Edith Junghans

Edith Hahn , née Junghans (born December 13, 1887 in Stettin , † August 14, 1968 in Göttingen ) was a German painter, draftsman and art teacher. She studied art at the Royal Art School in Berlin and successfully passed her exams as an art teacher in 1912. In 1913 she became the wife of the German chemistry professor Otto Hahn , whom she had met in Stettin in 1911. During the time of National Socialism , she achieved special humanitarian services through her courageous intervention and selfless actions. Occasionally in acute danger, it could make a significant contribution to the rescue of those oppressed and persecuted by the Hitler dictatorship .

Life

Childhood, school days and studies (1887–1912)

Edith Junghans was born on December 13, 1887 in Stettin as the only daughter of the respected lawyer and notary Paul Carl Ferdinand Junghans (1859–1915) and his wife Emma Henriette Caroline nee. Johanning (1862–1928) was born in Stettin. She had a sheltered and happy childhood and was initially taught by private tutors, with a focus on a "French education" and learning foreign languages, especially French and Italian. She then graduated from the private high school for girls founded by Wilhelm Gesenius and received the grade “very good” in all subjects when she graduated, which allowed her to study at a Prussian university. The father, appointed royal councilor by Wilhelm II in 1906 , had an artistic and aesthetic education , was also politically active and a leading member of the National Liberal Party in Pomerania . From 1907 until his untimely death in 1915 he was the head of the city council and one of the dignitaries of Szczecin, and in his position he was a particularly generous patron of art and science. The mayors Hermann Haken and Friedrich Ackermann , the archivist Gottfried von Bülow and the liberal rabbi Heinemann Vogelstein belonged to his circle of friends .

Even as a child, the parents, teachers and friends of the family noticed Edith's talent for drawing, who, after initial scribbling, made their first serious pencil and charcoal drawings at the age of seven. With sensitive devotion she devoted herself in the following years to watercolor and portrait painting , which until the end of her artistic activity was her great passion and revealed her special skills.

“Edith Junghans was a talented painter. She started drawing when she was 10 (sic); It is noteworthy that many of her pictures were made almost unacademic even before attending the Royal Art School in Berlin. The actual painterly field and the artist's personal strengths are her still lifes , which - following on from the realism of the French of the 19th century - almost represent a new objectivity of the 1920s. Her works have a very personal language of expression, transparency and bright colors create a special visual atmosphere. "

From 1907 to 1912 Edith Junghans studied at the Royal Art School in Berlin with the professional goal of becoming a drawing and art teacher. With the support of her parents, she used the semester break on long art trips to France and especially Italy. There - in Santa Margherita Ligure on the Riviera - she created her only self-portrait in 1909 , a pencil drawing in her sketchbook , which she made in her room in the Grand Hotel Miramare .

Marriage to Otto Hahn (1913)

In June 1911 she met the 32-year-old chemistry professor Otto Hahn in Stettin , who took part in a conference organized by the Association of German Chemists and had to give the main lecture on the properties of the mesothorium and radiothorium . Monika Scholl-Latour, the sister of Peter Scholl-Latour , writes in her report:

“It was June 11, 1911, on the Baltic Sea with its fresh, prosaic magic, which was once Germany's lover much more inclined than any Italian or Spanish beach romance today. The newly appointed associate professor of chemistry in Berlin, 32-year-old Otto Hahn with the perky, twisted mustache, took part in a steamboat trip organized by the Association of German Chemists in Stettin that day. The trip should go from the port city at the mouth of the Oder over the ' Große Haff ' to one of the most popular German seaside resorts at the time, to Swinoujscie .

By chance there was also a Miss Edith Junghans on deck, a highly gifted, sensitive trainee at the Royal Art School in Berlin, a gentle beauty with big dark eyes, 23 years old. Fraulein Junghans must have liked the cheerful professor on the steamer at once. In any case, she looked for a place on deck so that she could always sit across from him. His funny blue eyes made her curious. "

Otto Hahn recalls in his autobiography Mein Leben :

“At the end of the congress there was a big steamboat trip from Stettin to the Baltic Sea. Here I met a Miss Edith Junghans. At the request of her parents, she had come to the excursion from Berlin, where she attended the Royal Art School, because her father was the head of the city council in Stettin and had to take part in the honors of the city along with other senior men on the excursion. [...] I sat down next to her and did not leave her side until the steamer returned to Stettin. Another meeting took place in the summer when Miss Junghans went on a four-week trip to Rome with her school . The occasional correspondence remained until the next year.

At Pentecost in 1912 we arranged to meet in the seaside resort of Misdroy , where Miss Junghans' parents wanted to spend the festive season. We met 'to mutual surprise' - we had agreed that beforehand - on the promenade. There I was officially introduced to my parents. [...] On October 5th I showed Miss Junghans the recently completed Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in Berlin-Dahlem , and we got engaged on the walk to nearby Grunewald . The official engagement took place in Stettin on November 7th, 1912. "

When she got engaged , Edith gave her Otto a pen drawing made in September of the Glambecksee near Stettin, in which - according to an entry in her notebook - she "often bathed wildly in it with Otto". Swimming, like all sports that had anything to do with water, had been one of her great passions since Edith was a child, and she had no reservations about swimming in the Baltic Sea, even in freezing temperatures in Miedzyzdroje, where her parents owned a summer house . Otto Hahn always admired his wife's determination, who was of a delicate, slim and elegant stature. He himself could not follow her inclinations and was - in contrast to Edith - a committed and passionate mountaineer and skier . Otto Hahn writes in My Life :

“My position at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute was initially limited to a few years. However, after a radioactivity department was established at the institute , it was unlikely that I would lose my position after a few years. So I could think of getting married that way. My wedding took place on March 22nd, 1913 in Szczecin. "

“In 1913, at the age of 25, Edith Junghans stopped drawing and watercolors for inexplicable reasons. [...] For the wedding, Edith Junghans gave her husband the watercolor Krug mit Buch , created in 1910 . This picture - which symbolizes 'enjoyment and wisdom', has accompanied Otto Hahn at all stages of his life ", sums up the art historian Brigitte Keller in her contribution after the opening of the" Edith Junghans Memorial Exhibition "on the occasion of the 100th birthday in December 1987 in Munich .

After a short stay in the Hotel Adlon in Berlin, the honeymoon initially took the young couple to South Tyrol and Bolzano . In a letter to her mother dated March 28, Edith wrote:

Looking back, Otto Hahn writes:

“From Bozen we drove on to Lake Garda and stopped in San Vigilio on the quieter east side of the lake. We liked San Vigilio with its wonderful cypress avenue and the simple and pretty hotel so much that we decided to stay here and not go to Brioni as planned . When the last passenger steamer left the place in the evening, we were almost alone with a few painters.

My wife, who was a great swimmer, tried hard to get me excited about the water too. But it was so cold that I ran back to looking for solid ground. So instead we went for walks on the beautiful hills around San Vigilio and on the towering Monte Baldo . Occasional steamboat trips took us to the places in the west and south that were already more open to tourism.

Afterwards we visited the meeting of naturalists in Vienna . There was an official reception there in the Hofburg , where the old Emperor Franz Joseph gave a short address, but soon disappeared again. Then a number of imperial lackeys appeared with full champagne glasses on large trays. The few hundred glasses found their lovers in no time. I remember the haughty drawn-down lips of the lackeys and I was ashamed of this scene at the time. Since sparkling wine was served several times later, all 'naturalists and doctors' probably enjoyed their enjoyment, which was rare and expensive in 1913. "

Berlin (1913-1933)

After returning from their honeymoon, Edith and Otto Hahn moved into their first joint apartment at Ladenbergstrasse 5 in Berlin-Dahlem, near the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in Thielallee. The Austrian physicist Lise Meitner , Hahn's colleague at KWI, wrote a postcard to Edith during a break from work: “We're drinking very good coffee and eating great whipped cream. I was happy to hear from your husband that you had such a wonderful time. ”Lise Meitner was soon joined by a warm, intimate and lifelong friendship that resulted from numerous mutual invitations and many joint activities - for example, walks, house music evenings , Opera and concert visits - was cultivated. Lise Meitner was also the godmother of Otto and Edith's only son, Hanno , who was born in 1922 and who later became a recognized art historian and architecture researcher. Otto Hahn recalls:

“After about 1914 or 1/2 year we wanted to have a child. We didn't get this until 1922, however. My test on living seeds was absolutely positive before then. So I don't know whether it was my fault that our son didn't come until after the war. - But maybe it was the rays after all, as I did above all with Dr. W. Metzener believe. My fellow student Metzener was hired by Knöfler to enrich mesothorium. Around 1910 he worked with very strong preparations. He was married, resp. married when he started this work. He did not have his three children until years later, after he had left Knöfler. - The work of Erbacher on the solubility of radium salts has already been briefly discussed. Apart from his considerable hand damage, nothing seems to have happened to him: of his four children he probably only got most or all of his children after this work. Also Miss Schäfer, who spent many years with us at the ThB from eman. RdTh picked up, had at times considerably sore hands, z. T. through carelessness. But soon she had two nice children as Mrs. Born.

All in all, the danger does not seem to be as great or at least not as permanent as it is suspected in some places. Working with the most powerful radiation sources will of course be much more dangerous in the future. The conditions of the radiation protection have to be checked by the small electrostatic ion testers, above all the blood count has to be checked regularly, as has been done at our institute for a number of years. "

In the 1920s, after Otto Hahn was made a full member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences in 1924 and some time later director of the KWI for Chemistry, the family moved to the nearby Altensteinstraße 48, where Otto and Edith Hahn had their own, Moved into the house designed by the architect Hermann Dernburg . A housing in the rather pompous, built next to the KWI and belonging to the Institute Director Villa rejected both because they feared that their privacy would suffer in the future less. Otto Hahn, as director of the KWI, allowed his colleague Lise Meitner to move into the first floor of the director's villa, where, after some renovations, an eight-room apartment was created, in which she could live in a comfortable atmosphere until her emigration in July 1938 .

In the new house at Altensteinstrasse 48 (today located at Otto-Hahn-Platz), where a housekeeper was also employed, Edith and Otto had a happy time together with their growing son Hanno. Soon several cats and a French shepherd dog, a Briard named Tommy, added to the family idyll. A summer house was also built in the large garden of the property, in which Otto Hahn liked to retreat to write scientific texts and to indulge his passion, smoking cigars, undisturbed. Edith was a staunch opponent of smoking and could never make friends with her husband's passion. Only at evening invitations and social events, which took place exclusively in the so-called master bedroom of the property, did she, more or less, endure this “unhealthy smoking”.

The first guest in the Hahn house was Lord Ernest Rutherford , Hahn's revered teacher during his time at McGill University in Montreal , with whom he was a lifelong friend. Rutherford came to Berlin for a few days at the beginning of May 1929 to give lectures on atomic nuclei and their transformations to the German Chemical Society , and during this time he lived in Altensteinstrasse. On May 5, Otto and Edith Hahn held a large evening party in honor of Rutherford, to which they had invited all their Berlin friends. As you can see from Edith's guest book, the guest list reads like a who's who in the history of science in the 20th century: Ernest Rutherford, Max Bodenstein , Willy Marckwald , Heinrich Wieland , Albert Einstein , Max Planck , Otto von Baeyer , Peter Pringsheim , Hans Geiger , Lise Meitner , Friedrich Adolf Paneth , Max von Laue , Walther Bothe , Kasimir Fajans . Five guests were already Nobel Prize winners, two more were to be honored later. However, one of the Hahn family's closest friends was absent from this memorable evening: Fritz Haber , who was prevented from attending a lecture tour. On his return to Cambridge , Ernest Rutherford wrote to Hahn:

“I got home this morning at 10.15am after a very pleasant journey. We were very comfortable on the train, and I slept peacefully all the way to Harwich . I feel very fit, have already had a good day at work and am still hurrying to inform you of my good arrival. It was really wonderful at home and in Berlin. You and your wife really couldn't have looked after my physical and emotional well-being better. It was a great pleasure to meet you and so many old friends again under such pleasant circumstances, and it was really very nice of you to prepare such original place cards. "

During the National Socialism (1933–1945)

After Adolf Hitler and the NSDAP came to power in Germany on January 30, 1933, difficult times began for Otto and Edith Hahn. Both rejected the new regime. Since they consistently refused to join the NSDAP, although repeatedly asked to join, they were soon accused of "political unreliability". While her husband took up a professorship at Cornell University in Ithaca , New York , in February , Edith tried to continue life in Berlin as unchanged as possible and to intensify dealing with friends. She was deeply unhappy about many of the decisions made by the new government and downright dismayed by various measures. When the physicist James Franck , who was one of her circle of friends, voluntarily resigned from his position as professor of experimental physics at Göttingen University in April 1933 , she was downright shocked. In his statement to the university rector, in which he asked the Prussian minister of education for immediate release from his official duties, Franck had written:

“I have asked my superior authority to release me from my position. I will try to continue working scientifically in Germany. We Germans of Jewish descent are treated as strangers and enemies of the fatherland. They demand that our children grow up knowing that they will never be allowed to prove themselves as Germans. Anyone who was at war should be allowed to continue serving the state. I refuse to make use of this privilege, although I understand the point of view of those who today consider it their duty to hold out in their post. "

An editor of the Vossische Zeitung commented on this: “The step taken by Professor Franck could, if it is read on all pages without zeal and bias as it is meant, help people to reflect. In all probability Franck would not have been affected by the anticipated measures. He refuses to take advantage of it. He doesn't want preferential treatment. The sacrifice he makes could show where the path that one now wants to take is leading. "

In a letter to her friends Ingrid and James Franck dated April 22, 1933, Edith wrote:

“I ponder and grapple about what could be done. And if I didn't want you so much, I might envy you (and it's really not just a phrase) that you are Jews and so have your rights on your side, and we have the shame and the ineradicable disgrace for everyone all times.

And it must have made a great impression. Perhaps you are pleased to hear that I have been asked 20 times from very different quarters: 'Did you read that from Prof. Franck?' I bought the rest of the Voss in our Ullstein branch on Wednesday and sent it to all the people I don't think are completely lost because I think your letter should bring them to their senses and I hope the whole world will respond. "

A truly prophetic letter that has belonged to the Joseph Regenstein Library of the University of Chicago since 1972 and has been loaned by the latter for numerous exhibitions in the USA and Europe on the Hitler dictatorship over the past few decades . (The Regenstein Library is conveniently located exactly at the location of the first Chicago Pile 1 nuclear reactor , which was commissioned on December 2, 1942 under the direction of Enrico Fermi ).

Otto Hahn's lectures in Ithaca ended in June 1933 and he had set out on a trip to California to give lectures at several American universities. But when he received alarming news from Edith, especially about difficulties in Haber's Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry, he broke off his trip and returned to Berlin early

“... in order to try as someone who was not affected by the Hitler laws to help as much as possible. The leaders of the institute had lost their jobs or were in danger of losing them. - I went to Planck and suggested that he bring together the largest possible number of recognized German professors who were not affected, who should write a joint protest against the dismissal of Jewish or partially non-Aryan colleagues and send it to the Minister of Education Rust or other official bodies. I had already found some friends and colleagues for such an action. But Privy Councilor Planck replied: 'If 30 professors stand up today and speak out against the government's actions, then tomorrow 150 people will come to show their solidarity with Hitler because they want the job.' Planck himself was very unhappy, but saw no means of help. [...] As a broken man, Haber went to Cambridge, where he was received very warmly. But he had been seriously ill for a long time, and he could not overcome the deep shock. Haber died on January 29, 1934 in Basel. He could no longer accept an invitation from Professor Weizmann to Palestine . "

In a letter to Otto Hahn on the occasion of his 80th birthday, the physicist and Nobel Prize winner Max von Laue , who together with his wife Magda belonged to the closest circle of friends of Otto and Edith Hahn in Berlin:

“[...] But our friendship had to pass the acid test only in 1933 and afterwards. We thought of Hitler and National Socialism ... the same. And we put what we thought into action whenever possible. How often have you, how often have I helped Jewish acquaintances and other persecuted people spiritually by visiting them and inviting them into our houses, despite all the prohibitions. We also know how to remember practical support by making it easier for them to emigrate, mostly independently of one another. In the Prussian Academy we were able to put the brownie through the bill several times, e.g. in elections. Compared to the extent of the horrific event, this meant little; Our influence was not sufficient for anything else. In any case, it was your masterpiece when Lise Meitner , for whom we were all worried, managed to escape to Holland. "

As an Austrian citizen, Lise Meitner lived personally undisturbed in Berlin-Dahlem until March 1938 and pursued her regular scientific work as a department head at the KWI for Chemistry. When Austria was " annexed " to the German Reich on March 13, 1938, she suddenly became " Reichsdeutsche " and lost her Austrian passport. Although she had been a Protestant (Lutheran) since 1908, she was now in particular endangered due to her Jewish descent, and all of her friends in Berlin were increasingly worried about their safety. Lise Meitner, however, was far less aware of her precarious situation than Edith Hahn, who recognized the impending danger for her and correctly assessed it with her intuitive sensitivity. Edith convinced her husband of the need to act quickly to save Lise Meitner from arrest and probable deportation that has now become possible. Otto Hahn reacted immediately. He immediately informed Carl Bosch , the President of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society , and both of them thought about how to get Lise Meitner to leave Germany for a neutral country. Letters to Education Minister Rust and Interior Minister Frick were answered negatively - "Lise Meitner, as a well-known scientist, would do propaganda against Germany". "The situation became more and more unbearable," said Otto Hahn with concern.

“So Bosch couldn't help, and we decided to get our colleague illegally across the border as quickly as possible. Letters and telegrams then went to Switzerland and Holland - the nervousness kept growing. In July Coster received a telegram from Groningen that he would come to Berlin in person. He had managed to get Lise to cross the border into Holland without a visa, accompanied by Coster. On the evening of July 12th, Professor Coster arrived at my institute. With the help of our long-time friend Paul Rosbaud , Lise Meitner's most necessary clothes and valuables were packed during the night. The night before she left she slept with us on Altensteinstrasse, Coster himself only met her on the train. For urgent emergencies, I gave her a beautiful diamond ring, which I always kept well as an heirloom from my deceased mother.

On the morning of July 13th, Lise Meitner drove secretly with Professor Coster towards the very uncertain day. The danger for Lise Meitner was the multiple checks by the SS on the trains going abroad . We trembled whether she would get through or not. Again and again people who tried to get abroad were arrested on the train and brought back. But Lise Meitner was lucky; she came over the border and was saved. I will never forget July 13, 1938. Niels Bohr then got Professor Siegbahn in Stockholm to offer her a job, and Lise Meitner accepted the offer. - During this same time Edith became seriously mentally ill and had to be taken to the 'Kuranstalten Westend', to Professor Zutt, where she stayed for months. "

After the dramatic preparations for Lise Meitner's emigration, Edith Hahn had suffered a nervous breakdown and was transferred to a Berlin clinic for her own safety. There, in the "Kuranstalten Westend", she was treated and cared for as a private patient by the clinic director Zutt until November 20, 1938. Back home, in a balanced condition and with great interest, she took part in the experiments her husband carried out on the neutron irradiation of uranium in December and was happy about his extensive correspondence with Lise Meitner in Stockholm.

On December 18, at the breakfast table, she was the first to learn from her husband about the surprising formation of barium from uranium , which he and his assistant Fritz Strassmann had detected at the institute the night before, and that from him as a bursting of the uranium atomic nucleus was recognized. It was the discovery of nuclear fission . On December 19, he communicated this result in a letter to Lise Meitner, who, as a physicist, reacted extremely skeptically at first, but since she knew Hahn's mastery in identifying elements well, she did not consider it completely absurd “that such a difficult one Core burst ". Otto Hahn, supported and strengthened by his wife Edith from the beginning, intended to be the only one to report to his colleague and close friend Lise Meitner of the verifying experiments on uranium fission (so named by Hahn) in order to give her the opportunity to act as first to work out a physical interpretation of the radiochemical findings. The physicists in his institute did not find out about the results at first and only through their publication in the journal Die Naturwissenschaften on January 6, 1939. Lise Meitner and her nephew, the physicist Otto Robert Frisch , had a 17-day time and knowledge advantage. which actually enabled them to be the first to publish a physical-theoretical explanation of nuclear fission. They did this on February 11, 1939 in the British specialist journal Nature , and Frisch coined the term nuclear fission , which was subsequently recognized internationally.

The years up to 1945 brought a number of war-related burdens for Otto and Edith Hahn, but also special tasks, to which they devoted themselves with courage and determination. While the scientific work at the KWI for Chemistry could be continued almost without restrictions, her private life in Dahlem changed in many ways. On June 14, 1940 Edith wrote to her brother-in-law Heiner Hahn in Frankfurt am Main:

“Except for a very few familiar and like-minded souls, we hardly meet anyone here in personal contact. At most it would lead to insincerity and prejudice. "

And on September 2, 1940 she informed her brother-in-law:

“Here everything is going on as usual, interrupted by frequent night-time air alarms that reasonable people experience in air raid shelters. We ourselves have not yet been one of these sensible people. "

Edith suffered a lot from the prevailing Nazi conditions, especially after the living conditions for people with dissent and opposition, but especially for Jewish citizens, which became more and more severe year after year. In the long run, she, the daughter of the liberal judiciary Junghans, could no longer endure these conditions. She decided to help and - after consulting her husband - to take care of threatened people. A brave decision, as any support or advocacy for Jews was subject to the death penalty. The publicist and publisher Wolf Jobst Siedler , whose parents were friends with Otto and Edith Hahn, remembered these years in an award-winning TV documentary:

“The Hahns were with us once, and Frau Hahn said that she knew hundreds of Jews living illegally in Berlin, who were hidden in coal cellars and attics, but that they were slowly starving to death because they were given no ration cards, no meat stamps, no bread stamps . I must have been around 16 then, I think it was early 1943 or late 1942. And while Hahns and my parents were talking about it, also about the danger of air raids that illegally living Jews in Berlin would always stay in the attics had to - because of the air raid shelter - I had the impression that something had to be done and then I made a number of friends. We collected some of our own ration cards, some of which were not owned by others - of course we didn't get to know any of the recipients - instead I brought them to Frau Hahn in Lichterfelde, where the Hahns lived, and she had the distribution mechanism. "

Walther Gerlach , who, despite his rejection of the Nazi system and his distance from the NSDAP, was appointed head of the German uranium project by Hermann Göring and who maintained close contact with Otto and Edith Hahn, later emphasized:

"The cases in which the Hahn couple helped the oppressed and persecuted are countless, openly and even more in secret, regardless of their own endangerment, especially through the use of their foreign relations, which are made through extensive correspondence with friends, colleagues and emigrants in around the world maintained and deepened. "

Otto Hahn always admired and supported the active humanitarian commitment of his wife, which took place in complete secrecy and during this time involved the constant danger of being uncovered by a sudden denunciation , which could have had serious consequences for Edith and himself . Edith, in turn, to give just one example, helped her husband in his intervention with the Gestapo to protect the life of the Jewish chemist Maria von Traubenberg. Hahn managed to get Frau von Traubenberg deported not to Auschwitz but to Theresienstadt , where she was given a room of her own to organize her husband's estate. This decree saved her. (see the article about Otto Hahn ). Edith and her husband were also informed that Hahn's assistant Fritz Strassmann and his wife had given Andrea Wolffenstein a two-month shelter in 1943. For this act, Strassmann was posthumously honored by the Israeli Yad Vashem memorial as Righteous Among the Nations .

When Simon Wiesenthal , who was awarded the Otto Hahn Peace Medal in Berlin in 1991 , learned of Edith Hahn's activities during the Nazi period, he did not spare words of appreciation for her selfless commitment. He called her an "unusually courageous woman" and described her as "an example of courageous action", because in those years "she was in mortal danger practically every day".

Tailfingen (1944-1946)

After Chemical bombed so badly damaged in February and March 1944 Otto Hahn's Kaiser Wilhelm Institute that an unthreatened productive work was almost impossible, he decided the intact remains of the Institute in three disused textile mills after Tailfingen in the Evacuate the Swabian Alb . Edith Hahn followed her husband in June and both moved into two rooms as emergency quarters in the villa of the factory owner Hakenmüller at Panoramastrasse 20, in which they were initially housed until May 1945.

Even under these difficult circumstances, the scientific work at the KWI continued to progress well, and Otto Hahn and his colleagues were able to publish and summarize in a table all substances detected in the institute that are produced during the nuclear fission of uranium. Walther Gerlach writes:

“Every advance was published in scientific newspapers: by the spring of 1945, 25 elements with around 100 isotopes had been determined radiochemically and radiophysically.

The magnitude of the achievement here can only be appreciated if one compares it with the results of the American studies published only a year and a half after the end of the war. The strongest neutron sources and considerable human and financial resources as well as the well-described methods and experiences of Hahn's working groups were available for this. They had led to the detection of not significantly more, namely 36 elements with 170 isotopes. [...]

When the end of the war approached, Otto Hahn persuaded the Mayor of Tailfing to refrain from closing the anti-tank barriers and resisting until the end when the French troops approached: 'Save your town, you will be praised; if you offer senseless resistance, you will be cursed! ' Otto Hahn saved Tailfingen. "

On April 25, 1945, Edith Hahn was interrogated by the American Alsos unit , which had meanwhile arrived in Tailfingen , but her husband was arrested (see Operation Epsilon ) and declared an Allied prisoner for an indefinite period. Professor Max Auwärter, managing director of the nearby company WC Heraeus , writes in a report:

“Immediately after the French soldiers marched in, Americans appeared in Tailfingen on April 25 to pick up Professor Hahn. Despite the lockdown, we managed to see him at the last minute before he had to climb into the open jeep on this freezing cold day. He hoped that the Allies, especially the Americans, would treat him in such a way that he might find ways of maintaining his institute; he hopes to be able to help my laboratory and my colleagues too. These were the last words he addressed to the members of the KWI who said goodbye to him. A few days later, Professor Joliot-Curie appeared , who did everything to avoid endangering the Hahn Institute and its staff. "

Since her husband's internment as part of Operation Epsilon, first in France and Belgium and then from July 3 at the English country estate of Farm Hall near Cambridge, extended to the beginning of January 1946, Edith Hahn, who remained in Tailfingen, was initially at this time on her own, and any correspondence with Otto was forbidden. A special joy was therefore the arrival of her son Hanno, who had been seriously wounded as an officer on the Eastern Front and had become engaged to the nurse Ilse Pletz, who was involved in the amputation of his left arm, at the end of 1944. Both came to Tailfingen at the beginning of May 1945 and initially lived with Edith in the Villa Hakenmüller. For Edith this meant a great spiritual calming down after all the excitement of the last few months. On May 19, Hanno and Ilse got married at the registry office of the Tailfinger town hall. As a result, their living situation improved significantly, as the historian Volker Lässing found out.

“The Tailfinger newspaper publisher Kurt Weidle and his wife Lotte provided Edith Hahn and the newlyweds with a 4-room apartment with a kitchen-living room and a spacious bathroom. A nice apartment, as Josef Mattauch notes in his first letter to Otto Hahn in England. Centrally located, the Hahns lived at Hechingerstraße 6. […] Kurt Weidle's apartment provided the Hahns with an appropriate and friendly home for almost a year. "

Since Edith Hahn, like Magda von Laue, who lived nearby, wife of Max von Laue, who was also interned, had no idea about the whereabouts of their husbands and they were refused further information about their whereabouts, she was able to give Otto the good news about the Do not communicate the wedding. Only after the news blackout for the internees was lifted at the end of August and Otto Hahn was allowed to send the first letter to his wife, Edith was able to contact her husband again and tell him all the news. In response, he wrote in September (he was allowed one letter per month, and all letters were checked and censored):

“My dear Edith, Ilse and Hanno!

I have received your dear letter of August 20th with all previous ones. You can hardly imagine how excited I was waiting for a message from you and how happy I was when I saw that you were all together. There is a lot easier to carry than alone. But now above all my papal blessings for you, my two children! I too believe that the most sensible thing for you was to get married; what should you have been waiting for? Your lovely picture from May 19th is on my table, leaning against a flower jar, for which I cut some beautiful roses from the garden every two days.

You, dear Ilse, are charming about it, Hanno looks a bit miserable. Dear Hanno: Hopefully you are better now that you are out of the hospital and you gain weight again. I very much hope so from you too, dear Edith. [...]

I was also very pleased that the institute still seems to be in progress and that everyone is still there. Greet all, please, I cannot name the names individually. Besides, I hope it won't be long before I get back.

Hopefully you will sleep better now, dear Edith, where you get news from me and where an end of our separation can be expected soon. Max congratulates all three of you on your marriage. - Sincerely - Your Otto "

At the beginning of January 1946, Otto Hahn and his nine colleagues were released from internment in England, and the Allies released him via Alswede (Westphalia) to the British zone in Göttingen . Edith Hahn stayed in Tailfingen, which belonged to the French zone, until the summer. Only on July 21, 1946 did she complete the final formalities and the official de-registration of Otto Hahn and her own registration at the Tailfingen residents' registration office and then moved under difficult conditions to her husband in Göttingen. Almost two months later the publisher Kurt Weidle wrote to Edith:

“We hope that you, dear madam, have now settled in completely. Or do you still miss the peace and quiet of the Tailfinger apartment? Or the bitter shine of our Alb summer? Certainly not the severe cold of winter. [...] The new tenants are also very quiet, you can hardly hear or see anything from them.

Nevertheless, we often miss you, dear madam, your always so kind words, your dear voice. It was just something different from what we are used to here. But this is now your lb. For the benefit of spouses who are entitled to it. A card came from Mr. Hanno today. With enthusiastic words he describes his vacation stay in Frankfurt and the progress of his son. "

Volker Lässing, who meticulously researched Otto and Edith Hahn's Tailfinger time and discovered and evaluated numerous documents believed to be lost, summarizes in the foreword to his historical analysis:

“Otto Hahn, the discoverer of nuclear fission, played a brief but very intensive role in the Tailfinger history and has a lasting effect to this day. Not only his scientific achievements, but also his personal integrity in very difficult times, combined with his always modest personal demeanor, are the reason for Otto Hahn's continued popularity and respect in Tailfingen. [...]

Otto Hahn's sense of responsibility for his institute, for Tailfingen and its citizens prompted him to intervene with the mayor and encourage him to hand over the town without a fight, which has been a district of Albstadt since 1975. Otto Hahn remained loyal to Tailfingen all his life. Even long after the war he paid occasional visits to his private Tailfinger friends. A regular exchange of letters shows Otto Hahn's solidarity.

The Tailfingers dedicated a street on the Lammerberg to their most famous citizen. Since May 2010, a permanent exhibition about Otto Hahn and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Tailfingen has been on view on the first floor of the Tailfinger Academy building of the Reutlingen Chamber of Commerce. "

Göttingen (1946–1968)

Otto and Edith Hahn lived in Göttingen in the apartment of the deceased Privy Councilor Brandi at Herzberger Landstrasse 44, which was intended for them. The house had a beautiful garden in which Edith enjoyed reading books and newspapers in the sun in a deck chair and doing her correspondence. On September 11, 1946, her husband founded the new "Max Planck Society in the British Zone", the successor to the Kaiser Wilhelm Society and the forerunner of the February 1948 after lengthy and exhausting negotiations, especially with General Lucius D. Clay , Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science recognized in all three West German zones . In this too, Otto Hahn was appointed president and unanimously re-elected by the MPG Senate in 1954 for a second term of office until 1960.

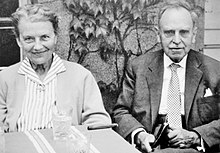

On December 2, 1946, Edith Hahn accompanied her husband on his trip to Stockholm to receive the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, which the Royal Academy had awarded him in 1944 . Both for protection, but also for control, they had been assigned a British officer, a likeable Fraser , with whom they even became friends in the weeks that followed. Looking back, Otto Hahn writes in Mein Leben :

“Lise Meitner, my friend Percy Quensel, Mrs. von Hevesy, an attaché of the Swedish Foreign Ministry and many journalists were waiting for us at our destination. In the noble Savoy we were accommodated excellently and after a long time had dinner with our friends again in a peaceful manner. [...] Many relatives and acquaintances back home received nutritious greetings from Sweden. I remember having the Nordiske Kompagnie put together over 70 parcels and had them sent to Germany. It was an exciting experience for my wife to buy some clothes and shoes, and I was very happy to get a new coat and suit.

But we also enjoyed the atmosphere of this beautiful city, which stood out from the German cities not only because of its integrity; We were impressed by Kungsgatan and many other things, especially since our friends tried very hard for us and tried to erase the war and the post-war period from our memories for a few days. […] The evening of December 12th was marked by a great reception that the King gave for us, the next day I had to give my great lecture in the Academy.

I associate particularly fond memories with my wife's birthday party, which of course couldn't be canceled in Stockholm, and with a visit to Princess Sibylla and Prince Gustav. There the women showed each other pictures of their grandchildren, who were almost the same age. Although both of them admired the beauty of the strange child beyond measure, I am still convinced that each of the grandmothers considered their grandchildren to be the most beautiful child. "

While her husband, as the founder and president of the Max Planck Society, had been working hard since 1948 to secure the existence of the new society nationwide and to consolidate its international reputation, Edith Hahn withdrew more and more into private life. Except for birthday parties and smaller events, she rarely appeared in public with her husband. Since she highly valued the performances of the Göttingen German Theater under the direction of Heinz Hilpert , she was a loyal subscriber and attended the latest productions. She read a lot, biographies, poems, fiction, but above all classics, especially Heinrich Heine and Victor Hugo , and she kept in touch with her friends through extensive correspondence.

When Otto Hahn was seriously injured in October 1951 by the assassination attempt by a mentally disturbed inventor, about which she was deeply shocked, this incident led Edith to renewed psychological problems. Otto Hahn remembered the first half of 1952:

“Then I received a few more invitations that I was initially able to accept. So I gave a lecture in Gothenburg and became a member of the Helsinki Academy. However, a trip to Brazil was no longer an option after my wife suffered a total nervous breakdown in late May. Unfortunately, several shock treatments did not lead to any improvement any more than a stay in a sanatorium, which even had to be broken off prematurely. So there was nothing left but to take my wife to the mental hospital. She stayed there until Christmas without her ailment being completely healed. Since then, she hardly remembers any more recent events, but she has a good memory for things that happened long ago. "

At the beginning of 1953 Otto and Edith Hahn moved into a new apartment on the first floor of a simple residential building at Gervinusstrasse 5, where they lived until their death. The nearby Göttingen city forest offered both of them often used recreation through walks in the good air. Since the late 1940s they have been spending their holidays regularly at the “Albergo Croce Bianca” in Lugano , where Edith could pay homage to her beloved swimming and Otto could go on mountain hikes to Monte Generoso . In March 1954, Edith Hahn took part in a general meeting of the MPG in Wiesbaden for the first time and got to know Federal President Theodor Heuss , Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and the American High Commissioner James B. Conant . At the evening banquet she was the table lady of Adenauer and Conant, with whom she had had a lively conversation in fluent English and about whom she later wrote to her daughter-in-law Ilse Hahn that he was “a really distinguished man, like my Otto”.

Edith Hahn was one of his most important supporters in the 1950s, when her husband, in addition to his office as MPG President, increasingly campaigned for nuclear disarmament, peace and international understanding. And Otto Hahn listened to his wife. The respect he has shown her since 1911 has not been diminished by Edith's occasional visits to mental hospitals. His trust in her remained unbroken. Both exchanged views on cultural and political events, and Otto Hahn valued his wife's clear judgment, which often contributed to his decision-making. When, to give an example, the British philosopher Bertrand Russell asked Otto Hahn in July 1955 to sign the so-called Russell-Einstein Manifesto he had prepared, Hahn wrote Russell that he had to accept this appeal because of "his one-sided left tendency" refuse to sign. A decision that had matured after a discussion with Edith. During the preparation of the Mainau rally initiated by Hahn and published only a week later on Lake Constance by 18 Nobel Prize winners (see Otto Hahn ), Edith contributed clever arguments to the formulation of the final text version. This Mainau manifesto received worldwide resonance precisely because of its neutral words. Alexander Dées de Sterio, a member of the board of trustees of the 1955 Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting, wrote in his chronicle:

“The last sentences of a passionate appeal to the conscience of the mighty were a warning, the manifesto itself a commitment to world peace of the highest order, at the same time a protest against the abuse of scientific progress. It should have its place in every politician's office and in every school class.

The response to the Manifesto of the Eighteen, Concerned for the Continuity of the World, has been overwhelming. It was translated into all languages, it appeared in the newspapers on all five continents, and it brought the Board of Trustees a flood of congratulations, letters, and even further resolutions. Only those responsible were silent. "

Edith Hahn also played a part in some of her husband's other peace initiatives, such as the Göttingen Declaration in April 1957, or his Viennese appeal against A and H bomb experiments . Otto Hahn has confirmed several times, both privately and officially, that Edith's more elegant writing style has repeatedly prompted him to correct his texts.

During a summer vacation in Garmisch-Partenkirchen in August 1960, Otto and Edith Hahn struck "the worst blow that fate could have in store". Her only son Hanno , 38 years old, a recognized art and architecture historian from the Bibliotheca Hertziana in Rome , suffered a car accident with his wife and assistant Ilse Hahn on August 29th at Mars-la-Tour on a study trip through France . Hanno was dead on the spot, Ilse was brought to a clinic in Briey with two fractures of the cervical spine , but died nine days later on September 7th “after a sick bed that was admirably strong”. This tragic event changed Edith's life. In her grief she withdrew completely into herself and was barely accessible. Monika Scholl-Latour describes this condition:

“From that time on, Edith Hahn only wore black. She often sat in front of her children's pictures and cried. Only Otto Hahn could comfort her. Often it was difficult to get her to bed. She preferred to sit in the armchair. When she woke up in her bed at night, she often began to sing loudly. The neighbors were amazed; Little did they know what was going on in the Nobel Laureate's family. They must have been even more amazed when an uncertain tenor voice suddenly mingled with the ghostly female singing: Otto Hahn tried to calm his wife down in this way.

With this kindly bravery, the old researcher succeeded in giving his wife the feeling of security again. Together with her he declaimed ballads and poems as if it were the most natural thing in the world. Otto Hahn kept bringing his wife flowers. He cared for her touchingly. But he also knew how to hide his own pain. [...]

The unhappiness of this marriage proved even more than the happiness of the first decades how great this love was, which outwardly seemed almost petty-bourgeois. "

In March 1968 Otto Hahn was admitted to a clinic in Göttingen due to an injury, where he died of acute heart failure on July 28th after a four-month stay. Edith was not informed of the death of her "beloved chicken" so as not to stress her even more emotionally. But she probably wouldn't have really noticed this information.

Death (1968)

Edith Hahn spent the last few months in a sanatorium near Göttingen. She fell asleep there on August 14th. Three days later she was buried at the side of her husband in the Göttingen city cemetery. Members of the Hahn / Junghans families, numerous friends from all over Germany and some European countries, as well as several public figures, such as the Presidents of the Max Planck Society and the German Research Foundation , the Lord Mayor of Göttingen , took part in the funeral service and funeral and some official representatives of the city of Frankfurt am Main and the state of Berlin. In Göttinger Tageblatt and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung praised published obituaries in particular Edith Hahn's courageous stand during the Nazi era. A short time later, several larger articles, including the magazines Stern and Jasmin, reported in detail and with numerous photos about her life with Otto Hahn.

“They loved each other for more than half a century. They were married to each other for 55 years. He was a man who always carried a tiny red book with him. In it he could read a single sentence in every language of the world with a small magnifying glass: 'I love you.' And he said, 'I'm happy about every day I've lived with her.'

She was a woman who rarely wore jewelry, but always had a small wristwatch on her left wrist. She wore the dial inside as if she didn't want to measure the time she was with her husband. And she said, 'I don't want to live any longer than my husband.'

Today the two lie in the same cemetery in Göttingen, side by side - he since the end of July 1968, she since mid-August. She could only live without him for 17 days. - It is the Hahn couple: Edith and Otto Hahn. A German couple lies here, apparently as plain and simple as their grave in the Göttingen city cemetery. And yet it was a couple whose shared happiness was just as unusual as their shared tragedy. "

Exhibitions (posthumous)

On the occasion of Edith Hahn's 100th birthday in December 1987, at the suggestion of Hermann Josef Abs, a large memorial exhibition was opened in a Deutsche Bank branch in Munich, with 48 watercolors and portrait drawings from the years 1905 to 1912. The exhibition lasted from November 30th until December 30th and was freely accessible during the bank's normal business hours. She enjoyed general attention and not infrequently individual admiration. The banker Abs, a recognized art connoisseur, was particularly surprised by Edith's works and full of praise for her “unusual talent”. In the Süddeutsche Zeitung , the art critic Karl Ude wrote, among other things:

“The painter, who will have a commemorative exhibition for her 100th birthday in the Deutsche Bank branch, Neuhauser Strasse 6, until December 30, was not lucky enough to be able to make a name for herself as an artist, because the 1887 Edith Junghans, born in Szczecin, gave up painting when she met and married Otto Hahn, who later won the Nobel Prize, in 1912, and this retrospective would hardly have come about now, had it not been for a well-known family friend: 86-year-old Hermann J. Abs, Honorary President of Deutsche Bank, who insisted on attending the vernissage in Munich. [...]

As a painter, Edith Junghans stuck to what she had learned and repeatedly painted jugs, pewter jugs, mugs and clay pots with loving care and extremely appropriate to the material. The play of light, the harmony of colors, is sometimes remarkable. In between, the one or the other bitter face of a peasant woman or, in a more cheerful mood, a flower still life. Some personal souvenirs are on display in showcases: a clock, rings, a theater glass. On the open page of her diary (April 17, 1957) it can be read that 18 atomic researchers, including her husband Otto Hahn, are against the hydrogen bomb. At the time she noted: 'The Federal Republic should not take part! Strauss and Adenauer angry. '"

On August 14, 1998, on the initiative of Dietrich Hahn and with the support of the Culture Department of the City of Szczecin and the German Consulate General in Szczecin, a commemorative exhibition was opened in the Szczecin Palace , the city's cultural center, on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of Edith Junghans' death . After it was reported in the Polish media, especially on local television and in several major newspapers, the number of visitors was estimated at over 25,000 by the end of the month, after just two weeks. An astonishing number, since Szczecin is not a city of millions, but only has 420,000 inhabitants. One of the main reasons for this was the biggest daily newspaper in Szczecin, the Kurier Szczecínski , whose culture editor Bogdan Twardochleb devoted a whole "page three" to Edith's biography and her art and gave his report the proud headline of the local patriotic: "Edith Junghans - szczecinianka!" (German: "Edith Junghans - a woman from Stettin!").

Appreciations

- Edith Hahn died. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . 15th August 1968.

- Herbert Uniewski: "If you die I want to be dead too!" - 17 days after the death of the most famous German Nobel Prize winner, his wife also died in Göttingen. In: STERN . No. 36, 1968.

- Monika Scholl-Latour, Oskar Menke: “A long love journey into the night”. After 55 years of happy marriage, Otto and Edith Hahn died in Göttingen. In: Jasmin. No. 38, 1968.

- Karl Ude : The painter who was married to a Nobel Prize winner. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . (Features), December 1, 1987.

- Brigitte Keller: Edith Junghans - a memorial exhibition. In: db-aktuell. No. 1, 1988.

- Deutsche Bank (ed.): Catalog Edith Junghans (1887–1968). Munich 1987.

- Bogdan Twardochleb: Edith Junghans - szczecinianka. In: Courier Szczecínski. August 14, 1998. See also: Gazeta Wyborcza (Kujon polski), August 17, 1998.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dietrich Hahn (Ed.): Otto Hahn - Life and Work in Texts and Pictures. Foreword by Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker . Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-458-32789-4 , pp. 91-101.

- ↑ Walther Gerlach, Dietrich Hahn: Otto Hahn - A researcher's life of our time . Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-8047-0757-2 , p. 108 f.

- ↑ Jessica Hoffmann: Dahlem memorial sites. Frank & Timme, 2007, p. 161. (online)

- ↑ Registry Office Stettin, City District Stettin, Pomerania Births 1887 No. 3414 December 19, 1887.

- ↑ Otto Hahn: My life. The memories of the great atomic researcher and humanist. R. Piper Verlag, Munich / Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-492-00838-0 , p. 99.

- ↑ Brigitte Keller: Edith Junghans - a memorial exhibition. In: db-aktuell, No. 1, 1988, p. 4.

- ↑ See also: Catalog Edith Junghans (1887–1968), ed. from Deutsche Bank , Munich 1988.

- ^ Dietrich Hahn (Ed.): Otto Hahn life and work in texts and pictures. Suhrkamp-Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-458-32789-4 , p. 91.

- ↑ a b c Monika Scholl-Latour, Oskar Menke: “A long love journey into the night”. After 55 years of happy marriage, Otto and Edith Hahn died in Göttingen. In: Jasmin. No. 38, 1968.

- ↑ Otto Hahn: My life. R. Piper Verlag, Munich / Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-492-00838-0 , p. 99 f.

- ↑ Dietrich Hahn (Ed.): Otto Hahn - Life and Work in Texts and Pictures. Suhrkamp-Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-458-32789-4 , p. 95.

- ↑ Dietrich Hahn (Ed.): Otto Hahn - founder of the atomic age. A biography in pictures and documents. Paul List Verlag, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-471-77841-1 , pp. 116-118.

- ↑ Otto Hahn: My life. R. Piper Verlag, Munich / Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-492-00838-0 , p. 102.

- ↑ Brigitte Keller: Edith Junghans - a memorial exhibition. In: db-aktuell, No. 1, 1988, p. 4).

- ↑ See also: Karl Ude : The painter who was married to a Nobel Prize winner. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung. (Features), December 1, 1987.

- ^ Edith Hahn to Emma Junghans, March 28, 1913. In: Dietrich Hahn (Ed.): Otto Hahn - Life and Work in Texts and Pictures. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-458-32789-4 , p. 100.

- ↑ Otto Hahn: My life . R. Piper Verlag, Munich / Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-492-00838-0 , p. 103.

- ↑ Lise Meitner to Edith Hahn, May 15, 1913. In: Dietrich Hahn (Ed.): Otto Hahn - Life and Work in Texts and Pictures. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-458-32789-4 , p. 102.

- ↑ Otto Hahn: Experiences and Insights . With an introduction by Prof. Karl Erik Zimen. Econ Verlag, Düsseldorf / Vienna 1975, ISBN 3-430-13732-2 , p. 49.

- ↑ (Note: Dr. Otto Knöfler & Co., chemical factory in Plötzensee near Berlin)

- ↑ (Note: Mesothorium was the isotope Radium 228, which Otto Hahn discovered in 1907)

- ↑ Herbert Uniewski: "If you die I want to be dead too." - 17 days after the death of the most famous German Nobel Prize winner, his wife died in Göttingen. In: STERN, No. 36, 1968.

- ↑ See also: Monika Scholl-Latour, Oskar Menke: “A long love journey into the night”. After 55 years of happy marriage, Otto and Edith Hahn died in Göttingen. In: Jasmin. No. 38, 1968.

- ↑ See: Otto and Edith Hahn's guest book, entry from May 5, 1929, with all the signatures of the guests. In: Dietrich Hahn (Ed.): Otto Hahn - Founder of the Atomic Age A biography in pictures and documents. Paul List Verlag, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-471-77841-1 , p. 122.

- ↑ Ernest Rutherford to Otto Hahn, May 9, 1929. In: Dietrich Hahn (Ed.): Otto Hahn - Life and Work in Texts and Pictures. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-458-32789-4 , p. 139.

- ↑ Professor Franck resigns from office - voluntary step of the Göttingen Nobel Prize winner , Vossische Zeitung , April 18, 1933.

- ^ Edith Hahn to Ingrid and James Franck, April 22, 1933. (The Joseph Regenstein Library, University of Chicago). In: Dietrich Hahn (Hrsg.): Otto Hahn - life and work in texts and pictures. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-458-32789-4 , p. 144.

- ↑ Otto Hahn: My life. R. Piper Verlag, Munich / Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-492-00838-0 , p. 145.

- ↑ See also: Otto Hahn: In memory of the Haber commemoration 25 years ago. In: Communications from the Max Planck Society, No. 1, 1960, p. 3.

- ^ Max von Laue to Otto Hahn, March 8, 1959. In: Dietrich Hahn (Ed.): Otto Hahn - Life and Work in Texts and Pictures. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-458-32789-4 , p. 150.

- ↑ Otto Hahn: Experiences and Insights . Econ Verlag, Düsseldorf / Vienna 1975, ISBN 3-430-13732-2 , p. 55.

- ↑ Otto Hahn: My life. R. Piper Verlag, Munich / Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-492-00838-0 , p. 149 f.

- ↑ Otto Hahn: Experiences and Insights. Econ Verlag, Düsseldorf / Vienna 1975, ISBN 3-430-13732-2 , p. 55.

- ↑ Walther Gerlach, Dietrich Hahn: Otto Hahn - A researcher's life of our time. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-8047-0757-2 , pp. 109–112.

- ↑ Edith Hahn to Heiner Hahn, June 14, 1940. In: Dietrich Hahn (Ed.): Otto Hahn - Life and Work in Texts and Pictures. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-458-32789-4 , p. 189.

- ↑ Wolf Jobst Siedler: Oral statement. In: Reich capital private - A mirror of customs. Episode 4. 'The big city as a burrow.' Contemporary witnesses describe the years 1941 to 1945. A film by Horst Königstein . Broadcast on October 25, 1987 on Bavarian television.

- ↑ Walther Gerlach, Dietrich Hahn: Otto Hahn - A researcher's life of our time. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft (WVG), Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-8047-0757-2 , p. 109.

- ↑ Simon Wiesenthal in conversation with Dietrich Hahn, December 17, 1991 in Berlin, on the occasion of the award of the Otto Hahn Peace Medal

- ↑ Walther Gerlach, Dietrich Hahn: Otto Hahn - A researcher's life of our time. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft (WVG), Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-8047-0757-2 , p. 104.

- ^ Max Auwärter: Report on the arrest of Professor Otto Hahn in Tailfingen. Manuscript dated April 26, 1945.

- ↑ Volker Lässing: Nobody gets the devil! - Otto Hahn and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Tailfingen. CM-Verlag, Albstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-939219-00-2 , p. 95 f.

- ^ Otto Hahn to Edith Hahn, September 1945. In: Otto Hahn - Experiences and Insights. Econ Verlag, Düsseldorf-Vienna 1975, ISBN 3-430-13732-2 , p. 131 f.

- ↑ Kurt Weidle to Edith Hahn, September 17, 1946. See: Volker Lässing: Nobody gets the devil! - Otto Hahn and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in Tailfingen. CM-Verlag, Albstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-939219-00-2 , p. 100.

- ↑ Volker Lässing: Nobody gets the devil! - Otto Hahn and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in Tailfingen. CM-Verlag, Albstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-939219-00-2 , p. 15 f.

- ↑ Note: Otto Hahn is wrong here; it is the 'Grand Hotel' in Stockholm, which traditionally houses all Nobel Prize winners. The 'Savoy' is a comparable hotel in London.

- ↑ Note: The alleged "grandchild" of Princess Sibylla is her son, the later King Carl XVI. Gustaf , who, like Edith Hahn's grandson Dietrich Hahn , was born in April 1946.

- ↑ Otto Hahn: My life. R. Piper Verlag, Munich-Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-492-00838-0 , p. 206 ff.

- ↑ Otto Hahn: My life. R. Piper Verlag, Munich-Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-492-00838-0 , p. 225 f.

- ^ Edith Hahn to Ilse Hahn, June 14, 1954 (Dietrich Hahn archive, Thailand).

- ↑ Dietrich Hahn (Ed.): Otto Hahn - Life and Work in Texts and Pictures. Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-458-32789-4 , pp. 261-263.

- ↑ Alexander Dées de Sterio: Nobel brought them together - encounters in Lindau. Verlag Friedr. Stadler, Konstanz 1985, ISBN 3-7977-0135-7 , pp. 36-42. See also: Dietrich Hahn (Hrsg.): Otto Hahn - life and work in texts and pictures. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-458-32789-4 , pp. 261-263.

- ↑ Dietrich Hahn (Ed.): Otto Hahn - founder of the atomic age. A biography in pictures and documents. Paul List Verlag, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-471-77841-1 , pp. 249-251 and 288.

- ↑ Otto Hahn: My life. R. Piper Verlag, Munich-Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-492-00838-0 , p. 238.

- ↑ Karl Ude: The painter who was married to a Nobel Prize winner. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung, December 1, 1987.

- ↑ Bogdan Twardochleb: Edith Junghans - szczecinianka! In: Kurier Szczecínski , August 15, 1998.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Junghans, Edith |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Hahn, Edith (married name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German painter, draftsman and art teacher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 13, 1887 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Szczecin |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 14, 1968 |

| Place of death | Goettingen |