main-Danube Canal; after that the route was changed, today only a small part is on the canal.

On the Main-Danube Canal there are boathouses of the rowing club Nuremberg, the rowing club Erlangen from 1911 and the Erlanger hiking rowing society Franconia.

Since the canal was completed, the water has become less popular with anglers . This is mainly due to the relatively strong current. Experienced anglers still appreciate the water, especially for its carp , perch and pikeperch .

"Incidentally, it is also the case that many projects have been made with great promises, I am now thinking of the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal, so shipping and cargo shipping should flourish there. In the meantime it has become more of a paradise for water sports enthusiasts, but it has become a very expensive paradise. "

art

It is about two walls aligned over the apex posture of the canal, see also this and this picture.

There are numerous modern works of art on the Main-Danube Canal. The monument to the posture of the vertex , which indicates the course of the European main watershed, was created by the artist Hannsjörg Voth . In Essing, several artists set up the art trail between rock and river on an old run of the Altmühl , sometimes with changing objects. At Rednitzhembach there are a total of 24 sculptures over a distance of two kilometers. In 2007, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome between Freystadt and Dietfurt, 27 so-called European benches were set up. The benches are in the respective national colors for the member states of the European Union .

Cities and municipalities on the canal

Cities and municipalities in the order of the canal course from north to south:

- Bamberg district

- City of Bamberg

- Bamberg district

-

Forchheim district

- Hallerndorf , Eggolsheim , Forchheim , Hausen

- Erlangen-Höchstadt district

- City of Erlangen

- City of Fürth

- Fürth district

- City of Nuremberg

- District of Roth

- City of Schwabach

- District of Roth

- District of Neumarkt in the Upper Palatinate

- District of Eichstätt

- District of Neumarkt in the Upper Palatinate

-

District of Kelheim

- Riedenburg , Essing , Kelheim

literature

- Michael Brix (Ed.): Main-Danube Canal . Substitute landscape in the Altmühltal. Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 978-3-7667-0887-8 .

- Bernd Engelhardt: Excavations on the Main-Danube Canal . Archeology and history in the heart of Bavaria. Ed .: Rhein-Main-Donau AG, Munich - Department for Public Relations and Economics. [Buch am Erlbach], Leihdorf 1987, ISBN 3-924734-10-0 .

- Christian Glas: Economic geographic reassessment of the Main-Danube Canal . In: Munich studies on social and economic geography . tape 40 , Munich University Writings. Lassleben, Kallmünz / Regensburg 1996, ISBN 3-7847-6540-8 (dissertation at the Ludwig Maximilians University Munich 1995).

- Dieter Hildebrandt , Gerhard Polt , Gisela Schneeberger : Our Rhine-Main-Danube Canal . Windshield wiper broadcast from January 14, 1982, SFB / ARD . Heyne, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-453-35631-4 ( online at Youtube [accessed September 15, 2013]).

- Tristian Jones: Stuck . Caught on the Main. 1st edition. Pietsch, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-613-50412-X (Original title: The Improbable Voyage . Translated by Irina Zeiss, Willi Zeiss).

- Markus Morgenstern: Water balance and modeling of the groundwater system of the Kelheim Bowl . Dissertation-Verlag NG-Kopierladen, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-933214-01-7 ( dissertation at the Ludwig Maximilians University Munich 1997).

- Lothar Schnabel, Walter E. Keller: From the Main to the Danube . 1200 years of canal construction in Bavaria: Karlsgraben, Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal, Rhine-Main-Danube Canal. Bayerische Verlagsanstalt, Bamberg 1984, ISBN 3-87052-361-1 .

- Boy Heinrich Timmermann: the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal and its impact on European inland navigation . Munich 1994 (dissertation at the Ludwig Maximilians University Munich 1995 - without ISBN ).

- The Rhine-Main-Danube Canal . The pros and cons of its manufacture. In: Hubert Weiger (Ed.): Iris books . Number 504.Schulz , Munich 1985, ISBN 3-8162-0504-6 .

- Martin Eckoldt (Ed.): Rivers and canals, The history of the German waterways . DSV, Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-88412-243-6 .

- Dieter Wulf: The Rhine-Main-Danube shipping route . In: Geosciences in Our Time . tape 1 , no. 1 . Verlag Chemie GmbH, Weinheim 1983, p. 19–28 , doi : 10.2312 / geosciences.1983.1.19 .

- Rolf-Peter Rolef: 68 locks to the Black Sea, ISBN 9783753130446

- Deutscher Kanal- und Schifffahrtsverein Rhein-Main-Donau eV (Ed.) (1982): Plea for the Main-Danube Canal . Bulletin 39. Nuremberg: DKSV. hdl.handle.net

cards

- Karin Brundiers, Harald Utecht: Danube Handbook . [Part] 1., MDK: from Bamberg to Kelheim, Danube: from Kelheim to Passau. With Main-Danube Canal. DSV, Hamburg 1992, ISBN 3-88412-149-9 .

- Wyn Hoop , Andrea Horn: Main, Main-Danube Canal, Danube: Mainz-Passau / Jochenstein . 2nd Edition. Edition Maritim, Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-89225-254-8 .

- Walter E. Keller: The Main-Danube Canal in the Altmühltal Nature Park . Berching - Kelheim - Regensburg . Danube breakthrough near Weltenburg . In: yellow paperback guide . Keller, Treuchtlingen 1994, ISBN 3-924828-64-4 (special edition for Altmühltal passenger shipping, Renate Schweiger, Dietfurt / Kelheim).

- Andreas Saal: Main / Main-Danube Canal waterway map . From the Rhine to the Danube. Edition Maritim, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-89225-467-2 .

- Lothar Schnabel, Walter E. Keller: Cycling and hiking on the Ludwig Canal and Main-Danube Canal . Between Bamberg and Kelheim. In: series of yellow paperback guides . Wek-Verlag , Treuchtlingen / Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-934145-60-3 .

- Heinz Squara: By boat on the Main-Danube Canal . MDK and Altmühl . From Bamberg to Kelheim, 171 km, 16 locks; Travel stations: Bamberg , Forchheim , Nuremberg , Berching , Beilngries , Riedenburg , Kelheim [with fairway sketches , buoys , locks, all travel stations, ports and berths ]. In: Yacht Club Info Board Travel Guide . Sqaura, Bensheim 2006, ISBN 978-3-925640-31-5 .

Web links

- Literature on the Main-Danube Canal in the catalog of the German National Library

- Hans Grüner's pages on the “New Canal” with pictures of all locks

- 25 years of the Main-Danube Canal - the series of images for the anniversary in detail and b / w photography (contains high-resolution images, large amounts of data, therefore possibly long loading times)

- Directory of all bridge clearance heights on the Main-Danube Canal

- The Main-Danube Canal turns ten years old , press article by the "Bavarian Landeshorts"

- Wilhelm Doni: History of the Main-Danube Canal

- Main-Danube Canal. In: Structurae

- Wasserbauliche Infrastruktur GmbH (formerly RMD Wasserstraßen GmbH as an independent company under the umbrella of RMD AG)

- Danube Waterways and Shipping Office MDK

- Bernhard von Zech-Kleber: Rhine-Main-Danube Canal In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria (August 22, 2012)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Lengths (in km) of the main shipping routes (main routes and certain secondary routes) of the federal inland waterways ( memento of January 21, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Federal Waterways and Shipping Administration

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Directory E, Ser. No. 32 of the Chronicle ( Memento from July 22, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Federal Waterways and Shipping Administration

- ^ City of Fürth: Official city map 1969.

- ↑ How the Main-Danube Canal became a big flop - 22 years after its opening, the Main-Danube Canal has developed into a magnet for tourists. The freight transport, on the other hand, for which it was built, slackens considerably. In: Die Welt , November 9, 2014.

- ↑ 20 years of the Main-Danube Canal: Ship ahoy? Are you kidding me? Are you serious when you say that. Hoi, a ship! In: Mainpost , September 28, 2012

- ↑ Inland waterways order (BinSchStrO) § 12.05 ascent

- ↑ Nuremberg Waterways and Shipping Office: Height map of the Main-Danube Canal

- ↑ M. Eckoldt (Ed.): Rivers and canals, The history of the German waterways. DSV-Verlag, 1998, pp. 451-457.

- ↑ Ralf Molkenthin: Roads made of water, technical, economic and military aspects of inland navigation in Central Europe in the early and high Middle Ages . LIT Verlag, Münster 2006, ISBN 3-8258-9003-1 , p. 54-81 .

- ^ Eduard Faber: Memorandum on the technical draft of a new Danube-Main waterway from Kelheim to Aschaffenburg. . Association for the improvement of river and canal shipping in Bavaria. Nuremberg 1903, as of October 30, 2009.

- ↑ Siegfried Zelnhefer: A dream becomes reality. The completion of the Main-Danube Canal. In: Nürnberg Heute , 52, July 1992.

- ↑ Foundation. Rhein-Main-Donau AG, archived from the original on October 6, 2007 ; Retrieved January 6, 2007 .

- ↑ see Reichsgesetzblatt Part II 1938, p. 149 (on Commons)

- ↑ a b c Wilhelm Doni: Overview of the history of the Main-Danube Canal . As of October 10, 2009.

- ↑ Ernst Wurdak, Hans Trögl in Heimatkundliche forays , Issue 21, district Roth

- ↑ Panoramio photos by Artur Lutz: The Mindorf Line of the Main-Danube Canal. Construction of the planned bridge on a display board

- ↑ a b c Nuremberg Waterways and Shipping Office: Main-Danube Canal timetable . As of October 10, 2009.

- ↑ "The crowning glory of privatization" Under Stoiber, the energy supplier Bayernwerk is to be sold. In: the daily newspaper , July 15, 1993.

- ^ Günther Jaenicke : The new major shipping route Rhine-Main-Danube; an international law investigation into the legal status of the future Rhine-Main-Danube-Grossschiffahrtsstrasse. Athenäum Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1973.

- ↑ M. Eckoldt (Ed.): Rivers and canals, The history of the German waterways. DSV-Verlag, 1998.

- ↑ A water roller destroyed Katzwang . In: Nürnberger Zeitung , October 24, 2009.

- ↑ Memorial plaque of the interest group Katzwang der Kanalanlieger eV at the scene of the accident (see picture )

- ↑ They fell into the water from the balcony. In: Hamburger Abendblatt . March 27, 1979. Retrieved May 6, 2016 .

- ↑ Dam break on the Main-Danube Canal . In: Radio 8 , March 26, 1979.

- ↑ Excavated: Katzwang sank in the canal water . In: Nürnberger Nachrichten , October 24, 2009.

- ↑ Andrea Wiedemann: The dam break as a menetekel . As of October 24, 2009.

- ↑ Big broadcast . In: The mirror . No. 50 , 1981, pp. 79-83 ( Online - Dec. 7, 1981 ).

- ↑ Der Spiegel : True Abundance . In: The mirror . No. 4 , 1982 ( online - "A TV satire about the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal hit the Free State of Bavaria: cabaret penetrated the cabinet.").

- ↑ The new diet check has arrived again ( Memento from September 28, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Key date, September 27, 1992 - The Rhine-Main-Danube Canal is inaugurated. wdr.de, September 27, 2012, accessed on December 21, 2016 .

- ↑ Coburger Tageblatt , September 25, 2012, p. 2.

- ↑ Buy power generators Rhein-Main-Donau AG . In: FAZ , July 6, 1994; quoted from: udo-leuschner.de (January 6, 2007)

- ↑ Bachhausen locks and Dürrlohsee in the aerial photo (left the vertex posture ) ( Memento from September 4, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) at: www.muehlhausen-sulz.de

- ↑ a b c Main-Danube Canal - Ships drive over the mountain . As of October 10, 2009.

- ↑ [2] , accessed on October 26, 2020.

- ↑ Kriegenbrunn lock , accessed on October 26, 2020.

- ^ Nuremberg Waterways and Shipping Office: The waterway in figures ( Memento from January 22, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) , as of October 12, 2009.

- ↑ Construction of a new bridge in Katzwang.

- ↑ Photos of the extension canal bridge Neuses on a private website

- ^ Bridge transport to Neuses.

- ↑ a b Nuremberg Waterways and Shipping Office: Dürrlohsee pumped storage facility ( memento of March 9, 2012 in the Internet Archive ). As of October 14, 2009.

- ↑ a b Wasserwirtschaftsamt Ansbach: Overall balance of the transition ( Memento from February 4, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) as of October 14, 2009.

- ↑ a b Christian Sebald Beilngries: The Main-Danube Canal is a complete failure . In: sueddeutsche.de . July 16, 2017, ISSN 0174-4917 ( sueddeutsche.de [accessed November 1, 2017]).

- ↑ a b Rhine-Main-Danube Canal. Freight traffic between forecasts and reality. BR-online, December 10, 2008, archived from the original on March 13, 2011 ; Retrieved October 14, 2009 .

- ↑ The narrow-gauge canal - five years after the inauguration of the controversial Rhine-Main-Danube Canal, the freight expectations have not come close to being fulfilled. In: Zeit online , October 2, 1997

- ↑ Bavarian State Parliament (15th electoral period): Written request from Member of Parliament Eike Hallitzky of April 10, 2008 (PDF; 46 kB) as of October 16, 2009.

- ↑ Traffic report 2014/2015 of the waterways and shipping administration p. 87

- ↑ Numbers and facts. Bayernhafen Bamberg, accessed on December 11, 2010 .

- ↑ Cargo handling in the port of Erlangen since 1974. In: Erlangen.de . City of Erlangen, Department of Statistics and Urban Research, archived from the original on June 20, 2007 ; Retrieved December 11, 2010 .

- ^ Port of Fürth. Infra Fürth, accessed on May 17, 2015 .

- ↑ Numbers and facts. Bayernhafen Nürnberg, accessed on May 12, 2015 .

- ↑ Numbers and facts. Bayernhafen Nürnberg, accessed on May 12, 2015 .

- ^ Port of Mühlhausen. Mühlhausen Jura harbor, accessed on May 15, 2015 .

- ^ Port of Dietfurt. Bavarian State Ministry for Economic Affairs, Infrastructure, Transport and Technology, archived from the original on July 10, 2015 ; accessed on May 12, 2015 .

- ↑ Inland navigation in Bavaria in January 2016. (PDF; 2.5MB) H2100C 201601. In: Statistical reports. Bavarian State Office for Statistics and Data Processing, January 2016, p. 6 , accessed on May 6, 2016 .

- ↑ Foreign animal species in Lake Constance worry researchers . In: Welt online Wissen , as of October 17, 2009.

- ↑ Black Sea Cancer Conquers Rivers . In: Focus online knowledge , as of October 22, 2009.

- ↑ Aquatic neozoa in Lake Constance . on: neozoen-bodensee.de , as of November 29, 2011.

- ^ Government of Middle Franconia: Water quality in the cities of Nuremberg, Fürth, Erlangen and Schwabach ( Memento from February 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) , as of December 2008.

- ↑ Deutschlandradio Kultur, October 11, 2010

- ↑ image monument vertex posture 001 on Commons

- ↑ The sculpture "Vertex Posture" on the Main-Danube Canal. on: www.swetzel.ch , penultimate picture

- ^ Tourism association in the district of Kelheim eV: Erlebnis Kanal. Art trails on the canal. ( Memento from April 5, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) As of October 17, 2009.

Coordinates: 49 ° 11 ′ 17 ″ N , 11 ° 16 ′ 3 ″ E